Abstract

A body of research shows that the human visual system hosts a network specialized in processing social interactions—i.e., physical/communicative exchanges between people. This network largely overlaps with regions involved in motion perception. Current views propose that, since motion is an intrinsic component of social interaction, it is necessary to trigger social-interaction selectivity. However, the relationship between social-interaction perception and motion perception remains unclear. We took advantage of two existing functional MRI datasets collected in the same participants, to identify the social-interaction network, and study how it responds to static versus dynamic visual social scenes. Results showed that scenes showing interacting face-to-face (vs. back-to-back) people elicited greater activity in the extrastriate body area (EBA) and posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS). This facingness effect was observed for both static and dynamic stimuli, indicating that motion is not required to trigger social-interaction selectivity. However, neural activity was stronger for dynamic (vs. static) stimuli, implying that motion enhances the network’s responsiveness. Moreover, the facingness effect was stronger in left hemisphere areas. Thus, while social perception has traditionally been associated with the right hemisphere, the present findings highlight a critical role for left visual areas, raising new questions about their function in social perception.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A social interaction is an event in which at least one agent acts intentionally to affect the state of another agent. The scale, diversity and complexity of human social interactions are unmatched in the animal kingdom. In latest years, cognitive neuroscience research has highlighted specialized mechanisms and brain areas for detecting and processing social interactions in the visual world1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Observing two people looking at, or moving toward each other (i.e., face-to-face or facing) recruits particularly efficient visual perception mechanisms5,8,9,10. In functional MRI (fMRI) studies, visual perception of social interactions has been associated with increased activity in lateral visual areas, overlapping with or adjacent to areas involved in perception of bodies and bodily motion, in the extrastriate body area (EBA) and posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS)1,2,3,4,11,12,13,14,15,16,17.

The replication of the effect across different studies, stimulus-sets and tasks (see Table 1) has made the increased neural response to facing/interacting versus non-facing/non-interacting bodies a reliable signature of social interaction selectivity. This univariate effect with visually matched stimuli (most often, the very same bodies and body movements were presented in the interacting and non-interacting contexts) may reflect additional integrative processing and emerging properties of related/interacting individuals18,19,20. Overall, this body of studies converges on a role of the visual system in the earliest stages of social interaction processing: a network of visual areas would leverage relational cues in the stimulus structure (e.g., spatial positioning of bodies, body postures, distance) to begin the transformative process that goes from body and motion perception to representation of social interaction3,14.

The functional specificity of the areas within this network is currently under investigation. An outstanding question concerns the role of motion. Current views propose that motion is an intrinsic component of social interaction and, therefore, it is necessary to trigger social-interaction selectivity12,39,40,41. This view is supported by the fact that social-interaction selectivity in pSTS was reported in studies using dynamic stimuli21,27,28 (see also Table 1), but not in most studies using static stimuli1,2,11,20,25,31. Other findings however reported an effect in pSTS also for static stimuli22,23. Moreover, while some studies reported an effect in EBA for both static1,2,11,20 and dynamic stimuli3,13,15,38, other studies did not find EBA activity using either static22,23,24,25 or dynamic stimuli29,30,32,33,34,35,36,37 (see also Table 1).

One problem with this inconsistent set of results is that the available studies used either static or dynamic stimuli, making it difficult to compare effects between stimulus modalities, and to conclude on whether, and why, a given region would respond more (or selectively) to one or the other modality.

An exception is the work of Landsiedel and colleagues12, who measured neural activity during perception of both video-clips and static frames of interacting versus non-interacting dyads, and showed social-interaction selectivity in pSTS and EBA in the dynamic (video-clip) condition only. However, as the authors noted, there are at least two ways in which ‘social interaction’ has been operationalized in the current literature. Some studies, including Landsiedel et al.12, used representations of meaningful, fully-fledged dyadic social interactions (compared with individuals acting in isolation), where the interaction was indicated by a variety of cues such as action categories and their coherence, object- and scene-level properties (which objects are involved and where the event takes place) and other contextual cues (e.g., clothing), emotional cues, in addition to merely physical properties, such as distance, motion direction, and/or body orientation14. Other studies instead selected and systematically varied only key ‘prototypical’ physical cues of social interaction such as distance and body orientation, under the hypothesis that the visual system is tuned for quick and accurate perception of nearby face-to-face (vs. non-facing) bodies5,6. On this view, the facing configuration of two bodies would constitute the most basic structure that the visual system readily reads as ‘social interaction’. Thus, the question is: If a visual scene features just two people close together and face-to-face, is motion still necessary to elicit interaction selectivity in EBA and pSTS? This question comes closer to understanding what ‘social interaction’ is for the human visual system.

A way to address this question is to measure neural responses to static and dynamic stimuli that are comparable in terms of physical structure, with just two nearby bodies oriented toward (vs. away from) each other. In this study, we did so, with opportunistic analyses on two existing fMRI datasets measuring neural activity in response to, respectively, static and dynamic body dyads that did not depict any familiar, easy to identify, social interaction, and carry no interaction cues other than facingness. To favor comparison between stimulus sets, our analyses only considered fMRI data from participants who took part in both studies (i.e., with static and dynamic stimuli).

To preview, we found that facing dyads—both static and dynamic—triggered left-lateralized effects in both the lateral occipital cortex overlapping with the EBA, and the pSTS. This effect demonstrates that motion is not a necessary signal to trigger social interaction selectivity in the ‘social interaction’ visual-perception network. Furthermore, left-lateralized effects challenge the common view of a right-hemisphere superiority in social perception, opening new questions about the function of left brain areas in social perception and cognition.

Methods

Participants

Fifteen healthy adults participated in two distinct fMRI sessions as paid volunteers (7 identified themselves as female; 8 identified themselves as male; mean age: 25.2 ± 4.6 SD). They were part of two larger groups involved in two published studies, one involving static stimuli2, and the other involving dynamic stimuli3. All participants had normal or corrected-to-normal vision. They reported no history of medical, psychiatric, or neurological disorders, or use of psychoactive medications. They were screened for contraindications to fMRI and gave informed consent before participation. A sensitivity analysis was conducted using G*Power42 to determine the minimum detectable effect size given the study parameters. Assuming a within-subjects design with 40 conditions, a sample size of N = 15, an alpha level of 0.05, and a desired power of 0.80, the analysis indicated a minimum detectable effect size of f = 0.185. Thus, the study was adequately powered to detect effects in the small-to-medium range. Experimental procedures were approved by the local ethics committee and the study was conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Data collection was carried out at the CERMEP neuroimaging center in Bron, after approval of the ethics committee (Comité de Protection des Personnes—CPP Sud Est V, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire—CHU de Grenoble).

Stimuli

Static stimuli

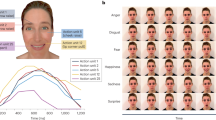

Facing dyads were formed from 16 gray-scale renderings of human bodies (and their mirror version), all in profile view and biomechanically possible poses, for a total of 32 bodies. Single bodies were randomly paired to form 16 facing dyads, and their mirror version, for a total of 32 facing dyads (Fig. 1a). Bodies in each dyad were horizontally flipped to form 32 non-facing dyads. The centers of the two bounding boxes that contained the two bodies in a dyad were equally distant from the center of the image. The distance between two bodies in a dyad was matched across facing and non-facing dyads (meanfacing = 82.88 pixels ± 13.76 SD; meannon-facing = 83.06 ± 13.86; t(15) = 1.00; p > 0.250). In sum, facing and non-facing stimuli were identical except for the relative positioning of the two bodies.

(a) fMRI design for the sessions with static (blue) and the dynamic (red) stimuli. Lines connecting dots in point-light displays were added for visualization purposes only; (b) Results of the whole brain contrast facing > non-facing for static (left) and dynamic (right) stimuli; p = 0.001, FDR-corrected; (c) Results of the conjunction analysis of group-level maps for the contrast facing > non-facing for static (blue) and dynamic (red) stimuli; p = 0.001, FDR-corrected. The conjunction is highlighted in beige. The functionally-defined group-level EBA is highlighted in yellow. The functionally-defined group-level BM-pSTS is highlighted in blue. Activity peak is plotted with a green cross; (d) Region of interest (ROI) analysis in EBA, BM-pSTS, MTV5, PPA and EVC. Error bars denote the within-subjects normalized SEM. ∗p ≤ 0.05; ∗∗p ≤ 0.01; ∗∗∗p ≤ 0.001. Black dots represent each single subject’s mean activity across the ROI. Bars represent mean beta values for facing and non-facing activity across all subjects. Only significance of the configuration effect is plotted. Details of other main effects and interaction can be found in the results section.

Dynamic stimuli

Dynamic stimuli (Fig. 1a) consisted of silent movies of 2000 ms, showing point-light displays (PLDs) of two human bodies performing two different movements. PLDs depict the movements of two bodies by means of few isolated points in correspondence with the major joints of the moving body, thus allowing to isolate and closely control body motion (i.e., kinematic and shape) information43. The movement of each body was depicted by 13 white dots (on a black background) in correspondence with the major joints of the moving body (top of the head, shoulders, elbows, hands, hips, knees, and ankles). The 20 individual PLD-bodies that formed the dyads were selected from a public database44 and randomly paired, yielding 10 facing and 10 non-facing dyads, without any obvious, familiar content. Bodies were oriented toward or away from each other. The distance between the two bodies as well as the average motion energy (i.e., optical flow45) was matched between facing and non-facing dyads (distance: meanfacing = 85 pixels ± 82 SD; meannon-facing = 92 ± 79; t(9) < 1, ns; optical flow: mean magnitudefacing + − sd = 2.19 + − 0.60, mean magnitudenon-facing = 2.21 ± 0.60 SD, t(9) = 1.26, p = 0.24). More details on the stimuli can be found in Abassi and Papeo2 and Bellot et al.3, respectively.

Procedures

Static and dynamic stimuli were presented to participants in two different sessions, performed on different days with an interval of about 1 month between the two sessions (Fig. 1a). The order of the sessions was counterbalanced across participants. The session with static stimuli included blocks of single bodies, single objects, facing and non-facing dyads, all presented upright and inverted (in separate blocks), distributed across six runs (total duration of the experiment: 41 min). For the purposes of this study, we only considered blocks with facing and non-facing dyads, which were presented in three runs, each lasting 6.83 min. Each run consisted of 2 sequences of 16 blocks (4 per condition), yielding a total of 32 blocks. Blocks in the first sequence were presented in a random order, and blocks in the second sequence were presented in the counterbalanced order relative to the first one. Each run began with a 10 s warm-up block and ended with a 16 s cool-down block during which a black fixation cross was presented. The onset time of each block was jittered within a run (range of inter-block interval duration: 2–6 s; total inter-block time by runs: 128 s) using the optseq tool of Freesurfer46 to optimize jittering. Each block consisted of eight 550 ms stimuli of the same condition presented in a random order, separated by a 450 ms interval. Each stimulus appeared once in a block and twice in a run (one in each sequence). A black fixation cross was always present on the screen. Participants were instructed to fixate the cross throughout the experiment and to press a button with their right index finger when the cross turned red (cross changed color in 37% of the stimulation and fixation periods). This task was implemented to minimize eye movements and maintain vigilance in the scanner. During this session, participants also completed two runs of a standard functional localizer task (total duration: 10.54 min) adapted from the fLoc package47, to define, in individual participants, regions of interest (ROIs) responding to visual perception of bodies. Stimuli for this task consisted of 180 grayscale photographs of bodies (headless bodies and body parts), faces, places (houses and corridors), inanimate objects and scrambled objects (see Abassi and Papeo2 for details).

Dynamic stimuli were presented during an event-related fMRI design, including two stimulation runs with PLDs of single bodies and two stimulation runs with PLDs of facing and non-facing body dyads, randomly interleaved (total duration: 34 min 8 s). For the purposes of this study, we only considered trials with facing and non-facing dyads. Facing and non-facing dyads were presented randomly over two functional runs, each lasting 8 min 32 s. Each run consisted of 2 sequences separated by a 16 s interval. Each sequence was composed of 40 stimuli (2 s movies of facing and non-facing dyads), with an inter-stimulus interval (ISI) of 2, 4, of 6 s, each occurring with 1/3 probability. Events in the first sequence were presented in a random order, and events in the second sequence were presented in the counterbalanced order relative to the first one. Each stimulus was repeated twice in a sequence (original view and its flipped version), hence, 8 times across the experiment (4 times in each run). Each run began with a warm-up block (8 s) and ended with a cooldown block (16 s), during which a central fixation cross was presented. To minimize eye movements and maintain vigilance, participants were instructed to fixate the center of the screen and to press a button with their right index finger when the dots forming the point-light displays changed color (dots went from white to light pink in 2.5% of events across a run). During this session, participants also completed two standard functional localizer tasks (total duration: 21 min 32 s). In one task (motion-localizer task), stimuli were arrays of white dots on a black background moving in coherent motion, alternating with arrays of static dots. This task was used to localize the motion-responsive middle temporal visual area (MT/V5) (see48). In the other task (biological motion-localizer task), one condition involved PLDs (white dots on a black background) depicting the motion of a human body; the other condition involved scrambled-PLDs that retained local motion-information (the motion of individual dots) but presented dots in different location relative to the PLD condition, so that human body and motion were no longer recognizable (see48). With this task we localized the pSTS area responsive to biological motion, which is adjacent to and overlapping with pSTS areas showing effects of social interaction (see3,4). However, since neuronal populations with different functional specificities are present in the pSTS, we labeled our functionally-localized pSTS area as ‘BM-pSTS’ (biological-motion pSTS) to be explicit about how this ROI was defined.

In both experiments, stimuli were back-projected onto a translucent screen by a liquid crystal projector (frame rate: 60 Hz; screen resolution: 1024 × 768 pixels, screen size: 40 × 30 cm). Participants viewed the screen binocularly (7° of visual angle) through a mirror above the head coil. Stimulus presentation, response collection, and synchronization with the scanner were controlled with the Psychtoolbox49,50,51 through MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Data acquisition

Imaging was conducted on a MAGNETOM Prisma 3T scanner (Siemens Healthcare). In both sessions (static and dynamic stimuli), T2*-weighted functional volumes were acquired using a gradient-echo-planar imaging (GRE-EPI) sequence (acquisition parameters: repetition time (TR) 2000 ms; echo time (TE) 30 ms, flip angle 80°; acquisition matrix 96 × 92; field of view (FOV) 210 × 201; 56 transverse slices; slice thickness 2.2 mm; no gap; multiband acceleration factor 2; phase encoding set to anterior/posterior direction). T1-weighted images were acquired with an MPRAGE sequence (TR/TE/TI 3000/3.7/1100 ms; flip angle 8°, acquisition matrix 320 × 280; FOV 256 × 224 mm; slice thickness 0.8 mm; 224 sagittal slices, GRAPPA accelerator factor 2). The acquisition of two field maps was performed at the beginning of each fMRI session (both for static and dynamic stimuli sessions). In the session with static stimuli, eight runs were acquired for a total of 1546 frames per participant, for the main experiment and the functional localizer task. In the session with dynamic stimuli, 6 runs were acquired for a total of 1374 images per participant, for the main experiment and the functional localizer task.

Analyses

Preprocessing of B0 inhomogeneity mappings and functional images

fMRI data were treated ex novo using the optimized preprocessing pipeline fMRIPrep 22.0.252,53, based on Nipype 1.8.554,55. One fieldmap was used for each participant. A B0 nonuniformity map (or fieldmap) was estimated from the phase-drift maps measure with two consecutive GRE (gradient-recalled echo) acquisitions. The corresponding phase-maps were phase-unwrapped with prelude (FSL 6.0.5.1:57b01774). The T1-weighted (T1w) image was corrected for intensity non-uniformity (INU), and used as T1w-reference throughout the workflow. Brain extraction, surface reconstruction and brain tissue segmentation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), white-matter (WM) and gray-matter (GM) were performed on the brain-extracted T1w. Volume-based spatial normalization to MNI (Montreal Neurological Institute) standard space was finally performed. For each participant, for each of the functional runs, preprocessing steps included: head motion parameter estimation, slice-timing correction, realignment, and co-registration to the T1w reference. Nuisance covariates such as head-motion parameters, WM and CSF signals were removed, and images were normalized to MNI standard space. After preprocessing, each functional volume was smoothed by a 6mm full-width at half-maximum (FWMH) Gaussian kernel, using a custom-made MATLAB code in combination with SPM1256. Time series for each voxel were high-pass filtered (cutoff 128 s) to remove signal drift and low-frequency noise. Further details on preprocessing are reported as Supplementary material 4.

Whole-brain analysis

For each participant, for each voxel, the BOLD signal was estimated in a general linear model (GLM) using SPM12, separately for the two datasets with static and dynamic stimuli. The GLM for the static dataset modeled two regressors for the two critical conditions—upright facing and non-facing dyads—, two regressors for the inverted facing and non-facing dyads conditions, and six regressors for movement correction parameters as nuisance covariates. For the dynamic dataset, the GLM included two regressors for the conditions with facing and non-facing dyads, and six regressors for movement correction parameters as nuisance covariates. We computed the contrasts facing > non-facing dyads and non-facing > facing dyads for static and dynamic stimuli. Statistical significance of second-level effects was determined using a voxelwise threshold of p < 0.001 with FDR-correction at the cluster level. In addition, subject-specific activity peaks for the facing > non-facing contrast in static and dynamic stimuli were gathered, within a custom-made bilateral mask encompassing EBA and pSTS, to examine the lateralization of these peaks and their proximity with the functionally localized EBA and BM-pSTS in each subject (Fig. 2).

Individual maps for the conjunction (beige) of the facing > non-facing effect with static (blue) and dynamic (dark red) stimuli. Yellow crosses denote the individual’s EBA (from functional localizer data); light blue crosses denote the individual’s BM-pSTS (from functional localizer data); dark blue crosses denote the peak of the individual’s facing > non-facing effect for static stimuli; light pink crosses denote the peak of the facing > non-facing effect for dynamic stimuli. Group-level coordinates were used for defining the BM-pSTS of participant 6, 8 and 13 and the EBA of participant 2 since no reliable cluster was found near these regions.

Conjunction analysis

A conjunction analysis was carried out to identify the neural activity associated with the perception of facing (vs. non-facing) dyads irrespective of the stimulus modality (static or dynamic) and the activity tied to a specific modality. We considered the group-level maps obtained from the facing > non-facing contrasts for each set of stimuli (p < 0.001 at the voxel level, FDR corrected at the cluster level; Table 2), and assigned to each voxel a value of 1, 2 or 3, indicating respectively whether activity was above threshold for both the static and dynamic facing > non-facing contrast, for the dynamic contrast only, or for the static contrast only57. Individual conjunction maps were also plotted with an uncorrected threshold of p < 0.05 to examine subject-specific location of the conjunction (Fig. 2).

ROI definition and analyses

Using data from the functional localizer tasks, five regions of interest (ROIs) were identified in each participant: the extrastriate body areas (EBA), the motion-selective area in the middle temporal visual area (MT/V5), the pSTS region responsive to biological motion (BM-pSTS), the place-selective parahippocampal place area (PPA) and the early visual cortex (EVC). These ROIs were targeted based on previous studies showing social interaction selectivity in regions overlapping with EBA1,2,11,15,17, MT/V512,58 and pSTS3,4,7,28. PPA and EVC were included as control areas, to test for the specificity of the effects in body- or motion-selective ROIs. To define the ROIs, first, in second-level analyses, we found the peaks of activity for the contrasts bodies > other objects for EBA, moving > static dots for MT/V5, PLDs of human motion > scrambled PLDs for BM-pSTS, places > other objects (faces, bodies, inanimate objects) for PPA, and all objects > baseline for EVC. Second, around these MNI-peak coordinates, for each ROI, we defined a sphere of 10-mm diameter (Marsbar Toolbox in SPM1259,60. All ROIs were defined bilaterally. Third, the spherical ROIs were used as masks to constrain the individual ROIs using the functional t-maps for the contrasts of interest of each subject. For each subject, voxels that were activated by given contrast (e.g., bodies > other objects) and that fell within the mask, were ranked based on t values; the 100 best voxels with a positive t value were included in the ROI. This process was performed separately for the two hemispheres. Overlapping voxels between two ROIs were removed (see supplementary Table S2).

For each participant, for each stimulus modality (static and dynamic), mean activity values (β-weights minus baseline) for facing and non-facing dyads were extracted from each left and right ROI, and analyzed in a 2 hemisphere × 5 ROI × 2 stimulus modality × 2 configuration repeated-measures ANOVA. Critical comparisons were performed with pairwise t tests (p < 0.05, two-tail). In addition to the frequentist ANOVA, Bayes Factors (BF10) were computed for each main effect and interaction to quantify the relative evidence for including stimulus modality as a factor in the model. For each comparison, we contrasted the model including the stimulus modality term with the corresponding model excluding it. The resulting Bayes Factors (BF10) reflect the probability of the data are under one model compared to the other. Interpretation of Bayes Factors followed conventional guidelines61.

Results

Effect of facingness for static and dynamic stimuli

We first examined the effect of body configuration (facing vs. non-facing) separately for each stimulus modality (static and dynamic). With static stimuli, the whole-brain contrast facing > non-facing revealed activity in a left-lateralized network centered in the lateral middle occipitotemporal gyrus, overlapping with the functionally-localized EBA (Table 2; Fig. 1b). The same contrast for dynamic stimuli revealed activity in a wider cluster encompassing the middle occipitotemporal gyrus bilaterally, and the left superior parietal lobule (Table 2; Fig. 1b.), showing that motion indeed increased the overall responsiveness of the network to social interactions. The contrast non-facing versus facing revealed activity in the left posterior occipital lobe for dynamic stimuli only (Table 2; unthresholded activity maps are provided in Supplementary Fig. S1).

The conjunction of the activation maps for the facing > non-facing contrast for static and dynamic stimuli revealed activity in the left middle occipitotemporal cortex, which overlapped with the functionally-localized EBA (Fig. 1c). At the individual-subject level, we observed that peaks were more often localized in the left hemisphere (number of subjects: staticleft = 8; staticright = 7; dynamicleft = 13; dynamicright = 2; see Fig. 2). Conjunction maps for individual subjects, with activity peaks for the static and dynamic contrast [facing > non-facing] and functionally-localized EBA and BM-pSTS, are plotted in Fig. 2. To extract these peaks for each participant we (1) computed the first-level contrasts [bodies > other objects] and [biological motion > scrambled motion]; (2) identified the clusters in the left and right hemisphere closest to the anatomical locations, based on probabilistic maps (i.e. meta-analysis from Neurosynth.org, search terms ‘occipitotemporal cortex’ and ‘pSTS’), of the EBA (i.e. lateral occipitotemporal cortex) and pSTS (i.e. posterior part of the sulcus), respectively (3) extracted the coordinates of the peak voxel in each cluster. MNI coordinates of EBA, BM-pSTS and peaks can be found in the supplementary Table S1.

Effect of facingness for static and dynamic stimuli in motion- and body-perception ROIs

The ANOVA showed the main effects of hemisphere (meandifference ± sd = 1.56 ± 1.46; F1,14 = 16.93, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.55, Bayes Factor (BF10) = 8.11e + 10), ROI (F4,56 = 51.36, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.79, BF10 = 6.85e + 25), stimulus modality (meandifference ± sd = 3.46 ± 2.39; F1,14 = 31.46, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.69, BF10 = 1.76e + 27) and configuration (meandifference ± sd = 0.59 ± 0.84; F1,14 = 7.43, p = 0.016, ηp2 = 0.35, BF10 = 4.75e + 10), indicating that overall activity was stronger in the left (vs. right) hemisphere, differed across ROIs, and was stronger for dynamic (vs. static stimuli) and for facing (vs. non-facing) stimuli.

A significant interaction between ROI and stimulus modality (F4,56 = 6.63, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.32, BF10 = 510.28) showed that all ROIs but the EBA responded more strongly to dynamic than static stimuli (EBA: meandifference ± sd = 2.55 ± 4.92, CI [− 0.18;5.27], t(14) = 2.01, p = 0.065, d = 0.52; BM-pSTS: 2.85 ± 2.29, CI [1.58;4.12], t(14) = 4.82, p < 0.001, d = 1.24; MTV5: 4.50 ± 3.78, CI [2.41;6.59], t(14) = 4.61, p < 0.001, d = 1.19; PPA: 1.64 ± 1.16, CI [0.99;2.29], t(14) = 5.47, p < 0.001, d = 1.41; EVC: 5.77 ± 2.86, CI [4.19;7.36], t(14) = 7.81, p < 0.001, d = 2.02), but the difference was stronger in MTV5 as compared to BM-pSTS (1.65 ± 2.73, CI [0.13;3.16], t(14) = 2.33, p = 0.035, d = 0.60) and PPA (2.85 ± 3.89, CI [0.70;5.01], t(14) = 2.84, p = 0.01 , d = 0.73), and in EVC as compared to BM-pSTS (2.92 ± 2.99, CI [1.26;4.58], t(14) = 3.78, p = 0.002, d = 0.98) and to PPA (4.13 ± 2.93, CI [2.51;5.75], t(14) = 5.46, p < 0.001, d = 1.41). The Stimulus Modality did not interact with any other factor including Hemisphere.

Instead, we found significant interactions between Hemisphere and ROI (F4,56 = 3.18, p = 0.020, ηp2 = 0.19, BF10 = 4.58e + 27), Hemisphere and Configuration (F1,14 = 17.21, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.55, BF10 = 7.21e + 10) and ROI and Configuration (F4,56 = 10.32, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.42, BF10 = 1.33e + 26). These interactions were qualified by a significant three-way interaction between Hemisphere, ROI and Configuration (F1,14 = 4.94, p = 0.002, ηp2 = 0.26, BF10 = 1.06e + 28). All other interactions were not significant (Hemisphere x Stimulus modality: F1,14 = 0.02, p = 0.885 , ηp2 < 0.01, BF10 = 0.12; Stimulus modality x Configuration: F1,14 = 0.18, p = 0.674, ηp2 = 0.01, BF10 = 0.13; Hemisphere x ROI x Stimulus modality: F4,56 = 1.07, p = 0.379 , ηp2 = 0.07, BF10 = 0.04; Hemisphere × Stimulus modality × Configuration: F1,14 = 0.06, p = 0.805, ηp2 < 0.01, BF10 = 0.18; ROI × Stimulus Modality × Configuration: F4,56 = 0.11, p = 0.980, ηp2 < 0.01, BF10 = 0.02; ROI × Stimulus modality × Configuration × Hemisphere: F4;56 = 1.49, p = 0.219, ηp2 = 0.10, BF10 = 0.06).

First, the above results showed that whether stimuli were static or dynamic did not seem to affect the lateralization of social interaction selectivity. In line with this, the BF10 (Bayes factors) reported above showed decisive evidence in favor of the three-way interaction between ROI, hemisphere and stimulus modality, but also substantial to very strong evidence for the lack of interaction of stimulus modality with configuration or other factors.

Second, to investigate the three-way interaction further, we considered to what extent the social interaction selectivity differed between the homologous left and right ROIs. As shown in Fig. 1d, the facing > non-facing effect was especially stronger in the left (vs. right) EBA, BM-pSTS and MT, with no difference between static and dynamic stimulus-conditions. Statistics (i.e., Hemisphere x Configuration ANOVAs run for each ROI separately) confirmed this observation.

EBA

The ANOVA revealed significant main effects of hemisphere (meandifference ± sd = 2.34 ± 3.71; F1,14 = 6.00, p = 0.028, ηp2 = 0.23) and configuration (meandifference ± sd = 1.26 ± 1.17; F1,14 = 17.29, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.46), and a significant interaction between hemisphere and configuration (F1,14 = 31.35, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.43), showing that the difference between facing and non-facing dyads was significant in both left and right ROIs (left: meandifference ± sd = 1.83 ± 1.35, CI [1.09;2.58], t(14) = 5.26, p < 0.001, d = 1.36; right: 0.69 ± 1.12, CI [0.07;1.31], t(14) = 2.39, p = 0.031, d = 0.62), but it was stronger in the left side.

MT/V5

The ANOVA revealed a main effect of configuration (meandifference ± sd = 0.76 ± 1.00, F1,14 = 8.72, p = 0.010, ηp2 = 0.43), no effect of hemisphere (meandifference ± sd = 0.97 ± 4.20, F1,14 = 0.80, p = 0.385, ηp2 = 0.07), and a significant interaction between hemisphere and configuration (F1,14 = 6.78, p = 0.021, ηp2 = 0.23). Like in the EBA, in the MT/V5, the facing > non-facing effect was significant in both sides, but stronger in the left (left: meandifference ± sd = 0.99 ± 1.24, CI [0.31,1.68], t(14) = 3.11, p = 0.008, d = 0.80; right: meandifference ± sd = 0.53 ± 0.84, CI [0.07,0.99], t(14) = 2.45, p = 0.028, d = 0.63).

BM-pSTS

Like MT/V5, BM-pSTS showed a main effect of configuration (meandifference ± sd = 0.98 ± 0.81, F1,14 = 22.03, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.83), no main effect of hemisphere (meandifference ± sd = 1.50 ± 2.74, F1,14 = 4.51, p = 0.052, ηp2 = 0.50), and an significant interaction (F1,14 = 22.66, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.72), showing that the facing > non-facing effect was significant in both sides but stronger in the left (left: meandifference ± sd = 1.50 ± 1.12, CI [0.88;2.13], t(14) = 5.18, p < 0.001, d = 1.33; right: meandifference ± sd = 0.45 ± 0.64, CI [0.10;0.80], t(14) = 2.74, p = 0.016, d = 0.71).

PPA and EVC

We found a main effect of hemisphere in EVC (left > right; meandifference ± sd = 3.16 ± 1.70, F1,14 = 51.84, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.86). No other effect was significant in EVC (configuration: meandifference ± sd = 0.01 ± 1.68, F1,14 = 0.01, p = 0.907, ηp2 < 0.01; interaction: F1,14 = 0.10, p = 0.752, ηp2 < 0.01). No effect was significant in the PPA (hemisphere: F1,14 = 3.53, p = 0.08, ηp2 = 0.97; configuration: F1,14 < 0.01, p = 0.999, ηp2 < 0.01; interaction: F1,14 = 1.27, p = 0.278, ηp2 = 0.86).

Discussion

There is growing evidence of the existence of a specialized network for processing of third-party social interactions, rooted in visual perception and in visual cortex 6,7,14,41,62, and unfolding along a lateral occipitotemporal pathway, from V1 to EBA, MT/V5 and BM-pSTS. Here, we highlighted this network by contrasting the neural response to viewing interacting vs. non-interacting individuals. Moreover, we tested whether social interaction selectivity —i.e., the stronger response to interacting versus non-interacting bodies—was affected by the stimulus modality; particularly, we asked whether motion is a necessary stimulus property, or the mere perception of two bodies close together and oriented towards each other is sufficient to elicit social interaction selectivity (see for discussions on this issue12,39,40,41,61). Results showed that (i) despite the overall greater activity elicited by dynamic stimuli, no reliable difference was observed between dynamic and static stimuli in the degree of social interaction selectivity in the network encompassing the EBA and pSTS; (ii) social interaction selectivity was found even though stimuli did not depict meaningful, fully-fledged, easy to identify, social interactions; and (iii) it was stronger in the left than in the right hemisphere, for both static and dynamic stimuli.

The present study is the first to compare the effect of social interaction selectivity between static and dynamic representations of social interactions, for minimal social scenes featuring just two people close together and face-to-face. This comparison established that a pathway of areas in the lateral visual cortex is tuned to visual scenes that carry basic, reliable cues of social interaction, such as facingness between two nearby individuals6,63,64,65, without further perceptual and non-perceptual cues to aid social interaction recognition and specify the content of interaction. Among other cues, motion has been proposed to play a key role in social interaction perception. One argument for this claim is that, in real world, social interactions typically are dynamic events, and therefore motion cues are part of the routine processing and recognition of social interactions. In effect, regions along the visual pathway that respond to perception of social interactions are also implicated in processing motion, in extracting action/movement representation combining body-posture and motion information (through connections between EBA and pSTS3), and respond more strongly to moving than static faces and bodies41.

The most direct evidence in favor of a key role of motion in social interaction perception was reported in Landsiedel et al.12, who found selectivity to social interactions in EBA and pSTS, only for dynamic representations of social interaction (video-clips), but not for their static counterpart (photos of the most informative frame of a clip). While both Landsiedel et al. and the present study compared effects between static and dynamic stimuli, a critical difference is that, here, we reduced social interaction to a ‘critical minimum’ (i.e., facingness with spatial proximity); instead, Landsiedel et al. used naturalistic every-day social scenes, in which the interaction was conveyed by a rich set of cues (visuo-spatial such as distance, body posture and orientation, and contextual such as objects, place, clothing), which did not necessarily include the ‘critical minimum’ (e.g., in Fig. 1 of Landsiedel et al. two people interact in a street without ever being face-to-face). We can confidently exclude that, in our study, the lack of an effect of motion on the selectivity to social interaction reflects possible limitations of the study. At least, despite the small sample size, our dataset had sufficient statistical power to detect small-to-medium effects (see “Participants” section); and, Bayesian statistics supported the lack of interaction between stimulus modality and configuration (see “Results” section). Thus, the present results showed a critical effect of facingness in triggering the selectivity to social interaction, which generalized across stimuli that were very visually different: static human bodies and animated point-light-displays. In this light, a possible synthesis of the available results is that the visual system is tuned to the perception of bodies that carries prototypical cues of social interaction such as facingness; the presence of such cues is sufficient to trigger the social-interaction perception pathway up to the pSTS, even in the absence of motion information. This empirical fact is consistent with the astonishing human ability to detect social interactions5,8, categorize them66, judge their coherence67,68, and assign roles (agent/patient) to the event participants69,70,71, upon brief presentation (even 33 ms) of static visual images, provided that those images carry prototypical cues of interaction such as facingness, spatial proximity and/or contact.

While facingness has been extensively investigated as a basic social interaction cue6,10,72,73, it is likely not the only ‘social primitive’14. Motion, particularly self-propelled motion, remains a typical and important component of social interaction, however, it might be too unspecific to be a reliable ‘social primitive’, as it is a property of biological agents74, whether they do or do not interact with each other. An exhaustive list of ‘social primitives’ will advance our understanding of how representations of social interactions can be constructed in the human mind/brain as well as in artificial systems75.

Results from whole-brain, conjunction, and region of interest analysis also showed stronger social interaction selectivity in the left than right visual areas, for both static and dynamic stimuli. This left-lateralization of the effect is at variance with the broad literature suggesting a prominent role of the right hemisphere in social vision, i.e., the visual perception of social stimuli such as faces, bodies and biological motion76,77,78,79,80,81 and social cognition (e.g., in theory-of-mind tasks82,83).

Focusing on perception of social interactions, while the earliest reports emphasized a selective involvement of right visual areas4,7, strong claims for right-lateralized effects have vanished in more recent studies1,2,11,12,17,37 (see Table 1). One possibility is that perception of social interaction is less right-lateralized than initially thought, or not at all. Here, however, we found evidence for a left-lateralization of the effects. This circumstance is in line with recent research showing that disrupting left EBA activity with transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) alters visual discrimination of face-to-face (vs. back-to-back) bodies20. Stimuli in that TMS study20 were analogous the static set used here. Thus, one hypothesis is that left-lateralized selectivity is associated with the perception of stimuli that carry prototypical cues of social interaction (i.e., facingness and spatial proximity), while right activity is triggered by richer stimuli that specify the content of the interaction. Encouraging this thinking, our review of the literature (Table 1) suggests that studies reporting right-lateralized or bilateral effects in visual areas involved meaningful, easy to identify, dyadic social interactions, or naturalistic depictions of social scenes, while more basic visual representations of social interactions mainly triggered left lateralized effects.

This circumstance suggests the intriguing idea of a division of labor within the social-interaction perception system, where left areas encode the semantic (or thematic) structure of the interaction based on spatial and postural relations that define the number of participants and their role in the event, while right areas encode information relevant for narrower event-category distinctions (e.g., helping vs. hindering4,7), attribution of goals and intentions and other social-semantic contents. Our stimuli, reducing social interactions to the ‘critical minimum’, would drive activity in left areas, while missing the additional information that specifies event category, goals and intentions, supporting mind reading and other social-cognitive operations.

The results discussed here support the existence of a pathway that, with a sequence of hierarchically-organized stages, moves from processing visual features of social interactions to processing higher-level properties3,14,41. Researchers in the field have an exciting road ahead of them to determine how many functionally different regions exist along this pathway, what their functions are, and how these functions are integrated to represent social interaction. Moreover, all the brain areas targeted in this study—and in this research field more generally—are well known for functions other than social-interaction perception. For example, EBA is known for its role in body/body part perception and MT is known for its role in motion perception. Since the very same bodies and body motion are involved in facing and non-facing stimuli (see “Stimuli” section), what accounts for the effects of facingness in these areas? The available results do not provide an answer to this question, but they clearly show that current knowledge does not exhaust the functions of those brain areas that have been studied for several decades now. Another challenge will be to explain the inter-hemispheric dynamics that integrate information from the right and left regions of this pathway, recognizing that there is a specific place for the left hemisphere in the social brain.

Data availability

Stimuli, analysis codes and supplementary materials associated with this article can be found online at https://osf.io/mbzfs/?view_only=33c30f08f9b84a8692bdb59fd3945497.

References

Abassi, E. & Papeo, L. The representation of two-body shapes in the human visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 40, 852–863 (2020).

Abassi, E. & Papeo, L. Behavioral and neural markers of visual configural processing in social scene perception. Neuroimage 260, 119506 (2022).

Bellot, E., Abassi, E. & Papeo, L. Moving toward versus away from another: How body motion direction changes the representation of bodies and actions in the visual cortex. Cereb. Cortex 31, 2670–2685 (2021).

Isik, L., Koldewyn, K., Beeler, D. & Kanwisher, N. Perceiving social interactions in the posterior superior temporal sulcus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E9145–E9152 (2017).

Papeo, L., Stein, T. & Soto-Faraco, S. The two-body inversion effect. Psychol. Sci. 28, 369–379 (2017).

Papeo, L. Twos in human visual perception. Cortex 132, 473–478 (2020).

Walbrin, J., Downing, P. & Koldewyn, K. Neural responses to visually observed social interactions. Neuropsychologia 112, 31–39 (2018).

Papeo, L. & Abassi, E. Seeing social events: The visual specialization for dyadic human–human interactions. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 45, 877–888 (2019).

Xu, Z., Chen, H. & Wang, Y. Invisible social grouping facilitates the recognition of individual faces. Conscious. Cogn. 113, 103556 (2023).

Vestner, T., Tipper, S., Hartley, T., Over, H. & Rueschemeyer, S.-A. Bound Together: Social binding leads to faster processing, spatial distortion and enhanced memory of interacting partners. J. Vis. 18, 448 (2018).

Abassi, E. & Papeo, L. Category-selective representation of relationships in the visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 44, e0250232023 (2024).

Landsiedel, J., Daughters, K., Downing, P. E. & Koldewyn, K. The role of motion in the neural representation of social interactions in the posterior temporal cortex. Neuroimage 262, 119533 (2021).

Lee Masson, H., Chen, J. & Isik, L. A shared neural code for perceiving and remembering social interactions in the human superior temporal sulcus. Neuropsychologia 196, 108823 (2024).

McMahon, E., Bonner, M. F. & Isik, L. Hierarchical organization of social action features along the lateral visual pathway. Curr. Biol. 33, 5035-5047.e8 (2023).

Walbrin, J. & Koldewyn, K. Dyadic interaction processing in the posterior temporal cortex. Neuroimage 198, 296–302 (2019).

Wurm, M. F. & Caramazza, A. Lateral occipitotemporal cortex encodes perceptual components of social actions rather than abstract representations of sociality. Neuroimage 202, 116153 (2019).

Wurm, M. F., Caramazza, A. & Lingnau, A. Action categories in lateral occipitotemporal cortex are organized along sociality and transitivity. J. Neurosci. 37, 562–575 (2017).

Adibpour, P., Hochmann, J.-R. & Papeo, L. Spatial relations trigger visual binding of people. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 33, 1343–1353 (2021).

Goupil, N., Hochmann, J.-R. & Papeo, L. Intermodulation responses show integration of interacting bodies in a new whole. Cortex 165, 129–140 (2023).

Gandolfo, M. et al. Converging evidence that left extrastriate body area supports visual sensitivity to social interactions. Curr. Biol. 34, 343-351.e5 (2024).

Schultz, J., Imamizu, H., Kawato, M. & Frith, C. D. Activation of the human superior temporal gyrus during observation of goal attribution by intentional objects. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 16, 1695–1705 (2004).

Walter, H. et al. Understanding intentions in social interaction: The role of the anterior paracingulate cortex. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 16, 1854–1863 (2004).

Kujala, M. V., Carlson, S. & Hari, R. Engagement of amygdala in third-person view of face-to-face interaction. Hum. Brain Mapp. 33, 1753–1762 (2012).

Quadflieg, S., Gentile, F. & Rossion, B. The neural basis of perceiving person interactions. Cortex 70, 5–20 (2015).

Pierno, A. C., Becchio, C., Turella, L., Tubaldi, F. & Castiello, U. Observing social interactions: The effect of gaze. Soc. Neurosci. 3, 51–59 (2008).

Atkinson, A. P. & Vuong, Q. C. Incidental visual processing of spatiotemporal cues in communicative interactions: An fmri investigation. Imag. Neurosci. 1, 1–25 (2023).

Schultz, J., Friston, K. J., O’Doherty, J., Wolpert, D. M. & Frith, C. D. Activation in posterior superior temporal sulcus parallels parameter inducing the percept of animacy. Neuron 45, 625–635 (2005).

Lee Masson, H. & Isik, L. Functional selectivity for social interaction perception in the human superior temporal sulcus during natural viewing. Neuroimage 245, 118741 (2021).

Iacoboni, M. et al. Watching social interactions produces dorsomedial prefrontal and medial parietal BOLD fMRI signal increases compared to a resting baseline. Neuroimage 21, 1167–1173 (2004).

Castelli, F., Happé, F., Frith, U. & Frith, C. Movement and mind: A Functional imaging study of perception and interpretation of complex intentional movement patterns. Neuroimage 12, 314–325 (2000).

Centelles, L., Assaiante, C., Nazarian, B., Anton, J.-L. & Schmitz, C. Recruitment of both the mirror and the mentalizing networks when observing social interactions depicted by point-lights: A neuroimaging study. PLoS ONE 6, e15749 (2011).

Georgescu, A. L. et al. Perceiving nonverbal behavior: Neural correlates of processing movement fluency and contingency in dyadic interactions. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35, 1362–1378 (2014).

Lahnakoski, J. M. et al. Naturalistic fMRI mapping reveals superior temporal sulcus as the hub for the distributed brain network for social perception. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 6, 233 (2012).

Lee Masson, H., Van De Plas, S., Daniels, N. & Op De Beeck, H. The multidimensional representational space of observed socio-affective touch experiences. Neuroimage 175, 297–314 (2018).

Santos, N. S. et al. Animated brain: A functional neuroimaging study on animacy experience. Neuroimage 53, 291–302 (2010).

Sapey-Triomphe, L.-A. et al. Deciphering human motion to discriminate social interactions: A developmental neuroimaging study. Soc. Cognit. Affect. Neurosci. 12, 340–351 (2017).

Walbrin, J., Mihai, I., Landsiedel, J. & Koldewyn, K. Developmental changes in visual responses to social interactions. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 42, 100774 (2020).

Dolcos, S., Sung, K., Argo, J. J., Flor-Henry, S. & Dolcos, F. The power of a handshake: Neural correlates of evaluative judgments in observed social interactions. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 24, 2292–2305 (2012).

McMahon, E. & Isik, L. Abstract social interaction representations along the lateral pathway. Trends Cogn. Sci. 28, 392–393 (2024).

Papeo, L. What is abstract about seeing social interactions?. Trends Cogn. Sci. 28, 390–391 (2024).

Pitcher, D. & Ungerleider, L. G. Evidence for a third visual pathway specialized for social perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 25, 100–110 (2021).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191 (2007).

Johansson, G. Visual perception of biological motion and a model for its analysis. Percept. Psychophys. 14, 201–211 (1973).

Manera, V., Von Der Lühe, T., Schilbach, L., Verfaillie, K. & Becchio, C. Communicative interactions in point-light displays: Choosing among multiple response alternatives. Behav. Res. 48, 1580–1590 (2016).

Lucas, B. D. & Kanade, T. An iterative image registration technique with an application to stereo vision. in Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI '81), Vol. 2, 674–679 (1981).

Fischl, B. FreeSurfer. Neuroimage 62, 774–781 (2012).

Stigliani, A., Weiner, K. S. & Grill-Spector, K. Temporal processing capacity in high-level visual cortex is domain specific. J. Neurosci. 35, 12412–12424 (2015).

Papeo, L. & Lingnau, A. First-person and third-person verbs in visual motion-perception regions. Brain Lang. 141, 135–141 (2015).

Brainard, D. H. The psychophysics toolbox. Spat. Vis. 10, 433–436 (1997).

Pelli, D. G. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: Transforming numbers into movies. Spat. Vis. 10, 437–442 (1997).

Kleiner, M., Brainard, D. & Pelli, D. “What’s new in Psychtoolbox-3?” Perception 36 ECVP Abstract Supplement (2007).

Esteban, O. et al. fMRIPrep: A robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nat. Methods 16, 111–116 (2019).

Esteban, O. et al. “fMRIPrep 23.2.0.” Software. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.852659 (2018).

Gorgolewski, K. et al. Nipype: A flexible, lightweight and extensible neuroimaging data processing framework in python. Front. Neuroinform. 5, 13 (2011).

Gorgolewski, K. et al. Nipype. Software https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.596855 (2018).

Friston, K. J. Statistical Parametric Mapping: The Analysis of Functional Brain Images (Elsevier/Academic Press, 2007).

Nichols, T., Brett, M., Andersson, J., Wager, T. & Poline, J.-B. Valid conjunction inference with the minimum statistic. Neuroimage 25, 653–660 (2005).

Tsantani, M., Yon, D. & Cook, R. Neural representations of observed interpersonal synchrony/asynchrony in the social perception network. J. Neurosci. 44, e2009222024 (2024).

Brett, M., Anton, J. L., Valabregue, R. & Poline, J. B. Region of interest analysis using the MarsBar toolbox for SPM 99. Neuroimage 16(2), S497 (2002).

Brett, M., Anton, J. L., Valabregue, R. & Poline, J. B. Region of interest analysis using an SPM toolbox. in 8th International Conference on Functional Mapping of the Human Brain, Vol. 16, No. 2, p. 497 (2002).

Jarosz, A. F. & Wiley, J. What are the odds? A practical guide to computing and reporting bayes factors. J. Probl. Solv. 7, 2 (2014).

McMahon, E. & Isik, L. Seeing social interactions. Trends Cogn. Sci. 27, 1165–1179 (2023).

Hall, E. T. A system for the notation of proxemic behavior1. Am. Anthropol. 65, 1003–1026 (1963).

Zhou, C., Han, M., Liang, Q., Hu, Y.-F. & Kuai, S.-G. A social interaction field model accurately identifies static and dynamic social groupings. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 847–855 (2019).

Peperkoorn, L. S. et al. The prevalence of dyads in social life. PLoS ONE 15, e0244188 (2020).

Hafri, A., Papafragou, A. & Trueswell, J. C. Getting the gist of events: Recognition of two-participant actions from brief displays. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 142, 880–905 (2013).

Dobel, C., Glanemann, R., Kreysa, H., Zwitserlood, P. & Eisenbeiß, S. Visual encoding of coherent and non-coherent scenes. In Event Representation in Language and Cognition (eds Bohnemeyer, J. & Pederson, E.) 189–215 (Cambridge University Press, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511782039.009.

Dobel, C., Gumnior, H., Bölte, J. & Zwitserlood, P. Describing scenes hardly seen. Acta Physiol. (Oxf) 125, 129–143 (2007).

Hafri, A., Trueswell, J. C. & Strickland, B. Encoding of event roles from visual scenes is rapid, spontaneous, and interacts with higher-level visual processing. Cognition 175, 36–52 (2018).

Vettori, S., Odin, C., Hochmann, J.-R. & Papeo, L. A perceptual cue-based mechanism for automatic assignment of thematic agent and patient roles. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 154, 787–798 (2025).

Papeo, L. et al. Abstract thematic roles in infants’ representation of social events. Curr. Biol. 34, 4294-4300.e4 (2024).

Goupil, N., Kaiser, D. & Papeo, L. Category-specific effects of high-level relations in visual search. J. Exp. Psychol.: Hum. Percept. Perform. 51(6), 696–709 (2025).

Goupil, N. et al. Visual preference for socially relevant spatial relations in humans and monkeys. Psychol. Sci. 35, 681–693 (2024).

Csibra, G., Gergely, G., Biró, S., Koós, O. & Brockbank, M. Goal attribution without agency cues: The perception of ‘pure reason’ in infancy. Cognition 72, 237–267 (1999).

Malik, M. & Isik, L. Relational visual representations underlie human social interaction recognition. Nat. Commun. 14, 7317 (2023).

Rossion, B., Hanseeuw, B. & Dricot, L. Defining face perception areas in the human brain: A large-scale factorial fMRI face localizer analysis. Brain Cogn. 79, 138–157 (2012).

De Winter, F.-L. et al. Lateralization for dynamic facial expressions in human superior temporal sulcus. Neuroimage 106, 340–352 (2015).

Pitcher, D., Dilks, D. D., Saxe, R. R., Triantafyllou, C. & Kanwisher, N. Differential selectivity for dynamic versus static information in face-selective cortical regions. Neuroimage 56, 2356–2363 (2011).

Jokisch, D., Daum, I., Suchan, B. & Troje, N. Structural encoding and recognition of biological motion: Evidence from event-related potentials and source analysis. Behav. Brain Res. 157, 195–204 (2005).

Dasgupta, S., Tyler, S. C., Wicks, J., Srinivasan, R. & Grossman, E. D. Network connectivity of the right STS in three social perception localizers. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 29, 221–234 (2017).

Grosbras, M., Beaton, S. & Eickhoff, S. B. Brain regions involved in human movement perception: A quantitative voxel-based meta-analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 33, 431–454 (2012).

Saxe, R. & Wexler, A. Making sense of another mind: The role of the right temporo-parietal junction. Neuropsychologia 43, 1391–1399 (2005).

Yang, D.Y.-J., Rosenblau, G., Keifer, C. & Pelphrey, K. A. An integrative neural model of social perception, action observation, and theory of mind. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 51, 263–275 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a European Research Council Starting Grant (Grant number: THEMPO-758473 to L.P.) and by a PhD fellowship of the NSCo doctoral school of the University Claude Bernard Lyon 1 (to V.M). The authors are grateful to Emmanuelle Bellot for collecting the fMRI data, and to Céline Spriet for support in coding and data analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.M.: conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, data curation, writing—original draft. E.A.: conceptualization, methodology, software, writing—review and editing. P-A.B: methodology, review. L.P.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, resources, writing—original draft, funding acquisition, supervision. all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Munin, V., Abassi, E., Beuriat, PA. et al. The effects of spatial relations and motion information in social scene perception. Sci Rep 15, 25817 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07870-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-07870-1