Abstract

We aimed to compare the effect of a 10-min walk immediately after glucose ingestion (10-min walk condition) on glycemic control to that of a 30-min walk, 30 min postingestion (30-min walk condition). In a randomized, crossover, counterbalanced trial with three (control, 10-min walk, 30-min walk) conditions, twelve healthy young adults (6 females) walked at a comfortable speed during the walking conditions (control condition = rest) after glucose ingestion (75 g). The walking conditions yielded significantly lower 2-hour glucose areas under the curve (10-min walk = 15607 ± 702, 30-min walk = 15732 ± 731, control = 16605 ± 745 mg·min/dL) and mean blood glucose levels (10-min walk = 127.9 ± 19.4, 30-min walk = 128.9 ± 5, control = 135.8 ± 20.5 mg/dL) than did the control condition (p < 0.05, d = 0.712-0.898). The 10-min walk condition (164.3 ± 8.9 mg/dL) resulted in a significantly lower peak glucose level than the control condition did (181.9 ± 8.4 mg/dL, p = 0.028, d = 0.731) despite no significant difference between the 30-min walk (175.8 ± 9.6 mg/dL) and control (p = 0.184, d = 0.410) conditions. A brief 10-min walk immediately after a meal appears to be an effective and feasible approach for the management of hyperglycemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Postprandial hyperglycemia is associated with various conditions, such as cardiovascular diseases and dementia1,2,3. Sustained postprandial hyperglycemia is considered a major factor in the elevation of HbA1c levels, which increases the risk of cardiovascular-related mortality regardless of diabetes status4. The increase in oxidative stress associated with postprandial hyperglycemia is suggested to be a major factor in the impairment of endothelial and cognitive functions5. Thus, meal-to-meal blood glucose control is crucial for the prevention of various diseases.

Exercise has been identified as an effective method to suppress the rise in blood glucose levels after meals. For example, exercise 30 min after a meal is considered optimal for blood glucose control6. According to the exercise prescription guidelines proposed by the American College of Sports Medicine, engaging in moderate-intensity exercise for at least 30 min per day, five days a week, totaling 150 to 300 min per week, is recommended for maintaining and improving health7. Similar levels of physical activity are also advocated for diabetes prevention8. However, the rate of exercise implementation is a challenge worldwide9,10. Additionally, individuals who find it difficult to engage in prolonged exercise, such as pregnant women, face challenges in meeting the recommended levels of physical activity11, with cases of gestational diabetes being reported12. Furthermore, the subjective perception of effort during exercise can be a barrier to exercise adherence13. Therefore, in the context of postprandial blood glucose control, exercise prescriptions that are easily accessible and can be implemented by various populations are needed.

In this context, a previous study suggested that even a 10-min walk 30 min after dinner is as effective as a 30-min walk, 30 min after dinner for postprandial blood glucose control, with a lower tendency toward blood glucose elevation in both walking conditions than in the resting condition14. Interestingly, a previous study reported a better effect of a 30-min walk immediately after meals15 than a 30-min walk, 30 min after a meal, the latter of which is generally recommended for blood glucose control6. Given the impact of walking immediately after meals on postprandial blood glucose control15, even a 10-min walk, if it is conducted immediately after a meal, could be a more effective and feasible strategy to suppress the rise in blood glucose levels than the previously recommended substantial amount of walking (e.g., 30-min walk).

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess the impact of a 10-min walk immediately after glucose ingestion (i.e., 10-min walk condition) on blood glucose control compared with that of a 30-min walk 30 min after glucose ingestion (i.e., 30-min walk condition). Given the effectiveness of exercise immediately after meals for blood glucose control, we hypothesized that 10 min of light exercise immediately after glucose ingestion would contribute to better blood glucose control than 30 min of walking late after glucose ingestion.

Methods

Experimental design and participants

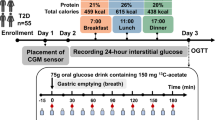

Twelve healthy young adults (Table 1) participated in a randomized, crossover, counterbalanced trial. Participants were excluded from this study if they reported (a) smoking within the past year, (b) having a mental disorder or cardiovascular disease, or (c) having diabetes mellitus or glucose intolerance. The study included three conditions: a control condition, a 10-min walk condition, and a 30-min walk condition. In the 10-min walk condition, participants engaged in a 10-min treadmill walk immediately after the glucose load. In the 30-min walk condition, the participants remained seated in a controlling state for 30 min after the glucose load, followed by a 30-min treadmill walk. In the control condition, the participants maintained a seated controlled position. The walking speed was self-selected by the participants to be comfortable15. The participants were instructed to walk at their usual relaxed pace as in their daily life. The walking speed was set on a treadmill and was implemented at the same speed for the two walking conditions. The ingestion of 75 g of oral glucose was used as a glucose tolerance test (OGTT: 75 g of Trelan G liquid; Yoshindo Inc., Ltd., Tokyo. Japan). This study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Experiments at Ritsumeikan University (BKC-LSMH-2023-101). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All the experiments were performed in the laboratory at 22–24 °C.

Experimental procedures and measurement

This experiment was conducted according to the procedures shown in Fig. 1. The participants visited the laboratory four times (one for informed consent and three for the actual experiment). On the day of their first experimental visit, randomly assigned participants visited the laboratory for measurements of height, weight, body composition, resting systolic BP, and resting diastolic BP. Weight and body composition were measured using a body scale (WB-510; Tanita Co., Tokyo, Japan). Resting systolic BP and resting diastolic BP were measured using a blood pressure monitor (HEM-7126; Omron Co., Kyoto, Japan). The participants adjusted their speed themselves to determine the walking speed. All conditions started at 8:00 AM, and the participants remained seated quietly for 20 min. Next, baseline measurements of blood glucose levels and heart rate were taken while the participants were seated at rest. After completion of the remaining measurements, the participants ingested 75 g of a solution containing glucose precisely over 1 min. Heart rate, gastrointestinal discomfort and the rating of perceived exertion (RPE) score were measured after completion of the exercises. Heart rate was measured using an HR monitor (Polar Vantage M; Polar Electro Co., Kempele, Finland).

Blood glucose levels

In all trials, fingertip punctures were performed every 10 min from glucose intake until 120 min afterward to measure blood glucose levels. Blood glucose levels were measured using a glucose meter (Glucocard G Black; ARKRAY, Inc., Kyoto, Japan). In this study, on the basis of international consensus, the 2-hour postprandial areas under the blood concentration‒time curve (AUCs) for blood glucose levels and mean blood glucose levels were calculated16.

Objective rating scales

Considering the feasibility of the walking protocol used in this study, measurements were taken to indicate the psychological barriers to walking. Subjective exercise intensity at the end of exercise was assessed using the Borg 6–20 scale17, which is a 15-point scale ranging from 6 (very light) to 20 (very hard).

There are concerns about the burden on the digestive system when walking immediately after glucose intake. Therefore, gastrointestinal discomfort was measured to clarify the impact on the digestive system. Gastrointestinal sensations were assessed using a visual analog scale (VAS; 100 mm), where subjects marked the level on a 100 mm line from ‘none at all (0 mm)’ on the left end to ‘very much (100 mm)’ on the right end, corresponding intuitively to their current feelings.

Statistics

For normally distributed data, values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). For nonnormally distributed data, medians and interquartile ranges are provided. Blood glucose AUC, mean blood glucose, and peak blood glucose values were compared among conditions using one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). A Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) post hoc test was subsequently conducted to compare differences between groups. A paired t test was conducted to investigate whether there were any specific differences between the conditions. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare the RPE between walking conditions. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to analyze the interaction effects of condition and time on heart rate at baseline and postwalking. Specific differences were identified using a paired t test as a post hoc test. Cohen’s d effect size (ES) was calculated using the pooled SD to assess the magnitude of differences in the measured variables between conditions. The Cohen’s d ES was interpreted as follows: small (0.20 ≤ d < 0.50), medium (0.50 ≤ d < 0.80), and large (d ≥ 0.80), whereas the r ES was interpreted as small (0.10 ≤ r < 0.30), medium (0.30 ≤ r < 0.50), and large (0.50 ≤ r)18. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were primarily conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software ver. 29 (International Business Machines Co., Armonk, NY, United States). Specific analyses, such as the calculation of the r ES derived from the Wilcoxon test and its 95% confidence intervals using bootstrapping, were performed using RStudio ver. 2025.05.0 Build 496 (Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA, United States).

Results

Blood glucose AUC

The results revealed a significant main effect of condition on the 2-hour blood glucose (Fig. 2) AUC (p = 0.035, ηp2 = 0.263). Post hoc comparisons revealed that the blood glucose AUC over the specified period was significantly lower in the 10-min walk condition (15607 ± 702 mg·min/dL) than in the control condition (16605 ± 745 mg·min/dL, p = 0.011, d = 0.876 [95% CI 0.191 to 1.533]; Fig. 3A). Additionally, the blood glucose AUC was significantly lower in the 30-min walk condition (15732 ± 731 mg·min/dL) than in the control condition (p = 0.030, d = 0.716 [95% CI 0.065 to 1.342]; Fig. 3A). There was no significant difference in the blood glucose AUC between the 10-min walk condition and the 30-min walk condition (p = 0.795, d = − 0.077 [95% CI − 0.642 to 0.491]).

Blood glucose levels. (A) The area under the curve (AUC) of blood glucose levels measured over a two-hour period following glucose intake. The 10-min walk and 30-min walk conditions significantly differed from the control conditions (*p < 0.05). The values are presented as the means ± SDs. (B) The average blood glucose level measured over a two-hour period following glucose intake. The 10-min walk and 30-min walk conditions significantly differed from the control conditions (*p < 0.05). The values are presented as the means ± SDs. (C) The peak blood glucose level reached during the two-hour period following glucose intake. The 10-min walk condition was significantly different from the control condition (*p < 0.05). The values are presented as the means ± SDs.

Mean blood glucose levels

There was a significant main effect of condition on the mean blood glucose level (p = 0.034, ηp2 = 0.265). Post hoc comparisons revealed that the mean blood glucose levels were significantly lower in the 10-min walk condition (127.9 ± 19.4 mg/dL) than in the control condition (135.8 ± 20.5 mg/dL, p = .010, d = 0.898 [95% CI 0.207 to 1.560]; Fig. 3B). Additionally, the mean blood glucose levels were significantly lower in the 30-min walk condition (128.9 ± 5.8 mg/dL) than in the control condition (p = .031, d = 0.712 [95% CI 0.062 to 1.337]; Fig. 3B). There was no significant difference in the mean blood glucose levels between the 10-min walk condition and the 30-min walk condition (p = .781, d = − 0.082 [95% CI − 0.647 to 0.486]).

Peak blood glucose levels

The results revealed that the main effect of the condition on peak blood glucose levels (Fig. 2) was significant (p = 0.044, ηp2 = 0.248). Post hoc comparisons revealed that the peak blood glucose value was significantly lower in the 10-min walk condition (164.3 ± 8.9 mg/dL) than in the control condition (181.9 ± 8.4 mg/dL, p = 0.028, d = 0.731 [95% CI 0.077 to 1.359]; Fig. 3C). There was no significant difference in peak blood glucose levels between the 30-min walk condition (175.8 ± 9.6 mg/dL) and the control condition (p = 0.184, d = 0.410 [95% CI − 0.189 to 0.992]). Additionally, there was no significant difference in peak blood glucose levels between the 10-min walk condition and the 30-min walk condition (p = 0.182, d = − 0.411 [95% CI − 0.993 to 0.188]).

Heart rate and subjective measures

The participants walked at a self-perceived comfortable speed of 3.8 ± 0.2 km/h. The RPE was significantly lower during the 10-min walk condition (7 [6 − 7]; median [IQR], p = 0.003, r = 0.85 [95% CI 0.738 to 0.906]; Fig. 4A) than during the 30-min walk condition (9 [8 − 10]; median [IQR]). Table 2 shows the heart rate values in the control group and during the latter part of the exercise. A significant main effect of time was observed for heart rate (p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.951), but no significant main effects were observed for conditions (p = 0.430, ηp2 = 0.058) or interactions (p = 0.271, ηp2 = 0.109). With respect to gastrointestinal sensations measured via the VAS at the end of exercise (Fig. 4B), there was no significant difference between the 10-min walk condition (0 [0–1] mm) and the 30-min walk condition (1.5 [0–2.25] mm, p = 0.203, r = 0.37 [95% CI − 0.321 to 0.762]).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of 10 min of walking immediately after glucose ingestion on blood glucose control compared with 30 min of walking. Both the AUC of blood glucose levels within 2 h after glucose intake and the mean blood glucose levels were significantly lower in the 10-min walk condition than in the 30-min walk condition or the control condition. Additionally, the peak blood glucose level was significantly lower in the 10-min walk condition than in the control condition. Conversely, there was no difference in the peak blood glucose level between the 30-min walk condition and the control condition. Given these findings, the 10-min walk condition may be a practical and effective option for controlling postprandial blood glucose levels compared with the recommended 30-min walk condition.

Postprandial hyperglycemia contributes to the risk of developing cardiovascular disease5 and an increase in HbA1c, regardless of the presence of diabetes4. A previous study investigating the effects of exercise timing (i.e., 30 min of exercise before a meal, immediately after a meal, or 30 min after a meal) on postprandial glycemic responses revealed that exercising immediately after a meal is the most effective for attenuating blood glucose elevations and suggested that the timing of exercise is an important factor for blood glucose control15. We found that, regarding the blood glucose AUC and mean blood glucose levels, both the 10-min walk condition and the 30-min walk condition yielded significantly lower values than did the control condition. On the other hand, a previous study revealed that longer durations of walking (i.e., 40-min walk) resulted in a lower 2-hour postprandial blood glucose AUC than a 15-min walk if the timing of exercise was the same19. These findings highlight that not only exercise volume and/or duration but also the timing of exercise plays a crucial role in postprandial glycemic control.

Interestingly, compared with the control condition, the 10-min walk condition significantly suppressed the peak blood glucose levels. Conversely, no significant difference in peak values was observed between the previously recommended 30-min conditions and the control conditions. This lack of effect may be attributable to exercise not being initiated immediately after glucose ingestion in the 30-min condition, thus allowing postprandial glucose excursion to occur. Postprandial blood glucose levels typically peak within 30 to 60 min after glucose ingestion20. A meta-analysis of nondiabetic patients suggested that the risk of developing cardiovascular disease is related to peak blood glucose levels21. Overall, walking immediately after a meal, even for a short period of time, could be effective in preventing diseases without the previously recommended amount of walking after some rest following the meal.

While postprandial exercise clearly contributes to effective blood glucose control, its effects might not last for blood glucose control during subsequent meals22,23. It is necessary to engage in exercise after every meal to suppress the rapid rise in blood glucose levels associated with eating. Previous research has reported that walking for 30 min is effective in suppressing the rise in blood glucose levels after meals6,15. However, in the current context of low exercise rates and a busy modern society, ensuring 30 min of exercise after every meal is not practical. Conversely, the 10-min walk immediately after meals utilized in this study could become a widely applicable strategy to effectively suppress postprandial hyperglycemia. In the 10-min walk condition, the RPE was relatively lower than that in the 30-min walk condition, which ensured that the exercise was considered light from a subjective perspective. Moreover, gastrointestinal discomfort values were low and comparable to those observed with the previously recommended method of walking, which suggested that concerns regarding the impact of starting exercise immediately after glucose intake on the digestive system might be negligible. Therefore, these findings imply that brief bouts of physical activity may serve as a time-efficient and feasible alternative to prolonged exercise sessions, particularly for people who struggle to find time to exercise.

One might be concerned about whether the same effects observed in this study would be achieved when this exercise is applied to elderly individuals, obese individuals, patients with metabolic disorders, or pregnant women. These groups might experience a lower exercise intensity than healthy young participants when walking at a comfortable pace. However, a previous study targeting women over 50 years old reported that an even slower 15-min walk, with a similar relative intensity in terms of participants’ heart rate to that in the present study, can effectively suppress the postprandial increase in blood glucose levels19. It is possible that performing short walks immediately after a meal, even in elderly individuals or pregnant women, may significantly benefit blood glucose control.

In Japan, considering the physical activity levels of the population, increasing physical activity (PA) even by as little as 10 min is recommended on the basis of a meta-analysis of 26 cohort studies showing that increasing PA by just 10 min per day can lead to a 3.2% reduction in the average relative risk of noncommunicable diseases, dementia, musculoskeletal impairments, and mortality24. The “Active Guide”, i.e., the Japanese official physical activity guidelines for health promotion established in 2013, includes the “Plus Ten” message, which encourages individuals to increase their PA by an additional 10 min compared with their current activity levels25. In this context, the findings of this study could serve as new evidence for the “Plus Ten” campaign by considering the timing of implementation (i.e., performing a 10-min walk immediately after a meal).

In this study, several limitations can be identified. We should acknowledge that the participants in the present study were young, healthy adults, which restricts the generalizability of the findings to other populations (e.g., individuals with diabetes4, older adults26, or pregnant women27), although we have already postulated that a 10-min walk immediately after a meal may be effective even in such populations. Given the potential differences in glucose metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and physical activity responses in these populations, however, future studies should specifically target these groups to evaluate whether similar effects can be observed under conditions tailored to their physiological characteristics. Additionally, the mechanisms underlying the suppression of blood glucose elevation observed in this study remain unclear, and clear mechanisms have not been identified, as described in a previous study15. Glucose uptake is promoted by insulin-independent glucose uptake through the contraction of skeletal muscles during walking, among other various transcription processes that are intricately involved28. Further research is needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying the effects of light exercise initiated immediately after meals. Furthermore, the 75 g OGTT used in the present study may not adequately reflect physiological postprandial glycemic responses compared with real meals, which typically include macronutrients (i.e., fat, protein, and dietary fiber). These components influence gastric emptying and glucose absorption, potentially resulting in a blunted rise in postprandial blood glucose levels. For example, coingestion of protein with glucose can attenuate postprandial glycemic excursions29. Additionally, dietary fat has been reported to delay gastric emptying and shift the timing of blood glucose elevation30. Despite these modulatory effects of meal composition, recent evidence has demonstrated that initiating exercise immediately after a meal is more effective in attenuating postprandial glycemic responses than exercising 30 min after consumption, even when mixed liquid meals containing glucose, fats, and proteins are used15. This suggests that the 10-min walk immediately after glucose ingestion used in the present study may also be effective when applied to meals typically consumed in everyday life. Nevertheless, to further improve the practical applicability of these findings, future studies should be conducted using mixed meals that reflect commonly consumed meals.

Conclusion

Even a brief walk immediately after a meal was suggested to be effective for suppressing postprandial blood glucose elevation, with effects similar to those of a 30-min walk. Given its simplicity and lower time burden, a 10-min walk is more feasible for incorporation into daily life. Thus, such a regimen of walking for 10 min after meals could become a widely applicable and effective exercise style for blood glucose control. The results obtained from this study provide important insights prescribing exercise to suppress excessive increases in postprandial blood glucose levels in modern society, where securing time for exercise is challenging.

Data availability

The date supporting the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Alfieri, V. et al. The role of glycemic variability in cardiovascular disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 8393. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22168393 (2021).

Ding, Y. et al. Metformin in cardiovascular diabetology: A focused review of its impact on endothelial function. Theranostics 11, 9376–9396. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.57690 (2021).

Zuo, W. & Wu, J. The interaction and pathogenesis between cognitive impairment and common cardiovascular diseases in the elderly. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 13, 20406223211063020. https://doi.org/10.1177/20406223211063020 (2022).

Monnier, L., Lapinski, H. & Colette, C. Contributions of fasting and postprandial plasma glucose increments to the overall diurnal hyperglycemia of type 2 diabetic patients: Variations with increasing levels of HbA1c. Diabetes Care. 26, 881–885. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.26.3.881 (2003).

Blaak, E. E. et al. Impact of postprandial glycaemia on health and prevention of disease. Obes. Rev. 13, 923–984. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01011.x (2012).

Chacko, E. Exercising tactically for taming postmeal glucose surges. Scientifica 2016, 4045717. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/4045717 (2016).

Garber, C. E. et al. American college of sports medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: Guidance for prescribing exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 43, 1334–1359. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318213fefb (2011).

Kanaley, J. A. et al. Exercise/physical activity in individuals with type 2 diabetes: A consensus statement from the American college of sports medicine. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 54, 353–368. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000002829 (2022).

Guthold, R., Stevens, G. A., Riley, L. M. & Bull, F. C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. 6, e1077–e1086. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30357-7 (2018).

Miles, L. Physical activity and health. Nutr. Bull. 32, 314–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-3010.2007.00668.x (2007).

Di Fabio, D. R., Blomme, C. K., Smith, K. M., Welk, G. J. & Campbell, C. G. Adherence to physical activity guidelines in mid-pregnancy does not reduce sedentary time: An observational study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 12, 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-015-0188-3 (2015).

Ovesen, P. G. et al. Temporal trends in gestational diabetes prevalence, treatment, and outcomes at Aarhus university hospital, skejby, between 2004 and 2016. J. Diabetes Res. 2018 5937059. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/5937059 (2018).

Trost, S. G., Owen, N., Bauman, A. E., Sallis, J. F. & Brown, W. Correlates of adults’ participation in physical activity: Review and update. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 34, 1996–2001. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-200212000-00020 (2002).

Shambrook, P. et al. A comparison of acute glycaemic responses to accumulated or single bout walking exercise in apparently healthy, insufficiently active adults. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 23, 902–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2020.02.012 (2020).

Solomon, T. P. J. et al. Immediate post-breakfast physical activity improves interstitial postprandial glycemia: A comparison of different activity-meal timings. Pflugers Arch. 472, 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-020-02380-0 (2020).

Danne, T. et al. International consensus on use of continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Care 40, 1631–1640. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc17-1600 (2017).

Borg, G. A. V. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 14, 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1249/00005768-198205000-00012 (1982).

Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 112, 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155 (1992).

Nygaard, H., Tomten, S. E. & Høstmark, A. T. Slow postmeal walking reduces postprandial glycemia in middle-aged women. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 34, 1087–1092. https://doi.org/10.1139/H09-109 (2009).

Jarvis, P. R. E., Cardin, J. L., Nisevich-Bede, P. M. & McCarter, J. P. Continuous glucose monitoring in a healthy population: Understanding the post-prandial glycemic response in individuals without diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 146, 155640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2023.155640 (2023).

Hulman, A. et al. Heterogeneity in glucose response curves during an oral glucose tolerance test and associated cardiometabolic risk. Endocrine 55, 427–434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-016-1222-7 (2017).

Derave, W., Mertens, A., Muls, E., Pardaens, K. & Hespel, P. Effects of post-absorptive and postprandial exercise on glucoregulation in metabolic syndrome. Obesity 15, 704–711. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.590 (2007).

Larsen, J. J., Dela, F., Kjær, M. & Galbo, H. The effect of moderate exercise on postprandial glucose homeostasis in NIDDM patients. Diabetologia 40, 447–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001250050694 (1997).

Miyachi, M., Tripette, J., Kawakami, R. & Murakami, H. +10 min of physical activity per day: Japan is looking for efficient but feasible recommendations for its population. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 61, S7–S9. https://doi.org/10.3177/jnsv.61.S7 (2015).

Ministry of Health. Labour and Welfare, Japan. Active Guide –Japanese official physical activity guidelines for health promotion. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. (2013). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/houdou/2r9852000002xple.html.

Curl, C. C. et al. Altered glucose kinetics occurs with aging: A new outlook on metabolic flexibility. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 327, E217–E228. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.00091.2024 (2024).

Thaweethai, T., Soetan, Z., James, K., Florez, J. C. & Powe, C. E. Distinct insulin physiology trajectories in euglycemic pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 46, 2137–2146. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-2226 (2023).

Almuraikhy, S., Doudin, A., Domling, A., Althani, A. A. J. F. & Elrayess, M. A. Molecular regulators of exercise-mediated insulin sensitivity in non-obese individuals. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 28, e18015. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.18245 (2024).

Gentilcore, D. et al. Effects of fat on gastric emptying of and the glycemic, insulin, and incretin responses to a carbohydrate meal in type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91, 2062–2067. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2005-2644 (2006).

Gannon, M. C. & Nuttall, F. Q. Control of blood glucose in type 2 diabetes without weight loss by modification of diet composition. Nutr. Metab. (Lond.) 3, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-3-16 (2006).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the time and effort expended by the volunteer participants. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. The results of the study are presented clearly, honestly, and without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation. The results of the present study do not constitute endorsement by the American College of Sports Medicine.

Funding

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (to T. H.), grant number # 23K21635.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.H. conceived and designed research; K.H., K.D., Y.M., T.M., and Y.S. performed the experiments; K.H. analyzed data; K.H. and T.H. interpreted data; K.H. prepared figures and drafted the manuscript; K.H., K.D., Y.M., T.M., I.W.Y. and T.H. edited and revised the manuscript; All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hashimoto, K., Dora, K., Murakami, Y. et al. Positive impact of a 10-min walk immediately after glucose intake on postprandial glucose levels. Sci Rep 15, 22662 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07312-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07312-y