Abstract

Defocus blur commonly arises from the cameras’ depth-of-field limitations. While the deep learning method shows promise for image restoration problems, defocus deblurring requires accurate training data comprising pairs of all-in-focus and defocus images, which can be difficult to collect in real-world scenarios. To address this problem, we propose a high-resolution iterative deblurring method for real scenes driven by a score-based diffusion model. The method trains a score network by learning the score function of focused images at different noise levels and reconstructs high-quality images through reverse-time stochastic differential equation (SDE). A prediction-correction (PC) framework corrects discretization errors in the reverse-time SDE to enhance the robustness of images during reconstruction. The iterative nature of diffusion models enables a gradual improvement in image quality by progressively enhancing details and refining marginal distribution with each iteration. This process allows the distribution of generated images to increasingly approximate that of sharply focused images. Unlike mainstream end-to-end approaches, this method does not require paired all-in-focus and defocus images to train the model. The real-world datasets, such as self-captured datasets, were used for model training. Additional testing was conducted on the RealBlur and DED datasets to evaluate the efficacy of the proposed method. Compared to DnCNN, FFDNet and CycleGAN, superior performance was achieved by the proposed method on real-world datasets, including self-captured scenarios, with experimental results showing improvements of approximately 13.4% in PSNR and 34.7% in SSIM. These results indicate that significant enhancement in the clarity of defocus images can be attained, effectively enabling high-resolution iterative defocus deblurring in real-world scenarios through the diffusion model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Defocus images result from the inherent limitations of the cameras’ depth-of-field during the capture process1. This defocusing phenomenon is prevalent in various typical scenarios, such as fast-paced photography, motion tracking, and remote monitoring. It can result in diminished image quality, loss of detail, and challenges in subsequent image processing tasks like semantic segmentation2,3 and object detection4,5. Traditional methods for solving the issue primarily involve filtering techniques like the Laplacian filter6, wavelet transform7, and reciprocal filtering8. Significant advancements have been made in enhancing these conventional methodologies. For instance, Mueller et al.9 developed an effective image interpolation framework based on wavelet-based linear interpolation. The framework restores spatial resolution and details by combining multi-scale analysis with geometric representation. Similarly, Lim et al.10 refined the Wiener filter restoration by incorporating a window function to minimize boundary artifacts and distortions, thereby improving the precision and quality of image restoration. Zheng et al.11 optimized the constrained least squares filter restoration method by employing an incremental constrained least squares filter to reduce the defocus blur in two-dimensional barcodes. Despite these advancements, filter-based methods often suffer from drawbacks such as information loss, inaccuracies in blur estimation, and suboptimal performance on severely defocused images12. Furthermore, traditional defocus image processing methods lack robustness and necessitate manual parameter adjustments, thereby demanding a high degree of operator proficiency13.

To overcome the limitations of filter-based techniques, several more efficient, precise, and robust alternatives have been put forward for the processing of defocus images, such as non-blind deconvolution. The techniques involve estimating the blur kernel to achieve a high-quality image through deconvolution. For instance, Nisha et al.14 introduced a rapid deblurring method for infrared images and an analytical modeling approach for blur kernels. By combining accurate blur kernel estimation with the non-blind deconvolution technique, this method has enhanced the quality and real-time efficiency of the deblurring process. Goldstein et al.15 developed a novel method based on power spectrum statistical anomalies to extract motion blur kernels from blurred images. By directly estimating the power spectrum of the blur kernel from the input images and utilizing an enhanced phase recovery algorithm, the technique not only enhanced result accuracy but also reduced computational time. Pan et al.16 introduced a method that includes a L0-regularized prior and combines intensity and gradient data, in addition to employing a half-quadratic splitting optimization approach. This strategy produces reliable intermediate results for the estimation of blur kernel, leading to improved accuracy in the estimation of blur kernel and clearer image restoration. Nevertheless, the techniques employed to enhance blurred images by estimating blur kernels frequently oversimplify the real instances of blur and restrict defocus blur to particular forms17. As a result, they were less efficient under severe blurring scenarios.

In recent years, deep learning methods18,19,20,21 have been extensively utilized in the field of image processing, demonstrating significant potential in the application of defocus deblurring. For example, Nazir et al.18 proposed a new method that uses deep convolutional neural networks (DNNs) to simultaneously perform depth estimation and image restoration from defocus images. The framework combines depth estimation with image deblurring, effectively training the model using a defocus image dataset. The results demonstrated significant improvement in both depth estimation accuracy and image restoration, showcasing the powerful capabilities of deep learning in handling complex image restoration tasks. Zha et al.19 introduced a method for image restoration that utilizes a triple complementary prior. This method effectively utilizes non-local self-similarity (NSS) priors from both internal and external sources, enabling robust restoration without the need for extensive supervised training. By incorporating these priors, this method improves the quality of the restored images. Experimental results indicated that this method outperforms traditional image restoration techniques. Furthermore, Zha et al.20 explored the effectiveness of simultaneously using NSS priors from both degraded images and an external clear image corpus. The method focuses on clustering similar image patches to form groups that enhance the restoration process.This proposed model demonstrated higher performance in recovering details and reducing artifacts, particularly in challenging scenes like severe blur. The results highlighted the potential of introducing external NSS priors in image restoration tasks, leading to higher quality output. Zamir et al.22 proposed a multi-stage progressive image restoration method (MPRNet), which employs a U-Net network to iteratively optimize image quality by enhancing details in sequential stages. Cho et al.23 used a network with deep generative priors and a U-Net network for image blind deconvolution (MIMO-UNet). This network combines the deep generative model with the robust image restoration capability of the U-Net network, effectively restoring the original image even in the absence of specific blur information. Zhang et al.24 proposed a network (DBGAN) based on employing generative adversarial networks (GANs) for image deblurring. This method can better fit the blurring effect in the actual photography process by simulating the real blurring process to train GAN, leading to more precise image restoration. Furthermore, Tao et al.25 introduced a scale-recurrent network (SRN) for deep image deblurring. This network repeatedly utilizes the same network structure at different scales to achieve multi-scale processing of images, effectively restoring image details from coarse to fine. While the U-Net network demonstrates efficiency in denoising and imaging tasks, it relies on substantial quantities of labeled data for training, which can be challenging to obtain. For GAN, controlling synchronization between two adversarial networks within its framework is difficult and may lead to unstable training processes26. Moreover, SRN may not perform well when handling images with significant scale variations.

Considering the limitations of the above networks, score-based diffusion models27 have gained attention for their distinct advantages and have demonstrated notable performance and benefits in the domain of image processing. Diffusion models generate new data samples by learning the underlying distribution of data27. This means that they can provide strong support for learning strategies that rely on large unlabeled datasets, such as unsupervised28 and semi-supervised29 learning approaches. Therefore, these models can show great practical value and significant advantages in the case of limited labelled data30. This study proposes a novel high-resolution iterative defocus deblurring method for real scenes driven by score-based diffusion model, aiming to improve the clarity and enrich the informational content of defocus images. The method enhances the clarity and informational content of images by reconstructing defocus images through the acquisition of their probability distribution. Specifically, this method entails training data samples using specified imaging parameters and model, constructing a score network, and acquiring knowledge about the probability distribution of images. Ultimately, defocus images are reconstructed using reverse-time stochastic differential equation (SDE) to generate high-quality images31. The essence of the method is to learn a probability distribution and utilize it as a foundation for reconstructing defocus images. A major advantage is the model’s ability to extract consistent features even amid data ambiguities, utilizing prior knowledge to improve reconstruction quality. This model not only captures the intrinsic features of images but also has powerful generalization capability, effectively enhancing images in scenarios with limited labeled data. In contrast to conventional defocus image processing techniques, the defocus deblurring method grounded in score-based diffusion models provides superior precision and efficiency. The iterative nature of diffusion models enables a gradual improvement in image quality by progressively enhancing details and refining marginal distribution with each iteration. This process allows the distribution of generated images to increasingly approximate that of sharply focused images. Unlike mainstream end-to-end approaches, this method does not require paired all-in-focus and defocus images to train the model, which simplifies the process of dataset construction. The real-world datasets, such as self-captured datasets, were used for model training. Additional testing was conducted on the RealBlur and DED datasets to evaluate the efficacy of the proposed method. Compared to DnCNN, FFDNet, and CycleGAN, superior performance was achieved by the proposed method on real-world datasets, including self-captured scenarios, with experimental results showing improvements of approximately 13.4% in PSNR and 34.7% in SSIM. These results indicate that significant enhancement in the clarity of defocus images can be attained, effectively enabling iterative defocus deblurring in real-world scenarios through the diffusion model.

Experimental results

The test dataset comprises real-world photos captured by our team on the campus of Nanchang University, DPDD dataset, DED dataset and RealBlur dataset. By importing the test images into the reconstruction part of the program, defocus deblurred images were obtained. Figures 1(a)−1(g) show the iterative process of image deblurring on defocus images driven by the score-based diffusion model. Figures 1(h)−1(n) and 1(o)−1(u) show the iterative process of two specific areas zoomed in from Fig. 1(g). Figures 1(v) and 1(w) show the variations in PSNR and SSIM during the image iteration process, respectively. The images started iterating from noisy versions, with the main features of the image subject beginning to emerge after 300 iterations, and then becoming clearer as the number of iterations increased. The local generation process of the images can also be observed in Figs. 1(h)−1(n) and 1(o)−1(u). At the 350th iteration, local contours of the image started to appear, and as the number of iterations increased, details such as the lines and contours of leaves and floor tiles became increasingly clear. By the 700th iteration, the image was essentially reconstructed using the proposed method, and the quality of the image was further improved. The graphical representations of PSNR and SSIM iterations indicate that during the initial 0 to 300 iterations, the PSNR metric exhibited a stable trend, while there was a slight rise in the SSIM values. However, after about 300 iterations, the values of both PSNR and SSIM began to rise rapidly. By the 700th iteration, the PSNR value had reached 24.79 dB and the SSIM value had risen to 0.83. Subsequently, both values exhibited a tendency towards stabilization, with the PSNR approaching 25.08 dB and the SSIM approaching 0.84, as illustrated by the black arrows in Figs. 1(v) and 1(w). By the 900th iteration, the PSNR value had reached its maximum level, and the quality of the image was further enhanced. These results demonstrate that the defocus deblurring method via the score-based diffusion model is capable of effectively enhancing defocus images (more information about the iteration process can be found in Visualization 1).

Figure 2 demonstrates the effect of different methods for deblurring on the self-photographed dataset. In scene 1, Figs. 2(a)−2(f) show the reconstruction results using the proposed method, the FFDNet method32, the DnCNN method33, the CycleGAN method34, the defocus image and the real image, respectively. Figures 2(g)−2(l) follow the same convention in scene 2 and Figs. 2(m)−2(r) in scene 3. Figures 2(s)−2(t) show zoomed-in details of Figs. 2(f), 2(i) and 2(r), respectively. The reconstructed images using the proposed method show sharper details compared to the FFDNet method, DnCNN method and CycleGAN method. For example, leaves, chairs and floor tiles are very similar to the real image. It is clear that the images reconstructed using the proposed method, i.e., Figs. 2(a), 2(g), and 2(m), have much higher clarity and vividness compared to the images reconstructed using the FFDNet method, the images reconstructed using the DnCNN method, the images reconstructed using the CycleGAN method, and the defocus images. This proves the excellent performance of the proposed method. In terms of quantitative analysis, the proposed method achieves a PSNR of 25.08 dB and an SSIM of 0.84 in Fig. 2(a). Compared to the image reconstructed using the FFDNet method in Fig. 2(b), the PSNR and SSIM are improved by 2.41 dB and 0.2, respectively. Compared to the image reconstructed using the DnCNN method in Fig. 2(c), the PSNR and SSIM are improved by 2.79 dB and 0.23. Compared with the image reconstructed using the CycleGAN method in Fig. 2(d), the PSNR and SSIM improved by 2.24 dB and 0.13 compared with the corresponding defocus image in Fig. 2(e), they improved by 0.9 dB and 0.06, respectively. for Fig. 2(g), the proposed method achieves 25.75 dB of PSNR and 0.85 SSIM. Compared to the image reconstructed using the FFDNet method in Fig. 2(h), the PSNR and SSIM are improved by 3.57 dB and 0.17, respectively. Compared to the image reconstructed using the DnCNN method in Fig. 2(i), the PSNR and SSIM are improved by 3.46 dB and 0.16, respectively. Compared to the image reconstructed using the CycleGAN method in Fig. 2(j), the PSNR is improved by 0.9 dB and 0.06, respectively. The PSNR and SSIM are improved by 3.25 dB and 0.12, respectively. they are improved by 2.03 dB and 0.08, respectively, compared with the corresponding defocus image in Fig. 2(k). for scene 3, the PSNR and SSIM of the image reconstructed using the proposed method in Fig. 2(m) are 25.37 dB and 0.85, respectively. the PSNR and SSIM of the image reconstructed using the proposed method in Fig. 2(n) are improved by 3.46 dB and 0.16, respectively. the PSNR and SSIM are improved by 2.03 dB and 0.08, respectively. the PSNR and SSIM are improved by 2.04 dB and 0.08, respectively. The PSNR and SSIM of the image reconstructed using the FFDNet method are 2.89 dB and 0.27 respectively. compared to the image reconstructed using the DnCNN method in Fig. 2(o), they are 3.22 dB and 0.3 respectively. compared to the image reconstructed using the CycleGAN method in Fig. 2(p), the PSNR and SSIM are 2.64 dB and 0.19 respectively. They are improved by 2.09 dB and 0.15 compared to the defocus image in Fig. 2(q).The detailed data further demonstrates the significant advantages of using the proposed method for the defocus image reconstruction task as compared to the FFDNet method, the DnCNN method and the CycleGAN method.

Defocus deblurring results of self-captured images under different models. (a)-(f) are the reconstruction results using the proposed method, the FFDNet method, the DnCNN method, the CycleGAN method, the defocus image and GT, respectively. The same rule applies to (g)-(l) and (m)-(r). (s)-(u) are enlarged images of parts (f), (l), and (r), respectively.Ours, refers to an defocus deblurring method based on a fraction-based diffusion model; FFDNet, refers to a fast and flexible denoising method based on convolutional neural networks; DnCNN, refers to a deep convolutional neural network method for image denoising; CycleGAN, refers to an image reconstruction unsupervised generative model; Input, defocus image; GT, real situation.

For further analysis, Fig. 3 illustrates the error maps of the defocus deblurring results. Figures 3(a)−(f), (g)−(l), and (m)−(r) correspond to the error maps of the respective scenes in Fig. 2, respectively. From these plots, it can be seen that the reconstructed images using the proposed method show fewer obvious errors, are clearer, and are closer to the real situation than the FFDNet method, the DnCNN method, and the CycleGAN method. Figures 3(s) and (t) correspond to the pixel values on the white dashed lines in Figs. 2(t) and 2(u), respectively. From Figs. 3(s) and (t), it can be seen that the pixel value curves corresponding to the proposed method are closer to the pixel value curves of the real situation than those of the FFDNet method, the DnCNN method, and the CycleGAN method, which demonstrates the advantage of the scoring-based diffusion model in defocus deblurring.

Error maps of defocus deblurring results. (a)-(e), (f)-(j), and (k)-(o) correspond to error maps for their respective scenes in Figs. 2. (p) and (q) correspond to the pixel values at the white dashed line in Figs. 2(q) and 2(r), respectively. Ours, indicates the defocus deblurring method based on the score-based diffusion model proposed; FFDNet, indicates the fast and flexible denoising method based on the convolutional neural network adopted; DnCNN, indicates the deep convolutional neural network method for image denoising adopted; Input, defocus images; GT, ground truth.

Figure 4 shows the image reconstruction results for different datasets with different methods. Figures 4(a1)−(a6) show the reconstruction results using the proposed method, the reconstruction results of the FFDNet method, the DnCNN method, the CycleGAN method, the defocus image and the real image, respectively. The same conventions apply to Figs. 4(b1)−(b6), (c1)−(c6), and (d1)−(d6). Figures 4(e)−(h) are enlarged regions of Figs. 4(a6), (b6), (c6) and (d6). From these magnified images, it can be observed in detail that the images processed using the proposed method are clearer and more vivid, and the visual effect is enhanced, thus highlighting the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed defocus deblurring method. Also, the images reconstructed using the proposed method are clearer in details (e.g., stone steps, leaves, bicycle seats, and text) compared to the images reconstructed using the FFDNet method, the images reconstructed using the DnCNN method, the images reconstructed using the CycleGAN method, and the defocus images. This demonstrates the superiority of the score-based diffusion model in dealing with defocus blurring. The quantitative analysis results show that for the images in the RealBlur dataset, the reconstructed image using the proposed method in Fig. 4(a1) achieves a PSNR of 28.92 dB and an SSIM of 0.88. Compared with the FFDNet method, the PSNR improved by 1.92 dB and the SSIM improved by 0.2. Compared with the DnCNN method, the PSNR improved by 2.23 dB and SSIM improved by 0.23. Compared with CycleGAN method, PSNR improved by 1.24 dB and SSIM improved by 0.16. Compared with the corresponding defocus image, PSNR improved by 0.86 dB and SSIM improved by 0.1. The image data from the DED dataset shows that the reconstructed image using the proposed method in Fig. 4(b1) PSNR is 29.23 dB and SSIM is 0.92. Compared to FFDNet method, PSNR is improved by 4.4 dB and SSIM is improved by 0.26. Compared to DnCNN method, PSNR of the proposed method is improved by 4.86 dB and SSIM is improved by 0.29. Compared to CycleGAN method, PSNR is improved by 3.66 dB and SSIM improved by 0.14. Compared with the corresponding defocus image, PSNR improved by 1.62 dB and SSIM improved by 0.07. The image data from the DPDD dataset shows that the image reconstructed using the proposed method in Fig. 4(c1) has a PSNR of 28.25 dB and an SSIM of 0.9. Compared with the FFDNet method, PSNR improved by 5.92 dB and SSIM by 0.23. Compared with the DnCNN method, the PSNR improved by 5.19 dB and SSIM by 0.21. Compared with the CycleGAN method, the PSNR improved by 6.02 dB and SSIM by 0.18. Compared with the corresponding defocus image, the PSNR improved by 2.48 dB and SSIM by 0.05. In the self-acquired images, the reconstructed image using the proposed method in Fig. 4(d1) achieves a PSNR of 25.65 dB and an SSIM of 0.88. Compared with the FFDNet method, the PSNR improved by 1.4 dB and the SSIM improved by 0.22. Compared with the DnCNN method, the PSNR improved by 1.84 dB and the SSIM improved by 0.26. Compared with CycleGAN method, PSNR improved by 3.55 dB and SSIM improved by 0.11. Compared with the corresponding defocus images, PSNR improved by 0.49 dB and SSIM improved by 0.12. With the proposed method, the images of these different datasets can be reconstructed efficiently and good results are achieved. This shows that the proposed method can be applied to different experimental environments and has some generalization ability to handle the reconstruction task of defocus images captured by different cameras. These quantitative analysis results provide strong evidence for the effectiveness of score-based diffusion models in supporting defocus deblurring (more information about the iterative process for self-captured images can be found in Visualization 2).

Defocus deblurring results recovered from different datasets using different methods. Figures (a1)-(a6) show the reconstruction results using the proposed method, the FFDNet method, the DnCNN method, the CycleGAN method, the defocus image and the real image (GT). The same convention is applied to Figures (b1)-(b6), (c1)-(c6) and (d1)-(d6). Figures (e)-(h) correspond to zoomed-in images of the boxed regions in Figures (a6), (b6), (c6), and (d6), respectively.Ours denotes the proposed defocus deblurring method based on the diffusion model of scoring; FFDNet denotes the fast and flexible denoising method based on convolutional neural networks; DnCNN denotes the deep convolutional neural network image denoising method employed; CycleGAN denotes the method of image reconstruction using unsupervised generative modeling. The input is an defocus image; GT is a real image.

Conducting tests on defocus images with diverse degrees of defocus blur can not only verify the effectiveness of the proposed method once more but also make it possible to discuss the limitations of the proposed method. Tests were carried out on defocus images captured under different aperture sizes by using this method. The results are shown in Fig. 5. Figures 5(a)−(c) are respectively the results of using the proposed method, defocus image, and ground truth. The same convention also applies to Figs. 5(d)−(f) when the aperture size is set to f/6, Figs. 5(g)−(i) when the aperture size is set to f/4, Figs. 5(j)−(l) when the aperture size is set to f/2, and Figs. 5(m)−(o) when the aperture size is set to f/1. Figures 5(p)−(t) are respectively the local enlarged views of the position within the yellow square frame in Fig. 5(c) under the aperture sizes on their left sides. As the aperture size decreases, the degree of defocus blur increases. Evidently, when the aperture size is relatively large, that is, when the degree of defocus blur is small, the proposed method can better accomplish the defocus deblurring task, making the resulting image clearer and more vivid compared with the test image, which demonstrates the excellent performance of the proposed method. It can be seen from Figs. 5(p)–5(t) that the tile lines and floor tile holes in the images reconstructed by the proposed method are all more clearly visible compared with the defocus images and are more similar to the ground truth. However, when the aperture size is set to f/1, that is, in the case of extreme defocus blur, the image reconstructed by using the proposed method shows little difference from the defocus image. In terms of quantitative analysis, when the aperture size is set to f/8, the degree of defocus blur is the minimum currently. The image reconstructed by using the proposed method and the defocus image are shown in Figs. 5(a)−(b). Compared with the defocus image, the PSNR and SSIM of the image after defocus deblurring increased by 1.75 dB and 0.11, respectively. When the aperture size is set to f/6, the defocus blur becomes more severe. The image reconstructed by the proposed method and the defocus image are shown in Figs. 5(d)–(e). The PSNR and SSIM are only enhanced by 1.61 dB and 0.15, respectively. When the aperture size is set to f/4, the defocus blur intensifies. The image reconstructed by using the proposed method and the defocus image are shown in Figs. 5(g)–(h). The PSNR and SSIM only increased by 0.74 dB and 0.16, respectively. When the aperture size is set to f/2, the defocus blur further intensifies. The image reconstructed by using the proposed method and the defocus image are shown in Figs. 5(j)−(k). The PSNR and SSIM of the image reconstructed by using the proposed method increased by 0.54 dB and 0.12, respectively, and the improvement range decreased again. Finally, in the case of extreme defocus blur, that is, when the aperture size is set to f/1, the image reconstructed by using the proposed method and the defocus image are shown in Figs. 5(m)−(n). The PSNR and SSIM of the image reconstructed by using the proposed method are only 23.91 dB and 0.65, respectively. Only the SSIM of this reconstructed image increased by 0.06 compared with the defocus image. This trend is consistent with the laws of physics: larger apertures lead to shallower depth of field with stronger defocus blur, increased blur kernel size and spatial variability, and more complex iterative model corrections. Despite the fact that the aperture parameters are not explicitly input, the model partially adapts to different blur intensities by empirically learning similar blur patterns from the training data. The experiments under different degrees of defocus blur also further illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed method.

The results of defocus deblurring under different aperture sizes. (a)-(c) are the reconstruction results using the proposed method, defocus images, and GT, respectively. The same convention applies to (d)-(f), (g)-(i), (j)-(l) and (m)-(o). (p)-(t) are respectively the local enlarged views of the position within the yellow square frame in (c) under the aperture sizes on their left sides. Ours, indicates the defocus deblurring method based on the score-based diffusion model proposed; Input, defocus images; GT, ground truth.

Conclusion and discussion

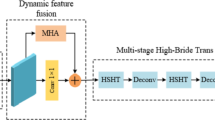

In conclusion, this study proposes an innovative approach for the deblurring of defocus images driven by score-based diffusion model, aiming to overcome limitations observed in existing defocus deblurring methods. The proposed technology involves both forward and reverse SDE processes. In the forward SDE process, zero-mean Gaussian white noise is introduced to perturb the data distribution of sharp images. It is essential to train a score network to estimate the gradient of the logarithm of the data distribution. This enables the effective sampling and capture of the prior distribution of images from the data distribution. Once the score network is trained, the prior knowledge obtained can be used to numerically solve the reverse-time SDE process under the approximate conditions. This reverse process gradually restores clear images from noisy ones, leading to successful defocus deblurring. The self-captured dataset, DPDD, RealBlur, and DED datasets were used to evaluate the performance of the proposed method. In the self-captured dataset, a PSNR of 25.65 dB and an SSIM of 0.88 were achieved using the proposed method. Compared to the FFDNet method, both PSNR and SSIM increased by 1.4 dB and 0.22, respectively. In the DPDD dataset, the PSNR and SSIM achieved by the proposed method were 28.25 dB and 0.9, respectively, showing increases of 5.92 dB and 0.23 compared to the FFDNet method. In the DED dataset, the PSNR and SSIM achieved by the proposed method were 29.23 dB and 0.92, showing increases of 4.4 dB and 0.26 compared to FFDNet method. Finally, in the RealBlur dataset, the PSNR and SSIM were 28.92 dB and 0.88, respectively, with improvements of 1.92 dB and 0.2 over the FFDNet method. These results strongly demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method in the field of defocus deblurring in real-world scenarios.The proposed method achieved high-quality reconstruction of defocus images in real-world scenarios, but there is a limitation in reconstruction speed. As described in Sect. “Dataset acquisition and network parameter introduction”, the method takes 1 s per iteration and requires 700 iterations, resulting in a total reconstruction time of 12 min. Three factors primarily contribute to the lengthy reconstruction process. The diffusion model’s iterative nature is the first factor. The training process of the diffusion model involves training a score network to estimate the unknown score function \(\nabla_{x} \log p_{t} (x_{{\text{t}}} )\). Once the score network \(S_{\theta } (x_{t} ,t)\) is trained using Eq. (7), high-quality reconstruction of defocus images can be achieved by solving the reverse-time SDE using the approximate condition \(S_{\theta } (x_{t} ,t) \simeq \nabla_{x} \log p_{t} (x_{t} )\). The reverse-time SDE process typically requires numerous small-step iterations. Each reverse time step involves solving a differential equation, which generally requires complex mathematical calculations and matrix operations, thus consuming substantial time and computational resources. Secondly, the complexity of the prediction-correction (PC) sampling process contributes to the overall time consumption. As shown in Fig. 7, after training the score network, the reverse-time SDE and annealed Langevin method can be implemented using the approximate condition \(S_{\theta } (x_{t} ,t) \simeq \nabla_{x} \log p_{t} (x_{t} )\). This paper employs the reverse-time SDE as a predictor and refines its results using the annealed Langevin method to correct the marginal distribution, resulting in more accurate and sharper images. Each step in this process requires computing the gradient of the image score, which is particularly time-consuming for high-resolution images. Although this approach enhances image quality, the computational cost per iteration is considerable. Running 1,000 iterations cumulatively results in significantly slower processing. Finally, the slow performance can also be attributed to limitations in computer hardware. The computational capacity of the RTX 2080Ti GPU is becoming inadequate, potentially facing challenges such as memory bandwidth limitations and insufficient parallelism, which negatively affect training and testing times. To shorten the time, the following three strategies can be considered. One is to reduce iteration time. Such as the Come-Closer-Diffuse-Faster (CCDF) method proposed by Chung et al.35, which begin the reverse SDE process from a single forward diffusion state closer to the target distribution rather than from pure Gaussian noise. This modification could dramatically cut down the required sampling steps, thereby reducing the total processing time. In addition to improving initialization, future research could also focus on reducing the number of iterations required during the reverse SDE process. For example, the Image Restoration Stochastic Differential Equation (IR-SDE) method proposed by Luo et al.36, have demonstrated that satisfactory results in 100 iterations by setting the iterative reconstruction to start from a degraded image. Another promising direction involves leveraging more advanced hardware and parallel computing techniques. Upgrading to GPUs with higher memory bandwidth and more processing cores could alleviate the current computational bottlenecks. By incorporating such techniques, it might be possible to strike an optimal balance between computational efficiency and image restoration quality without sacrificing the accuracy and robustness of the reconstructed images.

The generalization ability of the model is also an area that requires improvement. Firstly, the proposed method is primarily designed to address defocus deblurring, and its performance is generally less effective for other types of blur, such as motion blur. In this study, the training dataset comprises the DPDD and self-captured datasets, both specifically targeted for defocus blur. To improve this limitation, we aim to enhance our training dataset to include data representing various types of blur. Secondly, the method was tested in cases of extreme defocus blur, specifically when the aperture size is set to f/1, with results shown in Figs. 5(m)−5(n). The reconstructed image using the proposed method showed only a 0.06 improvement in SSIM compared to the defocus image, indicating limited performance in extreme defocus blur scenarios. This phenomenon is not accidental, but stems from the irreversibility of the physical degradation process. Moreover, method based on score diffusion model in this paper belongs to the data-driven paradigm, whose performance is highly dependent on the reversibility of blur-sharp pairs in the training data, whereas the difficulty of recovery is exacerbated by the insufficient a priori information and the lack of fuzzy kernel diversity in extreme blur scenarios. To address this issue, a broader range of samples reflecting diverse aperture settings and defocus blur levels could be incorporated to better handle extreme defocus blur.

Enhancing model performance is also critically important. One approach to achieve this is by improving the quality of samples generated by diffusion models. For example, Smith et al.37 proposed a framework called SAGDiff (self-attention-guided diffusion model). It can enhance feature extraction by introducing a self-attention mechanism during the diffusion process, thereby improving the quality of generated samples. Integrating self-attention guidance and other optimization techniques within the diffusion model could further elevate image quality and model stability from multiple aspects, which is particularly advantageous for handling complex textures and high-noise environments. Additionally, this study currently relies on a single model to learn prior information. However, the prior knowledge that a single model can capture is inherently limited, whereas multiple models can complement each other in data generation, providing a richer information set. To facilitate handling diverse types of blur, we consider implementing multi-model learning38,39. For instance, Li et al.38 introduced FedDiff, a multimodal collaborative diffusion federated learning framework. This framework employs a dual-branch diffusion model to extract data features, with each model inputting data into separate branches of the encoder. Inspired by this approach, we aim to embed multiple models within the same reconstruction task, leveraging their capabilities to learn prior information from different perspectives. This strategy could enhance the model’s performance and reconstruction quality in addressing various types of blur.

This work combines a score network with SDE to tackle the challenge of defocus images. It not only exhibits theoretical innovation but also shows broad application prospects in practical applications. For instance, it can be applied to high-resolution imaging, surveillance system image enhancement, and medical imaging to improve image quality and diagnostic accuracy. Athough the method currently faces challenges in terms of reconstruction speed and generalization to other types of blur, it has indicated high-resolution iterative defocus deblurring in real-world scenarios through the diffusion model. By reducing iteration time, exploring more efficient training algorithms, diversifying the training data, and exploring multimodal and collaborative frameworks, future work can build upon the foundation laid by this study to develop even more efficient and versatile image restoration systems. With further refinement, the proposed approach holds significant promise for a wide array of practical applications, ultimately leading to enhanced image quality and improved performance in numerous technological domains.

Methods

Langevin dynamics

Langevin dynamics have the capability to produce samples from a probability density \({\text{p}}(x)\) by utilizing the estimated gradient of the log data distribution \(\nabla_{x} \log p_{t} (x_{{\text{t}}} )\)40. It starts from an initial point when \(t = 0\) and iteratively refines it in a noisy gradient ascent manner, thus increasing the value of the log density \(\log p_{t} (x_{{\text{t}}} )\). In many cases, the score function is easier to model and estimate than the original probability density function41. This is especially true for unnormalized density functions, as the score function has the advantage of being independent of the partition function. The iterative estimation of Langevin dynamics is shown in Eq. (1). Throughout the iterative recovery process, the samples at each perturbed noise level serve as the initial input for the subsequent noise level until the minimum level is reached, expanding the samples for the network, and gradually generating the final recovery outcomes.

The process involves a given step size \(\alpha> 0\), standard Gaussian noise \(z\), a total number of iterations \(T\), and initial samples \(x\) from an arbitrary prior distribution \(\pi (x)\). When the step size \(\alpha\) is sufficiently small and the total number of iterations \(T\) is large enough, the distribution of the samples will approach the target probability density function under specific regularity conditions42. Under this circumstance, it is assumed that there is a neural network \(S_{\theta } (x_{t} ,t)\) parameterized by \(\theta\), known as the score network \(S_{\theta } (x_{t} ,t)\), which has been trained to estimate the gradient of the log probability density function:

By substituting \(\nabla_{x} \log p_{t} (x_{{\text{t}}} )\) in Eq. (1) with \(S_{\theta } (x_{t} ,t)\), samples can be approximately generated from \(p(x)\) using annealed Langevin dynamics.

Score-based diffusion model

The diffusion model aims to learn from randomly sampled i.i.d. (independently and identically distributed) samples that follow the target distribution to generate additional new samples. To achieve this objective, it is essential to find a distribution that is as close to the target distribution as possible and then sample from it. Typically, the probability distribution is represented using the score function, where the score function is the gradient of the log of the probability density function \(\nabla_{x} \log p_{t} (x_{{\text{t}}} )\). Score-based diffusion model is a method of estimating data distribution through the optimization of a parameterized score network. The model incorporates both forward and reverse time diffusion processes, with the forward time diffusion process commonly referred to as SDE, as shown in Fig. 1. By gradually injecting noise (Gaussian noise is chosen in this article) into the dataset, the complex data distribution is smoothly transformed into a known prior distribution. Subsequently, by progressively removing the noise, the prior distribution is transformed back into the data distribution. The reverse-time SDE relies only on the time-dependent gradient field of the perturbed data distribution, also known as the score. Through the application of score-based diffusion model, neural networks can effectively estimate these scores, and by combining numerical SDE solvers with the noise conditional score network (NCSN) method, sampling can be conducted to generate defocus deblurring images. In addition, the concept of a predictor–corrector (PC) sampler is introduced, which offers dual advantages in terms of discretization error control and numerical stability. The sampling result of the numerical SDE solver is taken as the predictive result, while the annealed Langevin dynamics method acts as a corrector to correct the marginal distribution of the estimated samples, thus generating images with more apparent defocus deblurring effects.

\((x_{t} )_{t = 0}^{T}\) is assumed to be a continuous diffusion process with \(x_{t} \in {\mathbb{R}}\), where \(t \in \left[ {0,T} \right]\) is a continuous-time variable. \(x_{0} \sim p_{data}\), \(p_{data}\) represents the data distribution of the target image \(x_{T} \sim p_{T}\) (\(p_{T}\) is the prior distribution containing \(p_{data}\) information) is the prior distribution related to the target learned during the forward SDE process. The representation of the forward SDE is shown in Eq. (3).

In this formula, \(f(x,t) \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{}}\) and \(g(t) \in {\mathbb{R}}\) represent the drift coefficient and diffusion coefficient, respectively. \(w \in {\mathbb{R}}^{{}}\) and \(w\) represent the Brownian motion process. To sample from the data distribution, NCSN can be trained to estimate the gradient of the log data distribution \(\nabla_{x} \log p_{t} (x_{t} )\), instead of the data density \(p(x)\). The gradient can then be used to solve the reverse-time SDE to generate data from noise. Through this method, the capabilities of neural networks can be employed to model complex data distributions and introduce noise in the generation process to facilitate sample generation.

Figure 6 shows the forward and reverse SDEs. During the training process of the forward SDE, prior information related to the target \(x(T) \sim p_{T}\) is learned. Then, the reverse problem of Eq. (3) is solved, ultimately obtaining samples \(x(0) \sim p_{data}\). This reverse process can also be represented as a reverse-time SDE, as shown in Eq. (4). The reverse-time SDE is a diffusion process that converts the prior distribution back to the data distribution by gradually removing noise.

In this process of reverse diffusion, \(\overline{w}\) is the standard Wiener process, which represents time reversing from \(T\) to 0. \(dt\) represents an infinitesimally small negative time step. Once the score function \(\nabla_{x} \log p_{t} (x_{t} )\) of the marginal distribution at each time point \(t\) is known, the reverse diffusion process can be expressed as Eq. (4) and sampling simulations can start from \(p_{0}\). This process allows for the reverse reconstruction of data distributions based on known score information, thus generating samples. By selecting different parameters for \(f(x,t)\) and \(g(t)\), various SDEs can be constructed. In this paper, a Variance Exploding (VE) SDE is chosen as the core framework of the diffusion process, mainly based on its theoretical advantages in the dynamic range of noise scale and iterative refinement capability, which are highly compatible with the needs of the defocusing deblurring task. VE-SDE is defined as shown in Eq. (5):

where \(\sigma (t)> 0\) is a monotonically increasing function of the noise scale. To solve Eq. (4), a perturbation kernel \(p_{\sigma } (\tilde{x}|x): = N(\tilde{x};x,\sigma^{2} I)\) is established. The positive noise scale is expressed as shown in Eq. (6):

where \(\sigma_{\min }\) is sufficiently small and \(\sigma_{\max }\) is sufficiently large so that \(p_{{\sigma_{\min } }} (x) \approx p_{data} (x)\) and \(p_{{\sigma_{\max } }} \approx {\rm N}(x;\sigma_{\max }^{2} I)\). This design allows the noise variance to “explode” with time in the forward diffusion process. In the reverse process, the model needs to be iteratively refined from high noise levels to low noise levels. This wide range of noise spans allows more flexibility in covering the multiscale nature of the defocus blur, thus supporting the model’s gradual recovery of high-frequency details during the inverse process. Next, NCSN \(S_{\theta } (x_{t} ,t)\) is trained to approximate the gradient of the log data distribution at each time step. The training process is shown in the upper part of Fig. 7. To solve Eq. (4), the score function needs to be known for all time steps. The unknown \(\nabla_{x} \log p_{t} (x_{t} )\) can be replaced with \(\nabla_{x} \log p_{t} (x_{t} |x_{0} )\) using the denoising score matching43 with the help of NSCN, where \(\nabla_{x} \log p_{t} (x_{t} |x_{0} )\) is the gradient of the Gaussian perturbation kernel centered at \(x_{0}\). During the denoising score matching training, the parameters of the score network \(S_{\theta } (x_{t} ,t)\) are optimized according to Eq. (7):

where \(E_{t} \left\{ {\lambda (t)E_{{x_{0} }} E_{{x_{t} |x_{0} }} \left[ {\left\| {S_{\theta } (x_{t} ,t) - \nabla_{{x_{t} }} \log p_{t} (x_{t} |x_{0} )} \right\|_{2}^{2} } \right]} \right\}\) represents the loss function. After the network is trained through Eq. (7), the reverse-time SDE can be solved approximately using conditional \(S_{\theta } (x_{t} ,t) \simeq \nabla_{x} \log p_{t} (x_{{\text{t}}} )\), enabling the deblurring and reconstruction of defocus images, as indicated by Eq. (8):

To correct errors in the discretized evolution of the reverse-time SDE, PC sampling is introduced, as shown in the lower part of Fig. 7. The score-based diffusion model initially generates preliminary predicted reconstruction images by numerically solving the reverse-time SDE as predictions. Then the annealed Langevin method is employed as a corrector to adjust the marginal distribution of the estimated samples, thus refining the initial predictions. The prediction process is shown in Eq. (9). The target image \(\tilde{x}_{i}\) is generated from the prior distribution learned.

where \(\sigma_{i}\) is the noise scale, \(z\) is zero-mean Gaussian white noise, and \(i\) represents the number of discrete steps (i.e., iterations) in the reverse-time SDE. The correction algorithm shown in Eq. (10) is used to correct the marginal distribution of the estimated samples.

After the PC sampling updates, a singular data operation is required, as shown in Eq. (11). This operation constrains the generated images, enhancing image details, reducing artifacts or other unrealistic features, and thus making the generated images more realistic and credible.

The pseudocode for the defocus deblurring algorithm in this article is given as Algorithm 1, which includes two main loops: (1) The outer loop, the defocus image, enters the network for an initial prediction and then proceeds to the inner loop for correction; (2) The inner loop corrects the prediction through 1,000 iterations of annealed Langevin. Throughout the entire loop iteration process, both the data prior and data fidelity terms for prediction and correction are updated. The defocus images are deblurred through these 1,000 iterations.

The network structure of NCSN

The following diagram illustrates the network structure of NCSN for the forward SDE, as shown in Fig. 8, where R, C and A represent residual block, convolutional layer and attention block, respectively. Convolutional layers serve as feature extractors, retaining the main components of objects in the image while eliminating noise. The convolutional kernels are sized 3 × 3. The feature maps then undergo down-sampling to decrease their spatial dimensions. The features are subsequently processed by a sequence of residual blocks. Following a series of residual blocks, an attention mechanism block is added to improve the ability of the feature maps to convey information at specific resolutions. The feature maps proceed to the up-sampling phase to increase their spatial dimensions. In this part, features are processed through a sequence of residual blocks and up-sampled as needed. Up-sampling can be done through simple interpolation or convolutional up-sampling (chosen based on configuration). An attention mechanism block can be added after each residual block. Ultimately, through a series of convolutional and normalization layers, the required prior information is obtained. The input and output layers of the NCSN network have one channel each.

Dataset acquisition and network parameter introduction

After data preprocessing, the dataset used in this study consists of approximately 23,000 images, derived from the images captured with a Sony RX100III camera in Nanchang University campus scenes and part of Dual-Pixel Defocus Deblurring (DPDD)44 dataset. The images captured with the Sony RX100III camera supplement the DPDD dataset, adding a diverse array of real scenes that occur within the dynamic environment of Nanchang University’s campus. The DPDD dataset contains 500 carefully captured scenes. This dataset consists of 2,000 images, including 500 DoF blurred images with their 1,000 dual-pixel sub-aperture views and 500 corresponding all-in-focus images. The diversity allows the dataset to effectively simulate various blurring scenarios encountered in the real world, providing robust support for the evaluation of defocus deblurring. Selected parts of the dataset are shown in Fig. 9.

This study also additionally included two datasets, Real-World Blur (RealBlur)45 and Defocus Image Deblurring (DED)46, for testing. The RealBlur dataset, captured using the Sony A7RM3 camera paired with the Samyang 14 mm F2.8 MF lens, is a large-scale real-world blurred image dataset designed to support the learning and benchmarking of deblurring algorithms. This dataset contains 3,758 pairs of images for training and 980 pairs of images for testing, covering 182 different scenes. The DED dataset captured by using the Lytro Illum light field camera is the first large-scale real-world dataset used for defocus map estimation and defocus image deblurring, which includes both defocus and focused images. Through testing on different datasets, a more comprehensive assessment of the proposed method’s performance under various application scenarios can be conducted.

The images were resized to 256 × 256 and underwent 1,000 iterations during the image generation process. The learning rate was configured as 2 × 10–4, and pixel values were normalized before being fed into the network. To enhance the diversity of samples, a range of larger \(\sigma\) values could be sought in setting the perturbation kernel \(p_{\sigma } (\tilde{x}|x): = N(\tilde{x};x,\sigma^{2} I)\). However, excessively large \(\sigma\) values would lead to a greater noise scale, necessitating more memory capacity to support the simulated Langevin dynamics process and subsequently increasing the computation time. In order to balance the diversity of perturbations with the stability of training, the range of \(\sigma\) was empirically set between 0.01 and 300. Gaussian noise was employed to perturb the data distribution to achieve a better defocus deblurring effect. The method was implemented using the PyTorch framework and mainly developed in a Python environment. The model was trained and optimized using the Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam) method. In this work, the computation is performed on a graphical processing unit (GPU; GeForce RTX 2080Ti).

The training of the model involves estimating the unknown score function by training a score network. Throughout the training process, it is necessary to continuously add noise to the training data and learn the data distribution. The duration of training varies depending on the various levels of noise. Additionally, the training duration of the proposed method also depends on the configuration of the graphics processing unit employed in the experiment and the quantity and size of the training dataset. During the training phase, a checkpoint is saved every 10,000 epochs, which takes approximately 40 min. A total of 30 checkpoints were obtained in this experiment, and the optimal training model was selected. Defocus deblurring is an iterative process. As observed from Fig. 4, the iterative process stabilizes around the 700th iteration, with each iteration taking about 1s. Therefore, the defocus deblurring process takes approximately 12 min.

Ablation studies

The proposed method has three components that can output the defocus deblurring images: the reverse-time SDE, the annealed Langevin algorithm, and the gradient descent operation. To evaluate the respective contributions of these components, ablation experiments were conducted on these three components within the self-captured dataset. The evaluation metrics are PSNR and SSIM. However, since the input of the annealed Langevin operation is the result of the reverse-time SDE, it is impossible to test the annealed Langevin operation alone.

The test results are shown in Table 1. It can be seen from the experimental results that the test results of using the reverse-time SDE alone are rather poor. The average PSNR and SSIM of the output deblurring images are only 11.1 dB and 0.21, respectively. This is because the reverse-time SDE has inherent limitations when used alone. Without the correction mechanism of subsequent steps, the initial prediction of the reverse-time SDE tends to be overly smooth and fails to effectively restore the details in the original image. After introducing the annealed Langevin algorithm, the PSNR and SSIM are increased by 2.2 dB and 0.07, respectively. This is because the main function of the annealed Langevin algorithm is to correct the marginal distribution. Although it can bring about certain improvements, the improvement effect is relatively limited. However, after combining with the gradient descent operation for data consistency, both the PSNR and SSIM of the test results have achieved a qualitative leap. This indicates that the gradient descent operation plays a crucial role in refining the generated images by forcibly maintaining the consistency between the output images and the original input. This process not only helps to reduce artifacts but also enhances the details that are often lost during the initial prediction process. The fact that the PSNR and SSIM have respectively increased to an average of 26.79 dB and 0.84 indicates that the integration of the gradient descent provides a powerful mechanism, which can ensure a close connection between the generated images and those in the real scene. The comparison of each component presented in Table 1 not only reflects the effectiveness and contribution of each component but also provides insights for subsequent model optimization work, ensuring the universality and effectiveness of this model under a series of conditions.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the GitHub repository, https://github.com/yqx7150/HIDD-DM.

References

Quan, Y., Wu, Z. & Ji, H. Gaussian kernel mixture network for single image defocus deblurring. Adv. Neural. Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 20812–20824 (2021).

H. Noh, S. Hong, and B. Han, “Learning deconvolution network for semantic segmentation” In 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV, 2015) 1520–1528.

L. Wang, D. Li, Y. Zhu, and Y. Shan, “Dual super-resolution learning for semantic segmentation” In 2020 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR, 2020) 3773–3782.

J. Dai, Y. Li, K. He, and J. Sun, “R-fcn: Object detection via region-based fully convolutional networks,” In Advances in neural information processing systems (NeurIPS, 2016) 379–387.

J. Cao, H. Cholakkal, R. M. Anwer, F. S. Khan, Y. Pang, and L. Shao, “D2det: Towards high quality object detection and instance segmentation” In 2020 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR, 2020) 11485–11494.

Pertuz, S., Puig, D. & Garcia, M. A. Analysis of focus measure operators for shape-from-focus. Pattern Recognit. 46(5), 1415–1432 (2013).

Muhammad, A. & Choi, T. S. Depth from defocus using wavelet transform. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 87(1), 250–253 (2004).

P. Favaro and S. Stefano, “Learning shape from defocus,” In 2002 European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV, 2002) 735–745.

Mueller, N., Lu, Y. & Do, M. N. Image interpolation using multiscale geometric representations. Comput. Imaging V. SPIE. 6498, 89–99 (2007).

Lim, H., Tan, K. C. & Tan, B. T. G. Edge errors in inverse and wiener filter restorations of motion-blurred images and their windowing treatment. CVGIP Graphical Models & Image process. 53(2), 186–195 (1991).

Liu, N., Zheng, X., Sun, H. & Tan, X. Two-dimensional bar code out-of-focus deblurring via the increment constrained least squares filter. Pattern Recognit Lett. 34(2), 124–130 (2013).

Cojocari-Goncear, M. Digital image deblurring techniques a comprehensive survey. Conferinţa tehnico-ştiinţifică a studenţilor, masteranzilor şi doctoranzilor 1, 355–360 (2022).

Dabov, K., Foi, A., Katkovnik, V. & Egiazarian, K. Image denoising by sparse 3-D transform-domain collaborative filtering. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 16(8), 2080–2095 (2007).

Varghese, N. et al. Fast motion-deblurring of IR images. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 29(459), 463 (2022).

A. Goldstein and R. Fattal, “Blur-kernel estimation from spectral irregularities,” In 2012 European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV, 2012) 622–635.

J. Pan, Z. Hu, Z. Su, and M. H. Yang, “Deblurring text images via L0-regularized intensity and gradient prior,” In 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR, 2014) 2901–2908.

J. Lee, H. Son, J. Rim, S. Cho, and S. Lee, “Iterative filter adaptive network for single image defocus deblurring,” In 2021 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR, 2021) 2034–2042.

Nazir, S., Vaquero, L., Mucientes, M., Brea, V. M. & Coltuc, D. Depth estimation and image restoration by deep learning from defocused images. IEEE Trans. Comput. Imaging. 9, 607–619 (2023).

Zha, Z. et al. Triply complementary priors for image restoration. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 30, 5819–5834 (2021).

Zha, Z., Yuan, X., Zhou, J., Zhu, C. & Wen, B. Image restoration via simultaneous nonlocal self-similarity priors. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 29, 8561–8576 (2020).

Zha, Z. et al. Low-rankness guided group sparse representation for image restoration. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learn. Syst. 34(10), 7593–7607 (2023).

S. W. Zamir, A. Arora, S. Khan, M. Hayat, F. S. Khan, M. H. Yang, and L. Shao, “Multi-stage progressive image restoration,” In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR, 2016) 14821–14831.

S. J. Cho, S. W. Ji, J. P. Hong, S. W. Jung, and S. J. Ko, “Rethinking coarse-to-fine approach in single image deblurring,” In 2021 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR, 2021) 4641–4650.

K. Zhang, W. Luo, Y. Zhong, L. Ma, B. Stenger, W. Liu, and H. Li, “Deblurring by realistic blurring,” In 2020 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR, 2020) 2737–2746.

X. Tao, H. Gao, X. Shen, J. Wang, and J. Jia, “Scale-recurrent network for deep image deblurring,” In 2018 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR, 2018) 8174–8182.

Wang, K. et al. Generative adversarial networks: Introduction and outlook. IEEE-CAA J. Automatic. 4(4), 588–598 (2017).

Y. Song, C. Durkan, I. Murray, and S. Ermon, “Maximum likelihood training of score-based diffusion models,” In Advances in neural information processing systems (NeurIPS, 2021) 34, 1415–1428.

Fan, S. et al. Unsupervised deep learning for 3D reconstruction with dual-frequency fringe projection profilometry. Opt. express 29(20), 32547–32567 (2021).

He, J. et al. Semi-supervised learning for optical fiber sensor road intrusion signal detection. Appl. Opt. 61(6), C65–C72 (2022).

Y. Song and S, Ermon, “Improved techniques for training score-based generative models,” In Advances in neural information processing systems (NeurIPS, 2020) 33, 12438–12448.

Y. Song, J. Sohl-Dickstein, D. P. Kingma, A. Kumar, S. Ermon, and B. Poole, “Score-based generative modeling through stochastic differential equations” arXiv arXiv:2011.13456 (2020).

Zhang, K., Zuo, W. & Zhang, L. FFDNet: Toward a fast and flexible solution for cnn-based image denoising. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 27(9), 4608–4622 (2018).

Zhang, K., Zuo, W., Chen, Y., Meng, D. & Zhang, L. Beyond a gaussian denoiser: Residual learning of deep cnn for image denoising. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 26(7), 3142–3155 (2017).

J.-Y. Zhu, T. Park, P. Isola, and A. A. Efros, “Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks” In Proc. of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) Venice Italy 2017 2223–2232.

H. Chung, B. Sim and J. C. Ye, “Come-closer-diffuse-faster: Accelerating conditional diffusion models for inverse problems through stochastic contraction” In 2022 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR, 2022) 12413–12422.

Z. Luo, F. K. Gustafsson, Z. Zhao, J. Sjölund and T. B. Schön, ”Image restoration with mean-reverting stochastic differential equations” arXiv arXiv:2301.11699 (2023).

S. Hong, G. Lee, W. Jang and S. W. Kim, “Improving sample quality of diffusion models using self-attention guidance,” In 2023 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV, 2023) 7462–7471.

D. X. Li, W. Xie, Z. X. Wang, Y. B. Lu, Y. S. Li and L. Y. Fang, “FedDiff: diffusion model driven federated learning for multi-modal and multi-clients” arXiv, arXiv:2401.02433 (2023).

Song, X. et al. Multiple diffusion models-enhanced extremely limited-view reconstruction strategy for photoacoustic tomography boosted by multi-scale priors. Photoacoustics. 40, 2213–5979 (2024).

Hyvärinen, A. & Dayan, P. Estimation of non-normalized statistical models by score matching. J Mach Learn Res. 6(4), 695–709 (2005).

K. Hong, C. Wu, C. Yang, M. Zhang, Y. Lu, Y. Wang, and Q. Liu, “High-dimensional assisted generative model for color image restoration” arXiv, arXiv:2108.06460 (2021).

Roberts, G. O. & Tweedie, R. L. Exponential convergence of Langevin distributions and their discrete approximations. Bernoulli 2(4), 341–363 (1996).

Vincent, P. A connection between score matching and denoising autoencoders. Neural Comput. 23(7), 1661–1674 (2011).

A. Abuolaim and M. S. Brown, “Defocus deblurring using dual-pixel data,” In 2020 European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV, 2020) 111–126.

J. Rim, H. Lee, J. Won, and S. Cho, “Real-world blur dataset for learning and benchmarking deblurring algorithms” In 2020 European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV, 2020) 12370 184–201.

Ma, H. Y., Liu, S. J., Liao, Q. M., Zhang, J. C. & Xue, J. H. Defocus image deblurring network with defocus map estimation as auxiliary task. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 31, 216–226 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Zehao Sun, Guijun Wang and Kangjun Guo from School of Information Engineering, Nanchang University for helpful discussions.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (62265011); Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (20224BAB212006, 20232BAB202038); Training Program for Academic and Technical Leaders of Major Disciplines in Jiangxi Province (20243BCE51138); National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFF1204302).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LYH, FHR, LX and WQ collected data, tested and analyzed the samples, and wrote the paper. FHR and LX added experimental validation and revised the paper. LQG and SXL provided technical support. HG, LJB, DJQ, LZL, and SXL offered suggestions for modification. Source apportionment was conducted by WQ, LYH, LQG, and SXL. All authors contributed to the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Video 1.

Supplementary Video 2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Fang, H., Lei, X. et al. Real-world defocus deblurring via score-based diffusion models. Sci Rep 15, 22942 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07326-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07326-6