Abstract

Asthma is a significant global health issue, especially in high-altitude areas where unique environmental conditions and socioeconomic disparities may elevate disease risk and severity. This study examines the prevalence and determinants of asthma among the Gujjar and Bakarwal tribes living in the high-altitude regions of the western Himalayas, providing insights into the influence of altitude, socioeconomic factors, and lifestyle on asthma risk. We conducted a cross-sectional survey across 816 households in 50 villages in Poonch and Rajouri districts, utilizing a stratified random sampling approach to ensure a representative sample. Villages were categorized by altitude and population density. Geographic Information System (GIS) tools were used to map asthma prevalence using inverse distance weighting (IDW) and Natural Breaks classification to identify high-risk zones. To determine asthma risk factors, we applied a binary logistic regression model (BLRM), with model fit assessed via pseudo-R² and Hosmer-Lemeshow tests, and predictive accuracy evaluated through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Asthma prevalence was 22.5% among the study population. Higher altitudes were linked to a significantly lower likelihood of asthma (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 0.10, p = 0.002). In contrast, extended family living arrangements (AOR: 8.80, p = 0.008) and individuals in their prime working years (AOR: 93.36, p = 0.001) showed elevated asthma risk. Protective factors included higher education, government employment, farming, increased household income, and residence in modern housing. The model exhibited strong fit (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.82) and high predictive accuracy (ROC-AUC = 0.98). Asthma prevalence among Gujjar and Bakarwal tribes in the high-altitude Himalayas is shaped by a complex interplay of altitude, socioeconomic status, and demographic factors. Altitude appears protective, while social structure, economic activities, and housing conditions modulate asthma risk. GIS-based spatial analysis effectively identifies high-risk areas, underscoring the need for targeted public health interventions tailored to the specific needs of these geographically isolated communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Asthma is a common chronic inflammatory disease of the airways, characterized by recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and coughing. It affects approximately 300 million individuals worldwide, with projections estimating an increase to 400 million by 20251,2. Globally, asthma imposes a significant public health burden, contributing to approximately 250,000 deaths annually3. Over the past decades, both genetic and environmental factors, intertwined with lifestyle changes in modern society, have contributed to the rising incidence of asthma4,5.

Asthma prevalence has been increasing in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), largely due to economic globalization, rapid urbanization, and industrialization6,7,8. These factors have led to greater exposure to outdoor and indoor pollutants, which can exacerbate or trigger asthma symptoms9. Additionally, limited access to healthcare resources in LMICs poses a significant challenge to asthma diagnosis, treatment, and prevention9. Pathophysiologically, asthma is a complex condition involving airway inflammation, hyperresponsiveness, and reversible obstruction, leading to episodic wheezing, coughing, chest discomfort, and shortness of breath. These symptoms are often triggered by allergens, irritants, and respiratory viral infections10. The severity of asthma varies widely, ranging from mild symptoms to severe, persistent asthma that significantly impacts patients’ lives and increases the risk of mortality11.

Asthma incidence is highest in childhood, with global rates estimated at 23 per 1000 children under five years of age, declining to 4.4 per 1000 among adolescents12. However, recent data indicate that childhood asthma remains a growing concern in some regions due to rising environmental pollutants and lifestyle factors11. Gender differences are also evident, with women having a 1.8-fold higher risk of asthma compared to men during adulthood, likely influenced by hormonal fluctuations associated with adolescence, menstruation, pregnancy, and menopause13. These hormonal shifts can exacerbate airway inflammation, increasing asthma susceptibility.

Environmental factors also play a crucial role in asthma development and progression. Smoking (both active and passive) is a well-documented risk factor, alongside exposure to airborne allergens, industrial pollutants, and occupational hazards14,15. Additionally, lifestyle factors such as obesity, sedentary behavior, and unhealthy diets have been linked to an increased risk of asthma2,12.

The burden of asthma is disproportionately high in lower-income populations, particularly in LMICs, where 96% of all asthma-related deaths occur9. Individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to face poor housing conditions, indoor air pollution, and reliance on solid fuels for cooking, all of which are preventable risk factors for respiratory disease16. Limited access to healthcare further exacerbates asthma severity in these populations.

Economic constraints hinder access to medications, preventive care, and specialized treatment, leading to poor disease management17,18. Occupational exposure to pollutants, dust, and hazardous chemicals—common in low-income jobs—further amplifies asthma risk19,20. Lower educational attainment also limits health literacy, reducing the ability to effectively manage asthma17. Moreover, economic stress correlates with higher obesity rates and lower medication adherence, both of which worsen asthma control18,21.

Asthma management is particularly challenging in high-altitude regions like the Himalayas, where environmental factors such as cold, arid air, high pollen levels, and reduced oxygen pressure can exacerbate symptoms22,23,24,25. Additionally, fungal spores and airborne pollutants at high altitudes further contribute to respiratory complications.

The Gujjar Bakarwal, a semi-nomadic ethnic group residing in the Himalayan region, face unique respiratory health challenges due to their seasonal migration patterns. Their frequent movement between summer pastures (2,500–3,500 m) and winter valleys (300–2,000 m) disrupts physiological adaptation to environmental changes, increasing their vulnerability to asthma. Limited healthcare access and reliance on traditional heating and cooking methods further compound these challenges.

Despite growing research on asthma in urban and industrialized areas, data on asthma prevalence among high-altitude, semi-nomadic populations remain scarce. While studies in India have highlighted the role of socioeconomic, environmental, and behavioral factors in asthma prevalence26,27,28,29specific risk factors among marginalized, high-altitude tribal populations like the Gujjar Bakarwal are poorly understood. This study aims to examine the interplay of environmental, cultural, social, and economic factors influencing asthma prevalence among the Gujjar Bakarwal population. The analysis will focus on variables such as (i) altitude, (ii) age, gender, marital status, and family structure, (iii) socioeconomic status (income, education, occupation), (iv) housing conditions, heating systems, kitchen location, and cooking fuel and (v) water sources and behavioral factors (smoking, tobacco use, etc.)

To assess the probability of asthma occurrence, we will employ a Binary Logistic Regression Model (BLRM), which is well-suited for analyzing binary outcomes (asthma diagnosis: yes/no). Forward selection will be used to refine the model by iteratively adding the most significant predictors based on their contribution to model fit, assessed using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and p-values. Additionally, spatial analysis will be conducted to map asthma prevalence and identify regional trends, offering insights into the potential effects of altitude and environmental factors. The combination of these methodologies will provide a comprehensive understanding of asthma risk in high-altitude populations, guiding the development of targeted prevention and treatment strategies.

By focusing on the Gujjar Bakarwal, this study seeks to address the unique health challenges faced by semi-nomadic populations in resource-limited, high-altitude environments. Findings from this research will contribute to public health policies aimed at improving asthma management in marginalized communities and will have broader implications for asthma prevention in high-altitude settings worldwide.

Data and methods

Profile of the study area

The study area encompassed the Rajouri and Poonch districts, located in the south-eastern foothills of the Pir Panjal Range within the Indian Himalayan Region featuring hilly and mountainous areas interspersed with low-lying valleys (Fig. 1). The elevation ranges from 314 to 4713 m above the sea level30,31 leading to varied weather conditions, including snow cover during winter months. The climate transitions from sub-tropical at lower elevations to temperate, sub-alpine and alpine at higher altitudes. At lower elevations (< 1000 m), summers can reach temperatures between 25 and 35 °C, while winters are mild to cool, ranging from 5 to 15 °C. Mid-elevations (1000–2000 m), experience moderately warm summers (20 °C to 30 °C) and cooler winters (0–10 °C). At higher elevations (> 2000 m), summers are cool (10 –20 °C) and winters harsh, with temperatures ranging from (− 10 to 5 °C) and heavy snowfall.

According to the 2011 Census, the combined population of Rajouri and Poonch districts is projected to reach 1,494,900 by 2024, with Rajouri accounting for 874,000 and Poonch for 621,000. Both districts have experienced significant population growth since 2011, with Rajouri increasing by 32.9% and Poonch by 28.0%. Rajouri covers an area of 2630 km2, with a population density of 244 individuals per km2, while Poonch spans 1674 km2, with a density of 285 individuals per km².

The sex ratios in Rajouri and Poonch stand at 860 and 893 females per 1000 males, respectively. Encouragingly, the child sex ratio is slightly higher—865 in Rajouri and 893 in Poonch—indicating progress toward gender equity. The average literacy rate in the region is 68.2%, with children comprising 16.9% of Rajouri’s population and 17.8% of Poonch’s.

The region is home to diverse linguistic groups, with the nomadic Gujjar and Bakarwal communities forming the majority, constituting approximately 60% of the population. Historically, these tribes have thrived as nomadic pastoralists, maintaining a deep connection with the land’s natural rhythms. While both groups rely on the region’s ecosystems for sustenance, their livelihood practices differ: Bakarwals primarily herd sheep and goats, whereas Gujjars specialize in buffalo and cattle rearing32. This symbiotic relationship between the tribes and their environment underscores the intricate balance between traditional knowledge and sustainable living in both districts.

Data

Primary data

Primary data were collected between June 13th to August 13th, 2023, via face-to-face interviews using a pre-tested and validated household schedule (HHS). This HHS was developed after a thorough a review of existing literature on asthma risk factors in high-altitude populations2,12,16,26,27,28,29 covered various sections.

Asthma status (the outcome variable) was binary, with ‘1’ indicating presence and ‘0’ indicating absence. Explanatory variables were classified into geographical, demographic, socioeconomic, environmental, and behavioural domains, with comprehensive descriptions and coding given in Table 1.

Confidentiality and anonymity

To ensure the privacy of participants, the HHS was designed to omit personally identifiable information. The collected data were securely stored, maintaining strict confidentiality in line with ethical research standards.

Data cleaning and validation

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the collected data, a rigorous cleaning and validation process was implemented. The household schedule (HHS) was pre-tested on 60 individuals across three elevation zones to identify and address any ambiguities or inconsistencies. The finalized schedule was used to collect data from 408 households in each district (Poonch and Rajouri), yielding a total of 816 households. The collected data were reviewed for completeness at the time of collection, with no missing responses recorded due to on-site verification.

After data collection, responses were entered into Microsoft Excel, where a double-entry process and random cross-checking of 10% of the entries ensured consistency and eliminated errors33. Logical and range checks were conducted to identify and correct anomalies by consulting the original schedules34. The validated dataset was transferred to SPSS (Version 26.0) for statistical analyses, where additional validation checks confirmed data integrity. These steps ensured a robust dataset suitable for both statistical and geospatial analyses.

Geospatial data collection

The geographical location of each surveyed household was recorded using Garmin GPSMAP 64s device with a horizontal accuracy of ± 3 m under open-sky conditions. Potential errors due to signal obstruction in mountainous terrain (e.g., steep slopes, dense vegetation) were minimized by validating coordinates against DEM-derived elevations during post-processing35.

To ensure the accuracy of the collected coordinates and interpolation, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the effect of varying Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) parameters36such as power and search radius, on the final spatial probability estimates. This analysis was essential for evaluating the robustness of the spatial model and confirming that the resulting maps accurately represent the geographical distribution of asthma.

Secondary data

Secondary data included village positions and elevations were acquired from the Census of India 2011[https://www.census2011.co.in/census/district/623-punch.html], [https://www.census2011.co.in/census/district/624-rajouri.html]. The altitude zones within the study area were delineated using the Digital Elevation Model (DEM) with a 30-meter resolution [https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/], and village shapefiles.

Study design and sampling strategy

The study area was divided into six distinct elevation zones by categorizing three elevation ranges (high, medium and low) from each of the two districts (Table 2; Fig. 2). This classification was achieved using the Natural Breaks method37 based on DEM contour data. The classification of elevation zones differs between Rajouri and Poonch due to unique geographic and topographic characteristics, such as differences in slope gradient, terrain ruggedness, and microclimatic conditions. These factors necessitated tailoring elevation ranges to capture meaningful ecological and demographic variability within each district. In Rajouri, lower elevations extend down to 314 m, reflecting broader lowland valleys and gentler slopes. In contrast, Poonch features steeper terrain, with its low zone starting at 560 m. Middle and high elevation zones also vary due to the distinct geographical and hydrological features influencing these ranges.

This stratification provides a comprehensive representation of geographical and demographic variations within the study area. It captures the influence of elevation-related factors on health outcomes, ensuring diverse environmental and climatic conditions are considered. The Natural Breaks method effectively identifies significant variations in elevation.

Village selection and sampling framework

A four-stage stratified sampling design was implemented: Stage 1 (Districts): Poonch and Rajouri. Stage 2 (Elevation Zones): High, middle, and low zones per district. Stage 3 (Villages): Proportional allocation based on population density and elevation. Stage 4 (Households): Systematic random sampling within selected villages.

Villages were stratified into three categories based on elevation and population density. This stratification was essential to capture health disparities influenced by altitude-related factors, such as temperature, oxygen levels and population density, which affect access to healthcare services.

A proportional allocation method was applied to ensure villages were distributed across strata, accounting for district population densities (Rajouri: 244/km2 vs. Poonch: 285/km2) and geographical distribution to represent elevation gradients38. This resulted in selecting 34 villages in Rajouri and 16 in Poonch, reflecting their population densities and terrain variability. In total, 50 villages (10% of the study area) were sampled (Supplementary_File_S1 (Table 1D).

Household sampling and respondent selection

The sample size was calculated using the Krejcie and Morgan formula, preferred over Cochran’s formula due to its optimization for finite population (Rajouri: N = 229,361: Poonch: N = 168,908)39. The formula is as follows:

where n is the required sample size; N the population size; X2 the chi-square value for 1 degree of freedom at the desired confidence level (3.841 for 95% confidence intervals (CIs); P the estimated population proportion (assumed to be 0.5 for maximum variability); and \(\:d\:\)the margin of error (5%).

Using (1), the minimum required sample size was 384 households for Rajouri and 383 households for Poonch. The final sample size was increased to 408 households per district (6% oversampling) to account for non-responses and logistical challenges in mountainous terrain, such as seasonal migration and accessibility barriers, ensuring robust representation of subpopulations in heterogeneous terrains40. Households were then selected using systematic random sampling.

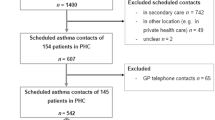

This sample represented approximately 5% of households in selected villages. In each selected household, the survey targeted member aged 18 years or older available at the time of the survey, using a convenience sampling method. This ensured a wide cross-section of the population while addressing potential biases through oversampling and post-survey adjustments. For detailed breakdown of sample selection procedures and household distribution, see Fig. 3 and Supplementary_File_S1 (Tables 1A, B, C and D).

Statistical analysis

Village locations and disease prevalence were analysed using inverse distance weighting (IDW) interpolation to estimate the likelihood of asthma occurrence across the study area. The probability of asthma occurrence was divided into five categories using Natural Breaks with IDW interpolation37 and Zonal Statistics41 utilized to summarize the interpolated asthma probability data for each altitude zone. Subsequently, choropleth maps were generated based on the statistical results of the Binary Logistic Regression Model (BLRM).

BLRM is a statistical method used to estimate the probability of an event occurring, such as asthma, using independent variables as predictors, which can include both continuous and categorical data. In a BLRM, the model’s structure is represented by Eq. (2):

where pi represents the probability of having asthma (the expected value of the dependent variable yi, where yi = 1, if a sample has disease; otherwise yi = 0); \(\:x\:\)the independent variables (potential factors of exposure); β the estimated coefficient; and i index records, e.g., geographic units. Variables are typically included in the model based on levels of significance, often set at 0.05 or 0.1.

BLRM is widely used for analyzing spatially correlated data, such as the presence or absence of a disease. It incorporates a spatial autocorrelation term through weighting coefficients, addressing spatial autocorrelation effects during statistical analysis. The conditional probability of the occurrence can be expressed using Eq. (3):

In this equation, pi denotes the probability of the event occurring for each geographic unit,\(\:\:x\:\)represent the independent variables; Autocov\(\:\text{i}\) the autocovariate variable; i the index of the geographical unit; and β and r the coefficients of the variables in the model.

A forward selection approach was applied to refine the BLRM, identifying the most important predictors by iteratively adding variables based on their contribution to model performance. At each step, the variable that enhances model performance the most is selected and evaluated using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) or p-values. This procedure continues until no further significant improvements are observed.

The fitness of BLRM in predicting asthma occurrence was evaluated using sample data. Goodness-of-fit tests including the Hosmer-Lemeshow test42Cox and Snell R²43Nagelkerke R²44and the − 2 log likelihood method44. Variables with a statistically significant association (p < 0.05) with asthma were included, adjusting for potential confounding factors. Pseudo R2 chi-square, odds ratios (ORs), adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% CIs were used to elucidate the strength and direction of these associations.

Validation of the BLRM model was conducted the ROC curve (Fig. 4). This graphical representation plots the true positive rate against the false positive rate, providing insights into the model’s diagnostic ability across various threshold settings.

The Area Under the Curve (AUC) was used to assess the model’s overall accuracy. The AUC value of 0.98 was obtained, indicating a high level of accuracy. Generally, an AUC value above 0.9 is considered excellent, with 1.0 representing perfect discrimination (Fig. 4).

While the near-perfect AUC value suggests excellent discriminatory performance, it also raises concerns about potential over fitting. To address this, several steps were taken to ensure the reliability and generalizability of the model:

-

(a)

Model Fit Assessment: The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test (p = 0.539) confirmed an excellent fit, with no significant difference between observed and predicted values. The Nagelkerke pseudo-R2 value (82.2%) further supports the model’s robustness.

-

(b)

Predictive Accuracy: The AUC value was statistically validated, confirming its robustness in distinguishing outcomes without over fitting.

-

(c)

Representative Sampling: A stratified random sampling method was employed to ensure a representative dataset, minimizing biases that could result in over fitting.

-

(d)

Geospatial Validation: Geographic Information Systems (GIS) analysis was utilized to validate spatial patterns of thyroid disorder prevalence, enhancing the model’s generalizability across the study region.

Furthermore, the ROC curve’s asymptotic significance, assessed through statistical testing, confirmed that the observed performance of the model is statistically significant and not due to chance. To further ensure model robustness, additional validation methods such as k-fold cross-validation or bootstrapping could be considered in future analyses. These techniques would provide further evidence of the model’s stability beyond the current validation measures employed.

The model was applied to the entire dataset in the study region for each factor and assessed using overall map accuracy and Kappa Index. Figure 5 depicts of the overall design and process.

Software used

Statistical analyses of asthma prevalence and independent variables were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Base Version 26.0, https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics. Spatial analysis and mapping of asthma prevalence and predictors were performed using ArcGIS. Geocoding of each sample patient’s locations was carried out using a Garmin GPSMAP 64s device.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 3 presents the sociodemographic and economic characteristics of the study population across six altitude strata. Gender distribution varied across zones, with Zone F (1,143–4,624 m) showing a slightly higher percentage of men than women, while other zones exhibited a more balanced distribution. Zone D (314–736 m) had a younger population structure, characterized by a higher proportion of individuals under 10 years old and fewer individuals over 60 compared to other zones.

Marital status was relatively consistent across all zones. A significant portion of the population lacked formal education, particularly in Zones A (32.1%) and F (28.9%), with Zones A and B exhibiting the highest rates of individuals without formal schooling. In contrast, Zone D had a higher proportion of individuals with secondary education.

Students were well-represented across all zones, while Zone A had a higher proportion of housewives. Zones C–F displayed a more diverse occupational landscape, with higher representation of herders, general laborers, and farmers.

Income distribution revealed that lower income brackets (<₹10,000 INR) were prevalent across all zones, with Zone A having a slightly higher proportion of individuals in the lowest income category (<₹5000 INR).

Outcomes of the spatial analysis

Our analysis of asthma prevalence across both districts highlights distinct patterns influenced by elevation. Males consistently exhibit a higher burden (56.0%) compared to females (44.0%), with altitude playing a key role in prevalence trends. Among males, asthma prevalence is highest at lower altitudes (60.0%), decreases slightly at middle altitudes (57.9%), and further declines at high altitudes (51.4%). In contrast, females show a potentially increasing trend with altitude, with prevalence rising from 40.0% at low altitudes to 42.1% at middle altitudes and 48.6% at high altitudes (Fig. 6A).

Marital status also interacts significantly with elevation. Married individuals consistently demonstrate higher asthma prevalence across all elevations, increasing from 75.5% at low altitudes to 85.1% at high altitudes. Conversely, single individuals exhibit a declining trend with increasing altitude, with prevalence dropping from 24.5% at low altitudes to 14.9% at high altitudes (Fig. 6B).

Settlement patterns further shape asthma prevalence. Among settled individuals, prevalence is highest at low altitudes (81.8%) and decreases as altitude increases (middle: 66.7%, high: 54.17%). In contrast, nomadic individuals experience an increasing trend, with prevalence rising from 18.2% at low altitudes to 45.8% at high altitudes (Fig. 6C).

Age also plays a critical role in asthma burden. Individuals over 61 years exhibit the highest overall prevalence (25.0%), with variation across elevations—27.3% at low altitudes, 17.5% at middle altitudes, and 29.2% at high altitudes. The 41–50 age group also bears a significant burden (21.7%), particularly in middle elevations, where prevalence peaks at 31.6% (Fig. 6D).

Education level interacts with altitude in shaping asthma prevalence. Individuals with no formal education exhibit the highest overall prevalence (46.2%), particularly in high-altitude regions (45.9%). Those with primary education show the highest prevalence at middle elevations (44.4%), whereas individuals with graduate and postgraduate qualifications maintain notable prevalence at both middle (50.0%) and high elevations (50.0%) (Fig. 6E).

Occupation patterns also vary across elevation zones. At low altitudes, students (24.1%), government employees (17.2%), and farmers (10.3%) represent the most affected groups. In middle elevations, farmers (29.2%) report the highest prevalence, followed by retired or ex-servicemen (16.7%) and laborers (12.5%). At high elevations, farmers (14.3%) and laborers (17.1%) remain prominent, alongside a growing presence of self-employed individuals (14.3%) (Fig. 6F).

At low elevations, individuals predominantly fall within the ₹10,001–₹15,000 income range (29.1%). In contrast, middle elevations show a higher prevalence of individuals in the lowest income bracket (less than ₹5,000: 33.3%). Interestingly, at high elevations, the highest proportion of individuals is again in the ₹10,001–₹15,000 range (40.3%) (Fig. 7G). Similarly, in low elevations, joint families experience the highest asthma burden (63.6%), a trend that continues at middle (45.6%) and high elevations (56.9%). Overall, joint families bear the greatest share of asthma cases (55.4%) (Fig. 7H).

Traditional houses show the highest asthma prevalence at all elevations (low: 52.7%, middle: 59.6%, high: 69.4%). Conversely, modern houses exhibit a decreasing trend in asthma prevalence with increasing altitude (low: 29.1%, middle: 35.1%, high: 13.9%). Nomadic and mixed house types generally have lower prevalence rates. Overall, traditional houses contribute the most to asthma prevalence (61.4%) (Fig. 7I). The use of Bhukhari (a traditional heating method) is strongly associated with asthma, with an overwhelming 95.1% prevalence, highlighting its impact on respiratory health (Fig. 7J).

Households with indoor kitchens report higher asthma rates: low (80.0%), middle (73.7%), and high elevations (79.2%). In contrast, homes with outdoor kitchens show significantly lower asthma prevalence (low: 20.0%, middle: 26.3%, high: 20.8%). These findings suggest a potential link between indoor kitchens and increased asthma risk (Fig. 7K). Regarding low and middle elevations, the use of Chullah (a traditional cooking stove) is linked to higher asthma rates (47.3% and 45.6%, respectively). At high elevations, where Chullah usage is most prevalent (69.4%), asthma rates are particularly high. In contrast, stove usage, which is associated with lower asthma prevalence, becomes more prominent at high elevations (25%), suggesting that modern cooking methods may offer health benefits (Fig. 7L).

Asthma prevalence varies with the main source of drinking water across elevations. Higher rates are observed among households relying on water springs: low (34.5%), middle (54.4%), and high elevations (58.3%). Our study suggests a potential association between water source and asthma prevalence (Fig. 8M). Perceptions of water cleanliness also impact asthma prevalence across different elevations. Higher asthma rates are seen where more people perceive water as unclean. At low (47.3%), middle (28.1%), and high elevations (29.2%), areas with higher perceptions of unclean water correlate with increased asthma prevalence (Fig. 8N). Asthma prevalence shows minimal variation with household smoking across elevations. At low (58.2%), middle (56.1%), and high elevations (55.6%) households with smoking members exhibit slightly higher asthma rates compared to non-smoking households (Fig. 8O). Asthma prevalence varies with households tobacco use across different elevations. Higher asthma rates are observed in household where tobacco is used: low elevation (72.7%), middle elevation (56.1%), and high elevation (62.5%), compared to households without tobacco use. Overall, tobacco use correlates with increased asthma prevalence (63.6%), underscoring its potential role in respiratory health outcomes (Fig. 8P).

Asthma prevalence by district and ethnicity

Supplementary_File_S1 (Table 2B) presents asthma prevalence data among Gujjar and Bakarwal individuals, categorized by district and ethnicity. Geographically, individuals living at high elevations exhibit the highest asthma prevalence, with Rajouri showing slightly higher rates than Poonch. Ethnic differences reveal that Gujjars consistently experience higher asthma prevalence than Bakarwals across all elevations, with the greatest disparity observed in the middle-altitude zone.

Demographically, asthma prevalence is higher among males in both districts, with a particularly pronounced gender gap in Rajouri. Married individuals exhibit significantly higher prevalence rates compared to singles, divorced, and widowed individuals, with widowed individuals in Poonch showing the highest rates. Age also plays a critical role, with individuals over 60 experiencing the highest asthma prevalence, particularly in Poonch. The 51–60 age group also shows elevated rates, reinforcing the trend of increasing prevalence with age.

Socioeconomic factors further highlight disparities in asthma prevalence. Individuals with no formal education are most affected, particularly in Poonch. Interestingly, in Rajouri, those with higher secondary education show a sharp increase in prevalence, though this trend declines among individuals with postgraduate education. Occupational patterns indicate that herdsmen experience the highest asthma prevalence, with smokers and tobacco users also displaying an elevated risk. Government employees and laborers report relatively high prevalence, especially in Poonch.

Income levels similarly reflect these patterns, with individuals earning less than ₹5,000 per month exhibiting the highest asthma prevalence, while those earning more than ₹10,000 show a slight reduction. Environmental factors also play a significant role, as traditional housing is associated with higher asthma prevalence compared to modern housing in both districts. The choice of heating system is another key factor, with traditional Bhukhari stoves significantly contributing to asthma risk, whereas individuals using electric heaters report lower prevalence. Additionally, kitchen location impacts asthma rates, with individuals cooking inside their homes experiencing higher prevalence compared to those using separate kitchens.

Binary logistic regression findings

Bivariate analyses were conducted to examine the associations between altitude and each explanatory variable in the overall sample (Supplementary_File_S1, Table 2A). Additionally, these analyses assessed the relationships between districts, ethnicity, and each variable within the Gujjar Bakarwal population (Supplementary_File_S1, Table 2B).

To evaluate the fit of the binary logistic regression model, we utilized two key metrics: the Hosmer-Lemeshow test and Pseudo R² values45. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test assesses the agreement between observed and predicted outcomes, where a p-value greater than 0.05 generally indicates a good model fit. Our test yielded a chi-square statistic of 1.680 with 8 degrees of freedom (p = 0.989), suggesting no significant difference between observed and predicted values, thereby confirming a strong model fit.

We further assessed model performance using Pseudo R² values (Table 4). Unlike traditional R² values in linear regression, Pseudo R² values measure how well the logistic regression model explains variability in the outcome. A value of 1 indicates a perfect fit, while values above 0.2 are generally considered acceptable46. We employed both Cox and Snell R² and Nagelkerke R² to evaluate model performance. The Nagelkerke R² value of 0.822 indicates that the model explains approximately 82.2% of the variability in the outcome variable, suggesting a strong fit. While in some social sciences a Nagelkerke R² above 0.2 is typically deemed acceptable, interpretation may vary depending on the study context (Table 4).

Asthma risk factors identified via BLRM

Table 5 presents the results of a multivariable binary logistic regression model (BLRM) examining the odds of asthma in relation to various factors among the Gujjar Bakarwal population. Two models were used to assess the relationship between independent variables and self-reported, physician-diagnosed asthma in the past year. Model I provides unadjusted odds ratios (ORs), reflecting the raw associations between independent variables and asthma. Model II adjusts for potential confounding effects, ensuring a more accurate estimation of each variable’s independent contribution. Confounding arises when an additional variable is linked to both the independent variable and the outcome, potentially biasing the observed associations. Model II accounts for this by adjusting for all variables, preventing inflation or distortion of effects. For instance, income and education often covary, and failing to adjust for one may exaggerate the influence of the other. Similarly, altitude-related effects may be mediated by behavioral factors such as heating methods. Adjusting for confounders thus provides more reliable estimates, which are essential for identifying effective interventions. Among the 816 surveyed households, 22.5% reported asthma episodes in the year preceding data collection.

Residents of Zone C had notably higher odds of asthma compared to those in Zone A (Crude Odds Ratio [COR]: 3.54, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.79–6.98, p < 0.001). However, after adjusting for other variables in Model II, this association lost statistical significance (Adjusted Odds Ratio [AOR]: 1.43, 95% CI 0.30–6.76, p = 0.648). Confidence intervals indicate the range within which the true odds ratio likely falls, with a 95% confidence level. Prior research suggests that regional variations in asthma prevalence may be attributed to environmental and socioeconomic factors [43]. Conversely, residents of Zone D exhibited significantly lower odds of asthma compared to Zone A, both before and after adjustment (COR: 0.34, 95% CI 0.19–0.63, p = 0.001; AOR: 0.10, 95% CI 0.02–0.42, p = 0.002).

Married individuals had significantly lower odds of asthma compared to single individuals (AOR: 0.03, 95% CI 0.01–0.17, p < 0.001), while widowed individuals similarly exhibited reduced odds. Although divorced individuals showed lower odds, this was not statistically significant.

Individuals from extended families had significantly higher odds of asthma compared to those from nuclear families (AOR: 8.80, 95% CI 1.77–43.61, p = 0.008). This may be due to increased exposure to environmental and behavioral risk factors in larger households. Previous studies suggest that greater household size is associated with elevated asthma risk due to higher exposure to indoor pollutants47.

Individuals aged 31–40 years had a markedly higher likelihood of developing asthma compared to the reference group (0–10 years) (AOR: 93.36, 95% CI 7.31–1192.77, p < 0.001). Similarly, participants aged 21–30 years also had significantly higher odds (AOR: 12.32, 95% CI 1.08–140.64, p = 0.043). Although the 41–50 and 61 + age groups also exhibited increased odds, these associations were not statistically significant. The 11–20 and 51–60 age groups showed no significant association with asthma after adjustment. These variations may reflect differing levels of exposure to risk factors and age-specific vulnerabilities, aligning with studies that highlight distinct asthma risk factors across different life stages48.

Also, individuals with no formal education were more likely to develop asthma compared to those with secondary education or higher. Employment status also influenced asthma risk; individuals in government jobs and farming had significantly lower odds compared to unemployed individuals. A clear trend of decreasing asthma risk was observed with increasing income levels, with those earning more than ₹20,000 per month experiencing significantly lower risk compared to those earning less than ₹5,000. These findings suggest that higher education and economic stability contribute to better healthcare access and healthier living conditions, aligning with research on the impact of socioeconomic status on asthma risk49.

Living in a modern house was associated with lower asthma prevalence compared to traditional houses. Similarly, the use of an electric heater instead of the traditional Bhukhari (a wood-burning stove) was linked to a decreased asthma risk. Households with kitchens separate from the main living space had lower asthma prevalence compared to those where kitchens were located indoors.

Despite being a traditional water source, natural spring water was associated with lower asthma risk compared to piped water, hand pumps, or surface water. This may be due to lower contamination levels in natural springs, whereas piped systems and surface water sources are more susceptible to microbial and seasonal pollution. These findings suggest that both modern infrastructure and access to clean water—whether traditional or modern - are essential for reducing asthma risk, aligning with evidence linking environmental hygiene to respiratory health50.

Both cigarette smoking and broader tobacco consumption (including bidi and hookah) were strongly linked to increased asthma risk compared to non-smokers and non-tobacco users, reinforcing existing research that identifies tobacco as a major risk factor for asthma51.

In Model II, after adjusting for all independent variables, the associations between ethnicity, gender, and drinking water cleanliness were no longer statistically significant. The overall analysis highlights that asthma prevalence among the Gujjar Bakarwal population is shaped by a combination of demographic, socioeconomic, environmental, and behavioral factors. Notably, socioeconomic conditions (education and income), housing characteristics, and water sources emerged as the most critical determinants of asthma risk. These findings underscore the broader role of social determinants in respiratory health and suggest that interventions targeting socioeconomic disparities and environmental conditions could be instrumental in reducing asthma prevalence47,48,49,50,51,52.

Spatial probability of asthma occurrence

We utilized the odds ratio (OR) values of potential determinants to identify spatial risk factors for asthma. Equation (2) was applied to estimate the probability (pi) at each village, as illustrated in Fig. 9. This figure depicts the local epidemic risk levels across different zones in the Poonch and Rajouri districts. A reference threshold of p = 0.5 was established based on the segmentation criteria in the Binary Logistic Regression Model (BLRM) to determine the likelihood of asthma occurrence in each area. Here, a p-value exceeding 0.5 signifies an elevated asthma risk due to the combined effects of various risk factors, with higher values indicating greater vulnerability within the study area. Conversely, a p-value below 0.5 suggests a lower risk, indicating a relatively safer environment regarding asthma prevalence.

The results indicate that the highest asthma risk areas within Poonch and Rajouri districts are primarily concentrated in high-altitude regions (1,143–4,627 m) on the eastern side. In contrast, lower-altitude areas (560–1,358 m) on the western side of the districts exhibit comparatively lower asthma risk. Mid-altitude areas (1,359–2,188 m) display moderate asthma prevalence, highlighting a clear correlation between elevation and asthma risk distribution. This altitude-related pattern may be influenced by environmental factors such as air quality, temperature variations, and healthcare accessibility, which differ with elevation.

To assess asthma risk, the probability map was reclassified into five risk zones—extremely low, very low, low, medium, and high—using the Natural Breaks method combined with Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) interpolation (Table 6). Approximately 69.5% of the study area falls into the extremely low-risk category, while the very low, low, and medium probability zones account for 4.9%, 5.5%, and 6.1% of the area, respectively. The high-risk zone covers 13.8% of the study area, validating the effectiveness of the classification approach used in the probability map. In total, these zones span an area of 4,304 km².

The performance of the BLRM was assessed using a confusion matrix. In this evaluation, the model accurately classified 632 individuals without asthma and 184 individuals as having asthma. Specifically, the model correctly identified 77.6% of non-asthmatic individuals and 22.6% of asthmatic individuals.

Overall, the BLRM achieved a 94.2% accuracy rate indicating that the model correctly classified almost all cases. Additionally, the Kappa index, an important measure of model reliability, indicated 83.2% agreement beyond what would be expected by chance alone53. Thus, two performance metrics suggest that the model performs well in predicting asthma status (see Table 7). The high accuracy rate supports its overall effectiveness, while the robust Kappa index highlights that the model’s predictions are not merely coincidental.

Discussion

Our investigation into asthma prevalence among the Gujjar Bakarwal tribe in the high-altitude Himalayas reveals a significant public health concern, with a self-reported asthma prevalence of 22.5% over the past year. This study highlights the complex interplay of environmental, socioeconomic, and behavioral factors contributing to the elevated asthma risk in this population. Notably, asthma prevalence is higher among males (56.0%) than females (44.0%), suggesting that both biological and social determinants are at play. Additionally, significant variations in asthma prevalence across altitudinal zones emphasize the role of environmental factors such as air quality, allergens, and altitude-related respiratory stress.

Socioeconomic disparities, particularly income levels, further influence the asthma burden in this community. Lower-income households face an increased risk due to limited access to healthcare, medications, and preventive measures, compounded by poor housing conditions, including inadequate ventilation, mold, and indoor smoke from traditional heating methods like the Bhukhari. Economic constraints also correlate with higher exposure to occupational hazards, such as livestock herding and firewood collection, as well as lower health literacy, all of which impair effective asthma management17,18. These findings align with global evidence linking poverty to increased respiratory morbidity.

However, our study also indicates a higher asthma prevalence in higher-income households, which may be attributed to shifting lifestyles within the Gujjar Bakarwal community. Increased government employment and settlement in urban or semi-urban areas may contribute to changing dietary patterns, greater exposure to pollution, and indoor allergens from processed foods, vehicular emissions, and modern housing materials. Additionally, better healthcare access in higher-income groups may result in higher diagnosis rates, reflecting surveillance bias rather than a true increase in disease burden. These evolving socioeconomic and occupational transitions warrant further investigation to better understand the association between income and asthma risk.

Our findings align with global studies reporting a higher asthma prevalence among males, often linked to behavioral differences such as higher smoking rates and greater exposure to outdoor work environments9,12. The cold, dry air at higher altitudes, combined with increased exposure to allergens, supports previous research linking altitude to worsened respiratory health16,54. Cultural practices among the Gujjar Bakarwal, including tobacco use and outdoor occupations, may further exacerbate this gender disparity, emphasizing the need for gender-specific public health interventions.

Living in joint family settings was also associated with higher asthma prevalence (AOR: 8.80, 95% CI 1.77–43.61, p = 0.008), suggesting that overcrowding and exposure to indoor air pollutants, such as smoke from traditional heating methods like the Bhukhari and Chullah, are significant contributors. Many homes in these communities lack proper ventilation, intensifying exposure to respiratory irritants such as particulate matter and smoke. Studies have shown that overcrowded households with poor ventilation are linked to higher asthma rates, particularly in rural and semi-nomadic populations47. For the Gujjar Bakarwal, temporary housing structures with inadequate ventilation likely increase respiratory risks due to prolonged exposure to indoor pollutants. Addressing these factors through public health strategies, such as promoting improved ventilation and better housing designs, could help reduce asthma prevalence.

The use of surface water as a primary drinking source was also associated with higher asthma rates, potentially due to contaminants or pollutants in untreated water sources, as noted in other studies on respiratory health in rural and semi-nomadic communities55. Specific pollutants, such as heavy metals (e.g., lead and arsenic), biological contaminants (e.g., bacteria and viruses), and industrial runoff, have been detected in the region’s water sources and are known to exacerbate respiratory conditions. Exposure to these pollutants through drinking water may worsen asthma symptoms, particularly in vulnerable populations like the Gujjar Bakarwal. This finding is consistent with emerging evidence on water quality’s systemic health impacts. For example, arsenic contamination in groundwater has been linked to systemic inflammation and respiratory dysfunction in Bangladesh56while microbial pathogens in untreated water can exacerbate airway hyperreactivity57. Kumar and Ram (2017) similarly reported a 1.7-fold higher asthma risk among Indian households relying on hand pumps, likely due to agricultural runoff contaminating groundwater55. Additionally, damp conditions from storing untreated water in poorly ventilated homes may promote mold growth, a known asthma trigger58. Given the presence of industrial and agricultural pollution in surface water sources in our study area, strengthening water quality management and ensuring access to clean drinking water could help mitigate respiratory health risks.

The semi-nomadic lifestyle of the Gujjar Bakarwal also plays a crucial role in asthma risk, as seasonal migrations between low and high altitudes expose individuals to varying environmental conditions that influence respiratory health. During winter migrations to lower altitudes, households experience prolonged indoor exposure to Bhukhari smoke in poorly ventilated dwellings, supporting our findings on heating-related risks. Conversely, summer migrations to high-altitude pastures may reduce exposure to particulate matter but introduce cold-air triggers, aligning with our observed altitude-related risk patterns and established associations between cold, dry air and bronchoconstriction59. The transition between different altitudes, along with fluctuating exposure to allergens and pollution, likely exacerbates respiratory issues. Similar studies on high-altitude populations have demonstrated that migration patterns influence respiratory health due to changes in air quality and temperature47.

Limitations and future directions

This study has certain limitations. A primary limitation is the lack of clinical verification for asthma diagnoses, which may affect the accuracy of reported prevalence. The reliance on self-reported, physician-diagnosed asthma may also lead to underreporting, as undiagnosed cases were excluded - a concern particularly relevant in resource-limited settings with restricted healthcare access. Additionally, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causal relationships between asthma and its associated factors. Future research using longitudinal designs would provide deeper insights into the temporal links between environmental exposures and asthma onset or progression.

Another limitation is the study’s limited examination of seasonal migration patterns and their impact on asthma symptoms. Understanding whether lower-altitude environments during specific seasons offer any protective effects requires further investigation. Additionally, genetic predispositions to asthma within this population remain underexplored. Future studies should assess hereditary factors to gain a more comprehensive understanding of respiratory health risks among the Gujjar Bakarwal.

Among the factors influencing asthma risk, the most significant modifiable predictors were the use of traditional wood-burning Bhukhari stoves and reliance on contaminated water sources. While extended family structures and age-related vulnerabilities were also strongly associated with asthma, these are less amenable to immediate intervention due to cultural and biological constraints. Given resource limitations, policymakers should prioritize replacing Bhukhari stoves with electric heaters and improving access to clean water—such as natural springs or treated piped systems—to achieve the most substantial reductions in asthma prevalence. Notably, Bhukhari stoves are used in 95.1% of households, exposing residents to persistent respiratory irritants. Likewise, households relying on surface water or hand pumps face a 3.7–9.0-fold higher asthma risk compared to those using spring water. These findings emphasize the importance of modern infrastructure, such as improved housing and heating systems, in mitigating asthma risk.

Additionally, while indoor air pollution proxies, -such as Bhukhari use - were assessed, direct measurements of air pollutants (e.g., PM2.5, CO) were not conducted. This limitation restricts our ability to quantify exposure levels and establish dose-response relationships, a common gap in asthma research in similar settings.

Finally, the study’s findings should be interpreted with caution due to the wide confidence intervals observed in the adjusted odds ratios (AORs) for asthma in the 21–30 and 31–40 age groups, likely due to small subgroup sample sizes. Further research with larger sample sizes is necessary to confirm these associations and improve the robustness of the findings.

Public health recommendations

To address the health challenges faced by this community, public health interventions must be both culturally sensitive and feasible. The promotion of cleaner cooking and heating technologies, such as portable, low-emission stoves, could significantly reduce indoor air pollution. Given the nomadic lifestyle of the Gujjar Bakarwal, mobile health units that provide seasonal care, particularly respiratory health services, could bridge gaps in healthcare access. Furthermore, public health campaigns focused on reducing tobacco use, improving sanitation of water sources, and educating the community about the risks associated with traditional heating methods should be prioritized.

Conclusion

This study reveals a significant burden of asthma among the Gujjar Bakarwal tribe in the high-altitude regions of Rajouri and Poonch districts. We identified a complex interplay of demographic, socio-economic, environmental, and behavioral factors influencing asthma prevalence. Our findings align with previous research in different populations regarding factors such as age and smoking, but also highlight unique aspects related to altitude. Significant correlations were found with altitude, demographic traits, socio-economic status, environmental conditions, and health behaviors. Gender disparities, age, indoor air quality, housing conditions, and socio-economic factors emerged as key predictors of asthma. These results underscore the need for targeted public health interventions addressing these factors. To optimize public health impact, decision-makers should prioritize two key interventions: (1) transitioning households from Bhukhari stoves to electric heating systems to reduce indoor air pollution, and (2) expanding access to clean water sources (e.g., spring water protection or water treatment programs). These measures address the most dominant and modifiable risk factors identified in this study, offering a pragmatic pathway to reduce asthma burden in this vulnerable population. Future research should further investigate the specific effects of altitude versus other environmental factors on asthma risk to develop effective, evidence-based strategies for asthma management in similar settings.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files: Supplementary_File_S1. Additional supplementary files (Supplementary_File_S2, Supplementary_File_S3, and Supplementary_File_S4) have been providing to the editor and reviewers for the purpose of review.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BLRM:

-

Binary logistic regression model

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- DEM:

-

Digital elevation model

- GIS:

-

Geographic information systems

- GPS:

-

Global positioning system

- HHS:

-

Household schedule

- IDW:

-

Inverse distance weighting

- IVs:

-

Independent variables

- INR:

-

Indian rupees

- ORs:

-

Odds ratios

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristics

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

References

Ehteshami-Afshar, S., FitzGerald, J. M., Doyle-Waters, M. M. & Sadatsafavi, M. The global economic burden of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. int. J. Tuberc Lung Dis. 20, 11–23 (2016).

Nunes, C., Pereira, A. M. & Morais-Almeida, M. Asthma costs and social impact. Asthma Res. Pract. 3, 1 (2017).

Lundbäck, B., Backman, H., Lötvall, J. & Rönmark, E. Is asthma prevalence still increasing? Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 10, 39–51 (2016).

Global Initiative for Asthma. GINA-Main-Report-2022-FINAL-22-07-01-WMS.Pdf. (2022). https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/GINA-Main-Report-2022-FINAL-22-07-01-WMS.pdf

Braman, S. S. The global burden of asthma. Chest 130, 4S–12S (2006).

Bukalasa, J. S. et al. Associations of residential exposure to agricultural pesticides with asthma prevalence in adolescence: The PIAMA birth cohort. Environ. Int. 121, 435–442 (2018).

Fuertes, E. et al. Associations between air pollution and pediatric eczema, rhinoconjunctivitis and asthma: A meta-analysis of European birth cohorts. Environ. Int. 136, 105474 (2020).

Olsson, D. et al. Early childhood exposure to ambient air pollution is associated with increased risk of paediatric asthma: An administrative cohort study from stockholm, Sweden. Environ. Int. 155, 106667 (2021).

Meghji, J. et al. Improving lung health in low-income and middle-income countries: From challenges to solutions. Lancet 397, 928–940 (2021).

Žavbi, M. et al. Polymorphisms and haplotypes of the chromosome locus 17q12-17q21.1 contribute to adult asthma susceptibility in Slovenian patients. Hum. Immunol. 77, 527–534 (2016).

World Health Organization. Asthma. World Health Organization (2024). https://www.who.int/news-room/facts-in-pictures/detail/asthma

Vos, T. et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. Lancet 388, 1545–1602 (2016).

Kharaba, Z. et al. An assessment of quality of life in patients with asthma through physical, emotional, social, and occupational aspects. A cross-sectional study. Front. Public. Health 10, 883784 (2022).

Bellou, V., Gogali, A. & Kostikas, K. Asthma and Tobacco Smoking. JPM 12, 1231 (2022).

Tiotiu, A. I. et al. Impact of air pollution on asthma outcomes. IJERPH 17, 6212 (2020).

Jaakkola, J. J. K. & Jaakkola, M. S. Effects of environmental tobacco smoke on the respiratory health of children. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 28(Suppl 2), 71–83 (2002).

Bacon, S. L., Bouchard, A., Loucks, E. B. & Lavoie, K. L. Individual-level socioeconomic status is associated with worse asthma morbidity in patients with asthma. Respir Res. 10, 125 (2009).

Cardet, J. C. et al. Income is an independent risk factor for worse asthma outcomes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 141, 754–760e3 (2018).

Da Cunha, S. S., Pujades-Rodriguez, M., Barreto, M. L., Genser, B. & Rodrigues, L. C. Ecological study of socio-economic indicators and prevalence of asthma in schoolchildren in urban Brazil. BMC Public. Health. 7, 205 (2007).

Kinghorn, B. et al. Socioeconomic and environmental risk factors for pediatric asthma in an American Indian community. Acad. Pediatr. 19, 631–637 (2019).

Chen, Y., Bishop, M. & Liepold, H. Increased effect of obesity on asthma in adults with low household income. J. Asthma 47, 263–268 (2010).

Bhadrecha, P., Kumar, V. & Kumar, M. Medicinal plant growing under Sub-optimal conditions in trans-Himalaya region at high altitude. Def. Life Sc Jl 2, 37 (2017).

Cogo, A., Fischer, R. & Schoene, R. Respiratory diseases and high altitude. High. Alt. Med. Biol. 5, 435–444 (2004).

Huismans, H. K., Douma, W. R., Kerstjens, H. A. M. & Renkema, T. E. J. Asthma in patients climbing to high and extreme altitudes in the Tibetan everest region. J. Asthma 47, 614–619 (2010).

Van Veelen, M. et al. Emergency care for High-Altitude trekking and climbing. High. Alt. Med. Biol. ham20240065 https://doi.org/10.1089/ham.2024.0065 (2024).

To, T. et al. Global asthma prevalence in adults: Findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC Public. Health 12, 204 (2012).

Arokiasamy, P., Karthick, K. & Pradhan, J. Environmental risk factors and prevalence of asthma, tuberculosis and jaundice in India. IJENVH 1, 221 (2007).

Patel, S., Ram, U., Ram, F. & Patel, S. K. Socioeconomic and demographic predictors of high blood pressure, diabetes, asthma and heart disease among adults engaged in various occupations: Evidence from India. J. Biosoc Sci. 52, 629–649 (2020).

Aggarwal, A. N. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for bronchial asthma in Indian adults: A multicentre study. Indian J. Chest Dis. Allied Sci. 48, 13–22 (2006).

Ahmed, A., Kheraj, Mohammadi, A. & Bergquist, R. Hybrid GIS-MCDM approach for Hospital site selection suitability analysis in Poonch District, Jammu and Kashmir, India. GeoJournal 89, 186 (2024).

Ahmed, A., Kheraj, K., Ali, A., Rani, K. & Meenaxy, M. Geographical distribution of healthcare facilities in Poonch district: An evaluationthrough GIS. J. Mountain Res. 19 (2024).

Ahmed, A., Kheraj, K., Ali, A., Rani, K. & Meenaxy, M. Transhumance and the impact of development on the Gujjar-Bakarwal tribe: anethnographic study of cultural perceptions and Land-use changes. J. Mountain Res. 18 (2023).

Doody, O. & Noonan, M. Preparing and conducting interviews to collect data. Nurse Res. 20, 28–32 (2013).

Van Den Broeck, J., Argeseanu Cunningham, S., Eeckels, R. & Herbst, K. Data cleaning: Detecting, diagnosing, and editing data abnormalities. PLoS Med. 2, e267 (2005).

Zandbergen, P. A. Accuracy of iPhone locations: A comparison of assisted GPS, WiFi and cellular positioning. Trans. GIS. 13, 5–25 (2009).

Li, J. & Heap, A. D. A review of comparative studies of spatial interpolation methods in environmental sciences: Performance and impact factors. Ecol. Inf. 6, 228–241 (2011).

Kraak, M. J. & Ormeling, F. Cartography: Visualization of Geospatial Data 4th edn (CRC Press, Boca Raton; London, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429464195.

Lohr, S. L. Sampling: Design and Analysis (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429298899

Uakarn, C., Chaokromthong, K. & Sintao, N. Sample size estimation using Yamane and Cochran and Krejcie and Morgan and Green formulas and cohen statistical power analysis by G*power and comparisons.

Ziegel, E. R., Groves, R. M. & Couper, M. P. Nonresponse in household interview surveys. Technometrics 41, 381 (1999).

Kraak, M. J. & Ormeling, F. Cartography: Visualization of Spatial Data (Guilford Press, 2011).

Bertolini, G., D’Amico, R., Nardi, D., Tinazzi, A. & Apolone, G. One model, several results: The paradox of the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for the logistic regression model. J. Epidemiol. Biostat 5, 251–253 (2000).

Cox, D. R. & Snell, E. J. Analysis of Binary Data (Chapman and Hall, London, 1989).

Nagelkerke, N. J. A note on a general definition of the coefficient of determination. Biometrika 78, 691–692 (1991).

Cox, D. R. Analysis of Binary Data 2nd edn (CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 2018).

Clark, W. A. V. & Hosking, P. L. Statistical Methods for Geographers (J. Miley, 1986).

Vardoulakis, S. et al. Indoor exposure to selected air pollutants in the home environment: A systematic review. IJERPH 17, 8972 (2020).

Silverman, R. A. & Ito, K. Age-related association of fine particles and Ozone with severe acute asthma in new York City. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 125, 367–373e5 (2010).

Curtis, L. M., Wolf, M. S., Weiss, K. B. & Grammer, L. C. The impact of health literacy and socioeconomic status on asthma disparities. J. Asthma 49, 178–183 (2012).

Gan, W. Q., Sanderson, W. T., Browning, S. R. & Mannino, D. M. Different types of housing and respiratory health outcomes. Prev. Med. Rep. 7, 124–129 (2017).

Accordini, S. et al. A three-generation study on the association of tobacco smoking with asthma. Int. J. Epidemiol. 47, 1106–1117 (2018).

Mallol, J. et al. Regional variation in asthma symptom prevalence in Latin American children. J. Asthma 47, 644–650 (2010).

Congalton, R. G. & Green, K. Assessing the Accuracy of Remotely Sensed Data: Principles and Practices, 3rd edn (CRC Press, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429052729.

Del-Río-Navarro, B. E. et al. Global asthma network phase I study in mexico: Prevalence of asthma symptoms, risk factors and altitude associations—a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. Resp. Res. 7, e000658 (2020).

Kumar, P. & Ram, U. Patterns, factors associated and morbidity burden of asthma in India. PLoS ONE. 12, e0185938 (2017).

Smith, A. H., Lingas, E. O. & Rahman, M. Contamination of drinking-water by arsenic in bangladesh: A public health emergency. Bull. World Health Organ. 78, 1093–1103 (2000).

Wright, R. J. Moving towards making social toxins mainstream in children’s environmental health. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 21, 222–229 (2009).

Jaakkola, J. J. K., Hwang, B. F. & Jaakkola, M. S. Home dampness and molds as determinants of allergic rhinitis in childhood: A 6-year, population-based cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 172, 451–459 (2010).

D’Amato, G. et al. Meteorological conditions, climate change, new emerging factors, and asthma and related allergic disorders. A statement of the world allergy organization. World Allergy Organ. J. 8, 25 (2015).

Mathur, R. National Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical and Health Research Involving Human Articipants. (2017).

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere gratitude to the Gujjar Bakarwal community and all the interviewees for their invaluable participation and contributions to this study.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A. Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft; K. Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—editing; J.R. Writing—editing; A.M. Methodology, Writing—editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study did not undergo formal ethics review. In accordance with the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) National Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical and Health Research Involving Human Participants (2017)60ethics approval was not required for non-interventional, observational studies of this nature. The study complied with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from all participants following standard practices.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, A., Kheraj, Rocha, J. et al. Asthma prevalence and risk factors in Poonch and Rajouri districts, India: an epidemiological and geospatial analysis. Sci Rep 15, 23014 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07482-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07482-9