Abstract

This study investigates the use of hydrochars derived from sweet potato residue (Ipomoea batatas), Indian mallow (Abutilon theophrasti Medicus), and Nan bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis) for diesel adsorption in oily wastewater treatment. Hydrochars were prepared via hydrothermal carbonization, and their adsorption kinetics and thermodynamics were evaluated. The optimal adsorption conditions for sweet potato residue hydrochar (SPRH) were: 1.8 g·L− 1 dosage, 479 mg·L− 1 diesel concentration, pH 4-, and 120-min adsorption time, with a capacity of 165.52 mg·g− 1. Kinetic studies revealed that adsorption followed a pseudo-second-order model, and the isotherm fitted the Langmuir model. For Indian mallow hydrochar (IMH), optimal conditions were: 1.4 g·L− 1 dosage, 398 mg·L− 1 diesel concentration, pH 3.18, and 100 min, achieving 157.41 mg·g− 1 capacity. IMH adsorption also followed the pseudo-second-order model, driven by chemical adsorption. Nan bamboo hydrochar (NBH) showed optimal conditions at 1.8 g·L− 1 dosage, 502 mg·L− 1 diesel concentration, pH 3.92, and 120 min, with a diesel adsorption capacity of 193.75 mg·g− 1. Chemical modification of NBH with KMnO4, H2O2, H3PO4, and HNO3 improved adsorption by 12.38–21.25%. After four adsorption-desorption cycles, modified NBH retained 63.24% of its initial capacity, indicating good stability and regeneration potential. These findings suggest that modified NBH offers a cost-effective, efficient solution for oily wastewater treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oil is a key energy resource for global industrial development; however, its extraction, processing, and use generate oily wastewater, which poses a significant environmental threat1. As industrial development continues, particularly in heavy industry, large-scale industry, and emerging sectors, oily wastewater discharge is on the rise. Global oily wastewater discharge has reached approximately 1.3 × 109 m³, with this number continuing to increase annually2. Offshore oil platforms and large oil fields are the primary sources of wastewater in the oil industry3. These wastewaters contain harmful substances, including organic solvents and surfactants, which not only pollute the environment but also threaten human, animal, plant, and microbial health4. The presence of these pollutants deteriorates water quality, harms aquatic life, disrupts ecological balance, and poses risks to human health via the food chain. Oily wastewater primarily originates from oil fields, refineries, and petrochemical industries, exhibiting complex and diverse characteristics. As industry continues to develop, the discharge of oily wastewater is increasing, leading to significant impacts on the environment and ecosystems5. Effective environmental protection measures are essential to address this challenge.

Common wastewater treatment methods include coagulation/flocculation6, biological7, filtration, electrochemical8, and adsorption processes9. Each method has specific applications. Coagulation/flocculation processes use chemical agents to aggregate and settle oil droplets, making them effective for removing emulsified and suspended oils10. Biological processes rely on microorganisms to degrade oily compounds, particularly effective for treating wastewater with dissolved oils11,12. Filtration processes physically capture oil droplets through a medium, making them suitable for treating dispersed and emulsified oils13. Electrochemical processes use electrolysis to remove oily substances, ideal for wastewater with high concentrations of emulsified oils14,15. Adsorption processes use porous materials, such as activated carbon, to adsorb oil droplets, effective for treating various forms of oily contaminants16,17.

Each method has specific applications, but they also have significant limitations. Coagulation/flocculation processes require the use of chemical agents, which can generate secondary pollution and increase treatment costs. Biological treatment is time-consuming and requires specific environmental conditions (e.g., temperature and pH), making it less effective for high-concentration oily wastewater. Filtration processes are limited by the physical properties of the filtration medium and require frequent replacement of filters, leading to high operational costs. Electrochemical processes consume significant energy and generate secondary pollutants such as sludge, and they are less effective for low-concentration oily wastewater. In contrast, adsorption is cost-effective, efficient, and environmentally friendly. It can effectively remove various forms of oil pollutants, including dissolved, dispersed, and emulsified oils. The adsorbent materials can often be regenerated and reused, further reducing treatment costs.

Hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) is a thermochemical process that converts biomass or organic waste into hydrochar with distinct properties in an aqueous environment18,19. HTC can be conducted at relatively low temperatures (150–375 °C) and under self-generated pressure, offering advantages such as low energy consumption, no gas emissions, high carbon yield, and no need for material dehydration20. The chemical structure of the biomass and the hydrothermal reaction conditions significantly affect the properties of the product, such as morphology, pore structure, and surface functional group distribution21. HTC has great potential in wastewater treatment. This study uses Waste biomass, such as sweet potato residue, Indian mallow (widely distributed globally), and Nan bamboo (known for its short growth cycle and high yield in China), to prepare hydrochar for the adsorption treatment of oily wastewater.

Materials and methods

Materials

Sweet potato residue, Indian mallow, and Nan bamboo were collected from Xianning District, Xianning City, Hubei Province. Diesel was purchased from a local gas station. N-hexane and activated carbon (analytical pure) were purchased from Yongda Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. in Tianjin. HCl (analytical pure), NaOH (analytical pure), HNO3, H3PO4 (analytical pure), hydrogen peroxide (analytical pure), KMnO4 (analytical pure) was purchased from KeLong Chemical Co., Ltd. in Chengdu.

Research approach

The research content of this experiment includes the following aspects:

-

(1)

Preparation of hydrochar from sweet potato residue, Indian mallow, and Nan bamboo using hydrothermal carbonization;

-

(2)

Characterization of hydrochar samples using field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and X-ray diffraction (XRD);

-

(3)

Determination of diesel adsorption performance by hydrochar using a UV spectrophotometer;

-

(4)

Examination of the impact of dosage, initial diesel concentration, pH, and contact time on diesel adsorption through single-factor experiments;

-

(5)

Optimization of adsorption conditions through response surface optimization;

-

(6)

Study of the adsorption kinetics and isothermal adsorption patterns of diesel by hydrochar;

-

(7)

Investigation of the modification and regeneration performance of hydrochar.

The research approach is shown in Fig. 1:

This study investigates how hydrochar preparation conditions affect its adsorption performance, with a focus on two key parameters: temperature and solid-liquid ratio. The experiment used sweet potato residue, Indian mallow, and Nan bamboo as raw materials. Hydrothermal carbonization reactions were carried out at temperature gradients of 180 °C, 200 °C, 220 °C, 240 °C, and 260 °C, and solid-liquid ratios ranging from 1:4 to 1:8, with a reaction time of 8 h for each condition. After the reactions, the products were filtered, dried, ground, and sieved to 80 mesh to obtain hydrochar samples for each condition.

Experimental methods

Adsorption amount and removal rate

The specific formulas for adsorption amount and removal rate are as follows:

Adsorption Amount:

Removal Rate:

In the formulas, Q is the adsorption amount with units of mg·g− 1; E % is the removal rate; C0 is the initial concentration of the solution, with units of mg·L− 1; Ct is the concentration of the solution at time t, with units of mg·L− 1; V is the volume of the adsorbed solution, with units of L; m is the mass of the adsorbent, with units of g.

Single-factor experiments

The impact of hydrochar dosage on adsorption effects

In this study, the dosage of adsorbents is a crucial variable in evaluating their effect on oily wastewater treatment. This experiment aims to investigate the influence of varying amounts of SPRH, IMH, and NBH on the adsorption efficiency of oily wastewater. In this experiment, 0.02 g, 0.04 g, 0.06 g, 0.08 g, 0.10 g, 0.12 g, 0.14 g, 0.16 g, 0.18 g, and 0.20 g of adsorbents were added to 50 mL of oily wastewater. The initial concentration of the wastewater was 500 mg·L− 1, with a pH of 7 and a mineralization degree of 4000 mg·L− 1. The experiment was carried out in a constant temperature water bath at 25 °C, with shaking for 120 min. The optimal dosage of each hydrochar was determined based on a comprehensive evaluation of adsorption efficiency and economic cost.

The impact of initial concentration on adsorption effects

SPRH, IMH, and NBH were added at their optimal dosages to simulated oily wastewater at concentrations of 200 mg·L− 1, 300 mg·L− 1, 400 mg·L− 1, 500 mg·L− 1, 600 mg·L− 1, and 700 mg·L− 1, maintaining a pH of 7 and a mineralization degree of 4000 mg·L− 1. The water bath was maintained at 25 °C, and the contact time was 120 min.

The impact of pH on adsorption effects

50 mL of simulated oily wastewater with an initial diesel concentration of 500 mg·L− 1 and a mineralization degree of 4000 mg·L− 1 was taken, the pH of the solution was adjusted to a range of 2–11, and the optimal dosages of SPRH, IMH, and NBH were added. Adsorption was performed under shaking conditions at 25 °C for 120 min. The optimal adsorption pH for each type of hydrochar was determined based on the adsorption effects, after comprehensive evaluation.

The impact of contact time on adsorption effects

Add SPRH, IMH, and NBH at their optimal adsorption dosages and pH values to 50 mL of simulated oily wastewater, which has a diesel concentration of 500 mg·L− 1 and a mineralization degree of 4000 mg·L− 1. Set the water bath temperature to 25 °C, then measure the diesel adsorption capacity and removal efficiency at various adsorption times.

Adsorption kinetics

Adsorption kinetics are determined by factors such as adsorption speed, desorption speed, interactions between adsorbent and adsorbate, temperature, and pressure. To gain a deeper understanding of the adsorption mechanism, data fitting was performed using pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, intraparticle diffusion, and Elovich models to understand the adsorption kinetics characteristics. The specific equations are as follows:

Pseudo-first-order kinetic equation:

Its linear form:

Pseudo-second-order kinetic equation:

Its linear form:

In the formulas, qe and qt represent the adsorption amounts at equilibrium and time t, respectively, with units of mg·g− 1; t is the adsorption time in minutes; k1 is the pseudo-first-order kinetic rate constant with units of min− 1; k2 is the pseudo-second-order kinetic rate constant with units of g·mg− 1·min− 1.

Intraparticle diffusion model:

where C is a constant related to the thickness and boundary layer of the adsorbent. If the plot of qt versus \(\:{t}^{\frac{1}{2}}\) is a straight line passing through the origin, it indicates that intraparticle diffusion is the sole rate-controlling step.

Elovich model:

where \(\:\alpha\:\) and \(\:\beta\:\) are Elovich constants, representing the initial adsorption rate and desorption constant, respectively, which can be obtained by linear fitting of lnt.

Adsorption isotherms

In a solid-liquid system at a constant temperature, the adsorption potential is assumed to remain constant, while the adsorption capacity depends on the liquid-phase concentration. This relationship is termed the adsorption isotherm. Different combinations of adsorbent surfaces and adsorbates result in distinct adsorption isotherms. The shape of these isotherms reflects the adsorbent surface structure, pore characteristics, and interactions between the adsorbent and adsorbate. Analyzing these isotherms allows for understanding adsorption interactions and characterizing the adsorbent surface. Several isotherm models for pollutant adsorption on solid surfaces have been developed based on various adsorption theories and mechanisms: (1) Henry model; (2) Freundlich model; (3) Langmuir model; (4) Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) model; (5) Polanyi-Mance (PMM) model; (6) Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R) model, and (7) Temkin model.

Adsorption isotherms illustrate the adsorption capacity of the adsorbent. An adsorption isotherm curve represents the equilibrium relationship between the concentrations of solute molecules in the adsorbent and solution phases at a given temperature. This study utilizes three widely accepted isothermal adsorption models: Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin, as detailed in the following equations:

Langmuir isothermal adsorption model:

Freundlich isothermal adsorption model:

Where qe represents the equilibrium adsorption amount with units of mg·g− 1; Ce represents the equilibrium concentration with units of mg·L− 1; qmax represents the theoretical maximum adsorption amount with units of mg·g− 1; KL and KF are adsorption rate constants.

Temkin model:

Where R is the gas constant (8.314 J·mol− 1·K− 1), T is the absolute temperature, KT is a constant, and Ce is the concentration at adsorption equilibrium.

Adsorption thermodynamics

Adsorption thermodynamics is commonly employed to simulate parameter variations during the adsorption process. It also encompasses the calculation of ΔGθ, ΔSθ, and ΔHθ for the adsorption reaction through the following equations:

The equilibrium constant Kd is a dimensionless quantity. R is 8.314 J/(mol·K), and T(K) represents the absolute temperature. By plotting 1/T on the x-axis and lnKd on the y-axis, ΔSθ and ΔHθ can be determined from the slope and intercept of the resulting line. Subsequently, the ΔGθ of the adsorption reaction can be calculated using the established formula.

Modification and regeneration of hydrochar

Modification of hydrochar

This study aims to enhance the efficiency of the HTC process of waste biomass and produce hydrochar with improved quality by incorporating appropriate modifiers. The introduction of modifiers aims to introduce oxygen- or nitrogen-containing functional groups on the surface of hydrochar and/or increase its specific surface area, thereby improving its adsorption capacity22,23,24. In this study, the NBH, which exhibited the highest adsorption capacity among the three types of hydrochar, was selected for modification. Four chemical activators were used to enhance the adsorption capacity of NBH: 2 mol·L− 1 nitric acid, 2 mol·L− 1 phosphoric acid, 30% hydrogen peroxide, and 5 g·L− 1 potassium permanganate solution. First, the NBH sample (80 mesh) was immersed in a 2 mol·L− 1 activator solution. The samples were then placed in a temperature-controlled water bath oscillator set to 140 r·min− 1 and maintained for 5 h. After activation, the hydrochar was washed with distilled water until the wash solution’s pH was near neutral. The washed NBH was then placed in an electric drying oven and dried at 105 °C for 4 h. After drying, the samples were ground through an 80-mesh sieve to obtain NBH samples treated with four different modifiers.

Regeneration of hydrochar

Hydrochar is an effective material for pollutant adsorption and purification, with significant potential for applications in environmental management. However, this technology faces several challenges in practical use. Specifically, when hydrochar reaches adsorption saturation and is disposed of improperly, it generates large amounts of waste. This not only requires substantial landfill space but can also cause secondary environmental pollution if incinerated, thereby increasing the costs and resource consumption associated with environmental management.

In evaluating the cost of hydrochar production, it is essential to consider not only its preparation method and adsorption performance but also its regenerative capacity25,26. Solvent regeneration is an effective method for restoring hydrochar’s adsorption capacity. It disrupts the phase equilibrium between the adsorbate, hydrochar, and solvent by altering chemical conditions (e.g., temperature, solvent type, pH), which encourages the adsorbate to detach from the hydrochar surface, thereby restoring its adsorption performance.

This study uses a 0.1 mol·L− 1 NaOH solution as the eluent to investigate the recycling of unmodified NBH. The study aims to optimize elution conditions for efficient hydrochar regeneration, providing a scientific foundation for its sustainable use.

Results and discussion

Optimal Preparation conditions for hydrochar

Weigh 0.08 g of three types of hydrochar, each prepared under different conditions, and add them to 50 mL of simulated oily wastewater with an initial concentration of 600 mg·L− 1, pH 7, and a mineralization degree of 4000 mg·L− 1. Then, agitate the mixture at 25 °C for 120 min to facilitate adsorption. Compare the diesel adsorption capacity of the three hydrochar types prepared under different conditions. The three hydrochar types discussed in this study were prepared under optimal temperature and solid-liquid ratio conditions.

The data in Fig. 2a illustrate the trend of diesel adsorption capacity of SPRH as a function of temperature. Below 200 °C, the adsorption capacity increases with temperature, rising from 133.95 to 161.53 mg·g− 1. However, when the temperature exceeds 200 °C, the adsorption capacity decreases. This suggests that 200 °C is the optimal temperature for SPRH preparation. Furthermore, Fig. 3a shows that as the solid-liquid ratio increases, the diesel adsorption capacity of SPRH rises initially, reaching a peak of 168.27 mg·g− 1 at a solid-liquid ratio of 1:6, before decreasing. Therefore, a solid-liquid ratio of 1:6 is considered optimal for SPRH preparation.

The data in Fig. 2b show that the diesel adsorption capacity of IMH increases with temperature up to 200 °C, rising from 123.85 mg·g− 1 to 143.46 mg·g− 1. Beyond 200 °C, the adsorption capacity declines, suggesting that 200 °C is the optimal temperature for IMH preparation. Figure 3b shows that as the solid-liquid ratio increases, the diesel adsorption capacity of IMH initially rises, peaks at 155.18 mg·g− 1 at a ratio of 1:6, and then decreases. Thus, a solid-liquid ratio of 1:6 is optimal for IMH preparation.

Figure 2c shows the relationship between the diesel adsorption capacity of NBH and temperature. Below 220 °C, the adsorption capacity increases with temperature, rising from 153.16 mg·g− 1 to 179.49 mg·g-1. Above 220 °C, the adsorption capacity declines, suggesting that 220 °C is the optimal temperature for NBH preparation. Figure 3c further illustrates that as the solid-liquid ratio increases, the diesel adsorption capacity of NBH first rises, peaks at 191.64 mg·g− 1 at a 1:6 ratio, and then declines. Thus, a 1:6 solid-liquid ratio is optimal for NBH preparation.

Characterization analysis of hydrochar

SEM characterization results

Figures 4a and b show the SEM images of sweet potato residue (raw material) and SPRH. The sweet potato residue (raw material) exhibits a smooth, spherical structure, which transforms into a loose, porous structure after hydrothermal carbonization. Figures 4c and d show the SEM images of Indian mallow (raw material) and IMH. The Indian mallow raw material exhibits a layered fibrous structure, with small charcoal balls on its surface, which are smooth. After hydrothermal carbonization at 200 °C, the raw material’s surface becomes irregular, and its pores are more dispersed. This change is attributed to the dissolution of part of the cellulose from the charcoal skeleton during the hydrolysis reaction27. Figure 4e and f show the SEM images of the Nan bamboo raw material and NBH. The Nan bamboo raw material exhibits a regular, slender fibrous structure, and, after hydrothermal carbonization, it displays a regular porous structure.

XRD analysis results

X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis is a key technique for studying the internal crystalline structure of materials. Figure 5 shows that SPRH exhibits distinct diffraction peaks at 2 θ values of 14.93° and 26.56°, indicating that the sweet potato residue possesses a certain degree of crystallinity. The XRD pattern of Indian mallow shows broad, diffuse peaks at 2 θ values of 14.98° and 22.8°, primarily corresponding to the 101 and 002 crystal planes of cellulose. This reflects the presence of cellulose and pentose-containing xylan in the hydrochar structure28,29. The XRD spectrum of NBH shows three prominent characteristic peaks, corresponding to the cellulose crystal planes. This indicates that the hydrochar possesses a well-ordered crystalline structure and demonstrates good chemical stability.

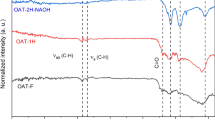

Infrared analysis results

Figure 6 presents the Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of SPRH. The peak at 3410 cm− 1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of the hydroxyl group (–OH), while the absorption peak at 2922 cm− 1 is attributed to the C–H stretching vibration in alkyl groups (–CH3, –CH2). The peak at 1702 cm− 1 is due to the stretching vibration of C = O in ketones, esters, and carboxyl groups. The presence of the O–H vibration at 3410 cm− 1 indicates the presence of –COOH groups in SPRH. Additional characteristic peaks at 1618 cm− 1, 1511 cm− 1, and 1400 cm− 1 correspond to the benzene ring structure, and C–O stretching vibrations in alcohols and phenols (1000–1500 cm− 1). The absorption peak at 781 cm− 1 is related to the bending vibration of the aromatic C–H bond. These results suggest that hydrothermal carbonization has introduced a variety of oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface of sweet potato residue30.

The characteristic peak at 3404 cm− 1 in IMH corresponds to the stretching vibration of the hydroxyl group, and the broad spectral range is attributed to the presence of strong hydrogen bonds. The absorption peak at 2919 cm− 1 results from the stretching vibration of the alkyl C–H bond (found in alkane –CH3, –CH2), while the stretching vibration of C–O in alcohols and phenols appears between 1000 cm− 1 and 1500 cm− 1. The hydrothermal carbonization of Indian mallow did not fully degrade the hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin present in the plant31,32.

The characteristic peak at 3398 cm− 1 in NBH corresponds to the stretching vibration of the hydroxyl group, while the peak at 2906 cm− 1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of the alkyl C–H bond (in alkanes such as –CH3 and –CH2). Additionally, the absorption peak at 1708 cm− 1 is attributed to the stretching vibration of C = O in ketones, esters, and carboxyl groups. The O–H vibration absorption peak at 3398 cm−1 further indicates that NBH contains –COOH groups. The characteristic peaks at 1618 cm− 1, 1508 cm− 1, and 1405 cm− 1 are attributed to the benzene ring structure and the stretching vibration of C–O in alcohols and phenols (between 1000 cm− 1 and 1500 cm− 1). Additionally, an absorption peak at 617 cm− 1 is observed, corresponding to the out-of-plane bending vibration of = C–H on the aromatic ring33. Based on the above analysis, it can be concluded that hydrothermal carbonization leads to the formation of abundant oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface of Nan bamboo34,35,36.

Single-factor experiments

Adsorbent dosage

This study systematically investigates the effect of adsorbent dosage on the adsorption performance of SPRH for diesel. Figure 7 illustrates the relationship between hydrochar dosage and adsorption capacity.

As the SPRH dosage increased from 0.02 g to 0.10 g, the diesel removal rate increased significantly, from 43.85 to 70.22%. However, when the dosage exceeded 0.10 g, the removal rate leveled off. Meanwhile, the adsorption capacity gradually decreased with increasing dosage, from 438.53 to 140.44 mg·g− 1. For the IMH dosage study, the diesel removal rate increased with increasing IMH dosage. When the dosage exceeded 0.08 g, the removal rate leveled off. The adsorption capacity decreased with increasing dosage, from 219.90 to 159.75 mg·g− 1. In the NBH dosage study, as the dosage increased from 0.02 to 0.10 g, the removal rate rapidly increased from 48.36 to 75.16%, with the adsorption capacity reaching 187.91 mg·g− 1. As the dosage continued to increase, the removal rate plateaued, and adsorption reached equilibrium.

This phenomenon occurs because, with a constant diesel concentration, as the adsorbent dosage increases, the adsorption sites on the surface of the simulated oily wastewater solution transition from an initially unsaturated state to near saturation37,38. As the adsorption process approaches equilibrium, further increases in adsorbent dosage do not significantly improve the removal rate39.

For resource conservation and economic efficiency, the optimal SPRH dosage is 0.10 g (2.0 g·L− 1), yielding an adsorption capacity of 140.44 mg·g− 1; the optimal IMH dosage is 0.08 g (1.6 g·L− 1), with an adsorption capacity of 159.75 mg·g− 1; the optimal NBH dosage is 0.10 g (2.0 g·L− 1), achieving a diesel removal rate of 75.16% and an adsorption capacity of 187.91 mg·g− 1.

At this dosage, hydrochar achieves high diesel removal efficiency while minimizing resource waste and cost increase from excessive dosage40. These findings provide an important reference for optimizing adsorbent dosages in practical wastewater treatment processes.

Initial concentration

The study of SPRH’s effect on diesel adsorption, shown in Fig. 8, revealed that as the initial diesel concentration increased from 200 to 500 mg·L− 1, the adsorption capacity of SPRH increased from 76.82 to 160.51 mg·g− 1, while the diesel removal rate decreased from 70.11 to 47.52%. The effect of IMH on diesel adsorption, shown in the figure, indicated that as the initial diesel concentration increased from 200 to 400 mg·L− 1, the adsorption capacity of IMH increased from 77.32 to 145.34 mg·g− 1, while the diesel removal rate decreased from 61.86 to 58.13%. The study on the effect of NBH on diesel adsorption (as shown in the figure) showed that when the initial diesel concentration was 500 mg·L− 1, the diesel removal rate reached 72.91%. As the diesel concentration increased, the removal rate decreased, with a notable decrease to 44.91% when the concentration reached 800 mg·L− 1. To maximize the effectiveness of the NBH adsorbent and ensure a high removal rate of oily wastewater, the optimal initial concentration of simulated oily wastewater was determined to be 500 mg·L− 1.

This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that as diesel concentration increases, the number of active sites on the hydrochar becomes insufficient, resulting in competitive adsorption41,42. When the initial diesel concentration is too high, the adsorption rate of hydrochar decreases due to the saturation of effective sites, causing the interaction between diesel and hydrochar to enter a slow absorption phase43.

pH

In the study on the impact of pH on the adsorption performance of SPRH for diesel, as shown in Fig. 9-a, solution pH significantly influences both the form of diesel in simulated oily wastewater and the chemical properties of the hydrochar surface44. Specifically, the acidity or alkalinity of the solution alters the activity of chemical functional groups on the hydrochar surface. Experimental data show that when pH is below 4, the adsorption performance of SPRH for diesel improves with increasing pH, suggesting that adsorption sites on hydrochar are more active at lower pH. At pH 4, the removal rate and adsorption capacity of SPRH for diesel peak at 67.72% and 169.25 mg·g− 1, respectively. However, when pH exceeds 4, both removal rate and adsorption capacity of SPRH for diesel decrease significantly45,46. This may be due to the passivation of active sites on the hydrochar surface at higher pH, resulting in decreased adsorption capacity. Therefore, in practical applications, the optimal adsorption pH is 4, balancing both adsorption efficiency and cost-effectiveness, maximizing performance while minimizing resource consumption and treatment costs.

The study on the effect of pH on the adsorption performance of IMH for diesel, shown in Fig. 9-b, reveals that at pH 3, the removal rate and adsorption capacity peak at 60.52% and 151.29 mg·g− 1, respectively. When pH exceeds 3, removal rate decreases with increasing pH. Thus, the optimal pH for the removal rate of simulated oily wastewater is determined to be 3.

In the study of pH’s impact on the adsorption performance of NBH for diesel, results in Fig. 9-c show that at pH 4, the removal rate and adsorption capacity reach peak values of 72.62% and 176.84 mg·g− 1, respectively. As pH increases to 11, removal rate and adsorption capacity decrease to 33.58% and 94.86 mg·g− 1, respectively. Considering the removal rate of simulated oily wastewater, the optimal pH is determined to be 4.

Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that pH variations significantly influence the adsorption capacity of hydrochar. For instance, a study on the hydrothermal carbonization of microcrystalline cellulose found that both the yield and carbon fixation rate of hydrochar decrease with increasing acidity. Moreover, the aromaticity of hydrochar is maximized under acidic conditions, whereas its hydrophilicity is highest under alkaline conditions. This further reinforces the role of pH in influencing the adsorption performance of hydrochar.

Contact time

This study investigates the effect of adsorption time on the diesel adsorption performance of hydrochar. The results for SPRH are presented in Fig. 10-a. The data in the figure show that, as adsorption time increases, both the adsorption capacity and removal rate of SPRH for diesel increase significantly. Specifically, at 80 min of adsorption time, the adsorption capacity reaches 148.07 mg·g− 1, and the removal rate increases to 59.23%. As adsorption time increases further, the rate of increase in adsorption capacity slows. At 120 min, the adsorption capacity plateaus at a maximum value of 151.52 mg·g− 1. Based on this analysis, 120 min is considered the optimal adsorption time. The results for IMH are shown in Fig. 10-b. In the initial stage, the diesel removal rate increases significantly with increasing adsorption time. However, after 100 min, the increase slows, suggesting that 100 min is the optimal contact time for the IMH adsorbent. The results for NBH are shown in Fig. 10-c. From 5 to 40 min, both the removal rate and adsorption capacity increase rapidly from 48.63%, 121.59 mg·g− 1 to 67.15%, 167.81 mg·g− 1. From 40 to 120 min, the increase slows, with the removal rate and adsorption capacity reaching 73.69%, 184.22 mg·g− 1, after which adsorption reaches equilibrium. Based on these findings, 120 min is the optimal contact time for the NBH adsorbent to adsorb diesel.

This phenomenon is likely due to the abundance of active sites on the surface of hydrochar in the initial adsorption stage, leading to a fast adsorption rate47. As adsorption progresses, the diesel concentration in the solution decreases, reducing the concentration gradient and the driving force for mass transfer48. Additionally, as adsorption proceeds, the active sites on the surface of hydrochar decrease and approach saturation, slowing the increase in diesel adsorption and removal rates until equilibrium is reached49.

Adsorption kinetics

Kinetic analysis of diesel adsorption by SPRH

The experimental data were dynamically fitted to generate Fig. 11, and the kinetic parameters are summarized in Table 1. Figure 11a represents the pseudo-first-order kinetic model, with R2 = 0.9827, qe = 76.23 mg·g−1, and k₁ = 0.0409. Figure 11b represents the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, with R2 = 0.9992, qe = 156.25 mg·g−1, and k2 = 0.0013. Figure 11c represents the intraparticle diffusion model, with R2 = 0.9113. The adsorption process can be divided into two stages: surface adsorption by the adsorbent and slow diffusion within the pores. Neither of the lines passes through the origin, suggesting that intraparticle diffusion alone does not control the adsorption process50,51,52. Figure 11d represents the Elovich kinetic model, with R2 = 0.9509. From Fig. 11b and the correlation coefficient R2, it is evident that the adsorption of SPRH for diesel follows the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, with R2 = 0.9992. The experimental adsorption amount (qe, exp = 151.52 mg·g−1) closely matches the theoretically calculated equilibrium value (qe, cal).

Kinetic analysis of diesel adsorption by IMH

Adsorption dynamics are crucial for understanding the adsorption mechanism. The adsorption of diesel onto IMH at various time intervals was analyzed using the pseudo-first-order model, as shown in Fig. 12; Table 2. Figure 12a shows the pseudo-first-order kinetic model, with R2 = 0.9933, qe = 117.57 mg·g−1, and k₁ = 0.0315. Figure 12b presents the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, with R2 = 0.9952, qe = 163.93 mg·g−1, and k2 = 0.0004 (Fig. 13) . Figure 14c shows the intraparticle diffusion model (R2 = 0.8948), and Fig. 12d illustrates the Elovich kinetic model (R2= 0.9276). Based on Fig. 12b and correlation coefficient (R2), the pseudo-second-order kinetic model better describes adsorption of diesel onto IMH.

Kinetic analysis of diesel adsorption by NBH

The adsorption dynamics were analyzed based on the experimental data, and the fitting results are presented in Fig. 13. The corresponding parameter values are listed in Table 3. Figure 13a shows the pseudo-first-order kinetic model, with R2 = 0.9809, qe=72.33 mg·g−1, and k₁=0.0355. Figure 13b represents the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, with R2 = 0.9997, qe = 188.68 mg·g−1, and k2 = 0.0012. Figure 13c illustrates the intraparticle diffusion model, with R2 = 0.8321. Figure 13d depicts the Elovich kinetic model, with R2 = 0.9657. By analyzing Figs. 13b and the corresponding correlation coefficients (R2), it is evident that R2 reaches 0.9997. The measured adsorption capacity (q,eexp = 189.34 mg·g−1) is close to the theoretically calculated equilibrium adsorption capacity (q,ecal = 191.68 mg·g−1). This suggests that the pseudo-second-order kinetic model more accurately describes the entire process of NBH adsorbing diesel. Therefore, the diesel adsorption process on hydrochar is primarily governed by chemical adsorption mechanisms, including electron sharing or transfer, particle diffusion, surface adsorption, liquid film diffusion, and other steps.

Adsorption isotherms

Adsorption isotherms of diesel adsorption by SPRH

The isothermal adsorption data of hydrochar for diesel were fitted to the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin models. The fitting results are presented in Fig. 14, with the corresponding parameter values listed in Table 4. From Fig. 15; Table 4, it can be observed that the Langmuir model provides a better fit, with an R2 value of 0.9898. Additionally, the theoretical maximum adsorption capacity closely matches the experimentally measured value, suggesting that the adsorption of diesel on SPRH is predominantly monolayer adsorption.

Adsorption isotherms of diesel adsorption by IMH

Figures 16; Table 5 display the adsorption isotherms and the results of parameter fitting for IMH adsorption of diesel. The results indicate that, compared to the Freundlich and Temkin models, the Langmuir model has an R2 value closer to 1. Additionally, the theoretically calculated maximum adsorption (188.89 mg·g− 1) closely matches the experimentally measured maximum adsorption (154.34 mg·g− 1), suggesting that the IMH adsorption of diesel follows a monolayer adsorption process.

Adsorption isotherms of diesel adsorption by NBH

The fitting results and adsorption isotherms of NBH are shown in Figs. 16; Table 6. The Langmuir correlation coefficient (R2) is higher, suggesting that the adsorption of NBH on diesel more closely follows the Langmuir model, with a theoretical adsorption capacity of 227.51 mg·g− 1. In the Langmuir isothermal adsorption model, the dimensionless coefficient RL indicates the ease of the adsorption process. The equation for RL is: RL= 1/(1 + KLC0), where C₀ represents the initial concentration of the solution before adsorption. If RL > 1, adsorption is difficult; if 0 < RL < 1, adsorption is relatively easy; if RL = 0, adsorption is irreversible. The calculated RL value for this experiment is 0.1459, which lies between 0 and 1, indicating that the adsorption process is relatively easy.

Response surface analysis

Sweet potato residue hydrochar

The optimal adsorption conditions for SPRH in diesel adsorption, determined from the single-factor experiment, are a dosage of 2.0 g·L− 1, a diesel concentration of 500 mg·L− 1, pH 4, and a contact time of 120 min. To further optimize adsorption conditions, three factors–dosage, initial diesel concentration, and pH–were identified as having the greatest impact on adsorption efficiency. A, B, and C represent the dosage (mg·g− 1), initial diesel concentration (mg·L− 1), and pH, respectively. The response variable (Y) represents the amount of diesel adsorbed by SPRH, and the experimental factors and their corresponding levels are outlined in Table 7.

Through the Box-Behnken central composite design method provided by Design-expert 8.0 software, different combinations of adsorption conditions were obtained, and the adsorption test results are shown in Table 8.

As shown in Table 9, variance analysis of the statistical results using Design-Expert 8.0 software reveals that the model is highly significant (P < 0.0001) (This section analysis software used by full name is Design-Expert, version 8.0, website url is https://www.statease.com/software/design-expert/.), indicating a strong relationship between the response value and each factor. The model has an R2 value of 0.9925 and R2Adj of 0.9827, suggesting that it explains 98.27% of the variation in the response value. The lack of fit is not significant (P = 0.0951, > 0.05), which is favorable for the model and suggests that the regression equation is suitable for analysis. The coefficient of variation (C.V. %) is 2.08, indicating that the model is precise and well-fitting. The software analysis reveals that the factors A, B, C, A2, B2, C2, and the interaction AB are highly significant, while the interactions AC and BC are not significant. A quadratic multiple regression equation was obtained using Design-Expert 8.0 software:

\(\begin{gathered} {\text{Y}}\,=\,{\text{152}}.{\text{46}} - {\text{15}}.{\text{26A}}\,+\,{\text{12}}.{\text{73B}}\,+\,{\text{6}}.{\text{64C}}\,+\,{\text{9}}.{\text{96AB}} \hfill \\ - {\text{1}}.{\text{87AC}}\,+\,0.{\text{53BC}} - {\text{13}}.{\text{99}}{{\text{A}}^{\text{2}}} - {\text{15}}.{\text{31}}{{\text{B}}^{\text{2}}} - {\text{4}}.{\text{55}}{{\text{C}}^{\text{2}}} \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

The response surface curve and contour plot can assess the influence of preparation factors on the adsorption of SPRH onto diesel. An elliptical contour plot indicates a significant interaction between the two factors, while a circular contour plot suggests that the interaction is not significant. Figure 17 presents the response surface curve of SPRH adsorption onto diesel under varying conditions.

Indian Mallow hydrochar

The optimal adsorption conditions for IMH in diesel adsorption, determined from the single-factor experiment, are as follows: a dosage of 1.6 g·L− 1, a diesel concentration of 400 mg·L− 1, a pH of 3, and a contact time of 100 min. To further optimize the adsorption process, three factors were selected for optimization based on their significant impact on adsorption efficiency: dosage, initial diesel concentration, and pH. A, B, and C represent the dosage (mg·g− 1), initial diesel concentration (mg·L− 1), and pH, respectively. The response variable (Y) is defined as the amount of diesel adsorbed by IMH, and the experimental factors and their levels are detailed in Table 10.

Through the Box-Behnken central composite design method provided by Design-expert 8.0 software, different combinations of adsorption conditions were obtained, and the adsorption test results are shown in Table 11.

Table 12 shows the results of the variance analysis conducted using Design-Expert 8.0 software. The model is highly significant (P < 0.0001), suggesting a strong relationship between the response variable and the factors. The model explains 99.16% of the variation in the response value (R2 = 0.9916; R2Adj = 0.9808). The lack of fit (P = 0.0885) is not significant, which supports the validity of the regression model. Additionally, the coefficient of variation (C.V.% = 2.24) indicates high precision and a good fit. Significant factors identified include A, B, C, AB, A2, B2, and C2, while the interaction terms AC and BC are not significant. The quadratic regression equation obtained is as follows:

The response surface curve and contour plot are used to assess the influence of preparation factors on the adsorption of IMH onto diesel. If the contour plot is elliptical, it suggests a significant interaction between the two factors; if circular, it indicates no significant interaction. Figure 18 shows the response surface curve of IMH adsorption on diesel under various conditions.

Single-factor experiments and response surface analysis identified the optimal adsorption conditions for IMH on diesel as follows: a dosage of 1.4 g·L− 1, an initial diesel concentration of 398 mg·L− 1, a pH of 3.18, and an adsorption time of 100 min. The theoretical maximum diesel adsorption capacity was 157.41 mg·g− 1. To verify the reliability of these optimal conditions, repeated adsorption experiments were performed three times. The final adsorption capacity was 154.4 ± 0.56 mg·g− 1, which closely approximates the theoretical maximum value.

Nan bamboo hydrochar

The optimal adsorption conditions for NBH adsorbing diesel, determined from the single-factor experiment, are as follows: a dosage of 2.0 g·L− 1, a diesel concentration of 500 mg·L− 1, a pH of 4, and a contact time of 120 min. To further optimize the adsorption conditions, three key factors–dosage, initial diesel concentration, and pH–were selected based on their significant impact on adsorption efficiency. A, B, and C represent the dosage (mg·g− 1), the initial diesel concentration (mg·L− 1), and pH, respectively. The response variable (Y) represents the adsorption amount of NBH for diesel, with the experimental factors and level schemes outlined in Table 13.

Through the Box-Behnken central composite design method provided by Design-expert 8.0 software, different combinations of adsorption conditions were obtained, and the adsorption test results are shown in Table 14.

According to Table 15, the variance analysis of the statistical results, conducted using Design-Expert 8.0 software, shows that the model is highly significant (P < 0.0001), meaning there is a strong relationship between the response value and each factor. The model’s statistical significance is confirmed by the following: R2 = 0.9889 and R2Adj = 0.9747, indicating that the model accounts for 98.89% of the variation in the response value. The lack of fit (P = 0.264, > 0.05) is not significant, which supports the adequacy of the regression model for further analysis. Additionally, the coefficient of variation (C.V.% = 1.97) demonstrates high precision and good model fit. The software analysis reveals that factors A, B, A2, and B2 are highly significant, while factors C and C2 are significant. However, interactions AC and BC are not significant. A quadratic multiple regression equation was derived using Design-Expert 8.0 software:

\(\begin{gathered} {\text{Y}}\,=\,{\text{184}}.{\text{33}} - {\text{2}}0.{\text{57A}}\,+\,{\text{15}}.{\text{16B}} - {\text{5}}.{\text{37C}}\,+\,{\text{4}}.{\text{27AB}} \hfill \\ - {\text{1}}.{\text{73AC}} - {\text{2}}.0{\text{4BC}} - {\text{9}}.00{{\text{A}}^{\text{2}}} - {\text{12}}.{\text{88}}{{\text{B}}^{\text{2}}} - {\text{ 8}}.{\text{213}}{{\text{C}}^{\text{2}}} \hfill \\ \end{gathered}\)

The response surface curve diagram of the adsorption amount of NBH for diesel under different adsorption conditions is shown in Fig. 19.

Single-factor experiments and response surface analysis were used to determine the optimal adsorption conditions for NBH on diesel. These conditions are: a dosage of 1.8 g·L− 1, an initial diesel concentration of 502 mg·L− 1, pH 3.92, and an adsorption time of 120 min. The theoretical diesel adsorption capacity is 193.75 mg·g− 1. To confirm the reliability of the optimal adsorption conditions, three repeated adsorption experiments were performed. The final adsorption capacity was 189.7 ± 0.79 mg·g− 1, which is in close agreement with the theoretical value.

Adsorption thermodynamics

Thermodynamic studies were conducted on three types of hydrochar within the temperature range of 298–318 K, as shown in the Fig. 20; Table 16. It can be known that the adsorption processes of the three types of hydrothermal carbons have ΔHθ> 0 and ΔGθ< 0, indicating that the adsorption process is a spontaneous endothermic process regarding removal of oil by hydrochars.

Adsorption mechanism

Hydrothermal carbonization-derived hydrochar exhibits excellent oil adsorption performance, with the adsorption mechanism involving several aspects:

-

(1)

Synergistic physical and chemical adsorption constitutes the primary adsorption mechanism. The hydrochar’s extensive pore structure and large specific surface area provide abundant physical adsorption sites for oil molecules, enabling their adsorption onto the pore inner surfaces. Additionally, the hydrochar surface is rich in functional groups like hydroxyl, carboxyl, carbonyl, and aromatic rings, which can interact chemically with polar groups in oil molecules via hydrogen bonding or electrostatic interactions, thereby facilitating chemisorption.

-

(2)

Surface properties significantly influence hydrochar’s adsorption capacity. While pore structure and specific surface area determine physical adsorption, surface functional group types and contents affect chemisorption. In this study, NBH, with the highest specific surface area and most developed pore structure, offered more adsorption sites and a faster rate, granting it the highest adsorption capacity among the three hydrochars. Its oxygen- and nitrogen-containing functional groups also strongly interacted with oil molecules, further enhancing adsorption. Although SPRH and IMH have less developed surface properties, they still meet certain adsorption requirements.

-

(3)

Thermodynamic and kinetic characteristics of the adsorption process also reveal the adsorption mechanism. Experimental results show that the adsorption process for all three hydrochars is spontaneous and endothermic, indicating that increasing temperature favors the adsorption reaction. Kinetic analysis shows that the adsorption process follows a pseudo-second-order kinetic model, suggesting that chemisorption mechanisms, including electron sharing or transfer and surface adsorption steps, primarily control the process, As shown in the Fig. 21. This highlights that chemical interactions between oil molecules and the hydrochar surface are key factors determining adsorption rate and capacity.

In summary, the adsorption mechanism of hydrochar results from the synergistic action of physical and chemical adsorption. Its well-developed pore structure and rich surface functional groups enable effective oil adsorption. By optimizing hydrochar preparation conditions and surface properties, its adsorption performance can be further improved, offering an efficient solution for oil-polluted wastewater treatment.

Modification and regeneration of Nan bamboo hydrochar

Modification effects

Weigh 0.10 g of each of the four modified hydrochar samples and add them to 50 mL of simulated oily wastewater, which has a concentration of 500 mg·L− 1, a pH of 4, and a mineralization degree of 4000 mg·L− 1. The samples are adsorbed under constant temperature conditions (25 °C) and agitated for 120 min to calculate the removal efficiency and adsorption capacity of the different modified hydrochar samples for diesel. The experimental results are presented in Fig. 22.

As shown in the figure, all four modifiers enhance the unit mass adsorption of NBH for diesel to some extent. Compared to unmodified NBH, the adsorption of diesel by hydrochars modified with KMnO4, H2O2, H3PO4, and HNO3 solutions increased by 13.50%, 21.25%, 14.25%, and 12.38%, respectively. Among these, the 30% H2O2 solution had the most significant effect, with an adsorption capacity of 223.37 mg·g− 1. The H2O2 modification increased the oxygen content in the carbon material, the number of surface oxygen-containing functional groups, as well as the specific surface area and pore structure. These effects together enhanced the adsorption performance of hydrochar for diesel.

In this study, we performed a detailed analysis of NBH and its hydrogen peroxide-modified sample using infrared spectroscopy. The results revealed by Fig. 23 that both samples exhibited characteristic absorption peaks corresponding to oxygen-containing functional groups, including hydroxyl groups (3403 cm− 1), carbonyl or carboxyl groups (1612 cm− 1 and 1623 cm− 1), ether bonds or alcohols (1068 cm− 1 and 1028 cm− 1), and aromatic rings (1508 cm− 1 and 1533 cm− 1). Furthermore, the modified NBH sample displayed a more intense absorption peak in the stretching vibration region of the C-H bond (2844 cm− 1), suggesting alterations or an increase in alkyl structures.

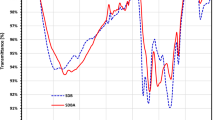

This study compared the NBH sample with one modified by hydrogen peroxide, using XRD technology. The results indicated that while the modification process did not significantly alter the fundamental crystal structure of NBH, noticeable changes were observed in the XRD spectrum of the modified sample. As shown in Fig. 24, the peak intensity of the modified NBH changed, possibly reflecting alterations in crystal size or orientation of crystal faces. Furthermore, the slight shift in peak position may suggest minor changes in lattice parameters, potentially due to the oxidizing action of hydrogen peroxide53, which leads to oxidation of surface carbon atoms and the formation of oxygen-containing functional groups. These chemical and physical structural changes may enhance the material’s adsorption performance and catalytic activity.

The BET analysis of NBH before and after H2O2 modification revealed significant changes in its textural properties, as illustrated in the BET isotherms and pore size distribution plots (Figs. 25 and 26). The NBH exhibited a lower specific surface area of 3.2635 m2/g, which increased to 5.2548 m2/g after H2O2 treatment. This enhancement in surface area is attributed to the creation of additional pores or the enlargement of existing pores due to the oxidative etching effect of H2O2. The increase in surface area provides more accessible sites for adsorbate molecules, thereby improving the material’s adsorption capacity. The total pore volume also showed an improvement, increasing from 0.023271 cm³/g for the NBH to 0.026477 cm³/g for the modified NBH. This suggests that H2O2 treatment not only increased the number of pores but also potentially expanded their dimensions, facilitating the diffusion and adsorption of target molecules. The pore size distribution analysis indicated that the NBH had a wider pore size distribution with an average pore diameter of 28.5227 nm, while the modified NBH exhibited a narrower distribution and a smaller average pore diameter of 20.1546 nm. This narrowing of the pore size distribution may be due to the selective etching of smaller pores by H2O2, which could enhance the material’s suitability for adsorbing specific size ranges of pollutants. The adsorption and desorption isotherms for both samples showed typical Type IV behavior with hysteresis loops, indicating the presence of mesoporous structures. However, the hysteresis loop of the modified hydrochar was more pronounced, suggesting improved mesoporous characteristics. The enhanced microporosity was evident from the significant increase in micropore volume from 0.000020 cm³/g to 0.001975 cm³/g and micropore area from 0.0691 m2/g to 1.7678 m2/g. This increase in microporosity is particularly important for adsorption applications, as micropores are highly effective in capturing smaller molecules through mechanisms such as van der Waals forces and capillary condensation.

By modifying NBH with hydrogen peroxide, we successfully introduced additional oxygen-containing functional groups on its surface, which significantly increased the material’s polarity and its ability to adsorb polar molecules. The modified sample exhibited increased hydrophilicity, which is crucial for enhancing its potential applications in water treatment and gas purification. Additionally, the modification process may increase the material’s specific surface area and enhance its pore structure, providing more active sites for adsorption and potentially improving its capacity to adsorb small molecules54.

In the comparative analysis in Table 17, NBH (H2O2-modified) exhibited a notable adsorption capacity of 223.37 mg/g, significantly surpassing other adsorbents. This substantial increase can be attributed to the introduction of additional oxygen content and surface oxygen-containing functional groups during the modification process. These changes enhance the material’s polarity, thereby improving its adsorption capacity for polar molecules. Additionally, the modification likely increases the material’s specific surface area and refines its pore structure, providing more active sites that further enhance its ability to adsorb small molecules.

Although Crab Shell Biochar exhibits a high adsorption capacity of 480.6 mg/g, its high cost may limit its widespread use in practical applications. In contrast, while SPRH and IMH adsorb relatively lower amounts, they still outperform Wheat Residue, Organo-bentonite, and Org-bentonite, suggesting that these materials could be competitive in specific application scenarios. The unmodified NBH, with an adsorption capacity of 193.75 mg/g, also demonstrates superior performance compared to most other adsorbents, indicating its effectiveness as an adsorption material. This may be attributed to the natural pore structure and surface properties of NBH, which provide it with a strong affinity for oil molecules.

Regeneration effects

The results are shown in Fig. 27. After 4 adsorption/desorption cycles, the adsorption amount can still reach 63.24% of the initial adsorption amount, indicating that the hydrochar prepared by solvent regeneration has good regeneration effects, which can greatly reduce the treatment cost of hydrochar.

Conclusions

This study aims to compare the treatment efficiency of oily wastewater using hydrochars derived from various raw materials (sweet potato residue, Indian mallow, and Nan bamboo) and to assess their modification and regeneration effects. Using hydrothermal carbonization, we prepared three types of hydrochars and characterized them using SEM, FTIR, and XRD to analyze their micromorphology, surface functional groups, and crystal phase structure in detail. The experimental results demonstrate that NBH exhibits the highest adsorption performance, with optimal conditions being a dosage of 1.8 g·L− 1, an initial diesel concentration of 502 mg·L− 1, a pH of 3.92, and an adsorption time of 120 min, achieving a diesel adsorption capacity of 193.75 mg·g− 1. Kinetic studies indicate that the adsorption of all hydrochars follows the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, with a correlation coefficient (R2) near 1, suggesting that the process is primarily governed by chemical adsorption mechanisms. Isothermal adsorption results align with the Langmuir model, with the theoretical maximum adsorption capacity closely matching the experimentally measured value, further confirming monolayer adsorption characteristics.

To further improve the adsorption performance of hydrochars, this study applied four modifiers (KMnO4, H2O2, H3PO4, and HNO3) to modify NBH. The modified hydrochars exhibited significant improvements in adsorption performance, with H2O2 modification yielding the greatest effect, increasing the unit adsorption capacity by 21.25%. These results suggest that chemical modification is an effective approach to enhance hydrochar adsorption performance. Regarding regeneration performance, after four adsorption-desorption cycles, the adsorption capacity of NBH retained 63.24% of its initial capacity, demonstrating that solvent regeneration effectively maintains hydrochar performance and can significantly reduce treatment costs.

In summary, this study not only improved the adsorption performance of NBH through chemical modification but also confirmed its stability and cost-effectiveness over multiple cycles, offering a new strategy for the efficient treatment of oily wastewater.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Kangle Ding, upon reasonable request.The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the sinence data bank repository. [https://www.scidb.cn/en/anonymous/dVVmaUFu]

References

Piyaphong, Y. et al. Y., Enhancement of biodiesel production from soybean oil by electric field and its chemical kinetics. J Chemical Eng. Process. - Process. Intensification 153(C), (2020).

Rahmani, A. et al. Enhanced degradation of furfural by heat-activated persulfate/nzvi-rgo oxidation system; degradation pathway and improving the biodegradability of oil refinery wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Engineering. 8 (6), 104468 (2020).

Sun, Y. et al. Physical pretreatment of petroleum refinery wastewater instead of chemicals addition for collaborative removal of oil and suspended solids. J. Clean. Production. 278, 123821 (2021).

Santos, O. S. H., Silva, M. C., d., Silva, V. R., Mussel, W. N. & Yoshida, M. I. Polyurethane foam impregnated with lignin as a filler for the removal of crude oil from contaminated water. J. Hazard. Materials. 324 (PB), 406–413 (2017).

Cai, Y. et al. Nanofibrous metal–organic framework composite membrane for selective efficient oil/water emulsion separation. J. Membr.Sci.. 543, 10–17 (2017).

Ye, H. et al. Influences of coagulation pretreatment on the characteristics of crude oil electric desalting wastewaters. J Chemosphere. 264 (P2), 128531–128531 (2020).

Ebrahimi, M., Kazemi, H., Mirbagheri, S. A. & Rockaway, T. D. An optimized biological approach for treatment of petroleum refinery wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 4 (3), 3401–3408 (2016).

Dura, A. & Breslin, C. B. Electrocoagulation using aluminium anodes activated with mg, in and Zn alloying elements. J. Hazard. Materials. 366, 39–45 (2019).

Chouchene, A., Jeguirim, M., Trouvé, G., Favre-Reguillon, A. & Buzit, G. L. Combined process for the treatment of Olive oil mill wastewater: Absorption on sawdust and combustion of the impregnated sawdust. J Bioresource Technology. 101 (18), 6962–6971 (2010).

Padmaja, K., Cherukuri, J. & Reddy, M. A. A comparative study of the efficiency of chemical coagulation and electrocoagulation methods in the treatment of pharmaceutical effluent. J. Water Process. Engineering. 34, 101153–101153 (2020).

Anal, C. & Suparna, M. Treatment of hydrocarbon-rich wastewater using oil degrading bacteria and phototrophic microorganisms in rotating biological contactor: effect of n:p ratio. J. Hazard. Materials. 154 (1–3), 63–72 (2008).

Li, L. et al. Research on the enhancement of biological nitrogen removal at low temperatures from ammonium-rich wastewater by the bio-electrocoagulation technology in lab-scale systems, pilot-scale systems and a full-scale industrial wastewater treatment plant. J. Water Res.. 140, 77–89 (2018).

Tan, W. et al. Coalescence behavior of oil droplets in wastewater during membrane separation. J. Chem. Eng. Res. Design. 204, 11–19 (2024).

Atousa, G. K. et al. Electrochemical-based processes for produced water and oily wastewater treatment: A review. J. Chemosphere. 338, 139565–139565 (2023).

Rakhmania, Hesam, K. et al. Electrochemical oxidation of palm oil mill effluent using platinum as anode: Optimization using response surface methodology. J Environmental Research. 214 (P3), 113993–113993 (2022).

Kun, W., Yuanyuan, C., Yongqiang, O., Hang, L. & Ting, L. Adsorptive removal of fluoride from water by granular zirconium-aluminum hybrid adsorbent: Performance and mechanisms. J Environmental Sci. Pollution Res. International. 25 (16), 15390–15403 (2018).

Zhang, W. et al. Synthesis of mixed-base active material from drilling fluid solid waste and biomass for oil wastewater adsorption and its mechanism. J. Water Process. Engineering. 66, 106076–106076 (2024).

Jain, A., Balasubramanian, R. & Srinivasan, M. P. Hydrothermal conversion of biomass waste to activated carbon with high porosity: A review. J. Chemical Engineering Journal. 283, 789–805 (2016).

Parshetti, G. K., Chowdhury, S. & Balasubramanian, R. Hydrothermal conversion of urban food waste to Chars for removal of textile dyes from contaminated waters. J Bioresource Technology. 161, 310–319 (2014).

Kalderis, D., Kotti, M. S., Méndez, A. & Gascó, G. Characterization of hydrochars produced by hydrothermal carbonization of rice husk. J Solid Earth. 5 (1), 477–483 (2014).

Carlos, N. et al. The role of oxygenated functional groups on cadmium removal using pyrochar and hydrochar derived from guadua angustifolia residues. J Water. 15 (3), 525–525 (2023).

Qiao, Y., Liu, X., Zhu, H., Zhang, S. & Shen, L. Kmno4 modified magnetic hydrochar for efficient adsorption of malachite green and methylene blue from the aquatic environment. J. Industrial Eng. Chemistry. 139, 302–312 (2024).

Tian, X., Sun, A., Wang, C. & Ding, K. Removal of Quinoline in aqueous solutions using chemically modified and unmodified hydrochars from lotus seedpods: A comprehensive experimental study. J Colloids Surf. A: Physicochemical Eng. Aspects. 702 (P2), 135166–135166 (2024).

Zhong, H. et al. Efficient adsorption removal of carbamazepine from water by dual-activator modified hydrochar. J Separation Purif. Technology. 353 (PB), 128287–128287 (2025).

Wang, Y., Wu, G., Zhang, Y., Su, Y. & Zhang, H. The deactivation mechanisms, regeneration methods and devices of activated carbon in applications. J. Clean. Production. 476, 143751–143751 (2024).

Ranjbar, E., Ahmadi, F. & Baghdadi, M. Regeneration of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (pfos) loaded granular activated carbon using organic/inorganic mixed solutions. J Chemical Eng. Science. 300, 120623–120623 (2024).

Amine, A. A., Besma, K., Salah, J., Matei, G. C. & Mejdi, J. Hydrochars production, characterization and application for wastewater treatment: A review. J Renewable Sustainable Energy Reviews 127, (2020).

Klaudia, C., Maciej, Ś. & Małgorzata, W. Hydrothermal carbonization process: Fundamentals, main parameter characteristics and possible applications including an effective method of sars-cov-2 mitigation in sewage sludge. A review. J. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 154, (2022).

Liu, F., Yu, R. & Guo, M. Hydrothermal carbonization of forestry residues: Influence of reaction temperature on holocellulose-derived hydrochar properties. J. Mater. Science. 52 (3), 1736–1746 (2017).

Xu, H. et al. Comprehensive study on the hydrochar for adsorption of cd(ii): Preparation, characterization, and mechanisms. J Environmental Sci. Pollution Res. International. 30 (23), 64221–64232 (2023).

Chen, Y. X. et al. Green wood bio-adhesives from cellulose-derived bamboo powder hydrochars. J Chemical Eng. Journal. 498, 155667–155667 (2024).

Yang, F. et al. Effect of cellulose-lignin ratio on the adsorption of u(vi) by hydrothermal charcoals prepared from dendrocalamus farinosus. J. Frontiers in Environmental Science. 12, 1451496–1451496 (2024).

Yan, L. et al. The integrated production of hydrochar and methane from lignocellulosic fermentative residue coupling hydrothermal carbonization with anaerobic digestion. J Chemosphere. 340, 139929–139929 (2023).

Cui, D. et al. From sewage sludge and lignocellulose to hydrochar by co-hydrothermal carbonization: mechanism and combustion characteristics. J Energy. 305, 132414–132414 (2024).

Inkoua, S. et al. Unveiling drastic influence of cross-interactions in hydrothermal carbonization of spirulina with cellulose, lignin or Poplar on nature of hydrochar and activated carbon. J. Environ. Management. 366, 121713–121713 (2024).

Ziyun, L. et al. Behaviors and interactions during hydrothermal carbonization of protein, cellulose and lignin. J Chemical Eng. Journal 476, (2023).

Fliri, L. et al. Identification of a Polyfuran network as the initial carbonization intermediate in cellulose pyrolysis: A comparative analysis with cellulosic hydrochars. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 181, 106591 (2024).

Kostyniuk, A. & Likozar, B. Wet torrefaction of biomass waste into levulinic acid and high-quality hydrochar using h-beta zeolite catalyst. J. Clean. Production. 449, 141735 (2024).

H, F. H. & Marianne, N. Exploitation of expired cellulose biopolymers as hydrochars for capturing emerging contaminants from water. J RSC Advances. 13 (29), 19757–19769 (2023).

Betül, E., Koray, A., Suat, U. & Selhan, K. Comparative studies of hydrochars and biochars produced from lignocellulosic biomass via hydrothermal carbonization, torrefaction and pyrolysis. J. Energy Institute 109, (2023).

Shijie, Y., Xiaoxiao, Y., Qinghai, L., Yanguo, Z. & Hui, Z. Breaking the temperature limit of hydrothermal carbonization of lignocellulosic biomass by decoupling temperature and pressure. J Green Energy & Environment. 8 (4), 1216–1227 (2023).

Xinkun, Z. et al. Preparation of n-doped cellulose-based hydrothermal carbon using a two-step hydrothermal induction assembly method for the efficient removal of cr(vi) from wastewater. J Environmental Research. 219, 115015–115015 (2023).

T., T., S., M., N., M., A., M., A., R., A., L., Low-temperature hydrothermal carbonization of activated carbon microsphere derived from microcrystalline cellulose as carbon dioxide (co2) adsorbent. J. Materials Today Sustainability. 23, (2023).

Betül, E., Suat, O. A. Y., Kubilay, U. & Selhan, T. Production of hydrochars from lignocellulosic biomass with and without boric acid. J Chemical Eng. & Technology. 45 (11), 2112–2122 (2022).

Ruikun, W. et al. Effect of lignocellulosic components on the hydrothermal carbonization reaction pathway and product properties of protein. J Energy 259, (2022).

Liu, Z., Zhang, Y. & Liu, Z. Comparative production of biochars from corn stalk and cow manure. J Bioresource Technology 291, (2019).

Haisheng, L., Lijun, Z., Shu, Z., Qingyin, L. & Xun, H. Hydrothermal carbonization of cellulose in aqueous phase of bio-oil: the significant impacts on properties of hydrochar. J Fuel 315, (2022).

Yi, W., Huihui, W., Xueqin, Z. & Chuanfu, L. Ammonia-assisted hydrothermal carbon material with schiff base structures synthesized from factory waste hemicelluloses for cr(vi) adsorption. J. Environ. Chem. Engineering 9(5), (2021).

Ghada, M., Ola, E. S. & Nady, F. Preparation of carbonaceous hydrochar adsorbents from cellulose and lignin derived from rice straw. J Egyptian J. Chemistry. 60 (5), 8–9 (2017).

Hanifrahmawan, S., Budhijanto, B., Lisendra, M., Fatih, G. & Arief, B. Kinetic and thermodynamic evidences of the diels-alder cycloaddition and Pechmann condensation as key mechanisms of hydrochar formation during hydrothermal conversion of lignin-cellulose. J Chemical Eng. Journal. 480, 148116 (2024).

Eloise, B., Giulio, S. & Mauro, L. Kinetic modelling of the hydrothermal carbonisation of the macromolecular components in lignocellulosic biomass. J Bioresource Technol. Reports 24, (2023).

Zhao, Y. et al. A simple two-step reaction for synthesizing demulsifiers for a high salt crude oil emulsion. J Separation Purif. Technology 359, (2025).

Stankovich, S. et al. Synthesis of graphene-based nanosheets via chemical reduction of exfoliated graphite oxide. J Carbon. 45 (7), 1558–1565 (2007).

Xiaojie, F. et al. Directional regulation and mechanism analysis of the surface properties of hydrothermal carbon by Circulating liquid in the hydrothermal carbonization procedure. J Environmental Research. 229, 116003–116003 (2023).

Jiang, Y. F., Sun, H., Yves, U. J., Li, H. & Hu, X. F. Impact of Biochar produced from post-harvest residue on the adsorption behavior of diesel oil on loess soil. J Environmental Geochem. Health. 38 (1), 243–253 (2015).

Han, X. et al. Facile Preparation of a porous Biochar derived from waste crab shell with high removal performance for diesel. J. Renew. Materials. 9 (8), 1377–1391 (2021).

Emam, E. A. Modified activated carbon and bentonite used to adsorb petroleum hydrocarbons emulsified in aqueous solution. J American J. Environ. Protection 2(6), (2013).

Rajakovic, V., Aleksic, G., Radetic, M. & Rajakovic, L. Efficiency of oil removal from real wastewater with different sorbent materials. J. Hazard. Materials. 143 (1–2), 494–499 (2007).

Yu, Z. et al. Adsorption of diesel oil onto natural mud shale: from experimental investigation to thermodynamic and kinetic modelling. J International J. Environ. Anal. Chemistry. 103 (15), 3468–3482 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wang contributed to investigation, data analysis, drafting, and reviewing and editing. Xiao contributed to methodology, investigation, and conceptualization. Li contributed to investigation, validation, data collection, drafting, and reviewing. Tian contributed to data curation, formal analysis, and reviewing and editing. Xu contributed to methodology, investigation, and formal analysis. Ding contributed to conceptualization, methodology development, project administration, supervision, and reviewing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, C., Xiao, W., Li, Q. et al. Oil removal from wastewater with biomass-derived hydrochars laboratory insights. Sci Rep 15, 22176 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07240-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07240-x