Abstract

Patients on hemodialysis often experience intradialytic hypotension (IDH), contributing to increased cardiovascular disease and mortality. Midodrine, an α-1 adrenergic receptor agonist, is commonly prescribed for IDH treatment or prevention. However, the effects of midodrine on clinical outcomes remain unclear. We aimed to evaluate the impact of midodrine use on clinical outcomes in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. This retrospective study evaluated patients according to midodrine prescriptions based on a dataset from the hemodialysis quality assessment program and Health Insurance Review and Assessment. Propensity score matching was employed to minimize bias in baseline characteristics. The Cox regression model was used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) and confidence interval (CI) for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events (CVEs). Approximately 9.6% of 71,540 patients were prescribed midodrine. The numbers of patients in the No-proscription and Midodrine groups were 20,305 and 6,887 after matching, respectively. The 5-year patient survival rates in the No-prescription and Midodrine groups were 62.6% and 58.0%, respectively (P < 0.001). Midodrine use was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality (adjusted HR: 1.17, 95% CI 1.13–1.22, P < 0.001). A high dose of midodrine was associated with a higher HR for mortality than that in a No-prescription or low dose of midodrine. The risk of CVE between the groups was not significantly different. This study showed that midodrine use was associated with a dose-dependent increase in all-cause mortality. Clinicians should actively search for and treat comorbidities and risk factors for IDH in patients requiring midodrine, especially frequent dosing. The findings should be interpreted with caution due to the observational nature of the study and should be validated in future prospective studies incorporating comprehensive IDH data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hemodialysis (HD) is one of the most widely used renal replacement therapies worldwide. Patients undergoing HD are prone to a shortening of life expectancy compared to the general population, particularly regarding cardiovascular diseases1,2. These individuals exhibit an elevated risk of hypertension and are more frequently prescribed medications to manage it than that in patients not undergoing HD3. Additionally, it is well established that hypertension in patients undergoing HD contributes to increased mortality and morbidity rates. However, the risk of hypotension is significant. The risk of intradialytic hypotension (IDH), frequently occurring during HD, is well-documented and is known to significantly impact the high mortality rates observed in patients undergoing HD4. Hypotension in these patients arises from impaired compensatory mechanisms, including sympathetic tone, plasma refilling, and venous pooling limits5,6.

Midodrine, a prodrug converted into desglymidodrine (an α-1 adrenergic receptor agonist), is as a vasoconstrictor that increases systemic vascular resistance and elevates blood pressure7. Additionally, it is considered one of the medical treatments for hypotension. Midodrine is commonly prescribed for hypotension during or after HD sessions, and previous studies following its prescription have shown positive results in increasing blood pressure8. However, most of these studies lacked sufficient data on clinical outcomes, such as mortality or morbidity, beyond blood pressure or symptoms, were predominantly skewed towards small-scale investigations, raising concerns regarding their reliability. Most studies on midodrine were short-term, and previous research showed possible tolerance following long-term use of the α-1 adrenergic receptor modulator9. Additionally, a recent study has reported higher mortality and morbidity rates associated with midodrine use in IDH10. However, this study had significant differences in baseline characteristics between the treatment and control groups and a lack of clear criteria for midodrine prescription, making it challenging to establish a definitive association with mortality. Consequently, additional large-scale studies are necessary to identify the implications of midodrine use in patients undergoing HD. We aimed to evaluate the impact of midodrine use in patients undergoing HD using a large sample of real-world data.

Methods

Data source and study population

We analyzed the dataset from the 4th to 7th HD quality assessment programs conducted by the Health Insurance Review and Assessment (HIRA) of the Republic of Korea. Briefly, HIRA performs periodic HD quality assessments to improve the prognosis of patients undergoing HD by improving each HD center’s quality11. We analyzed data from the 4th (July and December 2013), 5th (July and December 2015), 6th (March and August 2018), and 7th (October 2020 and March 2021) phases, which included adult patients (≥ 18 years) who had been undergoing maintenance HD (≥ 3 months and ≥ 2 times weekly).

The number of participants in the 4th, 5th, 6th, and 7th programs was 21,839, 35,496, 31,238, and 38,729, respectively. Of 127,302 patients, we excluded repeated participants or patients with insufficient datasets (n = 53,999). Patients who underwent HD using a catheter were also excluded to as they were considered to be patients with special medical conditions, such as those with limited life expectancies (n = 1,763). This study included 71,540 patients. The institutional review board of Yeungnam University Medical Center approved this study (approval no. YUMC 2023-12-012). Informed consent was waived because patients’ records and information were anonymized and de-identified before the analysis.

Exposures

Table S1 shows medication codes. The prescription of midodrine through one pill or more during the 6 months of each HD quality assessment period was considered the use of midodrine. We divided the participants into two groups based on the prescription of midodrine: the No-prescription group, patients without a prescription of midodrine, and the Midodrine group, patients with a prescription of midodrine. We divided patients in the Midodrine group into two groups as follows: the Low group, patients with a prescription of midodrine of < 30 pills, and the High group, patients with a prescription of ≥ 30 pills of midodrine. Additionally, we divided patients based on the prescription of midodrine and anti-hypertensive drugs into four groups: the NN group, patients with no prescriptions of midodrine and anti-hypertensive drugs; the NY group, patients with no prescription of midodrine but were prescribed anti-hypertensive drugs; the YN group, patients with a prescription of midodrine but no prescription of anti-hypertensive drugs; and the YY group, patients with prescriptions of midodrine and anti-hypertensive drugs.

Study’s variables

The dataset included data on several factors, including age, sex, HD vintage (in months), the underlying cause of end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), and vascular access type. Additionally, various laboratory and clinical findings were recorded as part of the assessment, which included body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), hemoglobin (g/dL), Kt/Vurea, serum albumin (g/dL), serum calcium (mg/dL), serum phosphorus (mg/dL), serum creatinine (mg/dL) levels, and ultrafiltration volume (in L/session). These data were collected monthly, and all laboratory values were averaged from the monthly collected values. Kt/Vurea was calculated using the Daugirdas equation12.

Medications such as anti-hypertensive drugs, aspirin, clopidogrel, and statins were evaluated. Medication use was defined as one or more prescriptions identified during the HD quality assessment program for these medications. Before assessing the HD quality assessment program, comorbidities were evaluated over 1 year. Comorbidities were defined using the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), which encompasses 17 comorbid conditions13,14. CCI scores were computed for all patients. Definitions of the CCI and calculation of CCI score were analyzed using protocols defined from previous studies14. Additionally, the presence of myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure (CHF), or peripheral vascular disease was identified based on International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes.

Outcomes

Patients were followed up until June 2024. We evaluated patient survival as the primary outcome and cardiovascular events (CVEs) as the secondary outcome. CVE was defined as a composite of MI, stroke, and revascularization with or without death15,16. All diagnoses were evaluated using the ICD-10 codes and medical treatment, procedure, or operation codes according to definitions from previous studies17. ICD-10 codes were I21, I22, and I23 for MI; I60, I61, and I62 for hemorrhagic stroke; and I63 for ischemic stroke. The procedural or operation code was M6551-2, M6561-4, M6571-2, and M6601-2 for percutaneous intervention, and O1641-2, O1647, OA641-2, and OA647 for coronary artery bypass grafting. Medical treatment was 635801BIJ for protein C, 223501BIJ or 223502BIJ for tissue plasminogen activator, 450302BIJ or 450301BIJ for tenecteplase, 240201BIJ or 240230BIJ for tirofiban, and 246401BIJ, 246405BIJ, 246407BIJ, 246404BIJ, or 246406BIJ for urokinase. Patients transferred for peritoneal dialysis or kidney transplantation without an event were considered to have been censored at that time.

Statistical analyses

The data were analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide version 7.1 and R version 3.5.1. Categorical variables were represented as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were represented as means and standard deviations. The statistical significance of differences between categorical variables was assessed using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Differences between continuous variables were assessed using the t-test. A one-way analysis of variance was used to compare continuous variables across the three groups. For multiple comparisons, the Tukey post-hoc test was used, which provides adjusted p-values, accounting for multiple testing.

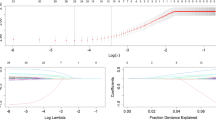

Due to substantial differences in the baseline characteristics between the No-prescription and Midodrine groups, propensity analysis was performed to minimize bias. To balance the baseline characteristics between the No-prescription and Midodrine groups, we estimated propensity scores using logistic regression models for the following variables: age, sex, HD vintage, BMI, underlying cause of ESKD, CCI score, vascular access type, Kt/Vurea, ultrafiltration volume, hemoglobin, serum albumin, serum phosphorus, and serum calcium levels, serum creatinine, the use of anti-hypertensive drugs, aspirin, clopidogrel, or statins, and the presence of MI or CHF, or peripheral vascular disease. Participants in the Midodrine and No-prescription groups were matched in 1:3 ratios without replacement and with a matching tolerance (caliper) of 0.2; the nearest neighborhood matching was based on propensity scores.

Survival curves were estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves. P-values for the comparison of survival curves were determined using the log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HRs) and confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using Cox regression analyses. Multivariable Cox regression analyses were adjusted for age, sex, BMI, underlying cause of ESKD, vascular access type, CCI score, HD vintage, ultrafiltration volume, Kt/Vurea, hemoglobin, albumin, creatinine, phosphorus, and calcium serum levels, and the use of antihypertensive drugs, aspirin, clopidogrel or statins, the presence of MI or CHF, or peripheral vascular disease. Multivariable Cox regression analyses were performed using the enter mode. In the propensity-score-matched cohort, multivariable analyses were performed using only variables with a P value < 0.2 for differences between the two groups after propensity score matching. Additionally, we performed subgroup analyses based on age, sex, HD vintage, antihypertensive drug use, diabetes, MI or CHF, and CCI score. We performed the CVE-free survival analysis by excluding individuals with any diagnoses, procedures, or treatments related to CVEs during the HD quality assessment period and within the previous year. Furthermore, Schoenfeld residual analysis for each variable were evaluated to assess the proportional hazard assumption. The Schoenfeld residual analysis of the Cox regression showed that the rho values for all variables were within the range of -0.1 to 0.1, indicating weak correlations between the variables and time, suggesting that the proportional hazard assumption was generally satisfied. Although some variables, such as age, body mass index, CCI score, the use of clopidogrel or statins, or peripheral vascular disease, were significant (P < 0.05), no specific trends in the Schoenfeld residual plots were detected over time. These variables were either not included as key variables in the main analysis or were used in some subgroup analyses and are therefore unlikely to have significantly influenced the overall results. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The numbers of patients in the No-prescription and Midodrine groups were 64,651 and 6,889 before matching and 20,305 and 6,887 after matching, respectively. Approximately 9.6% of all patients were prescribed midodrine. Table 1 describes baseline characteristics before and after propensity score matching. Before matching, the Midodrine group included older and more female participants with a higher prevalence of comorbidities and a lower proportion of the use of anti-hypertensive drugs than that in the No-prescription group. In addition, the Midodrine group had a similar HD vintage and ultrafiltration volume, and lower serum albumin, serum phosphorus, and serum creatinine than those in the No-prescription group. Most variables differed significantly between the two groups before matching; however, the differences were attenuated after matching. Figure S1 shows the distribution of propensity scores before and after matching. Before matching, when divided into three groups—No-prescription, Low, and High—for most variables, the Low group tended to be positioned either between the No-prescription and High groups or closer to the High group (Table S2).

Midodrine prescription and incidence of all-cause mortality and CVE

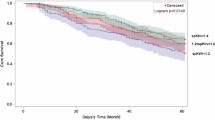

After matching, follow-up durations in the No-prescription and Midodrine groups were 52 ± 59 and 53 ± 59 months, respectively. The numbers of deaths in the No-prescription and Midodrine groups were 9,530 (46.9%) and 3,443 (50.0%), respectively (P < 0.001). Figure 1 shows the survival curves in cohorts with propensity score matching. The 5-year patient survival rates in the No-prescription and Midodrine groups were 62.6% and 58.0%, respectively (P < 0.001). Univariate and multivariable Cox regression analyses using cohort before and after matching revealed a higher HR for patient mortality in the Midodrine group than that in the No-prescription group (adjusted HR after matching: 1.16, 95% CI 1.12–1.21, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

The 5-year CVE-free survival rates in the No-prescription and Midodrine groups were 74.3% and 74.9%, respectively (P = 0.670). In multivariable Cox regression analyses, no significant difference was observed in CVE between the two groups (Table 2).

Midodrine dose and incidence of all-cause mortality and CVE

Additionally, we performed survival analyses among the No-prescription, Low, and High groups (Figure S2). The 5-year patient survival rates in the No-prescription, Low, and High groups were 62.6%, 63.2%, and 55.3%, respectively (P < 0.001 for No-prescription vs. High groups; P = 0.810 for No-prescription vs. Low groups; P < 0.001 for Low vs. High groups). The High group had a higher HR for patient mortality than that in the No-prescription or Low groups (Table 2).

The 5-year CVE-free survival rates in the No-prescription, Low, and High groups were 74.3%, 76.2%, and 74.1%, respectively (P = 0.850 for No-prescription vs. High groups; P = 0.320 for No-prescription vs. Low groups; P = 0.340 for Low vs. High groups). Multivariable Cox regression analyses showed no differences in CVE among the three groups (Table 2).

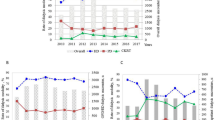

Midodrine prescription and clinical outcomes in subgroup analyses

We performed subgroup analyses by sex, age, HD vintage (30 months as median value), CCI score (nine as median value), the presence of diabetes, the use of anti-hypertensive drugs, or the presence of heart disease (MI or CHF). Regarding all-cause mortality using multivariable analyses, the Midodrine group was associated with an increased risk than that in the No-prescription group in all subgroups (Fig. 2). For CVE, multivariable Cox regression analyses showed that the Midodrine group had greater HR than that in the No-prescription group in subgroups of CCI score ≥ 9 (Figure S3). However, the Midodrine group had a lower HR than the No-prescription group in subgroups with a CCI score < 9.

Forest plots of the hazard ratio and 95% confidence interval for patient mortality according to subgroups (A, univariate; B, multivariable). Multivariable analyses were adjusted for age, sex, underlying disease of end-stage kidney disease, body mass index, Charlson comorbidity index score, vascular access type, hemodialysis vintage, ultrafiltration volume, Kt/Vurea, hemoglobin, albumin, creatinine, phosphorus, and calcium serum levels, the use of anti-hypertensive drugs, aspirin, clopidogrel, and statins, and the presence of myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure and peripheral vascular disease. Values were expressed as hazard and 95% confidence interval for the Midodrine group compared to the No-prescription group. In multivariable analyses, P-values of subgroup interaction were 0.494 for age, 0.371 for HD, 0.123 for sex, and < 0.001 for CCI score, DM, anti-HTN drug, or heart disease. anti-HTN anti-hypertensive, CI confidence interval, CCI Charlson comorbidity index score, DM diabetes mellitus, HD hemodialysis vintage, HR hazard ratio.

Because patients with IDH are more likely to receive normal saline prescriptions, we performed a subgroup analysis comparing patients who were prescribed ≥ 500 mL of saline over a 6-month period with those who were not. The respective numbers of patients with and without saline prescriptions were 13,990 and 57,550. In both subgroups, the use of midodrine was significantly associated with elevated all-cause mortality, while its association with CVEs was not statistically significant (Table S3). The interactions of all-cause mortality and CVEs with saline prescription were also not significant, with respective interaction P-values from univariable and multivariable models being 0.200 and 0.278 for all-cause mortality, and 0.468 and 0.296 for CVEs.

Midodrine and anti-hypertensive drug prescriptions and clinical outcomes

Additionally, we compared the outcomes based on the prescription of midodrine and anti-hypertensive drugs (Figure S4). In cohort before matching, the 5-year patient survival rates in the NN, NY, YN, and YY groups were 73.0%, 66.8%, 60.1%, and 57.2%, respectively. In the cohort after matching, the 5-year patient survival rates in the NN, NY, YN, and YY groups were 68.5%, 60.6%, 60.1%, and 56.8%, respectively. In multivariable Cox regression analyses, the YN or YY group was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality than that in the NN or NY groups in cohort before or after matching (NN vs. YN: adjusted HR after matching: 1.31, 95% CI 1.21–1.41, P < 0.001; NY vs. YN: adjusted HR after matching: 1.10, 95% CI 1.03–1.18, P = 0.007); however, there was no significant difference between NN and NY groups in total cohort and between YN and YY groups in both cohorts (Table S4). Anti-hypertensive drugs showed a weak association with all-cause mortality within both the Midodrine and No-prescription groups.

In the cohort before matching, the 5-year CVE-free survival rates in the NN, NY, YN, and YY groups were 80.9%, 75.5%, 79.6%, and 72.7%, respectively. In cohort after matching, the 5-year CVE-free survival rates in the NN, NY, YN, and YY groups were 77.8%, 72.7%, 79.7%, and 72.7%, respectively. In multivariable Cox regression analyses, the YY group had a greater HR for CVE than that in the NN group in the cohort after matching (adjusted HR after matching: 1.14, 95% CI 1.04–1.26, P = 0.006) (Table S4). For CVE, anti-hypertensive drugs tended to be more strongly associated with CVE than midodrine.

Discussion

In this large retrospective study, we observed that midodrine therapy was associated with a dose-dependent increased risk of all-cause mortality in patients on maintenance HD using data collected for HD quality assessment programs and their claims data. This study’s results were still significant after matching comorbidities and risk factors for IDH, such as ultrafiltrate volume.

In this study, approximately 10% of patients received midodrine. A recent study in Japan reported that approximately 15% of patients were administered oral vasopressors, including midodrine, which were associated with poor outcomes18. A study published in 2005 using 346 survey responses from 2,000 randomly selected dialysis clinics in the United States found that approximately 30% of respondents used midodrine for the proactive management of IDH19. A study from the United States in 2018 reported that only 0.3% of patients received midodrine10. The reason behind this marked difference in usage rates remains unclear, but may be related to the 2010 proposal by the United States Food and Drug Administration to withdraw the approval of midodrine hydrochloride due to insufficient post-marketing efficacy data, a decision later reversed following opposition from the medical community20. There are no clear guidelines for the use of midodrine in preventing or treating IDH; therefore, the use of midodrine depends on the preferences of the attending physicians and the regulatory approval in each country. This could influence the relationship between midodrine and outcomes. However, the studies mentioned above have also shown that midodrine use is associated with poor outcomes, suggesting that the findings of our study may apply regardless of more liberal or restrictive indications or cohorts.

The use of midodrine may be a surrogate marker of the incidence of IDH in patients undergoing HD. IDH is well known to increase the risk of CVEs and mortality in patients undergoing HD, and midodrine is often used in IDH therapy or prophylaxis4,5,6. In our study, although the proportion of MI or CHF was similar between the Midodrine and No-prescription groups after propensity score matching, the severity of HF or myocardial ischemia might be greater in the Midodrine group. Cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction and increased proinflammatory cytokines are known risk factors for IDH and mortality in patients undergoing HD21,22. Recent study reported that frequent IDH was associated with more newly recognized peripheral artery disease, suggesting that frequent IDH could be a be a sign of increased vascular stiffness or dysfunction23. Therefore, although midodrine increases blood pressure and alleviates IDH8it may not significantly improve clinical outcomes, which involve multiple pathophysiological processes beyond blood pressure per se. These findings are consistent with a recent observational study10.

There are concerns that midodrine-induced vasoconstriction and the resulting increase in peripheral vascular resistance may impair tissue perfusion despite the increase in blood pressure. Theoretically, midodrine produces arteriolar and venous vasoconstriction, which may increase blood pressure by increasing cardiac output due to increased venous return to the heart and peripheral vasoconstriction. However, when the decrease in intravascular volume due to delayed vascular filling during dialysis exceeds the increase in venous return caused by midodrine, the vasoconstriction caused by midodrine further reduces tissue perfusion and cardiac output. In a few studies, midodrine appears to be safe in patients with ischemic heart disease or peripheral vascular disease; however, these studies had small sample size, and safety in these patients is not well studied24,25,26,27. Furthermore, short-acting agents such as midodrine can increase blood pressure variability, which is a predictor of mortality in patients undergoing HD28. Conversely, some patients who experience IDH fail to maintain or increase arterial tone, presumably due to cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction29,30,31. In this study, a higher number of patients treated with midodrine had diabetes and cardiovascular disease, suggesting that these patients are more likely to have cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction32. Patients with cardiovascular autonomic dysfunction or those at high risk of developing this disorder may benefit from vasoconstrictors, such as midodrine. Prospective controlled trials are required to clarify the role, indication, and safety of midodrine in IDH treatment or prevention regarding clinical outcomes beyond blood pressure.

Midodrine is not the only measure to prevent IDH. Limiting the ultrafiltration rate by reducing interdialytic weight gain and increasing the time or frequency of dialysis sessions is associated with improved patient outcomes26,27,28 despite the difficulty of achieving it in clinical practice33,34,35. Cooling dialysate can help prevent IDH and its associated complications, such as myocardial stunning and brain white matter changes36,37. Avoiding eating food during dialysis and not taking anti-hypertensive medication before dialysis sessions are simple ways to prevent IDH4. On the contrary, there is no evidence that midodrine prevents the complications of IDH. Therefore, the combination of several measures, in addition to midodrine, should be considered in patients at high risk for IDH.

The association between midodrine and CVE was not evident in our study. IHD is known to be an essential risk factor for CVE4and midodrine is prescribed primarily for the treatment of IHD in patients undergoing HD. In contrast, the definition of CVE in our study mainly reflects atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, while it does not adequately reflect deaths related to HF or cardiac arrhythmias. Therefore, the use of midodrine may be more likely to be associated with non-atherosclerotic CVE than with arteriosclerotic CVE or may be associated with an increased risk of death from other causes, such as infection, that reflect the patient’s overall health. Interestingly, in subgroup analyses, midodrine was associated with a reduced risk of CVE when the comorbidity burden was low, whereas midodrine was associated with an increased risk of CVE when the comorbidity burden was high. The reasons for these results are unclear, but it is possible that midodrine use in patient with lower comorbidity burden reflects higher interdialytic weight gain due to good intake or more strict volume control. However, the presence of hypotension requiring midodrine use suggests a possible underlying decline in cardiovascular function compared to patients with normal or high blood pressure. These patients are expected to have a higher risk of exposure to CVE risks, such as decreased coronary blood flow during dialysis, despite the use of midodrine. Ultimately, it seems that the underlying decline in cardiovascular function, rather than the use of midodrine itself, is more likely to have contributed to the occurrence of CVEs. In fact, significant subgroup interactions with midodrine use and all-cause mortality or CVE occurrences were observed in subgroup analyses, including factors such as CCI score, diabetes mellitus, antihypertensive drugs, and heart disease. Further research is needed to determine the cause of death associated with the use of midodrine.

In our study, approximately half of the patients taking midodrine were prescribed anti-hypertensive drugs. We hypothesized that these patients would have a poorer prognosis than those not taking anti-hypertensive drugs due to greater blood pressure variability. In our study, as expected, patients taking midodrine and anti-hypertensive drugs had the highest trend of risk of CVE, despite weak statistical significance in multivariate analyses. However, when it came to the risk of all-cause mortality, the use of anti-hypertensive drugs was not a significant risk factor compared with midodrine. This relationship between anti-hypertensive drugs and mortality can be explained, at least in part, by the fact that the relationship between blood pressure and the risk of death or cardiovascular disease in patients undergoing dialysis is U-shaped38,39.

Our dataset did not include clinical data associated with IDH and there is no ICD-10 code for intra-dialytic hypotension. Because patients with IDH are more likely to receive normal saline prescriptions, we performed a subgroup analysis comparing patients who were prescribed ≥ 500 mL of saline over a 6-month period with those who were not. These findings suggest that midodrine prescription may independently affect all-cause mortality regardless of the occurrence of IDH. Although the presence or absence of saline prescription does not precisely define IDH events—and saline may also be prescribed for other purposes such as priming (although most centers use dialysate for priming) or to prevent membrane clotting during dialysis—saline use remains the only available proxy for identifying IDH events in the current dataset. Due to limitations of our dataset, a comprehensive evaluation of IDH could not be achieved in our study. To more accurately define and validate IDH events, future studies incorporating medical chart reviews or intradialytic blood pressure data will be necessary.

Our study has several limitations. First, our retrospective observational study is highly prone to selection bias regarding midodrine prescriptions. Therefore, as noted earlier, no conclusions can be drawn regarding the causal relationship between midodrine prescription and outcomes due to the potential confounding factors, especially IDH. We could not adequately capture information such as the frequency or severity of IDH and the severity of preexisting cardiovascular diseases. With retrospective studies alone, it is challenging to overcome ‘confounding by severity’, as treatments such as midodrine are more frequently applied to patients with more severe illness, leading to an apparent association between these treatments and poor outcomes. Second, we could not determine whether measures to prevent IDH other than using midodrine were being adequately taken. For example, increasing in dialysis time or frequency to limit the ultrafiltration rate may improve patient outcomes and limit the need for midodrine prescriptions. Therefore, these measures to prevent IDH may be critical confounding factors in the relationship between midodrine and prognosis. Finally, the limited data makes it impossible to determine the reason why midodrine was prescribed. The majority of prescriptions in patients undergoing HD were presumably for the prevention or treatment of IDH; however, some patients may have received midodrine for orthostatic hypotension or low interdialytic blood pressure. The results of our study should be interpreted with more caution in patients receiving midodrine for reasons other than IDH.

Despite these limitations, our study confirms that the association of the use of midodrine and an increased risk of mortality and paves the way for further research on the use of midodrine and outcomes in patients undergoing HD. Moreover, our results may serve as a wake-up call for physicians caring for patients undergoing HD to be more concerned about the patient’s general medical condition and prognosis, in addition to blood pressure, especially if patients require frequent midodrine use.

In conclusion, the use of midodrine was associated with a dose-dependent increased risk of all-cause mortality in patients on maintenance HD, although causality was uncertain. Consequently, we should actively search for and treat comorbidities and risk factors for IDH in patients on HD requiring midodrine, especially frequent dosing. Prospective studies are required to clarify the causal relationship between midodrine and mortality and to identify patient groups that may benefit from midodrine treatment. The findings should be interpreted with caution due to the observational nature of the study and should be validated in future prospective studies incorporating comprehensive IDH data.

Data availability

The raw data were generated by the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. The database can be requested from the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service by sending a study proposal including the purpose of the study, study design, and duration of analysis through the web site (https://www.hira.or.kr). Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (SHK) on request.

References

Bello, A. K. et al. Epidemiology of haemodialysis outcomes. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 18, 378–395. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-022-00542-7 (2022).

Roberts, M. A., Polkinghorne, K. R., McDonald, S. P. & Ierino, F. L. Secular trends in cardiovascular mortality rates of patients receiving dialysis compared with the general population. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 58, 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.01.024 (2011).

Longenecker, J. C. et al. Traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors in dialysis patients compared with the general population: the CHOICE Study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, 1918–1927. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.asn.0000019641.41496.1e (2002).

Stefánsson, B. V. et al. Intradialytic hypotension and risk of cardiovascular disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 9, 2124–2132. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.02680314 (2014).

Daugirdas, J. T. Pathophysiology of dialysis hypotension: an update. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 38, S11-17. https://doi.org/10.1053/ajkd.2001.28090 (2001).

Kanbay, M. et al. An update review of intradialytic hypotension: concept, risk factors, clinical implications and management. Clin. Kidney J. 13, 981–993. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfaa078 (2020).

McTavish, D. & Goa, K. L. Midodrine. A review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use in orthostatic hypotension and secondary hypotensive disorders. Drugs 38, 757–777. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-198938050-00004 (1989).

Prakash, S., Garg, A. X., Heidenheim, A. P. & House, A. A. Midodrine appears to be safe and effective for dialysis-induced hypotension: a systematic review. Nephrol. Dial Transplant 19, 2553–2558. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfh420 (2004).

Vincent, J., Dachman, W., Blaschke, T. F. & Hoffman, B. B. Pharmacological tolerance to alpha 1-adrenergic receptor antagonism mediated by terazosin in humans. J. Clin. Invest. 90, 1763–1768. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci116050 (1992).

Brunelli, S. M., Cohen, D. E., Marlowe, G. & Van Wyck, D. The Impact of Midodrine on Outcomes in Patients with Intradialytic Hypotension. Am. J. Nephrol. 48, 381–388. https://doi.org/10.1159/000494806 (2018).

Kang, S. H., Kim, B. Y., Son, E. J., Kim, G. O. & Do, J. Y. Comparison of Patient Survival According to Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agent Type of Treatment in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients. J. Clin. Med. 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12020625 (2023).

Daugirdas, J. T. Second generation logarithmic estimates of single-pool variable volume Kt/V: an analysis of error. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 4, 1205–1213. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.V451205 (1993).

Charlson, M. E., Pompei, P., Ales, K. L. & MacKenzie, C. R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 40, 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 (1987).

Kang, S. H., Kim, B. Y., Son, E. J., Kim, G. O. & Do, J. Y. Influence of Different Types of β-Blockers on Mortality in Patients on Hemodialysis. Biomedicines 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines11102838 (2023).

Farkouh, M. E. et al. Impact of Chronic Kidney Disease on Outcomes of Myocardial Revascularization in Patients With Diabetes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73, 400–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.044 (2019).

Kaikita, K. et al. Bleeding and Subsequent Cardiovascular Events and Death in Atrial Fibrillation With Stable Coronary Artery Disease: Insights From the AFIRE Trial. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 14, e010476. https://doi.org/10.1161/circinterventions.120.010476 (2021).

Kim, H. W. et al. Clinical significance of hemodialysis quality of care indicators in very elderly patients with end stage kidney disease. J. Nephrol. 35, 2351–2361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-022-01356-3 (2022).

Kanda, E., Tsuruta, Y., Kikuchi, K. & Masakane, I. Use of vasopressor for dialysis-related hypotension is a risk factor for death in hemodialysis patients: Nationwide cohort study. Sci. Rep. 9, 3362. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-39908-6 (2019).

Hossli, S. M. Clinical management of intradialytic hypotension: survey results. Nephrol Nurs J 32, 287–291; quiz 292 (2005).

Kuehn, B. M. Midodrine action. JAMA 304, 1317–1317 (2010).

Usui, N. et al. Association of cardiac autonomic neuropathy assessed by heart rate response during exercise with intradialytic hypotension and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 101, 1054–1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2022.01.032 (2022).

Yu, J. et al. Pro-inflammatory cytokines as potential predictors for intradialytic hypotension. Ren. Fail 43, 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886022x.2021.1871921 (2021).

Seong, E. Y. et al. Intradialytic Hypotension and Newly Recognized Peripheral Artery Disease in Patients Receiving Hemodialysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 77, 730–738. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.10.012 (2021).

Cruz, D. N., Mahnensmith, R. L. & Perazella, M. A. Intradialytic hypotension: is midodrine beneficial in symptomatic hemodialysis patients?. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 30, 772–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90081-0 (1997).

Cruz, D. N., Mahnensmith, R. L., Brickel, H. M. & Perazella, M. A. Midodrine is effective and safe therapy for intradialytic hypotension over 8 months of follow-up. Clin. Nephrol. 50, 101–107 (1998).

Cruz, D. N., Mahnensmith, R. L., Brickel, H. M. & Perazella, M. A. Midodrine and cool dialysate are effective therapies for symptomatic intradialytic hypotension. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 33, 920–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-6386(99)70427-0 (1999).

Alappan, R., Cruz, D., Abu-Alfa, A. K., Mahnensmith, R. & Perazella, M. A. Treatment of Severe Intradialytic Hypotension With the Addition of High Dialysate Calcium Concentration to Midodrine and/or Cool Dialysate. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 37, 294–299. https://doi.org/10.1053/ajkd.2001.21292 (2001).

Selvarajah, V., Pasea, L., Ojha, S., Wilkinson, I. B. & Tomlinson, L. A. Pre-dialysis systolic blood pressure-variability is independently associated with all-cause mortality in incident haemodialysis patients. PLoS ONE 9, e86514. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086514 (2014).

Converse, R. L. Jr. et al. Paradoxical withdrawal of reflex vasoconstriction as a cause of hemodialysis-induced hypotension. J. Clin. Invest. 90, 1657–1665. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci116037 (1992).

Nette, R. W. et al. Hypotension during hemodialysis results from an impairment of arteriolar tone and left ventricular function. Clin. Nephrol. 63, 276–283. https://doi.org/10.5414/cnp63276 (2005).

Shafi, T., Mullangi, S., Jaar, B. G. & Silber, H. Autonomic dysfunction as a mechanism of intradialytic blood pressure instability. Semin. Dial 30, 537–544. https://doi.org/10.1111/sdi.12635 (2017).

Goldberger, J. J., Arora, R., Buckley, U. & Shivkumar, K. Autonomic Nervous System Dysfunction: JACC Focus Seminar. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 73, 1189–1206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.064 (2019).

Wong, M. M. et al. Interdialytic Weight Gain: Trends, Predictors, and Associated Outcomes in the International Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Am. J. Kidney Dis. 69, 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.08.030 (2017).

Tentori, F. et al. Longer dialysis session length is associated with better intermediate outcomes and survival among patients on in-center three times per week hemodialysis: results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Nephrol. Dial Transplant 27, 4180–4188. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfs021 (2012).

Chertow, G. M. et al. Long-Term Effects of Frequent In-Center Hemodialysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 1830–1836. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2015040426 (2016).

Selby, N. M., Burton, J. O., Chesterton, L. J. & McIntyre, C. W. Dialysis-induced regional left ventricular dysfunction is ameliorated by cooling the dialysate. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 1, 1216–1225. https://doi.org/10.2215/cjn.02010606 (2006).

Eldehni, M. T., Odudu, A. & McIntyre, C. W. Randomized clinical trial of dialysate cooling and effects on brain white matter. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 26, 957–965. https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2013101086 (2015).

Mazzuchi, N., Carbonell, E. & Fernández-Cean, J. Importance of blood pressure control in hemodialysis patient survival. Kidney Int. 58, 2147–2154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1755.2000.00388.x (2000).

Jhee, J. H. et al. The optimal blood pressure target in different dialysis populations. Sci. Rep. 8, 14123. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32281-w (2018).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Joint Project on Quality Assessment Research, Republic of Korea (M20240320001). The epidemiologic data used in this study were obtained from the Periodic Hemodialysis Quality Assessment by HIRA. The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the study’s retrospective nature. De-identification was performed, and data usage was permitted by the National Health Information Data Request Review Committee of HIRA.

Funding

This work was supported by the Medical Research Center Program through the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning (2022R1A5A2018865), the Basic Science Research Program through the NRF of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Education (2022R1I1A3072966).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JJ and SHK conceptualized and designed the study and performed the analysis and interpretation of the data. JJ and SHK wrote the manuscript. YJL, BYK, and JYC generated and collected the data. JEL and JYD drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Yeungnam University Medical Center (approval no. YUMC 2023-12-012).

Informed consent

Informed consent was not obtained from the patients since the records and information of the participants were anonymized and de-identified before the analysis. The IRB of the Yeungnam University Medical Center also waived the need for obtaining informed consent (approval no. YUMC 2023-12-012).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jeon, J., Lim, Y.J., Kim, B.Y. et al. Midodrine and clinical outcomes in patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Sci Rep 15, 23600 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08029-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08029-8