Abstract

To determine the distribution of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness (RNFL) and its associated factors in a normal adult population using Spectralis spectral-domain (SD) optical coherence tomography (OCT). This research was conducted utilizing data from the third phase of the Shahroud Eye Cohort Study. Participants were selected from Shahroud City through a multi-stage cluster sampling technique. Uncorrected and best-corrected visual acuity, as well as refraction, were assessed for all participants. Subsequently, each individual underwent slit-lamp examinations conducted by an ophthalmologist. Following pupillary dilation with tropicamide 1% drops, fundoscopic examinations were carried out, and OCT imaging was performed using a Heidelberg Spectralis OCT device. A total of 3,700 eyes from 2,102 participants were included in this report. The average global RNFL thickness recorded in this study was 100.3 µm (95% CI: 99.9-100.7). When analyzed by sex, the average global RNFL thickness was 99.5 µm (95% CI: 98.9-100.1) for men and 100.9 µm (95% CI: 100.3-101.5) for women. Utilizing a multiple generalized estimating equations (GEE) model, the global RNFL thickness demonstrated a direct association with body mass index (β = 0.11; p = 0.013), corneal radius of curvature (β = 5.27; p < 0.001), and macular volume (β = 7.64; p < 0.001) while showing an inverse relationship with axial length (β=-2.29; p < 0.001), central macular thickness (β=-21.39; p = 0.002), and the presence of diabetes (β=-1.09; p = 0.009). The RNFL thickness profile within a normative cohort aged 50 to 74 years was demonstrated using Spectralis SD-OCT imaging. Beyond biometric indices, it is crucial to consider certain systemic factors that may influence RNFL thickness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide, accounting for an estimated 2.8–4.4% of all cases of blindness and 3.2–5.2% of moderate to severe visual impairment in individuals aged 50 years and older1. Projections indicate that the prevalence of glaucoma will increase from 76 million in 2020 to 111.8 million by 2040, primarily due to the global aging population2. This trend highlights the urgent need to address glaucoma as a major public health concern.

Glaucoma often develops asymptomatically during its early stages, characterized by the degeneration of retinal ganglion cells and changes in the optic nerve head1. Evaluating the peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) thickness is essential for diagnosing and managing patients with glaucoma and other optic nerve disorders. This is because RNFL damage is one of the earliest signs of glaucoma, occurring before any detectable alterations in visual fields. Studies suggest that up to 50% of retinal ganglion cells may be lost before visual field defects become apparent3. This parameter has aided in diagnosing neurodegenerative conditions and their association with depression4, as well as in diagnosing and monitoring the progression and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and multiple sclerosis5,6,7.

The RNFL thickness reference values are determined for each specific measurement device, and these values vary among different devices8. The importance of racial factors has led to research examining the variations in RNFL thickness among different racial groups9,10. Research indicates that RNFL thickness diminishes at an average rate of 0.36% annually, corresponding to a reduction of approximately 0.365 microns (µm)11. Although age-related variations in RNFL thickness have been documented, there is a notable scarcity of studies focusing specifically on middle-aged and older populations12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. A limited proportion of participants in previous studies were middle-aged or elderly13, and those studies concentrating solely on these age groups often involved small sample sizes21. This is while the prevalence of glaucoma and other optic nerve disorders tends to rise with age, with reported prevalence rates increasing from 0.9% among individuals aged 40–44 years to 3.55% for those aged 60–64 years22. This trend underscores the necessity of investigating RNFL thickness within this demographic.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a biomedical instrument that uses non-invasive low-coherence interferometry to generate quantitative cross-sectional images of the retina, optic nerve, and associated structures in vivo. This technology enables the early and objective differentiation between normal and glaucomatous eyes by evaluating RNFL thickness, a crucial parameter in OCT analysis23. The Heidelberg Spectralis device is a spectral-domain (SD) OCT system that operates at a speed 60 times greater and with an accuracy 5 times higher than that of time-domain (TD) OCT24,25. In our previous research, we documented changes in the RNFL thickness over five years within the same study cohort utilizing Cirrus HD-OCT26. Our primary objective is to evaluate the normal distribution of RNFL thickness in individuals aged 50 to 74 years, along with various associated factors, using the Heidelberg Spectralis system.

Materials and methods

This report is part of the third phase of the Shahroud Eye Cohort Study, conducted cross-sectionally in 2019. This particular phase targeted individuals aged 50 to 74 years. Detailed descriptions of the sampling methods and methodologies related to the first phase of the study have been presented in earlier publications27, with a concise summary provided in this section.

In this research, participants were obtained from Shahroud city (urban region) through a multi-stage stratified cluster sampling technique. A total of 300 clusters were identified within Shahroud, with each cluster comprising 20 individuals. Given that the primary health care system in Iran encompasses 9 health centers serving the Shahroud population, each health center was treated as a distinct stratum, and the number of clusters was allocated in accordance with the population distribution across these centers. The heads of the clusters for each center were systematically determined using the household file numbers maintained at the health centers. Following obtaining informed consent from each participant, demographic data, information regarding tobacco use, and medical and ophthalmological histories were collected. Subsequently, optometric and ophthalmological assessments, along with imaging procedures, were conducted for the participants.

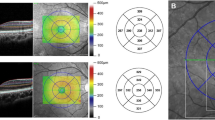

Optometric examinations included the measurement of both uncorrected and best-corrected visual acuities, non-cycloplegic refraction through autorefractometer and retinoscopy, as well as lensometry. Biometric data were collected using the Lenstar device, followed by a slit-lamp examination performed by an ophthalmologist for each participant. After administering tropicamide 1% drops for pupillary dilation, fundoscopic and ophthalmoscopic examinations were conducted for all individuals. Retinal imaging was subsequently performed in a dark room by a trained nurse utilizing the Heidelberg Spectralis OCT system (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). The RNFL optic disc protocol was employed to assess the RNFL thickness through a circular scan centered on the optic disc. This circular scan consists of 1536 A-scan points arranged in a 12-degree circle, which corresponds to a retinal diameter of 3.5–3.6 mm in eyes exhibiting normal corneal curvature. The device operates at an acquisition rate of 40,000 A-scans per second, achieving an axial resolution of approximately 3.9 mm and a lateral resolution of 6 mm. A real-time eye-tracking system is integrated to adjust for involuntary eye movements that may occur during imaging. Furthermore, automatic segmentation of the upper and lower borders of the RNFL is provided to compute the global RNFL thickness. The RNFL thickness values are also detailed in four distinct quadrants: superior, inferior, nasal, and temporal. The accompanying software generates a quality score (Q score) that reflects signal strength, ranging from 0 (indicating poor quality) to 40 (indicating excellent quality). A 20 × 20° macular volume scan was also applied to measure macular thickness and macular volume.

Definitions

Refractive errors were defined according to the spherical equivalent (SE) refraction. Myopia was identified as an SE of less than − 0.5 diopters (D), while hyperopia was characterized by an SE exceeding + 0.5 D28,29,30.

Exclusion criteria

In this report, the exclusion criteria were the inability to measure the RNFL thickness or any missing data in its sections, a history of retinal surgeries or diseases, previous glaucoma surgeries or glaucoma conditions, any ocular surgeries other than cataract procedures, best-corrected visual acuity worse than 20/25, myopia exceeding − 6.00 D, OCT scans exhibiting artifacts (motion artifacts, inadequate segmentation, signal loss, and a quality score below 15), as well as data classified as outliers (those deviating more than three standard deviations from the mean).

Statistical analysis

The average values and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the global RNFL thickness and RNFL thickness measurements across different sectors, were recorded for all participants and categorized by study variables. The cluster sampling method was considered in calculating the standard error. Furthermore, the 1% and 5% percentiles were included to depict the distribution of the global and sectoral RNFL thicknesses. To evaluate normality, the skewness and kurtosis of the global RNFL thickness were computed, and the normal range was calculated as the mean ± 2 standard deviations.

Since data from both eyes were included in the analysis, statistical models were applied to examine the relationships between variations in RNFL thickness and other influencing factors. Simple and multiple generalized estimating equations (GEE) models were employed to analyze these associations. The final multiple GEE model was developed using the backward method, with coefficients reported alongside their respective 95% CIs.

Ethical considerations

The Shahroud Eye Cohort Study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences (ethics code: IR.SHMU.REC. 1398.039). All methods were carried out in accordance with the Helsinki tenets and other relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Among the 4,394 individuals involved in this research, 5266 eyes from 2648 participants underwent retinal imaging using Heidelberg Spectralis OCT.

A total of 1,566 eyes were excluded from the analysis for various reasons. Specifically, 188 eyes were omitted due to the lack of RNFL thickness measurements or incomplete data. Additionally, 173 eyes were excluded because of retinal diseases and/or related surgical procedures. Furthermore, 357 eyes were removed from the analysis due to glaucoma and its associated surgical treatments. Moreover, 482 eyes were excluded as their best-corrected visual acuity was worse than 20/25. Fifteen eyes were omitted for having myopia exceeding − 6.00 D, while 74 eyes were excluded due to a prior history of ocular surgery. Lastly, 150 eyes were removed because their signal quality was below 15, and 127 eyes were classified as outliers. Ultimately, 3,700 eyes from 2,102 participants were analyzed in this report.

Notably, 56% (1,178) of the participants were female. The average age of the individuals analyzed was 60.4 ± 5.96 years (range: 50 to 74 years). The mean SE for the examined eyes was 0.19 ± 1.25 D (range: -5.75 to 5.88 D). Table 1 shows the distribution of demographic characteristics, medical history, and ocular indices of the participants in this study.

Table 2 presents the mean values and 95% CIs for the global and sectoral RNFL thicknesses, categorized by age and sex and among all study participants. The findings indicate that the average global RNFL thickness in this study was 100.3 µm (95% CI: 99.9-100.7). Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of the global RNFL thickness among the study participants.

The skewness and kurtosis values for the global RNFL thickness in this study were − 0.85 and 0.014, respectively. The average global RNFL thickness for male participants was 99.5 µm (95% CI: 98.9-100.1), while female participants exhibited an average thickness of 100.9 µm (95% CI: 100.3-101.5). As shown in Table 2, the changes in global RNFL thickness did not follow a linear pattern concerning age, with the lowest values observed in individuals aged 70 to 74 years.

Additionally, Fig. 2 illustrates a significant interaction between age and sex concerning the average overall RNFL thickness, revealing an increase in thickness for women and a decrease for men as age progresses.

The normal ranges for RNFL thickness values in the examined population were categorized by age and sex, employing the mean and two SD as benchmarks (Table 3). The global RNFL thickness is determined to fall within the normal range of 81.26 to 119.32 µm.

Table 4 illustrates the 1st and 5th percentiles for both global RNFL thickness and RNFL thickness across different sectors. In this cohort, the 1st and 5th percentiles for global RNFL thickness were noted at 77.01 and 85 µm, respectively. The temporal-inferior sector demonstrated the highest RNFL thickness at 144.8 µm, whereas the temporal sector recorded the lowest thickness at 69.5 µm. A repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed a statistically significant difference in RNFL thickness among the various sectors (p < 0.001).

The average of global RNFL thickness in emmetropic, myopic, and hyperopic individuals was recorded as 100 μm (95% CI: 99.4-100.5), 98.3 µm (95% CI: 97.4–99.1), and 101.9 µm (95% CI: 101.2-102.5), respectively. Notably, myopes exhibited a significantly reduced global RNFL thickness. As illustrated in Fig. 3, the average RNFL thickness varies with the severity of refractive errors, revealing that individuals with high myopia and high hyperopia exhibited the thinnest RNFL measurements.

The association between global RNFL thickness and the examined variables was analyzed using simple and multiple GEE models, with the findings presented in Table 5. The multiple GEE model revealed a statistically significant interaction between age and sex in relation to global RNFL thickness. Specifically, women aged 70 to 74 years exhibited a greater global RNFL thickness [β = 3.15 (95% CI: 0.00; 6.29); p = 0.050] when compared to their male counterparts within the same age group. Furthermore, this model indicated that global RNFL thickness is significantly directly associated with body mass index [β = 0.11 (95%CI: 0.02; 0.19); p = 0.013], corneal radius of curvature [β = 5.27 (95%CI: 3.58; 6.96); p < 0.001], and macular volume [β = 8.30 (95%CI: 7.47; 9.13); p < 0.001)], while exhibiting a significant inverse relationship with axial length [β=-2.29 (95%CI: -2.84; -1.74); p < 0.001)] and central macular thickness [β=-21.39 (95%CI: -35.05; -7.73); p = 0.002)]. Moreover, the analysis indicated that global RNFL thickness was significantly lower in individuals with diabetes compared to those without the condition [β=-1.09 (95%CI: -1.91; -0.27); p = 0.009)].

Discussion

This study investigated the distribution of RNFL thickness and its associated factors in a normal population aged 50 to 74 years, employing the Spectralis SD-OCT device. As previously noted, changes in RNFL thickness over a five-year period have already been documented in a different sample from this cohort using the Cirrus device26. The current study specifically focuses on the RNFL thickness distribution within the 50 to 74 age range, thereby providing significant contributions to existing databases.

The results of this study show that the average global RNFL thickness was 100.3 µm, with a range of 99.9 to 100.7 µm. A summary of findings from previous studies is provided in Table 6. Specifically, the influence of race and genetic factors should not be overlooked, as prior research has indicated that RNFL thickness measurements and various ocular parameters exhibit significant differences among racial groups9,52.

The literature reveals a significant variability in the mean RNFL thickness, with reported values ranging from 87.3 to 126.98 μm. This inconsistency can largely be attributed to several factors, notably the type of OCT device used. Additionally, variations in age distribution among study populations likely contribute to these discrepancies, as RNFL thickness is known to decrease with age. In comparison to East and South Asian populations, the average RNFL thickness in the Iranian cohort is lower, measuring around 92.47 ± 8.56 μm, although some studies report values as high as 98.6 μm depending on age and methodology. In contrast, African American populations demonstrate higher RNFL thickness, with averages reaching up to 101.5 μm. These findings underscore the necessity for population-specific normative data in the cross-ethnic screening of glaucoma and other optic neuropathies, as neglecting ethnic differences may result in misdiagnosis or inadequate clinical management. Furthermore, the variability in measurement techniques across different studies may also play a role in the observed differences.

In the present study, the RNFL thickness was observed to be greatest in the inferior sector, measuring 129.75 μm, followed by the superior sector at 126.05 μm, the nasal sector at 75.9 μm, and the temporal sector at 69.5 μm. These findings align with previous research conducted on younger populations and can be explained by the “Inferior-Superior-Nasal-Temporal” rule, suggesting a “double-humped” configuration53,54.

Age is recognized as a significant factor affecting RNFL thickness. Prior research has established an inverse correlation between age and RNFL thickness, indicating an annual reduction ranging from 0.15 to 0.63 μm55,56,57. Nevertheless, several studies failed to demonstrate a relationship between age and RNFL thickness, potentially attributable to the younger age of their participants58,59. Notably, the most pronounced loss of nerve fibers occurs after the age of 50 years, as evidenced by histological investigations conducted by Quigley et al.60, which reveal that individuals over 50 years of age experience a threefold increase in the loss of optic nerve axons compared to their younger counterparts. The decline in RNFL thickness associated with aging may be linked to a reduction in venous caliber, leading to cytotoxic and vasogenic edema, which ultimately results in arteriolar stenosis21. In the present study, we found a significant interaction between age and sex concerning the RNFL thickness. Specifically, RNFL thickness increased with age in females, whereas it decreased in males, with women exhibiting a higher global RNFL thickness. The research conducted by Wanger et al. highlighted distinct RNFL profiles between genders61. While numerous studies have indicated that women typically have a thicker RNFL49, Hashemi et al. reported findings suggesting that women may have a thinner RNFL in their analysis10. Additionally, several investigations did not find a significant relationship between sex and RNFL thickness57. Alpogan et al. observed that, after controlling for age, a later onset of menopause correlated with increased RNFL thickness62. Moreover, Jeong et al. noted that the decline in RNFL thickness with age was less marked in women63. These findings are consistent with our results, which demonstrate a significant interaction between age and sex concerning RNFL thickness—an area that has not been extensively examined in existing literature. Our findings indicate that RNFL thickness generally increases with age in women, whereas it tends to decrease in men. In contrast, research conducted by Rougier et al. revealed that women aged 80 years and older exhibited lower RNFL thickness compared to their younger counterparts under 80 years64.

In the present study, an indirect association was observed between axial length and the RNFL thickness, which is consistent with previous research findings65. Specifically, various studies have demonstrated that for each millimeter increase in axial length, the average RNFL thickness decreases by approximately 2.2 to 3.6 μm13. Lamparter et al. identified an independent relationship between myopia and axial length with RNFL thickness; however, the potential impact of the magnification effect on this association remained unclear66. Vernon et al. reported no significant correlation between age, refractive errors, and axial length, a finding that may be influenced by the small sample size and limited age range of the participants67. The significant correlation between axial length and RNFL thickness suggests that axial length should be included as a measurable variable in normative databases. This inclusion could enhance the accuracy and relevance of assessments related to ocular health68.

The present study corroborates the findings of Choi et al., revealing a significant association between myopia and a reduction in RNFL thickness69. Research by Zhao et al. has established that retinal elongation plays a role in the observed decrease in RNFL thickness70. Additionally, Grudzinska et al. have identified that diminished retrobulbar blood flow in individuals with myopia contributes to reduction in RNFL thickness71. The magnification effect associated with OCT scans results in larger projection rings on the retina in eyes with elongated axial lengths, which in turn leads to a decrease in RNFL thickness as the distance from the optic disc increases21,72. Hwang et al. have shown that when this magnification effect is taken into consideration, the relationship between myopia and RNFL thickness loses its statistical significance73. Importantly, higher levels of myopia are linked to a thinner RNFL in the superior, nasal, and inferior regions, whereas the temporal region tends to exhibit a thicker RNFL74,75. The mechanical stretching and thinning of the RNFL due to increased axial length in myopia is especially evident, except for the temporal sector76. The relative consistency of the temporal quadrant in response to varying degrees of myopia may be due to its naturally thinner structure and the limited direct influence of myopia on this area, or it may result from the retina being dragged toward the temporal side. In the study conducted by Hoh et al.77. , no significant correlation was found between RNFL thickness and myopia or axial length77. Furthermore, Hoh et al.77. indicated that varying degrees of myopia and axial length did not influence RNFL thickness when a 4.5 mm scan diameter was used. Conversely, Alsail et al. reported that for each diopter increase in refractive error towards hyperopia, there was an average increase of 1.4 μm in RNFL thickness57. Consistent with the present study, studies by Yasir et al. and Wu et al. demonstrated that greater severity of myopia was linked to a notable reduction in RNFL thickness78,79. Additionally, Lee et al. observed that the decline in RNFL thickness among the elderly occurred more rapidly in individuals with high myopia compared to those in the control group56. Consequently, particularly at elevated levels of myopia, it is crucial to consider differential diagnoses for reduced RNFL thickness to avoid misdiagnosis with open-angle glaucoma, which is more prevalent among myopic individuals80. Utilizing normative databases while accounting for myopia significantly mitigates the discrepancies in RNFL thickness observed among individuals with varying degrees of myopia81.

In the present study, a direct relationship was observed between the corneal radius of curvature and RNFL thickness. Previous research has explored the association between corneal parameters and RNFL thickness. For instance, Liu et al. reported that eyes with higher levels of corneal astigmatism demonstrated reduced RNFL thickness in the temporal sector, a finding attributed to variations in OCT reflectivity and backscattering82. It has been shown that corneas with steeper keratometric values tend to exhibit thinner central corneal thickness83. The study conducted by Arranz-Marquez et al. indicated a direct relationship between RNFL thickness and central corneal thickness84. Moreover, findings from Wang et al. suggested that a flatter anterior corneal curvature was linked to increased RNFL thickness33.

The present study observed a significant direct association between the RNFL thickness and body mass index. Prior investigations have suggested that a higher BMI may confer a protective effect against glaucoma85,86. For example, research conducted by Leske et al. indicated that an elevated BMI is linked to a decreased risk of developing open-angle glaucoma, suggesting potential shared genetic factors87. However, the nature of this association appears to differ among various studies. For instance, Khawaja et al. reported an inverse correlation between RNFL thickness and body mass index, however, this finding was limited to male participants, presenting a contrast to our findings that could be influenced by racial differences88. Furthermore, some studies did not find a significant link between RNFL thickness and body mass index; notably, the study performed by Lamparter et al.66 did not utilize multiple regression analysis, while the study conducted by Cheung et al.89 had a small sample size.

In the current investigation, an inverse correlation was observed between the central macular thickness and the RNFL thickness. This association may be linked to the aging process, as indicated by the findings of Chua et al., who noted that RNFL thickness at the fovea, along with the inner and outer segments of photoreceptors, tend to increase with age due to the activity and thickening of Müller glial cells90. The research conducted by Chauhan et al. reported no significant changes in RNFL thickness within the macula as individuals age91. Furthermore, the present study revealed a direct relationship between RNFL thickness and macular volume. Ojima et al. documented a similar direct correlation in the early stages of glaucoma, where both macular volume and RNFL thickness were found to be diminished92. Additionally, the work of Lederer et al. highlighted that as glaucoma progresses, there is an escalation in ganglion cell death, leading to a reduction in macular cellularity and, consequently, a decrease in macular volume93.

In alignment with the present study, the research conducted by Ezhilvendhan et al. demonstrated a significant association between diabetes and a reduction in RNFL thickness94. Diabetes induces apoptosis in ganglion and Müller cells, leading to a decrease in RNFL thickness before the onset of diabetic retinopathy95. The neurodegenerative processes associated with diabetes are attributed to ischemic conditions and metabolic interactions that precede vascular alterations96. Furthermore, RNFL thickness may serve as a predictive marker for the onset of diabetes97. The duration of diabetes plays a critical role; for instance, the findings of Lee et al. indicated that patients with a diabetes duration exceeding ten years exhibited markedly lower RNFL thickness compared to those with a shorter duration of the disease98. Conversely, the study by Demir et al. did not identify a significant relationship between type 2 diabetes and RNFL thickness, although it is important to note that their sample size was relatively limited99.

This study acknowledges certain limitations that warrant attention. Due to the cross-sectional design, causal relationships between variables such as myopia, age, and other factors cannot be definitively established. Furthermore, the findings are specific to the Iranian population, and caution is advised when attempting to generalize these results to other groups, particularly patient populations. One significant limitation of this study is the potential amplification effect arising from variations in axial length, which could affect the measurements of RNFL thickness, particularly in myopic eyes. To address this issue, future investigations should incorporate axial length-based correction techniques to reduce bias and improve the comparability of results across diverse populations. Nonetheless, a notable strength of this research lies in examining the RNFL thickness within a substantial sample of the normal population, utilizing a random sampling approach for individuals aged 50 years and older.

In conclusion, applying standard databases, while taking into account a range of variables, proves to be more effective for the early diagnosis of glaucoma compared to traditional methods that rely exclusively on age. This underscores the significance of incorporating demographic, ocular, and systemic factors that influence RNFL thickness.

Data availability

Data are available from corresponding author (afotouhi@tums.ac.ir) on reasonable request..

References

Steinmetz, J. D. et al. Causes of blindness and vision impairment in 2020 and trends over 30 years, and prevalence of avoidable blindness in relation to VISION 2020: the right to sight: an analysis for the global burden of disease study. Lancet Global Health. 9(2), e144–e160 (2021).

Tham, Y-C. et al. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology 121(11), 2081–2090 (2014).

Vazquez, L. E., Bye, A. & Aref, A. A. Recent developments in the use of optical coherence tomography for glaucoma. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 32(2), 98–104 (2021).

van der Heide, F. C. T. et al. Association of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness, an index of neurodegeneration, with depressive symptoms over time. JAMA Netw. Open. 4(11), e2134753 (2021).

Mathew, S. et al. Association of brain volume and retinal thickness in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 91(2), 743–752 (2023).

Sánchez, D. et al. Usefulness of peripapillary nerve fiber layer thickness assessed by optical coherence tomography as a biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 16345 (2018).

Abalo-Lojo, J. M., Treus, A., Arias, M., Gomez-Ulla, F. & Gonzalez, F. Longitudinal study of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness changes in a multiple sclerosis patients cohort: A long term 5 year follow-up. Mult Scler. Relat. Disord. 19, 124–128 (2018).

Savini, G., Carbonelli, M. & Barboni, P. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measurement by Fourier-domain optical coherence tomography: a comparison between cirrus-HD OCT and RTVue in healthy eyes. J. Glaucoma. 19(6), 369–372 (2010).

Nousome, D. et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in healthy eyes of black, chinese, and Latino americans: a population-based multiethnic study. Ophthalmology 128(7), 1005–1015 (2021).

Hashemi, H. et al. Retinal nerve fibre layer thickness in a general population in Iran. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 45(3), 261–269 (2017).

Celebi, A. R. & Mirza, G. E. Age-related change in retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured with spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54(13), 8095–8103 (2013).

Rafati, S., Khabazkhoob, M., Mortazavi, M. & Asharlous, A. Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and its ocular and systemic determinants in an elderly population: A population-based study. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 35(2), 135–144 (2023).

Budenz, D. L. et al. Determinants of normal retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured by stratus OCT. Ophthalmology 114(6), 1046–1052 (2007).

Sung, K. R., Kim, D. Y., Park, S. B. & Kook, M. S. Comparison of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured by cirrus HD and stratus optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology 116(7), 1264–1270 (2009). 1270 e1261.

Xie, X. et al. Determinants of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer’s grayscale value in normal eyes by spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 9577 (2021).

Manassakorn, A., Chaidaroon, W., Ausayakhun, S., Aupapong, S. & Wattananikorn, S. Normative database of retinal nerve fiber layer and macular retinal thickness in a Thai population. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 52(6), 450–456 (2008).

Mansoori, T., Viswanath, K. & Balakrishna, N. Quantification of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness using spectral domain optical coherence tomography in normal Indian population. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 60(6), 555–558 (2012).

Kanamori, A. et al. Evaluation of the effect of aging on retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured by optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmologica 217(4), 273–278 (2003).

Rougier, M. B. et al. Retinal nerve fibre layer thickness measured with SD-OCT in a population-based study of French elderly subjects: the alienor study. Acta Ophthalmol. 93(6), 539–545 (2015).

Chen, C-Y. et al. The relationship between age, axial length and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in the normal elderly population in taiwan: the Chiayi eye study in Taiwan. PLoS One. 13(3), e0194116 (2018).

Arnould, L. et al. Diagnostic ability of spectral-domain optical coherence tomography peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness to discriminate glaucoma patients from controls in an elderly population (The MONTRACHET study). Acta Ophthalmol. 98(8), e1009–e1016 (2020).

Hashemi, H. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of glaucoma in an adult population from Shahroud, Iran. J. Curr. Ophthalmol. 31(4), 366–372 (2019).

Qin, J. & An, L. Optical coherence tomography for ophthalmology imaging. In Optical Imaging in Human Disease and Biological Research, 197–216. (Springer, 2021).

Thomas, B. J. et al. Ultra high-resolution anterior segment optical coherence tomography in the diagnosis and management of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Ocul Surf. 12(1), 46–58 (2014).

Liu, M. M. et al. Comparison of time- and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in management of diabetic macular edema. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 55(3), 1370–1377 (2014).

Hashemi, H., Khabazkhoob, M., Heydarian, S., Emamian, M. H. & Fotouhi, A. Five-year changes in retinal nerve fibre layer thickness in the adult population: a population-based cohort study. Clin Exp. Optom. 1–9 (2024).

Fotouhi, A. et al. Cohort profile: shahroud eye cohort study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 42(5), 1300–1308 (2013).

Hashemi, A., Khabazkhoob, M. & Hashemi, H. High prevalence of refractive errors in an elderly population; a public health issue. BMC Ophthalmol. 23(1), 38 (2023).

Mashige, K. P. et al. Prevalence of refractive errors in the INK area, Durban, South Africa. Optom. Vis. Sci. 93(3), 243–250 (2016).

Pan, C. W. et al. Prevalence of refractive errors in a multiethnic Asian population: the Singapore epidemiology of eye disease study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54(4), 2590–2598 (2013).

Kampougeris, G., Spyropoulos, D., Mitropoulou, A., Zografou, A. & Kosmides, P. Peripapillary retinal nerve fibre layer thickness measurement with SD-OCT in normal and glaucomatous eyes: distribution and correlation with age. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 6(5), 662–665 (2013).

Zhao, L., Wang, Y., Chen, C. X., Xu, L. & Jonas, J. B. Retinal nerve fibre layer thickness measured by Spectralis spectral-domain optical coherence tomography: the Beijing Eye Study. Acta Ophthalmol. 92(1), e35–e41 (2014).

Wang, Y. X. et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness. The Beijing Eye Study 2011. PLoS One. 8(6), e66763 (2013).

Malik, A., Singh, M., Arya, S. K., Sood, S. & Ichhpujani, P. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in Indian eyes with optical coherence tomography. Nepal. J. Ophthalmol. 4(1), 59–63 (2012).

Kanno, M., Nagasawa, M., Suzuki, M. & Yamashita, H. Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in normal Japanese eyes measured with optical coherence tomography. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 54(1), 36–42 (2010).

Peng, P. H. & Lin, H. S. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured by optical coherence tomography in non-glaucomatous Taiwanese. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 107(8), 627–634 (2008).

Gyatsho, J., Kaushik, S., Gupta, A., Pandav, S. S. & Ram, J. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in normal, ocular hypertensive, and glaucomatous Indian eyes: an optical coherence tomography study. J. Glaucoma. 17(2), 122–127 (2008).

Qu, S., Sun, X. T., Xu, W. & Rong, A. Analysis of peripapilary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness of healthy Chinese from Northwestern Shanghai using cirrus HD-OCT. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 7(4), 654–658 (2014).

Thapa, M., Khanal, S., Shrestha, G. B. & Sharma, A. K. Retinal nerve fibre layer thickness in a healthy Nepalese population by spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Nepal. J. Ophthalmol. 6(2), 131–139 (2014).

Gupta, P. et al. Relationship between peripapillary choroid and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in a population-based sample of nonglaucomatous eyes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 161, 4–11 (2016). e12.

Chansangpetch, S. et al. Differences in optic nerve head, retinal nerve fiber layer, and ganglion cell complex parameters between Caucasian and Chinese subjects. J. Glaucoma. 27(4), 350–356 (2018).

Jang, J. W., Lee, M. W. & Cho, K. J. Comparative analysis of mean retinal thickness measured using SD-OCT in normal young or old age and glaucomatous eyes. Int. Ophthalmol. 38(6), 2417–2426 (2018).

Saha, M., Bandyopadhyay, S., Das, D. & Ghosh, S. Comparative analysis of macular and peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in normal, glaucoma suspect and glaucomatous eyes by optical coherence tomography. Nepal. J. Ophthalmol. 8(16), 110–118 (2016).

Schweitzer, C. et al. Diagnostic performance of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness for detection of glaucoma in an elderly population: the ALIENOR study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 57(14), 5882–5891 (2016).

Park, K-A., Choi, D. D. & Oh, S. Y. Macular choroidal thickness and peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in normal adults and patients with optic atrophy due to acute idiopathic demyelinating optic neuritis. Plos One. 13(6), e0198340 (2018).

Hoffmann, E. M. et al. The distribution of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and associations with age, refraction, and axial length: the Gutenberg health study. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 256(9), 1685–1693 (2018).

Perez, C. I. et al. Normative database and color-code agreement of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer and macular ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer thickness in a Vietnamese population. J. Glaucoma. 27(8), 665–673 (2018).

Ho, H. et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in a multiethnic normal Asian population: the Singapore epidemiology of eye diseases study. Ophthalmology 126(5), 702–711 (2019).

Mehboob, M. A., Amin, Z. A. & Islam, Q. U. Comparison of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness between normal population and patients with diabetes mellitus using optical coherence tomography. Pakistan J. Med. Sci. 35(1), 29 (2019).

Ocansey, S. et al. Normative values of retinal nerve fibre layer thickness and optic nerve head parameters and their association with visual function in an African population. J. Ophthalmol. 2020(1), 7150673 (2020).

Wu, J. et al. Retinal nerve fibre layer thickness measured with SD-OCT in a population-based study: the Handan eye study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 107(8), 1156–1164 (2023).

Beniz, L. A. F. et al. Impact of race and ethnicity on glaucoma progression detection by perimetry and optical coherence tomography. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 30752 (2024).

Shin, J. W., Uhm, K. B., Seong, M. & Lee, D. E. Retinal nerve fiber layer volume measurements in healthy subjects using spectral domain optical coherence tomography. J. Glaucoma. 23(8), 567–573 (2014).

Chen, B., Chen, S., Yang, J., Wang, H. & Zhang, M. Assessment of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer optical density ratios in healthy eyes using optical coherence tomography with different analytical radii. Curr. Eye Res. 49(4), 417–424 (2024).

Sung, K. R. et al. Effects of age on optical coherence tomography measurements of healthy retinal nerve fiber layer, macula, and optic nerve head. Ophthalmology 116(6), 1119–1124 (2009).

Lee, M. W., Kim, J. M., Shin, Y. I., Jo, Y. J. & Kim, J. Y. Longitudinal changes in peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in high myopia: A prospective, observational study. Ophthalmology 126(4), 522–528 (2019).

Alasil, T. et al. Analysis of normal retinal nerve fiber layer thickness by age, sex, and race using spectral domain optical coherence tomography. J. Glaucoma. 22(7), 532–541 (2013).

Xu, J. et al. Retinal nerve fibre layer thickness and macular thickness in patients with esotropic amblyopia. Clin. Exp. Optom. 96(3), 267–271 (2013).

Dhami, A., Dhasmana, R. & Nagpal, R. C. Correlation of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and axial length on fourier domain optical coherence tomography. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 10(4), NC15–NC17 (2016).

Quigley, H. A., Dunkelberger, G. R. & Green, W. R. Retinal ganglion cell atrophy correlated with automated perimetry in human eyes with glaucoma. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 107(5), 453–464 (1989).

Wagner, F. M. et al. Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer profile in relation to refractive error and axial length: results from the Gutenberg health study. Transl Vis. Sci. Technol. 9(9), 35 (2020).

Alpogan, O. & Tekcan, H. Effects of menopause on the retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell complex and on intraocular pressure. Menopause 29(4), 460–464 (2022).

Jeong, D., Sung, K. R., Jo, Y. H. & Yun, S. C. Age-Related physiologic thinning rate of the retinal nerve fiber layer in different levels of myopia. J. Ophthalmol. 2020(1), 1873581 (2020).

Rougier, M. B. et al. Retinal nerve fibre layer thickness measured with SD-OCT in a population‐based study of French elderly subjects: the A lienor study. Acta Ophthalmol. 93(6), 539–545 (2015).

Ganekal, S., Sadhwini, M. H. & Kagathur, S. Effect of myopia and optic disc area on ganglion cell-inner plexiform layer and retinal nerve fiber layer thickness. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 69(7), 1820–1824 (2021).

Lamparter, J. et al. Association of ocular, cardiovascular, morphometric and lifestyle parameters with retinal nerve fibre layer thickness. PLoS One. 13(5), e0197682 (2018).

Vernon, S. A., Rotchford, A. P., Negi, A., Ryatt, S. & Tattersal, C. Peripapillary retinal nerve fibre layer thickness in highly myopic Caucasians as measured by stratus optical coherence tomography. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 92(8), 1076–1080 (2008).

Aykut, V., Oner, V., Tas, M., Iscan, Y. & Agachan, A. Influence of axial length on peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in children: a study by RTVue spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Curr. Eye Res. 38(12), 1241–1247 (2013).

Choi, S. W. & Lee, S. J. Thickness changes in the fovea and peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer depend on the degree of myopia. Korean J. Ophthalmol. 20(4), 215–219 (2006).

Zhao, J. J., Zhuang, W. J., Yang, X. Q., Li, S. S. & Xiang, W. Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness distribution in Chinese with myopia measured by 3D-optical coherence tomography. Int. J. Ophthalmol. 6(5), 626–631 (2013).

Grudzińska, E. M., Zaborski, D. & Modrzejewska, M. Correlation between retrobulbar blood flow parameters and retinal nerve fiber, ganglion cell and inner plexus layer thickness in myopia. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 32(1), 643–650 (2022).

Jonas, J. B. Optic disk size correlated with refractive error. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 139(2), 346–348 (2005).

Hwang, Y. H. & Kim, Y. Y. Correlation between optic nerve head parameters and retinal nerve fibre layer thickness measured by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in myopic eyes. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 40(7), 713–720 (2012).

Kang, S. H., Hong, S. W., Im, S. K., Lee, S. H. & Ahn, M. D. Effect of myopia on the thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer measured by cirrus HD optical coherence tomography. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 51(8), 4075–4083 (2010).

Hwang, Y. H., Yoo, C. & Kim, Y. Y. Myopic optic disc tilt and the characteristics of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness measured by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. J. Glaucoma. 21(4), 260–265 (2012).

Leung, C. K. et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer measurements in myopia: an optical coherence tomography study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47(12), 5171–5176 (2006).

Hoh, S. T. et al. Peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness variations with myopia. Ophthalmology 113(5), 773–777 (2006).

Yasir, Z. H., Mittal, J. & Singh, A. K. Nomogram of peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in myopic eyes of North Indian population. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 70(2), 458–464 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Effect of refractive status on retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in Chinese population. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 261(1), 201–211 (2023).

Malakar, M. et al. Optical coherence tomography assisted retinal nerve fibre layer thickness profile in high myopia. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 9(2), NC01–03 (2015).

Yilmaz, H. et al. A myopic normative database for retinal nerve fiber layer thickness using optical coherence tomography. J. Glaucoma. 31(10), 816–825 (2022).

Liu, L., Zou, J., Huang, H., Yang, J. G. & Chen, S. R. The influence of corneal astigmatism on retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and optic nerve head parameter measurements by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Diagn. Pathol. 7, 55 (2012).

Krishnan, V. M., Jayalatha, K. & Vijayakumar, C. Correlation of central corneal thickness and keratometry with refraction and axial length: a prospective analytic study. Cureus 11(1). (2019).

Arranz-Marquez, E., Lauzirika, G., Teus, M. A. & Katsanos, A. Thinner retinal nerve fibre layer in healthy myopic eyes with thinner central corneal thickness. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 258(11), 2477–2481 (2020).

Ramdas, W. D. et al. Lifestyle and risk of developing open-angle glaucoma: the Rotterdam study. Arch. Ophthalmol. 129(6), 767–772 (2011).

Pasquale, L. R., Willett, W. C., Rosner, B. A. & Kang, J. H. Anthropometric measures and their relation to incident primary open-angle glaucoma. Ophthalmology 117(8), 1521–1529 (2010).

Leske, M. C., Connell, A. M., Wu, S. Y., Hyman, L. G. & Schachat, A. P. Risk factors for open-angle glaucoma. The Barbados eye study. Arch. Ophthalmol. 113(7), 918–924 (1995).

Khawaja, A. P. et al. Associations with retinal nerve fiber layer measures in the EPIC-Norfolk eye study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54(7), 5028–5034 (2013).

Cheung, C. Y. et al. Determinants of quantitative optic nerve measurements using spectral domain optical coherence tomography in a population-based sample of non-glaucomatous subjects. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 52(13), 9629–9635 (2011).

Chua, J. et al. Age-related changes of individual macular retinal layers among Asians. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 20352 (2019).

Chauhan, B. C. et al. Differential effects of aging in the macular retinal layers, neuroretinal rim, and peripapillary retinal nerve Fiber layer. Ophthalmology 127(2), 177–185 (2020).

Ojima, T. et al. Measurement of retinal nerve fiber layer thickness and macular volume for glaucoma detection using optical coherence tomography. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 51(3), 197–203 (2007).

Lederer, D. E. et al. Analysis of macular volume in normal and glaucomatous eyes using optical coherence tomography. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 135(6), 838–843 (2003).

Ezhilvendhan, K., Shenoy, A., Rajeshkannan, R., Balachandrachari, S. & Sathiyamoorthy, A. Evaluation of macular thickness, retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell layer thickness in patients among type 2 diabetes mellitus using optical coherence tomography. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 13(Suppl 2), S1055–S1061 (2021).

Fahmy, R. M., Bhat, R. S., Al-Mutairi, M., Aljaser, F. S. & El-Ansary, A. Correlation between glycemic control and peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in Saudi type II diabetics. Clin. Ophthalmol. 419–425 (2018).

Pinilla, I. et al. Changes in total and inner retinal thicknesses in type 1 diabetes with no retinopathy after 8 years of follow-up. Retina 40(7), 1379–1386 (2020).

Gong, X. et al. Associations between peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer and choroidal thickness with the development and progression of diabetic retinopathy. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 63(2), 7–7 (2022).

Lee, M-W. et al. Effects of prolonged type 2 diabetes on changes in peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in diabetic eyes without clinical diabetic retinopathy. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 6813 (2021).

Demir, M., Oba, E., Sensoz, H. & Ozdal, E. Retinal nerve fiber layer and ganglion cell complex thickness in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 62(6), 719–720 (2014).

Funding

This project is funded in part by the Noor Ophthalmology Research Center and Shahroud University of Medical Sciences (Project numbers: 8737 and 9826).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Design and conduct of the study (HH, AF); collection, management of the data (AF, ME); analysis, and interpretation of the data (HH, MK, AR, ME); and preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript (HH, MK, AR, ME, AF)..

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Shahroud Eye Cohort Study was approved by the ethics committee of Shahroud University of Medical Sciences (Reference numbers: IR.SHMU.REC. 1398.039). All methods were carried out in accordance with the Helsinki tenets and other relevant guidelines and regulations. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants..

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hashemi, H., Khabazkhoob, M., Riazifar, A. et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer thickness profile in an Iranian adult population. Sci Rep 15, 22349 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08011-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08011-4