Abstract

Robust differentiation between infarcted and normal myocardial tissue is essential for improving diagnostic accuracy and personalizing treatment in myocardial infarction (MI). This study proposes a hybrid framework combining radiomic texture analysis with deep learning-based segmentation to enhance MI detection on non-contrast cine cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging.The approach incorporates radiomic features derived from the Gray-Level Co-Occurrence Matrix (GLCM) and Gray-Level Run Length Matrix (GLRLM) methods into a modified U-Net segmentation network. A three-stage feature selection pipeline was employed, followed by classification using multiple machine learning models. Early and intermediate fusion strategies were integrated into the hybrid architecture. The model was validated on cine-CMR data from the SCD and Kaggle datasets.Joint Entropy, Max Probability, and RLNU emerged as the most discriminative features, with Joint Entropy achieving the highest AUC (0.948). The hybrid model outperformed standalone U-Net in segmentation (Dice = 0.887, IoU = 0.803, HD95 = 4.48 mm) and classification (accuracy = 96.30%, AUC = 0.97, precision = 0.96, recall = 0.94, F1-score = 0.96). Dimensionality reduction via PCA and t-SNE confirmed distinct class separability. Correlation coefficients (r = 0.95–0.98) and Bland-Altman plots demonstrated high agreement between predicted and reference infarct sizes.Integrating radiomic features into a deep learning segmentation pipeline improves MI detection and interpretability in cine-CMR. This scalable and explainable hybrid framework holds potential for broader applications in multimodal cardiac imaging and automated myocardial tissue characterization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) remains a leading cause of mortality worldwide, particularly among individuals over the age of 35, accounting for nearly one-third of deaths in this population1. Pathophysiologically, MI results from prolonged cardiac ischemia, which causes irreversible damage to the ventricular myocardium and leads to the formation of fibrotic scar tissue2,3. This post-infarction scarring substantially increases the risk of life-threatening arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death, thereby emphasizing the critical importance of early detection and accurate myocardial characterization to inform treatment strategies4,5. Although risk stratification tools are available, their limited specificity and dependence on demographic or clinical parameters often restrict their usefulness in personalized medicine6. Cardiac imaging has significantly advanced the diagnostic capabilities for MI by enabling direct visualization of ischemic and infarcted myocardial tissue7,8. Among imaging modalities, cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) is widely regarded as the gold standard, offering high spatial resolution and excellent soft-tissue contrast9. Quantitative measures derived from CMR, such as ventricular volumes and systolic function, serve as reliable predictors of clinical outcomes10. However, despite these advancements, extracting clinically meaningful information from imaging data remains challenging, particularly in detecting early-stage or subclinical myocardial abnormalities.

To address these challenges, computational methods rooted in machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have gained increasing attention for their ability to analyze complex imaging data and improve diagnostic accuracy11,12,13. These approaches have demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional statistical models. Nevertheless, their clinical application is still limited due to practical constraints, including extensive manual preprocessing requirements, high computational demands, and a lack of interpretability. Furthermore, variations in imaging protocols and inter-patient differences create additional barriers to the development of generalizable models.

Radiomics has emerged as a promising complementary technique, enabling the extraction of high-dimensional quantitative features that capture subtle tissue heterogeneity. Foundational studies by Greenspan et al.14 and Litjens et al.15 laid the groundwork for integrating deep learning into medical image analysis, with an emphasis on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for segmentation, classification, and object detection across multiple imaging domains. More recently, Zhang et al.16 highlighted the increasing utility of radiomics for high-throughput quantitative image analysis, particularly when combined with deep learning architectures. These approaches have demonstrated substantial potential in improving diagnostic performance and interpretability by capturing spatial and temporal variations in tissue characteristics. Despite these advancements, a critical limitation remains in the seamless integration of radiomic features into end-to-end deep learning pipelines. Most existing studies either apply radiomics and deep learning in parallel or post hoc, often lacking joint optimization strategies that could synergize handcrafted texture features with learned semantic representations. Furthermore, model robustness and interpretability remain key concerns, especially in the context of non-contrast cine CMR imaging, where subtle myocardial tissue changes are challenging to characterize. It highlights the need for a unified, interpretable framework that combines radiomic feature engineering with deep learning-based segmentation to enhance myocardial infarction detection in a clinically meaningful way.

In this study, we present a hybrid framework that integrates radiomic texture analysis with a deep learning-based segmentation model for improved detection of myocardial infarction using non-contrast cine CMR images. The proposed approach combines the interpretability of radiomic features with the segmentation efficiency of a modified U-Net architecture. Through early and intermediate fusion strategies, the model enables accurate differentiation between infarcted and viable myocardial tissue and demonstrates robust performance across heterogeneous datasets. This framework aims to enhance diagnostic precision and interpretability, ultimately supporting earlier and more personalized clinical decision-making in the management of myocardial infarction.

Methods

Figure 1 presents an overview of the complete workflow for the proposed MI detection and segmentation framework using CMR imaging. The methodology is structured into six principal stages: data description and augmentation, image preprocessing, radiomic feature engineering, feature selection, and model architecture and model evaluation. This structure ensures reproducibility, clinical relevance, and technical rigor.

Ethical approval

This study utilized publicly available cardiac MRI datasets: the Sunnybrook Cardiac Dataset (SCD)17 and the Kaggle Second Annual Data Science Bowl dataset18. Both datasets are anonymized and pre-approved for academic use. As no identifiable patient information was involved, further institutional ethics approval was not required. All analyses adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and applicable data governance standards.

Data description and augmentation

Dataset characteristics

The SCD dataset comprises 132 subjects (68 normal, 64 MI), each with manually annotated segmentation masks for the left ventricle. The Kaggle dataset includes 681 cine-MRI cases (301 normal, 380 MI), of which 544 are accompanied by ground-truth labels for end-systolic (ES) and end-diastolic (ED) blood volumes. The remaining 137 cases lacking such annotations were reserved for independent testing. Images from the Kaggle dataset cover both short-axis (SA) and long-axis (LA) views, with LA views encompassing a mix of two-chamber and four-chamber 2D + time sequences. Left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) views, representing less than 1% of the dataset, were excluded for consistency. The demographic composition includes 58.8% males and 41.2% females, with a mean age of 42.1 years (range: 2 weeks to 88 years).

Data augmentation techniques

To improve model generalization and mitigate overfitting, several data augmentation strategies were applied, including rotation by ± 10° to simulate orientation variability, random horizontal and vertical flipping, contrast enhancement using Contrast-Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE), and Gaussian noise injection to mimic real-world imaging artifacts. All images were resized to 128 × 128 pixels and normalized to the [0,1] range using min-max scaling. Ground-truth masks were binarized, and image–mask pairs were matched by filename. The dataset was partitioned into training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets using a fixed random seed (42) to ensure reproducibility.

Image preprocessing and feature engineering

Preprocessing and normalization

Preprocessing included CLAHE-based contrast enhancement and Gaussian filtering for denoising19. Pixel intensities were normalized as follows:

where \(\:I\) denotes the pixel value, and \(\:{I}_{min}\) and \(\:{I}_{max}\) are the minimum and maximum intensity values, respectively. Gaussian filtering20 was applied using the standard Gaussian kernel:

Where x and y are spatial coordinates, and σ is the standard deviation of the Gaussian kernel. Binary segmentation masks were obtained using a thresholding operation:

where M represents the predicted mask pixel intensity, and \(\:{M}_{binary}\) denotes the resulting binary output mask.

Radiomic feature extraction

Radiomic texture features were extracted using the Gray-Level Co-Occurrence Matrix (GLCM) and Gray-Level Run Length Matrix (GLRLM) methods. The selected descriptors included Joint Entropy, Max Probability, Sum Entropy, Joint Energy, and Run-Length Non-Uniformity (RLNU). To ensure consistent input scaling across all features, each was normalized to the [0,1] range.

Feature selection pipeline

A three-stage feature selection pipeline was implemented to identify and retain the most relevant features for myocardial tissue characterization. It included correlation filtering, statistical significance testing, and final ranking using Multi-class Support Vector Machine Recursive Feature Elimination (MSVM-RFE). This supervised technique iteratively removes the least informative features based on model weights.

These selected features are further detailed in Table 1 and offer critical insights into textural differences relevant to infarct detection:

-

1.

Correlation filtering: Features with a Pearson correlation coefficient of |r| ≥ 0.85 were deemed redundant; the less informative of each pair was discarded.

-

2.

Statistical testing: Features were tested using two-sample t-tests or Mann–Whitney U tests based on distribution normality. P-values were adjusted using the false discovery rate (FDR) method; features with q-values < 0.05 were retained.

-

3.

Recursive feature elimination: The remaining features were ranked using MSVM-RFE with a linear kernel. The top five features were selected for model training.

Model architecture and implementation

U-Net architecture and training

The segmentation model adopts a modified U-Net architecture featuring an encoder-decoder structure with skip connections. To effectively encode both spatial and semantic information, each encoder block comprises two convolutional layers, batch normalization and max pooling operations. The decoder symmetrically mirrors this structure using transposed convolutions and skip connections to recover spatial resolution. Table 2 provides a comprehensive overview of the U-Net architecture, detailing the output shape and parameter count for each layer.

Integration of radiomic features

Figure 2 illustrates the detailed architecture of the hybrid U-Net model with radiomic feature integration. Early and intermediate fusion points, radiomic feature inputs (R), and the segmentation output (S) are explicitly annotated. The bottleneck layer, representing the deepest point in the network, facilitates high-level abstraction and serves as the bridge between the encoder and decoder paths. Radiomic features were integrated into the U-Net through early and intermediate fusion. In early fusion, normalized radiomic feature maps were concatenated with the input image channels before the encoder. During intermediate fusion, these features were also concatenated at each encoder level with the corresponding learned feature maps. This dual-guided approach enhances spatial encoding and supports the detection of subtle MI patterns. Additionally, a radiomics-consistency term was incorporated into the loss function to enforce alignment between segmentation outputs and texture-based features.

Classifier comparison and ablation study

To assess radiomic-based MI classification, the following classifiers were evaluated: Random Forest (RF), Extra Trees (ET), Logistic Regression (LR), Linear and Quadratic Discriminant Analysis (LDA, QDA), AdaBoost (AB), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Naive Bayes (NB), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Multi-layer Perceptron (MLP). Hyperparameters were optimized using grid search with 5-fold cross-validation. Metrics included accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC-AUC. An ablation study evaluated the impact of data augmentation by comparing models trained with and without augmentation using the Dice coefficient, IoU, and pixel accuracy.

Model evaluation

Model performance was comprehensively assessed using a combination of segmentation, classification, and agreement metrics. Segmentation quality was evaluated using the Dice Similarity Coefficient (DSC), Intersection over Union (IoU), and the 95th percentile Hausdorff Distance (HD95). Classification effectiveness was measured by accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and the area under the ROC curve (AUC). Agreement between predicted and reference infarct areas was analyzed using Pearson correlation and Bland-Altman analysis. Additionally, visualization techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) and t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) were employed to examine feature distributions and class separability. A five-fold cross-validation strategy on the combined SCD and Kaggle dataset ensured model generalizability. Metrics were averaged across folds, and all experiments were conducted using fixed random seeds. To assess clinical relevance, model outputs were compared against cardiologist-annotated infarct regions, providing insights into the reliability of segmentation results in localizing myocardial infarctions.

Results

This section presents a structured overview of the model’s performance, encompassing radiomic feature extraction, segmentation models, classification evaluation, dimensionality reduction, and cross-validation. Quantitative metrics and visualizations are included to support the findings.

Feature extraction model

Univariate feature analysis

Radiomic analysis identified Joint Entropy as the most discriminative feature, achieving an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.948 \(\left( {p = 4.02~ \times 10^{{ - 13}} ;~q = 2.01 \times 10^{{ - 12}} } \right)\). The mean univariate AUC across all extracted features was 0.73 ± 0.08. Table 3 summarizes key radiomic features retained after correlation filtering and statistical testing. The table includes AUC, p-values, q-values, and the mean ± standard deviation for each feature across both myocardial infarction (MI) and normal classes. Joint Entropy shows the highest discriminative power with an AUC of 0.948, followed closely by Max Probability (AUC = 0.885) and RLNU (AUC = 0.857). These features exhibit statistically significant differences, with Joint Entropy values substantially elevated in infarcted myocardium (0.47 ± 0.12) compared to normal tissue (0.19 ± 0.06). The exclusion of radiomic features from the model led to a 5.7% reduction in overall classification accuracy.

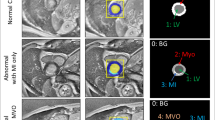

Figure 3 presents boxplots of z-score distributions for selected radiomic features, illustrating noticeable differences between infarcted and healthy myocardium. Figure 4 shows radiomic texture feature maps derived from GLCM, highlighting regional heterogeneity in myocardial tissue captured from cine-CMR images. The first column displays original cine-CMR slices for two normal subjects (Normal 1 and Normal 2) and two myocardial infarction cases (MI 1 and MI 2).

Z-score boxplot of univariate radiomic feature distributions for healthy (Normal) and infarcted (Sick) myocardium. Five texture features (Joint Entropy, Max Probability, Sum Entropy, Joint Energy, and Run-Length Non-Uniformity (RLNU)). Higher Z-scores in infarcted tissue suggest significant radiomic heterogeneity. Boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR), whiskers show 1.5×IQR, and outliers are marked as dots.

Radiomic feature maps extracted from cine-CMR slices of normal and myocardial infarction (MI) cases. Columns represent the original CMR image, followed by computed maps for Joint Entropy, Max Probability, Sum Entropy, Joint Energy, and RLNU. Rows correspond to two normal and two infarcted cases. Infarcted regions (MI 1, MI 2) exhibit elevated entropy and RLNU, indicating greater tissue complexity and heterogeneity than normal myocardium.

The subsequent columns represent corresponding radiomic maps for Joint Entropy, Max Probability (MaxPro), Sum Entropy, Joint Energy, and RLNU. Compared to normal myocardium, infarcted regions exhibit increased texture complexity, evident in the Joint Entropy and RLNU maps, reflecting greater structural irregularity in infarcted tissue. Figure 5 demonstrates the spatial correspondence between radiomic texture maps and manually annotated infarct regions on cine-CMR images for four MI cases (MI 1–MI 4). Each row displays the original CMR image, manual segmentation contours (yellow lines), segmentation output from Otsu’s thresholding method, and radiomic maps for Joint Entropy, MaxPro, Sum Entropy, Joint Energy, and RLNU. The radiomic maps reveal myocardial regions with elevated heterogeneity that broadly align with expert-defined scar zones. While these maps capture key infarcted areas, their boundaries are less sharply defined than those obtained from manual labels or traditional thresholding, illustrating the potential and current limitations of radiomics-based localization.

Multivariate feature analysis

A comparative evaluation of univariate versus multivariate radiomic feature extraction methods was conducted for MI detection. The univariate approach utilized individually discriminative texture features, while the multivariate method incorporated higher-order descriptors such as autocorrelation to capture complex spatial relationships within myocardial tissue. Table 4 presents classification metrics, including AUC, accuracy, and F1 scores across various machine learning classifiers. The multivariate feature set consistently outperformed the univariate approach, indicating enhanced predictive accuracy and robustness.

U-Net segmentation model

Figure 6 demonstrates the performance of the U-Net segmentation model in identifying MI regions on late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance (LGE-CMR) images. Each row presents an original CMR slice (left), the corresponding expert-annotated ground truth mask (middle), and the model’s predicted segmentation mask (right). The predicted masks show good alignment with the infarct morphology, successfully capturing the general shape and location of infarcted regions. However, the delineation is visibly less precise compared to manual annotations, with predicted borders appearing smoother and less localized. These differences are particularly evident in cases with subtle intensity variations between infarcted and non-infarcted myocardium, highlighting the challenges of segmenting faint or diffuse infarct zones from LGE-CMR using automated methods. The U-Net model was also evaluated for its standalone classification performance on a test set of 27 samples. It achieved an overall accuracy of 96.30%. For Class 0 (Normal), precision was 0.93 ± 0.04, recall 0.98 ± 0.01, and F1-score 0.97 ± 0.01. For Class 1 (MI), precision was 0.97 ± 0.01, recall 0.92 ± 0.04, and F1-score 0.95 ± 0.02. Macro-averaged precision, recall, and F1-score were 0.96 ± 0.01, 0.94 ± 0.03, and 0.96 ± 0.01, respectively. Weighted averages were 0.95 ± 0.02, 0.96 ± 0.04, and 0.96 ± 0.01, respectively. Table 5 presents detailed class-wise performance metrics.

Segmentation results for myocardial infarction detection using the proposed model. Each row corresponds to a different case and displays three images: the original cine-MRI image showing the myocardial infarction (left), the expert-annotated ground truth segmentation mask (middle), and the model-predicted segmentation mask (right). The model accurately identifies infarct regions; however, minor differences in boundary sharpness compared to expert annotations are observed.

Hybrid segmentation model: radiomics and U-Net integration

Radiomic features quantifying myocardial texture, intensity, and shape were incorporated into the U-Net model to improve infarct segmentation accuracy. The feature set included univariate and multivariate descriptors from GLCM and GLRLM, such as autocorrelation, cluster shade, and information correlation.

Segmentation performance of the proposed U-Net model integrated with radiomic features across four representative myocardial infarction (MI) cases. Each row corresponds to a different MI case and presents four images: the original cine-MRI slice depicting the infarcted myocardium (first column), the expert manual annotation of infarct regions shown as white masks (second column), the model-predicted infarct areas overlaid in red (third column), and the corresponding probability map indicating prediction confidence (fourth column). Warmer colors in the probability maps represent higher certainty in infarct detection, demonstrating both spatial alignment and interpretability of the model outputs.

Figure 7 illustrates the segmentation performance of the hybrid U-Net model enhanced with radiomic features. Each row presents an original LGE-CMR image (left), the corresponding ground truth mask annotated by experts (second column), the predicted segmentation mask overlaid in red (third column), and a probability map representing model confidence (rightmost column). The model incorporates radiomic descriptors such as autocorrelation, cluster shade, and information correlation extracted from GLCM and GLRLM to enrich spatial and texture-based information. The predicted masks exhibit close alignment with the reference annotations, and the probability maps indicate high confidence in infarcted regions. While minor discrepancies are visible along some borders due to subtle variations in texture and intensity, the integration of radiomic features enhances segmentation accuracy and interpretability compared to the baseline model. An ablation study evaluated the impact of data augmentation on U-Net segmentation performance. Table 6 shows that augmentation improved the Dice similarity coefficient from 0.7006 to 0.841 and the Intersection over Union (IoU) from 0.5392 to 0.729. Pixel accuracy increased from 0.9782 to 0.9814.

Building on the augmented U-Net architecture, Table 7 presents a comparison of segmentation performance between the augmented U-Net and the hybrid U-Net with integrated radiomic features. The hybrid model demonstrated improvements across all evaluation metrics, achieving a Dice score of 0.887, an Intersection over Union (IoU) of 0.803, and a reduced 95th percentile Hausdorff Distance (HD95) of 4.48 millimeters. These results indicate enhanced accuracy and spatial precision in infarct delineation when radiomic features are incorporated.

Quantitative comparison of segmentation performance between the U-Net and U-Net + Radiomics models across three evaluation metrics: Dice Similarity Coefficient (left), Jaccard Index (center), and 95th percentile Hausdorff Distance (right). Bars represent mean scores; error bars indicate standard deviation across the validation set. The hybrid model consistently outperformed the standalone U-Net, with higher overlap scores and reduced boundary error.

Figure 8 provides a visual comparison of segmentation performance between the baseline U-Net and the hybrid U-Net with radiomics integration across three key metrics: Dice score, IoU, and HD95. Each bar represents the mean value for the corresponding metric, and the error bars indicate the standard deviation observed across the validation set. The hybrid model outperforms the baseline in both overlap-based metrics (Dice and IoU) and boundary accuracy (HD95), confirming the advantage of combining deep learning with handcrafted radiomic descriptors for myocardial infarction segmentation.

Feature distribution via PCA and t-SNE

Figure 9 visualizes the distribution of radiomic features for MI and normal cases using PCA and t-SNE. The left panel (PCA) reveals partial separation between MI and normal cases. The right panel (t-SNE) demonstrates clearer class separation, indicating that nonlinear relationships in radiomic features are better captured by t-SNE. These results confirm that radiomic features offer meaningful class discrimination, although further feature refinement could enhance classification performance.

Feature space visualization using Principal Component Analysis (PCA, left) and t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE, right). Each point represents a subject, color-coded by class (blue: Normal, red: MI). PCA shows partial separation, while t-SNE reveals more apparent infarcted versus healthy sample clustering, indicating effective radiomic feature discrimination within the hybrid U-Net framework.

Evaluation of classification performance

The classification performance of the hybrid U-Net with radiomic feature integration was evaluated using multiple statistical analyses. The confusion matrix in Fig. 10 shows accurate discrimination between normal and MI cases, with only one false negative, potentially due to variations in infarct severity or image quality.

The ROC curve in Fig. 11 demonstrates excellent model discrimination, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.97, indicating strong sensitivity and specificity.

Figure 12 presents correlation and Bland-Altman analyses for infarct size quantification. The scatter plots in the top row show strong correlations between actual and predicted infarct area (r = 0.95) and infarct area percentage (r = 0.98). Regression lines are closely aligned with the identity line, indicating low systematic error. The Bland-Altman plots in the bottom row display minor mean differences and narrow 95% limits of agreement, confirming consistent prediction accuracy.

Evaluation of myocardial infarction quantification using correlation and Bland-Altman analysis. Top row: Scatter plots show high linear correlation between predicted and ground-truth infarct area (r = 0.95) and infarct percentage (r = 0.98), with near-unity regression slopes. Bottom row: Bland-Altman plots demonstrate strong agreement with low bias and tight 95% limits of agreement, confirming the accuracy and reliability of the proposed model’s infarct quantification.

To further evaluate statistical reliability, bootstrap resampling with 1000 iterations was applied to the 544 labeled cases in the Kaggle dataset. Table 8 reports an average accuracy of 96.30% and an AUC of 0.97, with narrow 95% confidence intervals across metrics, supporting the robustness and reproducibility of the proposed classification framework.

Cross-validation performance

A five-fold cross-validation was performed using the combined Sunnybrook Cardiac Dataset (SCD) and Kaggle dataset. The model achieved fold-wise classification accuracies of 96.09%, 97.47%, 98.06%, 97.13%, and 96.13%, respectively. The average accuracy across folds was 96.98% with a standard deviation of ± 0.77%, reflecting strong consistency and generalizability across varied data partitions. Figure 13 illustrates the individual fold accuracies along with the overall mean accuracy, indicated by the dashed red line.

Discussion

The detection of MI using cine-MRI has been widely investigated21,22; however, challenges remain in optimizing both segmentation accuracy and classification performance. Traditional radiomics-based approaches have demonstrated potential, but their dependence on predefined features can limit adaptability across diverse patient populations. In contrast, deep learning methods offer the ability to automatically extract relevant features, overcoming several of the limitations associated with conventional imaging analysis23. This study bridges these paradigms by comparing a deep learning-based segmentation model with radiomic feature-based classification, reinforcing the growing role of automated approaches in MI detection.

Our findings demonstrate that the deep learning model outperforms conventional radiomic models in both segmentation and classification tasks. The segmentation results show strong agreement with expert annotations, confirming the model’s ability to identify infarcted tissue accurately. Additionally, the classification model achieved an overall accuracy of 96.30%, with an AUC of 0.97, precision of 0.96, recall of 0.94, and F1-score of 0.96. These results highlight the robustness of deep learning-based solutions and align with emerging trends in radiomics-enhanced, data-driven cardiac imaging strategies.

Comparison with prior research further supports the efficacy of automated approaches for MI detection. Durmaz et al.24 integrated MRI radiomic features with clinical data, achieving a correlation coefficient of 0.965 and classification accuracy of 0.894 for predicting adverse cardiac events in STEMI patients. Al-Antari et al.25 developed a ResU-Net model for MI and microvascular obstruction segmentation, reporting an accuracy of 88.48%, recall of 85.24%, and F1-score of 85.35%, with improvements gained through contrast enhancement preprocessing. Chen et al.26 applied radiomic modeling to coronary CT angiography, attaining an AUC of 0.904 and a C-index of 0.88, highlighting radiomics’ prognostic value. Deng et al.27 used cine-CMR radiomics to differentiate ischemic from dilated cardiomyopathy, reaching a validation AUC of 0.919. Ghafari et al.28 developed an XGBoost classifier using clinical data from 1699 MI patients, achieving an AUC of 78.65%, sensitivity of 94.35%, and accuracy of 91.47%. Kar et al.29 introduced a DeepLabV3 + framework for MRI-based segmentation and strain estimation, reporting F1 and Dice scores of 0.95 and 0.96, respectively.

Table 9 provides a benchmarking comparison of the proposed framework against other recent radiomics-integrated or CNN-based approaches for MI detection. The hybrid model presented here outperforms others in both classification and segmentation metrics, attributed to its multi-level fusion strategy and the use of a radiomics-guided hybrid loss function. Unlike models that apply radiomic features retrospectively or treat them separately, our end-to-end framework enables joint optimization of both texture-based and semantic features. The inclusion of two public cine-MRI datasets and the application of targeted data augmentation further enhance the model’s robustness and generalizability.

Despite these encouraging outcomes, several limitations warrant attention. First, while the dataset size is adequate for initial validation, its relatively modest scale may affect generalizability. Future studies incorporating multi-center data would enhance external validity. Second, the current research focuses exclusively on cine-MRI, omitting other relevant imaging modalities such as late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) MRI, which may offer complementary insights for infarct characterization. Multimodal imaging integration could further improve diagnostic accuracy. Third, minor discrepancies between automated and manual infarct boundary delineations suggest that additional refinement is needed to capture subtle textural variations in myocardial tissue.

An additional concern for clinical adoption involves the reproducibility of radiomic features across different MRI systems, vendors, and acquisition protocols. Variations in hardware, magnetic field strength, pulse sequences, and reconstruction parameters can introduce scanner-specific biases that may limit model generalizability. Although this study employed publicly available datasets encompassing diverse imaging conditions, no explicit harmonization techniques (e.g., ComBat or domain adaptation) were applied. Future work should address these concerns by incorporating harmonization methods and conducting prospective multicenter validations.

Further research should also investigate the integration of clinical and biochemical markers with imaging-derived features to enhance diagnostic precision. Incorporating multimodal imaging data, including LGE-MRI and coronary CT angiography (CCTA), may provide a more comprehensive picture of myocardial health. In parallel, implementing explainable artificial intelligence (AI) techniques could improve the interpretability and clinical trustworthiness of deep learning outputs. Validation across larger and more diverse patient cohorts will be essential to ensure the clinical applicability and reliability of the proposed framework.

While this study focused on cine-MRI data, the underlying framework is readily adaptable to other cardiac imaging modalities, including LGE-MRI and CCTA. The U-Net architecture and radiomic feature pipeline are not modality-specific, as they rely on spatial texture patterns common to grayscale medical images. However, applying the model to other imaging modalities would necessitate retraining on representative datasets and adjusting feature normalization to accommodate differences in contrast dynamics, spatial resolution, and acquisition protocols. This flexibility underscores the potential of the framework for broader multimodal applications, contingent upon further validation.

Conclusion

This study presents a hybrid framework that integrates handcrafted radiomic features with deep learning-based segmentation for myocardial infarction (MI) detection using non-contrast cine cardiac MRI. By embedding radiomic descriptors into a modified U-Net architecture, the proposed approach leverages both spatial texture patterns and learned semantic representations to achieve robust and interpretable segmentation and classification of infarcted myocardial tissue.

Our results demonstrate that the combined model significantly improves segmentation accuracy compared to the baseline U-Net and achieves excellent classification performance, with an AUC of 0.97 and an overall accuracy of 96.30%. Radiomic features such as Joint Entropy and RLNU showed strong discriminative power, and feature visualization techniques confirmed the clear separation between infarcted and healthy tissues. Correlation and Bland-Altman analyses further validated the model’s reliability in infarct quantification.

The proposed framework offers a promising direction for non-invasive, label-efficient myocardial tissue characterization, especially in scenarios where contrast agents are contraindicated. Future research should explore the extension of this framework to multi-modality imaging, clinical data integration, and feature harmonization across different imaging protocols to enhance generalizability and clinical adoption.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in publicly accessible repositories. The Sunnybrook Cardiac Dataset (SCD) is available at https://www.cardiacatlas.org/sunnybrook-cardiac-data/, and the Kaggle Second Annual Data Science Bowl dataset is available at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/adarshsng/heart-mri-image-dataset-left-atrial-segmentation/data.

References

Baessler, B. et al. Subacute and chronic left ventricular myocardial scar: accuracy of texture analysis on nonenhanced cine MR images. Radiology 286 (1), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2017170213 (2018).

Zhou, H. et al. Protective role of melatonin in cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury: from pathogenesis to targeted therapy. J. Pineal Res. 64 (3), e12471. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12471 (2018).

Maadani, M. et al. Relationship between preprocedural lipid levels and periprocedural myocardial injury in patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 49 (6), e207384. https://doi.org/10.14503/THIJ-20-7384 (2022).

Jernberg, T. et al. Cardiovascular risk in post-myocardial infarction patients: nationwide real world data demonstrate the importance of a long-term perspective. Eur. Heart J. 36 (19), 1163–1170. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehu505 (2015).

Dehkharghani, M. Z. et al. Importance of long non-coding RNAs in the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of myocardial infarction. IJC Heart Vasculature. 55, 101529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcha.2024.101529 (2024).

Himmelreich, J. C. et al. Prediction models for atrial fibrillation applicable in the community: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EP Europace. 22 (5), 684–694. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euaa005 (2020).

Qiang, Y., Dong, X. & Yang, Y. Automatic detection and localisation of myocardial infarction using multi-channel dense attention neural network. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 89, 105766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105766 (2024).

Dewey, M. et al. Clinical quantitative cardiac imaging for the assessment of myocardial ischaemia. Nat. Reviews Cardiol. 17 (7), 427–450 (2020).

Schulz-Menger, J. et al. Standardized image interpretation and post-processing in cardiovascular magnetic resonance-2020 update: society for cardiovascular magnetic resonance (SCMR): board of trustees task force on standardized post-processing. J. Cardiovasc. Magnetic Resonance. 22 (1) 19. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12968-020-00610-6

Martins-Marques, T., Hausenloy, D. J., Sluijter, J. P., Leybaert, L. & Girao, H. Intercellular communication in the heart: therapeutic opportunities for cardiac ischemia. Trends Mol. Med. 27 (3), 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2020.10.002 (2021).

Sridhar, C. et al. Accurate detection of myocardial infarction using non linear features with ECG signals. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 3227–3244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12652-020-02536-4 (2021).

Degerli, A. et al. Early detection of myocardial infarction in low-quality echocardiography. IEEE Access. 9, 34442–34453. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3059595 (2021).

Jahmunah, V., Ng, E. Y., Tan, R. S., Oh, S. L. & Acharya, U. R. Explainable detection of myocardial infarction using deep learning models with Grad-CAM technique on ECG signals. Comput. Biol. Med. 146, 105550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2022.105550 (2022).

Greenspan, H., Van Ginneken, B. & Summers, R. M. Guest editorial deep learning in medical imaging: overview and future promise of an exciting new technique. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 35 (5), 1153–1159. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2016.2553401 (2016).

Litjens, G. et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med. Image. Anal. 42, 60–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.media.2017.07.005 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. Deep learning with radiomics for disease diagnosis and treatment: challenges and potential. Front. Oncol. 12 (773840). https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2022.773840 (2022).

Radau, P. et al. Sunnybrook cardiac data. sunnybrook health sciences centre; (2009). Available from: http://www.cardiacatlas.org/challenges/sunnybrook-cardiac-data/

Second annual data science bowl. kaggle. https://www.kaggle.com/c/second-annual-data-science-bowl

Liu, X. & Nguyen, T. D. Medical images enhancement by integrating CLAHE with wavelet transform and non-local means denoising. Acad. J. Comput. Inform. Sci. 7 (1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.25236/AJCIS.2024.070108 (2024).

Shin, D. H., Park, R. H., Yang, S. & Jung, J. H. Block-based noise estimation using adaptive Gaussian filtering. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 51 (1), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCE.2005.1405723 (2005).

Zhang, N. et al. Deep learning for diagnosis of chronic myocardial infarction on nonenhanced cardiac cine MRI. Radiology 291 (3), 606–617. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2019182304 (2019).

Polacin, M. et al. Segmental strain analysis for the detection of chronic ischemic scars in non-contrast cardiac MRI cine images. Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 12376. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-90283-7 (2021).

Radwa, E., Ridha, H. & Faycal, B. Deep learning-based approaches for myocardial infarction detection: A comprehensive review recent advances and emerging challenges. Med. Novel Technol. Devices. 100322 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medntd.2024.100322 (2024).

Durmaz, E. S. et al. Radiomics-based machine learning models in STEMI: a promising tool for the prediction of major adverse cardiac events. Eur. Radiol. 33 (7), 4611–4620. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-023-09394-6 (2023).

Al-antari, M. A. et al. Deep learning myocardial infarction segmentation framework from cardiac magnetic resonance images. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 89, 105710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2023.105710 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. A coronary CT angiography-derived myocardial radiomics model for predicting adverse outcomes in chronic myocardial infarction. Int. J. Cardiol. 132265 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2024.132265 (2024).

Deng, J. et al. Integration of cine-cardiac magnetic resonance radiomics and machine learning for differentiating ischemic and dilated cardiomyopathy. Acad. Radiol. 31 (7), 2704–2714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2024.03.032 (2024).

Ghafari, R. et al. Prediction of the fatal acute complications of myocardial infarction via machine learning algorithms. J. Tehran Univ. Heart Cent. 18 (4), 278. https://doi.org/10.18502/jthc.v18i4.14827 (2023).

Kar, J., Cohen, M. V., McQuiston, S. A., Poorsala, T. & Malozzi, C. M. Direct left-ventricular global longitudinal strain (GLS) computation with a fully convolutional network. J. Biomech. 130, 110878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2021.110878 (2022).

Larroza, A. et al. Texture analysis of cardiac cine magnetic resonance imaging to detect nonviable segments in patients with chronic myocardial infarction. Med. Phys. 45 (4), 1471–1480. https://doi.org/10.1002/mp.12783 (2018).

Pu, C. et al. Identification of fibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a radiomic study on cardiac magnetic resonance cine imaging. Eur. Radiol. 33 (4), 2301–2311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-022-09217-0 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: (Wang Xu)Methodology: (Wang Xu and Xiangjiang Shi)Software: (Wang Xu)Validation: (Xiangjiang Shi)Formal analysis: (Wang Xu and Xiangjiang Shi)Investigation: (Xiangjiang Shi)Resources: (Wang Xu and Xiangjiang Shi)Data curation: (Wang Xu and Xiangjiang Shi)Writing—original draft preparation: (Wang Xu)Writing—review and editing: (Xiangjiang Shi)Visualization: (Wang Xu)Supervision: (Xiangjiang Shi)Project administration: (Wang Xu)

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

This study utilized the Sunnybrook Cardiac Dataset (SCD) and the Kaggle Second Annual Data Science Bowl dataset, the publicly available and fully anonymized datasets containing CMR images. All participants provided informed consent as part of the original data collection process. No additional consent was required for this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, W., Shi, X. Integrating radiomic texture analysis and deep learning for automated myocardial infarction detection in cine-MRI. Sci Rep 15, 24365 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08127-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08127-7