Abstract

With the rapid development of new energy vehicle technology, electric drive systems play a crucial role in the modern automotive industry. Ensuring the efficient and stable operation as well as reliability of electric drive systems has become a critical task. In order to prevent serious faults in the short-term leading to potential accidents, this paper proposes an innovative approach for embedding the Token Merging (ToMe) algorithm into the Vision Transformer (ViT), called the VToMe algorithm and combining it with the Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU) network to form the VToMe-BiGRU architecture for electric drive system fault prediction. Specifically, the VToMe algorithm achieves stable detection of medium to long term system faults, while the BiGRU network achieves rapid fault prediction in the short term. The VToMe-BiGRU is an intelligent analysis method applied to automobile workshops, which is closer to the data source for data processing and analysis, alleviates the strong dependence on real-time network transmission, reduces the time consuming and labor-intensive process of manually extracting and analyzing the features, and improves the accuracy and reliability of the fault prediction. The optimized VToMe-BiGRU algorithm combines the Transformer model and the BiGRU network, which effectively captures the critical features in the electric drive system data, thus improving the fault prediction performance. Experimental validation on real-world electric vehicle (EV) maintenance datasets demonstrates outstanding performance of the proposed method. The multi-class fault classification achieves an average accuracy of 93.49% with a 32\(\times\)32 patch size, outperforming state-of-the-art ViT++ by 0.12% while enhancing inference speed by 28% (32 FPS vs. 25 FPS for ViT++) to balance high precision and real-time efficiency. The short-term prediction yields a root-mean-square error (RMSE) as low as 6.33 and an accuracy (ACC) of 74.7% for complex fault modes such as bearing inner ring fault, surpassing traditional GRU/RNN models by over 20% in prediction accuracy. Moreover, the VToMe algorithm reduces computational complexity by 25% through hierarchical token merging, enabling efficient processing of high-dimensional sensor data without performance degradation. This research establishes a robust framework for real-time diagnosis of EV drive systems, effectively detecting critical faults like battery over-discharge and motor encoder errors with minimized false positives (FP < 5%), enhancing system reliability, reducing maintenance costs, and supporting proactive safety measures in EV applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electric drive systems play an indispensable role in the field of new energy vehicles. In order to ensure the efficient and stable operation and reliability of electric drive systems, fault prediction has become a crucial task1. The popularization of electric vehicles and the growing market demand make the performance and reliability of electric drive systems particularly critical. However, electric drive systems may face a variety of potential faults and problems in actual operation, which not only affect vehicle performance but also lead to safety hazards and increased maintenance costs2. Therefore, realizing accurate prediction and timely diagnosis of electric drive system faults so that preventive and maintenance measures can be taken is of great significance in safeguarding the reliability and user satisfaction of electric vehicles3.

The electric drive system includes key components such as the electric motor, battery pack, and electronic control unit, which work together in a coordinated manner to realize drive, energy conversion, and power output4. However, electric drive systems face various potential faults and problems during actual operation, such as battery aging, motor fault, and electronic component fault, which may lead to vehicle performance degradation, increased energy consumption, and driving safety hazards5. Therefore, accurately predicting potential faults and problems of the electric drive system and taking timely preventive and maintenance measures have become an important part of ensuring the efficient operation of electric vehicles and passenger safety6. In order to achieve accurate prediction of electric drive system faults, traditional rule-based and statistic-based methods are gradually no longer adapted to the complex and changing electric vehicle environment7.

With the development of artificial intelligence, deep learning and big data technologies, data-driven fault prediction methods based on data have gradually become a hot spot in research8,9. Using a large amount of real-time sensor data, vehicle state information and driving behavior data, combined with advanced machine learning algorithms, we can better capture the characteristics and patterns of potential faults in electric drive systems, and achieve more accurate prediction and early warning10. Token Merging (ToMe) achieves this by a lightweight matching algorithm that progressively merges similar tokens within the Vision Transformer (ViT), realizing a significant loss of performance without basically increase the throughput of the ViT architecture11. The ViT algorithm has advantages in processing image data to better capture key features in electric drive system data12, while the Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU) algorithm can effectively model time-series data to capture the evolution of fault modes13.

In this context, this paper aims to explore an innovative approach to incorporate the ToMe algorithm into ViT and combine it with the BiGRU algorithm for fault prediction and simulation of electric drive systems. By combining these advanced techniques, we expect to provide useful solutions for stability and reliability improvement of electric vehicles. The main contributions of this paper can be summarized as:

-

1.

We develop a novel architecture for fault diagnosis of electric drive systems under multiple operating states. The architecture integrates discrete numerical and image data processing techniques by converting fault data into image and vector formats.

-

2.

We propose the VToMe algorithm, an innovation that significantly optimizes the image Block-to-Token transformation process and enhances the self-attention mechanism. The proposed VToMe algorithm not only improves the token representation to capture image features more efficiently and integrate global information but also improves the processing efficiency and classification accuracy of the model in various visual tasks.

-

3.

We combine the powerful VToMe algorithm with the BiGRU model for effective data processing, which enables efficient fault prediction. This method not only enhances the flexibility and continuity of data processing but also significantly improves the prediction accuracy and computational performance of the system, providing comprehensive data support for complex fault diagnosis.

The rest of this article can be organized as follows: Section 2 reviews the current research status of fault prediction for electric drive systems. Section 3 proposes the fault prediction system architecture and the key algorithm (VToMe-BiGRU). The experimental results and the analysis process are described in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 draws the conclusions and future work.

Related work

In recent years, scholars have actively carried out research related to the fault prediction of new energy vehicle electric drive systems, mainly focusing on the following aspects.

-

1.

Current research has made progress in fault diagnosis and intelligent recognition methods for electric drive systems14, such as rule-based expert systems, data and physically-based modeling, and hybrid methods. These methods have demonstrated application results in fault diagnosis of critical components of electric vehicles. However, these methods often rely on a large amount of fault data or accurate physical models and are not flexible and adaptable enough when facing unknown failure modes15. In contrast, our study improves the ability to recognize novel fault modes and the accuracy of intelligent recognition by analyzing the limitations of existing fault datasets and evaluation systems and introducing the VToMe-BiGRU algorithm.

-

2.

Time series analysis plays a crucial role in electric drive system fault diagnosis16,17, especially when dealing with long and short-term failure modes. Traditional real-time diagnostic methods applied to the in-vehicle environment are limited to transient data analysis, which makes fault prediction and diagnosis across time spans difficult. In the face of complex failure modes across brands or models, traditional methods show limitations in dealing with long-term data dependencies and short-term anomalous behaviors18. For this reason, this study introduces the VToMe-BiGRU algorithm, which combines the efficient data processing capability of the Token Merging technique and the long and short-term memory properties of BiGRU19, making it capable of capturing more detailed fault signals in time-series analysis20. With this approach, we are able to perform fault diagnosis on different time scales, thus improving the accuracy and reliability of diagnosis. This innovative improvement not only optimizes the process of real-time fault diagnosis but also enhances the performance of the model in dealing with long- and short-term fault prediction, which significantly improves the efficiency and accuracy of fault diagnosis for electric drive systems21.

-

3.

Failure prediction for electric drive systems: Fault prediction in electric drive systems identifies potential faults by monitoring and analyzing critical components in real-time22,23. Although existing methods build prediction models by collecting and analyzing battery temperature, current24, and voltage data, they have limitations in adapting to new failure modes and rapidly changing environmental conditions25. By combining the VToMe-BiGRU algorithm, our work not only improves the accuracy of fault prediction but also enhances the model’s ability to adapt to new environments and failure modes26,27, thus improving the reliability and maintenance efficiency of electric vehicles.

-

4.

Fault simulation of electric drive systems: Fault simulation research is crucial in the field of electric drive systems28,29. Current research has focused on simulation and diagnostic methods for automotive engines, power electronics, and drive systems, as well as the simulation of vehicle electronic control systems and electric drive systems30. Although these studies provide support for fault prediction, diagnosis, and repair strategies, they often lack comprehensive consideration of complex system interactions and realistic fault conditions31,32. Our study optimizes the simulation model by introducing the VToMe-BiGRU algorithm, which improves the comprehensiveness and accuracy of fault diagnosis and provides a stronger guarantee for the reliability of electric vehicle systems.

-

5.

Research on ToMe Algorithm: The ToMe algorithm effectively reduces the computational complexity32 and improves the processing speed by simplifying the operation of the attention mechanism in the Vision Transformer model33,34. Although existing research has achieved significant results in tasks such as image classification35 and target detection, the application potential of the ToMe algorithm has not been fully explored in the field of fault diagnosis of electric drive systems36. In this paper, the ToMe algorithm is applied to the fault diagnosis of electric drive systems, demonstrating its superior performance in real-time fault identification and processing, especially its high efficiency and accuracy when dealing with large-scale data and complex tasks.

-

6.

BiGRU Algorithm: The BiGRU algorithm has been widely used in the fields of natural language processing and speech recognition in particular, due to its excellent performance in time-series data analysis22,23. However, the potential of BiGRU has not been fully utilized in the field of electric drive system fault prediction24. In this study, we effectively improve the accuracy and timeliness of fault diagnosis by applying BiGRU algorithms to fault prediction in electric drive systems. Our work demonstrates a new application of the BiGRU algorithm in fault prediction of electric drive systems, which enhances the performance and adaptability of fault diagnosis models6,24.

This study focuses on the correlation between fault diagnosis and maintenance costs of electric drive systems. By integrating multi-dimensional maintenance cost elements such as labor, materials and downtime losses, a quantitative correlation model between system operating parameters and costs is constructed. Based on historical maintenance data and real-time monitoring parameters, the prediction method proposed in the study can effectively estimate future maintenance needs and cost distribution, providing data support for enterprises to optimize maintenance timing and reduce unnecessary downtime losses in production scheduling.

In model construction, by minimizing the overall reconstruction error of the system state, the study improves the identification accuracy of potential faults, provides a theoretical basis for preventive maintenance strategies, and thus reduces high-order maintenance costs caused by fault deterioration. In addition, the cost evaluation framework proposed in the study (such as Equation 7) systematically quantifies maintenance costs from the dimensions of fault probability and repair cost, providing methodological support for decision makers to balance reliability and economy, scientifically allocate maintenance resources, and formulate dynamic maintenance strategies. The research results are expected to improve the economy and reliability of system operation in practical industrial applications, and have significant engineering practice value and theoretical reference significance.

Proposed method

This section is mainly about two parts, the first part is the explanation of the general architecture diagram of the electric drive system fault prediction. The second part proposes the VToMe-BiGRU algorithm for the fault prediction of the electric drive system. Through the research of this paper, we aim to provide more advanced fault prediction methods for the electric vehicle industry and contribute to the promotion and development of new energy vehicles.

System architecture design

The flow of the algorithm for electric drive system fault prediction, as depicted in Fig.1, is a sophisticated process comprising three primary modules: the ViT+ToMe algorithm, BiGRU, and Health Monitoring. Each module plays a distinct yet interconnected role in ensuring accurate fault prediction and system health assessment. The input system full-state data is sourced from the electric drive feedback system of a new-energy vehicle, encompassing a rich array of sensor-derived information. This data includes critical parameters such as voltage, current, rotational speed, and temperature, all of which are essential for comprehensively understanding the operational status of the electric drive system. For the first path (ViT+ToMe), the process begins with converting discrete numerical data into graphical data. This transformation is achieved through a specialized mapping technique that translates time-series numerical values (e.g., voltage fluctuations over time, current variations) into a visual format. For instance, a sequence of numerical values representing motor performance over time might be converted into a grayscale or color-coded image, where each pixel’s intensity or color corresponds to a specific numerical value. These graphical images are then encoded into multiple patches. These patches serve as inputs to the ViT+ToMe model. The model leverages its advanced architecture, which includes self-attention mechanisms, to extract intricate features from these patches. By analyzing these features, the ViT+ToMe model realizes the monitoring of fault types. For example, it can identify whether a voltage-related anomaly corresponds to a specific type of electrical fault, such as a short-circuit or over-voltage condition.

The second path (BiGRU) involves feeding discrete numerical data into the BiGRU model in the form of a time series. BiGRU, with its bidirectional gated recurrent unit structure, is well-suited for processing time-series data. It captures both forward and backward temporal dependencies within the data. As the time-series data (e.g., a sequence of rotational speed values over time) is input into the BiGRU model, it processes each time step, updating its internal states. By analyzing these state transitions, the BiGRU model enables the prediction of both the time and type of fault occurrence. For example, it might predict that a gradual increase in motor temperature, as indicated by the time-series temperature data, will lead to a thermal fault within a specific timeframe. The Health Monitoring module acts as a central integrator. It receives the results from the BiGRU fault prediction (which includes the estimated time and potential type of fault) and the fault state classification from the ViT+ToMe model. This module employs a set of predefined rules and algorithms to synthesize these results. For instance, if the ViT+ToMe model classifies a fault as a severe electrical issue and the BiGRU model predicts its occurrence in the near future, the Health Monitoring module will prioritize this information. It then feeds the judgment results back to the Feedback Monitoring Results system. This system serves as the final output interface of the algorithmic system diagnosis, providing a comprehensive assessment of the electric drive system’s health.

To sum up, the Health Monitoring and Feedback Monitoring Results modules work in tandem to comprehensively judge the health stability of the electric drive system of new-energy vehicles. The former integrates and analyzes the outputs from the two fault-analysis paths, while the latter communicates these findings in a meaningful way, enabling timely interventions and maintenance actions to ensure the reliable operation of the electric drive system.

Datasets

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method in fault detection for electric drive systems, we focused on nine specific fault types: Motor Encoder Error (MEE), Battery Over-discharge (BOD), Battery Pack Voltage Fault (BPVF), Motor Gear Scratch (MGS), Motor Startup Speed Abnormal (MSSA), Speed Sensor Fault (SSF), Hub Motor Speed Abnormal (HMSA), Gearbox GearWear Fault (GGF), and Bearing Inner Ring Fault (BIRF). We categorized these faults into three priority levels (High, Medium, Low) based on their failure impact and probability of occurrence, which served as the control group in the experiment, as demonstrated in Table 1.

Figure 2 shows the architecture of fault diagnosis of electric vehicle drive system. The architecture is divided into four modules. Module 1 is the fault component, which covers 9 common fault components of electric vehicle drive system and obtains data through continuous data acquisition and analog-to-digital conversion (ADC). Module 2 is the fault tree, which is subdivided into motor component failure (MEE, MGS, MSSA, HMSA), power battery failure (BOD, BPVF) and other component failure (SSF, GGF, BIRF). Module 3 is the big data platform, which is used to store the data collected by module 2. Module 4 is data analysis and fault diagnosis. The data is first enhanced and then the fault diagnosis of electric vehicle drive system is performed. The overall architecture clearly presents the process from fault component data acquisition to final fault diagnosis.

Figure 3 shows the real-time fault diagnosis and data processing process of the electric vehicle drive system. The left side shows the status data curves of multiple fault components (MEE, BOD, BPVF, etc.) in different time periods. t1 to t2 are equal time intervals extracted from the collected data set. Through the time series data search box (Bbox), all electric drive status data from t2 to t3 can be obtained. The middle part is a schematic diagram of the retrieval of data for this time period. The right side is a visual display of fault data and real-time fault diagnosis results, which can intuitively present the system status (such as SYSTEM FAILURE), helping to understand the data processing, display and fault judgment methods in real-time fault diagnosis.

Proposed ViT+ToMe algorithm

The ViT algorithm, an image classification model grounded in the attention mechanism, has achieved remarkable results in numerous image related tasks. However, while it performs admirably on public-competition datasets, its performance on the dataset in this paper was suboptimal. Consequently, this paper employs the ViT+ToMe algorithm, based on the ViT++ algorithm. ViT+ToMe is formed by fusing the ViT++ algorithm with the Token algorithm, where the Transformer Block algorithm module in ViT++ is optimized into a “Transformer Block + Token Merging” module.

The ToMe algorithm is ingeniously designed, using a generic and lightweight matching algorithm to gradually merge similar tokens within the Transformer. This significantly enhances the throughput of state-of-the-art models like the ViT-L model (size of 512) and ViT-H models (size of 518) by a factor of 2 without retraining. For example, it boosts the ViT-L model’s image - processing throughput by 2.2 times, with only a 0.19% - 0.29% accuracy reduction. It also improves training speed by a factor of 2 in video MAE fine-tuning, doubles ViT-B’s audio throughput with a mere 0.4% mAP reduction, and merges object parts into a single token even across multiple video frames, proving highly competitive in accuracy and speed for images, video, and audio.

As depicted in Fig. 4, the model intercepts nine types of numerical data at equal time intervals and uses the MATPLOT library to synthesize hybrid waveform plots as input data for detecting nine fault types: Motor Encoder Error (MEE), Battery Over-discharge (BOD), Battery Pack Voltage Fault (BPVF), Motor Gear Scratch (MGS), Motor Startup Speed Abnormal (MSSA), Speed Sensor Fault (SSF), Hub Motor Speed Abnormal (HMSA), Gearbox GearWear Fault (GGF), and Bearing Inner Ring Fault (BIRF). The input system full-state image undergoes “Linear Projection of Flattened Patches” to obtain patch embeddings, which enter the “Transformer Block + Token Merging” module. Part (a) illustrates gradual token merging in each block; part (b) reveals the module’s internal structure with Attention, ToMe, and MLP components. Part (c) demonstrates the “Bipartite Soft Matching” process: tokens are assigned to Set A or B, edges are drawn to the most similar tokens, the top \(r\) edges are kept, connected tokens are merged, and the sets are concatenated. After processing through multiple Transformer Encoder layers (\(L \times\)), each with MLP, Norm, and Multi-Head Attention, the embedded patches are fed into the MLP Head for classification. Finally, the model outputs classification results for the nine fault types, enabling precise electric-drive-system fault detection. This architecture effectively integrates the ViT+ToMe algorithm’s powerful feature-processing capabilities, leveraging ToMe’s token-merging and throughput-improvement advantages to handle input data and achieve accurate fault classification.

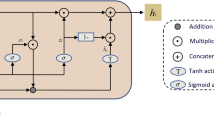

BiGRU algorithm

This subsection proposes a long and short term fault prediction scheme for BiGRU autoencoder with an attention mechanism and jump connections.

As shown in Fig. 5, the fault prediction model using BiGRU autoencoder scheme with attention mechanism and jump connections. Nine sets of discrete numerical type fault data in each identification cycle are converted into vectors and used as input to the BiGRU model. The BiGRU algorithm predicts and tracks the results of fault data (predictive processing, similarity matching.) In the proposed model, the red line represents the RNN-ED scheme23, and \(\varvec{H}_f\) and \(\varvec{H}_b\) denote the forward and reverse hidden state vectors, respectively. \(\varvec{O}_e\) is the output vector of the encoder BiGRU, and \(\varvec{Att}\) denotes the output of the attention layer, i.e., the weights of the different time steps. The \(\varvec{att-output}\) denotes the output vector of the encoder weighted by the attention vector. The model meticulously considers the complexity of fault prediction and effectively captures the key features of system faults, thus providing strong support for improving the prediction performance.

This approach is a direct extension of the BiRNN-ED format23. We choose BiGRU as the RNN units of the encoder and decoder. The BiGRU network consists of two sets of GRUs in different directions, which are capable of extracting the temporal correlation of the input time-series data in both forward and reverse directions. After the encoding is completed, the encoder hidden state vector \(\varvec{H}_e\) is used as the embedding vector for constructing \(\varvec{H}_I\). The output vector of encoder \(\varvec{O}_e\) is concatenated with the hidden state vector to form the input of the attention layer. The attention layer computes the weight vector \(\varvec{Att}\) at different time steps. The \(\varvec{Att}\) vector is then multiplied with the encoder output to obtain the \(\varvec{att-output}\) vector, which highlights the effect of critical time step information. In the decoding stage, the \(\varvec{att-output}\) is sent as an input vector to the decoder BiGRU. Furthermore, the \(\varvec{att-output}\) is connected to the decoder BiGRU output via a jump connection and then fed into the linear prediction layer to complement the feature information and alleviate the decoding burden of single embedding vectors.

Given a set of time series data \(\varvec{X}=\left[ x_1, x_2, x_3, \ldots \right] ^T\). Each \(x_i\) contains an \(\varvec{m}\)-dimensional sensor reading. Let the hidden node of BiGRU be h. The BiGRU unit of the encoder yields the encoder output vector and the final hidden state vector11,23:

where \(f_e(\cdot )\) denotes the abstraction function of the encoder BiGRU.

In the attention layer, we use \(\varvec{H}_e^{1 \times 2 h}\) and \(\varvec{O}_e^{t \times 2 h}\) to compute the attention weights. First, the first dimension of \(\varvec{H}_e^{1 \times 2 h}\) is copied \(\textit{t}\) times to align with the dimension of the \(\varvec{O}_e^{t \times 2 h}\) vector. Input \(\varvec{H}_e^{t \times 2 h}\) and \(\varvec{O}_e^{t \times 2 h}\) into the attention layer and compute the attention weight \(\varvec{Att}^{1 \times t}\) for each time step. Then multiply \(\varvec{A} \textit{\textbf{t t}}^{1 \times t}\) and \(\varvec{O}_e^{\varvec{t \times 2 h}}\) to get the \(\varvec{att-output}^{1 \times 2 h}\) vector, which highlights the time-step information of the key encoder. The \(\varvec{att-output}\) is sent to the decoder BiGRU unit, which computes the output vector and the hidden state as follows11,23:

Then, the \(\varvec{att-output}\) is connected to \(\varvec{O}_d\), input to the linear prediction layer, decoded as \(\varvec{x}_t\), and repeated \(\textit{t}\) times to predict all encoded inputs \(\varvec{X}\). The reconstruction error at the \(\varvec{i}\) th moment is \(\varvec{e}_i=\varvec{x}_i^{\prime }-\varvec{x}_i\). Therefore, the proposed model is trained to minimize the overall reconstruction error \(\varvec{E}\):

where \(\left\| e_i\right\| _1\) is the 1-norm operator, which converges faster and models more robust than the 2-norm operator. Once the proposed model is well trained, the final encoder hidden state \(\varvec{H}_e\) can be considered as a compressed representation of the input \(\varvec{x}\). If the proposed model consists of multiple BiGRU layers, the embedding vector is obtained by concatenating the final hidden states of all the layers:

where \(\varvec{H}_e^L\) is the final implied state vector of the L th layer, \(\varvec{z}_t\) is the embedding vector of the input time series data, and L is the total number of BiGRU layers.

Evaluation indicators

After inputting the training data and test data into the BiGRU model, and conducting a series of calculations, we are able to obtain the degree of similarity matching for the final prediction of faults, as shown in Fig. 3. In order to obtain a quantitative standard for evaluation, we used two common metrics to evaluate the model prediction performance on the dataset, namely root mean square error (RMSE) and accuracy (ACC).

RMSE is one of the most commonly used metrics for regression evaluation, which can intuitively estimate the model’s prediction effect on the target value. It can be defined as follows:

where \(\varvec{R} \hat{\varvec{U}} \varvec{L}_i, \varvec{R} U \varvec{L}_i\) denotes the estimated RUL value and the actual RUL value, \(e_i\) denotes the model prediction error, n is the number of experimental rounds unit.

The accuracy measure evaluates the percentage of the model within the correct prediction range. The predicted value is considered reasonable when the prediction error is within the range of -13 and 10, \(e_i \in [-12,11]\). It can be calculated as

where \(\operatorname {Cor}\left( \varvec{e}_i\right) =1\) if \(e_i \in [-12,11]\), otherwise \(\operatorname {Cor}\left( e_i\right) =0\). In addition, false positive (FP) predictive values are defined when \(e_i<-12\), and false negative (FN) predictive values are defined when \(e_i>11\).

To sum up, accuracy is the most intuitive performance measure of a classifier’s effectiveness, representing the proportion of true results, both true positives (TP) and true negatives (TN), false positives (FP), false negatives (FN), in the total number of samples examined. It effectively combines the measures of correctly identified positives and negatives. Precision is a measure of the accuracy of positive predictions made by the classifier. It is the ratio of true positive predictions to the total number of positive predictions made. Moreover,the recall rate reflects the ability of the model to identify all positive cases within the medium term and can be calculated as

and the F1 score is a commonly used metric for measuring the accuracy of classification models, particularly important when dealing with imbalanced class data. It is the harmonic mean of precision and recall and can be calculated as

When conducting fault prediction based on our model, there are usually differences in the short-term, medium-term, and long-term indicators for different fault types. This is mainly caused by the differences in the characteristics of the faults themselves, the laws of data change, and the degree of impact on the system.

Short-term indicators

ACC: Take the battery over-discharge (BOD) and motor starting speed abnormality (MSSA) faults in the electric vehicle drive system as examples. The BOD fault develops rapidly. Once it occurs, the battery state changes significantly in a short time. Our model can accurately predict its occurrence in the short term based on parameters such as battery voltage and current. Therefore, the prediction accuracy may be relatively high. On the other hand, the MSSA fault may be affected by various complex factors, such as the environmental temperature and load changes during motor startup. These factors increase the prediction difficulty, resulting in a relatively lower short-term prediction accuracy of the model for the MSSA fault.

RMSE: For the bearing inner-ring fault (BIRF), in the initial stage of the fault, the changes in parameters such as vibration and temperature caused by it are relatively stable, and the short-term data fluctuations are small. The error between the model’s predicted value and the real value is small, so the mean squared error is low. However, for the speed sensor fault (SSF), since the sensor fault may cause data mutation or loss, it is difficult for the model to accurately track the data changes. The deviation between the predicted value and the real value is large, resulting in a high short-term mean squared error.

Medium-term indicators

Recall: In the medium term, the gearbox gear wear fault (GGF) develops relatively slowly and has certain patterns. By monitoring parameters such as the gear wear degree and vibration frequency, our model can better capture the fault signals, and thus accurately identify most of the fault situations in the medium-term prediction, resulting in a high recall. However, for the motor encoder error (MEE), which is a highly random fault, it is difficult to predict through conventional parameters in the medium term. The model may miss some fault situations, leading to a low recall.

RMSE: For the battery pack voltage fault (BPVF), in the medium term, the change trend of the battery pack voltage is relatively stable. The model can make relatively accurate predictions based on historical data and the current state, resulting in a small mean absolute error. However, for the motor gear scratch (MGS) fault, the development of the gear scratch degree may be affected by various uncertain factors, such as sudden load changes and fluctuations in lubrication conditions. This makes the mean absolute error of the model’s prediction relatively large.

Long-term indicators

F1-Score: For some gradually developing faults, such as the bearing inner-ring fault (BIRF), as time goes by, the fault features become more and more obvious. Our model can both accurately identify the fault (high accuracy) and find out most of the fault situations (high recall) in the long-term prediction, thus obtaining a high F1-score. However, for some intermittently occurring faults, such as the speed sensor fault (SSF), due to the randomness of the fault occurrence, it is difficult for the model to ensure both high accuracy and high recall in the long-term prediction, resulting in a low F1-score.

RMSE: For a fault like the battery over-discharge (BOD), which has a significant impact on the system and a relatively clear development trend, our model can better grasp its development law in the long-term prediction. The deviation between the predicted value and the real value is small, resulting in a low root mean squared error. For some complex faults, such as the communication fault between the motor and the electronic control unit, which involves the coordinated operation of multiple components and has diverse fault causes and manifestations, it is difficult for the model to make accurate predictions, resulting in a high long-term root mean squared error.

Experimental results and analysis

Experimental settings

In this section, we verify the feasibility of the proposed scheme through experiments. The total number of epochs was set to 150, with an upper learning rate bound of \(1e^{-5}\) and a lower bound of \(1e^{-6}\). The learning rate decay factor lrf was set to 0.001, and the batch size was set to 16. The loss function chosen was cross-entropy, and the optimizer was configured with Adam. All experiments were performed on a computing platform equipped with 4*NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPUs. For low-priority faults, the VToMe-BiGRU model takes an average of 78 minutes for training, and it takes approximately 0.01 seconds to test a single sample. For medium-priority faults, the average training time is 63 minutes, and the average testing time for a single sample is 0.012 seconds. For high-priority faults, the average training time is 96 minutes, and the average testing time for a single sample is 0.015 seconds. The differences in training time mainly stem from the complexity of data and the number of samples for different fault types, while the differences in testing time are related to the processing complexity of different fault features by the model.

In practical applications, the performance of the algorithm is limited by hardware resources (such as GPU memory and CPU computing power) and data transfer speed. When processing large-scale data, insufficient GPU memory may cause model training to be interrupted. Data transfer delays can affect the timeliness of real-time fault prediction. In addition, the sensor data formats and collection frequencies of electric vehicles from different brands and models vary. This poses higher requirements for the data pre - processing and feature extraction stages of the model, and may affect the adaptability of the model to different vehicles and the prediction accuracy.

We test the performance of the proposed scheme on a deep learning server, and the experiments are divided into two parts. In the first part, comparative experimental validation of VGG-16, InceptionV3, ResNet-10, ViT++(\(14\times 14/16\times 16/32\times 32\)), VToMe (\(14\times 14/16\times 16/32\times 32\)) algorithms is conducted to verify the superiority of the proposed VToMe algorithm. The second part analyzes the comparative experiments of GRU, RNN, CNN-LSTM, and VToMe-BiGRU algorithms on the dataset of this paper. To control the variables that may affect the results during the experimental process and ensure the reliability and validity of the experiments, we set up a set of experimental environments. The specific configuration parameters of software and hardware are shown in Table 2.

Experimental analysis

VToMe experimental

The VToMe algorithm is the backbone neural network of the VToMe-BiGRU model proposed in this paper. We conducted large-scale data experiments on all the fault states of the 9 major types, and the experimental results are shown in Table 3. The first column of the Table 3 is the 9 types of models. The first row is the 9 types of faults, the average ACC, and the model inference rate (the number of data frames recognized by the model per unit of time frame per second (FPS)).

Table 3 showcases a full-state multi-model comparison experiment, evaluating various models across nine fault types: Motor Encoder Error (MEE), Battery Over-discharge (BOD), Battery Pack Voltage Fault (BPVF), Motor Gear Scratch (MGS), Motor Startup Speed Abnormal (MSSA), Speed Sensor Fault (SSF), Hub Motor Speed Abnormal (HMSA), Gearbox GearWear Fault (GGF), and Bearing Inner Ring Fault (BIRF). The evaluation hinges on metrics such as Average ACC (%), FPS, and F1-score. Traditional convolutional models VGG-16, InceptionV3, and ResNet-101 were pitted against Transformer-based models like (ViT++) with varying patch sizes and our VToMe models.

VGG-16, with an average accuracy of 72.88%, low FPS (9), and F1-score (0.7283), exhibited inefficiency and poor generalization. InceptionV3 (76.44% average ACC) and ResNet-101 (82.62% average ACC) performed better but still lagged. ResNet-101’s F1-score of 0.8258 was lower than Transformer-based models, underscoring its limitations. Among (ViT++) models, (ViT++) Patch = 14x14 achieved 92.21% average ACC (93.5% for MGS, 95.5% for MSSA). Increasing patch sizes to 16x16 (92.44% average ACC) and 32x32 (93.37% average ACC) improved accuracy but reduced FPS (26 and 25, respectively), reflecting a speed-accuracy trade-off. Our VToMe models excelled. VToMe Patch = 14x14(Our) attained 92.52% average ACC, 37 FPS (highest), and 0.9248 F1-score, balancing speed and accuracy. VToMe Patch = 16x16(Our) (92.7% average ACC, 34 FPS, 0.924 F1-score) and VToMe Patch=32x32(Our) (93.49% average ACC, 32 FPS, 0.9343 F1-score, the highest) demonstrated superior performance.

Comparing extremum values: Average ACC’s maximum (93.49% for VToMe 32x32) versus minimum (72.88% for VGG-16) showed a 20.61% gap. FPS’s maximum (37 for VToMe 14x14) versus minimum (8 for InceptionV3), and F1-score’s maximum (0.9343) versus minimum (0.7283), all highlight VToMe’s dominance. This organized presentation clarifies each model’s performance in the algorithm’s context, emphasizing key findings and validating VToMe’s effectiveness.

3D Stereo visualization

Figure 6 shows the 3D stereo visualization of the data distribution for ACC. The X coordinate axis on the 3D graph is 9 types of faults, the Y coordinate axis is 9 neural network model algorithms, and the Z coordinate axis is ACC. The red dots indicate the ACC of one model on one fault. The blue dots indicate the projections of the red dots on the ACC and Model coordinate planes, which indicate the distribution of ACC for the full-state multi-model. The blue dots within the range of purple circles indicate the distribution of ACC values greater than 92% for the VToMe model. The blue dots within the range of yellow circles indicate the distribution of ACC values for the ViT++ model. The dots within the green circle indicate the performance results of the other algorithms. The models distributed in the lower left range have poorer results, and the distribution in the upper right range indicates better model performance results.

From the ACC and FPS data distribution of the full-state multi-model in Fig. 7, the purple circle range indicates that the ACC and FPS exhibit a waxing and waning phenomenon in the VToMe model. We can conclude that the improvements of FPS are at the cost of lower ACC. The specific application of the process should be based on the practical scenario to select a balance point between ACC and FPS.

VToMe-BiGRU experimental

The next experiment completed the short-term prediction of fault data on multiple models. The comparison experiments for short-term prediction on full-state multi-model are shown in Table 4. The data visualization and analysis in Table 4 is divided into: RMSE and ACC under multi-model prediction, as shown in Fig. 6; distribution of RMSE under multi-model prediction in 3D space shown in Fig. 7; distribution of ACC under multi-model prediction in 3D space shown in Fig. 8. From the experiments, it can be seen that the use of GRU, RNN, LSTM, and CNN alone often fails to achieve the expected results. Considering that the experimental data dimensions of this research are more diverse and long span, therefore, this paper proposes a comprehensive approach for fault diagnosis using the integration of ViT, Token Merging, and BiGRU.

The first column of Table 4 shows the multiple models, the second column shows the evaluation metrics RMSE and ACC, and the first row shows the various fault types. From the RMSE metrics data, it can be seen that the GRU model has larger errors in predicting the whole state, and the prediction accuracy is also lower than that of the traditional models (RNN, CNN-LSTM). Moreover, The proposed VToMe-BiGRU model outperforms other models in terms of RMSE and ACC. Meanwhile, in the curves of RMSE and ACC predicted by multiple models in Fig. 8, the prediction performance of the proposed VToMe-BiGRU shows superior performance, with RMSE lower than 10 and ACC accuracy higher than 70% under full-state prediction. VToMe-BiGRU model has slight changes in RMSE and ACC with different Patch sizes, but overall average ACC is higher and RMSE is lower.

As shown in Fig. 9, the blue dots on the projection plane formed by the coordinate RMSE and the coordinate Model are the 3D distribution of the model’s error over the full state. The green circle is the error distribution predicted by the GRU and RNN models, the yellow circle is the error distribution predicted by the CNN-LSTM model, and the purple circle is the error distribution predicted by the VToMe-BiGRU model. The lower right region of the projection plane is the region with the smallest error, i.e., the region of the predicted error distribution of VToMe-BiGRU model. Similarly, the upper right region of the projection plane in Fig. 10 is the region with the most accurate, i.e., the region of the predicted accuracy distribution of VToMe-BiGRU model.

From the above results of analyzing the experimental data, we draw the following conclusions

-

1.

The traditional image classification methods mainly rely on CNN, while the ViT algorithm converts image data into sequence data by introducing the Transformer model, and utilizes the self-attention mechanism to learn the multi-dimensional feature data that changes over time, which can achieve better results.

-

2.

Integrating the ToMe algorithm based on the ViT algorithm makes the model significantly improve the inference speed FPS.

-

3.

The VToMe-BiGRU algorithm, which combines ViT, ToMe, and BiGRU algorithms, is superior to the traditional algorithms in terms of inference speed, long and short-term prediction, and detection, and it is more effective in the analysis of multidimensional features.

The above results are attributed to the fact that the proposed VToMe-BiGRU algorithm converts discrete numerical types of data into two types of data, namely vectors and images, and undergoes multiple models for identification and prediction, which greatly reduces the probability of erroneous diagnosis.

Conclusion

In this paper, we propose a novel VToMe-BiGRU algorithm based on multiple input types of data to accurately predict long-term and short-term faults in power transmission systems. We are dedicated to solving the pivotal problem of electric drive system fault prediction to ensure its efficient and stable operation in the modern automotive industry. Specifically, the VToMe algorithm is constructed by combining the ToMe algorithm with ViT, and fused with the BiGRU algorithm to form the VToMe-BiGRU architecture, which provides an innovative approach for fault prediction in electric drive systems. The performance of multiple models in predicting nine types of faults in electric vehicle drive systems was compared. As can be gleaned from the data, when predicting the Motor Encoder Error (MEE) fault, the ACC of the VToMe Patch = 14\(\times\)14 (Our) model is 91.0%, which is higher than that of traditional models such as VGG - 16 (78.5%) and InceptionV3 (78.8%). The average ACC of the VToMe Patch = 32\(\times\)32 (Our) model reaches 93.49%, far surpassing 72.88% of VGG - 16. Moreover, its F1 - score is 0.9343, demonstrating excellent performance. Meanwhile, the VToMe model can strike a good balance between the FPS while enhancing the ACC. For instance, the VToMe Patch = 14\(\times\)14 (Our) model has an ACC of 92.52% and an FPS of 37. In contrast, when the (ViT++) series of models increase the Patch size to boost the ACC, the FPS will decline. These quantitative data reveal that the VToMe model has distinct advantages in terms of fault classification accuracy, the balance between speed and accuracy, and comprehensive performance.

Although the current model has achieved good results on computing platforms, it still faces challenges when applied to resource-constrained edge devices. We plan to use model compression techniques such as pruning and quantization to reduce the number of model parameters and computational load, making the model more suitable for edge devices. At the same time, we will optimize the deployment architecture of the model on edge devices to improve data processing speed and response efficiency, and achieve more efficient real-time fault prediction to meet the requirements of electric vehicles in actual operation scenarios. Improving the cross-model generalization ability is also a key focus of subsequent research. Currently, the model performs well on specific datasets, but its generalization ability needs to be enhanced when dealing with the drive system data of electric vehicles from different brands and models. In the future, we will collect more datasets from different sources, conduct cross-model training and testing, explore more effective feature extraction and transfer learning methods, enhance the model’s adaptability to different data distributions, ensure stable and accurate fault prediction in diverse industrial scenarios, and promote the wide application of this technology across the entire electric vehicle industry.

Data availability

The source data and codes presented in this article are not readily available because of the commercially sensitive data involved. Requests to access the source data and codes should be directed to fangxiaofen@ieee.org.

References

Yi, S., Li, C. & Li, Q. A survey of fog computing: concepts, applications and issues. In Proceedings of the 2015 workshop on mobile big data, 37–42 (2015).

Agarwal, S. et al. Volley: Automated data placement for geo-distributed cloud services. In NSDI (2010).

Basta, A., Kellerer, W., Hoffmann, M., Morper, H. J. & Hoffmann, K. Applying nfv and sdn to lte mobile core gateways, the functions placement problem. In Proceedings of the 4th workshop on All things cellular: operations, applications, & challenges, 33–38 (2014).

CV, N. A. & Lavanya, R. Fog computing and its role in the internet of things. In Advancing Consumer-Centric Fog Computing Architectures, 63–71 (IGI Global, 2019).

Kraemer, F. A., Braten, A. E., Tamkittikhun, N. & Palma, D. Fog computing in healthcare-a review and discussion. IEEE Access 5, 9206–9222 (2017).

Niu, D., Yu, M., Sun, L., Gao, T. & Wang, K. Short-term multi-energy load forecasting for integrated energy systems based on cnn-bigru optimized by attention mechanism. Applied Energy 313, 118801 (2022).

Bolya, D. et al. Token merging: Your vit but faster. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.09461 (2022).

Bolya, D. & Hoffman, J. Token merging for fast stable diffusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 4599–4603 (2023).

Zhu, H., Zhan, J., Lam, C.-T., Chen, B. & Ng, B. K. Machine learning based blind signal detection for ambient backscatter communication systems. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive Communications and Networking 11, 1172–1183 (2024).

Shao, W. et al. Dynamic token normalization improves vision transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.02624 (2021).

Dong, X. et al. Cswin transformer: A general vision transformer backbone with cross-shaped windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 12124–12134 (2022).

Fan, H. et al. Multiscale vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 6824–6835 (2021).

Roska, T. & Chua, L. O. The cnn universal machine: an analogic array computer. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Analog and Digital Signal Processing 40, 163–173 (1993).

Sharif Razavian, A., Azizpour, H., Sullivan, J. & Carlsson, S. Cnn features off-the-shelf: an astounding baseline for recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 806–813 (2014).

Wang, J., Yu, L.-C., Lai, K. R. & Zhang, X. Dimensional sentiment analysis using a regional cnn-lstm model. In Proceedings of the 54th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics (volume 2: Short papers), 225–230 (2016).

Livieris, I. E., Pintelas, E. & Pintelas, P. A cnn-lstm model for gold price time-series forecasting. Neural computing and applications 32, 17351–17360 (2020).

Lu, W., Li, J., Li, Y., Sun, A. & Wang, J. A cnn-lstm-based model to forecast stock prices. Complexity 2020, 6622927 (2020).

Kim, T.-Y. & Cho, S.-B. Predicting residential energy consumption using cnn-lstm neural networks. Energy 182, 72–81 (2019).

Wang, J., Yu, L.-C., Lai, K. R. & Zhang, X. Dimensional sentiment analysis using a regional cnn-lstm model. In Proceedings of the 54th annual meeting of the association for computational linguistics (volume 2: Short papers), 225–230 (2016).

Liu, S., Zhang, C. & Ma, J. Cnn-lstm neural network model for quantitative strategy analysis in stock markets. In Neural Information Processing: 24th International Conference, ICONIP 2017, Guangzhou, China, November 14-18, 2017, Proceedings, Part II 24, 198–206 (Springer, 2017).

Yan, R. et al. Multi-hour and multi-site air quality index forecasting in beijing using cnn, lstm, cnn-lstm, and spatiotemporal clustering. Expert Systems with Applications 169, 114513 (2021).

She, D. & Jia, M. A bigru method for remaining useful life prediction of machinery. Measurement 167, 108277 (2021).

Duan, Y., Li, H., He, M. & Zhao, D. A bigru autoencoder remaining useful life prediction scheme with attention mechanism and skip connection. IEEE Sensors Journal 21, 10905–10914 (2021).

Lin, X., Quan, Z., Wang, Z.-J., Huang, H. & Zeng, X. A novel molecular representation with bigru neural networks for learning atom. Briefings in bioinformatics 21, 2099–2111 (2020).

Zhu, H. et al. A space shift keying-based optimization scheme for secure communication in iiot. IEEE Systems Journal 17, 5261–5271 (2023).

Graham, B. et al. Levit: a vision transformer in convnet’s clothing for faster inference. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 12259–12269 (2021).

He, K. et al. Masked autoencoders are scalable vision learners. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 16000–16009 (2022).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

Marin, D. et al. Token pooling in vision transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.03860 (2021).

Han, J., Guo, J.-E., Cai, X., Lv, C. & Lev, B. An analysis on strategy evolution of research & development in cooperative innovation network of new energy vehicle within policy transition period. Omega 112, 102686 (2022).

Xu, Z. & Wu, Y. Environmental economic co-benefits and offsets effects of china’s unified energy-carbon market. Journal of Environmental Management 331, 117268 (2023).

Ahmann, L., Banning, M. & Lutz, C. Modeling rebound effects and counteracting policies for german industries. Ecological Economics 197, 107432 (2022).

Hua, Y. & Dong, F. How can new energy vehicles become qualified relays from the perspective of carbon neutralization? literature review and research prospect based on the citespace knowledge map. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 29, 55473–55491 (2022).

Wang, Y., Fan, R., Lin, J., Chen, F. & Qian, R. The effective subsidy policies for new energy vehicles considering both supply and demand sides and their influence mechanisms: An analytical perspective from the network-based evolutionary game. Journal of Environmental Management 325, 116483 (2023).

Ma, J. & Mayburov, I. The impact of taxation policies on the research and development of alternative fuel vehicle companies–a case study of nio inc. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, vol. 958, 012019 (IOP Publishing, 2021).

Chua, L. O. Cnn: A vision of complexity. International Journal of Bifurcation and Chaos 7, 2219–2425 (1997).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by Quzhou Science and Technology Key Research Project: Research on key technologies for Intelligent diagnosis and predictive maintenance of faults in new energy vehicle Integrated electric drive systems based on big data (2022K105); Research on intelligent detection methods for electromagnetic interference attacks in industrial IoT (2023K252); Research on intelligent visual networking platform for pump station clusters used in urban sewage lifting (2023K248), and in part by General Research Project of Zhejiang Provincial Department of Education: Research on intelligent fault diagnosis of rolling bearings based on deep learning(Y202456902).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z.; methodology, L.Z.; software, L.Z.; validation, L.Z. and X.F.; formal analysis, L.Z., X.F., and Z.K.; investigation, L.Z., X-F.F., and Z.K.; resources, L.Z., W.Z., and X.J.; data curation, L.Z. and X-F.F.; writing–original draft preparation, L.Z., W.Z., and X-F.F; writing–review and editing, L.Z. and X-F.F.; visualization, W.Z. and X-F.F.; supervision, W.Z. and X-F.F.; project administration, L.Z.; funding acquisition, L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, L., Fan, X., Kang, Z. et al. Long and short term fault prediction using the VToMe-BiGRU algorithm for electric drive systems. Sci Rep 15, 21478 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07546-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07546-w