Abstract

The increasing global incidence of cancer emphasizes the vital role of machine learning algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI) in identifying novel anticancer targets and developing new drugs. Computational approaches can significantly quicken research on complex disorders, enabling the discovery of effective treatments. This study explores anticancer targets by assessing the potential of naturally occurring compounds derived from various plants to cure colorectal cancer. Twenty compounds were sourced from PubChem, and the RPS20 protein structure was obtained from AlphaFold, and mutation “V50S” was added. Validation of mutated RPS20 protein was performed using the Ramachandran plot and ERRAT. Binding sites on the mutated RPS20 protein were identified with DeepSite, followed by virtual screening to pinpoint the most promising natural lead drug candidate. Indirubin emerged as the lead drug candidate, fulfilling all ADMET criteria and exhibiting a good binding affinity. Further development included designing an AI-based drug using the WADDAICA server, which was validated through molecular docking, molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, and MMGBSA. The electronic properties of indirubin were studied using DFT calculations. The results show a moderate HOMO-LUMO gap, indicating its potential reactivity and the possible capability for biological target interactions. These findings indicate that indirubin could serve as a potent and effective cancer inhibitor, offering high efficacy with minimal side effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer occurs when individual cells proliferate out of control and invade other bodily regions. The word “cancer” refers to a broad category of illnesses that can impact any tissue, organ or organ system in the body1. 20% of newly diagnosed cases of colorectal cancer had metastatic disease at presentation, and another 25% of patients with localized disease at diagnosis will go on to develop metastases2. In 2014, colorectal cancer (CRC) was estimated to have caused 8% of new cancer cases and 8–9% of all cancer deaths in the United States (US). It is the third most frequent malignancy in both men and women3. In the United States, the chances of getting invasive colorectal cancer (CRC) are 5% for men (1 in 20) and 4.6% for women (1 in 22) during a lifetime. The median age at diagnosis is approximately 70 years.

The incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) varies greatly throughout the world; in the US and Europe, it is ten times greater than in African and Asian nations4. An increased incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) is linked to the Western lifestyle, which includes established risk factors such as alcohol consumption, obesity, and red meat (beef and pork)5. Individuals who suffer from inflammatory bowel conditions, such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, are also at an increased risk of colorectal cancer and should be closely monitored6. 5% of colorectal cancer (CRC) cases are caused by hereditary disorders known to be linked to the disease’s development, such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and hereditary non-polyposis CRC (HNPCC). Another 20% of instances are thought to be related to familial clustering. The majority of CRC cases are sporadic (about 75%)7.

The stage of CRC affects both survival and cure rates. The three stages of tumor staging are determined by the size of the primary tumor (T stage), lymph node involvement (N stage), and the presence of distant metastases (M stage)8. Increasing the intake of whole grains, fruits, and vegetables tends to prevent sporadic colorectal cancer (CRC)9,10,11. It has been demonstrated that low-dose aspirin or other COX2 inhibitors can effectively prevent colorectal polyps12,13. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is treated differently in the early stages due to anatomical differences from other colon cancer types, and local recurrence is a significant cause of morbidity and poor quality of life14. The studies with 194 patients shared that the most common symptoms that occurred among patients of CRC were rectal bleeding (58%), abdominal pain (52%), and changes in bowel habits (51%)15,16.

RPS20, which encodes the ribosomal protein uS10, plays a crucial role in ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis through the maturation and assembly of ribosomal subunits17. Not necessarily confined to such roles, it was recently implicated in the different cancers associated with RPS20, particularly colorectal cancer (CRC). A truncating germline mutation (V50S) in RPS20 has been associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma, qualifying this gene as one of the possible cancer predisposition genes. It has also been shown that mutations in RPS20 affect pre-ribosomal RNA maturation and alter the gene expression profile changes associated with the possible development of cancer18. This makes RPS20 a significant candidate therapeutic target in CRC and justifies further exploration of its biological essentiality in cancer and treatment strategies, inspiring a new wave of research and potential breakthroughs in cancer treatment.

Colorectal cancer is caused by the type of mutation (insertion) in the RPS20 gene in the position of 50th valine replaced by serine19. Subsequently, there are some specific therapeutics and treatments that are still considered beneficial for treating colorectal cancer, but these drugs also leave a negative impact on the human body20,21. Chemotherapy, which is an adjuvant treatment, has the main advantages of combination treatment, including reduced drug toxicity and adverse effects as well as synergistic or additive efficacy. Current colorectal cancer (CRC) treatments, such as chemotherapy, often lead to a range of adverse effects that significantly impact patients’ quality of life. Chemotherapy-induced side effects include nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and severe immunosuppression, which make patients more susceptible to infections22. Additionally, chemotherapy drugs can cause organ toxicity, particularly affecting the heart, liver, and kidneys22. Patients may also experience long-term consequences, such as infertility, neuropathy, and a higher risk of developing secondary cancers due to the toxic nature of some treatments. These side effects not only diminish patients’ overall health but also significantly reduce their ability to maintain normal daily activities, underscoring the urgent need for alternative therapies with fewer negative impacts. Monoclonal antibodies and the antimetabolite 5-FU are utilized as primary treatments for colorectal cancer, targeting specific molecular pathways to inhibit cancer cell growth. Chemotherapy, which is often used as an adjuvant treatment, provides additional benefits by reducing drug toxicity and adverse effects. The main advantages of combination treatment include synergistic or additive efficacy, thereby enhancing the overall effectiveness of the therapy23. Panitumumab is a human monoclonal antibody against EGFR, and functions similarly to cetuximab24. All these drugs treat colorectal cancer but also cause toxicity in different organs and organ systems of the body.

The success rates of drug identification have increased due to the new proposal of artificial intelligence (AI) as a viable tool for learning and discovering pharmacological big data in drug discovery25. Artificial intelligence (AI) has been used to improve the efficacy of drug development, saving both time and money by reducing unnecessary synthesis and testing26,27,28. By leveraging AI tools, the process of forming effective drugs has become less challenging compared to the traditional drug design era29.

This research aims to develop a successful drug candidate by utilizing AI algorithms, involving multiple immunoinformatic tools. Both computer-aided drug design and plant-based medicines are regarded as useful resources for drug discovery and development. Plant’s phytochemicals possess anti-cancer properties and provide defense against pathogenic microorganisms30. Several fact-compounds have been intensively investigated for potential application in cancer treatment, as explained in the following study31. Phytochemicals have a large diversity of chemical structures and span a wide spectrum of medicinal purposes32. In this study, lead plant phytochemicals were redesigned with artificial intelligence to create a lead drug candidate.

Materials and methods

Receptor protein 3D structure retrieval and protein mutation

The 3D structure of the target protein was retrieved using the AlphaFold database (https://alphafold.com/), an AI-integrated resource powered by DeepMind AI and Google33. Specifically, the 3D structure of the target protein, “Small ribosomal subunit protein uS10,” was obtained using the AlphaFold ID: AF-P60866-F1-v4. The mutation V50S, associated with colorectal cancer, was introduced into the retrieved protein structure using the PyMOL Mutagenesis Wizard selecting the rotamer with minimal steric clash to preserve backbone geometry34.

Protein 3D structure validation

The validation of 3D structure obtained from AlphaFold was validated by procheck Ramachandran plot and ERRAT (https://saves.mbi.ucla.edu/). Ramachandran plot is widely used to check the torsion and angles of the amino acid residue in the three-dimensional plane to a two-dimensional plane35. The favored regions and disallowed regions were checked. To verify the 3D structure chain breaks and warnings, the ERRAT program was used to check the chain breaks in the 3D structure of the target protein36.

Binding site prediction of receptor protein

Identifying the binding site is crucial in drug design as it is where the small molecule (ligand) interacts with the receptor protein to form bonds. This site comprises active amino acid residues that facilitate binding interactions with the ligand. The binding site was predicted using DeepSite (https://open.playmolecule.org/), an AI tool, which identified the active pocket37.

Retrieval of phytochemicals 3D structure

Phytochemicals effective against cancer, identified from the literature, were retrieved from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)38,39. PubChem provides all necessary information and 3D structures of compounds determined by NMR technology. A total of 20 phytochemicals were retrieved from the PubChem database.

Screening of the phytochemicals by molecular Docking and ADME

Phytochemicals were screened based on their binding affinity with the receptor protein using AutoDock Vina40. The protein was uploaded into MGL tools, and polar hydrogens were added to protonate it. The protein PDBQT file was then generated, and the grid box was set at coordinates x: 0.0299, y: 0.5799, z: 11.7600. The phytochemical files were converted to PDBQT format with torsion angles of 6 or fewer. AutoDock Vina was run via the command prompt to predict the binding affinities of the phytochemicals. Additionally, SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php) was employed to evaluate the pharmacokinetic properties, including absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) of the phytochemicals41. This comprehensive analysis allowed for the identification of the lead drug candidate based on its favorable ADME profile, ensuring optimal drug-likeness, bioavailability, and minimal toxicity, which are critical for its potential therapeutic application.

Enhancement of natural compound with AI

The lead phytochemical with the best binding affinity was used to design the AI enhanced ligands using the AI server “Webserver-Aided Drug Design By Artificial Intelligence And Classical Algorithm” (WADDAICA) (https://heisenberg.ucam.edu:5000/)42,43.

Molecular Docking of AI enhanced ligands and molecular interactions analysis

AI enhanced ligands were docked using two popular docking tools AutoDock Vina and MOE (molecular operating environment)40,44. To this end, we used high-throughput virtual screening and docking simulations with an open-source AutoDock Vina tool. The designed AI enhanced ligands were prepared in PDBQT format and optimized for the binding sites of the target proteins. AutoDock Vina calculates the binding affinity between the ligand and the protein, which helps researchers understand the most likely (plausible) binding poses.

Docking and molecular dynamics simulations were performed using MOE (Molecular Operating Environment, a comprehensive software solution for molecular modeling and simulations). Ligands were optimized in geometry before docking, and receptor-ligand interactions were analyzed using the hierarchical MOE scoring functions. The docking procedure was based on conformational sampling, receptor flexibility and scoring to predict optimal binding modes and interactions of the AI enhanced ligands with the protein targets. Docking of the ligand and receptor with AutoDock Vina and MOE was performed to confirm the consistency and robustness of the ligand-receptor interaction predictions.

To analyze the molecular interactions of the lead AI enhnaced ligand, LigPlot+, PyMOL, and Discovery Studio were used. 2D and 3D molecular diagrams were generated to analyze the interactions, including bond types, bond angles, and the categories of amino acids involved with the ligand45,46,47.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation and MMGBSA analysis of receptor protein and AI enhanced lead

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation was conducted and MMGBSA (Molecular Mechanics Generalized Born Surface Area) was performed using the Desmond program developed by Schrödinger LLC48. The initial step was the docking of RPS20 and the AI enhanced lead to anticipate the fixed location of the chemical within the active region of the protein49. Subsequently, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted using Newton’s classical equation of motion to ascertain the ligand-binding state in a physiological setting throughout 100 nanoseconds50.

The ligand-receptor complex underwent preprocessing using Maestro’s Protein Preparation Wizard, which encompassed optimization, minimization, and rectification of any absent residues. The system configuration was established using the System Builder tool, utilizing the TIP3P solvent model in an orthorhombic box at a temperature of 300 K and a pressure of 1 atm. The OPLS_2005 force field was employed51. Counter ions and a solution of sodium chloride at a concentration of 0.15 M were included to neutralize the models, simulating internal body conditions. Before the simulation, a process of equilibration was carried out, during which snapshots of the trajectory were taken every 100 picoseconds for subsequent analysis.

The thermodynamic integration (TI) approach was employed to calculate the absolute binding free energy of the ligand-receptor complex. This entailed producing numerous intermediate states between the unbound and bound configurations of the AI enhanced lead, with each state being simulated individually. In our simulations, we employed a series of equally spaced lambda values ranging from 0.0 to 1.0 at intervals of 0.1, resulting in 11 discrete λ points: λ = 0.0, 0.1, 0.2, …, 0.9, 1.0.

The MMGBSA methodology, implemented through the use of Desmond, was employed to compute the binding free energy between RPS20 and the AI enhanced lead52. The approach described in this study integrates molecular mechanics with a generalized Born solvent model and surface area continuum solvation to calculate the binding free energy of the ligand-receptor complex (Zaheer et al., 2023). The total free binding energy was calculated by using the Eq. (1).

where dGbind = binding free energy, Gcomplex = free energy of the complex, Gprotein = free energy of the target protein, and Gligand = free energy of the ligand.

ADMET analysis

ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) is a crucial part of preclinical trials. To predict the ADME properties, SwissADME was utilized41. This tool predicted various pharmacokinetic properties, including lipophilicity, water solubility, and drug-likeness. Additionally, the oral toxicity of the lead AI enhanced lead was assessed using ProTox 3.053.

DFT analysis

Quantum chemistry DFT calculations were performed with the Gaussian 09 W software package to calculate the electronic properties of indirubin AI Enhanced Lead. The parameters of B3LYP functional were used to calculate the compound’s electronic properties, and the 6-31G’ basis set was used to calculate the optimized molecular geometry. We calculated the energy difference between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the compound, which will be termed the HOMO-LUMO energy gap in order to know the chemical reactivity and stability of the compound.

The HOMO-LUMO energy gap (ΔEgap) is calculated using the equation:

where: ΔELumo is the energy of the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital, and ΔEHomo is the energy of the highest occupied molecular orbital.

The electronic properties and reactivity of ligand molecules were essential in computational drug discovery DFT, analysis and understanding of the stability of the ligand-protein complex. The HOMO-LUMO gap can best determine any molecule’s chemical hardness or softness. The narrower the interval, the greater the likelihood of reactivity and biological interactions. Moreover, molecular electrostatic potential maps and dipole moment calculations were used for a comprehensive understanding of the electronic activities of ligands, aiding in more profound insights into probable binding affinity with target proteins.

Results

Target protein 3D structure

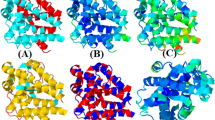

The target protein that was retrieved from AlphaFold has a good alignment graph Fig. 1. The confidence score of the protein structure was also excellent which was 90%. The V50S substitution was successfully modeled with minimal perturbation to the local backbone (Fig. 2).

Validation of the receptor protein 3D structure

The Ramachandran plot of the retrieved receptor protein has a Rama score of 100% with 92.3% amino acid residues in the most favorable region and 7.7% amino acid residues in the additional allowed region. None of the amino acid residues was in the disallowed region Fig. 3. The ERRAT score was also excellent (96.104), making it a good structure for further analysis (Fig. 4).

Binding site prediction of receptor protein

The binding site of the RPS20 was predicted to get the maximum binding affinity of the ligand with the receptor protein. One binding site was predicted and the coordination of the binding site was “x: 0.0299, y: 0.5799, z: 11.7600” with a score of “0.5499”. At these coordinates the amino acids are most active and interact maximum with the receptor protein. The binding site can be seen in Fig. 5.

Retrieval of phytochemicals 3D structure

The 22 phytochemicals having ant-cancerous activities that were retrieved from the PubChem can be seen in Table 1. The 3D structures were used in further analysis.

Virtual screening of phytochemicals

All phytochemicals that were retrieved were screened based on binding affinity. Table 2 contains the binding affinity of the phytochemicals with RPS20. The best ligand based upon binding affinity was vincristine lacks good molecular attraction and ADME properties. The best phytochemical according to the binding affinity was indirubin based on the molecular interaction, bonding types and met all in-silico ADMET criteria (drug‑likeness, low toxicity risk, and acceptable pharmacokinetics) so, indirubin was selected as the lead compound as it has good molecular interactions and AMDE properties as compared to vincristine and other higher affinity phytochemicals.

AI optimization of Indirubin

Indirubin was selected as the lead compound among the 20 phytochemicals. To enhance the drug− likeness properties and binding affinity of the indirubin. A total of 13 AI enhanced ligands of indirubin were designed by the AI web server Table 3.

Molecular docking of AI enhanced ligands and molecular interactions analysis

AutoDock Vina and MOE were utilized to evaluate the binding affinities and molecular interactions of the 31 AI enhanced ligands docked to the RPS20 protein. The two were used to obtain robust and reliable results. AI enhanced ligand 2 had the best predicted binding affinity out of the other ligands. AI enhanced ligand 2 displayed a binding energy value of − 6.7 KJ/mol with AutoDock Vina and MOE binding energy value of − 4.9942 KJ/mol. This agreement between the two docking methods further supports AI enhanced ligand 2 as the most promising candidate for follow-up studies. Along with the binding affinity, RSMD values were calculated to evaluate the structural stability of the AI Lead 2 during the docking. The RSMD for AI Lead 2 with AutoDock Vina was 0.00, which referred to the stable nature of the ligand docking into the receptor binding site during the docking simulation. The RSMD for the MOE was likewise 0.5727, with similar stability and fluctuation of the ligand in the protein’s active site. The best AI enhanced ligand was 2, based on the binding affinity, and has more affinity than its parent compound indirubin. The binding energies of the thirty-one AI enhanced ligands can be seen in Table 4.

The molecular interaction of the indirubin AI ligand 2 with RSP20 protein was good. Indirubin AI ligand formed one Conventional hydrogen bond, one Pi-Cation, one Pi-Sigma, and five Pi-Alkyl with bond angels of 2.34 Å, 4.88 Å, 3.76 Å, 4.65 Å, 5.14 Å, 5.33 Å, 4.03 Å and 5.04 Å respectively Table 5. The details of the bond types, bond angles, and amino acid residues are reported in Table. The 2D molecular interactions can be seen in Fig. 6. The 3D molecular interactions can be seen in Fig. 7.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation and MMGBSA analysis of receptor protein and AI enhanced lead

The molecular dynamics (MD) simulation results for the RPS20 indirubin AI enhanced lead complex reveal the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of both the receptor (RPS20) and the ligand (indirubin AI). The RMSD evolution plot indicates how the RMSD of the receptor fluctuates throughout the simulation, providing valuable insights into its structural conformation. In the RMSD graph, the left Y-axis represents the RMSD of the receptor, while the right Y-axis indicates the RMSD of the ligand. The RMSD plot for the receptor demonstrates the deviation of its structure from the reference frame backbone throughout the simulation. Notably, fluctuations of 1–3 Å are typically considered acceptable for small, globular proteins, as they indicate normal thermal fluctuations. Larger deviations could suggest significant conformational changes occurring during the simulation. Regarding the stability of the ligand, the Ligand RMSD plot, labeled ‘Lig fit Prot’, demonstrates the stability of indirubin AI within the receptor’s binding pocket. This RMSD is calculated after aligning the protein-ligand complex on the receptor backbone and measuring the deviation of the ligand’s heavy atoms. If the Ligand RMSD values exceed those of the receptor, it suggests potential diffusion of the ligand away from its initial binding site. In this case, the RMSD graph indicates that both the receptor and the ligand stabilize after approximately 65 nanoseconds into the simulation. This stabilization suggests that the interactions between RPS20 and indirubin AI have reached equilibrium, allowing for a more detailed analysis of the molecular dynamics Fig. 8.

The Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) analysis provides insights into localized changes occurring along the receptor chain during the protein-ligand molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. RMSF for each residue is calculated based on the trajectory time, reference time, positions of atoms in the residue, and their average square distance. Peaks in the RMSF plot highlight regions of the receptor that experience the highest fluctuations during the simulation. For the RSP20 receptor, the RMSF plot indicates that the initial 10 to 15 amino acids show notable fluctuations, followed by another significant fluctuation observed between amino acids 70 and 80 Fig. 9. These fluctuations are typical of regions within a protein that is more flexible or less structured compared to alpha helices and beta strands, which generally demonstrate more rigidity.

Root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis of the RSP20 receptor during the molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of the protein-ligand interaction with indirubin AI. Peaks in the plot indicate regions of pronounced fluctuation, with the initial 10–15 amino acids and residues 70–80 experiencing significant deviations.

The RMSD of the indirubin AI enhanced lead reveals overall stabilization, although a deviation is observed between 20 and 57 nanoseconds. This deviation is mirrored in the Radius of Gyration (rGyr) plot, which follows a similar pattern to the RMSD of the ligand, indicating changes in the compactness of the ligand structure during this period. Intramolecular hydrogen bonds (intraHB) were consistently formed throughout the 100-nanosecond simulation, indicating stable internal interactions within the ligand. The Molecular Surface Area (MolSA) remained consistent with the ligand’s RMSD, while the Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA) remained stable throughout the simulation, reflecting a consistent solvent exposure of the ligand. The Polar Surface Area (PSA) also displayed stability, showing a similar trend to the RMSD of the ligand, with only minor variations. All ligand properties can be seen in Fig. 10.

Properties of indirubin AI following the molecular dynamics simulation. The analysis highlights overall stable RMSD behavior, with some deviation observed between 20 and 57 nanoseconds, consistent ‘extendedness’ indicated by the Radius of Gyration (rGyr), formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds throughout the simulation, and stable molecular surface area (MolSA) properties.

The free energy calculation for the RSP20-Indirubin AI complex, as depicted in Fig. 11, shows the variation in binding free energy throughout the 100,000 picoseconds (100 ns) simulation. The graph illustrates a general trend of decreasing energy, starting from approximately − 500 kcal/mol and reaching more stable energy values around − 2000 kcal/mol as the simulation progresses. This indicates that the binding affinity between the receptor (RSP20) and the ligand (indirubin AI) strengthens over time.

Initially, the binding free energy fluctuates significantly, reflecting the system’s adaptation and the establishment of stable interactions between the receptor and ligand. The energy values stabilize after approximately 60,000 picoseconds, suggesting that the complex has reached a stable binding conformation. This stabilization phase is characterized by smaller fluctuations, indicating a consistent and energetically favorable interaction.

The negative values throughout the simulation, particularly those stabilizing around − 2000 kcal/mol, indicate a strong and favorable binding between RSP20 and indirubin AI. These results suggest that indirubin AI remains securely bound within the receptor’s binding pocket throughout the simulation, forming a stable complex that is energetically favorable. The decrease in binding energy over time is consistent with the ligand settling into an optimal binding conformation, further supporting the suitability of indirubin AI as a potential inhibitor or modulator of the RSP20 receptor.

Free energy calculation of the RPS20-indirubin AI complex over a 100,000 picosecond (100 ns) molecular dynamics simulation. The graph shows the binding free energy decreasing and stabilizing around − 2000 kcal/mol, indicating a strong and favorable interaction between the receptor and ligand as the simulation progresses.

The MMGBSA analysis, conducted after 100 nanoseconds of simulation for the RPS20-Indirubin AI interaction, provided a binding free energy of -42.48 kcal/mol at the start of the simulation (0 ns) and − 31.39 kcal/mol at the end of the simulation (100 ns). The negative values indicate favorable binding between RPS20 and indirubin AI, suggesting a stable and energetically favorable protein-ligand interaction. The decrease in binding free energy from the initial to the final time points might reflect subtle changes in the binding mode or conformational dynamics within the complex throughout the simulation.

Analysis of RMSD deviations over the period of 20 ns to 57 ns peaks by about 2–3 Å and fall into the acceptable range of approximately 1–3 Å for a globular protein, thereby reflecting normal conformational adaptation and not real instability. Beyond ~ 65 ns, the RMSDs for both the protein and the ligand was stable, which indicates that this RPS20-indirubin AI complex has reached equilibrium. The RMSF analysis indicates the peripheral loop regions (1–15 residues, 70–80) are largely fluctuating and not directly contributing to ligand binding; thus, the integrity of the binding pocket is intact. The other complementary parameters radius of gyration, solvent accessible surface area and molecular surface areas, polar surface area and intramolecular hydrogen bonds have also stabilized after 65 ns showing compactness and solvent exposure consistency of the complex. Finally, the gradual decrease in free energy MMGBSA of − 42.48 to − 31.39 over the 100 ns simulation indicates that indirubin AI adopts a thermodynamically favorable binding conformation, further evidence of the stability and robustness of this inhibitor-target interaction. These results imply that indirubin AI effectively occupies the binding pocket of RPS20, forming a stable complex throughout the simulation.

ADMET analysis

The ADMET properties of the indirubin AI enhanced lead were evaluated using SwissADME and Protox 3.0 to assess its potential as a candidate drug. The analysis covered various physiochemical and pharmacokinetic parameters, including molecular weight, hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, the number of rotatable bonds, blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration, gastrointestinal (GI) absorption, lipophilicity, solubility, drug-drug interaction, metabolism, synthetic accessibility, and permeability.

The AI-derived derivative of indirubin has a better ADME profile: its estimated lipophilicity (log P) increased from − 3.67 to -4.83, indicating more hydrophilicity and perhaps improved bioavailability. The other parameter that improved water solubility, which became “soluble” instead of “moderately soluble,” suggesting improved absorption/distribution in water-based biological environments. These adjustments, though modest, represent meaningful steps toward optimizing the compound’s pharmacokinetic properties. The AI enhanced lead exhibited favorable properties, successfully showing high gastrointestinal absorption. Importantly, there were no violations of Lipinski’s rule of five, indicating good drug-likeness and potential oral bioavailability. The detailed ADMET properties of the AI enhanced lead and comparison of AI lead with indirubin are summarized in Table 6.

The boiled egg model from SwissADME used to intuitively estimate brain penetration and passive gastrointestinal absorption, indicates that the AI enhanced lead was likely to penetrate both the BBB and the GI tract. The yellow region in the boiled egg diagram signifies a high probability of brain penetration, while the white region indicates a high probability of passive gastrointestinal absorption, as shown in Fig. 12.

ProTox 3.0 was employed to evaluate and compare the toxicity profiles of the AI-enhanced lead compound and indirubin. The AI-enhanced lead was predicted to have an LD50 of 2300 mg/kg, classifying it under toxicity class 5, which indicates a lower toxicity profile. In contrast, indirubin showed a lower LD50 of 1500 mg/kg, placing it in toxicity class 4, suggesting relatively higher toxicity. Additionally, the AI-enhanced lead proved superior average structural similarity (61.59%) and prediction accuracy (68.07%), compared to indirubin’s 42.12% similarity and 54.26% prediction accuracy.

Organ Toxicity of the AI-enhanced lead showed no strong activity for neurotoxicity or nephrotoxicity, while indirubin exhibited active neurotoxicity (0.72), indicating potential central nervous system concerns. Hepatotoxicity was active for both, with low probability scores (0.55 for AI-lead and 0.57 for indirubin), suggesting weak but present hepatic risk. Toxicity Endpoints of the AI-enhanced lead was predicted to be mutagenic (0.51) and non-carcinogenic, indirubin showed non-mutagenic (0.50) but active carcinogenicity (0.61), highlighting a potentially more serious long-term risk. Furthermore, indirubin exhibited active clinical toxicity, while the AI-lead did not.

Tox21 Nuclear Receptor and Stress Pathways showed both compounds activated the Aryl hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) and showed mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) disruption, a marker of cellular stress. However, the AI-enhanced lead was more selective in pathway activation, suggesting better specificity and fewer off-target effects. Molecular Initiating Events showed both compounds showed inactive binding across most neurological and endocrine receptors, with the exception of acetylcholinesterase (AChE), where both were active (0.55 and 0.57 respectively), indicating potential neuromodulator effects. Metabolic Enzyme Interaction of the AI-enhanced lead showed moderate interaction with CYP1A2 (0.72) and CYP2C9 (0.64), which were also predicted for indirubin, although with lower probability scores (0.53 and 0.52, respectively), suggesting better metabolic predictability for the AI-lead.

Both compounds exhibit some toxicity liabilities, the AI-enhanced lead demonstrates a more favorable toxicity profile overall, particularly in terms of lower predicted systemic toxicity, reduced neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity, and higher prediction confidence. These results support the potential of AI optimization in improving the drug-likeness and safety of natural scaffolds such as indirubin. A detailed summary of this comparative toxicity analysis is presented in Table 7.

DFT analysis of the AI lead

The calculated HOMO-LUMO energy gap of 0.13886 eV suggests moderate reactivity. Typically, a gap of < 0.1 eV indicates high chemical reactivity (low stability), a gap between 0.1 and 0.2 eV corresponds to moderate reactivity, and a gap > 0.2 eV suggests low reactivity (high stability). Therefore, the AI lead compound demonstrates a balanced reactivity profile, making it suitable for further optimization (Fig. 13). The AI enhanced lead, which balances stability and reactivity, has the potential to be a good starting point for further studies of biological interactions based on its energy gap. The moderate HOMO-LUMO gap indicates that the AI enhanced lead might be involved in electron transfer interactions with the target during the first stages of drug–target recognition, which might increase its pharmacological activity.

Discussion

Cancer remains a life-threatening disease characterized by abnormal gene expression patterns that lead to uncontrolled cell proliferation. Colorectal cancer (CRC), which affects the rectal region, is the third most common cancer worldwide and ranks fourth in cancer-related mortality54. The incidence of CRC has been rising steadily, particularly in Western countries, with risk factors such as regular consumption of red meat, alcohol intake, smoking, and obesity contributing to this increase. Men are more susceptible to these risk factors, which accounts for the higher prevalence of CRC among men compared to women55. Recent studies have identified germline mutations in the RPS20 gene, encoding ribosomal protein S20, as a potential contributor to hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma (CRC) without DNA mismatch repair deficiency56. These mutations disrupt pre-rRNA processing, leading to altered gene expression profiles that may contribute to tumorigenesis56. However, therapeutic strategies targeting RPS20 remain underexplored. Our approach leverages AI-enhanced natural compounds to inhibit RPS20, offering a novel avenue for CRC treatment. By focusing on natural compounds, our strategy aims to enhance specificity and reduce toxicity compared to traditional chemotherapeutic agents.

Previous research has shown that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are frequently used in treating CRC due to their ability to reduce chronic inflammation, a common characteristic of the disease57. Drugs such as Aspirin, Sulindac, and Atorvastatin have been found to reduce the risk of CRC by up to 50% and inhibit tumor growth. Specifically, while many NSAIDs are associated with gastrointestinal, renal, and hepatic side effects, our lead compound demonstrated no predicted nephrotoxicity or neurotoxicity, although hepatotoxicity and mutagenicity were marked as active. This suggests a partial improvement in the toxicity profile, but also highlights areas requiring further optimization58. Mutations in RPS20, encoding ribosomal protein uS10, have been linked to hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma (CRC), highlighting its role in colorectal cancer susceptibility. These mutations such as V50S disrupt pre-rRNA processing, leading to altered gene expression profiles that may contribute to tumorigenesis18. Therefore, there is an urgent need for more effective and safer therapeutic options, particularly those derived from natural sources that are compatible with human physiology. Recent advancements in AI offer promising tools for designing novel drug candidates with improved efficacy and safety profiles59.

RPS20 has been studied for its additional roles in tumor formation, mainly in connection with colorectal cancer (CRC)60. Mutations in RPS20 within people’s germline have been noted as a reason for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma, which adds to our knowledge about its role in CRC susceptibility18. RPS20 overexpression has also been detected in different cancers, especially in renal clear cell carcinoma (RCC), and it promotes tumor growth and metastasis by activating AKT-mTOR and ERK-MAPK signaling pathways60. Regardless of these results, scientists have mainly left out attempts to target RPS20. Mostly previous studies have focused on where and when silencing occurs, plus which pathways are activated, but not one focus on designing or finding special inhibitors. Although RPS20 has been found to link with both the p53-MDM2 axis and GNL1, such knowledge has not yet led to new cancer therapies60.

We resolve this gap by combining different computational tools to look for and make new small-molecule inhibitor that are active against RPS20. Virtual screening, molecular docking, and dynamic simulations showed that certain compounds strongly bind and are highly selective for the active sites of RPS2061. More specific techniques differ from widespread strategies, which might lead to unwanted results outside the desired pathways. The fact that our inhibitor (indirubin) inhibiting ribosomal proteins means it takes less risk of messing with normal protein production. Studies indicate that in-silico these compounds could successfully obstruct RPS20 signaling and slow down the progression of tumors62. In therapy, addressing RPS20 may give a new approach for CRC patients having RPS20 overexpression or changes. Homing in on precise molecular differences is our approach, which follows the rules of precision medicine to provide the greatest results with fewer harms43. Previously, scientists understood the part that RPS20 played in cancer biology, and we are the first to create inhibitor that target this protein. Such inhibitors show excellent specificity as well as efficacy, which sets the stage for treating colon cancer.

In our research, we employed Indirubin as a natural compound known for its anticancer property as a positive control to verify our computational study findings. Indirubin has been found effective in inducing apoptosis in various cancer cell lines, especially ovarian cancer cell lines, through mitochondrial mechanisms. With this, it was seen as a binding-interacting activity with the RPS20 protein63. Moreover, applications of AI in drug discovery have shown promise in improving the efficiency and efficacy for identifying possible therapeutic agents. For example, one of the subsidiaries of Alphabet-Isomorphic Labs, intends to initiate human trials of their first drug designed solely by AI before the end of the year as a showcase of the very promising role of AI in transforming drug development. Our approach follows this critical trend by demonstrating how AI may take natural compounds and turn them into high-potency molecules with favorable pharmacological profiles while drastically lowering toxicity64,65.

In this study, we aimed to develop a potent drug candidate against CRC by leveraging AI algorithms and plant-derived compounds. The target protein, “Small ribosomal subunit protein uS10,” was retrieved from the AlphaFold database and validated through the Ramachandran plot and ERRAT analysis, confirming its structural integrity. The binding sites of the target protein were identified using DeepSite, an AI tool that ensures strong ligand-protein interactions, a crucial step for effective drug design66. Based on an extensive literature review, we selected phytochemicals with documented anticancer properties and retrieved their structures from the PubChem database. Virtual screening using Autodock Vina was performed, and the top 20 phytochemicals were selected based on their binding affinities with the target protein.

Indirubin was identified as the lead compound due to its superior ADMET profile, favorable binding interactions, and molecular stability. To further enhance its drug-likeness, we designed AI enhanced ligand of indirubin using an AI server, which was then subjected to molecular dynamics (MD) docking studies with Autodock Vina and MOE. The molecular interaction analysis, conducted using LigPlot+, PyMOL, and Discovery Studio, revealed that indirubin forms one conventional hydrogen bond, one Pi-Cation, one Pi-Sigma, and five Pi-Alkyl interactions with the target protein, underscoring its strong binding affinity39.

To further validate the stability and interaction of indirubin with the RSP20 protein, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and MMGBSA analysis were performed using the Desmond. The simulation results indicated that both the protein and the ligand stabilized after approximately 65 nanoseconds, with the RMSD values demonstrating a steady-state interaction. The RMSF analysis highlighted minor fluctuations in certain regions of the protein, particularly within the first 10–15 amino acids and between amino acids 70 and 80, which correspond to less structured areas. Despite some deviations observed between 20 and 57 nanoseconds, indirubin remained stably bound within the protein’s binding pocket. The net energy calculations over the 100-nanosecond simulation showed a decrease and stabilization of binding energy, confirming the strong and stable interaction between indirubin and the RSP20 protein.

Finally, ADMET analysis confirmed that the AI-designed ligand of indirubin exhibited favorable pharmacokinetic properties, including successful passage through high gastrointestinal (GI) absorption. The compound also adhered to Lipinski’s rule of five, indicating good drug-likeness and potential oral bioavailability. With a moderate HOMO-LUMO gap 0.13886 eV, the AI lead compound may have enough energy to remain stable while retaining some chemical reactivity to be added to the global design compound. With this energy gap, AI can be involved in electron transfer interactions, an important mechanism for increasing drug efficacy.

These findings could augment previous studies, thus concluding the possibility of using AI-driven drug design to amplify natural compounds for therapeutic use. Docking and RSMD analysis of indirubin AI enhanced Lead showed strong binding affinity and stability, thus making indirubin AI enhanced Lead a promising candidate for further biological studies. Approaches similar to these in Naveed et al. (2023) and Sadia et al. (2024) demonstrate how the WADDAICA AI platform can be used to optimize natural compounds (in this case, gamma-tocotrienol, ascorbic acid, and curcumin) to enhance the efficacy and safety profiles of these compounds43,62. This research highlights how AI can optimize natural compounds into potent drug molecules with optimal pharmacological and low toxic properties. Thus, indirubin AI enhanced Lead serves as an example of how therapeutic candidate development can be aided by AI in designing safer, more effective drugs, such as for cancer, paving the way for drug discovery in the future. This compound is likely to be developed as a therapeutic agent for treating CRC after extensive experimental validation due to its favorable electronic properties and potential binding with target proteins. These results align with previous studies that emphasize the importance of natural compounds in cancer treatment and highlight the potential of AI-driven drug discovery in developing safer and more effective therapies for colorectal cancer.

Conclusion

Recent studies have implicated ribosomal protein RPS20 in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer, with its mutation V50S contributing to the progression of malignant cells. In this study, artificial intelligence techniques were applied to optimize natural compounds, leading to the identification of an AI-enhanced Indirubin derivative. Among the 20 screened compounds, this optimized lead from indirubin exhibited superior binding affinity (− 6.7 kcal/mol), favorable dynamic stability in molecular dynamics simulations, and improved pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiles compared to the parent compound. Notably, the AI-enhanced lead demonstrated reduced toxicity, enhanced water solubility, and lower systemic toxicity (Toxicity Class 5 vs. Class 4 for Indirubin). These findings support its potential as a safer and more effective candidate for future colorectal cancer therapy. Further in-vitro and in-vivo models will be required to confirm its predicted pharmacological efficacy and safety of the AI-enhanced lead.

Limitations and future prospectives

While the study shows promise, it has some limitations. The analysis was conducted on a small set of 20 natural compounds, and the results are based on in silico methods, which require experimental validation. The focus on RPS20 protein mutations limits applicability to all colorectal cancer cases, and the predicted ADMET properties of AI Lead need to be confirmed in biological systems.

For future research, the AI-enhanced lead compound should undergo experimental validation through in-vitro and in-vivo models to confirm its predicted pharmacological efficacy and safety. Additionally, exploring other genetic mutations linked to colorectal cancer and investigating combination therapies with existing treatments could enhance the potential of indirubin AI Drug lead as an anticancer agent. If successful, clinical trials should follow to assess its safety and efficacy in humans.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The datasets supporting the conclusions of this study including ligand structures (SDF and PDB files), receptor structures, molecular docking results, and molecular dynamics simulation outputs are available in a publicly accessible Zenodo repository: https://zenodo.org/records/15270358?token=eyJhbGciOiJIUzUxMiJ9.eyJpZCI6ImI0MzlmYTRiLTg2ODEtNDcwYy04YTA0LTA4NTJmY2QxOTFlMCIsImRhdGEiOnt9LCJyYW5kb20iOiI4NjY5MmE2ODBlZmMzOGZlMWY1MDc2NDFkOWYyODBhMCJ9.wGRV0mWkpHckbQHTtHoIatNd0pjXgbB3t4NXRlDpdMSJgvqkT2rbi3GugyT77U2R1Wl6bi6soreWXQ-NJ6Tikw.. Additionally, the 3D structure of the target protein, Small ribosomal subunit protein uS10, was obtained from the AlphaFold database (https://alphafold.com/) using the AlphaFold ID: P60866.

References

Brown, J. S. et al. Updating the definition of cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 21(11), 1142–1147 (2023).

Biller, L. H. & Schrag, D. Diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: a review. Jama 325(7), 669–685 (2021).

Siegel, R. et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. Cancer J. Clin., 64(1). (2014).

Rawla, P., Sunkara, T. & Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of colorectal cancer: Incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Gastroenterol. Review/Przegląd Gastroenterologiczny 14(2), 89–103 (2019).

Siegel, R. L. et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. Cancer J. Clin. 73(3), 233–254 (2023).

Freeman, H. J. Colorectal cancer risk in crohn’s disease. World J. Gastroenterology: WJG. 14(12), 1810 (2008).

Board, P. C. G. E. Genetics of Colorectal Cancer (PDQ®): Health Professional Version (PDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet], 2002).

O’Connell, J. B., Maggard, M. A. & Ko, C. Y. Colon cancer survival rates with the New American joint committee on cancer sixth edition staging. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 96(19), 1420–1425 (2004).

Campos, F. et al. Diet and colorectal cancer: Current evidence for etiology and prevention. Nutr. Hosp. 20(1), 18–25 (2005).

Doyle, V. C. Nutrition and colorectal cancer risk: A literature review. Gastroenterol. Nurs. 30(3), 178–182 (2007).

Harriss, D. et al. Lifestyle factors and colorectal cancer risk (2): A systematic review and meta-analysis of associations with leisure‐time physical activity. Colorectal Dis. 11(7), 689–701 (2009).

Dubé, C. et al. The use of aspirin for primary prevention of colorectal cancer: A systematic review prepared for the US preventive services task force. Ann. Intern. Med. 146(5), 365–375 (2007).

Rostom, A. et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors for primary prevention of colorectal cancer: A systematic review prepared for the US preventive services task force. Ann. Intern. Med. 146(5), 376–389 (2007).

Nagtegaal, I. D. & Quirke, P. What is the role for the circumferential margin in the modern treatment of rectal cancer? J. Clin. Oncol. 26(2), 303–312 (2008).

Majumdar, S. R., Fletcher, R. H. & Evans, A. T. How does colorectal cancer present? Symptoms, duration, and clues to location. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 94(10), 3039–3045 (1999).

Normanno, N. et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling in cancer. Gene 366(1), 2–16 (2006).

Tian, Y. et al. Changes in the transcriptome caused by mutations in the ribosomal protein uS10 associated with a predisposition to colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(11), 6174 (2022).

Nieminen, T. T. et al. Germline mutation of RPS20, encoding a ribosomal protein, causes predisposition to hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma without DNA mismatch repair deficiency. Gastroenterology 147(3), 595–598 (2014). e5.

Goudarzi, K. M. & LINDSTRöM, M. S. Role of ribosomal protein mutations in tumor development. Int. J. Oncol. 48(4), 1313–1324 (2016).

De Jong, K. P. et al. Clinical relevance of transforming growth factor α, epidermal growth factor receptor, p53, and Ki67 in colorectal liver metastases and corresponding primary tumors. Hepatology 28(4), 971–979 (1998).

Barozzi, C. et al. Relevance of biologic markers in colorectal carcinoma: A comparative study of a broad panel. Cancer 94(3), 647–657 (2002).

Lee, C. S., Ryan, E. J. & Doherty, G. A. Gastro-intestinal toxicity of chemotherapeutics in colorectal cancer: The role of inflammation. World J. Gastroenterol.: WJG 20(14), 3751 (2014).

Kozovska, Z., Gabrisova, V. & Kucerova, L. Colon cancer: cancer stem cells markers, drug resistance and treatment. Biomed. Pharmacother. 68(8), 911–916 (2014).

Segal, N. H. & Saltz, L. B. Evolving treatment of advanced colon cancer. Annu. Rev. Med. 60, 207–219 (2009).

Duch, W., Swaminathan, K. & Meller, J. Artificial intelligence approaches for rational drug design and discovery. Curr. Pharm. Des. 13(14), 1497–1508 (2007).

Gertrudes, J. C. et al. Machine learning techniques and drug design. Curr. Med. Chem. 19(25), 4289–4297 (2012).

Lima, A. N. et al. Use of machine learning approaches for novel drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 11(3), 225–239 (2016).

Klambauer, G., Hochreiter, S. & Rarey, M. Machine learning in drug discovery ACS Publ. 945–946 (2019).

Schneider, P. et al. Rethinking drug design in the artificial intelligence era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 19(5), 353–364 (2020).

Li, Y. H. et al. Role of phytochemicals in colorectal cancer prevention. World J. Gastroenterology: WJG. 21(31), 9262 (2015).

Dali, Y. et al. Computational drug design and exploration of potent phytochemicals against cancer through in silico approaches. Biomedical Lett. 5(1), 21–26 (2019).

Kar, S. & Roy, K. QSAR of phytochemicals for the design of better drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 7(10), 877–902 (2012).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with alphafold. Nature 596(7873), 583–589 (2021).

Schmiedel, J. M. & Lehner, B. Determining protein structures using deep mutagenesis. Nat. Genet. 51(7), 1177–1186 (2019).

Hollingsworth, S. A. & Karplus, P. A. A fresh look at the Ramachandran plot and the occurrence of standard structures in proteins. (2010).

Colovos, C. & Yeates, T. O. Verification of protein structures: patterns of nonbonded atomic interactions. Protein Sci. 2(9), 1511–1519 (1993).

Jiménez, J. et al. DeepSite: protein-binding site predictor using 3D-convolutional neural networks. Bioinformatics 33 (19), 3036–3042 (2017).

Kim, S. et al. PubChem 2019 update: improved access to chemical data. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(D1), D1102–D1109 (2019).

Naveed, M. et al. The natural breakthrough: Phytochemicals as potent therapeutic agents against spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 1529 (2024).

Huey, R., Morris, G. M. & Forli, S. Using AutoDock 4 and AutoDock Vina with AutoDockTools: A tutorial. Scripps Res. Inst. Mol. Graph. Lab. 10550(92037), 1000 (2012).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 42717 (2017).

Bai, Q. et al. WADDAICA: A webserver for aiding protein drug design by artificial intelligence and classical algorithm. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 19, 3573–3579 (2021).

Sadia, H. et al. Natural AI-based drug designing by modification of ascorbic acid and Curcumin to combat buprofezin toxicity by using molecular dynamics study. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 28445 (2024).

Vilar, S., Cozza, G. & Moro, S. Medicinal chemistry and the molecular operating environment (MOE): application of QSAR and molecular Docking to drug discovery. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 8(18), 1555–1572 (2008).

Laskowski, R. A. & Swindells, M. B. LigPlot+: Multiple ligand–protein Interaction Diagrams for Drug Discovery (ACS, 2011).

Yuan, S., Chan, H. S. & Hu, Z. Using PyMOL as a platform for computational drug design. Wiley Interdiscip.Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 7(2), e1298 (2017).

Jejurikar, B. L. & Rohane, S. H. Drug designing in discovery studio (2021).

Ferreira, L. G. et al. Molecular docking and structure-based drug design strategies. Molecules 20(7), 13384–13421 (2015).

Hildebrand, P. W., Rose, A. S. & Tiemann, J. K. Bringing molecular dynamics simulation data into view. Trends Biochem. Sci. 44(11), 902–913 (2019).

Rasheed, M. A. et al. Identification of lead compounds against Scm (fms10) in Enterococcus faecium using computer aided drug designing. Life 11(2), 77 (2021).

Shivakumar, D. et al. Prediction of absolute solvation free energies using molecular dynamics free energy perturbation and the OPLS force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 6(5), 1509–1519 (2010).

Zaheer, M. et al. Uncovering the impact of SARS-CoV2 Spike protein variants on human receptors: A molecular dynamics docking and simulation approach. J. Infect. Public Health. 16 (10), 1544–1555 (2023).

Banerjee, P. et al. ProTox 3.0: A webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. gkae303 (2024).

Trayes, K. P. & Cokenakes, S. E. Breast cancer treatment. Am. Family Phys. 104(2), 171–178 (2021).

Mármol, I. et al. Colorectal carcinoma: A general overview and future perspectives in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18(1), 197 (2017).

Amiot, J. et al. New RPS20 gene variant in colorectal cancer diagnosis: Insight from a large series of patients. Fam. Cancer. 24(1), 22 (2025).

Janakiram, N. B. & Rao, C. V. The role of inflammation in colon cancer Inflamm. Cancer 25–52 (2014).

Ungprasert, P. et al. Individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 26(4), 285–291 (2015).

Hessler, G. & Baringhaus, K. H. Artificial intelligence in drug design. Molecules 23(10), 2520 (2018).

Shen, C. et al. Biochemical and clinical effects of RPS20 expression in renal clear cell carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 49(1), 22 (2022).

Singh, V. et al. RNA binding proteins as potential therapeutic targets in colorectal cancer. Cancers 16(20), 3502 (2024).

Naveed, M. et al. Artificial intelligence assisted pharmacophore design for Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia with gamma-tocotrienol: A toxicity comparison approach with asciminib. Biomedicines 11 (4), 1041 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Indirubin induces apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells via the mitochondrial pathway. Am. J. Transl. Res. 16(10), 6119 (2024).

Barbosu, S. Harnessing AI To Accelerate Innovation in the Biopharmaceutical Industry (Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, 2024).

Ali, N. et al. Deep learning and artificial intelligence for drug discovery, application, challenge, and future perspectives. Discov. Appl. Sci. 7 (6), 1–16 (2025).

Naveed, M. et al. Assessment of Melia azedarach plant extracts activity against hypothetical protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis via GC-MS analysis and in-silico approaches. J. Comput. Biophys. Chem. 23(3), 299–320 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge that no individuals or organizations were involved in the development, funding, or support of this work. This research was solely conducted by the authors, and no external contributions, financial or otherwise, were received or utilized in the execution of this study.

Funding

This review was conducted without external funding. The authors would like to clarify that no financial support or grants from any organization, institution, or individual were received for the completion of this review. The research was carried out as part of the author’s academic and professional responsibilities, and they did not rely on any external sources of funding for the design, execution, or publication of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization N.A., R.A.; Methodology A.S. and N.A..; Software, N.A., R.A., A.S. and A.A.; Validation, A.A., and A.A..; Formal analysis, R.A..; Investigation, N.A..; Data curation A.S..; writing original draft preparation, A.S., A.A. and N.A..; writing review and editing, N.A., A.S. and A.A..; visualization, N.A., A.A..; supervision, Nouman and A.S..; project administration; Nouman and Adeeba Ali.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ali, N., Akbar, R., Saleem, A. et al. AI based natural inhibitor targeting RPS20 for colorectal cancer treatment using integrated computational approaches. Sci Rep 15, 24906 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07574-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07574-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

AI-assisted identification of innovative phytochemicals from Aizoon canariense aimed at brachyury protein in chordoma: a computational strategy

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Discovery of natural PDE-5 inhibitors in NO signalling pathways for the human erectile dysfunction management: a multi-layered in silico assessment

In Silico Pharmacology (2025)