Abstract

Bacterial lipopolysaccharides are considered as chief virulent factor and found to be responsible for numerous clinical manifestations and lethal effects in both animals and humans. The ability of LPS to express acute phase proteins and cytokines leads to pathological effects. The study was designed to optimize biomimetic and biodegradable nanoparticles (NPs) based regimen for detoxification of LPS induced toxicity. The surface of NPs was modified with freshly collected red blood cells (RBCs) membranes and polyethylene glycol. Endotoxins were extracted from LPS using E.coli and Salmonella typhi. Chitosan NPs diameter & zeta potential was 78.8 nm & +28.3 mV, while after coating with RBCs membrane and PEG, the size was 712.4,712 nm and potential as + 40 and + 28.6 mV respectively. Albino rats were given endotoxin insult following NPs treatment. There was significant decrease in pyrexia after treatment with coated nanoparticles (98.7 ± 1.23 °F for LPS E. coli & RBCs coated NPs group while 99.7 ± 0.75 °F for LPS salmonella + RBCs coated NPs group). A significant reduction in WBCs count was noted after treatment with RBCs coated NPs, in both LPS E.coli and LPS Salmonella i.e. 11.7 ± 1.2 count/cmm and 11.3 ± 1.1 in comparison to LPS E. coli and LPS Salmonella treated group (17.5 ± 0.9 and 16.8 ± 2.3 count/cmm respectively in comparison to healthy control (12 ± 0.7 count/cmm). A significant reduction was observed in CAT and SOD concentration, after treatment with LPS E. coli and Salmonella treatments i.e. 21.9 ± 1.6, 21.9 ± 1.81 and 21.6 ± 2, and 21.6 ± 2.07 µg/mg protein respectively in comparison to healthy control i.e. 32.7 ± 1.7 & 32.2 ± 1.3 µg/mg protein. There was significant improvement after administration of RBCs coated NPs as the recorded values were 31.1 ± 1.36 and 31.7 ± 1.43 µg/mg protein for LPS E. coli & LPS salmonella respectively. The same pattern was observed for SOD after treatment with RBCs coated NPs (LPS E. coli 31 ± 0.7 µg/mg protein and LPS salmonella 31.2 ± 0.8 µg/mg protein. The similar pattern was observed for pro-inflammatory cytokines level. Histopathological studies also showed significant decrease in morbidity after treatment. Results were analyzed statistically by ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. It is concluded that RBCs membrane coated NPs have great potential for detoxification of LPS derived endotoxins and thus may reduce the morbidity. However, further studies are required for safety and dose optimization of NPs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lipopolysaccharide is the chief constituent bound to the external film of Gram-Negative bacteria. LPS is a single free molecule, whereas endotoxin is a collection of naturally occurring fragments that remain in contact with cells1. Lipopolysaccharides is responsible for the release of cytokines (pro, anti-inflammatory) in the host body to produce the inflammatory response2. All these events may lead to fetal sepsis and vital organ failures3. Detoxification regimens, offering ways to rinse the body against offending agents, are available like anti-virulence therapy resulting from bacterial infections, biological weapons and venomous injuries. Currently available detoxification regimens like protein toxin venom4 monoclonal antibodies, antisera, molecularly imprinted polymers exert their action via targeting the toxin structure. This necessitates the optimization of customized treatments for treatment of various toxic insults5.

Many pharmacological therapies are used to overcome the adverse clinical events by neutralizing LPS6. Blood purification is an important therapy to decrease the level of endotoxin instead of conventional drug therapies7.

Biomimetic membrane coated nanoparticles are capable of eluding the immune recognition, neutralizing toxins and targeting pathogenic bacteria for combating bacterial infections. Recently, the membranes of blood cells i.e. erythrocytes, macrophages, platelets and neutrophils have all been successfully applied for coating to nanoparticles preparation. Cell membranes have distinct features due to various constituents, like membrane lipids, proteins, and glycans8.

This study is based on optimization of biodegradable chitosan NPs for detoxification of LPS induced toxicity in rat model, keeping in mind the porous nature of chitosan NPs as we also reported earlier9,10. Two series of surface modified NPs were prepared; the surface of one series of NPs was modified with erythrocyte membrane and of other with a synthetic polymer, polyethylene glycol (PEG).

Chitosan is used to adsorb the endotoxins due to the presence of the bisphosphorylated group in the backbone of endotoxins and make them negatively charged11. Cationic ligands like chitosan, polymyxin B and polyethyleneimine are used for endotoxin neutralization due to electrostatic charge difference as endotoxins are negatively charged due to presence of bisphosphorylated group12. Chitosan (CS), a polysaccharide, is derived from chitin through demineralization and deproteinization and has a broad exhibit of clinical and horticultural applications.

CS is the biopolymer that shows a cationic character because of the presence of its amino groups13,14,15. Many strategies are used in order to render NPs bio-friendly, as they are recognized by the body as foreign particles and immune system get activated. For this purpose, coated NPs are developed, and coating must be natural, nonreactive and/or may be inert polymeric material16. To make the safe category of NPs, these are coated with the hydrophilic polymer PEG and make them protected from the immune system, aggregation, and opsonization17.

Cell membrane coated NPs are well-designed for identifying the specific disease sites and tumor cells, which is advantageous in context of targeted delivery systems for drug. Cell membrane coated NPs play an important role since they are self and innate to the defense system, and they are effectively sustained to the specific sites. Several drugs developed by cell membrane coated NPs have been studied and are showing potential in in-vivo models18. Various kinds of cell membranes are used for coating NPs like, WBCs, bacteria, thrombocytes, tumor cells, embryonic stem cells and RBCs etc. Membrane coating is not used just for the drug delivery and sustained drug release but also for detoxification, photothermal therapy, immune modulation and simple photodynamic therapy19. PEG has been extensively merged into nanoparticles for spans to dodge the clearance by the immune system and increase systematic biodistribution. To the best of our knowledge, there is currently no such preparation for endotoxin detoxification is available, the main purpose of this study is to prepare RBC membranes and PEG-coated chitosan nanoparticles for endotoxin detoxification, characterization and to assess the potential of these modified chitosan nanoparticles in endotoxin detoxification.

Methodology

Chemicals

Chitosan was purchased from Sigma Aldrich®, (USA), having shrimp shells as biological source, MW I90000-375000 (CAS number 9012-76-4). Biochemical assay reagents and kits were purchased from Quimica Clinica Aplicada, Spain. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) from Duksan Pure Chemicals, Korea. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), from Sigma Aldrich®, (USA) with (CAS number 67–68-5) & MW 78.13. Sodium Tripolyphosphate (TPP), from Sigma Aldrich®, (USA) with (CAS number 7758-29-4) & MW 367.86. Biochemical parameters were performed using kits of Quimica Clinica Aplicada S.A. Oxidative stress markers from kits of Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing Jiancheng technology Co. While for IL-6 and TNF-α ELISA, ELISA kits of Bioassay Technology Laboratory, Shanghai, China were used.

Preparation and purification of Chitosan nanoparticles

Preparation of Chitosan nanoparticles

Ionic gelation method will be used to prepare chitosan nanoparticles in the presence of Sodium Tripolyphosphate (TPP)20. The required solutions of sodium tripolyphosphate and acetic acid were prepared. Sodium tripolyphosphate solution, 1%, was prepared by dissolving 1 g TPP in 100 mL of distilled water. The mixture was mixed well by continuous agitation on a magnetic stirrer at 120 rpm at room temperature. While the acetic acid solution, 1%, was prepared by dissolving 1 mL of acetic acid in 100 mL of distilled water. Chitosan (20 mg) was dissolved in 5 ml of aqueous acetic acid and stirred for about 2 h at 25 °C until a homogenous solution. Aqueous solution of TPP 5 mL (1%) was added into 10mL chitosan solution under constant stirring at room temperature for 30 min.

Purification of Chitosan nanoparticles

After preparation of NPs, the solution was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm at 30ºC for about 1 h. Pellet of NPs was achieved. The settled pellets were collected while the supernatant was discarded. Later, the pellets were dispersed in distilled water with the help of vortex mixture. The dispersion was then sonicated for another 10 min for complete homogenization.

Surface modification of prepared Chitosan NPs with red blood cells membrane and polyethylene glycol

Surface modification of prepared Chitosan NPs with red blood cells membrane

Extraction of red blood cells (RBCs) membrane

Heparinized blood (1mL) was taken from the heart of rat and equal volume of distilled water was added to it. The hypotonic solution was sonicated for 2–3 min by the Elmasonic sonicator. The supernatant was separated, following addition of 1mL of distilled water and mixture was centrifuged for 3–4 min at 13,000 rpm. This procedure was repeated until a clear RBC pellet was obtained. Homogenous suspension of RBCs membrane was obtained by dissolving the pellet in 1 mL of distilled water. The RBCs, after washing, were extruded through 100-nm porous membranes. The purified RBCs membrane obtained were lyophilized and stored for further use21.

Surface modification of Chitosan NPs with RBCs membrane

The RBCs membrane was used for the surface modification of prepared chitosan nanoparticles. For this purpose, 1mL of prepared chitosan NPs solution was mixed with 100 µL of purified RBC vesicle suspension. The resultant mixture was then stirred at 1200 rpm for few minutes followed by the extrusion step through a 100 nm polycarbonate porous membrane with Avanti Lipid Polar Mini Extruder. After placement of filter membrane in the Teflon socket of the Mini Extruder, assembly was secured and closed carefully. The prepared suspension of chitosan NPs and RBCs membrane suspension was stirred on a vortex mixture for 2–3 min and then loaded in one of the extruder syringes and forced into the other syringe through the extruder membrane present between the two syringes. This forced passing was repeated 15–20 times for complete and thorough coating of RBC membrane on chitosan NPs. The purified RBCs coated chitosan NPs were then stored at 4© for further use21.

Surface modification of Chitosan NPs with polyethylene glycol

The surface of prepared chitosan NPs were also modified by polyethylene glycol (PEG). For this purpose, 5 mg of polyethylene glycol (PEG) was weighed properly and 4mL of organic solvent was added in PEG liquid and stirred on magnetic stirrer at room temperature. Chitosan NPs suspension (5 mL) was added drop wise with the help of micro pipette while continuously stirring for 30 min on 1200 rpm to evaporate the organic solvent22.

Characterization of RBCs membrane and PEG coated Chitosan nanoparticles

The prepared chitosan NPs and surface modified with RBCs membrane coated chitosan NPs and PEG coated chitosan NPs were analyzed for hydrodynamic particle size and zeta potential by using Zeta sizer Nano-ZS90.

LPS extraction from Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi and purification

Isolation of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi was performed on selective media. Escherichia coli was performed on nutrient agar while of Salmonella typhi was performed on salmonella shigella (SS) agar. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi was grown in Luria broth and Bertani broth at 37ºC in a shaker incubator overnight respectively. The cultured media was centrifuged and sedimented bacteria were harvested and collected. LPS was extracted by the phenol-water method. Bacterial suspension was centrifuged for five minutes at 10,000×g. The pellets were washed twice with PBS (pH 7.2, 0.15 M) having calcium chloride and magnesium chloride. The pellets were sonicated on ice for 10 min after being resuspended in 10 ml PBS solution. Solution was then mixed with 90% equal volume of hot phenol (65–70ºC) and shaked at a temperature of 65–70ºC for 15 min.

On ice suspension was then cooled and transferred to a 15mL polypropylene tube, centrifuged at 8500×g for fifteen min. The supernatant was then transferred to a tube and phenol phases re-extracted by 300 µL of distilled water. After addition of sodium acetate and ethanol to the extract, sample was stored at −20ºC overnight to precipitate LPS. The suspension was then again centrifuged at 2000×g at 4ºC for 10 min. Pellets were resuspended in 1mL of distilled water after dialysis through a membrane23.

Endotoxin insult to experimental animals and detoxification effects of nanoparticles

Animals housing, feeding and grouping

The in vivo experiments were conducted on albino rats using them as experimental animals. The rats were procured from University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Lahore. Thirty-five rats of both sex with body weight of 250–300 g were kept in animal house of University of Agriculture, Faisalabad. These animals were provided with adequate food and well-suited environment according to standard conditions. All the in-vivo experiments were conducted after taking permission from the Institutional Biosafety and Bioethical committee of University of Agriculture, Faisalabad (letter vide no.3666/ORIC).

All animals were sacrificed at end of experiment. For this purpose, the rats were initially anesthetized. The procedure began with the administration of anesthesia using a combination of ketamine 50–100 mg/kg) and xylazine (5–10 mg/kg), with the dosage adjusted based on the rat’s weight. Anesthetic depth was confirmed by checking the absence of the pedal reflex and ensuring stable breathing, while body temperature was maintained with a heating pad, and corneal drying was prevented with ophthalmic ointment. The anesthetized rat was positioned supine on a sterile surgical table, the abdominal area disinfected with 70% ethanol or povidone-iodine, and sterile drapes were used to isolate the surgical field. Efforts to alleviate suffering for rats during trials include minimizing pain through appropriate anesthesia and analgesia, ensuring proper handling to reduce stress, and providing clean, comfortable housing. Finally, the rats were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Adhering to ethical guidelines, using humane endpoints, and monitoring their health regularly further ensures their well-being24.

Experimental design and treatment allocation

Seven groups were made by dividing 35 rats (n = 5) in each group. Animals grouping with treatment administration, dose and frequency has been discussed followings: First control group rats were administered with normal saline and routine diet. The 2nd and 3rd groups received LPS from E. coli (150uL/Kg) and LPS from Salmonella (150uL/Kg) respectively. The rest of the groups received treatment with different modified and coated forms of chitosan NPs. The 4th and 5th groups were administered with LPS E. coli + RBC coated NPs (20ug/Kg) and LPS Salmonella + RBC coated NPs (20ug/Kg) respectively. While 6th and 7th groups were administered with LPS E. coli + PEG coated NPs (20ug/Kg) and LPS salmonella + PEG coated NPs (20ug/Kg). The rats were observed for a period of seven days post administration. All treatments were administered via subcutaneous route (SC).

LPS insult to animals and treatment administration

LPS from E. coli and Salmonella was injected subcutaneously to rats. Rats were observed for 72 h regarding any visible lesions. While, treatments were administered on 3rd day to rats of groups 4–7. Animals were observed for 07 days for visible lesion, pyrogenicity and then sacrificed for further investigations.

Determination of pyrogenicity

Before and after the treatments administration, pyrogen test was performed by rectal thermometry on every other day during the experimental period. The digital thermometer was inserted in the rectum of the rats and the temperature was noted until a stable reading on the thermometer appeared indicating the body temperature of the respective rats. This same procedure was repeated on all rats of all groups.

Blood sampling and serum separation

At the end of experiment, animals were scarified and blood samples were collected immediately in gel and clot activators as well as EDTA vacutainer tubes. The gel and clot activator tubes were then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min and then the serum was collected carefully by the help of micropipette in Eppendorf tubes. The tubes were stored in the freezer at −20ºC for further analysis.

Study of hematological parameters

The blood samples in EDTA vacutainer tube were collected and mix gently to prevent blood from clotting. On the freshly collected blood samples, the hematological parameters such as Red Blood Cell (RBCs) count, White Blood Cell (WBCs) count, platelets count along with the determination of erythrocyte indices i.e. hemoglobin, mean cell volume (MCV), Mean Cell Hemoglobin (MCH) and Mean Cell Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC) were investigated. These investigations were performed using CBC analyzer Medonic, Germany.

Determination of biochemical markers

The collected serum samples of experimental animals were used for investigation of various biochemical markers. Biochemical analysis including liver function test (LFTs) such as aspartate amino transferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were determined. Similarly, kidney function test including creatinine and urea level were determined with commercially available biochemical kits Quimica Clinica Aplicada S.A according to instructions of manufacturer.

Determination of oxidative stress markers

Oxidative stress markers, i.e. catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were determined in serum samples of normal control, LPS administered groups and treatment groups. All these markers were determined according to manufacturer instructions using commercially available kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing Jiancheng technology Co. Ltd).

Determination of Pro-inflammatory cytokines

The concentration of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) was determined in serum samples using ELISA kits of Bioassay Technology Laboratory, Shanghai, China. These kits use enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) principle to determine cytokine level in serum samples. Both of these values were determined according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Determination of mutagenic metabolites in serum by Ames bacterial reverse-mutation test

In order to determine the safety of NPs, the serum samples of NPs treatment groups were explored for presence and/or production of mutagenic metabolites. For the purpose, Ames bacterial reverse mutation test was employed. Reagent mixture comprised of Davis-Mingioli salt, bromocresol purple, L-Histidine, D-glucose and D-Biotin. These were mixed aseptically as previously established protocol25. Two mutant strains Salmonella typhimurium TA98 and TA100 were used. The mixed contents (200 µl) were dispensed into each well of 96-well microtiter plate. The plates were incubated for 4 days at 37 °C after placing them in air tight plastic bag in order to avoid evaporation. The standard, background and test plate were visually scored. All the purple wells were scored negative while yellow or turbid wells were considered as positive. The serum samples will be considered to contain any mutagenic metabolite if number of positive wells becomes twice the number of positive wells in background plate25.

Mutagenic index was calculated by using the following formula as in our previous studies26,27

Histological analysis

In order to determine the effect of LPS and NPs treatments, histological studies were conducted. The liver and kidney of all sacrificed animals were removed and kept in 10% formalin solution. The histological analysis was done after blindly assessing the tissue sections to different groups.

Statistical analysis

All the results were expressed in terms of average values ± SEM. All the results were analyzed statistically by Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s Multiple Range (DMR) using Graph Pad prism software version 06.

Results

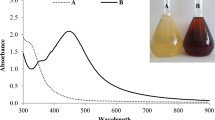

Characterization of nanoparticles

The results of zeta size, potential and polydispersity index of chitosan NPs, RBCs membrane coated NPs and PEG coated NPs have been shown in Table 1. The average hydrodynamic size of chitosan NPs was found to be 78.8 nm. After coating with RBCs membrane and PEG, the size of NPs increased to 712.4 and 712 nm respectively. The Zeta potential of chitosan nanoparticle was + 28.3 mV as shown in Table 1. While the zeta potential of RBC membrane coated NPs was found to be + 40 and + 28.6 mV for PEG coated NPs. The polydispersity index for chitosan NPs, RBCs and PEG coated NPs was found to be 0.40, 0.44 and 0.41 respectively.

Pyrogenicity results

The average body temperature significantly increased in LPS E. coli and Salmonella treatment groups (i.e. 102.2 ± 1.25 °F and 102.5 ± 1.33 °F respectively) in comparison to healthy rats (98.67 ± 0.59 °F) as shown in Fig. 2. Treatment administration, however, significantly reduced the average body temperature throughout the experiment period. The recorder temperatures for treatment groups were; (98.7 ± 1.23 °F) for LPS E. coli + RBCs coated NPs group, (99.7 ± 0.75 °F) for LPS salmonella + RBCs coated NPs group, (99.7 ± 1.4 °F) for LPS E. coli + PEG coated NPs group and (100.3 ± 1.26 °F) for LPS Salmonella + PEG coated NPs group as shown in Fig. 1.

Hematological examination

The results of hematological studies have been shown in Fig. 2. The values of RBCs significantly decreased in both LPS E. coli and Salmonella groups i.e. (5.4 ± 0.3 mil/ccm) and (5.3 ± 0.5 mil/cmm) respectively in comparison to healthy control (6.13 ± 0.3 mil/cmm). While the treatment administration improved RBCs count as in LPS E. coli + RBCs coated NPs group (5.8 ± 0.5 mil/cmm), LPS salmonella + RBCs coated NPs group (5.6 ± 0.3 mil/cmm), LPS E. coli + PEG coated NPs group (5.36 ± 0.1 mil/cmm), LPS salmonella + PEG coated NPs group (5.22 ± 0.08) as shown in Fig. 2a.

While WBCs count significantly increased in LPS E. coli and LPS Salmonella treated group (17.5 ± 0.9 × 103 and 16.8 ± 2.3 × 103 respectively in comparison to healthy control (12 ± 0.7 × 103). After treatment with RBCs coated NPs, WBCs count was reduced in both LPS E.coli and LPS Salmonella i.e. 11.7 ± 1.2 × 103 and 11.3 ± 1.1 × 103. The treatment with PEG coated NPs also reduced WBCs count but not as significant as RBCs coated treatment. The recorded values were 15.4 ± 0.4 × 103 for LPS E. coli + PEG coated NPs while 15.2 ± 0.8 × 103 for LPS salmonella + PEG coated NPs as shown in Fig. 2(b).

A significant reduction was recorded in erythrocyte indices i.e. hemoglobin, MCV, MCH, hematocrit (HCT) and MCHC(%) following the LPS administration. Treatment administration of RBC coated NPs resulted in significant improvement in these parameters. The results of various erythrocyte indices have been shown in Fig. 2(c-e).

Determination of liver and kidney function markers

The results of liver & kidney function tests have been shown in Fig. 3. A significant reduction was observed in ALT level after treatment with LPS E. coli and Salmonella treatments i.e. 60.46 ± 1.75 IU/L and 59.9 ± 2.09 IU/L respectively with reference to healthy control group (30.01 ± 1.35 IU/L) as shown in Fig. 3a. A significant improvement was observed after administration of RBCs coated NPs as the recorded values were 41.7 ± 1.6 IU/L and 45.6 ± 1.43 IU/L for LPS E. coli + RBCs coated NPs and LPS salmonella + RBCs coated NPs respectively. Administration of PEG coating also improved ALT concentration but not as significantly as previous treatment. The values of PEG coated NPs to LPS E. coli and LPS Salmonella were 50.2 ± 2.86 IU/L and 53.8 ± 1.30 IU/L. The similar pattern was observed for AST (Fig. 3b).

In case of kidney function tests, a significant increase was observed in blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine level after treatment with LPS E. coli and Salmonella treatments i.e. (18.96 ± 0.65 mg/dL & 18.54 ± 0.36 mg/dL for BUN) and (1.12 ± 0.83 mg/dL & 1.11 ± 0.14 mg/dL for creatinine) respectively with reference to healthy control group (14.79 ± 0.14 mg/dL and 0.84 ± 0.016 mg/dL) as shown in Fig. 3c and d. A significant improvement was observed after administration of RBCs coated NPs as the recorded values for BUN were 15.34 ± 0.41 mg/dL and 16.14 ± 0.29 mg/dL for LPS E. coli + RBCs coated NPs and LPS salmonella + RBCs coated NPs respectively. Administration of PEG coating also lowered BUN value but not as significantly as previous treatment. The values of PEG coated NPs to LPS E. coli and LPS Salmonella were 16.7 ± 0.49 mg/dL and 17.14 ± 0.42 mg/dL. The similar pattern was observed for creatinine and values are shown in Fig. 3d.

Determination of oxidative stress markers

The results of antioxidant enzymes have been shown in Fig. 4(a & b). A significant reduction was observed in CAT concentration after treatment with LPS E. coli and Salmonella treatments i.e. 21.9 ± 1.6 µg/mg protein and 21.9 ± 1.81 µg/mg protein respectively with reference to healthy control group (32.7 ± 1.7 µg/mg protein) as shown in Fig. 4a. A significant improvement was observed after administration of RBCs coated NPs as the recorded values were 31.1 ± 1.36 µg/mg protein and 31.7 ± 1.43 µg/mg protein for LPS E. coli + RBCs coated NPs and LPS salmonella + RBCs coated NPs respectively. Administration of PEG coating also improved CAT concentration but not as significantly as previous treatment. The values of PEG coated NPs to LPS E. coli and LPS Salmonella were 29.8 ± 0.84 µg/mg protein and 29.6 ± 0.9 µg/mg protein.

The values of SOD significantly decreased in LPS E. coli treated group (21.6 ± 2 µg/mg protein), LPS salmonella treated group (21.6 ± 2.07 µg/mg protein) in comparison to healthy control (32.2 ± 1.3 µg/mg protein) as shown in Fig. 4 (b). LPS E. coli + RBCs coated NPs administration significantly improved the SOD level in both LPS E. coli (31 ± 0.7 µg/mg protein) and LPS salmonella group (31.2 ± 0.8 µg/mg protein). Treatment of PEG coated NPs also improved SOD level as the recorded values were 28 ± 1.18 µg/mg protein and 28.6 ± 0.8 µg/mg protein for LPS E. coli and LPS Salmonella.

Determination of pro-inflammatory cytokines

The values of TNF-α significantly increased in LPS E. coli and LPS Salmonella treated groups i.e. 3.14 ± 0.3 and 3.06 ± 0.3 pg/mL respectively in comparison to healthy control (1.04 ± 0.24 pg/mL). The treatment administration significantly reduced the values as observed in LPS E. coli + RBCs coated NPs group (1.2 ± 0.27 pg/mL), LPS salmonella + RBCs coated NPs group (1.19 ± 0.3 pg/mL), LPS E. coli + PEG coated NPs group (1.4 ± 0.4 pg/mL), LPS salmonella + PEG coated NPs group (1.34 ± 0.39 pg/mL) as shown in Fig. 5 (a).

The values of IL-6 also increased significantly in LPS E. coli and LPS salmonella treated group 2.72 ± 0.23 and 2.7 ± 0.3 pg/mL respectively. The treatment administration reduced these levels as in LPS E. coli + RBCs coated NPs group (1.9 ± 0.31 pg/mL), LPS salmonella + RBCs coated NPs group (1.84 ± 0.15 pg/mL), LPS E. coli + PEG coated NPs group (2.31 ± 0.2 pg/mL), LPS salmonella + PEG coated NPs group (2.24 ± 0.23 pg/mL) as shown in Fig. 5(b).

Determination of mutagenic metabolites in serum by Ames test

The results of mutagenicity index have been shown in Fig. 6. The mutagenic index of equal or greater than 2 was considered as mutagenic. The mutagenic index of all NPs treatment groups was below 2 which indicated that no mutagenic metabolite was present in serum samples following the administration of chitosan NPs as well as RBCs and PEG coated NPs.

Histopathological examination

The histopathological analysis of liver and kidney was made and results have been shown in Fig. 7. Following LPS administration, there was necrosis, edema, cellular degeneration inflammatory changes as well as congestion of blood in both liver and kidney. Glomerulus and tubular damage were also seen in the kidneys of LPS treated animals (Fig. 7b and c). Administration of treatment by RBCs membrane and PEG coated NPs resulted in significant improvement of these destructive changes as shown in Fig. 7d and e.

Photomicrographs of histopathological analysis of kidney and liver in LPS versus treatment groups at scale bar of 100 μm (a) Kidney and liver of healthy group (b) Kidney and liver of LPS E. coli treated group (c) Kidney and liver of LPS Salmonella treated animals (d) Kidney and liver of LPS E.coli + RBCs coated chitosan NPs (e) Kidney and liver of LPS Salmonella + RBCs coated chitosan NPs (f) Kidney and liver of LPS E.coli + PEG coated chitosan NPs (g) Kidney and liver of LPS Salmonella + PEG coated chitosan NPs.

Discussion

Nanoparticle-based formulations have several advantages over their free-drug counterparts, including improved pharmacokinetics, reduced systemic exposure, side effects and better patient compliance. An important feature is a long systemic circulation half-life, which requires the nanoparticles to evade capture by the macrophages of the mononuclear phagocyte system28. The NPs, in the biological system, are known as foreign substances, which are then easily removed by passive immune clearance29. To overcome these challenges, surface modification with polyethylene glycol (PEG), also called as PEGylation, has been proposed to enhance performance of NPs owing to its stealth effect, which effectually safeguards the negative effects of the cationic domains on NPs surface, thus prevent adsorption of non-specific proteins and enlightening NPs biocompatibility and protease stability30. To overcome the challenges of NPs, scientists have been working biomimetic nanoparticles. Cell membrane has numerous vital functions such as active targeting, biocompatibility, and self-recognition. Another very important function is “decoy”, similar to sponges, with the ability of “soaking up” detrimental pathogens, toxins, or pro-inflammatory cytokines for neutralization31. In NPs, coated with the cell membrane, the external plasma membrane covering receives the above functions. The NPs interior acts as a stabilizing agent for the external membrane shell. Thus, membrane coated NPs have the functions of both the NPs as well as cell membranes, including biocompatibility, toxins neutralizing and/or inflammatory cytokines, which allows NPs to fight against muti-targets in a single treatment32.

Modified nanoparticles have a great ability to absorb endotoxin from the blood. In this study, we modified the surface of chitosan NPs with RBC membrane and PEG in order to evaluate its effectiveness against LPS derived from G-VE bacteria. Modified chitosan nanoparticles are considered biodegradable and biocompatible in nature that can absorb LPS on its surface thereby reducing its toxic effect and hence decreasing relevant toxic effects. The RBCs coated NPs are specifically used for the detoxification of endotoxins produced by the staphylococcus5.

The size of our prepared chitosan nanoparticles is 78.8 nm. Chitosan NPs size is in accordance with our previous studies33. Even after modifications with RBCs membrane and PEG, the size increased but was found to be within nano-sized range. Zeta size is a very important parameter for the characterization of nanoparticles hence the NPs fall within size range of 10–1000 nm diameter34. Zeta potential of chitosan NPs was + 28.3 mV which corresponds to cationic nature of chitosan as we already reported in our previous studies9,10,14. The surface modified NPs with RBCs and PEG coating exhibited zeta potential of + 40 and + 28.6 mV respectively.

LPS, being the main component of gram-negative bacteria, induce inflammatory reactions after binding to CD14 and LPS binding proteins35,36. Inflammatory response is initiated by enhanced cytokine production by activating TLR4 pathway. Inflammatory response activation is useful for better clearance of bacteria and LPS. Abundance of circulatory LPS, however, renders the inflammatory response harmful and may lead to tissue dysfunction, multi organ failure and ultimately death36,37. Inflammation and infection result in numerous metabolic changes like enhanced thermogenesis, negative energy balance and anorexia. LPS triggers behavioral responses like malaise and fever as host-defense mechanism refereed by cytokines38. Current study was designed to investigate anti-inflammatory activity of RBCs and PEG chitosan nano particles. Prepared nanoparticles showed higher activity in reducing inflammation in comparison to LPS administered groups. Level of IL-6 and TNF-alpha also reduced which resulted in reduction of inflammation induced pyrexia. At the same time, toxic effects on liver and kidney, as evident from LFTs and kidney function tests, were also found to be reduced due to associated inflammatory cytokines. The membrane coated NPs have potential to neutralize and bind broad spectrum of inflammatory agents and toxins and are accomplished of non-specifically adsorbing a diversity of these substances39,40.

Ames test is generally employed method that use the bacteria to identify the given chemical whether it causes mutation in the DNA of the test animal. Moreover, it also called biological assay that asses the mutagenic potential of given chemicals. In order to assess the production of any mutagenic metabolites following the administration of NPs treatment, ames assay was performed on treatment groups. Any sample with mutagenic index value of equal or greater than 2 is considered as mutagenic as we reported in our previous studies26,27. The serum samples of all treatment groups showed mutagenic index less than 2 and hence it was confirmed that NPs administration didn’t produce any mutagenic metabolites in experimental animals.

LPS treated groups showed marked inflammation, erythrocyte congestion and sinusoidal dilatation in liver while degeneration of glomerulus in kidney tissues in comparison to normal control group as shown in Fig. 7. Administration of RBCs membrane and PEG coated NPs significantly reduced the inflammation and cellular degeneration (Fig. 7) which can also be corelated with decreased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines as well as improvement in the level of liver and kidney function tests in treatment groups.

Conclusion

Based upon the findings of this study, we conclude that significant detoxification effect was observed in rats treated with RBCs membrane coated NPs by restoring altered inflammatory, oxidative stress and biochemical parameters to normal levels. However, further studies are required for dose optimization and safety of modified nanoparticles. We believe that this study will be helpful in understanding the mechanisms behind LPS induced insult and may help in detoxification of LPS induced effects.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Jackie, J., Lau, W. K., Feng, H. T. & Li, S. F. Y. Detection of endotoxins: from inferring the responses of biological hosts to the direct chemical analysis of lipopolysaccharides. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 49, 126–137 (2019).

Ankawi, G. et al. Extracorporeal techniques for the treatment of critically ill patients with sepsis beyond conventional blood purification therapy: the promises and the pitfalls. Crit. Care. 22, 1–16 (2018).

Klein, D. J. et al. Daily variation in endotoxin levels is associated with increased organ failure in critically ill patients. Shock 28, 524–529 (2007).

Akhtar, B., Muhammad, F., Sharif, A. & Anwar, M. I. Mechanistic insights of snake venom disintegrins in cancer treatment. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 899, 174022 (2021).

Hu, C. M. J., Fang, R. H., Copp, J., Luk, B. T. & Zhang, L. A biomimetic nanosponge that absorbs pore-forming toxins. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 336–340 (2013).

Opal, S. M. et al. Effect of eritoran, an antagonist of MD2-TLR4, on mortality in patients with severe sepsis: the ACCESS randomized trial. Jama 309, 1154–1162 (2013).

Vorobii, M. et al. Antifouling microparticles to scavenge lipopolysaccharide from human blood plasma. Biomacromolecules 20, 959–968 (2019).

Song, Y. et al. Recent advances of cell membrane-coated nanoparticles for therapy of bacterial infection. Front. Microbiol. 14, 1083007 (2023).

Akhtar, B., Muhammad, F., Aslam, B., Saleemi, M. K. & Sharif, A. Biodegradable nanoparticle based transdermal patches for gentamicin delivery: formulation, characterization and pharmacokinetics in rabbits. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 57, 101680 (2020).

Akhtar, B., Muhammad, F., Aslam, B., Saleemi, M. K. & Sharif, A. Pharmacokinetic profile of Chitosan modified Poly lactic co-glycolic acid biodegradable nanoparticles following oral delivery of gentamicin in rabbits. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 164, 1493–1500 (2020).

Konwar, A., Chowdhury, D. & Dan, A. Chitosan based in situ and ex situ magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for rapid endotoxin removal from protein solutions. Mater. Chem. Front. 3, 716–725 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Anticoagulant chitosan-kappa-carrageenan composite hydrogel sorbent for simultaneous endotoxin and bacteria cleansing in septic blood. Carbohydr. Polym. 243, 116470 (2020).

Cross, T. W. L., Kasahara, K. & Rey, F. E. Sexual dimorphism of cardiometabolic dysfunction: gut Microbiome in the play? Mol. Metabolism. 15, 70–81 (2018).

Anwar, M., Muhammad, F., Akhtar, B. & Saleemi, M. K. Nephroprotective effects of Curcumin loaded Chitosan nanoparticles in Cypermethrin induced renal toxicity in rabbits. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 14771–14779 (2020).

Akhtar, B., Muhammad, F., Aslam, B. & Saleemi, M. K. Toxicity studies of oral and transdermal formulations of gentamicin loaded PLGA nanoparticles in animal model. Pak Vet J. (2020). http://www.pvj.com.pk/abstract/in_press/19-405. htm accessed 28 March 2020). Google Scholar (2019).

Suk, J. S., Xu, Q., Kim, N., Hanes, J. & Ensign, L. M. PEGylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle-based drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 99, 28–51 (2016).

Dash, P., Piras, A. M. & Dash, M. Cell membrane coated nanocarriers-an efficient biomimetic platform for targeted therapy. J. Controlled Release. 327, 546–570 (2020).

Huang, Y. et al. Bioinspired tumor-homing nanosystem for precise cancer therapy via reprogramming of tumor-associated macrophages. NPG Asia Mater. 10, 1002–1015 (2018).

Liu, Y., Luo, J., Chen, X., Liu, W. & Chen, T. Cell membrane coating technology: a promising strategy for biomedical applications. Nano-Micro Lett. 11, 1–46 (2019).

Qi, L., Xu, Z., Jiang, X., Hu, C. & Zou, X. Preparation and antibacterial activity of Chitosan nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Res. 339, 2693–2700 (2004).

Hu, C. M. J. et al. Erythrocyte membrane-camouflaged polymeric nanoparticles as a biomimetic delivery platform. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 10980–10985 (2011).

Zhao, P. et al. Paclitaxel loaded folic acid targeted nanoparticles of mixed lipid-shell and polymer-core: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 81, 248–256 (2012).

Rezania, S. et al. Extraction, purification and characterization of lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi. Avicenna J. Med. Biotechnol. 3, 3 (2011).

Shakir, N. et al. Pirarubicin loaded biodegradable nanoparticles downregulate IL-6, COX-II and TNF-α along with oxidative stress markers in comparison to conventional pirarubicin in healthy albino rats. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 84, 104498 (2023).

Iqbal, M. et al. Mutagenicity and cytotoxicity evaluation of photo-catalytically treated petroleum refinery wastewater using an array of bioassays. Chemosphere 168, 590–598 (2017).

Sharif, A. et al. Pharmaceutical wastewater being composite mixture of environmental pollutants May be associated with mutagenicity and genotoxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23, 2813–2820 (2016).

Sharif, A. et al. Genotoxic and cytotoxic potential of whole plant extracts of Kalanchoe laciniata by Ames and MTT assay. EXCLI J. 16, 593 (2017).

Allémann, E., Leroux, J. C., Gurny, R. & Doelker, E. In vitro extended-release properties of drug-loaded Poly (DL-lactic acid) nanoparticles produced by a salting-out procedure. Pharm. Res. 10, 1732–1737 (1993).

Wang, X. et al. Cell-membrane-coated nanoparticles for the fight against pathogenic bacteria, toxins, and inflammatory cytokines associated with sepsis. Theranostics 13, 3224 (2023).

Tan, P. et al. Designing self-assembling chimeric peptide nanoparticles with high stability for combating piglet bacterial infections. Adv. Sci. 9, 2105955 (2022).

Rampado, R., Caliceti, P. & Agostini, M. Latest advances in biomimetic cell membrane-coated and membrane-derived nanovectors for biomedical applications. Nanomaterials 12, 1543 (2022).

Li, R., He, Y., Zhang, S., Qin, J. & Wang, J. Cell membrane-based nanoparticles: a new biomimetic platform for tumor diagnosis and treatment. Acta Pharm. Sinica B. 8, 14–22 (2018).

Saleem, M. U. et al. Methotrexate-loaded biodegradable nanoparticles exert anti-arthritic effect by downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines in freund’s complete adjuvant-induced arthritic rats. Inflammopharmacology 30, 1079-1091 (2022).

Van Den Bemt, B. J., Zwikker, H. E. & Van Den Ende, C. H. Medication adherence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a critical appraisal of the existing literature. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 8, 337–351 (2012).

Ngkelo, A., Meja, K., Yeadon, M., Adcock, I. & Kirkham, P. A. LPS induced inflammatory responses in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells is mediated through NOX4 and Giα dependent PI-3kinase signalling. J. Inflamm. 9, 1–7 (2012).

Borzęcka, K., Płóciennikowska, A., Björkelund, H., Sobota, A. & Kwiatkowska, K. CD14 mediates binding of high doses of LPS but is dispensable for TNF-α production. Mediators of Inflammation (2013). (2013).

Tucureanu, M. M. et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in monocytes/macrophages is blocked by liposomal delivery of Gi-protein inhibitor. Int. J. Nanomed. 13, 63 (2018).

Sachot, C., Poole, S. & Luheshi, G. N. Circulating leptin mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced anorexia and fever in rats. J. Physiol. 561, 263–272 (2004).

Wang, S. et al. Cellular nanosponges for biological neutralization. Adv. Mater. 34, 2107719 (2022).

Parodi, A. et al. Bio-inspired engineering of cell-and virus-like nanoparticles for drug delivery. Biomaterials 147, 155–168 (2017).

Funding

The study has not received any funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: T. A, B.A, A.S, and F. (A) Investigation, formal analysis by T. A, B.A, A.S, F. A, S.A and S.A.F writing-original draft preparation and editing: T. A, B.A, A.S, F. A, S.A, S.A.F and T. M. Resources; T. A, B.A, A.S, Critical review: B.S and T.M; Supervision: (B) A. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the draft manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All the in-vivo experiments on animals were conducted after taking permission from the Institutional Biosafety and Bioethical committee of University of Agriculture, Faisalabad (letter vide no.3666/ORIC). The experiments were conducted in accordance with the NC3Rs ARRIVE Guidelines, adhere to ethical guidelines of The Basel Declaration, the International Council for Laboratory Animal Science (ICLAS) ethical guide lines, and Directive 2010/63/EU. All procedures followed were in accordance with the standards outlined in the eighth edition of “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (grants.nih.gov/grants/olaw/guide-for-the-care-and use-of-laboratory-animals_prepub.pdf published by the National Academy of Sciences, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aslam, T., Akhtar, B., Sharif, A. et al. Erythrocyte membrane coated biodegradable nanoparticles detoxify LPS-induced toxicity by producing non-mutagenic metabolites and downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress markers. Sci Rep 15, 33634 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07196-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07196-y