Abstract

The emergence of multidrug-resistant pathogens underscores the urgent need for novel antimicrobial agents. In this study, ten endophytic fungal isolates (Ls1–Ls10) were isolated for the first time from Lavandula stricta and evaluated for their antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella oxytoca, and Candida albicans. The most potent fungal isolate Ls1 was identified as Sarocladium kiliense using morphological and molecular techniques. Phytochemical analysis indicated that the S. kiliense extract is abundant in bioactive compounds, including phenolics, tannins, flavonoids, and alkaloids. The GC mass analysis proved the presence of 41 active compounds in the S. kiliense. Extract including; Benzene, (1-propylnonyl) (9.87%), Hexadecanoic acid (8.05%), Prostaglandin A1-biotin (6.77%), Docosene (6.69%), Octadecenoic acid (5.55%), and 1-Nonadecene (5.16%). The crude extract of S. kiliense showed outstanding anticancer activity against cancerous Hep-G2 and MCF-7 cell lines with IC50 of 31.7 and 49.8 µg/ml, respectively. This isolate exhibited significant antimicrobial activity, with inhibition zones ranging from 16.1 ± 0.1 mm to 35.5 mm. MICs varied between 62.5 and 250 µg/mL. S. kiliense exhibited antioxidant activity and antibiofilm activities. The S. kiliense extract demonstrated concentration-dependent antibiofilm activity. In conclusion, S. kiliense as a hopeful home of bioactive combinations with potent antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer, and antibiofilm activities, offering the potential for combating multidrug-resistant pathogens and therapeutic applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid extent of multidrug-resistant microorganisms (MDROs) presents a serious global public health challenge, diminishing the effectiveness of conventional antibiotics and contributing to rising morbidity and mortality rates. Consequently, infections that were once easily treatable are becoming increasingly difficult to manage, leading to prolonged illness, higher healthcare costs, and increased mortality1. This alarming trend underscores the urgent need for novel effective antimicrobial agents derived from alternative sources2. Biofilm formation by pathogenic microorganisms further complicates treatment strategies, as biofilms confer resistance to antimicrobial agents and host immune responses3. The structure of biofilms is a complex, multi-step process involving initial attachment, micro colony formation, maturation, and eventual dispersion of cells to colonize new niches4. This mode of growth offers microorganisms several advantages, such as enhanced resistance to antimicrobial agents. The development of agents capable of inhibiting biofilm formation or disrupting established biofilms is a critical area of research5.

Endophytes, residing asymptomatically within plant tissues, engage in symbiotic relationships and synthesize compounds that can confer protection to their host plants against pathogens. These metabolites exhibit antimicrobial, antioxidant, and antibiofilm potency, positioning endophytic fungi as promising candidates in the search for new therapeutic agents. Endophytic fungi exhibit multiple mechanisms to combat MDROs. One primary approach involves the production of diverse secondary metabolites with potent antimicrobial properties, such as alkaloids, terpenoids, and polyketides, which can inhibit or kill resistant pathogens6. Moreover, endophytic fungi may outcompete pathogens within the host environment, effectively suppressing pathogen growth7. They can also produce enzymes that degrade pathogenic structures or disrupting biofilm formation and virulence factor expression in MDROs. Fungal endophytes play a significant role in combating cancer by producing bioactive metabolites that induce apoptosis, inhibit tumor cell proliferation, and suppress angiogenesis8. These compounds often target cancer cells selectively, minimizing damage to healthy tissues9. Endophytes also enhance the production of antioxidants, reducing oxidative stress linked to cancer development10. Their ability to modulate immune responses further contributes to their anticancer potential. Research continues to explore these natural sources for novel and effective cancer therapies11.

Lavandula stricta, a species within the lavender genus (Lavandula), is native to arid and semi-arid regions of North Africa, including Egypt12. Although specific traditional medicinal uses of L. stricta are not extensively recorded, related species within the Lavandula genus have a rich history in herbal medicine. L. stricta was considered as a promising source of natural antioxidants and bioactive compounds. The essential oil of L. stricta was rich in α-pinene, linalool, and other bioactive monoterpenes, while the methanolic extracts showed considerable phenolic content13. Isolating and studying endophytes from L. stricta could lead to the explore of novel compounds due to the unique environmental adaptations and photochemistry of L. stricta, its fungal endophytes may harbor distinct bioactive metabolites worthy of exploration14.

The objective of our study was to isolate and identify endophytic fungi from L. stricta, with a specific focus on characterizing the antimicrobial, antibiofilm, antioxidant and anticancer properties of the most potent isolate. By evaluating its bioactive compounds and assessing its efficacy against multidrug-resistant pathogens, this research aims to explore the potential of endophytic fungi as a novel and alternative source of therapeutic agents.

Materials and methods

Isolation and characterization of endophytic fungi

Lavandula stricta (Ls) plants were collected from Ain Sokhna, the Red Sea, the Suez Governorate in Egypt (29.530865, 32.375677). Experimental research and field studies on plants, including the collection of plants and identification, comply with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation by Prof. Dr. Abdou Marie Hamed at the Botany and Microbiology Department, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt. The plant was kept in the Faculty of Science herbarium, Al-Azhar University (Voucher no. 725).

Healthy plant parts rinsed twice with sterilized distilled water (SDH2O) and then disinfected using 70% CH3CH2OH for 60 S, followed by treatment with 4% NaOCl for another 60 S, finally rinsed with SDH2O. The Ls sections were placed in sterile Petri dishes (9 cm in diameter) containing sterilized PDA medium. For control, sterile Petri dishes (9 cm in diameter) containing sterilized PDA medium inoculated with the solution of sterilized sections to ensure that fungi are endophytes. The plates were incubated in the dark at 28 °C for 21 days and monitored daily15. Emerging mycelium was carefully collected and subcultured. The isolated fungi were then assessed for their antimicrobial activity against pathogenic microorganisms, and the most effective strain was identified based on colony variations, morphological characteristics, and genetic analysis. Finally, the purified fungal isolates were stored at 4 °C for further studies. The molecular identification of the endophytic fungus was conducted by amplifying the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region. Genomic DNA was extracted and purified using the Quick-DNA Fungal Microprep Kit (Zymo Research, D6007). PCR amplification was performed using ITS-specific primers: ITS1-F (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS2-R (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′). The amplified products were then purified using the Gene JET PCR Purification Kit (Thermo Scientific, K0701). The purified sequences were analyzed through the BLAST tool from NCBI to determine the closest genetic matches. Verified sequences were subsequently submitted to the Gen Bank database, each assigned a unique accession number for global accessibility. To evaluate evolutionary relationships, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with MEGA software version 5.016.

Extraction of active metabolites

The secondary metabolites of S. kiliense were extracted by culturing the fungus in 500 mL of PD broth within a 1 L flask, followed by incubation at 28 °C for 15 days. Following incubation, the culture was filtered, and the resulting supernatant was combined with CH3COOC2H5 in a 1:1 V/V and stored at 4 °C overnight. The metabolites were subsequently separated, and the extract was evaporated at 40 °C to yield the ethyl acetate crude extract (EACE) and stored at 4 °C for subsequent experimental use17.

Antimicrobial activity

Muller Hinton agar (MHA, India) was employed to assess the antibacterial activity of S. kiliense against bacteria, while PDA was employed to evaluate its antifungal activity against C. albicans. The surface of the prepared MHA and PDA was cultured with 24-hour-old cultures of clinical isolates of S. aureus, K. oxytoca, B. subtilis, and E. coli, C. albicans ATCC10231. All clinical isolates of S. aureus, K. oxytoca, B. subtilis, and E. coli were obtained from bacteriology laboratory at Microbiology Department, faculty of science, Al Azhar University, Cairo. Egypt and were identified using standard microbiological methods in previous study18. 100 µl of each compound was transferred to each well (6 mm) individually and left at 4 ℃ for 2 h. Amikacin 30 µg was used as a control for bacteria and fluconazole 25 µg for CA. Plates were incubated for 24 h, 48 h at 37 °C, and 28 °C for bacteria and CA. After incubation, inhibitory zones were measured and reported19.

Determination of MIC

The MIC of S. kiliense EACE against S. aureus, K. oxytoca, B. subtilis, and E. coli, C. albicans ATCC10231 were determined using a broth microdilution assay. Serial dilutions of S. kiliense EACE (100 µl) were supplementary to microtiter plate wells inoculated with 100 µl of double-strength MHB, achieving final concentrations of 1000: 31.25 µg/ml. 50 µl bacterial suspension was inoculated to all wells except the -Ve control (SDH2O + MHB) and + Ve control (The first row used as + Ve control (using MHB + microorganisms) while second row used as -Ve control (using SDH2O + MHB only without any microorganisms). + Ve control ensured broth adequacy, incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, then addition of 30 µl resazurin (0.02% wt./v) and re-incubation. Color modification from blue to purple indicated bacterial growth. Sterile controls remained unchanged, confirming no contamination. Experiments were performed in duplicate, and mean values were calculated20.

Anti-biofilm ability

The anti-biofilm activity was assessed using 96-well microtiter plates21. Each well of a sterile microtiter plate was filled with 100 µL of MHB for bacteria Sabouraud Dextrose Broth for Candida and inoculated with 10 µL of an overnight bacterial and Candida culture suspension (OD620 0.05 ± 0.02). The EACE was then added at concentrations of ½, ¼, and 1/8 × MIC, and incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. Then, biofilms were fixed using absolute alcohol, stained with 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet, and incubated for 30 min. After drying, 200 µL of 33% acetic acid was added, and the OD of the stained biofilms was measured at 630 nm. The control used in this experiment involved the growth of microorganisms without any treatment, and the optical density was read. The results were then used in the following equation to calculate the percentage of biofilm inhibition.

.

Cytotoxicity and anticancer activity of S. kiliense EACE

The cytotoxicity experiment was performed according to the MTT procedure established by Van de Loosdrecht, et al.22. The MCF-7 and Wi-38, sourced from ATCC, were utilized to evaluate the cytotoxic or anticancer effects of S. kiliense EACE, respectively. The measured OD of the cells at 560 nm was utilized to calculate cell viability and inhibition % 23, following Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively:

.

Anti-oxidant activity

The evaluation of the anti-oxidant activity of S. kiliense was conducted through the DPPH radical scavenging assay, which was adapted to assess the extract’s ability to scavenge free radicals21. In the experiment, 100 µL of the DPPH solution was mixed with 100 µL of the sample in a 96-well microplate and allowed to incubate at 25O C for 0.5 h. Ascorbic acid used as + Ve control for comparison. Absorbance was recorded at 490 nm with 100% methanol serving as the control. The DPPH scavenging activity was assessed using the subsequent formula:

To evaluate the anti-oxidant potential, different concentrations of S. kiliense EACE (1000: 7.81 µg/mL) were tested. The results were expressed as DPPH scavenging activity (%), and the IC50 value was determined, providing insight into the extract’s antioxidant strength. In addition, the ABTS assay used to assess the anti-oxidant activity of S. kiliense. This method was conducted following the protocol described by Lee et al.,23offering an alternative approach to evaluate the S. kiliense EACE ability to neutralize free radicals.

Phytochemical analysis of S. kiliense

The phytochemical analysis of S. kiliense was conducted following the methodology.

Determination of S. kiliense total flavonoid content (SKTFC)

SKTFC was determined using the AlCl₃ method. One mL of S. kiliense extract was dissolved in 2 mL methanol. Separate 5% solutions of NaNO₃, NaOH, and AlCl₃ were prepared. For analysis, 200 µL of the extract was mixed with 75 µL of 5% NaNO₃, incubated for 5 min, followed by the addition of 1.25 mL AlCl₃ and 0.5 mL NaOH. The mixture was sonicated, incubated for another 5 min, and absorbance was measured at 510 nm24.

Determination of S. kiliense total phenolic content (SKTPC)

SKTPC of the S. kiliense extracts was evaluated using a colorimetric assay with Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. One mL of the extract was dissolved in 2 mL of CH3OH, and then 500 µL was mixed with 2.5 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and 2.5 mL of a 75 g/L Na₂CO₃. Absorbance was measured at 765 nm after incubated at 25 °C for 2 h25.

Determination of S. kiliense total tannin content (SKTTC)

SKTTC was assayed by the vanillin-HCl (VHCl) method, with tannic acid as the standard. A 400 µL aliquot of S. kiliense extract was combined with 3 mL vanillin 4% and 1.5 mL of HCl concentrated .Then absorbance measured at 500 nm after incubated at 25 °C for 15 min25.

Total alkaloid content (TAC) determination

One mL of S. kiliense extract was washed three times with chloroform. The pH was adjusted to 7 using 0.1 N NaOH, after which 5 mL of Bromocresol Green solution and 5 mL of phosphate buffer (pH 4.7) were added and shaken vigorously to form a complex, which was then extracted using chloroform. TAC was quantified by measuring absorbance at 470 nm25.

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

Metabolites in S. kiliense EACE were analyzed using GC-MS (Trace GC1310-ISQ, Thermo Scientific) with a TG-5MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). The oven temperature started at 50 °C, increasing at 5 °C/min to 230 °C (held for 2 min) and then to 290 °C (held for 2 min). The injector and MS transfer line were set at 250 °C and 260 °C. A 1 µL sample was injected at 250 °C using helium as the carrier gas (split ratio 1:30). The MS operated in EI mode (70 eV, 200 °C) with a 40–1000 m/z scan range. Identification used WILEY 09 and NIST 11 libraries21.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Minitab 18.3 with three replicates. Descriptive analysis, including mean and standard error, was conducted.

Results and discussion

Isolation and characterization of endophytic fungi

In the current study, ten fungal isolates were isolated and purified fungal isolates (Ls1 to Ls10), then screened against S. aureus, K. oxytoca, B. subtilis, and E. coli, C. albicans ATCC10231. The highest effective fungal isolate was Ls1, thus identified as Sarocladium sp. Sarocladium sp colonies on PDA appear white to cream-colored initially, turning pale yellow with age (Fig. 1A). The texture was cottony, with a dense mycelial growth pattern. The reverse side of the colony is pale yellow to dark (Fig. 1B). Mycelium was septate and hyaline; conidiophores are slender. Conidia were unicellular, ellipsoidal to cylindrical, and typically formed in. Conidia appear smooth-walled and may form in chains or clusters (Fig. 1C). To validate the morphological identification, molecular analysis was conducted for the fungal isolate Ls1. Results revealed that fungal isolate Ls1 was similar to Sarocladium kiliense with 99% according to BLAST on gene bank. Then, the sequence of S. kiliense was deposited in gene bank with accession number PV248633.1. and phylogenetic tree was created in Fig. 1D.

By isolating these fungi from L. stricta, researchers can better understand their ecological roles, interactions with the host plant, and potential use in medicine, agriculture, and biotechnology. The first isolation of endophytic fungi from L. stricta marks a significant step in exploring the plant’s hidden microbial diversity and its potential applications. S. kiliense was reported as an endophytic fungus isolated from a healthy Aloe dhufarensis Lavranos desert-adapted plant, highlighting its potential role in plant health and secondary metabolite production. As an endophyte, S. kiliense resides within the plant tissues without causing disease, possibly contributing to host defense mechanisms, growth enhancement26. The isolation and identification of the fungal strain Ls1 as S. kiliense underscore its potential as a prolific source of antimicrobial agents. The morphological characteristics observed white to cream-colored colonies transitioning to pale yellow, cottony texture with dense mycelial growth, and septate, hyaline mycelium were consistent with descriptions in existing literature27. The isolation and study of endophytic fungi from stress-resilient plants present a promising avenue for the discovery of novel bioactive compounds with significant medical applications due to the endophytic fungi are shaped by a wide range of factors such as environmental conditions, the type of host tissue, plant evolutionary lineage, geographic region, seasonal variations, and agricultural practices (organic vs. conventional). Additionally, surrounding vegetation and soil characteristics play a significant role28.

Antimicrobial activity

The Table 1 presents data on the antimicrobial activity of S. kiliense EACE against various microbial strains, highlighting its effectiveness. S. kiliense EACE exhibits highly activity against both G + ve, G-ve, and C. albicans, with varying inhibition zone diameters, as shown in Table 1; Fig. 2. Notably, the inhibition zones for K. oxytoca, S. aureus, B. subtilis, E. coli, and C. albicans were 35.5 mm, 32.3 mm, 30.1 mm, 21 mm, and 16.1 ± 0.1 mm, respectively. The antibacterial activity of S. kiliense can be supported the previous study that demonstrated that antibacterial activity of L. stricta essential oil was evaluated against a range of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria including Salmonella typhi, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Listeria innocua, S. aureus, and E. coli29.

Determination of MIC

Table 2 presents the MIC of S. kiliense EACE against tested microorganisms. The MIC values ranging from 62.5 to 250 µg/mL, as illustrated in Table 2; Fig. 3. The S. kiliense EACE exhibited notable activity, with MICs of 62.5 µg/ml against B. subtilis and K. oxytoca, 125 µg/ml against C. albicans (ATCC10231), and 250 µg/ml against both S. aureus and E. coli. This broad-spectrum activity may be due to S. kiliense EACE-derived bioactive compounds. This is also consistent with many previous studies that have proven the presence of biologically active substances in extracts of endophytic fungi30. The MICs further elucidate the potency of S. kiliense EACE. MIC values ranging from 62.5 µg/mL to 250 µg/mL against pathogens like B. subtilis, K. oxytoca, and C. albicans demonstrate the extract’s efficacy at relatively low concentrations. The mechanism of antimicrobial activity of S. kiliense EACE may be due to the disruption of antibiofilm properties. The anti-biofilm activity of S. kiliense extract adds another dimension to its antimicrobial profile. The antimicrobial activity could be confirmed by the presence of antimicrobial compounds as Heptacosane, Cyclohexanecarboxy lic acid,2-phenylethyl ester, Dodecanoic acid, Hexadecane, 1-Nonadecene, Octadecane11,28.

Anti-biofilm ability

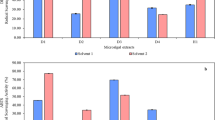

The in vitro evaluation of the anti-biofilm activity of S. kiliense EACE against the tested pathogens (Fig. 4) revealed a concentration-dependent reduction in biofilm formation across all species. C. albicans exhibited the highest inhibition, with biofilm reduction ranging from 67.55 ± 1.13% at ½ MIC to 40.29 ± 0.89% at 1/8 MIC. In contrast, E. coli showed the lowest reduction, with inhibition percentages varying from 28.99% at ½ MIC to 7.99% at 1/8 MIC. The antibiofilm activity was confirmed by antibiofilm components in S. kiliense EACE such as Prostaglandin A1-biotin, Octacosanol, Penta tri acontene, Behenic alcohol, and Eicosane. Lavandula essential oil demonstrated potent biofilm degradation activity, effectively reducing bacterial adhesion. The ability of Lavandula EACE to significantly impair Campylobacter jejuni motility further underscores their impact on biofilm inhibition by downregulating key genes involved in adhesion and biofilm formation31.

Cytotoxicity and anti-cancer activity

In our study, the EACE of S. kiliense was emulated for cytotoxicity toward Wi 38 normal cell line at different concentrations as illustrated in Fig. 5. Results revealed that, IC50 of S. kiliense EACE was 226.5 µg/ml. This indicates that at this concentration, S. kiliense EACE reduces cell viability by 50%, highlighting its potency in inducing cytotoxicity. Therefore, the S. kiliense EACE is considered safe to use. Therefore, the safe and maximum non-toxic concentrations of the EACE were determined and evaluated for their anticancer potential. Evaluating the cytotoxicity of compounds toward normal cell lines involves assessing their effects on cell viability, proliferation, and morphology. This evaluation is crucial for determining the safety profile of potential therapeutic agents before clinical application16. Materials with an IC50 value of > 90 µg/mL are often categorized as non-cytotoxic32. The safe and optimal non-toxic concentrations of the extract were assessed for anticancer efficacy.

The highest non-toxic concentrations of S. kiliense EACE were evaluated for their anticancer effects on Hep-G2 and MCF-7 cancer cell lines (Fig. 6). The results showed that the IC50 values of S. kiliense EACE were 31.7 µg/ml for Hep-G2 and 49.8 µg/ml for MCF-7. In comparison, Taxol, a standard anticancer agent, exhibited IC50 values of 10.8 µg/ml for Hep-G2 and 7.9 µg/ml for MCF-7. Our results demonstrate the anticancer potential of S. kiliense EACE, an endophytic fungal extract, against Hep-G2 (liver cancer) and MCF-7 (breast cancer) cell lines, with IC50 values of 31.7 µg/ml and 49.8 µg/ml, respectively. These findings indicate that S. kiliense EACE is more effective against Hep-G2 cells compared to MCF-7 cells, suggesting a possible selectivity in its mechanism of action toward liver cancer. In comparison, Taxol, a well-established anticancer drug showed significantly lower IC50 values of 10.8 µg/ml for Hep-G2 and 7.9 µg/ml for MCF-7, reflecting its potent and broad-spectrum anticancer activity. These results illustrated the selective toxicity of S. kiliense EACE against cancer cells; thus, it may be used as an anticancer agents33. Our findings align with a recent study highlighting the anticancer potential of Lavandula, which showed notable cytotoxic activity against MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines and achieved a 43.29% reduction in tumor size in vivo, with complete tumor regression observed in 12.5% of treated mice34.

Antioxidant activity

In our investigation, we assessed the antioxidant potential of S. kiliense EACE across a concentration range of 1000 to 7.81 µg/mL utilizing both DPPH and ABTS assays, as depicted in Fig. 7. The findings indicated that the EACE exhibited an IC50 value of 202.08 µg/mL in the DPPH assay, in contrast to the IC50 of 8.9 µg/mL for ascorbic acid. Similarly, in the ABTS assay, the EACE demonstrated an IC50 of 169.79 µg/mL, whereas ascorbic acid presented an IC50 of 7.61 µg/mL. The antioxidant activity of S. kiliense EACE can be explained by the phytochemical analysis that revealing high levels of phenolics, alkaloids, flavonoids, and tannins. The antioxidant activity of S. kiliense EACE also proved by the presence of antioxidant compounds that achieved by GC mass analysis as the following; Prostaglandin A1-biotin, Linoleic acid ethyl ester35. Our results can be explained by the study reported that Lavandula showed the modrate DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging and metal ion-reducing activities, likely due to its high content of oxygenated sesquiterpenes, particularly α-bisabolol and due to synergistic effects of its monoterpene-rich composition36.

Phytochemical analysis of S. kiliense EACE

Total phenolics, alkaloids, flavonoids, and tannins was quantified for S. kiliense EACE as shown in (Fig. 8). Results revealed that presence high levels of phenolics, alkaloids, flavonoids, and tannins in the S. kiliense EACE. A high phenolic content (809.83 µg/mL) in the S. kiliense EACE may exhibit strong antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory activities. Also playing a crucial role in protecting cells from oxidative damage and free radicals. Tannins are polyphenolic compounds known for their astringent biological properties. The presence of tannins (250.2 µg/mL) indicates that the EACE may contribute to antimicrobial, antifungal, and anti-inflammatory effects. The moderate flavonoid content of 232.23 µg/mL in the S. kiliense EACE suggests a potential role in neutralizing free radicals, inhibiting bacterial growth, and modulating immune responses. Alkaloids are bioactive secondary metabolites known for their antimicrobial, antifungal, and medicinal properties. The high alkaloid content (920.5 µg/mL) in this EACE suggests strong antimicrobial potential and possible pharmacological applications, such as anti-bacterial, anti-fungal, and anti-cancer activities. Phenolic compounds are renowned for their anti-oxidant properties, playing a crucial role in neutralizing free radicals and mitigating oxidative stress37. The presence of these active components supports the symbiotic relationship between S. kiliense and L. stricta and explains the L. stricta ability to adapt to this difficult environment. It also explains the presence of these substances in the plant when it is analyzed, as previous studies have proven the presence of these compounds in the plant extract38.

GC-MS analysis

Our findings, as presented in Table 3; Fig. 9, identified 41 bioactive compounds in the S. kiliense EACE. This EACE contains a diverse mixture of fatty acids, hydrocarbons, and aromatic benzene derivatives, each contributing to distinct biological activities. A significant number of these compounds demonstrate antibacterial and antibiofilm properties, making the EACE highly relevant for pharmaceutical and medical applications. Among the most abundant compounds were Benzene, (1-propylnonyl) (9.87%), Hexadecanoic acid (8.05%), Prostaglandin A1-biotin (6.77%), Docosene (6.69%), Octadecenoic acid (5.55%), and 1-Nonadecene (5.16%). Most of the active compounds present in the EACE belong to the antimicrobial category, which includes Dodecanoic acid, Hexadecane, Oleic Acid, and Eicosane. Several compounds exhibit antibacterial and antibiofilm activity, which is crucial for combating biofilm-related infections that are often resistant to conventional treatments. Notable examples include Linoleic acid ethyl ester, Behenic alcohol, and Octacosanol, which play a vital role in preventing bacterial colonization and persistence. Beyond antimicrobial activity, the EACE contains anticancer and antiviral compounds, particularly benzene derivatives such as (1-pentylheptyl, 1-butyloctyl, and 1-propylnonyl). Additionally, anti-inflammatory compounds like Hexadecanoic acid and Benfluorex contribute to reducing inflammation, making them beneficial for conditions involving immune responses. The presence of 4-Hydroxyvalproic acid, a known anticonvulsant, further expands the therapeutic potential of this EACE. The identified of 41 bioactive compounds within the S. kiliense EACE, including fatty acids such as Hexadecanoic acid and oleic acid have been documented for their antibacterial properties39. The detection of compounds with known antibiofilm activity, such as linoleic acid ethyl ester and octacosanol, is particularly significant. The ability of S. kiliense EACE to disrupt biofilm formation suggests a potential therapeutic avenue for combating persistent infections40. GC-MS analysis results align with previous studies reporting a rich composition of bioactive compounds in L. stricta, mainly monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes, which are linked to its pharmacological potential and may be associated with the endophytic fungus S. kiliense. Key constituents such as 1,8-cineole, camphor, borneol, and linalool have been identified13.

Conclusion

This study highlights S. kiliense as a highly promising endophytic fungus isolated from L. stricta, demonstrating significant potential in addressing the global challenge of multidrug-resistant pathogens. The phytochemical analysis discovered a rich profile of bioactive compounds, including phenolics, tannins, flavonoids, and alkaloids, which contribute to its potent antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer, and antibiofilm activities. The EACE exhibited remarkable antimicrobial efficacy against a range of pathogens, along with concentration-dependent antibiofilm properties, making it a strong candidate for developing novel therapeutic agents. Furthermore, the outstanding anticancer activity of S. kiliense against Hep-G2 and MCF-7 cell lines, coupled with its antioxidant potential, underscores its multifaceted therapeutic applications. The presence of 41 active compounds, as identified by GC-MS analysis, further validates its pharmacological potential. These findings position S. kiliense as a valuable natural resource for combating drug-resistant infections and cancer, paving the way for future research into its clinical applications and developing new bioactive formulations.

Data availability

All data underlying the findings described in our manuscript were inserted in the manuscript.

References

Abdelmotaleb, M. M., Elshikh, H. H., Abdel-Aziz, M. M., Elaasser, M. M. & Yosri, M. Evaluation of antibacterial efficacy and phytochemical analysis of Echinacea purpurea towards MDR strains with clinical origins. Al-Azhar Bull. Sci. 34, 3. https://doi.org/10.58675/2636-3305.1643 (2023).

Elsharkawy, M. M., Eid, A. M., ATTIA, N. M. & Fouda, A. Bacterial coinfections and antibiogram profiles among ICU COVID-19 patients. Al-Azhar Bull. Sci. 34 https://doi.org/10.58675/2636-3305.1656 (2023). 4.

Elshabrawy, M. M., Labena, A. I., Desouky, S. E., Barghoth, M. G. & Azab, M. S. Detoxification of hexavalent chromium using biofilm forming Paenochrobactrum pullorum isolated from tannery wastewater effluents. Al-Azhar Bull. Sci. 34, 2. https://doi.org/10.58675/2636-3305.1642 (2023).

Shehabeldine, A. M. et al. Antimicrobial, antibiofilm, and anticancer activities of syzygium aromaticum essential oil nanoemulsion. Molecules 28, 5812. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28155812 (2023).

Fareid, M. A. et al. Impeding Biofilm-Forming mediated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and virulence genes using a biosynthesized silver Nanoparticles–Antibiotic combination. Biomolecules 15, 266. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15020266 (2025).

Elghaffar, R. Y. A., Amin, B. H., Hashem, A. H. & Sehim, A. E. Promising endophytic Alternaria alternata from leaves of Ziziphus spina-christi: phytochemical analyses, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 194, 3984–4001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-022-03959-9 (2022).

Abd-Elsalam, K. A. & Hashem, A. H. Enhancing Agroecosystem Productivity with Endophytic Fungi: Unveiling Their Role in Fungal Endophytes Volume II: Applications in Agroecosystems and Plant Protection 3–32. Springer, (2025).

Abd-Elsalam, K. A., Almoammar, H., Hashem, A. H. & AbuQamar, S. F. Endophytic Fungi: Exploring Biodiversity and Bioactive Potential. Fungal Endophytes Volume I: Biodiversity and Bioactive Materials, 1–42. Springer, (2025).

Varghese, S. et al. Endophytic fungi: A future prospect for breast cancer therapeutics and drug development. Heliyon 10, e33995 (2024).

Khalil, A. M. A., Hassan, S. E. D., Alsharif, S. M., Eid, A. M., Ewais, E. E. D., Azab, E., Fouda, A. Isolation and characterization of fungal endophytes isolated from medicinal plant Ephedra pachyclada as plant growth-promoting. Biomolecules 11, 140, (2021).

Abdelaziz, A. M., Attia, M. S., Doghish, A. S. & Hashem, A. H. Endophytic Fungi as a Promising Source for Sulfur-Containing Compounds. In: Fungal Endophytes Volume I: Biodivers. Bioact. Mater. 365–383, Springer, (2025).

Rabei, S. & Elgamal, I. A. Floristic study of saint Katherine protectorate, sinai: with one new record to flora of Egypt. Taeckholmia 41, 32–55. https://doi.org/10.21608/taec.2021.190777 (2021).

Alizadeh, A. & Aghaee, Z. Essential oil constituents, phenolic content and antioxidant activity of Lavandula stricta delile growing wild in Southern Iran. Nat. Prod. Res. 30, 2253–2257. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786419.2016.1155578 (2016).

Habán, M., Korczyk-Szabó, J., Čerteková, S. & Ražná, K. Lavandula species, their bioactive phytochemicals, and their biosynthetic regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 8831. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24108831 (2023).

Abdelaziz, A. M. et al. Efficient role of endophytic Aspergillus terreus in biocontrol of Rhizoctonia solani causing damping-off disease of Phaseolus vulgaris and Vicia faba. Microorganisms 11, 1487 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11061487

Khalil, A., Abdelaziz, A., Khaleil, M. & Hashem, A. Fungal endophytes from leaves of Avicennia marina growing in semi-arid environment as a promising source for bioactive compounds. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 72, 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/lam.13414 (2021).

Hashem, A. H., Al-Askar, A. A., Abd Elgawad, H. & Abdelaziz, A. M. Bacterial endophytes from Moringa oleifera leaves as a promising source for bioactive compounds. Separations 10, 395. https://doi.org/10.3390/separations10070395 (2023).

El-Sayed, M. H., Alshammari, F. A. & Sharaf, M. H. Antagonistic potentiality of actinomycete-derived extract with anti-biofilm, antioxidant, and cytotoxic capabilities as a natural combating strategy for multidrug-resistant ESKAPE pathogens. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 33, 61. https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.2211.11026 (2022).

Alghazzaly, A. M., El-Sherbiny, G. M., Moghannemm, S. A. & Sharaf, M. H. Antibacterial, antibiofilm, antioxidants and phytochemical profiling of Syzygium aromaticum extract. Egypt. J. Aquat. Biology Fisheries. https://doi.org/2610.21608/ejabf.2022.260398 (2022).

Sharaf, M. H. et al. New combination approaches to combat methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Sci. Rep. 11, 4240. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-82550-4 (2021).

Sharaf, M. H. Evaluation of the antivirulence activity of Ethyl acetate extract of (Desf) against. Egypt. Pharm. J. 19, 188–196. https://doi.org/10.4103/epj.epj_10_20 (2020).

Van de Loosdrecht, A., Beelen, R., Ossenkoppele, Broekhoven, M. & Langenhuijsen, M. A tetrazolium-based colorimetric MTT assay to quantitate human monocyte mediated cytotoxicity against leukemic cells from cell lines and patients with acute myeloid leukemia. J. Immunol. Methods. 174, 311–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1759(94)90034-5 (1994).

Lee, K. J., Oh, Y. C., Cho, W. K. & Ma, J. Y. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity determination of one hundred kinds of pure chemical compounds using offline and online screening HPLC assay. Evidence-Based Compl.. Altern. Med. 165457. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/165457 (2015).

ME, S., El-Sherbiny, G. M., Sharaf, M. H., Kalaba, M. H. & Shaban, A. S. Phytochemical analysis, antimicrobial, antioxidant, and cytotoxicity activities of Schinus molle (L.) extracts. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery. 15, 3753–3770. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13399-024-05301-1 (2025).

Abdelaziz, A. M. et al. Anabasis setifera leaf extract from arid habitat: A treasure trove of bioactive phytochemicals with potent antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties. Plos One. 19, e0310298. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0310298 (2024).

Al-Rashdi, F. K. H. et al. Endophytic fungi from the medicinal plant Aloe dhufarensis Lavranos exhibit antagonistic potential against phytopathogenic fungi. South. Afr. J. Bot. 147, 1078–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2020.05.022 (2022).

Eskander, D. M., Atalla, S. M., Hamed, A. A. & El-Khrisy, E. D. A. Investigation of secondary metabolites and its bioactivity from sarocladium kiliense SDA20 using shrimp shell wastes. Pharmacognosy J. https://doi.org/10.5530/pj.2020.12.95 (2020).

Abdelaziz, A. M., Hashem, A. H., Abd-Elsalam, K. A. & Attia, M. S. Biodiversity of Fungal Endophytes. In: Fungal Endophytes Volume I: Biodiversity and Bioactive Materials 43–61, (Springer, 2025).

Mehrnia, M. A. & Barzegar, H. Investigation of functional groups, phenolic and flavonoid compounds, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of Lavandula stricta essential oil: an in vitro study. J. Food Sci. Technol. (Iran). 18, 61–76. https://doi.org/10.52547/fsct.18.119.61 (2021).

Hashem, A. H., Abdelaziz, A. M., Attia, M. S. & Abd-Elsalam, K. A. Biocontrol potential of endophytic Fungi against postharvest grape pathogens. In: Fungal Endophytes Volume II: Applications in Agroecosystems and Plant Protection, 509–530, (Springer, 2025).

Attia, M. S., Hashem, A. H. & Abdelaziz, A. M. Biocontrol of blight diseases using endophytic Fungi. In: Fungal Endophytes Volume II: Applications in Agroecosystems and Plant Protection 383–403 (Springer, 2025).

Ramic, D. et al. Antibiofilm potential of Lavandula preparations against Campylobacter jejuni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 87, e01099–e01021. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01099-21 (2021).

Ioset, J. R., Brun, R., Wenzler, T., Kaiser, M. & Yardley, V. Drug screening for kinetoplastids diseases. A Training Manual for Screening in Neglected Diseases (2009).

Bashar, M. A. et al. Anticancer, antimicrobial, insecticidal and molecular Docking of Sarcotrocheliol and cholesterol from the marine soft coral sarcophyton trocheliophorum. Sci. Rep. 14, 28028. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75446-6 (2024).

Aboalhaija, N. H. et al. Chemical evaluation, in vitro and in vivo anticancer activity of Lavandula angustifolia grown in Jordan. Molecules 27, 5910. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27185910 (2022).

Nagat, S., Eissa, S. & Hoda, A. K. Preventive effects of dill oil on potassium bromate-induced oxidative DNA damage on Garlic root tips. (2024).Sultan Qaboos University Journal for Science

Jalalvand, A. R. et al. Chemical characterization and antioxidant, cytotoxic, antibacterial, and antifungal properties of ethanolic extract of Allium saralicum RM Fritsch leaves rich in linolenic acid, Methyl ester. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 192, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.01.017 (2019).

Eltayeb, L. M., Yagi, S., Mohamed, H. M., Zengin, G., Shariati, M. A., Rebezov, M., Lorenzo, J. M. Essential oils composition and biological activity of Chamaecyparis obtusa, Chrysopogon nigritanus and Lavandula coronopifolia grown wild in Sudan. Molecules 28, 1005, (2023).

Attia, M. S., Soliman, E. A., El Dorry, M. A. & Abdelaziz, A. Fungal endophytes as promising antibacterial agents against ralstonia solanacearum, the cause of wilt disease in potato plants. Egypt. J. Bot. 65, 120–131. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejbo.2024.279261.2777 (2025).

Dobros, N., Zawada, K. & Paradowska, K. Phytochemical profile and antioxidant activity of Lavandula angustifolia and Lavandula x intermedia cultivars extracted with different methods. Antioxidants 11, 711. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11040711 (2022).

Ghavam, M., Afzali, A. & Manca, M. L. Chemotype of Damask Rose with oleic acid (9 octadecenoic acid) and its antimicrobial effectiveness. Sci. Rep. 11, 8027. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87604-1 (2021).

Abdelhamid, A. G. & Yousef, A. E. Combating bacterial biofilms: current and emerging antibiofilm strategies for treating persistent infections. Antibiotics 12, 1005. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12061005 (2023).

Marques, C. N., Morozov, A., Planzos, P. & Zelaya, H. M. The fatty acid signaling molecule cis-2-decenoic acid increases metabolic activity and reverts persister cells to an antimicrobial-susceptible state. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 6976–6991. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01576-14 (2014).

Hameed, R. H., Abbas, F. M. & Hameed, I. H. Bioactive chemical analysis of Enterobacter aerogenes and test of its Anti-fungal and Anti-bacterial activity and determination. Indian J. Public. Health Res. Dev. 9, 442–448. https://doi.org/10.5958/0976-5506.2018.00484.9 (2018).

Roza, D., Sinaga, N. B. & Ambarita, C. Isolation of secondary metabolite compounds of coffee Benalu leaves (Loranthus parasiticus (L.) Merr.) and its antibacterial activity test. J. Pendidikan Kimia. 14, 111–119. https://doi.org/10.24114/jpkim.v14i2.33706 (2022).

Reddy, G. S., Srinivasulu, K., Mahendran, B. & Reddy, R. S. Biochemical characterization of anti-microbial activity and purification of glycolipids produced by dodecanoic acid-undecyl ester. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 11, 4066–4073. https://doi.org/10.5958/0974-360X.2018.00748.5 (2018).

Löscher, W. & Nau, H. Pharmacological evaluation of various metabolites and analogues of valproic acid: anticonvulsant and toxic potencies in mice. Neuropharmacology 24, 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/0028-3908(85)90028-0 (1985).

Fahem, N., Djellouli, A. S. & Bahri, S. Cytotoxic activity assessment and GC-MS screening of two codium species extracts. Pharm. Chem. J. 54, 755–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11094-020-02266-z (2020).

Lee, S. H., Athavankar, S., Cohen, T., Kiselyuk, A. & Levine, F. Reversal of lipotoxic effects on the insulin promoter by Alverine and benfluorex: identification as HNF4α activators. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 1730. https://doi.org/10.1021/cb4000986 (2013).

El-Alem, W. A. et al. Antiviral activities and phytochemical studies on Cleome Droserifolia (Forssk.) delile in Nabq protectorate, South sinai, Egypt. Egypt. J. Bot. 64, 369–380. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejbo.2024.292645.2863 (2024).

Elkady, F. M., Badr, B. M., Hashem, A. H., Abdulrahman, M. S., Abdelaziz, A. M.,Al-Askar, A. A., Hashem, H. R. Unveiling the Launaea nudicaulis (L.) Hook medicinal bioactivities: phytochemical analysis, antibacterial, antibiofilm, and anticancer activities. Frontiers in Microbiology 15, 1454623. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2024. 1454623 (2024).

Sivakumar, R., Jebanesan, A., Govindarajan, M. & Rajasekar, P. Larvicidal and repellent activity of tetradecanoic acid against Aedes aegypti (Linn.) and Culex quinquefasciatus (Say), (Diptera: Culicidae). Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 4, 706–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60178-8 (2011).

Khan, I. H. & Javaid, A. Antifungal, antibacterial and antioxidant components of Ethyl acetate extract of Quinoa stem. Plant. Prot. 3, 125–130. https://doi.org/10.33804/pp.003.03.0150 (2019).

Octarya, Z., Novianty, R., Suraya, N. & SARYONO, S. Antimicrobial activity and GC-MS analysis of bioactive constituents of Aspergillus fumigatus 269 isolated from Sungai Pinang hot spring, riau, Indonesia. Biodiversitas J. Biol. Diversity 22 (2021).

Al-Shammari, L. A., Hassan, W. H. & Al-Youssef, H. M. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil and lipid content of Carduus pycnocephalus L. growing in Saudi Arabia. J. Chem. Pharm. Res. 4, 1281–1287 (2012).

Suekaew, N. Chemical constituents and antibacterial activity of rhizomes from Globba schomburgkii Hook. (2019).

Abdel-Hady, H., Abdel-Wareth, M. T. A., El-Wakil, E. A. & Helmy, E. A. Identification and evaluation of antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities of penicillium Islandicum and Aspergillus tamarii Ethyle acetate extracts. Pharmaceuticals 6, 2021–2039 (2016).

Khatiwora, E., Adsul, V. B., Kulkarni, M., Deshpande, N. & Kashalkar, R. Antibacterial activity of dibutyl phthalate: A secondary metabolite isolated from Ipomoea carnea stem. J. Pharm. Res. 5, 150–152 (2012).

Aparna, V. et al. Anti-inflammatory property of n‐hexadecanoic acid: structural evidence and kinetic assessment. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 80, 434–439. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-0285.2012.01418.x (2012).

de Rodríguez, D. J., García-Hernández, L. C., Rocha-Guzmán, N. E., Moreno-Jiménez,M. R., Rodríguez-García, R., Díaz-Jiménez, M. L. V., … Carrillo-Lomelí, D. A. Psacalium paucicapitatum has in vitro antibacterial activity. Industrial Crops Products 107, 489–498 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.05.025 (2017).

Beema Shafreen, R. M., Seema, S., Alagu Lakshmi, S., Srivathsan, A., Tamilmuhilan,K., Shrestha, A., Muthupandian, S. In vitro and in vivo antibiofilm potential of eicosane against Candida albicans. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 194, 4800–4816, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12010-022-03984-8, (2022).

Kim, S. & Kim, T. J. Inhibitory effect of Moringa oleifera seed extract and its Behenic acid component on Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. Antibiotics 14, 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14010019 (2024).

Salih, L., Eid, F., Elhaw, M. & Hamed, A. In vitro cytotoxic, antioxidant, antimicrobial activity and volatile constituents of Coccoloba peltata Schott cultivated in Egypt. Egypt. J. Chem. 64, 7157–7163. https://doi.org/10.21608/ejchem.2021.87688.4229 (2021).

Bailey, A., De Lucca, A. & Moreau, J. Antimicrobial properties of some erucic acid-glycolic acid derivatives. J. Am. Oil Chemists’ Soc. 66, 932–934. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02682611 (1989).

Umoh, R. A. et al. Isolation of a Lauryl alcohol (1-Dodecanol) from the antioxidant bioactive fractions of Justicia insularis (Acanthaceae) leaves. Nat. Prod. Commun. 20, 1934578X241297510. https://doi.org/10.1177/1934578X241297510 (2025).

Witkowska-Banaszczak, E. & Długaszewska, J. Essential oils And hydrophilic extracts from the leaves And flowers of Succisa pratensis moench. And their biological activity. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 69, 1531–1539. https://doi.org/10.1111/jphp.12784 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Al-Azhar University, Faculty of Science, Botany and Microbiology Department for supporting this study. The author also thanks Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R454), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, The author also thanks College of Pharmacy, Al-Farahidi University, Baghdad, Iraq for supporting this study.

Funding

The author also thanks Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R454), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.A; methodology, M.H.M., and A.M.A.; software, S.S., M.H.M., and A.M.A; validation, M.T.A., S.K. A., H.M.A., F.M.A., M.H.M., and A.M.A. ; formal analysis M.H.M., and A.M.A ; investigation, M.S.A., H.S.G., M.H. A., M.H.M., and A.M.A ; resources, S.S.,M.T.A., S.K. A., H.M.A., F.M.A., M.H.M., and A.M.A ; data curation, M.H.M., and A.M.A.; writing—original draft, M.S.A., H.S.G., M.H. A., M.T.A., S.K. A., H.M.A., F.M.A., M.H.M., and A.M.A.; writing—review & editing, S.S., M.H.M., and A.M.A ; supervision, M.H.M., and A.M.A ; project administration, M.H.M., and A.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Selim, S., Moustafa, M.H., Almuhayawi, M.S. et al. Phytochemical profiling and evaluation of antioxidant, anticancer, antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities of endophytic fungi isolated from Lavandula stricta. Sci Rep 15, 23734 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07627-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07627-w