Abstract

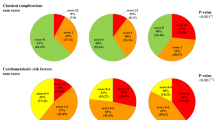

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a global health burden. Monitoring its determinants and incidence trends is important for identifying risk factors and projecting future health service needs. The Abu Dhabi Risk Study (ADRS) is a retrospective cohort study of 8699 participants in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (UAE), with an average follow-up period of 9.2 years. This study reports the prevalence of diabetes in this cohort, as well as the incidence of diabetes among the 6,772 participants who were diabetes-free at the start of the follow-up period in 2011–2013. Cox regression was used to develop a prediction model and identify significant determinants. Over the 12-year follow-up period, 643 individuals developed new diabetes, with an overall incidence of 7.4%. The prevalence of diabetes DM increased to 28.5%. Reaching 25.3% in females and 31.9% among males. Significant risk factors for developing new diabetes were a higher level of HBA1C, current smoking status at screening, and a higher level of eGFR. The model developed showed good performance in predicting new diabetes with a c-statistic of 0.837 (0.818–0.856), a sensitivity of 75.1%, and a specificity of 78.1%. Determinants of developing pre-DM included higher Diastolic Blood Pressure (DBP), total cholesterol, Random Blood Sugar (RBS), Body Mass Index (BMI), age, and lower High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL) levels. Gender and smoking status were not significant determinants for the diagnosis of prediabetes. The cumulative prevalence of prediabetes and diabetes is increasing steadily, with a plateau reached at 40 in the case of pre-DM and 60 with DM, and a decline with increasing age. The prevalence of diabetes in Abu Dhabi remains high. The Derived model is valuable for informing clinical practice and preventing diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes among United Arab Emirates nationals is among the highest in the world1. The latest reported prevalence was 21% among males and 23% among females, with a similarly high prevalence of its main risk factors, such as obesity2,3. Assessing the burden of diabetes and its risk factors is important due to their significant contribution to mortality, quality of life, and healthcare utilization1,4,5. Additionally, control of this increasing burden requires high-quality studies to inform healthcare decision-makers and patient care. An important area in such studies is the regional variation6 that may be influenced by factors such as healthcare system preparedness and responses toward prevention and management, aging, urbanization, culture, and physical inactivity across different countries and ethnicities7.

Cohort studies are particularly important in diabetes epidemiology, especially in the areas of prevention and treatment, as well as in understanding the differences among various populations. With accumulating evidence that diabetes mellitus can be prevented or delayed, the contributions of different preventive and management strategies to outcomes can only be shown in these types of studies. For example, healthier Lifestyles and the use of pharmacological interventions such as metformin were found to reduce the rate of progression to type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance, with lifestyle interventions being as effective as pharmacological treatment. Such interventions target multiple risk factors, but once stopped, the effects are not sustained8. Risk assessment to identify individuals with a higher risk of diabetes and tailoring strategies for the initiation of suitable and effective interventions requires large cohorts and diverse populations to increase the precision of interventions. Risk scores developed from research-based prediction models are key in assessing and identifying such patients9,10. They as well guide policy decisions in diabetes surveillance and prevention to decrease the progression of diabetes to complications, disability, and mortality.

The prevalence of diabetes is highest in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries at 25.45%, compared to non-GCC countries, which have a lower prevalence of 12.69%11. Incidence studies of diabetes in Abu Dhabi and the surrounding region are rare, even though diabetes research in the country is relatively robust. Therefore, assessing regional variations within the UAE or the surrounding areas is challenging. The few available studies have limitations, including small sample sizes, short follow-up durations, and a lack of community-based aspects12,13.

The United Arab Emirates is a rapidly developing country with a well-resourced healthcare system14. Strategies for the early detection and management of chronic diseases on a large scale have been implemented for many years. For example, the cardiovascular screening program, Weqaya, which started in 2008, could have one of the best screening coverages in the world and was designed to assess cardiovascular risk factors among the Abu Dhabi population. This study is part of a large retrospective cohort study, which includes a sample of the Weqaya screening participants from 2011 to 2013. Diabetes-free Abu Dhabi cardiovascular screening program participants were retrospectively evaluated for the incidence of diabetes, prediabetes, and risk factors studied.

Methods

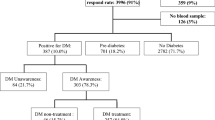

The Abu Dhabi Risk Study (ADRS) is a retrospective cohort study of 8699 participants in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (UAE), with an average follow-up period of 9.2 years. This study reports the prevalence, incidence, and risk factors of diabetes in this cohort, as well as the derivation of a prediction model for the risk of diabetes development over a 9.2-year follow-up period. The study methodology was described in detail in a related publication15. The participants were from Weqaya, a national screening program in Abu Dhabi3. This study cohort included 8699 United Arab Emirates nationals, nearly 2% of the total Abu Dhabi United Arab Emirates population in 2011. It was sampled from individuals who participated in the first Abu Dhabi population-wide cardiovascular screening program for adults aged 18 and older, Weqaya (prevention), between 2010 and 2013. From 12,752 with no missing values for the main variables, 8699 were randomly selected to have their charts reviewed 2023.

Data collected at baseline included demographic data, self-reported health indicators, including smoking status, physical activity, preexisting CVD (angina, heart attack, transient ischemic attack, stroke, other circulatory disorder), family history of premature cardiovascular disease (a first-degree relative with a heart attack or stroke before the age of 50 years), history of cardiovascular risk factors for diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia and whether participants were taking medication for these conditions. Anthropometric measures included waist and hip circumference, body mass index (BMI in kg/m2), and a single arterial blood pressure reading. A digital automatic blood pressure monitor measured blood pressure from the left arm with the patient relaxed and seated. Hematological parameters included non-fasting glucose (mmol/L), total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (mmol/L), glycosylated hemoglobin (HBA1C), vitamin D, and creatinine. The inclusion of the non-fasting glucose is a pragmatic approach in screening to improve the completion of the screening by participants. The Mean BP was calculated as (Systolic + 2*Diastolic)/3. Obesity was classified into three classes: I (30-34.9), II (35-39.9), and III (≥ 40)16. The glomerular filtration rate was calculated using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation17. Medications for diabetes risk factors were collected for hypertension and dyslipidemias. As well as aspirin use. There was no specification of which medications were used; instead, the use of blood pressure-lowering medications, statins, or aspirin. The dates and durations of statin and aspirin use were also collected.

-

At baseline, 8699 subjects from the national cardiovascular screening program of 2011–2013, with an average follow-up of 9.2 years (ranging from a minimum of 1 year to a maximum of 12 years), were eligible for enrollment if they were non-diabetic. The pre-diabetic definition was an HBA1C level of 5.7–6.4%. Diabetes was identified as HBA1C of > _6.4%, a documented diabetes diagnosis (entered by the treating physicians in the problem list within the EMR) or ICD code entered when prescribing diabetic medications. Participants were assessed retrospectively in 2023 for health outcomes. Age-adjusted prevalence for age-specific comparisons between countries utilized the population percentage in each 5-year age group in the new WHO World Standard population, based on the expected evolution of the world’s population age structure over the first quarter of the 21st century18. All participants had their eGFR determined. The method to determine the age-specific percentiles for the estimated glomerular filtration rate was the LMS method19. The resultant age and sex-specific GFR percentiles were derived from this cohort after excluding subjects with comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease, stroke, and cancer. Subjects were classified in appropriate eGFR percentiles according to age, sex, and eGFR.

Statistical analysis

Prediction models for diabetes were developed using Cox proportional hazards regression, with progression to diabetes as the endpoint. Patients were censored at the time of death or at their last HBA1C measurement if it was < 6.4%. Potential predictors included age, RBS, BMI, current smoking status, sex, HBA1C, mean BP, eGFR, HDL, and HTN. (Table 2) Every possible combination of variables was tested, as well as all potential interactions between these variables. For discrimination, the time-dependent area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was compared for the resulting prediction models.

SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 29 was used.

Results

The prevalence of DM at baseline was 22.2%, with 18.5% in females and 25.8% in males. The HBA1C was ordered based on routine care as per the physician’s decision and the patient’s agreement. Among the 6,772 diabetes-free subjects (3,537 females and 3,235 males), 643 developed new diabetes over the follow-up years, resulting in an overall incidence of 9.5%, with 317 (9.0%) females and 326 (10.0%) males over the 12-year follow-up period. The incidence of DM fluctuated throughout the years of follow-up (Appendix 1), with an increasing incidence from the 6th to the 9th year, peaking at 14.8% in the 7th year of follow-up.

. During the follow-up years, the prevalence increased to 28.5%, with 25.3% in females and 31.9% among males. The overall age-standardized prevalence rose from 18 to 23.7%.

The participant’s demographics at baseline are shown in Table 1. Smoking was less common (0.7%) among females than among males (20.9%). 65.5% of females had an HDL of more than 1.29 compared to 28.5% of males. Concerning cardiovascular health, 6.5% of males and 4.9% of females were under lipid-lowering therapy, whereas 38.4% of males and 33.6% of females had cholesterol levels more than 5.2. There were 36.0% and 28.8% of males with optimum and normal blood pressure, respectively, compared to 66.8% and 18.0% of females. Hypertension had been diagnosed in 11.3% of males compared to 6.7% of females. Obesity was slightly more prevalent among females, with 20.8% having class I (30-34.9) obesity, 9.5% having class II (35-39.9), and 5.3% being class III (≥ 40), compared to 20.2%, 6.6%, and 3.7%, respectively, among males.

HBA1C is the main determinant of new DM, with a nearly seven-fold increase in risk for each one-unit rise in HBA1C. A one-unit increase in Random glucose RBS had a 1.2% increase in the risk of DM, while the hazard of developing DM decreased by 0.403 for each one-unit rise in HDL. From multivariate Cox regression, for each one-year increase in age, the risk of developing DM increases by 1.03%, adjusted for other risk factors. Appendix 2.

Different percentiles of eGFR have varying effects, with the 3rd percentile showing a significant risk of developing DM. Interestingly, higher eGFR was found to be a significant risk factor for developing diabetes. An eGFR in the 97th percentile increased the risk of diabetes by 37.9%, with a hazard ratio of 1.379 (1.063–1.789) and a p-value of 0.016.

Smokers have a 1.425% increased risk, and obesity is a significant risk factor, with a 1.017% increase in risk with each one-unit increase in BMI. Mean blood pressure (BP) is another significant risk factor, with a 1.009% increase in risk for each one-unit mmHg increase in Mean BP. However, the hypertension was not statistically significant.

The DM hazard ratio steadily increases with increasing HBA1C. At the pre-DM cutoff level of 5.7, the HR is 10, doubles at 6, and triples at 6.5, the chosen cutoff point for DM, as shown in Appendix 3. Finally, although higher BMI was associated with a higher risk of progression to DM, as per Appendix 4, subjects with normal BMI and overweight also have high levels of HBA1C.

The model developed showed good performance with a c-statistic of 0.837 (0.818–0.856). The ROC is shown in Fig. 1 with a cutoff point identified for the hazard ratio of 2.06; it has a sensitivity of 75.1% and a specificity of 78.1%. HBA1C alone as a predictor of DM performance was lower than the model but close to it, with a c-statistic of 0.784 (0.761–0.807), Fig. 1. The hazard ratio’s cutoff for HBA1C, identified by the model, is 5.650, with a sensitivity of 68.6% and a specificity of 73.2%. In comparison, the c-statistics for using only random blood sugar as a predictor was 0.698 (0.672–0.723). Figure 1.

With regard to pre-DM, among non-diabetic patients, 804 did not do the HBA1C after screening, or it is not documented (17.7%), 803 in the non-pre-DM group. Based on the latest test, the mean HBA1C in the pre-DM group was 5.9, SD 0.2 (min 4.9 max 6.4), and in the non-pre-DM range group, it was 5.2, SD = 0.21 (min 2.8 max 5.7) among those with no pre-DM at screening, 14.45%. Interestingly, almost half, 44.1%, of those with pre-DM at screening reverted to normal values. Determinants of developing pre-DM were higher screening DBP, total cholesterol, RBS, BMI, and age, as well as lower levels of HDL Table 3. Gender and smoking status were not significant determinants for the diagnosis of prediabetes during follow-up.

Figure 2 is a scatter plot showing the cumulative prevalence of prediabetes and diabetes with age. It is increasing steadily, with a plateau reached at 40 years of age in the case of pre-DM and 60 with DM. After the plateau, there is a decline with increasing age.

Discussion

This study is the first longitudinal population-representative examination of diabetes incidence in an area considered among the highest in prevalence. Our estimate of prevalence for 2011 is close to the International Diabetes Federation’s (IDF) estimate of 18.8% in 2011 for the UAE20. With an increase in age-standardized prevalence from 18.8 to 23.7%, the problem of DM is worsening, underscoring the urgent need for comprehensive public health interventions in the region. The incidence is close to previously reported study in Abu Dhabi12. By taking proactive steps to address the underlying determinants of diabetes, it will be possible to mitigate its impact on population health and improve outcomes for individuals living with or at risk of developing the disease. These study results can inform the screening programs and the development of interventions for patients identified as being at high risk. Possible effective interventions could be targeted smoking cessation programs, lifestyle interventions focusing on weight management and diet, and earlier screening for individuals with high HbA1c, in this high-risk population. All programs must be supported by training for healthcare professionals and community awareness.

-

The model of prediction of progression from non-DM to DM derived from this study was excellent and would support the identification of high-risk patients as a tool for risk stratification, thereby facilitating personalized preventive strategies. The high c-statistic value suggests that our model has excellent discriminatory power in distinguishing between individuals who will develop diabetes mellitus (DM) and those who will not. This level of accuracy is particularly significant in the context of diabetes, where early identification of individuals at risk is crucial for targeting preventive measures. Compared to the commonly used diabetes prediction model, the American Diabetes Association’s Diabetes Risk Score, this study-derived model performed close to it with an AUC of 0.837, compared to the ADA Risk Score of 0.85–0.8721. Worth noting that the ADA tools were validated recently in Indonesia and Iran, and the AUC was 0.71 and 0.737, respectively22,23. Another example is the Canadian Diabetes Risk Assessment Questionnaire (CANRISK), which has an AUC of 0.7524. Additionally, there are increasing reports of the use of Machine learning in improving the performance of diabetes prediction tools, which could be a future opportunity for advances in this area25,26.

-

This study model’s ability to identify a broader range of significant risk factors compared to previous studies may enhance its utility in clinical practice27,28. Notably, it should facilitate a holistic approach to tailor interventions and preventive strategies based on each patient’s risk factors. Such a multidimensional approach not only enhances the accuracy of diabetes prediction but also provides valuable insights into the complex interplay of factors contributing to disease development.

-

Not surprisingly, advancing age emerged as a significant predictor of diabetes progression, with a 5.1% increase in risk for each one-year increase. Among potentially modifiable risk factors, higher levels of HBA1C, lower levels of HDL, higher BMI, higher DBP, and higher RBS were also associated with increased diabetes risk. These identified risk factors could be targeted through early intervention, focusing on lifestyle choices, including physical activity and dietary choices29,30. Recent studies have suggested that high HDL levels decrease insulin resistance16. In addition, HDL is known to have anti-inflammatory properties, which may reduce chronic inflammation, which is often thought to lead to insulin resistance31.

The high predictive value of HBA1C alone highlights the extent to which DM constitutes a chronic progressive disorder. It also highlights how to monitor this progression, as measuring HBA1C is a valid, simple test with minimal day-to-day fluctuation. It obviates a requirement for prior fasting and has superior predictive value compared to random blood glucose (RBG)32,33.

Another risk factor is random blood glucose (RBG). A single RBG ≥ 100 mg/dL was suggested as more strongly associated with undiagnosed diabetes, similar to this study. In fact, the cutoff value for the best sensitivity and specificity to detect DM in this study was 98, similar to their result, supporting the use of abnormal RBG values as a risk factor for diabetes that should be considered in screening guidelines34.

In this study, we found that high DBP carries a much higher risk of developing diabetes compared to high SBP. Other studies have linked both SBP and DBP to the progression of DM35. Nevertheless, other studies reported that insulin resistance (IR) is a risk factor for prehypertension and hypertension, and since IR is a state preceding diabetes, DBP could be a result of IR and not a risk factor for diabetes36. Insulin has a peripheral vasodilator, has an anti-natriuretic action in the distal renal tubules, and increases the activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system. These actions result in increased vasoconstriction and increased total circulating plasma volume, both of which play crucial roles in the pathophysiology of hypertension. This relationship requires further investigation to assess if DBP is a risk factor or an outcome of IR, which was not among the baseline variables in this study. This knowledge is important and will contribute to other research investigating whether the risk of diabetes can be modified by altering the identified risk factors.

Smoking increases the risk of DM by altering the body composition, insulin sensitivity, and pancreatic β-cell function37. This should add another item to the long list of arguments for healthcare professionals to address smoking prevention and cessation in their patients. Furthermore, the onset at a younger age was found to be associated with increased risk of worse cardiovascular outcomes38. This should urge healthcare professionals to focus on the younger age group for prevention and management options, as effective strategies already exist.

A higher level of eGFR is surprisingly a predictor of DM. This may suggest early renal complications of hyperglycemia, causing hyperfiltration39. No study has identified a higher eGFR percentile as a risk factor for diabetes, and this study is the first to demonstrate such a relationship. Although studies have pointed to the pathogenic and prognostic significance of glomerular hyperfiltration in the development and progression of diabetic kidney diseases39, only cross-sectional studies have shown an association between renal hyperfiltration and higher HBA1C levels, with no longitudinal studies investigating possible etiological factors40. Adding to the complexity in this area is the lack of consensus on the definition of renal hyperfiltration and its absence from clinical guidelines, despite increasing reports of its prognostic significance for mortality and metabolic and cardiovascular diseases41,42. This contributes to the challenges in determining potential mechanisms and warrants further investigation.

-

The high prevalence of pre-diabetes, particularly among younger age groups, is a significant concern, with 1 in 5 individuals aged 18 exhibiting pre-diabetic status. This is higher than the prevalence in the United States, which was 11.1% among adolescents and 15.8% among young adults33,43,44. This underscores the importance of targeted preventive strategies, as early intervention during the pre-diabetic stage can significantly mitigate the risk of progression to diabetes. Over 12 years, approximately half of pre-diabetic individuals maintained their status, similar to Paprott et al., study45. Only 14.1% of the study subjects transitioned to pre-diabetes from a normal glycemic state. These findings highlight the dynamic nature of pre-diabetes and the potential for intervention to influence disease trajectories46,47. Additionally, Olson et al., compared HBA1C and oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT), and the prevalence was underestimated with HBA1C, suggesting a limitation justifying future research33.

The drop in the prevalence of pre-DM later in life is probably due to progression to DM or reverting to normal glycemia. The former is more likely, as DM prevalence in relation to age has a similar trend. Also, the drop in the prevalence of DM later in life may be due to a higher-risk population getting older, replacing the older population. Older adults live healthier lives, engage in more physical activity, and have healthier diets. Another possibility is increased mortality among diabetics, but this is not confirmed by any study47,48,49.

The data collected in this study enabled the evaluation of potential risk factors, which had not been previously assessed in such a large cohort over a long duration of follow-up. Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. Firstly, the study’s retrospective design may introduce bias and might limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the reliance on electronic health records for data collection may lead to incomplete or unstandardized information. Moreover, the study’s focus on the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, UAE, may limit its relevance for other populations with different demographic and socio-economic profiles. Although this study contributes to filling a knowledge gap on diabetes risk factors in the region, particularly in the UAE, future studies that include other ethnicities, social determinants of health, and a prospective design will add to the understanding of possible understudied risk factors.

Conclusion

This study provides critical insights into the incidence and prediction of diabetes in the Emirate of Abu Dhabi, UAE, highlighting the urgent need for comprehensive public health interventions. By addressing the identified risk factors and leveraging predictive modeling, clinicians and policymakers can work towards mitigating the impact of the diabetes epidemic and enhancing health outcomes in the region. However, further research is needed to validate our findings and investigate additional factors that contribute to diabetes risk and progression.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study cannot be shared openly due to restrictions from the institution, Seha Clinics. Data availability is restricted due to institution policies. Latifa Baynouna Alketbi (latifa.mohammad@gmail.com) to be contacted regarding this request.

References

Organization, W. H. The top 10 causes of death. (2020). Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death

Baynouna, L. M. et al. High prevalence of the cardiovascular risk factors in Al-Ain, united Arab emirates. An emerging health care priority. Saudi Med. J. 29, 1173–1178 (2008).

Hajat, C., Harrison, O. & Al Siksek, Z. Weqaya: a population-wide cardiovascular screening program in Abu dhabi, united Arab Emirates. Am. J. Public. Health. 102, 909–914 (2012).

Al Marzooqi, F. M. A., Al Murri, S. G. & BaynounaAlKetbi Evaluation of health-related quality of life in patients with diabetes in different care settings a cross sectional study in alain, Uae. (2021).

Johan Östgren, C., Engström, S., Heurgren, M. & Borgquist, L. Healthcare utilization is substantial for patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care: a patient-level study in a Swedish municipality. EJGP 12, 83–84 (2006).

Hamoudi, R. et al. Prediabetes and diabetes prevalence and risk factors comparison between ethnic groups in the united Arab Emirates. Sci. Rep. 9, 17437 (2019).

Danaei, G. et al. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2·7 million participants. Lancet 378, 31–40 (2011).

Gillies, C. L. et al. Pharmacological and lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 334, 299 (2007).

Li, C-I. et al. Prospective validation of American diabetes association risk tool for predicting pre-diabetes and diabetes in taiwan–taichung community health study. PloS One. 6, e25906 (2011).

Zhang, H. Y. et al. Establishing a noninvasive prediction model for type 2 diabetes mellitus based on a rural Chinese population. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. [Chin J. Prev. Med]. 50, 397–403 (2016).

Meo, S. A., Usmani, A. M. & Qalbani, E. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the Arab world: impact of GDP and energy consumption. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 21, 1303–1312 (2017).

Regmi, D., Al-Shamsi, S., Govender, R. D. & Al Kaabi, J. Incidence and risk factors of type 2 diabetes mellitus in an overweight and obese population: a long-term retrospective cohort study from a Gulf state. BMJ Open. 10, e035813 (2020).

Shieb, M., Koruturk, S., Srivastava, A. & Mussa, B. M. Growth of diabetes research in united Arab emirates: current and future perspectives. Curr. Diabetes. Rev. 16, 395–401 (2020).

Expatica. The health care system in the United Arab Emirates. Expatica. May (2025). Available from: https://www.expatica.com/ae/healthcare/healthcare-basics/the-healthcare-system-in-the-united-arab-emirates-71767/. last accessed.

AlKetbi, L. B. et al. Disease risk score derivation and validation in Abu dhabi, united Arab emirates: A retrospective cohort study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 13, e035930 (2024).

2 TSR. The Surveillance of Risk Factors Report Series (SuRF). (2005). Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43190/9241593024_eng.pdf. last accessed May 2025.

Foundation, N. K. CKD-EPI creatinine equation. (2023). Available from: https://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/gfr_calculator/formula. last accessed May 2025.

Ahmad, O. B. et al. Age standardization of rates: a new WHO standard. GPE Discussion Paper Series, 31. (2001). Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/gho-documents/global-health-estimates/gpe_discussion_paper_series_paper31_2001_age_standardization_rates.pdf. last accessed May 2025.

Cole, T. J. The LMS method for constructing normalized growth standards. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 44, 45–60 (1990).

Federation, I. D. Diabetes Atlas. United Arab Emirates Diabetes report 2000–2045. (2024). Available from: https://diabetesatlas.org/data/en/country/208/ae.html. last accessed May 2025.

Lindström, J. & Tuomilehto, J. The diabetes risk score: a practical tool to predict type 2 diabetes risk. Diabetes Care. 26, 725–731 (2003).

Harbuwono, D. S., Mokoagow, M. I., Magfira, N. & Helda, H. ADA Diabetes Risk Test Adaptation in Indonesian Adult Populations: Can It Replace Random Blood Glucose Screening Test. J Prim Care Community Health.

Asgari, S. et al. The external validity and performance of the no-laboratory American diabetes association screening tool for identifying undiagnosed type 2 diabetes among the Iranian population. Prim. Care Diabetes. 14, 672–677 (2020).

Robinson, C. A., Agarwal, G. & Nerenberg, K. Validating the CANRISK prognostic model for assessing diabetes risk in canada’s multi-ethnic population. Chronic Dis. Inj Can. 32, 19–31 (2011).

Choi, S. G. et al. Comparisons of the prediction models for undiagnosed diabetes between machine learning versus traditional statistical methods. Sci. Rep. 13, 13101 (2023).

Stiglic, G. & Pajnkihar, M. Evaluation of major online diabetes risk calculators and computerized predictive models. PLoS One. 10, e0142827 (2015).

Al-Lawati, J. A. & Tuomilehto, J. Diabetes risk score in oman: a tool to identify prevalent type 2 diabetes among Arabs of the middle East. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 77, 438–444 (2007).

Sulaiman, N. et al. Diabetes risk score in the united Arab emirates: a screening tool for the early detection of type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMJ Open. Diabetes Res. Care. 6, e000489 (2018).

Muscella, A., Stefàno, E. & Marsigliante, S. The effects of exercise training on lipid metabolism and coronary heart disease. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 319, H76–H88 (2020).

Stanton, K. M. et al. Moderate- and High-Intensity exercise improves lipoprotein profile and cholesterol efflux capacity in healthy young men. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 11, e023386 (2022).

Laws, A. & Reaven, G. M. Evidence for an independent relationship between insulin resistance and fasting plasma HDL-cholesterol, triglyceride and insulin concentrations. J. Intern. Med. 231, 25–30 (1992).

Nagarathna, R. et al. Distribution of glycated haemoglobin and its determinants in Indian young adults. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 159, 107982 (2020).

Olson, D. E. et al. Screening for diabetes and pre-diabetes with proposed A1C-based diagnostic criteria. Diabetes Care. 33, 2184–2189 (2010).

Bowen, M. E., Xuan, L., Lingvay, I. & Halm, E. A. Random blood glucose: a robust risk factor for type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100, 1503–1510 (2015).

Emdin, C. A., Anderson, S. G., Woodward, M. & Rahimi, K. Usual blood pressure and risk of New-Onset diabetes: evidence from 4.1 million adults and a Meta-Analysis of prospective studies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 66, 1552–1562 (2015).

Castro, L. et al. Association of hypertension and insulin resistance in individuals free of diabetes in the ELSA-Brasil cohort. Sci. Rep. 13, 9456 (2023).

Maddatu, J., Anderson-Baucum, E. & Evans-Molina, C. Smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes. Transl Res. 184, 101–107 (2017).

Echouffo-Tcheugui, J. B. et al. An Early-Onset subgroup of type 2 diabetes: A multigenerational, prospective analysis in the Framingham heart study. Diabetes Care. 43, 3086–3093 (2020).

Tonneijck, L. et al. Glomerular hyperfiltration in diabetes: mechanisms, clinical significance, and treatment. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 28, 1023–1039 (2017).

Hu, W., Hao, H., Yu, W., Wu, X. & Zhou, H. Association of elevated glycosylated hemoglobin A1c with hyperfiltration in a middle-aged and elderly Chinese population with prediabetes or newly diagnosed diabetes: a cross-sectional study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 15, 47 (2015).

Penno, G. et al. Renal hyperfiltration is independently associated with increased all-cause mortality in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. Diabetes Res. Care. 8, e001481 (2020).

Park, M. et al. Renal hyperfiltration as a novel marker of all-cause mortality. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26, 1426–1433 (2015).

Andes, L. J., Cheng, Y. J., Rolka, D. B., Gregg, E. W. & Imperatore, G. Prevalence of prediabetes among adolescents and young adults in the united states, 2005–2016. JAMA Pediatr. 174, e194498 (2020).

Paprott, R., Scheidt-Nave, C. & Heidemann, C. Determinants of change in glycemic status in individuals with prediabetes: results from a nationwide cohort study in Germany. J. Diabetes Res. 2018, 5703652 (2018).

Park, K. S. & Hwang, S. Y. Lifestyle-related predictors affecting prediabetes and diabetes in 20-30-year-old young Korean adults. Epidemiol. Health. 42, e2020014 (2020).

Bennasar-Veny, M. et al. Lifestyle and progression to type 2 diabetes in a cohort of workers with prediabetes. Nutrients 12, 1538 (2020).

Rooney, M. R. et al. Risk of progression to diabetes among older adults with prediabetes. JAMA Intern. Med. 181, 511–519 (2021).

Koyama, A. K. et al. Progression to diabetes among older adults with hemoglobin A1c-Defined prediabetes in the US. JAMA Netw. Open. 5, e228158 (2022).

Veronese, N. et al. Risk of progression to diabetes and mortality in older people with prediabetes: the english longitudinal study on ageing. Age Ageing. 51, afab222 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LBK and NN conceptualized and analyzed data. LBK, MS, RK, MD, NA wrote the manuscript; all other co-authors collected data and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Al Ain Human Ethics Committee, approval number 13/58, and Ambulatory Healthcare Services IRB 19-2022. All methods were carried out under relevant guidelines and regulations. The authors confirm that the study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Informed consent

Informed consent was waived by the the Al Ain Human Ethics Committee and Ambulatory Healthcare Services IRB as the study was designed for retrospective data gathered as part of patient care and anonymized at analysis.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Baynouna AlKetbi, L.M., AlKetbi, R., AlShamsi, M.S. et al. Incidence and predictors of type 2 diabetes mellitus in a population-based cohort study in Abu Dhabi. Sci Rep 15, 23639 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07631-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07631-0