Abstract

This paper outlines the findings of an investigation on alkali activated fly ash mixtures to provide a comprehensive view of the effects of reactive oxide ratios on flowability, setting, compressive strength, early kinetics, and reaction products. Alkali-activated fly ash mixtures prepared based on reactive potential provide consistent strength under room-temperature conditions using low molarity sodium hydroxide. Under room-temperature curing, the low calcium dosage provided by 5% substitution of fly ash by slag leads to higher strength. The inclusion of slag enhances the early reactivity contributing to setting control. The early reactivity is enhanced with slag inclusion at a small proportion in the binder and the higher early kinetic activity contributes to larger fly ash dissolution. There is a synergistic enhancement of strength due to the enhanced formation of sodium alumino-silicate hydrate (NASH) geopolymers with the inclusion of slag. A systematic procedure for producing high compressive strength fly ash binders from the activation process of a given fly ash at room temperature curing is presented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The cement industry has been rapidly expanding to meet growing concrete demands for infrastructure projects, with around 4 billion tonnes of cement produced annually, up from 3.27 billion tonnes in 2010, and it is expected to reach 4.83 billion tonnes by 20301. This increase, however, has significant environmental impacts because the cement manufacturing process produces large amounts of CO2, which is one of the main greenhouse gases2. According to the IPCC’s report3, the 1.5 °C global warming level will be exceeded earlier than expected, and it may even exceed that to reach 2 °C in the coming decades. As a result, the global focus has moved to adopting sustainable solutions, with the development of alternative types of cement and the use of industrial by-products becoming increasingly important. Geopolymers produced from the alkali-activation of fly ash are currently considered as sustainable replacements to Portland cement due to their exceptional mechanical characteristics, fire resistance, and durability4.

By-product materials rich in alumina (Al2O3) and silica (SiO2), such as fly ash, metakaolin, and blast furnace slag, are the preferred aluminosilicate source materials for producing alkali-activated binders5. These materials are activated by an alkali activator that in most cases consists of sodium silicate (SS) and sodium hydroxide (SH) solutions6. The activation process mainly involves two stages, dissolution of reactive aluminates and silicates from the source material and the polycondensation of the dissolved aluminates and silicates to form cross-linked aluminium silicate binder network7. Low calcium (Class F or siliceous) fly ash, which is produced during the coal combustion process in coal-fired power stations, is one of the most used materials in the manufacture of geopolymer binders. It accounts for approximately 70% of total coal combustion residues8. The chemical and physical characteristics of fly ash vary based on the type of coal and the thermal power plant used9. Fly ash with a high content of amorphous aluminosilicates (mainly silica and alumina, along with smaller amounts of calcium oxide, iron oxide, and magnesium oxide) and fine particles exhibit higher reactivity, increasing the degree of geopolymerisation and thus improving mechanical properties10.

There is no standard method for producing geopolymers11. However, several parameters that influence the geopolymerisation process have been identified, including fly ash composition (percentage of reactive silica (SiO2) and alumina (Al2O3) in the fly ash); activating solution composition (molarity of NaOH, the ratio of SS/SH and the dissolved silica content in the alkaline activator); the water to solids ratio in the paste; and curing conditions12. There are currently three main approaches to improve the compressive strength and accelerate the reaction rate in low calcium fly ash binders13. The first approach is to use elevated temperatures in the range of 60 °C to 90 °C for 6 to 24 h to enhance cross-linking and polymerisation7,14,15,16,17. Elevated temperatures enhance the reactivity of fly ash, increasing the dissolution of reactive species from the fly ash and accelerating the formation of sodium aluminosilicate hydrate (NASH) gel18. Heat cured geopolymer binders reach more than 90% of their maximum strength within the first 24 h of curing when compared to ambient cured geopolymer binders17. The second approach to achieve high strengths is by increasing the alkali activator’s concentration. Fly ash-based geopolymers prepared with alkaline activators with very high basicity given by NaOH of 14 M can obtain high strengths irrespective of curing temperature or age20. Microstructure analysis revealed that fly ash solubility increases with [OH-], leading to rapid formation of geopolymer gel21. The third approach to increasing the final strength of fly ash binders is to use reactive additives and replacements such as slag in the activated system. Binders containing slag as fly ash replacement were found to improve early-age strength development and final strength17,23,24,25. However, in order to achieve high compressive strengths, higher percentages of slag replacements, close to 50% or more, are required26. Reddy and Subramaniam27 reported that the addition of slag at 20% replacement of fly ash or higher produces calcium-based reaction products. The strength gain results from the formation of calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (CASH) gel, that is similar in properties to cement hydration product. The presence of Ca2+ supplied by slag at 20% proportion of the binder and higher impedes the formation of sodium based geopolymers. While increasing the slag ratio improves strength, it reduces workability28.

The approaches for achieving higher mechanical properties come at the cost of other important factors. For example, the use of heat curing limits the onsite use of geopolymer, restricting it to precast applications. Using higher concentrations of NaOH is considered a safety issue and adds to the cost. Furthermore, using slag as a replacement is not considered a cost-effective option and it is known to reduce the fresh properties as well as increase the shrinkage29. Despite the fact that geopolymers provide numerous environmental benefits, their use and applications are specifically limited. Most researchers concur that the key barriers to industrial acceptance are poor fresh properties, complex mixing and curing processes, and the high production cost. Developing a cost-effective ambient-cured fly ash binder with high compressive strength and good fresh properties still requires additional research and attention. This research explores the possibility of producing relatively high compressive strength fly ash binders without the use of high molarity activators, heat curing, or high percentages of cementitious additives while maintaining good fresh properties.

Materials and methodology

Characterisation of materials

A formulation for room temperature cured fly ash-based binder paste is developed using reagent grade activators. A consistent basis for achieving high strength from activated fly ash with the minimum use of NaOH is developed in terms of the reactive content of fly ash. Room temperature curing is achieved with slag addition at low dosage. The formulation is then repeated with fly ash from a different source and using industrial grade activators. Identical results are achieved in terms of strength using the formulation of the activated mix based on reactive components in fly ash.

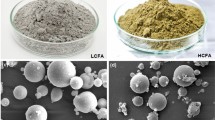

Fly Ash and blast furnace slag

Two different types of low calcium fly ash were used in the study. The first fly ash labelled (R) and was supplied by Cement Australia Pty Ltd. from Gladstone power station. In addition, a fly ash labelled (N) was collected from the Ramagundam combustion power plant, in Telangana State of India. The basic mixture formulation was developed using type N fly ash. Both types of the fly ash meet the conditions of the IS 3812 Indian Code of practice fly ash that is siliceous30 and of fly ash defined as “Class F” according to ASTM C 61831. The chemical compositions of both fly ash are listed in Table 1. Crystalline and amorphous phase contents of the fly ash are indicated in Table 2. The fly ash used in this research have comparatively high SiO2 and Al2O3 contents and small calcium contents. Locally sourced blast furnace slag obtained from Building Products Supplies Pty Ltd. was used as an additive, with its chemical composition listed in Table 132.

Alkaline activator

The alkali activator was made with analytical grade sodium hydroxide (NaOH) in solid form (97–98% purity) and liquid sodium silicate (Na2SiO3). Two grades of sodium silicate solutions were employed: analytical grade (labelled as G) and industrial grade (labelled as V). Table 3 illustrates the chemical characteristics of the two sodium silicate solutions as provided by the suppliers.

Mix design

The mixture proportions of the activated mixtures are identified in Table 4. All activated mixtures were prepared with the mass proportion of binder to activating solution equal to 1.0: 0.35. The binder in the activated system is identified with fly ash and slag (when used). The proportioning of the mixtures was based on the reactive content in the activated paste. Reactive SiO2 content of an activated paste is the reactive SiO2 present in the fly ash and the SiO2 provided by the sodium silicate. The reactive Al2O3 in the activated paste is the reactive Al2O3 found in the fly ash. Previous research has established that consistently high strength geopolymers are achieved from activated fly ash when the proportion of the (reactive silica)/(reactive alumina) is close to 2.0, and the proportion of (reactive silica)/Na2O > 5.0 in the activated fly ash paste33. A small variation was introduced to evaluate the sensitivity of the system to variation in the external silica supplied in the activating solution. The activating solution content and the water content in the binder were kept constant to eliminate the influences of these variables on the outcomes. Further the [OH−] concentration was kept within a small range close to 3.0 M NaOH. A minimum concentration of 3 M NaOH in the alkaline activator ensures complete dissolution of the fly ash glassy phase12. Alkaline activators were made by mixing the ‘as-received’ sodium silicate solution with an 8 M solution of NaOH solution in different mass proportions ranging from 2.0 to 3.0. The final masses of the individual components of the activating solution are listed in the Table 4.

Activated mixtures with 5% mass of fly ash replaced by slag were also prepared. The [OH−] concentration and the water content (mass of water in proportion to solids) were fixed. The requirement of sodium silicate, NaOH and water in the activating solution varied slightly depending upon the sodium silicate solution used.

The general notation of a paste mixture was as follows: XAYS-L-C-Z, where X denotes the mass proportion of fly ash in the mix. The A represents the type of fly ash used, which can be type N or R. The Y represents the mass proportion of slag in the mix, and S refers to slag. The L represents the alkaline activator to binder materials mass ratio (combined mass of fly ash and slag). The C is the mass proportion of the as received sodium silicate to 8 M NaOH solution (SS/SH ratio). The Z refers to the type of Na2SiO3 solution used in the mix (G or V). In the test matrix, geopolymer paste mixtures were initially produced by activating fly ash with an alkaline activator.

Preparation details

Initially, an 8 M solution of NaOH was prepared just prior to mixing the paste. The quantities of water and NaOH solids needed to prepare the required NaOH molarity were calculated based on the approach presented by Hardjito and Rangan34. When the temperature of the 8 M NaOH solution was 45 °C, it was mixed with the Na2SiO3 solution. The geopolymer pastes were mixed using a paddle mixer. After dry mixing the binder materials (fly ash and slag) for 3 min, the alkaline activator was added to the dry ingredients and mixed for 7 min to achieve a homogeneous mix.

Compressive strength

For compression testing, steel moulds were used to cast 50 mm cubes. The mixes were cast in two layers, each of which was vibrated. After casting, the specimens were then wrapped with plastic to maintain a constant moisture content and stored at room temperature (25 ± 1 °C). The specimens were demolded after 24 h, placed in resealable plastic bags, and cured further at 25 ± 1 °C until testing day (3, 7, 14, and 28).

Setting time measurements

According to ASTM C191-0836, the setting times of fly ash pastes were measured using a Vicat apparatus. The initial setting time is the time when a Vicat needle with a dimeter of 1 ± 0.05 mm penetrates 25 mm into the paste.

where E is the time in minutes of last penetration (> 25 mm), H is the first penetration time in minutes (< 25 mm), C is the penetration reading at time E, and D is the penetration reading at time H. The final setting time is the time when the Vicat needle leaves a negligible mark on the paste’s surface.

Isothermal calorimetry measurement

An isothermal calorimeter with an in-situ mixing facility was used for heat flow measurements27. Calorimetric measurements were performed with in-situ mixing of the activated paste inside the calorimeter. The binder material was placed inside the calorimeter and allowed to equilibrate. The activating solution was injected with a syringe and mixing was performed inside the calorimeter with a stirrer motor set to 100 rpm for 5 min. For heat flow measurements, natural, high purity sand was used as the reference.

XRD measurement

XRD measurements were carried out following procedures developed previously12,27. The scans were performed in a Bragg-Brentano θ-θ goniometer that is vertical at 2θ angles that range from 20 to 70 degrees. A Cu-Kα radiation source was employed. Soller slits that are of two types were utilised for both the diffracted beams and the incident, one with (2.5- and 0.6-mm width) and the other with (4- and 8-mm width). To reduce air scattering, a 2 mm air scatter screen unit was placed above the specimen. With a step size of 0.02 degrees, the measurements were taken at a rate of 0.6 steps per second. During the acquisition, the specimens were rotated at 15 rpm.

The Rietveld refinement technique was used to refine the crystalline phases found in the material12,27,37,38. In order to establish the intensity signature of overall amorphous material, the Pawley refining technique was applied22. The direct decomposition approach, which was used to compute the quantities of individual amorphous phases within the overall amorphous content. The direct decomposition method was first developed by Bhagath Singh and Subramaniam22 to quantify the amorphous phase present in fly ash binders. This method decomposes the intensity signature of the total amorphous phase in the activated material into the intensity signatures of the amorphous unreacted fly ash phase and reaction products. The mass percentage of a phase present within the entire material, wphase, is expressed as

where Iphase and Itotal are the areas under the phase and total material intensity profiles, respectively.

Test results and analysis

Fly Ash mixes

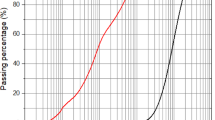

The flow measurements from activated paste mixtures with different proportions of SS to SH are shown in Fig. 1a. The changes from the flow measurements, however, do not indicate the physical state of the paste. The alkaline activating solution was very viscous, and its viscosity increased with SS/SH ratio from 2.0 to 3.0. The viscosity of an alkaline activating solution is known to increase with its silica content or SS/SH ratio39. Pastes made with activated solutions containing a higher SS/SH ratio became increasingly sticky and difficult to mix. The flow measurements are not sensitive to the change in the physical state of the mixture that relate to difficulty in mixing and stickiness. Even the very sticky mixes exhibited a continued flow with time and reached similar diameters. Alkali-activated fly ash paste is known to exhibit a Maxwell flow behaviour, which continues to produce deformation, which is associated with viscoelastic deformation even in very stiff mixes45.

The change in the SS/SH ratio in the alkaline activating solution had no influence on the setting times of the activated paste mixtures, as shown in Fig. 1b. The effect of SS/SH ratio in the activating solution on 7- and 28-day compressive strengths is presented in Fig. 1c. Increasing the dissolved silica content in the activating solution enhanced the 28-day strength. The 7-day strengths, on the other hand, showed a slight decrease, indicative of the initial retardation of silica in the activating solution.

Fly Ash and slag mixes

The inclusion of slag in the binder influenced the flow of fly ash paste, as depicted in Fig. 2a. Generally, the flow value reduced with the addition of slag in the mixture. The flowability of 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G, which contains 5% slag, was very comparable to the control mixture with an 8.5% reduction. The strength gain of the mixture comprising only fly ash as the binder material was slower. The presence of slag in the binder improved the rate of strength gain. When slag was added to the binder, the strength increased significantly as early as 3 days. At 28 days, paste mixtures containing 5% slag in the binder had a 16% higher strength than the reference mixture (no slag) as demonstrated in Fig. 2c. Therefore, 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G mixture produced desirable fresh and hardened properties, with a compressive strength of 61.2 MPa, flowability of 130%, and initial and final setting times of 8.5 h and approximately 14 h, respectively as shown in Fig. 2b.

Kinetics from calorimetry

The heat flow measured from the 100N0S-0.35-2.5-G and the 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G is shown in Fig. 3. The measured heat flow in the first 3 h is displayed in the inset for clarity. There is clearly only one peak visible in the measured heat flow. The prominent peak appeared within 30 min of adding alkaline activator to the binder materials. The first peak is produced by the wetting and initial dissolution of fly ash and slag in the alkaline solution27. The dissolution peak is typically of a very short duration. The intensity and the duration of the first peak measured from the two paste samples indicated early reactivity associated with slag hydration and precipitation. There was clearly a larger peak in paste with 5% slag in the binder indicating a more significant early activity. The heat flow indicated a continued decrease in the activity following the initial dissolution peak. The total heat increased steadily for both mixtures. A clear difference in the total heat measured from the two activated mixtures was produced within the first 24 h. At 24 h, the total heat measured from the mixture without slag increased to 15.1 (J/g), while it was 17.4 (J/g) for the mixture with slag. The higher early reactivity provided by slag therefore contributed to a significant difference in the extent of reaction in the mixture with slag within the first 24 h. There was a continued linear increase in the heat after 24 h. The difference in the cumulative heat recorded from the two samples essential remained constant after 24 h. The calorimetric measurements clearly indicated that 5% slag in the binder produces an increase in the early reactivity within the first 24 h. The continued reaction within the binder was essentially similar in binder with and without slag.

XRD analysis

Typical XRD intensity signatures from mixtures 100N0S-0.35-2.5-G and 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G at 3 and 28 days of age are presented in Fig. 4, respectively. The prominent crystalline peaks produced by Quartz and Mullite are clearly identified in the XRD intensity signatures of the hardened paste. The crystalline peaks remained largely unaltered between 3 and 28 days. There was also a large hump in the intensity signature, which was prominently characterised between 2q angles ranging from 15 to 35 degrees. The broad hump in the intensity pattern was produced by scattering from the amorphous phase within the activated mixture. A combination of the glassy phase in the fly ash and amorphous reaction products formed within the alkali-activated mixture make up the total amorphous phase. The amorphous hump changed between 3 and 28 days. The amorphous hump appeared to be centred around 25° 2q at 3 days. At 28 days there appeared to be a shift in the hump to a higher 2q angle, with the centre close to 30°.

Quantitative analysis of the XRD intensity signature was performed to extract the intensity signatures of the different crystalline phase and the amorphous hump present in the alkali activated mixture. The intensity signatures of the individual crystalline phases and the total amorphous content in the 28-day sample of 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G are shown in Fig. 5. The Rietveld refinement procedure was used to obtain the signatures of intensity of the individual crystalline phases and are shown in the figure. The intensity signature of the total amorphous phase in the alkali activated fly ash was obtained using the Pawley refinement procedure43. An hkl phase was defined for a cubic structure with \(\:Fm\overline{3}m\) space group (space group No. 225)22. The crystalline phases present in the fly ash were all identified in the decomposed intensity signatures. Additional crystalline phases were present in negligible quantities. The presence of two peaks is also clearly identified in the intensity signature of the amorphous phase extracted from the total intensity signature.

Figure 6 shows the intensity patterns associated with the diffuse scattering produced by the amorphous phase in the activated paste at different ages. The presence of two distinct peaks was clearly identified in the amorphous hump. There was clearly a change in the shape of the intensity pattern of the total amorphous phase present in the activated samples with age. Initially, at 3 days the hump centered on 20° 2q was more prominent, while at 28 days the hump with a peak centered at 30° 2q was more prominent. The hump centered at 20° is produced by the fly ash glassy phase, whereas the hump centered on 30° is produced by the NASH gel formed within the alkali-activated paste. The progressive shift in the intensity pattern with age indicated a continued dissolution of the glassy phase in the fly ash and increasing formation of NASH gel.

The broad intensity signature of the total amorphous phase in the alkali activated fly ash was decomposed into underlying intensity profiles of unreacted glassy phase in fly ash and NASH following the direct decomposition procedure19,22. Unconstrained non-linear optimization was used to fit pseudo-Voigt (PV) peaks to the intensity signature of the total amorphous phase. The decomposition of the total intensity signature in the alkali-activated material into the signatures of unreacted glassy phase in fly ash and NASH gel is illustrated for 28-day samples of 100N0S-0.35-2.5-G and 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G in Fig. 7. The individual intensity signatures of the fly ash glassy phase and NASH were identified in the decomposed intensity signature of the total amorphous hump. The intensity signature of NASH is identified with PV peaks centred on 29.5°.

The unreacted fly ash glassy phase and NASH contents in the activated pastes obtained through direct decomposition technique are shown in Fig. 8. The glassy content in both activated pastes decreased steadily with age. There were small differences of fly ash unreacted glassy content that were seen by 3 days. The small differences were also contributed by the smaller fly ash content in 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G when compared to 100N0S-0.35-2.5-G. There was a more rapid dissolution of the glassy phase in fly ash in the first 14 days in 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G when compared to 100N0S-0.35-2.5-G. This indicates a higher reactivity of fly ash in the mixture containing 5% slag. Correspondingly, there was a significantly more rapid formation of NASH in the first 14 days in 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G when compared to 100N0S-0.35-2.5-G. The NASH content at 28 days in 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G was also higher when compared to 100N0S-0.35-2.5-G. The presence of slag appears to enhance the dissolution of the fly ash glassy phase and the NASH content. The early dissolution of slag contributed reactive species, which promoted the formation of NASH at a more rapid rate. The NASH formation and the depletion of reactive species promoted the faster dissolution of fly ash.

Validation of the mix design

To assess the robustness of the developed mix design, mixtures prepared with different fly ash and sodium silicate sources were used for internal validation of the results. This is necessary because the physical properties and chemical compositions of fly ash depend on the type of coal used, as well as the combustion and cooling processes used in coal-fired power plants. Moreover, the sodium silicate solutions are available in different forms, grades, and concentrations. For these reasons, a consistent basis for producing stable high compressive geopolymer binders that can be applied to various types of fly ash and alkaline activators was developed from the experimental program findings. The oxide ratios of the optimal mixture were determined and analysed as shown in Table 5 to be used as a guideline for producing binders with high strength and adequate fresh properties from low calcium fly ash, which was cured at room temperatures. The oxide ratios in the activated paste and the final molarity of the alkaline activator were the main factors considered in the production of high strength fly ash binders. From Table 4, the outcomes are aligned with the findings of a previous research performed by Singh and Subramaniam22. While the oxide ratio of reactive silica to alumina in the activated paste was close to 2.0 and the ratio of reactive silica to Na2O was greater than 5.0, a higher strength was obtained with increasing SiO2 content in the alkaline activator. The activated system’s oxide ratios were calculated using the reactive SiO2 and Na2O found in both the source material and the alkali activator. A compromise between workability and strength was obtained when the silica content, or the mass proportion of SiO2 to H2O in the alkaline solution was close to 73.5 to 213.5 (close to 0.33).

A validation of the findings from the experimental study was performed using a different fly ash and sodium silicate solutions. The mixture 95R5S-0.35-2.5-G was produced with fly ash R which was supplied from a different supplier and had a different composition in terms of reactive silica and alumina. Fly ash R contained 23.0% reactive silica and 15.2% reactive alumina, compared to 26.4% and 16.3% in fly ash N. The activated paste was prepared by keeping the final reactive SiO2/Na2O greater than 5.0 and reactive SiO2/reactive Al2O3 ratio close to 2.0. The SiO2/H2O proportion and the concentration of NaOH in the alkaline solution were both similar to 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G. The 28-day compressive strength achieved from 95R5S-0.35-2.5-G was 62 MPa. Furthermore, since the dissolved silica in the alkaline activators was the same, the workability and setting times of 95R5S-0.35-2.5-G were comparable to 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G.

Mixture 95N5S-0.35-1.62-V was produced using an industrial grade sodium silicate solution with an MS of 2.32, which was higher than the analytical grade with an MS of 2.0 used to prepare 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G. To best match the oxide ratios of the 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G mixture, the SS/SH solution ratio was changed to 1.6 instead of 2.5. Consequently, the oxide ratios were comparable to the reference mixture with a reactive SiO2/Na2O ratio of 5.8 and a reactive SiO2/reactive Al2O3 ratio of 2.11. A comparison of the oxide ratios of 95R5S-0.35-2.5-G and 95N5S-0.35-1.62-V revealed that mixture 95N5S-0.35-1.62-V had a reactive SiO2/Na2O ratio of 5.8, which was higher than the 5.2 ratio for 95R5S-0.35-2.5-G. This difference in oxide ratios was attributed to fly ash R having a slightly lower reactive silica content than fly ash N, as well as sodium silicate solution V having a higher soluble reactive silica content than sodium silicate solution G. The 28 days compressive strengths of the 95N5S-0.35-1.62-V mixture was 61 MPa. Additionally, 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G had comparable workability and setting times to 95N5S-0.35-2.5-V.

Overall, the composition of the activated mixtures 95R5S-0.35-2.5-G and 95N5S-0.35-1.62-V were very comparable to the composition of the mixture 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G in terms of the reactive oxides. The reactive oxide ratio of SiO2 to Al2O3 was kept close to 2.0. Additionally, the silica content in the alkaline activator was close to 0.33. The concentration of NaOH in the alkaline activator was maintained higher than 3.0 M. The 28-day compressive strengths from all the mixtures were higher than 60 MPa.

Discussions

Fly Ash mixes

Considering the ranges of compositional variables defining the alkaline activating solution, increasing the SS/SH ratio increased the silica content (the dissolved silica). Furthermore, as the SS/SH ratio increased, the concentration of NaOH in the alkaline activator decreased. The concentration of NaOH in the alkaline activator is presented in Table 4. NaOH contributes to the alkaline activator’s basicity and total sodium content. However, the changes in the basicity within the molarity range considered in this study have no influence on early strength development. The accelerating effect of the increasing NaOH molarity are likely offset by the retarding effect of the increasing dissolved silica in the alkaline activator.

In pastes proportioned based on total reactive oxide ratios, the dissolved silica content in the alkaline activator appears to be the key factor influencing fresh properties and 28-day strength. For ambient curing, a higher 28-day strength is obtained for a higher dissolved silica content in the alkaline activator. Obtaining higher strength from the activated fly ash therefore requires increasing the amount of dissolved silica in the alkaline activator, which would however, increase the viscosity and delay the setting. Increasing the SS/SH ratio beyond 2.5 led to a negligible improvement in strength. Considering the composition of mixture 100N0S-0.35-2.5-G, the reactive SiO2/Na2O and the reactive SiO2/reactive Al2O3 ratios were 5.4 and 2.08, respectively.

Fly Ash and slag mixes

The main reaction product formed in activated pastes containing 5% slag in the binder is NASH. Typical SEM micrograph of the 28-day sample of 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G is shown in Fig. 9. A dense microstructure which is typical of the amorphous geopolymers is seen. The unreacted fly ash is seen in the form of spherical glassy particles. The morphology of the reaction products confirms the presence of NASH as the primary reaction product that was indicated by the XRD analysis. Unreacted or partially reacted fly ash and slag particles appear as irregular morphologies.

The early reactivity in the binders consisting of fly ash and slag is due to slag hydration. The addition of slag primarily influenced the early reactivity and strength gain in the activated binder. The addition of slag resulted in higher heat generation in the mixture 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G compared to 100N0S-0.35-2.5-G due to the higher early kinetic activity of slag in the binder. The early dissolution of slag glassy phase in the binary binder leads to the release of Ca2+ into the activating solution. The presence of Ca2+ from slag promotes dissolution of vitreous phases in fly ash and subsequently the additional silica from slag contributes to geopolymerisation. The Ca2+ elevates the pH locally, which increases the solubility of fly ash. The early hydration of slag likely produced calcium aluminosilicate hydrate (CASH) gel within the activated system. Previous studies have shown that in the presence of Ca2+, CASH is preferentially formed even if a sodium-based alkaline activator is used44. The CASH formed in the activated paste containing 5% slag in the binder is responsible for improvements in setting and early strength gain. The availability of calcium supply is, however, insufficient to sustain the continued production of CASH gel. Previous studies that used higher proportion of slag, 20% and higher of the total binder reported continued formation of CASH, while Na+ remained in a free form27. The Na based geopolymers did not form in the presence of higher quantities of Ca2+. At a small proportion of slag in the binder, in the range of 5%, the slag contributes additional silica to the activated mixture, assisting in the formation of NASH content once the Ca2+ supplied by slag is depleted. The formation of reaction products increased steadily in activated pastes with and without slag. However, 95N5S-0.35-2.5-G had a higher NASH content at all ages, which contributes to a higher compressive strength at all ages than 100N0S-0.35-2.5-G.

The outcomes of this study are summarised in a schematic phase diagram as shown in Fig. 10. The required composition of the alkaline activator is determined based on the reactive SiO2 and reactive Al2O3 contents in the fly ash. The results indicated that keeping the reactive oxide ratios of the activated system in the range of reactive SiO2/Na2O ≥ 5 and reactive SiO2/reactive Al2O3 ≥ 2.0 can result in producing high compressive strength and optimal fresh properties in fly ash binders. The procedure can be used as a guideline; however, further research is required to fully optimise the process.

Conclusions

This study presents a consistent approach for producing high strength fly ash based geopolymer binders cured at ambient conditions. The proposed method enables the development of mix designs without the use of heat curing, high NaOH molarity, or excessive cementitious additives, making it more suitable for field applications. The formulation was based on the reactive oxide composition of the raw materials and showed consistent performance across different fly ash and sodium silicate sources.

The key findings of the study are:

-

Fly ash-based geopolymer pastes achieved compressive strengths of up to 61 MPa under room temperature curing without requiring high NaOH molarity or high ratios of cementitious additives.

-

The incorporation of 5% slag further increased the compressive strength by 8.5% and improved the setting times without adversely affecting the workability of the activated system. This enhancement was attributed to greater early-age kinetics and synergistic effects in gel formation.

-

Calorimetry and XRD results showed that slag promoted early NASH formation and minor CASH formation without significantly altering the Na-based geopolymer mechanism. higher heat generation when activated with an alkaline activator. The slag addition contributed to a 2.2% increase in NASH content at 28 days.

-

NASH gel was identified as the main reaction product contributing to strength, with higher formation rates observed in slag containing systems due to increased dissolution of amorphous content in fly ash.

-

Varying fly ash and sodium silicate compositions while regulating oxide ratios of reactive SiO2/Na2O ≥ 5, reactive SiO2/reactive Al2O3 ≥ 2, and a SiO2/H2O mass ratio ≈ 0.33 produced consistent compressive strengths.

Limitations

Future research may consider the following limitations: the study focused on low calcium fly ash with 5% slag; thus, the finding may not be applicable to fly ash with higher calcium content or different percentages of slag. Further, the alkaline activator used in the study was mainly composed of sodium silicate and 8 M NaOH solutions, and alternative solutions were not studied. The compressive strength development was measured at 3, 7, 14, and 28 days, while the 1 day strength was not measured. Moreover, curing conditions were limited to room temperatures, while high curing temperatures were not explored.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Newell, R., Raimi, D., Villanueva, S. & Prest, B. Global energy outlook 2021: Pathways from Paris, in Resources for the Future, vol. 8 (2021).

Valente, M., Sambucci, M. & Sibai, A. Geopolymers vs. cement matrix materials: How nanofiller can help a sustainability approach for smart construction applications—a review. Nanomaterials 11 (8), 2021 (2007). https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11082007

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. Climate change 2021: The physical science basis, in Contribution of working group I to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (2021).

Juenger, M., Winnefeld, F., Provis, J. L. & Ideker, J. Advances in alternative cementitious binders. Cem. Concr. Res. 41 (12), 1232–1243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2010.11.012 (2011).

Nguyen, H. A., Chang, T. P., Shih, J. Y. & Chen, C. T. Formulating for innovative self-compacting concrete with low energy super-sulfated cement used for sustainability development. J. Mater. Sci. Chem. Eng. 4 (7), 22–28. https://doi.org/10.4236/msce.2016.47004 (2016).

Hassan, A., Arif, M. & Shariq, M. Effect of curing condition on the mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. SN Appl. Sci. 1 (12), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1774-8 (2019).

Duxson, P. et al. Geopolymer technology: The current state of the Art. J. Mater. Sci. 42 (9), 2917–2933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10853-006-0637-z (2007).

Wesche, K. Fly Ash in Concrete: Properties and Performance (CRC, 1991).

Nath, S. K. & Kumar, S. Role of particle fineness on engineering properties and microstructure of fly Ash derived geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 233, 117294 (2020).

Diaz, E., Allouche, E. & Eklund, S. Factors affecting the suitability of fly ash as source material for geopolymers, Fuel 89 (5), 992–996 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2009.09.012

Hadi, M. N., Al-Azzawi, M. & Yu, T. Effects of fly Ash characteristics and alkaline activator components on compressive strength of fly Ash-based geopolymer mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 175, 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.04.092 (2018).

Singh, G. V. P. B. & Subramaniam, K. V. L. Evaluation of sodium content and sodium hydroxide molarity on compressive strength of alkali activated low-calcium fly Ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 81, 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2017.05.001 (2017).

Cong, P. & Cheng, Y. Advances in geopolymer materials: A comprehensive review. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtte.2021.03.004 (2021).

Guo, X., Shi, H., Chen, L. & Dick, W. A. Alkali-activated complex binders from class C fly Ash and Ca-containing admixtures. J. Hazard. Mater. 173, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.08.110 (2010).

Bakharev, T. Geopolymeric materials prepared using class F fly Ash and elevated temperature curing. Cem. Concr. Res. 35 (6), 1224–1232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2004.06.031 (2005).

Sindhunata, J., Van Deventer, G., Lukey & Xu, H. Effect of curing temperature and silicate concentration on fly-ash-based geopolymerization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 45 (10), 3559–3568. https://doi.org/10.1021/ie051251p (2006).

Alanazi, H., Hu, J. & Kim, Y. R. Effect of slag, silica fume, and Metakaolin on properties and performance of alkali-activated fly Ash cured at ambient temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 197, 747–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.172 (2019).

John, S. K., Nadir, Y. & Girija, K. Effect of source materials, additives on the mechanical properties and durability of fly Ash and fly Ash-slag geopolymer mortar: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 280, 122443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.122443 (2021).

Bhagath Singh, G. V. P., Subrahmanyam, C. & Subramaniam, K. V. Dissolution of the glassy phase in low-calcium fly Ash during alkaline activation. Adv. Cem. Res. 30 (7), 313–322. https://doi.org/10.1680/jadcr.17.00170 (2018).

Wallah, S. & Rangan, B. V. Low-calcium fly ash-based geopolymer concrete: long-term properties (2006).

Rattanasak, U. & Chindaprasirt, P. Influence of NaOH solution on the synthesis of fly Ash geopolymer. Miner. Eng. 22 (12), 1073–1078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2009.03.022 (2009).

Singh, G. V. P. B. & Subramaniam, K. V. L. Quantitative XRD study of amorphous phase in alkali activated low calcium siliceous fly Ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 124, 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.07.081 (2016).

Puligilla, S. & Mondal, P. Role of slag in microstructural development and hardening of fly ash-slag geopolymer. Cem. Concr. Res. 43, 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2012.10.004 (2013).

Waqas, R. M., Butt, F., Zhu, X., Jiang, T. & Tufail, R. F. A comprehensive study on the factors affecting the workability and mechanical properties of ambient cured fly Ash and slag based geopolymer concrete. Appl. Sci. 11, 18, 8722, (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/app11188722

Nagajothi, S. & Elavenil, S. Effect of GGBS Addition on reactivity and microstructure properties of ambient cured fly ash based geopolymer concrete. Silicon 13 (2), 507–516 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-020-00470-w

Rafeet, A., Vinai, R., Soutsos, M. & Sha, W. Effects of slag substitution on physical and mechanical properties of fly ash-based alkali activated binders (AABs). Cem. Concr. Res. 122, 118–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconres.2019.05.003 (2019).

Reddy, K. C. & Subramaniam, K. V. Investigation on the roles of solution-based alkali and silica in activated low-calcium fly Ash and slag blends. Cem. Concr. Compos. 123, 104175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cemconcomp.2021.104175 (2021).

Bellum, R. R., Al Khazaleh, M., Pilla, R. K., Choudhary, S. & Venkatesh, C. Effect of slag on strength, durability and microstructural characteristics of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. J. Build. Pathol. Rehabil. 7 (1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41024-022-00163-4 (2022).

Zhang, B., Zhu, H., Cheng, Y., Huseien, G. F. & Shah, K. W. Shrinkage mechanisms and shrinkage-mitigating strategies of alkali-activated slag composites: A critical review. Constr. Build. Mater. 318, 125993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2021.125993 (2022).

Pulverized-fuel-ash: Specification for pulverized-fuel-ash for use with portland cement. (British Standards Institution, 1997).

Standard Specification for Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use as a Mineral Admixture in Portland Cement Concrete. (ASTM C-618, 2002).

Tennakoon, C., San Nicolas, R., Sanjayan, J. G. & Shayan, A. Thermal effects of activators on the setting time and rate of workability loss of geopolymers. Ceram. Int. 42 (16), 19257–19268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2016.09.092 (2016).

Bhagath Singh, G. & Subramaniam, K. V. Effect of active components on strength development in alkali-activated low calcium fly Ash cements. J. Sustain. Cem.-Based Mater. 8 (1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/21650373.2018.1520657 (2019).

Hardjito, D. & Rangan, B. V. Development and properties of low-calcium fly ash-based geopolymer concrete (2005).

Standard test method for flow of hydraulic cement mortar. ASTM C 1437–1407 (2008).

Standard test methods for time of setting of hydraulic cement by Vicat needle. ASTM C 191–108 (2008).

Reddy, K. C. & Subramaniam, K. V. Blast furnace slag hydration in an alkaline medium: Influence of sodium content and sodium hydroxide molarity. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 32 (12), 04020371. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0003455 (2020).

Reddy, K. C. & Subramaniam, K. V. L. Quantitative phase analysis of slag hydrating in an alkaline environment. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 53 (2), 424–434. https://doi.org/10.1107/S1600576720001399 (2020).

Kondepudi, K. & Subramaniam, K. V. L. Critical evaluation of rheological behaviour of low-calcium fly Ash geopolymer pastes. Adv. Cem. Res. 34 (3), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1680/jadcr.20.00043 (2022).

Nath, P. & Sarker, P. K. Effect of GGBFS on setting, workability and early strength properties of fly Ash geopolymer concrete cured in ambient condition. Constr. Build. Mater. 66, 163–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.05.080 (2014).

Humad, A. M., Kothari, A., Provis, J. L. & Cwirzen, A. The effect of blast furnace slag/fly Ash ratio on setting, strength, and shrinkage of alkali-activated pastes and concretes. Front. Mater. 6, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2019.00009 (2019).

Nikvar-Hassani, A., Manjarrez, L. & Zhang, L. Rheology, setting time, and compressive strength of class F fly Ash–Based geopolymer binder containing ordinary Portland cement. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 34 (1), 04021375. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)MT.1943-5533.0004008 (2022).

Pawley, G. Unit-cell refinement from powder diffraction scans. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 14 (6), 357–361. https://doi.org/10.1107/S0021889881009618 (1981).

Kamakshi, T. A., Reddy, K. C. & Subramaniam, K. V. Studies on rheology and fresh state behavior of fly ash-slag geopolymer binders with silica. Mater. Struct. 55 (2), 1–15 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-022-01908-w

Gadkar, A. & Subramaniam, K. V. L. An evaluation of yield and Maxwell fluid behaviors of fly ash suspensions in alkali-silicate solutions. Mater. Struct. 52 (117), 1–12 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1617/s11527-019-1429-7

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the joint scholarship support provided by Swinburne University of Technology and the Iraqi Ministry of Higher Education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mustafa Shamsah: PhD student, execution of experimental testing, writing initial draft; Robin Kalfat: Principal supervisor, planning, conceptualization, management, writing, editing; Kolluru V.L. Subramaniam: Co-ordinating supervisor, planning, conceptualization, management, writing, editingMude Hanumananaik: Testing and analysis of reaction kinetics.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shamsah, M., Kalfat, R., Subramaniam, K.V.L. et al. Calcium enhanced ambient cured fly Ash based geopolymer binders. Sci Rep 15, 25603 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07854-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07854-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Ultra-High Strength Geopolymer Concrete from Industrial Waste: Reducing Anhydrous Sodium Silicate and Steel Fiber Effects

Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Civil Engineering (2025)