Abstract

This study analyzed different contact theories and models for simulating rail wear in the turnout areas. The typical cross-sections of the high-speed turnout switch and frog areas are selected. Normal and tangential contact models of wheel-rail are compared. A vehicle-turnout coupling dynamic model is developed in the turnout area considering the actual rail profile, the continuous traction force, and the running resistance. In addition, different wear models, update steps, wear superposition, and filtering methods are investigated in the turnout area. A simulation program in the turnout area for rail wear damage is established and compared with experimental data. The results demonstrate that the normal semi-Hertz model and the tangential semi-Hertz-based FASTSIM algorithm suit the wheel-rail contact in the turnout area. The wear model based on wear work is selected for simulating wear in the turnout area with a updating wear step size of 0.05 mm. The proposed model provides accurate rail wear values in the turnout area compared to the traditional models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The congested passenger rail transit issue can be solved by increasing the speed and density of high-speed trains. However, it also increases track rails’ wear and fatigue, especially in complex switch areas with high-impact loads on the tracks1. Enhancing the structural irregularity because of joining two rails in the switch and frog area of high-speed turnouts affects wheel-rail interaction when vehicles pass through the switch. Consequently, it causes various issues in high-speed turnouts, including vertical wear of the main rail, gauge corner wear, and shelling damage. The abnormal rail wear in the switch area significantly affects the safety of vehicle passage and reduces the turnout’s service life. The abnormal wear in the turnout area results in increased roughness of the turnout rail profile and variation in the equivalent conicity between the wheel and the rail. Therefore, when high-speed trains pass through the turnout, the vehicle vibration acceleration and the lateral displacement of the wheelset increase dramatically, severely affecting passenger comfort.

Several studies have been reported on wheel-rail contact and rail wear in the turnout areas. For instance, Sugiyama et al.2 developed a wheel-rail contact model for two-point contact in turnouts based on the NUCARS software, and studied the influence of wheel-rail profiles on contact. Xu et al.3 used a finite element model to analyze the influence of small turnout rail bottom slope on wheel-rail wear for a subway turnout. Spangenberg4 analyzed the influence of wheel-rail profiles on the initiation of rolling contact fatigue cracks in the wheel-rail interface. Nielsen et al.5 developed a fatigue calculation program for the turnout area considering the Archard wear model and applying the Palmgren-Miner criterion and the Hertz contact theory. However, fatigue damage occurred in the non-contact area of the turnout rail during the calculation of this model. Ma6 compared the applicability of the Kik-Piotrowski, Ayasse-Chollet, and Sichani methods in the turnout area, and compared the results with those obtained from Kalker theory and elastic-plastic finite element method models. Burgelman et al.7 using the example of the 9th turnout curve rail wear in the Netherlands, conducted operational data analysis. They performed simulation calculations based on the indicators of wheel-rail forces and wheel-rail wear index, but did not establish a comprehensive wear model. Xu8 used the spline smoothing method to process the wear data, and this method demonstrates effective smoothing in the gently sloping areas of the rail profile. However, it has limitations when applied to the junction of switch-connected rail sections. Yang9 and Chang10 pointed out that in the study of wheel-rail wear, using 0.1 mm as the wear surface updating step can better meet the requirements for updating the wheel-rail profile in the interval track. Yang et al.11,12 established a vehicle-turnout dynamic model based on measured turnout data to study the influence of rail wear profile on the dynamic performance of vehicles passing through turnouts. Kisilowski et al.13,14 studied the variation of track stiffness along the longitudinal direction and developed a variable stiffness turnout support model. They investigated the wear of turnout rails at different passing speeds, providing a reference for the turnout support model. Sresakoolchai15 and Hamarat16 pointed out that the integration of machine learning models with accelerometer data demonstrates high applicability in special rail systems such as narrow-gauge and broad-gauge tracks, and achieves high accuracy in diagnosing the flood resilience of railway turnouts. Amparo17 investigated the issues present in current rail grinding designs, pointing out that optimizing grinding schemes can effectively improve grinding quality and reduce maintenance costs. Torstensson18 developed a finite element turnout model that incorporates elastic components such as variable cross-section rails, turnout sleepers, and rail pads, and conducted an analysis of the factors influencing vehicle vibration during turnout passage.

The published studies have shown that turnout research mainly focuses on their structural characteristics and the track substructure system using relatively simple vehicle-turnout models. The turnout rail profiles are relatively complex, and the wheel-rail wear and damage are severe. Only limited studies have investigated wheel-rail contact models in the turnout areas, rail wear calculation techniques, and data processing methods. However, three critical gaps persist in existing research: (1) Simplified vehicle-turnout models often neglect longitudinal dynamics (e.g., traction forces and running resistance), leading to underestimated creep effects on wear; (2) Fixed-parameter smoothing methods fail to adapt to the geometric complexity of turnout areas, distorting wear profiles; and (3) Validation of turnout-specific wear models remains fragmented, lacking alignment with operational wear patterns. Compared to existing research, this study introduces three novel contributions: (1) A vehicle–turnout coupled dynamic model was established, integrating continuous traction force and running resistance to account for the impact of longitudinal creep on rail wear. The traction model achieved maximum wear depths corresponding to 89.91% and 88.26% of the field measurements during straight and lateral turnout passages, respectively. (2) A customized adaptive filtering algorithm was developed for turnout rail wear data, achieving a smoothing level 297.32 times greater than that of median filtering. This algorithm can dynamically adjust the smoothing parameters to maintain geometric precision in complex turnout regions. (3) The applicability of the wheel–rail contact model and wear model in turnout regions was comprehensively validated, establishing a wear update step length of 0.05 mm for turnout areas and developing a turnout wear prediction model. This simulation program has been rigorously verified against field-measured wear curves under operational conditions to ensure its practical applicability.

The train-turnout dynamic model

The dynamic computational model is essential for studying the dynamic performance of vehicles crossing turnouts and wheel-rail wear. The vehicle-turnout coupled dynamic model consists of two sub-models: the vehicle and the turnout. The two sub-models are coupled together through a wheel-rail contact algorithm.

Train dynamic model

A high-speed train is a multi-body non-linear system comprising different components with multiple degrees of freedom (DOF)19,20. The dynamic simulation model comprises a single vehicle unit consisting of 15 rigid bodies, including one car body, two bogies, four wheelsets, and eight axle boxes. The basic model of the train set is established using the large-scale dynamic simulation software SIMPACK. SIMPACK offers robust multibody dynamic simulation capabilities and an efficient implicit integration solver, and it can seamlessly integrate with MATLAB, making it particularly suitable for simulating the complex interactions in the turnout environments. It possesses distinct advantages over other software. The widespread use of SIMPACK in rail dynamics research ensures that it can reliably handle the discontinuities and complex constraints unique to the turnout environments. The car body and the frame have 6 degrees of freedom: pitch, roll, yaw and longitudinal, lateral, and vertical translations. The wheelset has degrees of freedom for pitch, roll, longitudinal displacement, and yaw, while the axle box only has the pitching degree of freedom. The single car has a total of 42 independent degrees of freedom21. Note that secondary nonholonomic constraints-such as additional wheelset–rail spin or lateral slip ties beyond the standard rolling-contact formulation-are not modeled; including these would further reduce the system’s effective degrees of freedom. The train consists of six powered and two trailer cars. To realistically reflect the distribution of powered wheelsets and improve computational efficiency, the model only considers basic components and assumes the train configuration includes three powered cars and one trailer car. The vehicle dynamics model established in the paper utilizes the actual manufacturing parameters of the CRH380A EMU. The vehicle axle load is 15 t, the wheelbase is 2500 mm, the wheels adopt the LMa-type tread and the rolling circle diameter is 860 mm.

The vehicle dynamics model is established based on SIMPACK, where components such as the car body, frame, wheel-rail system, and axle box are connected by a series of suspension springs, dampers, arm positioning nodes, secondary suspension springs, secondary dampers, anti-roll torsion bars, anti-wobble dampers, traction rods, and lateral stops. The basic vehicle dynamics model remains consistent for both longitudinal and lateral passage through the turnout.

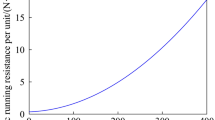

Many factors influence a vehicle’s running resistance. The vehicle’s acceleration is not considered due to the absence of the start-up and braking processes when high-speed trains pass through turnouts. At this moment, the traction force and running resistance experienced by the vehicle are equal in magnitude but opposite in direction, resulting in a constant vehicle velocity. Continuous traction force and running resistance negligibly impact the vehicle’s lateral and vertical dynamic performance. However, traction force can alter the wheel’s and rail’s creepage state, affecting wheel-rail wear22. The basic running resistance for different vehicle units is fitted based on the experimental data. The vehicle’s resistance can be divided into mechanical and aerodynamic. The basic running resistance per unit of the vehicle can be expressed as follows23:

.

In the equation:

w0 represents the basic running resistance per unit of the train, N/kN.

v represents the running speed of the train, km/h.

a, b, and c are constants related to the type of the vehicle, The term a represents the baseline mechanical resistance, bv captures the linear contribution of aerodynamic drag, and cv2 represents the quadratic aerodynamic effect. This formulation assumes steady-state operation with negligible acceleration. The studied vehicle parameters are a = 0.35, b = 2.40 × 10− 3, and c = 1.03 × 10− 4.

Two vehicle dynamic models were established based on vehicle design parameters to verify the impact of traction force and running resistance on track wear in the turnout area. In the traditional model, running resistance and continuous traction force are not considered, and the vehicle coasts freely. In the traction-resistance model, the continuous traction force experienced is evenly distributed as traction torque among the powered wheelsets of the three cars, while running resistance is evenly distributed among the four cars. Other parameters of the two vehicle models are the same besides traction and running resistance, and they both maintain constant-speed operation, with the train’s longitudinal passing speed at 350 km/h and lateral passing speed at 80 km/h. Train traction-resistance dynamic model as shown in Fig. 1. The dynamic model parameters were set according to TB/T 3301 − 2013, and the model’s accuracy was validated by comparing the vehicle’s vibration acceleration during turnout passage with the acceleration waveforms obtained from onboard measurements.

High-speed turnout model

Unlike in plain track, no superelevation is applied to the lateral curves in the turnouts. The turnout area includes rail bottom (top) slopes, ballasts, and tie plates under the rails. The turnouts comprise multiple rails and a complex structure. Therefore, the model cannot be replaced by rigid support, but instead, a turnout subgrade support system needs to be constructed. The sleeper and rail supported by the ballast are simplified in the dynamic simulation model as a rigid system with three DOFs: vertical, lateral, and lateral roll. The switch area support models are shown in Fig. 2.

Kisilowski14 noted that accounting for the dry friction characteristics and longitudinal stiffness variation of turnout rail support can enhance model calculation accuracy. These factors are particularly important when analyzing the longitudinal behavior of vehicles traversing turnouts. In this study, the vehicle system exhibits strong nonlinear characteristics, and track stiffness is generally several dozen times greater than the vehicle suspension stiffness. And this paper does not analyze longitudinal variations in vehicle characteristics. As such, to simplify the model and improve computational efficiency, the longitudinal variation in turnout support stiffness is ignored and assumed constant24. Referring to vehicle dynamics studies24,25, the ballast support, turnout sleepers, and rails are simplified into a rigid system with three degrees of freedom: vertical displacement, lateral displacement, and roll. In the model, the vertical support stiffness and damping are denoted by Kz and Cz, respectively, while Ky and Cy are the lateral support stiffness and damping. The rotational stiffness and damping are denoted as KΦ and CΦ, respectively. In future research, the more comprehensive support characteristics suggested in [14] can be incorporated to improve the model’s calculation accuracy.

The cross-sectional profile originates from the design drawings of the studied route. Representative cross-sectional profiles were obtained from the turnout design drawings, which provide only a limited number of processed cross sections in critical regions such as the switch and frog areas. Because these drawings do not capture the continuous variation of rail geometry along the turnout, interpolation was necessary to supplement additional cross sections. In SIMPACK, relying solely on the few provided cross sections for automatic interpolation can lead to abnormal intermediate profiles, especially in rail splice areas where the longitudinal spacing is large. To accurately reproduce the true turnout profile and to ensure that the update step is precise (i.e., when any cross section reaches the wear update criterion, all cross sections are updated), additional key cross sections were interpolated based on the identified critical geometric features. During interpolation, key inflection points of each cross-section were identified by tracking changes in the slope. The program separately discretized and interpolated the combined cross-sections in the switch and frog areas. The resulting cross-sections for the straight switch parts of the turnout are shown in Fig. 3.

When vehicles pass through lateral turnouts, the vehicle model and turnout support model are identical to those used for straight turnouts. However, lateral turnouts include structural elements such as transition curves and circular curves24. The lateral turnout model features a curve radius of 1100.72 m, a curve length of 54.44 m, and a transition curve length of 5.95 m, with no superelevation applied. Set the curve radius and transition curve for the vehicle’s lateral passage through the turnout according to the above parameters. By establishing a series of vertical section profile files for curved turnouts, 3D variable cross-section turnout profiles are generated using longitudinal interpolation. In the turnout simulation, the vehicle is assumed to travel at constant speed. The centripetal acceleration dominates under our turnout geometry and speed, whereas Coriolis acceleration and vertical lift acceleration are negligible. SIMPACK then handles only the remaining nonholonomic rolling contact constraints, and omitting Coriolis and lift terms reduces computational cost without sacrificing accuracy. The paper establishes a basic model based on SIMPACK, and further improves the vehicle-turnout dynamics model in conjunction with MATLAB programming software to study the wear model.

The wheel-rail contact model in the turnout

The intercity railway has surpassed the elliptical assumption of the Hertz contact theory. The model validates realistic contact models like semi-Hertz26, non-Hertz27, and FEMs. However, limited studies have been reported in the published literature on the wheel-rail relationship in switch areas. Moreover, the analysis and calculations of wheel-rail contact in switch areas still predominantly rely on the Hertz contact theory. This approach cannot capture the complex wheel-rail contact relationships in switch areas.

Normal contact model in turnout

The classical wheel-rail normal contact theories include the Hertz, semi-Hertz, Kalker non-Hertz contact theory, and the FEM. The finite element model surpasses the Half-space assumption, considers the non-linear characteristics of wheel-rail materials, and accurately reflects the contact state of the wheel-rail interface28. While FEM can resolve dynamic contact problems, its computational complexity and convergence challenges in large-scale dynamic simulations (e.g., iterative wear calculations with frequent profile updates) limit its practicality. Thus, in this study, FEM results are primarily used as a static reference to validate other contact models.

When vehicles pass through the turnout switch and frog areas, the wheel-rail normal force experiences significant fluctuations and varies with the operating conditions of the vehicle. The contact patch area and contact stress calculated by different normal models also change, further affecting the tangential force distribution and wheel-rail wear29. When the normal force changes, the calculation results of each normal contact model also vary, but the comparative results among the models remain similar. Using dynamics software, the paper establishes a vehicle-turnout dynamics model to calculate the wheel-rail normal force at the studied section under operational conditions. The wheel-rail normal force under these conditions is taken as an example and used as the input for comparative analysis of the studied normal contact models.

Tangential contact model in turnout

Creep force is the tangential force caused by relative sliding on the wheel-rail contact surface. The magnitude and direction of this force change with the train’s running trajectory, normal load, and the position of the wheel-rail contact point, thereby affecting wear distribution and profile evolution29,30. Therefore, further research on the wheel-rail tangential contact model and developing a tangential force model suitable for turnouts is particularly important.

The important tangential contact theories include Carter’s two-dimensional (2D) rolling contact theory, Johnson-Vermeulen’s 3D rolling contact theory, Kalker linear theory, Kalker simplified theory, Kalker exact theory, Shen-Hedrick model, and Polach creep force calculation model. These models and theories have certain limitations. For example, Carter’s 2D rolling contact model is unsuitable for solving 3D wheel-rail contact problems. Johnson-Vermeulen’s 3D rolling contact theory does not consider the spin creep effect between the two contacting bodies. Kalker’s linear theory neglects the Coulomb friction law within the contact patch and can be applied only with small creep and spin.

Simulation program for turnout rail wear

Rail wear simulation in the turnout zones encompasses a vehicle–turnout dynamics simulation system, selection of a wheel–rail rolling contact theory, adoption of a rail wear model tailored for the turnout areas, smoothing of the wear distribution, and strategies for rail surface and profile updating. To accurately capture the evolution of rail wear under wheel–rail interactions, the simulation of the turnout section (with a total passing weight of 30 Mt) was conducted over 141,180 iterations. A coupled simulation framework, integrating SIMPACK and MATLAB, was employed. In this framework, SIMPACK utilizes an implicit direct integration solver (SODASRT2) to resolve the vehicle–turnout dynamics, thereby ensuring numerical stability and accuracy. Detailed contact patch information is computed using a wheel–rail contact model, while the wear distribution under prevailing conditions is determined via a wear work model, with subsequent data processing performed using adaptive filtering. The wear depth is evaluated against updating criteria; if met, the rail profile is updated for the next iteration, otherwise, the subsequent iteration proceeds without profile updating. The simulation process of turnout rail wear is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Rail wear model for turnout

Kalker29 pointed out that the dynamic variation of wheel-rail forces directly affects wheel wear calculations and described two methods to obtain wheel-rail forces: through dynamic model simulation or through field measurements. Kalker utilized measurement vehicles from the Netherlands Railways to record the dynamic changes in wheel-rail contact motion, obtaining wear data for the Amsterdam Metro. He compared wear distributions under different track conditions. The measurement methodology provided critical support for wear modeling and validation, enabling more accurate predictions of profile evolution through detailed records of wheel-rail contact forces and material parameters.

The wear simulation process in this paper is as follows: the vehicle-turnout coupled dynamics simulation is used to obtain the wheel-rail contact relationship. The contact model is then invoked to calculate information such as contact patch location, creepage within the patch, and distributions of normal and tangential forces. Next, the wear distribution under the current operating conditions is calculated using the wear work model. After adaptive filtering of the data, the wear distribution is evaluated. If the maximum wear depth exceeds the update criterion, the profile needs to be updated, and the vehicle-turnout dynamic parameters must be recalculated for the next round of simulation. If the wear depth is less than the update criterion, there is no need to update the profile, and the next round of simulation can be initiated directly.

According to the above process, the study in this paper first needs to select a model suitable for calculating wheel-rail wear in the turnout zones. The existing wear calculation models can be divided into two main categories. The first is based on the wear volume and sliding friction, such as the Archard31 wear model. The other is based on energy consumption, such as wear models based on wear index32, wear work33, and the Zobory34 wear model. A suitable model for switch zone rail wear can be selected by analyzing the wear calculation mechanisms of different models and comparing their accuracy and computational speed. During the simulation, referencing the actual turnout crossing conditions of the vehicle, the normal load between the wheel and rail is N = 62.64kN, and the allowable adhesion coefficient is f = 0.35. Details of the wear model implementation—including wear coefficient selection, sliding distance computation, constraint handling, and iterative profile updates—are given in Li35.

Smoothing methods for turnout rail wear

The distribution of steel rail wear exhibits jagged fluctuations in the simulation of switch areas that deviate from the actual situation. Smoothing techniques are applied to the wear distribution to remove the jagged noise distribution and obtain realistic results. This is particularly important in switch areas with rail cuttings and multiple rail joints. If the smoothing method fails to accurately predict the magnitude and distribution range of wear in the switch area, it can significantly impact the accuracy of the wear simulation. Since the wear depth per cycle is extremely small, the changes in the rail profile are also very limited. Therefore, the smoothing process is applied to the calculated wear distribution rather than directly to the rail profile. The smoothed wear distribution is accumulated, and once the wear depth reaches the update threshold, the smoothed values are subtracted from the corresponding positions on the rail profile to update its shape.

Limitations of existing smoothing methods

Moving average filtering36, median filtering37, and Gaussian filtering38 programs are used to investigate the wear characteristics of switch area sections. The Vondrak39 filtering method was introduced as the evaluation criterion to evaluate the performance of each model. This filtering method includes the fitting degree F and the smoothness S, indicating the accuracy of the actual data and the data noise, respectively. A lower F indicates a better fitting of the smoothed curve to the original curve, while a lower S indicates a smoother curve.

.

where the subscript q shows the total values 1, 2…, n; wq is the weight with positive real numbers, vq is the smoothed sequence, uq stands for the original data, and λ2 is a coefficient that controls the relative proportion of F and S.

Adaptive filtering for turnout

This paper proposes a rail wear data smoothing method called “Turnout Area Adaptive Filtering,” which can dynamically adjust the smoothing window width and weighting coefficients. Equidistant values are taken for the horizontal axis for any switch area wear curve. The horizontal spacing between adjacent points is denoted as Δxm. The default window length for curve smoothing is Nm0; the initial segment length is Nm for the curve segmentation, i.e., Nm = Nm0. The adaptive filtering method first computes the local curvature Pc of the wear data f(xmi), dynamically adjusting the smoothing window width Nm according to the changes in curvature. If Eq. (4) holds, the window length is adjusted as Nm=Nm·ka, and the specified conditions are re-evaluated. Here, ka denotes the window width adjustment coefficient.

The adaptive filtering method first computes the local curvature Pc of the wear data f(xmi), dynamically adjusting the smoothing window width Nm according to the changes in curvature.

.

In Eq. (4), J[U] is the nearest odd integer to U, U = 1/(Pc·Δxm).

If Eq. (5) holds, the window length is adjusted as Nm = Nm/ka, and the selected conditions are re-evaluated. This process is repeated until Eq. (5) holds, and the current Nm becomes the final segment length.

The adaptive filtering method determines the filtering method according to the equivalent curvature of the turnout wear curve in different sections, as shown in Eq. (6).

.

Where km1、km2 are empirical coefficients obtained from experiments.

The average residual εm and the residual standard deviation smε of the least squares fitting are calculated using Eq. (7) to (9). To determine the smoothing window length and scale parameter in one step, the following equations are used:

.

The smoothing window length Mm can be expressed as follows:

.

The initial value of the scale factor cm0 for the Gaussian kernel function is determined considering the window length Mm. Then, the scale factor is adjusted using the average residual εm to obtain the final scale factor σm, as expressed in Eqs. (11) and (12).

.

The weights wmi for each point are determined using the Gaussian kernel function (Eq. (13)), and the smoothing process is applied to this segment.

.

In adaptive filtering methods, smoothing parameters are determined through extensive sensitivity analysis of wear data and field data. Once the current segment processing is completed, another segment of data for adaptive smoothing is extracted from the endpoint of this segment using the same method. Then, the Hermite interpolation can be used for smooth joining. The adaptive filtering process is shown in Fig. 5.

Comparison and analysis of calculation methods

The applicability of the aforementioned calculation methods on switch area rail wear simulation was studied to establish a simulation program for switch area wear. The calculated results were compared and analyzed for different wheel-rail contact theories, wear models, and wear smoothing methods using a cross-section of the switch area. In this study, the train’s wheel and rail materials are ER8 and U71Mn, complying with Chinese standards GB/T 3448 − 2015 and GB/T 2585 − 2007. U71Mn rails exhibit a carbon content of 0.65–0.75 wt%, manganese 1.10–1.40 wt%, and hardness of 300 HB. ER8 wheels contain 0.50–0.60 wt% carbon, 0.60–0.90 wt% manganese, and hardness of 280 HB. The densities of both materials are 7.85 × 102kg/m2, the elastic modulus is 206 GPa, and the Poisson’s ratio is 0.3.

Comparison between wheel-rail contact models

Various contact programs were developed to select a wheel-rail contact model with high computational accuracy and speed for the switch area. As an example, a complex combination of the frog and main rail is used in the switch area. Different contact models’ computational accuracy and efficiency were evaluated via comparative analysis in both the normal and tangential directions, and the results were compared.

Normal contact model in the turnout

The normal contact behavior between the wheel and rail is influenced by the wheel normal contact force. As the wheel-rail normal force changes, the contact patch area and contact stress vary across different models, but the comparison results among the models remain consistent. Dynamic calculations indicate that when a vehicle passes through the turnout at different speeds and loads, the wheel-rail vertical force at the same section exhibits significant variations. To control variables, the scenario of a vehicle passing through the turnout at operational speed under standard operating conditions was selected. In this scenario, the wheel-rail normal force at the studied section is 62.64 kN.

The normal contact theory is analyzed using a combination of the LMA wheel tread, a straight switch rail (top width of 30 mm), and the 18th switch zone. The cross-section with a top width of 30 mm is a key section in the turnout design drawings. This section exhibits significant variations in the wheel-rail contact state under different lateral wheel shift conditions, making it ideal for comparing different contact models. The calculation considers the possibility of multiple contact points. When multi-point contact occurs in the wheel-rail interaction, the model separately computes and distributes the contact forces at the two points to accurately reflect the wheel-rail interaction. The lateral displacement of the wheelset, yw, is set at 0 mm, 3 mm, 6 mm, and 9 mm. Four models, namely Hertz, semi-Hertz, CONTACT, and FEM, are used to calculate the contact patch shape and stress distribution. The results are shown in Fig. 6.

The FEM results provide a reference for verifying other contact programs. In Fig. 5, numbers ①, ②, ③, and ④ are the calculation results of the Hertz, semi-Hertz, CONTACT, and FEM models, the contact area and maximum contact stress under the aforementioned conditions are shown in Table 1.

The contact between the wheel tread and the straight switch rail with a top width of 30 mm in the switch zone demonstrates that ellipses represent the Hertz contact patch for lateral wheel displacements of 0 mm and 3 mm. The results obtained from the semi-Hertz and Non-Hertz contact theories are similar to those obtained from the finite element model calculation. The Hertz contact model demonstrates the largest contact patch area and the lowest contact stress among the four wheel-rail contact models. The contact area is 25.99% larger, and the maximum contact stress is 45.55% lower than the finite element model. The Semi-Hertz and Non-Hertz models’ contact patch areas are 17.83% and 22.60% smaller than the finite element model. The contact stress in these models is 13.75% and 21.29% higher than the finite element model, respectively.

When the lateral displacement of the wheel ranges from 6 mm to 9 mm, the contact patch area between the wheel tread and the straight switch rail of the combined section decreases for the Hertz contact model, and the contact stress increases accordingly. Notably, at a lateral displacement of 9 mm, the contact patch area is 49.58% of the finite element contact patch. In contrast, the maximum contact stress is 60.28% higher than the finite element model. The results obtained from the semi-Hertz and Non-Hertz contact theories are similar. Their contact patch areas are 16.01% and 24.15% smaller than the finite element model. The maximum contact stress for both cases is higher by 7.97% and 18.25%, respectively, compared to the finite element model.

Since the Hertzian contact patch exhibits an elliptical distribution, its calculated contact patch shape and stress distribution deviate significantly from the results of finite element models when applied to the complex rail profiles in the turnout areas. Consequently, Hertzian contact theory fails to accurately simulate the wheel-rail contact behavior in the turnouts. In contrast, the contact patch shape, area, stress magnitude, and distribution obtained using the semi-Hertzian contact theory and Kalker’s non-Hertzian contact theory align more closely with finite element model results. These theories are more suitable for simulating wheel-rail interactions in the frog area. Under the same operating conditions, the computational efficiency of the semi-Hertzian contact model is tens of times higher than that of Kalker’s non-Hertzian contact model, providing a distinct advantage for large-scale wheel-rail contact simulations in turnout areas.

Tangential contact model in the turnout

This study analyzed Kalker’s simplified theory, Kalker’s precise theory, the Shen-Hedrick model, and the Polach calculation model. The CONTACT algorithm can accurately obtain parameters based on Kalker’s precise theory, such as the force distribution and stick-slip zone distribution inside the contact patch. Therefore, the results obtained from this model serve as a reference for comparing the tangential models of the wheel-rail contact40.

Corresponding creep force simulation programs were developed for the tangential force models discussed in the preceding sections. The wheel-rail contact with a straight switch rail top width of 30 mm and yw = 0 mm, 3 mm, 6 mm, and 9 mm in the switch area was studied. Then, a comparative analysis of the creep force magnitude was conducted for the FASTSIM model based on Hertz contact (referred to as FH), the FASTSIM model based on semi-Hertz contact (referred to as FSH), the Polach model, and the CONTACT model under different operating conditions, The calculation results indicate that under different yw conditions, the trends of the calculation results for each model are consistent. Taking the yw = 0 mm condition as an example for analysis, as shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7 shows that the longitudinal creep forces calculated by the four tangential force models are consistent with the creepage ratio under the pure longitudinal creep condition. Specific differences exist in the longitudinal creep forces among the models at lower creepage ratios. FH, FSH, and Polach models differ from the CONTACT program by a maximum of 5.73%, 4.98%, and 4.52%, respectively. The purely lateral creep condition exhibits similar trends to the pure longitudinal creep condition. Under the pure spin creep condition, for the models at a lower spin creep, the creep forces calculated by the four models increase with the spin creep ratio, and their values are pretty close. However, when the spin creep exceeds a certain value, the creep force from each model decreases with an increase in the spin creep ratio. The FH, FSH, and CONTACT models are relatively close at this point, with the Polach model differing from the CONTACT model by a maximum of 9.7%.

Under the same operating conditions, the calculation results of the FSH model are similar to those of the CONTACT model. The computation times for FSH and CONTACT are 0.12s and 10.17s, respectively, indicating that the computational efficiency of FSH is significantly higher than that of the CONTACT algorithm. This makes FSH more advantageous for large-scale data processing and more suitable for wheel-rail wear simulation. Therefore, this study adopts the FASTSIM algorithm, based on the semi-Hertzian approach, for turnout wheel-rail contact calculations.

When the contact materials satisfy the elastomer assumption, the semi-Hertz contact model can be considered for calculations. This model is particularly useful when wear is present on the wheel-rail or when the continuity of the wheel-rail profile is poor, as it allows for fast computation while maintaining accuracy.

Comparison of the turnout wear models

The Archard wear model, wear index model, wear work model, and Zobory model were employed to analyze and calculate wear using the same parameters, and the calculation results are shown in Table 2. The contact condition between the wheel and the straight switch rail with a top width of 30 mm in the switch zone is considered. The calculation results show that the wear calculated by different wear models obtained from various experiments distributes in the sliding zone of the contact patch, i.e., no wear is observed in the adhesive zone. The four wear models yield similar wear patterns in the contact patch. However, there are differences in the magnitude and distribution of wear among the models due to variations in the experimental conditions. Under the same wear calculation parameters, the maximum wear values obtained from the Archard wear model are 4.97 times, 4.67 times, and 10.95 times higher than those from the wear index, wear work, and Zobory models. And the wear range obtained from the Archard wear model are 1.44 times, 1.33 times, and 1.72 times higher than those from the wear index, wear work, and Zobory models.

The Archard wear model exhibits a longer computation time, 1.5 times, 5.4 times, and 1.9 times longer than the computation time of the wear index, wear work, and Zobory models, respectively. The calculation accuracy of the Wear Index Model is slightly lower than that of the Wear Work Model, and its computation time is 3.6 times longer than that of the Wear Work Model. The calculation results of the Zobory Model show a large deviation from the measured results. The computational results show that the wear work-based model provides results closer to the field-measured wear and has lower computational costs. The wear work model directly correlates wear volume with the frictional work done at the contact interface, effectively capturing energy dissipation during sliding. It adeptly handles the nonlinear relationship between frictional work and material loss in turnout contact zones. The Archard model uses a constant wear coefficient and a simplified wear volume formula that is linearly dependent on sliding distance and contact pressure, but it fails to account for energy dissipation effects, resulting in a relatively higher wear depth compared to other models, consistent with the published reports41. The simulation results show that the predictions of the wear work model are in high agreement with the field-measured wear curves, thereby confirming its engineering applicability. Therefore, when analyzing the wear of the switch rails, choosing the wear work-based model for simulation and analysis is recommended.

The wear work theory posits that the wear volume of a material is proportional to the wear work, with wear primarily occurring in the sliding region. Under the aforementioned assumptions, the wear work model can be widely applied to wear problems between materials such as wheel-rail and bearings.

The rail profile is updated when the profile changes by 0.1 mm for the wheel-rail wear simulation on the sectional track. However, the updated step size for the wheel-rail profile in switch areas has not been studied. The trace method investigates the correlation between the straight switch rail profile in the 18th switch and the matching wheel profile. Under the same contact conditions, the variation patterns of contact points for different sections are consistent. Taking the example of a section with a straight switch rail top width of 40 mm, the distribution of wheel-rail contact points for the original section (wear depth h = 0 mm) and wear depths of 0.04 mm and 0.05 mm are shown in Fig. 8.

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to evaluate wear depth thresholds (0.04 mm, 0.05 mm, and 0.06 mm). At 0.05 mm, the contact point distribution exhibited significant divergence from the original profile (Fig. 8c), marking a critical threshold for geometric accuracy. Smaller increments (e.g., 0.04 mm) showed negligible changes, while larger steps oversimplified wear progression. Thus, 0.05 mm balances computational efficiency and simulation fidelity.

Comparison of smoothing methods in the turnout

MATLAB was used to implement three smoothing methods and study the applicability of existing smoothing methods in the switch area: moving average filtering, median filtering, and Gaussian filtering. These filters were applied to typical switch area profiles and compared to the original wear data to analyze the smoothing results. The smoothing results of the three methods are shown in Fig. 9.

The computational results indicate significant differences between the smoothed depths of the three smoothing methods and the original wear data. Median filtering only removes outliers in each window, resulting in data like the original data in areas with smooth variations. However, there are fluctuations in the data at the highest point; therefore, some data points are erroneously removed. As a result, the median filtering does not accurately reflect the true wear distribution, and the overall smoothing effect is poor. The window width influences both Gaussian smoothing and moving average filtering. As the window width increases, the overall smoothness of the data increases. However, the data at the highest point significantly changes because of contraction deformation, altering the wear range. Methods that use a fixed window width and a fixed smoothing approach face a trade-off between smoothness and fitting accuracy in the final smoothing results.

The filtering analysis of the selected wear distribution in the switch zone using the adaptive filtering method is shown in Fig. 10.

Adaptive filtering eliminates the local random noise in the wear data compared to other methods while preserving the details and features. The filtered data aligns well with the original data in the wear initiation and the areas with abrupt wear changes caused by cutting in the straight switch rail. No scaling effect was observed in the wear range.

A comparative analysis was conducted on all the sections used in the switch model to evaluate the smoothing effectiveness of different models and the results are shown in Table 3. The four models’ smoothing of the wear data in each part performed similarly to the prior study on the typical section. After filtering, the average of the wear data was calculated to determine the wear characteristics of all sections. The median filtering showed poorer smoothness than the sliding average, Gaussian filtering, and adaptive filtering, with 103.73 times, 239.65 times, and 297.32 times higher, respectively. The data obtained through adaptive filtering better fits the original data. Since adaptive filtering requires assessing the wear distribution and performing piecewise smoothing, its computation time is slightly longer than that of other models; however, the computation time for all four smoothing methods remains within the order of 10− 3 or lower, ensuring very fast computational performance. Therefore, the proposed adaptive filtering algorithm was used to smoothen the wear data in subsequent wear analyses of the switch zone.

Adaptive filtering can be widely applied in areas such as signal denoising and data smoothing, especially in scenarios requiring real-time adjustment and optimization. In rail wear analysis, adaptive filtering can dynamically adjust the smoothing window based on different wear data, enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of data processing.

Validation of turnout simulation program based on field measurements

Based on the research results of the aforementioned wheel-rail contact models, wear models, and smoothing methods, a simulation program for switch zone rail wear was developed. The program incorporates a vehicle-switch coupling dynamics simulation to obtain the contact relationship between the wheel and rail. Moreover, the program utilizes information such as contact patch position, creepage rate within the contact patch, and the distribution of normal and tangential forces. The program calculates the rail wear distribution under the current operating conditions by applying suitable wheel-rail contact theories and wear models specifically designed for switch zones. The program also includes wear accumulation and data smoothing techniques to obtain the rail wear distribution for different passing loads. Two high-speed train models were used to simulate the rail wear in the straight and curved sections of the 18th turnouts and validate the accuracy of the developed simulation program for switch zone rail wear.

The No. 18 high-speed turnout model established in the paper is identical to the turnout parameters of the Dalian North to Yingkou East railway line in China. The operating vehicle on this line is the CRH380A EMU, whose parameters match those of the vehicle model in the paper. The straight and lateral speeds of the vehicle passing through the turnout are 350 km/h and 80 km/h, respectively. In actual operation, the total vehicle weight varies slightly with the number of passengers, but the simulation assumes a constant trainset mass. Rail maintenance adopts a grinding plan based on the total vehicle weight passing through. According to the existing grinding schedule for turnout rails, grinding is performed when the total passing weight reaches 30 Mt (16-car trainset passing 35,295 times). Upon reaching a cumulative traffic load of 30 million tons (Mt) on the turnout rail, wear profiles are immediately measured using the Miniprof profilometer. The simulation assumes identical cumulative loading conditions, constant trainset mass, 350 km/h straight-line passage speed, 80 km/h lateral passage speed, and invariant environmental parameters (temperature, humidity, lubrication). Prior to wear depth calculation, all rail cross-sectional profiles are geometrically aligned to a universal reference baseline to ensure spatial consistency in wear distribution analysis.

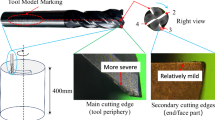

Specific sections were selected based on the turnout design drawings as typical cross-sections that are not influenced by the rail lowering near the switch base. For the straight switch rail, the cross‐section located 4821 mm from the tip was chosen; for the curved switch rail, the cross‐section at 7927 mm from the tip was selected. This selection ensures that the measured wear data accurately reflects the wear behavior under normal operating conditions. Based on the existing rail grinding plan, the rails were ground when the total passing load on the switch zone was 30 Mt. Therefore, the measured profiles were collected for the two selected sections under 30 Mt, as shown in Fig. 11. When the vehicle passes through the straight section of the turnout, the main form of rail wear is vertical wear on the top surface of the rail. On the other hand, as curved tracks exist in lateral turnouts, the lateral force between the wheel and rail increases to balance the residual acceleration caused by centrifugal force, resulting in predominant side wear on the curved switch rail profile. Severe wear occurs in specific areas of the rail within the turnout zone during straight and lateral turnout passages. The comparison of rail profile wear distributions derived from calculations and measurements is presented in Tables 4 and 5.

As analyzed from Tables 4 and 5, the traction model demonstrates significant improvements in error metrics compared to the traditional model. In straight turnouts, the mean absolute error (MAE) is reduced from 0.108 mm to 0.047 mm, while the root mean square error (RMSE) decreases from 0.111 mm to 0.047 mm, representing a 57% error reduction. For lateral turnouts, the MAE is reduced from 0.085 mm to 0.058 mm, and the RMSE decreases from 0.087 mm to 0.059 mm. These advancements are particularly pronounced at peak wear locations. Under identical conditions (30 Mt cumulative load, 350 km/h straight/80 km/h lateral operation, elastic track, excluding environmental and plastic deformation effects), the traction model exhibits better agreement with the curvature profiles and smoothness measured by Miniprof, validating its superior predictive capability. However, minor underestimation relative to experimental measurements persists due to unmodeled factors such as temperature variations, lubrication conditions, and plastic deformation effects.

The comparison between the simulated and measured wear of the turnout straight and curved rails is shown in Fig. 12 The results indicate that the maximum wear depth of the rail section calculated by the traditional model is 32.91 × 10− 2 mm under straight passing conditions, i.e., 39.60 × 10− 2 mm in the traction model. The maximum wear depth of the rail section measured from the data is 44.04 × 10− 2 mm. The maximum wear depths of the traditional and traction models are 74.72% and 89.91% of the measured data, respectively. The traditional model calculates the wear of the rail section, ranging from 7.42 mm to 33.50 mm, while the traction model corresponds to a wear range of 7.22 mm to 33.75 mm. The measured data shows a wear range of 6.48 mm to 35.96 mm. The wear distribution calculated by the traditional and traction models is similar under the same conditions. The traction model yields higher wear depths and larger wear ranges than the traditional model. The wear ranges calculated by both models are closely matched with the measured data. The measured wear width is approximately 13% higher than that predicted by the two models.

In the case of the curved switch rail, the traditional and traction models calculate the maximum wear depth of the rail section as 65.66 × 10− 2 mm and 86.16 × 10− 2 mm, respectively. The measured data shows a maximum wear depth of 97.62 × 10− 2 mm for the rail section. The maximum wear depths calculated by the traditional and traction models are 76.21% and 88.26% of the measured data, respectively. Both models show similar wear ranges for the rail section and are smaller than those observed in the measured data. The traction model considers traction forces and running resistance, increasing the longitudinal creep force and creepage ratio between the wheel and the rail. As a result, the traction model demonstrates maximum wear depth than the traditional model and is closer to the measured data.

To quantitatively evaluate model performance, we calculated the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE, where smaller values indicate closer predictions to actual values, representing better model performance) and the Coefficient of Determination (R², representing the fitting ability of different models, with values closer to 1 indicating closer alignment with measured results). For straight-direction turnout traversal, the RMSE of the traditional model and traction model were 0.060 mm and 0.027 mm respectively, with R² values of 0.84 and 0.97 respectively. For lateral-direction turnout traversal, the RMSE of the traditional model and traction model were 0.132 mm and 0.059 mm respectively, with R² values of 0.82 and 0.96 respectively. The results demonstrate that the traction model exhibits smaller errors and high consistency with the field-measured wear curves.

However, it should be noted that the simulation models do not consider the plastic flow of the wheel-rail interface. Moreover, the simulation environment does not consider variations in temperature, humidity, lubrication, and other external conditions in real operating conditions. High temperatures can soften rail steel, accelerating plastic deformation and adhesive wear, whereas low temperatures may increase brittleness and crack propagation. Humidity promotes oxidative wear through corrosion. While lubrication reduces friction and wear rates, it may also introduce third-body abrasives, potentially leading to abrasive wear under certain conditions. Future research that incorporates these factors could improve wear predictions under different operating environments.

Under straight passing conditions, the wear depths predicted by the traditional model and the traction model exhibit errors of 25.28% and 10.09% relative to the measured values, respectively. Specifically, the error attributable to traction-resistance amounts to 15.19%, while errors arising from environmental factors (temperature, humidity, lubrication) and model simplifications (material plasticity) account for approximately 10%. In the case of the curved switch rail, the wear depths predicted by the traditional model and the traction model deviate from the measured values by 23.79% and 11.74%, respectively. In this case, the error due to traction-resistance is 12.05%, while the error caused by environmental factors and model simplifications is 11.74%.

To study the wear rate of switch area rails, the rail wear profiles were measured and wear rates calculated when the total weight of EMUs passing through the turnout accumulated to 5Mt, 10Mt, 15Mt, 20Mt, 25Mt, and 30Mt. Using the established the turnout wear simulation program, the wear rates corresponding to the total weights were calculated. The distribution of measured and calculated wear rates for the two cross-sections is shown in Table 6.

The calculations given in Table 4 indicate that the wear rates of the turnout’s straight and curved rail sections decrease with increasing total axle load. The steel rail sections of the turnout experience higher wear rates when the total axle load is 5 Mt, indicating faster wear of the original rail profile in the turnout area where it contacts the wheels. As the rail wear increases, the contact patch area between the wheel and rail increases, decreasing contact stress and overall wear rate. In the longitudinal direction, the maximum difference between calculated values and measured values does not exceed 12%. Under straight passing conditions, when the wheelset passes through, the maximum difference between calculated values and measured values is 13%. The computational results indicate that the wear simulation using the traction model is more accurate and closely aligns with the measured data. Additionally, the computational speed of the traction model is comparable to that of traditional models. The developed simulation program for turnout rail wear provides reliable results that align with the measurements.

Conclusions

The paper establishes a model for the wear of turnout rails and validates it with measured data. The following conclusions can be drawn:

-

(1)

The FASTSIM algorithm based on the half-Hertz model is more suitable for the simulation of wheel-rail interactions in turnouts. When wheel-rail wear occurs or the continuity of wheel-rail profiles is compromised, the half-Hertz model proves to be particularly applicable and efficient.

-

(2)

A step length of 0.05 mm is the optimal choice for updating the wear depth of turnout rails. Considering both computational accuracy and efficiency, the wear work model is most suitable for simulating the wear of turnout rails. Under appropriate application conditions, the wear work model can be widely applied to wear calculations between materials such as wheel-rail interfaces and bearings.

-

(3)

The adaptive filtering algorithm is more suitable for filtering turnout rail wear data. Adaptive filtering can be applied to the filtering of most noise-affected signals, with particularly pronounced effects when abrupt changes occur in the input signal.

-

(4)

Compared with traditional models, the traction model produces a greater maximum wear depth, aligns more closely with measured data, and demonstrates higher computational accuracy. The results of the turnout rail wear simulation program are in good agreement with the measured data, underscoring the program’s advantages in simulating turnout rail wear.

This study investigates the dynamics and wear models of high-speed turnouts by establishing a high-precision simulation model and experimental validation methods. However, the following limitations should be noted: This study assumes constant external environmental conditions such as temperature and humidity, whereas in actual operations, environmental factors may affect the mechanical properties of track materials and the wheel-rail friction state. The model does not account for complex operational environments, such as uneven lubricant distribution, dynamic changes in vehicle load, and the impact of contaminants, which may lead to discrepancies between wear results and real-world conditions. Certain model assumptions may affect simulation accuracy to some extent.

To further enhance the accuracy and applicability of the model under actual working conditions, future research can be conducted in the following areas:

-

1.

Continuously collect wheel-rail wear data under actual operating conditions, particularly in environments with high temperatures, humidity, or rain and snow, to study the principles of various factors affecting wear and further validate the model’s reliability.

-

2.

Simulate dynamic temperature, humidity, lubrication, and contamination conditions on a rolling test rig by controlling the wheel-rail contact interface to evaluate the model’s applicability and performance under diverse external environments.

-

3.

Improve the turnout model and study the effects of key parameters on turnout rail wear under different operating conditions (e.g., vehicle speed and load variations).

Data availability

Data Availability StatementAll data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Additional datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Wiest, M. et al. Assessment of methods for calculating contact pressure in wheel-rail /switch contact. Wear 265, 1439–1445 (2006).

Sugiyama, H., Tanii, Y. & Matsumura, R. Analysis of wheel/rail contact geometry on railroad turnout using longitudinal interpolation of rail profiles. J. Omputat. Nonlinear Dynam.. 6 (2), 024501 (2011).

Jingmang Xu, P. et al. Effect of rail top slope on subway switch rail wear. J. Cent. South. Univ., 2014(8):2899–2904 .

Spangenberg, U. Influence of wheel and rail profile shape on the initiation of rolling contact fatigue cracks at high axle loads. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 54 (5), 638–652 (2016).

Nielsen, J. C. O., Palsson, B. A. & Torstensson, P. T. Switch panel design based on simulation of accumulated rail damage in a railway turnout. Wear 366, 241–248 (2016).

Ma, X. et al. Assessment of non-Hertzian wheel-rail contact models for numerical simulation of rail damages in switch panel of railway turnout. Wear, (432): 10–29. (2019).

Burgelman, N. et al. Switch panel wear loading-a parametric study regarding governing train operational factors. Veh. Syst. Dynamics: Int. J. Veh. Mech. Mobil., 2017(1):1–19 .

Xu, J. Research on Simulation of Curved Switch Rail Wear in high-speed Turnout (Southwest Jiaotong University, 2015).

Yang, Y., Jian, S. & Konngming, W. Research on low floor Tram wheel and rail wear under resilient wheels. China Mech. Eng., 32(4):439–445 . (2021).

Chang, C., Wang, C. & Jin, Y. Study on numerical method to predict wheel/rail profile evolution due to wear. Wear 269 (3), 167–173 (2010).

Pu Wang, S. et al. Adaptability analysis of high-speed turnout operation to reach speed under rail wear condition. J. Vib. Shock. 40 (19), 12–17 (2021).

Fei Yang, P. et al. The law of switch rail wear in high -speed turnout and its effect on dynamic performance. J. Railway Eng. Soc. 37 (3), 13–20 (2020).

Kisilowski, J. & Kowalik, R. Mechanical wear contact between the wheel and rail on a turnout with variable stiffness. Energies https://doi.org/10.3390/EN14227520 (2021).

Kisilowski, J. & Kowalik, R. Method for determining the susceptibility of the track. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app122412534 (2022).

Sresakoolchai, J. Integration of accelerometers and machine learning with BIM for railway Tight- and Wide-Gauge detection. Sensors 25 https://doi.org/10.3390/s25071998 (2025).

Sresakoolchai, J., Hamarat, M. & Kaewunruen, S. Automated machine learning recognition to diagnose flood resilience of railway switches and crossings. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29292-7 (2025).

Amparo Izquierdo, Domingo. Assessing the effectiveness of rail grinding trains. Lecture Notes netw. syst.. 357–366. (2022).

Li, X., Torstensson, P. T. & Nielsen, J. Simulation of vertical dynamic vehicle–track interaction in a railway crossing using green’s functions. J. Sound Vib. 410, 318–329 (2017).

Hao Wu, J. et al. Dynamic response analysis of high-speed train gearboxes excited by wheel out-of-round: experiment and simulation. Veh. Syst. Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1080/00423114 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Research on wear and grinding models of high-speed turnouts based on semi-Hertz contact. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-85016-5 (2025).

Jianwei Yao. Locomotive Vehicle Dynamics (Science, 2014).

Li, J. et al. Research on wheel/rail matching of metro vehicle under wheel damage. China Railway Sci. 39 (3), 71–78 (2018).

Qian Wang, Y. et al. Online calibration on the calculation parameters of trains basic resistance. Syst. Eng. 36 (12), 147–151 (2018).

Li, J. et al. High-speed turnout vehicle dynamics index research and vehicle dynamics calculation. Railway Standard Des. 64 (10), 6. https://doi.org/10.13238/j.issn.1004-2954.201910290006 (2020).

Ye, Y. et al. Wheel flat can cause or exacerbate wheel polygonization. Vehicle system dynamic. Int. J. Veh. Mech. Mobil. 58.DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/00423114 (2020).

Ayasse, J. & Chollet, H. Determination of the wheel rail contact patch in semi-Hertzian conditions. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 43 (3), 161–172 (2005).

Kalker, J. J. A fast algorithm for the simplified theory of rolling contact. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 11 (1), 1–13 (1982).

Chongyi, C., Wang, C. and Jin, Y. Numerical analysis of wheel rail wear based on 3D dynamic finite element mode. China Railway Sci. 29 (4), 89–95 (2008).

Kalker, J. J. & Chudzikiewicz, A. Calculation of the evolution of the form of a railway wheel profile through wear. Birkhäuser Basel. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-0348-7303-1_7 (1991).

Kisilowski, J. & Kowalik, R. Railroad turnout wear diagnostics. Sensors https://doi.org/10.3390/s21206697 (2021).

Archard, J. F. Contact and rubbing of flat surfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 24 (8), 981–988 (1953).

Pearce, T. G. & Sherratt, N. D. Prediction of wheel profile wear. Wear 144 (1–2), 343–351 (1991).

Kalker, J. J. Simulation of the development of a railway wheel profile through wear. Wear 150 (1–2), 355–365 (1991).

Zobory, I. Prediction of wheel/rail profile wear. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 28 (2–3), 221–259 (1997).

Li, J. Research on Turnout Wear and Fatigue Based on high-speed Train Crossing Dynamics. (Southwest Jiaotong University, 2022).

Alvarez-Ramirez, Jose, E., Rodriguez & Juan Carlos Echeverría. and. Detrending Fluctuation Analysis Based on Moving Average Filtering. Phys. Statist. Mechan. Appl. 354. 199–219. (2005).

Kravchonok, A. I., Zalesky, B. A. & Lukashevich, P. V. An algorithm for median filtering on the basis of merging of ordered columns. Pattern Recognit. Image Anal. 17 (3), 402–407 (2007).

Yoshizawa, S., Belyaev, A. & Yokota, H. Fast Gauss bilateral filtering. Comput. Graphics Forum. 29 (1), 60–74 (2010).

Xiang, W. et al. Application of Vondrak filtering method to the two-way satellite time and frequency transfer based on software defined receiver. Chin. Astron. Astrophy, (2):46. (2022).

Xu, J. et al. Comparison of calculation methods for wheel-switch rail normal and tangential contact. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit. (2016).

Ren Luo, J. et al. Simulation on wheel wear prediction of high-speed train. Tribology 29 (6), 551–558 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52305070) and Open Projects of the State Key Laboratory of Safety and Resilience of Civil Engineering in Mountainous Areas (HJGZ2024102).

Author contributions.

Jincheng Li is responsible for Writing-Original Draft in this paper, and has reviewed the entire manuscript. Min Hu provided significant assistance in the validation of the paper’s model and simulation results. Hao Wu provided the funding necessary for data collection, result validation, and simulation analysis in the paper. Hao Zhong contributed to the research and data collection in the study presented in the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jincheng Li is responsible for Writing-Original Draft in this paper, and has reviewed the entire manuscript. Min Hu provided significant assistance in the validation of the paper’s model and simulation results. Hao Wu provided the funding necessary for data collection, result validation, and simulation analysis in the paper. Hao Zhong contributed to the research and data collection in the study presented in the paper.All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Hu, M., Wu, H. et al. Numerical simulations and experimental analysis of high-speed turnout rails wear models. Sci Rep 15, 22680 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08065-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08065-4