Abstract

The performance of in-orbit communication satellites generally degrades over time due to depletion mechanisms, rendering them multistate systems with varying output performance levels. This paper applies grey system theory to the reliability assessment of multistate systems, specifically addressing the performance degradation and data scarcity characteristics inherent in communication satellites. A grey multi-state system model is developed to capture these dynamics. Considering the satellite’s structural characteristics, the reliability solution algorithm incorporates the potential for performance levels exceeding required thresholds. This integration is achieved by combining the grey universal generation function with the grey Markov process, using the three-parameter interval grey number as an intermediary function. Through the Lz transformation based on three-parameter interval grey numbers, the proposed dynamic reliability assessment model for multi-state communication satellites effectively mitigates challenges associated with high-dimensional state spaces in satellite systems. The developed model provides robust methodological support for reliability assessment of complex grey multistate systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The communication satellite network constitutes a critical component of the national information infrastructure, holding significant economic and social implications. As pivotal elements within these networks, communication satellites exhibit high technical complexity, lengthy development cycles, challenging maintenance requirements, and substantial investment costs, necessitating rigorous reliability assessments. During operation, satellites endure wear and tear, failure mechanisms, and diverse operational environments, where subsystem component failures may degrade satellite performance levels. Conventional reliability theory, grounded in the “two-state assumption” of binary operational states (full functionality vs. complete failure), simplifies practical problem-solving but fails to address performance degradation-induced multistate system characteristics. The multistate system reliability theory offers a novel resolution to this challenge1,2.

Since its inception, multistate system reliability theory has yielded substantial research outcomes and found extensive applications across power systems, transportation networks, aerospace engineering, and related domains2,3,4,5. Among multistate reliability assessment methodologies, Monte Carlo simulations demand extensive data support, while decision diagrams (BDD), Bayesian networks, and Petri nets encounter state-space explosion in complex systems. The Universal Generating Function (UGF) method combines discrete random variables through polynomial representations, defines system-specific operators via logical relationships, and derives system-level performance polynomials through multilayer recursion, effectively capturing multistate characteristics. Originally proposed by Ushakov6 in 1986 and subsequently refined by Gregory7, UGF has gained prominence for its computational efficiency and low complexity in multistate system reliability analysis8. However, UGF focuses on steady-state performance and probabilities, overlooking temporal dynamics and limiting applicability to discrete variables with static probability distributions. To address this, scholars developed the Lz-transform—a specialized operator integrating stochastic processes with UGF, analogous to Lz-transform for discrete variables—which ensures uniqueness in dynamic reliability analysis9,10.

Multistate reliability analysis of communication satellites via UGF requires subsystem state performance data and corresponding probabilities. However, satellite structural complexity, low component failure rates, and information scarcity hinder precise determination of subsystem state transition rates and performance levels. Grey system theory, pioneered by Deng Julong for small-sample, information-deficient scenarios11, provides an effective analytical framework. The interval grey number—a fundamental grey system element—facilitates multi-attribute uncertainty decision-making12,13. While conventional interval grey numbers assume uniform value probabilities, practical applications often involve non-uniform distributions. Furthermore, complex system operations amplify uncertainty propagation in interval grey number computations, increasing decision errors. To mitigate these limitations, Luo14,15 introduced three-parameter interval grey numbers, which have enabled advancements in sustainable transport evaluation16, grey target decision-making17, and prospect theory-based group decisions18. Despite progress, existing methods exhibit shortcomings: geometric distance-based dominance metrics in16 disregard distribution characteristics, subjective weighting persists, and distance measures in19 inadequately reflect parameter distributions. This paper contributes through:

-

(1)

Defining system performance-demand relationships via three-parameter interval grey number possibility functions, overcoming geometric distance limitations in distribution characterization.

-

(2)

Implementing computational algorithms for satellite state probabilities and dynamic reliability, resolving the state-space explosion in complex multistate systems.

-

(3)

Establishing a theoretical framework integrating three-parameter interval grey numbers with possibility functions, grey Markov processes, and Lz-transform for transient multistate satellite reliability analysis.

Preliminarie

Definitions

Definition 1

In real-world systems, beyond binary operational states (perfect functionality and complete failure), there typically exist multiple degraded states. Such systems are formally defined as multi-state systems (MSS)20,21. When system performance rates and corresponding state probabilities are represented by grey numbers, the system is termed a grey multi-state system (GMSS).

Definition 2

Let \(\left\{ {{X_n},n \in T} \right\}\) denote a stochastic process. If for any integer n and states \({i_0},{i_1}, \cdots ,{i_{n + 1}} \in I\), the conditional probability satisfies: \(P(X_{n+1}=i_{n+1}|X_{0}=i_{0}, X_{1}=i_{1},\cdots , X_{n}=i_{n})=P(X_{n+1}=i_{n+1}|X_{n}=i_{n})\), then \(\left\{ {{X_n},n \in T} \right\}\) is known as a Markov chain. For any \(n \in T\) and state \(i,j \in I\),\({P_{ij}}\left( n \right) = P\left( {\left. {{X_{n + 1}} = j} \right| {X_n} = i} \right)\) is as the transition probability of the Markov chain. If the transition probability \({P_{ij}}\left( n \right)\) s grey element ,then \(\left\{ {{X_n},n \in T} \right\}\) is called a grey Markov chain22.

Definition 3

A grey number (denoted by \(\otimes\)) represents an uncertain quantity whose exact value is unknown but bounded within a specific interval or set23.

Definition 4

An interval grey number is defined as \(a\left( \otimes \right) = \left[ {{a^l},{a^u}} \right]\) where \({a^l} \le {a^u}\) and \({a^l},{a^u} \in \mathrm{{R}}\). If \({a^l} = {a^u}\), the interval grey number reduces to a real number23.

Definition 5

A three-parameter interval grey number extends the interval grey number by incorporating a central tendency parameter: \(a\left( \otimes \right) = \left[ {{a^l},{a^ * },{a^u}} \right]\), where \({a^ * }\) denotes the center of gravity (most probable value). When \({a^ * }\) is unspecified, the three-parameter form degenerates to a standard interval grey number14.

Definition 6

Let \(a(\otimes ) = [a^l, a^*, a^u]\) and \(b(\otimes ) = [b^l, b^*, b^u]\). The arithmetic operations are defined as24:

Acronym and notation

To ensure methodological consistency, all acronyms and mathematical notations adopted in this framework are systematically documented in Table 1.

Dynamic reliability assessment model for grey multi-state communication satellites

Structure analysis

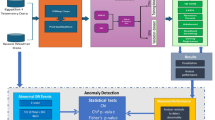

A communication satellite comprises five principal unit systems: power, communication, control, telemetry command, and antenna. The power unit system integrates solar cells and batteries in a parallel configuration. During sunlit periods, the batteries are charged, while during eclipses, they provide stable power to onboard equipment. The communication unit system consists of two key subsystems: transponders and antennas. Functioning as relay stations, transponders receive, process, and retransmit signals—essentially operating as broadband transceivers. The control unit system incorporates various electromechanical adjustment devices, including thrusters, actuators, thermal regulation units, and switching mechanisms, which maintain satellite attitude, orbital positioning, and antenna orientation under telemetry command. The telemetry command unit system collects operational parameters (voltage, current, frequency, temperature) and attitude data through sensors, transmitting them to ground stations while receiving control commands. The antenna unit system employs dedicated telemetry/command and communication antennas for directional signal transmission. Figure 1 illustrates the satellite’s structural configuration.

In operational terms, the satellite serves as a wireless relay through the coordinated operation of these unit systems. Critical components employ redundancy strategies: transponder receivers and power amplifiers typically use cold standby configurations, while telemetry processors adopt hot redundancy. As any unit system failure would result in satellite failure, reliability analysis models the satellite as a series combination of five unit systems. When considering internal subsystem redundancy within each unit system as parallel configurations, the reliability structure appears as shown in Fig. 2.

During the service life of a communication satellite system, the effects of radiation, alternating temperatures, and vacuum environments can cause random system failures in local subsystem components. These failures may occur when the system does not need to be completely taken offline and its output performance is in a derated operation mode. Let each subsystem have \({k_i} + 1\) performance levels, that is,\(0,1,2 \cdots ,{k_i}\). As can be seen from Fig.2, a communication satellite system composed of grey multi-state subsystems forms a multi-layer grey multi-state system. Let the performance levels of the power subsystem \({M_{11}}, \cdots ,{M_{1{n_1}}}\), communication subsystem \({M_{21}}, \cdots ,{M_{2{n_2}}}\), control subsystem \({M_{31}}, \cdots ,{M_{3{n_3}}}\), telemetry command subsystem \({M_{41}}, \cdots ,{M_{4{n_4}}}\) and antenna subsystem \({M_{51}}, \cdots ,{M_{5{n_5}}}\) at time t be represented by the random variables \(g_i^ \otimes \left( t \right) \in \left\{ {g_{i0}^ \otimes \left( t \right) ,g_{i1}^ \otimes \left( t \right) , \cdots ,g_{i{k_i}}^ \otimes \left( t \right) } \right\} ,i = 1,2, \cdots ,5\). The performance of the power supply system, communication system, control system, telemetry and command system, and antenna system, which are composed of the aforementioned subsystems, is denoted as \(G_j^ \otimes \left( t \right) ,j = 1,2, \cdots 5\), and the performance of the single communication satellite system is represented as \(G_s^ \otimes \left( t \right)\).

Lz-transform integration with UGF and Markov processes

For a discrete random variable G representing system performance levels with states \(G = \left\{ g_1, g_2, \cdots , g_N \right\}\) and corresponding probabilities \(P = \left\{ p_1, \cdots , p_N \right\}\),where \(p_i = \Pr \left\{ G = g_i \right\}\), the Universal Generating Function (UGF) is defined as25:

where z is a formal algebraic operator with no numerical interpretation, serving solely to pair performance levels with their probabilities.

While UGF effectively models steady-state performance, it lacks temporal resolution for transient analysis. To address this limitation, the Lz-transform was subsequently developed by integrating stochastic processes with UGF.

Let \(G\left( t \right) = \left\{ {{g_1},{g_2}, \cdots ,{g_N}} \right\}\) denote a continuous-time Markov process with:

-

State transition rate matrix \(D = \left\| {{d_{ij}}\left( t \right) } \right\|\)

-

Time-dependent state probabilities \({p_i}\left( t \right) = {P_r}\left( {G\left( t \right) = {g_i}} \right)\)

-

Initial probability distribution:

$$\begin{aligned} P_0 = \begin{bmatrix} p_1(0) = \Pr (G(0) = g_1),&p_2(0) = \Pr (G(0) = g_2),&\dots ,&p_N(0) = \Pr (G(0) = g_N) \end{bmatrix}. \end{aligned}$$(2)

The Markov process is formally expressed as:

The Lz-transform of this process is given by:

where \({p_i}\left( t \right)\) represents the transient probability of state i at time \(t \ge 0\). The operator z retains its abstract algebraic role—it does not represent a numerical variable but rather a symbolic separator between performance levels and their associated probabilities. This formalism ensures a bijective mapping between the transform and the system’s stochastic behavior under given \({P_0}\).

G-Markov model for repairable subsystems

The reliability analysis of communication satellite systems relies on subsystem performance levels and their transient probabilities. However, the structural complexity and limited test samples make precise parameter determination challenging. When performance levels and associated parameters are expressed as three-parameter interval grey numbers, the corresponding Lz transformation is termed Three-Parameter Interval Grey Number Lz Transformation (T-PIGN-Lz).

A grey multi-state repairable subsystem must satisfy the following conditions:

-

(1)

Performance Space : Subsystem i has a discrete performance space \(\left\{ {0,1, \cdots ,{k_i}} \right\}\) where states are non-negative integers..

-

(2)

Grey Performance : The performance level \(g_i^ \otimes \left( t \right)\) is a three-parameter interval grey number.

-

(3)

Grey Transition Rates : State transition rates between performance levels are three-parameter interval grey numbers.

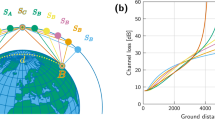

The performance level set \(g_i^ \otimes \left( t \right) = \left\{ {g_{i0}^ \otimes \left( t \right) ,g_{i1}^ \otimes \left( t \right) , \cdots ,g_{i{k_i}}^ \otimes \left( t \right) } \right\}\) s modeled through discrete Markov states, forming a G-Markov chain with grey transition probabilities, as shown in Fig.3. Here, \({k_i}\) denotes the optimal performance state while 0 represents complete failure.

Subsystem state probabilities are governed by the Kolmogorov differential equations:

Assuming the process initiates from the optimal state \({k_i}\) with performance level \(g_{i{k_i}}^ \otimes\) , the initial conditions are:

Applying Laplace-Stieltjes transformation to (5) yields:

Here, \(L\left[ \cdot \right]\) denotes the Laplace-Stieltjes operator. Inverse transformation yields time-domain probabilities:

where \(\lambda _i^ \otimes = \Big \{ \lambda _{i({k_i},{k_i}-1)}^ \otimes , \cdots ,\lambda _{i(1,0)}^ \otimes \Big \}\) and \(\mu _i^ \otimes = \left\{ {\mu _{i\left( {{k_i} - 1,{k_i}} \right) }^ \otimes , \cdots ,\mu _{i\left( {0,{k_i}} \right) }^ \otimes } \right\}\) represent degradation and repair rate vectors, respectively.

T-PIGN-Lz transform for communication satellite system

T-PIGN-Lz transform for subsystems

The T-PIGN-Lz transform aggregates the performance levels and transient probabilities of a subsystem into a grey function. For subsystem i, this transform combines9,26:

-

\(k_i + 1\) discrete performance levels \(g_{ij_i}^\otimes\) (where \(j_i = 0, 1, \dots , k_i\))

-

Corresponding time-dependent probabilities \(p_{ij_i}^\otimes (t)\)

-

A placeholder variable z (with no numerical value) to separate performance terms

where \(g_{ij_i}^\otimes\) represents the performance level \(g_{ij_i}^\otimes\), weighted by its probability \(p_{ij_i}^\otimes (t)\).

Generic combinatorial operator \(\Omega _\varphi ^\otimes\)

This operator combines the T-PIGN-Lz transforms of subsystems or unit systems according to their structural relationships (e.g., series, parallel). The operator applies a structure function \(\varphi\) to map subsystem performances to the system-level performance.

For a unit system j composed of n subsystems:

Expanded form:

Structure functions

-

Series Systems (\(\varphi _s\)): The system performance equals the minimum subsystem performance27,28:

$$\begin{aligned} \varphi _s\left( g_1^\otimes , \dots , g_n^\otimes \right) = \min \left( g_1^\otimes , \dots , g_n^\otimes \right) . \end{aligned}$$(12) -

Parallel Systems (\(\varphi _p\)): The system performance equals the sum of subsystem performances27,28:

$$\begin{aligned} \varphi _p\left( g_1^\otimes , \dots , g_n^\otimes \right) = \sum _{i=1}^n g_i^\otimes . \end{aligned}$$(13)

System-level T-PIGN-Lz transform

For a communication satellite system composed of N unit systems:

Expanded form:

where \(K_j\) is the number of states for unit system j.

State space mapping

The system’s performance levels arise from the Cartesian product of unit system states25:

where \(K_s = \prod _{j=1}^N K_j\) represents the total system states.

Dynamic reliability calculation

The system reliability \(D(W_\otimes , t)\) computes the probability that the system meets mission requirements \(W_\otimes\)29,30:

The term \(p\left( G_s^\otimes \ge W_\otimes \right)\) is evaluated using the possibility function f(x):

Usually, the possibility of taking the value of \(a(\otimes )=\left[ a^{l},a^{*},a^{u} \right]\) decreases from the center of gravity point \(a^{*}\) to the upper bound \(a^{u}\) and the lower bound \(a^{l}\). From Fig.4 it can be seen that when the system performance demand is \({W_{1 \otimes }}\), the system is unreliable, that is \(p\left( {G_s^ \otimes \ge {W_{1 \otimes }}} \right) = 0\); when the system performance demand is \({W_{2 \otimes }}\), the system is reliable, that is \(p\left( {G_s^ \otimes \ge {W_{2 \otimes }}} \right) = 1\); when the user demand is \({W_{3 \otimes }}\) or \({W_{4 \otimes }}\), there is uncertainty as to whether the system is reliable or not, that is \(0< p\left( {G_s^ \otimes \ge {W_{3\left( 4 \right) \otimes }}} \right) < 1\). Therefore, it is necessary to analyze which performance state satisfies the task demand.

Let \(r_s^ \otimes = g_s^ \otimes - {W_ \otimes }\), \(p\left( {G_s^ \otimes \ge {W_ \otimes }} \right)\) denote the probability that \(G_s^ \otimes \ge {W_ \otimes }\) and \(f\left( {r_{_s}^ \otimes } \right)\) be the possibility function for \({r_s}\). The probability of \(G_s^ \otimes \ge {W_ \otimes }\) is defined as

An illustrative example

Consider a multi-state communication satellite system comprising five unit systems and six performance degradation subsystems, whose structure is illustrated in Fig. 5. Unit system 1 contains the power system (subsystem 1). Unit system 2 incorporates two homogeneous and isomorphic communication systems (subsystems 2 and 3). Unit system 3 encompasses the control system (subsystem 4). Unit system 4 includes the telemetry command system (subsystem 5), while unit system 5 comprises the antenna system (subsystem 6). The communication system primarily facilitates control command transmission, establishes space-ground links, and ensures reliable inter-satellite connectivity, which critically determines the operational success of the satellite communication system. Redundancy strategies such as cold standby configurations for receivers and high-power amplifiers in satellite transponders are implemented to maintain operational stability. Parallel structures represent the component redundancy. Each subsystem’s performance levels and state transition rates are defined as three-parameter interval grey numbers, as detailed in Table 2. Subsystem 2 exhibits identical state transition rates and performance characteristics to Subsystem 3. Given the mission-required performance threshold of the communication satellite system \({W_ \otimes } = \left( {0.4,0.5,0.6} \right)\), evaluate the system reliability at \(t=1\) year.

Solving for dynamic reliability of communication satellites

G-Markov state probability solution for each subsystem

The probabilities of subsystems 1 to 6 operating at each performance level can be derived from the established G-Markov model, as presented in Table 3.

T-PIGN-Lz transformation functions for subsystems

The T-PIGN-Lz transformation for each subsystem at t=1 can be directly derived from the performance levels in Table 2 and their corresponding probability distributions in Table 3 using Equation (20).

T-PIGN-Lz transformation functions for unit systems

As shown in Fig.5, the performance level of subsystem 1 corresponds directly to unit system 1, expressed as \(G_1^ \otimes = g_1^ \otimes\). Similarly, the relationships hold: \(G_3^ \otimes = g_4^ \otimes ,G_4^ \otimes = g_5^ \otimes ,G_5^ \otimes = g_6^ \otimes\).

Unit system 2 contains two parallel subsystems with identical performance characteristics, where \(G_2^ \otimes = {\varphi _p}\left( {g_2^ \otimes ,g_3^ \otimes } \right)\):

Reliability analysis of communication satellite systems

The integrated communication satellite system consists of five serially connected unit systems, expressed as:

The system exhibits \(K_{s}\)=3\(\times\)10\(\times\)4\(\times\)3\(\times\)3=1080 distinct performance levels, with its T-PIGN-Lz transformation formulated as:

System reliability at \(t=1\) year given mission requirement \({W_ \otimes } = \left( {0.4,0.5,0.6} \right)\) is computed through comparative analysis of performance levels:

Communications satellite system reliability analysis

Sensitivity analysis

Communication satellite systems require varying performance levels for different missions, necessitating reliability analysis under diverse performance requirements. As the system’s mission demands performance ranges from 0 to 0.9, the reliability of the communication satellite system decreases with increasing demand. Fig.6 demonstrates that when the mission demand performance is 0, the reliability of the system asymptotically approaches 1 at t = 1. For mission demand performance between 0.1 and 0.4, the impact on system reliability is minimal. However, when the demand increases to 0.5–0.9, the reliability declines sharply, eventually approaching zero. This indicates an inverse relationship between task demand performance and system reliability.

To analyze the combined effects of time and performance requirements on system reliability, a three-dimensional bar chart (Fig.7) illustrates the most probable reliability values across time (1–10 years) and task demand performance (0–0.9). Fig.7 reveals that system reliability decreases with higher demand, particularly when \({W_ \otimes } > 0.4\). Over time, reliability diminishes for fixed demand levels, with larger demands exacerbating this trend. At low task demand performance, reliability primarily depends on time; as demand increases, task performance requirements dominate reliability variations.

Weakness analysis

The reliability-based vulnerability assessment evaluates the impact of individual unit system failures on overall system reliability. The critical vulnerability is identified as the component demonstrating the most substantial influence. Initial system reliability is calculated under nominal operating conditions. Subsequent fault simulations employ exhaustive traversal methodology, systematically evaluating each unit failure scenario (excluding T-PIGN-Lz transformations for failed units). Significant deviation from baseline reliability identifies vulnerable components. Fig. 8 demonstrates comparative reliability metrics for failures in Unit Systems 1–5, with nominal operation as reference. The analysis reveals Unit System 1 as the primary reliability bottleneck, followed by Unit System 2.

Further, Parametric sensitivity analysis examines \(\lambda _{1\left( {2,0} \right) }^ \otimes\) and \(\lambda _{1\left( {2,1} \right) }^ \otimes\) effects on system reliability within Unit System 1. Figures 9 and 10 quantify reliability variations when scaling these parameters under constant mission requirements. The results demonstrate greater sensitivity to \(\lambda _{1\left( {2,1} \right) }^ \otimes\) perturbations, identifying it as the critical vulnerability. Mitigation strategies include either enhancing \(\mu _{1\left( {1,2} \right) }^ \otimes\) or reducing \(\lambda _{1\left( {2,1} \right) }^ \otimes\).

Comparative analysis

Under the mission requirement \({W_ \otimes } = \left( {0.4,0.5,0.6} \right)\), Fig. 11 compares the reliability predictions between the proposed method and the traditional reliability assessment method. The results show high consistency between the two approaches, which empirically validates the accuracy of the proposed model to a certain extent. However, it is worth noting that traditional reliability assessment methods have limitations when evaluating systems with a large number of states. For instance, in the case study presented in this paper, the total number of system states reaches 1,080. Traditional methods struggle to effectively handle reliability evaluation at such a large scale of states, whereas the proposed method demonstrates the capability to rapidly assess reliability for systems with extensive state configurations (as exemplified by the 1,080-state system in this study). This highlights the significant advantage of the proposed method over traditional approaches in handling reliability assessment for complex systems.

As shown in Fig. 12, when the system state performance takes the most probable value, the proposed method exhibits strong agreement with the Monte Carlo simulation results, validating the mathematical rigor of our approach. Notably, by introducing a confidence interval prediction mechanism, the proposed method fully encapsulates all Monte Carlo simulation results within its prediction bounds, demonstrating superior capability in uncertainty quantification. In terms of computational efficiency, the Monte Carlo simulation requires 8,520 seconds to complete due to exhaustive state-space sampling, while the proposed method achieves equivalent accuracy in only 50 seconds through state-space dimensionality reduction—a 170× speedup. This highlights the synergistic optimization of accuracy and efficiency in the proposed method, making it particularly suitable for real-time reliability assessment of large-scale multi-state systems.

Conclusion

This paper applies the three-parameter interval grey number to characterize the performance of grey multi-state systems, establishing a novel framework for reliability assessment of communication satellites through the integration of Lz-transformation and grey Markov processes. Our methodology defines the performance-demand relationship using possibility functions of three-parameter interval grey numbers, effectively addressing interval expansion challenges in reliability computation. The proposed approach reduces computational complexity in determining state probabilities through algorithmic optimization and computer-assisted solutions, while demonstrating superior performance in handling transient states compared to traditional methods. Future research should focus on: (1) extending the framework to multi-satellite constellation reliability modeling with inter-satellite dependencies; (2) developing hybrid models combining T-PIGN-Lz with Bayesian networks for complex failure propagation analysis; and (3) investigating time-varying mission requirement patterns and their reliability implications.

Data availability

The data (source code) supporting this study’s findings are available in the supplementary material of this article. The latest source code is available at https://github.com/shaorr311/reliability-assessment.

References

Qin, J. & Coolen, F. P. A. Survival signature for reliability evaluation of a multi-state system with multi-state components. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf.218 (2022).

Jia, H. et al. Reliability evaluation of power systems with multi-state warm standby and multi-state performance sharing mechanism. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf.204 (2020).

Chakraborty, S., Goyal, N. K., Mahapatra, S. & Soh, S. A monte-carlo markov chain approach for coverage-area reliability of mobile wireless sensor networks with multistate nodes. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf.193 (2020).

Lin, Y.-K., Nguyen, T.-P. & Yeng, L.C.-L. Reliability evaluation of a multi-state air transportation network meeting multiple travel demands. Ann. Oper. Res. 277, 63–82 (2019).

Lyu, H., Qu, H., Xie, H., Zhang, Y. & Pecht, M. Reliability analysis of the multi-state system with nonlinear degradation model under markov environment. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf.238 (2023).

Ushakov, I. A universal generating function. Soviet J. Comput. Syst. Sci. 24, 118–129 (1986).

Gregory, L. Multi-state System Reliability, 207–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/b100619 (World Scientific, 2011).

Xia, W. et al. Reliability analysis for complex electromechanical multi-state systems utilizing universal generating function techniques. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf.244 (2024).

Hu, L., Su, P., Peng, R. & Zhang, Z. Fuzzy availability assessment for discrete time multi-state system under minor failures and repairs by using fuzzy lz-transform. Mainten. Reliab. 19, 179–190 (2017).

D’Amico, G., Masala, G., Petroni, F. & Sobolewski, R. A. Managing wind power generation via indexed semi-markov model and copula. Energies 13, 4246 (2020).

Hu, M. & Liu, W. Grey system theory in sustainable development research-a literature review (2011–2021). Grey Syst. Theory Appl. 12, 785–803 (2022).

Xie, N. Interval grey number based project scheduling model and algorithm. Grey Syst. Theory Appl. 8, 100–109 (2018).

Li, P. & Wei, C. A new two-stage grey evaluation decision-making method for interval grey numbers. Kybernetes 47, 801–815 (2018).

Luo, D. & Wang, X. The multi-attribute grey target decision method for attribute value within three-parameter interval grey number. Appl. Math. Model. 36, 1957–1963 (2012).

Luo, D. Decision-making methods with three-parameter interval grey number. Syst. Eng. Theory Pract. 29, 124–130 (2009).

Bai, C., Fahimnia, B. & Sarkis, J. Sustainable transport fleet appraisal using a hybrid multi-objective decision making approach. Ann. Oper. Res. 250, 309–340 (2017).

Dong, F., Wu, L., Liu, H., Shen, H. & Zhai, Z. Multi-attribute decision analysis on three-parameter interval grey number based on bellshaped possibility. J. Grey Syst. 34, 59–74 (2022).

Yan, S., Liu, S. & Wu, L. A group grey target decision making method with three parameter interval grey number based on prospect theory. Control Decis. 30, 105–109 (2015).

Li, Y., Zhang, D. & Liu, B. Multi-attribute decision-making method based on cosine similarity with three-parameter interval grey number. J. Grey Syst. 31, 45–58 (2019).

Li, Y., Chen, Y., Zhang, Q. & Kang, R. Belief reliability analysis of multi-state deteriorating systems under epistemic uncertainty. Inf. Sci. 604, 249–266 (2022).

Akrouche, J., Sallak, M., Chatelet, E., Abdallah, F. & Chehade, H. H. Methodology for the assessment of imprecise multi-state system availability. Mathematics10 (2022).

Liu, S., Yang, Y. & Forrest, J. Grey Data Analysis (Springer, 2017).

Ye, J. & Dang, Y. A novel grey fixed weight cluster model based on interval grey numbers. Grey Syst. Theory Appl. 7, 156–167 (2017).

Meng, F., Wang, N. & Li, B. Selection method of evaluation indicators with three-parameter interval grey number. Open J. Appl. Sci. 05, 833–840 (2015).

Babaei, M., Rashidi-baqhi, A. & Rashidi, M. Estimating project cost under uncertainty using universal generating function method. J. Constr. Eng. Manag.148 (2022).

Azhdari, A. & Ardakan, M. A. Reliability optimization of multi-state networks in a star configuration with bi-level performance sharing mechanism and transmission losses. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf.226 (2022).

Dong, W. et al. Reliability assessment for uncertain multi-state systems: An extension of fuzzy universal generating function. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 21, 945–953 (2019).

Levitin, G. Universal Generating Function and Its Application (Springer, 2005).

Zio, E., Marella, M. & Podofillini, L. A monte carlo simulation approach to the availability assessment of multi-state systems with operational dependencies. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 92, 871–882 (2007).

Frenkel, I. & Ding, Y. Multi-state System Reliability Analysis and Optimization for Engineers and Industrial Managers (Springer, 2010).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Youth Program for Humanities and Social Sciences Research of the Ministry of Education of China under Grant No. 23YJCZH180, titled “Expediting the Development of China’s Communication Satellite System: Dynamic Efficiency Measurement and Strategic Breakthrough Selection.” It also received support from the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions in China under Grant No. 23KJD120003, titled “Investigation into Multi-task Efficiency Evaluation and Optimization Model of Agent-GERT Network for Dual-layer Maritime Satellite Communication Systems.” Additionally, this study aligns with the Key Project of the Jiangsu Provincial Education Science Planning under Grant No. B-b/2024/01/42, titled “Strategic Design and Practical Exploration for High-quality Development of Jiangsu Provincial Universities: Bottleneck Breakthroughs, Comprehensive Evaluation, and Paradigm Construction.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shao, R., You, W. & Nie, Y. Reliability modeling framework of satellite constellation based on three-parameter interval grey number Lz transformation. Sci Rep 15, 21022 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07789-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07789-7