Abstract

The distribution of body fat may influence fracture risk, yet the association between DXA-derived regional fat and fragility fractures remains unclear. We analysed 36,235 patients undergoing lumbar spine and femoral DXA scans from June 2004 to February 2024, categorizing abdominal, left hip, and right hip fat percentages into tertiles (low, medium and high). Multivariable logistic regression models were fit with the dependant variable being hip or any fragility fracture and the independent variable being the binary regional body composition groups. All results were adjusted for FRAX clinical factors where we found that the lowest tertile of abdominal fat was associated with reduced odds of any fracture (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.74–0.82), while the highest tertile was linked to increased odds (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.17–1.29) but was not associated with hip fracture. For left hip fat, the lowest tertile was linked to decreased odds of any fracture (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.58–0.64), and the highest tertile showed increased odds of any fracture (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.50–1.65) and hip fracture (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.07–1.63). Similarly, the right hip fat lowest tertile was associated with reduced odds of hip fracture (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.58–0.93) and any fracture (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.59–0.66), while the highest tertile was linked to increased odds of hip fracture (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.37–2.07) and any fracture (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.52–1.67). Our results suggest DXA derived regional body composition may be a novel predictor of both hip and any fragility fractures with further research needed to validate our findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis is defined as a reduction in bone mineral density (BMD) 2.5 standard deviations below that of a healthy young adult population1. Clinically, it remains asymptomatic until a fragility fracture occurs, hence early identification and stratification of at risk populations remains a central part of osteoporosis management1. Fracture risk calculators such as FRAX and QFracture are both commonly used in clinical practice and combine multiple known risk factors for fracture including bone mineral density. FRAX has recently begun working on a updated calculator called FRAXPlus which now includes additional risk factors including type 1 diabetes, and previous osteoporotic fracture as an example2. However advanced body composition techniques beyond body mass index (BMI) have yet to be integrated into either of these tools to improve the accuracy of their calculations2.

BMI is defined as weight over height squared and is very easy to calculate in clinical practice. High BMI has been associated with increases in BMD and a decrease in fracture risk and vice versa for low BMI3. However in fracture risk calculators BMI is largely dependent on BMD and its predictive value on its own is limited including in obese populations who tend to fracture at normal BMDs3. Furthermore, BMI is a crude measure that does not reflect true body composition (fat mass versus lean mass) and is inadequate for detecting body composition disorders like sarcopenia, sarcopenic obesity, and osteosarcopenia, all of which are increasingly recognized as important factors in fracture risk4. Hence approaches beyond BMI that are sensitive to changes in body composition are needed to improve the accuracy of fracture risk calculators.

While high BMI is generally associated with increased bone density, the same does not hold true for high levels of adipose tissue5. Research suggests that excessive adipose tissue exerts complex and often detrimental effects on bone health. High levels of adipose tissue have been linked to chronic low-grade inflammation6, elevated adipokine levels7, and vitamin D deficiency—all of which impair bone quality and increase fracture risk8. Furthermore the biomechanical effects of high levels of adiposity have been associated with an increased risk of falls9, due to shifting the body’s centre of mass, which can increase postural instability and predispose individuals to falls and fractures10. In addition to these mechanisms between adiposity and fragility fractures the distribution of adipose tissue is also said to influence both bone density and fracture risk11.

Two primary clinical phenotypes based on fat distribution are often discussed in the literature: the “apple” phenotype, characterized by elevated levels of intra-abdominal (visceral) fat and the “pear” phenotype which is associated with peripheral fat storage in areas such as the hips and thighs12. Intrabdominal Visceral fat has been shown to correlate with reduced bone density and an increased risk of fracture, with many studies employing waist-to-hip ratios and waist circumference as proxies for fat distribution13. However, when studies have used dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) derived abdominal fat mass this has shown mixed results14,15. Conversely, while gynoid or peripheral obesity may be linked to a higher risk of falls16, its direct relationship with fracture risk remains to be clearly established. Hence further research is needed to clearly elaborate how DXA derived regional fat distribution affects fracture risk.

DXA is a highly accurate way of measuring body composition, with a full body DXA scan being the gold standard way of measuring body composition17, though this is not routinely performed in clinical practice18. However many patients who undergo diagnostic work up for osteoporosis will have bilateral femoral and lumbar spine DXA scans19 which also gives us body composition data at said sites20, though this information is not reported on the scan report, though stored in the systems database. Hence using this data could be a novel way of considering regional body fat data in fracture risk calculators beyond simple measures such as the waist-to-hip ratio.

Aims

The aim of this study is to assesses whether DXA derived regional adiposity is associated with hip or any major fragility fracture.

Methods

Data collection

Patients were referred from primary and secondary care to our DXA scanner in the northwest of England between June 2004 and February 2024. Our regional scanner serves a population of 365,000 patients and sees roughly 2,300 patients per year. Two scanners have been used during this period: the GE Lunar Prodigy (2004–2019) and, more recently, the GE Lunar iDXA (2019–present). Cross-calibration was conducted at the time of system transition using scan phantoms to ensure continuity and accuracy of measurements. Routine quality control is performed weekly also using scan phantoms to maintain measurement precision. All referrals are vetted by staff prior to acceptance.

Typically, patients undergo a combined scan of the lumbar spine and bilateral femoral regions, which is standard practice at our regional scanner. The lumbar spine scan includes the L1–L4 region while the femoral scans included the femoral head, neck, wards triangle, trochanters, and part of the shaft. These scans provided both bone density and compositional data for these sites. Bone mineral density was reported as a T-score. For compositional data, the DXA scan measured lean mass, fat mass, and calculated the local fat percentage at each site.

Fracture history was obtained by the technician to determine whether the patient had experienced a fragility fracture, defined as a fracture resulting from a fall from standing height or less over the age of 50. The technician verified both the mechanism and anatomical site of each reported fracture prior to data entry.

Demographic and FRAX risk factors were collected via a standardised questionnaire. Patients were asked regarding the presence of fracture risk factors which was then inputted by the technician into the system. Risk factors included whether the patient was a current smoker, was currently taking glucocorticoids (defined as > 5 mg per day of prednisolone or equivalent for > 3 months at the time of the appointment as per FRAX), or consumed excess alcohol (> 3 units per day), had rheumatoid arthritis or had a parental history of fragility fracture.

All data were stored in a SQL server where data was then extracted and synthesised to form our database for analysis. Full ethical approval for pseudonymized data extraction in the absence of informed consent was obtained from the local ethics committee (NRES Committee Northwest Preston, project number 14/NW/1136).

Data analysis

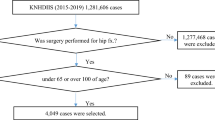

Only scanned patients who underwent combined bilateral femoral and abdominal scans were included in the analysis. Baseline characteristics were first compared between the fractured and non-fractured populations. Comparative statistics were used including the student’s t-test for normally distributed continuous data and Pearson’s chi-squared test for categorical data.

To allow comparison, fat percentages at the abdomen (FPA), left hip (FPLH), and right hip (FPRH) were first stratified into tertiles, with tertile 1 representing the lowest fat percentage and tertile 3 the highest. Next, binary groups were created from the tertiles; for example, patients in the lowest tertile of abdominal fat were coded as a one while the rest of the population was coded as a zero. This was repeated for all other tertiles at each anatomical sites creating 9 binary groups in total, which was the foundation of our statistical analysis. We decided to use this approach versus using continuous variables for fat percentages to allow for ease of interpretation as well as effectively handling any non-linearity which may have been present.

Each of the nine body composition groups was then used as the independent variables in separate multivariate logistic regression models to assess associations with femoral (hip) fractures and with any fragility fracture. Separate models were employed to avoid collinearity and ensure numerical stability. The definition of ‘any fragility fracture’ encompassed major osteoporotic sites (spine, humerus, wrist), as well as tibial, fibular, and ankle fractures. Hip fractures were analysed independently due to their disproportionately high associated morbidity and mortality21.

All models were adjusted for the same confounders: gender, age, current smoking, excessive alcohol use (> 3 units/day, per FRAX), steroid therapy (> 5 mg/day for > 3 months), rheumatoid arthritis, personal and family history of fragility fractures, and left femoral total T-score. A Bonferroni-corrected p-value of 0.017 (0.05/3) was applied to account for the three groups analysed per anatomical site. STATA version 18 was used in our analysis.

Results

Demographics

A total of 36,235 patients were included in the analysis, of whom 14,342 reported a fragility fracture including 383 femoral fractures. The mean (SD) age of all patients was 65.7 (12.9) years, height was 162.3 (8.6) cm, weight was 71.6 (16.6) kg, and BMI was 27.1 (5.7) kg/m2. The mean left femoral T-score for all patients was − 1.0 (1.3).

Patients reporting fragility fractures were older (66.0 vs. 65.3 years, P < 0.001) and more often female (84.0% vs. 83.0%, P = 0.013). They were slightly shorter (162.1 vs. 162.4 cm, P = 0.003), while weight and BMI did not differ significantly. Smoking rates were comparable between groups, but higher alcohol consumption (> 3 units/day) was more common among those with fractures (8.0% vs. 6.6%, P < 0.001). Glucocorticoid use (6.1% vs. 11.6%, P < 0.001) and rheumatoid arthritis (5.5% vs. 6.9%, P < 0.001) were less frequent in the fracture group. Family history of fracture showed no significant difference. DXA T-scores were significantly lower in fractured patients at the left femur (− 1.2 vs. − 0.75), right femur (− 1.2 vs. − 0.77), and lumbar spine (− 0.8 vs. − 0.2) (all P < 0.001). These results can be seen in Table 1.

The mean fat percentages in the full cohort were 30.45% (SD 7.01) at the left femur, 29.93% (6.93) at the right femur, and 31.66% (10.72) at the abdomen. Patients with fractures had significantly higher fat percentages at the left femur (31.6% vs. 29.7%), right femur (31.0% vs. 29.2%), and abdomen (32.1% vs. 31.4%) (all P < 0.001). Tertiles for fat distribution were defined as abdominal fat ≤ 27.42%, 27.43–37.44%, and ≥ 37.44%; left femoral fat ≤ 27.34%, 27.35–33.40%, and ≥ 33.40%; right femoral fat ≤ 26.83%, 26.84–32.79%, and ≥ 32.79%. These cutoffs can also be seen in Table 2.

Primary analysis results

Our primary analysis revealed significant associations between regional fat distribution and the odds of fractures. For abdominal fat, patients in Tertile 1 (lowest) had significantly lower odds of experiencing any fragility fractures (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.74–0.82, P < 0.001), while those in Tertile 3 (highest) had higher odds (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.17–1.29, P < 0.001). This relationship between lower fat levels and reduced odds of any fracture was also observed for the left femoral region (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.58–0.64, P < 0.001) and right femoral region (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.59–0.66, P < 0.001). Conversely, increased odds were seen in the highest tertile of regional fat and any fragility fracture for both the left femoral (OR 1.57, 95% CI 1.50–1.65, P < 0.001) and right femoral fat percentages (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.52–1.67, P < 0.001). These results can be seen in Tables 3, 4 and 5.

Interestingly, for hip fractures, only high fat percentages (tertile 3) in the femoral regions were associated with increased odds of hip fracture. Specifically, elevated left femoral fat (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.07–1.63, P = 0.010) and right femoral fat (OR 1.68, 95% CI 1.37–2.07, P < 0.001) were linked to higher odds of hip fractures. The lowest tertile of right femoral fat was associated with decreased odds of hip fracture (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.58–0.93, P = 0.011). No other significant findings were seen for between regional body composition and hip fractures. These results can also be seen in Tables 3, 4 and 5.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is one of the first to explore how hip fat percentage affects fragility fractures. While previous studies often look at abdominal fat13, the hip sites have seldom been explored in relation to fragility fractures. Our findings provide further insight into the role of regional fat deposition and its potential contribution to fracture risk.

Our analysis revealed compositional differences between fractured and non-fractured populations, with height being the only significantly different anthropometric variable—fractured patients were shorter. Surprisingly, neither weight nor BMI differed significantly between the groups. This contrasts with previous research that has highlighted associations between lower weight22,23, reduced BMI3, and fragility fractures. However, despite the lack of significance in weight and BMI, regional fat was notably higher in the fracture group, though the difference was relatively small in our univariate analysis. However, we hypothesise this could be the case given most of our patient group were homogenous given the fact they were all at-risk for osteoporosis. More heterogenous populations may have had larger difference in regional body composition between those reporting a fragility fracture versus those not reporting one. However this does however underscore a key limitation of BMI, which may not adequately capture body composition differences between fractured, and none fractured individuals that are important to fracture risk. This is especially problematic in elderly at risk populations who often undergo complex compositional changes including increasing adiposity and a reduction in muscle mass24.

In our primary analysis for any fragility fracture, we found that patients in the highest tertile of fat at all anatomical sites had significantly increased odds of any fractures, with the peripheral regions (hips) showing higher odds than centrally. Conversely, patients in the lowest tertile of fat had reduced odds of any fractures. Importantly, these associations were independent of known confounders such as age, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and BMD, further strengthening the robustness of our findings. Our findings could suggest that regional body fat could be an important independent factor associated with fragility fractures.

Several biological mechanisms could explain these results. Higher abdominal fat may alter a person’s centre of gravity10, increasing the risk of falls and fractures. This is supported by previous research showing that patients with high abdominal fat are more likely to be dynapenic and have an increased falls risk25,26,27. Hence our abdominal fat measurement may have captured this association.

Regarding hip fat as a predictor of any fracture it could be possible that patients with high levels of hip fat could have a reduction in the quality of gluteal muscles due to fatty infiltration28 which could impair both balance and stability29. Conversely, individuals with lower gluteal fat levels may have higher lean muscle mass, providing better physical control and protection against fractures. These findings emphasize the need for further research to better understand how fat distribution impacts muscle quality and affects both falls and subsequent fracture risk.

When focusing specifically on hip fractures, our analysis found a strong association between high hip fat and hip fracture. Interestingly there was no association found between abdominal fat and hip fractures. This does support the study conducted by Nguyen et al. which also looked at DXA derived abdominal fat as a predictor of hip fracture and concluded the relationship was likely to be modest at best14. We agree with this and believe that measuring hip fat may be a better way of predicting hip fracture. This could be the case as high hip fat would precipitate instability due to a reduction in gluteal muscle quality with high fat potentially not providing the cushioning effect which is often described in the literature30. Further research is needed with prospective cohorts to corroborate the association we have seen.

Given that high hip fat may mean a reciprocal decrease in muscle mass locally31, it would be interesting to know whether these patients are also sarcopenic or sarcopenic obese. This approach could be an indirect way of evaluating these patients for both body composition disorders in fracture risk calculators. Further research correlating regional body fat composition to accepted definitions of sarcopenia would be useful in elucidating its diagnostic utility in identifying these compositional disorders.

Additionally, it remains important to assess whether fat percentage from both hips is required to predict fragility fractures, or if a single hip measurement suffices. Prior studies suggest lower limb dominance affects BMD, with the non-dominant hip typically showing lower BMD values32. In our cohort, the difference in fat percentage between left and right femurs among fractured vs non-fractured individuals was modest (0.6%), with slightly higher fat on the left side. Furthermore, given the 95% confidence intervals in our multivariable models also overlapped when assessing both any fracture and hip fractures, this suggests that the odds from both hip were relatively similar. However, given that leg dominance influences BMD32, it may be hypothesised that it could affect regional body composition and fracture risk, though further research is needed to confirm this. Further research is ultimately needed to clarify the influence of hip dominance and regional compositional asymmetries on fracture risk.

We also believe that our findings also challenge the conventional “apple” (abdominal fat) and “pear” (hip fat) understanding of body composition and associated measurements including the waist to hip ratio (WHR) and waist circumference (WC). While previous studies have associated higher intra-abdominal fat with increased fracture risk13, these studies often rely on indirect measures, such as the WC or WHR, which generally suggest that peripheral fat may be protective. In contrast, our results imply that excessive peripheral fat, particularly in older adults, may be associated with fragility fractures including hip fractures specifically. Further research is warranted to explore the relationship between regional fat, waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and whether direct measurements of regional fat provide a more accurate reflection of fat distribution and its clinical implications including fracture risk.

One of the key unresolved questions raised by our study is whether high regional fat precedes fractures, or if fractures themselves lead to compositional changes over time. Due to the cross-sectional design of our study, we cannot establish causality, but we hypothesize that increased fat may contribute both to initial fractures and to subsequent fractures. Longitudinal studies are needed to clarify the directionality of this relationship and to determine whether regional fat could serve as an early marker of fracture risk.

Finally, while our study used arbitrary cut-offs for regional body fat, generating reference data for normal ranges of regional fat percentages could improve fracture risk prediction in this population. Establishing these normative data would allow for more accurate identification of patients at risk for fractures.

Strengths and limitations

This study is limited by its cross-sectional design, which prevents the evaluation of temporal relationships between regional fat distribution and fracture risk. Consequently, it remains unclear whether increased adiposity precedes fractures or results from them. Furthermore, the study population was also relatively homogeneous, comprising primarily Caucasian individuals at elevated risk for osteoporosis, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to the general population. Additionally, some participants may have been referred following a fracture event, introducing potential confounding by indication. We were also unable to determine the duration of exposure to fracture-related risk factors, which may have influenced the observed associations. Finally, the study is subject to potential recall and sampling biases, which could affect the validity of the results.

Our study is strengthened by large number of patient data we analysed, as well as the utilisation of routinely collected health data for regional body composition, which would not add any extra burden which mimics current clinical practice. All our patients underwent DXA scanning, the gold standard for both BMD assessment as well as fat mass data. Furthermore, we have analysed our results by looking at the more clinically useful outcome of fragility fractures as opposed to BMD.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated that there was no statistically significant difference in BMI between fractured and non-fractured patients; however, patients with fractures exhibited slightly higher adiposity across all regional sites we analysed. In terms of fragility fractures, low regional adiposity was associated with decreased odds of any fracture, while high regional adiposity was associated with increased odds of any fracture. Specifically, for hip fractures, only elevated left and right hip fat were associated with an increased odds of fracture. We hypothesize that regional fat, particularly at the hips, may serve as a novel predictor of fracture risk and could be biomechanically relevant with its relationship to falls risk and instability. However, further research is needed to validate our findings and hypotheses.

Data availability

Data can be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Akkawi, I. & Zmerly, H. Osteoporosis: Current concepts. Joints 6(2), 122–127 (2018).

El Miedany, Y. FRAX: Re-adjust or re-think. Arch. Osteoporos. 15(1), 150 (2020).

De Laet, C. et al. Body mass index as a predictor of fracture risk: A meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 16(11), 1330–1338 (2005).

Curtis, M., Swan, L., Fox, R., Warters, A. & O’Sullivan, M. Associations between body mass index and probable sarcopenia in community-dwelling older adults. Nutrients 15(6), 1505 (2023).

Jain, R. K. & Vokes, T. Visceral adipose tissue is negatively associated with bone mineral density in NHANES 2011–2018. J. Endocr. Soc. 7(4), 008 (2023).

Lumeng, C. N. & Saltiel, A. R. Inflammatory links between obesity and metabolic disease. J. Clin. Invest. 121(6), 2111–2117 (2011).

Hou, J. et al. Obesity and bone health: A complex link. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 600181 (2020).

Chen, R. & Armamento-Villareal, R. Obesity and skeletal fragility. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 109(2), e466–e477 (2024).

Neri, S., Oliveira, J., Dario, A., Lima, R. & Tiedemann, A. Does obesity increase the risk and severity of falls in people aged 60 years and older? A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75(5), 952–960 (2020).

Del Porto, H., Smith, D. & Reed-Jones, R. Biomechanical effects of obesity on balance. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 5(4), 301–320 (2012).

Zhu, X. W. et al. General and abdominal obesity operate differently as influencing factors of fracture risk in old adults. iScience 25(6), 104466 (2022).

Alser, M. & Elrayess, M. A. From an apple to a pear: Moving fat around for reversing insulin resistance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 21 (2022).

Sadeghi, O., Saneei, P., Nasiri, M., Larijani, B. & Esmaillzadeh, A. Abdominal obesity and risk of hip fracture: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Adv. Nutr. 8(5), 728–738 (2017).

Nguyen, N. D., Pongchaiyakul, C., Center, J. R., Eisman, J. A. & Nguyen, T. V. Abdominal fat and hip fracture risk in the elderly: The Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 6(1), 11 (2005).

Machado, L. G. et al. Visceral fat measured by DXA is associated with increased risk of non-spine fractures in nonobese elderly women: A population-based prospective cohort analysis from the São Paulo Ageing & Health (SPAH) Study. Osteoporos Int. 27(12), 3525–3533 (2016).

Neri, S. G. Body fat distribution in obesity and the association with falls: A cohort study of Brazilian women aged 60 years and over. Maturitas 139, 64–68 (2020).

Shepherd, J. A., Ng, B. K., Sommer, M. J. & Heymsfield, S. B. Body composition by DXA. Bone 104, 101–105 (2017).

Marra, M. et al. Assessment of body composition in health and disease using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) and dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA): A critical overview. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2019, 3548284 (2019).

Slart, R. H. J. A. et al. Updated practice guideline for dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 52(2), 539–563 (2025).

Covey, M. K., Berry, J. K. & Hacker, E. D. Regional body composition: Cross-calibration of DXA scanners–QDR4500W and Discovery Wi. Obesity (Silver Spring) 18(3), 632–637 (2010).

Mariconda, M. et al. The determinants of mortality and morbidity during the year following fracture of the hip: A prospective study. Bone Joint J. 97(3), 383–390 (2015).

Ensrud, K. E. et al. Body size and hip fracture risk in older women: a prospective study. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Am. J. Med. 103(4), 274–280 (1997).

Cummings, S. R. et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 332(12), 767–773 (1995).

Ponti, F. et al. Aging and imaging assessment of body composition: From fat to facts. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 10, 861 (2019).

Máximo, R. O. et al. Abdominal obesity, dynapenia and dynapenic-abdominal obesity as factors associated with falls. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 23(6), 497–505 (2019).

Lv, D., Shen, S. & Chen, X. Association between dynapenic abdominal obesity and fall risk in older adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 17, 439–445 (2022).

Smith, L. et al. Dynapenic abdominal obesity increases risk for falls among adults aged ≥ 50 years: A prospective analysis of the Irish longitudinal study on ageing. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 79, 1 (2024).

Pacicco, T. et al. Pelvic muscle size and myosteatosis: Relationship with age, gender, and obesity. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging 29(2), 155–162 (2019).

Davis, D. L. et al. Gluteal muscle fatty infiltration, fall risk, and mobility limitation in older women with urinary incontinence: A pilot study. Skeletal Radiol. 52(1), 47–55 (2023).

Pana, T. A. et al. Body fat percentage and the long-term risk of fractures. The EPIC-Norfolk prospective population cohort study. Maturitas 168, 71–77 (2023).

Sun, L. et al. Association between body fat and sarcopenia in older adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A cross-sectional study. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 14, 1094075 (2023).

Schwarz, P., Jørgensen, N. R., Jensen, L. T. & Vestergaard, P. Bone mineral density difference between right and left hip during ageing. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2(2), 82–86 (2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HA—Study conceptualisation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing review & editing MAK—formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing review & editing MB—writing review & editing, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study utilized routinely collected health data that was pseudoanonymized and conducted without informed consent. Ethical approval was obtained from the NRES Committee North West – Preston (Project Number: 14/NW/1136), which authorized the use of data without requiring informed consent. All procedures adhered to the principles outlined in the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

Since the data were collected retrospectively and were pseudo-anonymized for analysis, the local ethics committee (NRES Committee Northwest Preston, project number 14/NW/1136) waived the requirement for informed consent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amin, H., Khan, M.A. & Bukhari, M. Abdominal and hip fat percentages are associated with fragility fractures: evidence from a large cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 15, 23158 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07648-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07648-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Muscle mass, not fat mass, predicts vertebral fracture risk: Vietnam osteoporosis study

Osteoporosis International (2026)