Abstract

Despite advancements in treatment, the overall mortality rate among critically ill coronary artery disease (CAD) patients remains high. The impact of blood pressure variability (BPV) on these patients remains controversial. This study investigates the relationship between 24-hour BPV and mortality in critically ill CAD patients in the ICU. A retrospective analysis was conducted on CAD patients admitted to the ICU from 2008 to 2019 using the MIMIC-IV database. BPV was assessed by calculating average real variability (ARV) during the first 24 h of ICU admission, classifying patients into low, medium, and high ARV groups. Endpoints included in-hospital and 1-year mortality, analyzed using logistic regression, Cox proportional hazards regression, and restricted cubic splines. A total of 4,588 CAD patients were included. ARV of diastolic blood pressure (DBP) was positively correlated with 1-year mortality (HR 1.03, 95% CI 1.00-1.06), independent of other factors. ARVof systolic blood pressure (SBP) showed a U-shaped relationship with 1-year mortality; values below 16.912 mmHg reduced risk (HR 0.956, 95% CI 0.924–0.988), while higher values increased risk (HR 1.180, 95% CI 1.044–1.333). No significant associations were found with short-term mortality. In critically ill CAD patients, 24-hour ARV of DBP and SBP show significant associations with 1-year mortality. Elevated DBP variability is associated with increased risk, while SBP variability demonstrates a U-shaped association, suggesting both very low and very high SBP variability are detrimental. These findings highlight the potential importance of monitoring BPV to identify high-risk patients and suggest that targeted BP management strategies, considering variability, may improve long-term outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a leading cause of death worldwide, significantly impacting both developed and developing nations1,2,3,4,5. Despite advancements in treatments such as aspirin, statins, and percutaneous coronary intervention, mortality is particularly high among critically ill CAD patients in the ICU, who often present with poor baseline health and rapid disease progression, leading to a 1-year mortality rate of up to 16.1%6,7,8. While CAD ranks as the second leading cause of death worldwide, after malignant tumors9,10research specifically focused on optimizing prognostic management for this critically ill subpopulation remains limited.

Blood pressure variability (BPV), the fluctuation of blood pressure(BP) over time, is influenced by hemodynamics, neurohumoral regulation, behavior, and environment11,12,13,14,15,16. These fluctuations, beyond absolute BP values, can damage coronary arteries and increase cardiac load and oxygen demand, negatively impacting cardiac prognosis17,18. Studies have shown a strong link between elevated BPV and cardiovascular events19,20,21,22,23,24.Studies in ICU patients link increased BPV to higher mortality, prolonged ICU stays, and organ dysfunction. However, existing ICU BPV research has limitations: small sample sizes, specific subpopulations, and inconsistent BPV metrics23,25,26. This heterogeneity hinders firm conclusions about optimal BPV measurement and its prognostic value across the broader ICU population, especially concerning whether increased BPV directly leads to poor outcomes23,25.

The impact of BPV on outcomes in critically ill patients with coronary artery disease is particularly understudied. Existing CAD research often focuses on ambulatory monitoring in non-critically ill individuals16,17neglecting the unique physiological challenges and interventions in the ICU (e.g., vasopressors, mechanical ventilation), which can significantly influence BPV. Therefore, findings from ambulatory settings may not be directly applicable to critically ill patients. While traditional metrics for assessing BPV, such as standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV), primarily focus on the overall spread of BP values, they do not capture the sequential nature of BP fluctuations. To address this, newer metrics like average real variability (ARV) have emerged. ARV offers a more reliable assessment by considering the temporal dynamics of BP changes and is less affected by outliers, making it particularly suitable for ICU settings27,28. This study seeks to refine the assessment of BPV’s prognostic significance in critically ill patients with CAD by examining the association between 24-hour ARV and mortality.

Methods

Database

This study is based on the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV (MIMIC-IV) version 2.2 database, which supports a retrospective cohort analysis. The MIMIC-IV database contains clinical data from over 50,000 patients admitted to Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center from 2008 to 2019. It provides extensive, real-world clinical data encompassing vital signs, laboratory test results, medication records, diagnosis codes, imaging reports, prognosis, and other pertinent information relevant to ICU patients in a tertiary care setting. Data extraction and processing were conducted using Structured Query Language to facilitate subsequent analysis. All researchers involved in this study completed relevant training courses provided by the National Institutes of Health and successfully passed necessary assessments to gain access to the MIMIC-IV database (certificate number: 52898099). In this research, we utilized version 2.2 of the database and employed PostgreSQL v13.0 for data retrieval (http://www.postgresql.org/). As all personal data in the database has been deidentified before analysis, the requirement for institutional review board approval was waived, and patient consent was not required29,30.

Study populations

This study extracted patient data from the MIMIC-IV version 2.2 database. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows:

Inclusion Criteria:

-

(1)

Patients were included if they had the history of CAD. The diagnosis of CAD was based on ICD-9 and ICD-10(Supplementary Table S1).

-

(2)

Age ≥ 18 years.

-

(3)

First admission to the ICU.

Exclusion Criteria:

-

(1)

ICU stay of less than 24 h.

-

(2)

Continuous BP measurements with intervals exceeding 1 h during the ICU stay, or fewer than 24 recorded BP measurements.

-

(3)

SBP < 0 mmHg or > 400 mmHg, or DBP < 0 mmHg or > 300 mmHg.

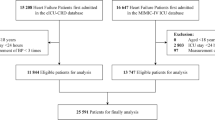

Based on these criteria, a total of 4588 CAD patients who were initially admitted to the ICU between 2008 and 2019 were included in this study.

Data extractions

This study utilized PostgreSQL and Navicat Premium 16 software for data extraction, acquiring the necessary information through Structured Query Language.

BP measurements were a crucial component of this study. All BP measurements were obtained via continuous intra-arterial monitoring recorded in the MIMIC-IV database. SBP values were identified by itemid 220,050, and DBP values by itemid 220,051.

Drawing from previous literature19,20,23,24,25,27,31,32,33 and clinical significance, the study incorporated the following potential confounding variables:

-

Baseline demographic information: age and gender.

-

Mean vital signs within the first 24 h after ICU admission: heart rate, mean arterial pressure, and respiratory rate.

-

Laboratory parameters measured included white blood cells (WBC), hemoglobin (HGB), platelets (PLT), and blood creatinine.

-

Disease states: myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, chronic lung disease, hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, sepsis, peptic ulcer disease.

-

Severity of illness scoring: Simplified Acute Physiology Score II (SAPS II).

-

Treatment measures: including the use of invasive mechanical ventilation within the first 24 h after ICU admission34administration of vasopressors and positive inotropic agents (dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, dobutamine, vasopressin, dobutamine, and milrinone), use of antihypertensive medications (including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, α receptor blockers, β receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics), implementation of antiplatelet therapy, and administration of statins.

Definition of BPV and ARV

BPV refers to the fluctuations in BP over time, reflecting the complex interplay of various physiological regulatory mechanisms. While traditionally assessed using metrics like SD and CV, these measures have limitations. SD quantifies the dispersion of BP values around the mean but ignores the temporal sequence of these values. CV, calculated as the SD divided by the mean, provides a relative measure of variability, but it also fails to account for the order of BP readings. To evaluate the dynamic changes in clinical signs and to provide a more reliable measure of BPV over time, this study employs average real variability to assess BPV during the first 24 h after patients are admitted to the ICU. The calculation formula is as follows:

where N represents the number of valid BP measurements and k represents the order of measurements27,28.ARV, a newer BPV metric, overcomes these limitations. ARV is calculated as the average absolute difference between successive BP measurements. This crucial distinction allows ARV to capture the time-dependent nature of BP fluctuations, differentiating between BP sequences with identical SD or CV values but different patterns of oscillation. For instance, two patients could have the same SD of BP, but one might have frequent, rapid fluctuations while the other has slow, gradual changes; ARV would be higher in the former case. Furthermore, ARV is less sensitive to outliers and variations in sampling frequency compared to SD and CV, making it a more robust and reliable indicator of BPV.Based on the clinical data from all patients involved in this research, the ARV of SBP (ARV-SBP) and the ARV of DBP (ARV-DBP) were calculated.

To further provide a comprehensive account of our investigations into different blood pressure variability parameters, Average Real Variability of Mean Blood Pressure (ARV-MBP) was also calculated. The detailed analysis and results for ARV-MBP are provided in the Supplementary Table S2.

Study endpoint

The primary endpoint for this study was one-year mortality following ICU admission. The date of death, used to determine one-year mortality, was obtained from the “dod” (date of death) column in the “patients” table of the MIMIC-IV database, which is based on hospital and state records. All patients were followed up for one year to ascertain this primary outcome.In-hospital mortality was evaluated as a secondary endpoint. Information regarding in-hospital mortality was derived from the “hospital expire flag” column in the “admissions” table of the MIMIC-IV database.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using R software (version 4.1.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; https://www.r-project.org). The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Results indicated that all continuous variables deviated from a normal distribution(p < 0.05). Therefore, non-parametric tests were employed throughout the analysis. Descriptive statistics included reporting the median and interquartile range (IQR) for all continuous variables. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages. The Kruskal-Wallis H test, a non-parametric equivalent of one-way ANOVA, was used to compare continuous variables across the three groups, while Fisher’s exact test was utilized for comparing categorical variables. Based on the distributions of ARV-SBP and ARV-DBP, low, medium and high tertiles groups were created (SBP-ARV: <9.86, 9.86–12.69, > 12.69;ARV-DBP<5.28, 5.28–7.07, > 7.07); We selected these confounders on the basis of judgment, previous scientific literature19,20,23,24,25,27,31,32,33. Multicollinearity was tested using the variance inflation factor (VIF) method, with a VIF ≥ 5 indicating the presence of multicollinearity. To assess associations of ARV with short-term and long-term mortality respectively, multivariable logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards regression analyses were performed. ARV was entered as a categorical variable (tertiles) and as a continuous variable. Analyses were first performed in a crude mode l (model 1: adjusted for age, sex and vital signs). Further analyses cumulatively included adjustment for laboratory parameters, disease states, disease severity scores (model 2), and treatment measures (model 3).We conducted restricted cubic spline model to develop smooth curves to examine the possible nonlinear dose-response associations between ARV and mortality. In this model, ARV was used as a continuous variable with four knots (5th, 35th, 65th and 95th) suggested by Harrell. Non-linearity tested by using a likelihood ratio test comparing the model with only a linear term against the model with linear and cubic spline terms. If a non-linear correlation was observed, a two-piecewise regression model was performed to calculate the threshold effect of ARV on mortality in terms of the smoothing plot35. Missing data comprised less than 5% of the dataset, and we dealt with missing data by listwise deletion on an analytical basis. We performed a series of model adjustments to assess the robustness of the findings. We report and compare effect sizes and p-values calculated by all these models. Two-sided p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Population characteristics

Figure 1 delineates the process of cohort selection. A total of 9,582 patients with coronary artery disease were screened from the MIMIC-IV 2.2 database and 4,994 patients were subsequently excluded based on the study criteria, resulting in a final study population of 4,588 patients.

Table 2 summarizes the fundamental characteristics of the study population. Among the participants, 82.3% are over 60 years of age, with 1,232 individuals (26.9%) being female. Moreover, 68.7% of patients received treatment with vasopressors and positive inotropic agents on the first day of ICU admission, while 71.5% received antihypertensive medication on that same day, with additional details on in-hospital and 1-year survival provided in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4.

The study categorized patients into three equal groups (low, medium and high) based on the distribution of ARV-SBP and ARV-DBP measured within 24 h of admission (ARV-SBP: <9.86, 9.86–12.69, > 12.69; ARV-DBP: <5.28, 5.28–7.07, > 7.07). Overall, the baseline characteristics across the different groups are comparable; however, significant differences exist between the SBP and DBP groups regarding gender, the presence of myocardial infarction and heart failure, the administration of vasopressors and positive inotropic agents, and the need for invasive mechanical ventilation (Table 1). Additionally, the SBP group shows significant differences in age, as well as the prevalence of diabetes and hypertension, whereas the DBP group exhibits notable differences in the utilization of antiplatelet agents and statins. Detailed baseline characteristics have been moved to Supplementary Table S5. The follow-up of 4,588 critically ill patients with coronary artery disease revealed that 208 individuals (4.5%) died during hospitalization, and 570 individuals (12.4%) succumbed within one year of admission. These findings indicate that the mortality rate among critically ill patients with coronary artery disease remains notably high.

Relationship between ARV and short-term mortality in patients with CAD

The overall in-hospital mortality rate among patients was 4.5%. In the ARV-DBP tertile groups, in-hospital mortality increased with higher tertiles, rising from 3.6% in the low tertile to 6.1% in the high tertile. In the multivariable logistic regression analysis of ARV-DBP tertiles, compared with the low tertile, the in-hospital mortality risk increased by 80% in the high tertile (OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.28–2.54, P = 0.001), but after adjusting for confounding factors, this association was no longer significant. In the multivariable logistic regression analysis with ARV-DBP as a continuous variable, an increase in ARV-DBP was positively associated with in-hospital mortality. However, after further adjustment, this association disappeared. In contrast, no significant association was observed between ARV-SBP and in-hospital mortality. After adjusting for potential confounders, no significant differences were observed when ARV-SBP was analyzed as either a continuous or categorical variable (Table 3).

Relationship between ARV and long-term mortality in patients with CAD

A long-term mortality assessment indicated an overall mortality rate of 12.4% within one year. The univariate analysis demonstrated a significant association between ARV-DBP and long-term prognosis. In the Cox regression analysis categorized by tertiles, patients in the high ARV-DBP group exhibited a 1.97-fold increased risk of death within one year compared to those in the low ARV-DBP group. This association remained significant after adjusting for potential confounding factors (HR 1.26, 95% CI 1.01–1.56, P = 0.037, Table 2, Model 3). Treating ARV-DBP as a continuous variable in the Cox regression analysis revealed that each unit increase in ARV-DBP was associated with a 14% rise in the risk of death. This relationship persisted as significant after controlling for confounding factors. The multivariable-adjusted restricted cubic spline curve illustrating the relationship between ARV-DBP and one-year mortality is presented in Fig. 2(A).The curves in particular underscore the relationship between ARV-DBP and risk ratios showed a generally positive correlation (P for non-linearity = 0.85), with an increasing trend in 1-year mortality with increasing DBP fluctuations.

In the analysis of tertiles of ARV-SBP, the reduction in 1-year mortality rate for the medium variability group compared to the low variability group is statistically significant (Table 3). Although this reduction did not show a significant association with the high variability group, the notable difference in the medium variability group suggests a potential nonlinear relationship between SBP variability and 1-year mortality rate. To further investigate this hypothesis, we utilized a restricted cubic spline nonlinear model to more accurately capture the possible nonlinear trend between SBP variability and mortality risk. Figure 2(B) illustrates that, after adjusting for potential confounding factors, there is a U-shaped nonlinear relationship between ARV-SBP and 1-year mortality rate, indicating that both excessively low and high SBP variability can increase mortality risk. The inflection point of this relationship is at an ARV-SBP value of 16.912. When ARV-SBP falls below 16.912, each 1-unit increase in ARV-SBP correlates negatively with the one-year mortality risk, suggesting that increased BP variability at lower levels may confer some protective benefits. Conversely, when ARV-SBP exceeds 16.912, the one-year mortality risk rises significantly with increased SBP variability (Table 4).

Data were fit by a Cox proportional hazard regression model based on restricted cubic splines. ARV was entered as continuous variable. Data were adjusted for gender, age, vital signs, Laboratory measurements, comorbidities, severity of illness scoring, and treatment (Model 3).The median ARV was defined as the reference standard. The red area represents the 95% CI.

Discussion

In 4,588 critically ill CAD patients, this study found that 24-hour ARV-DBP positively correlated with 1-year mortality, independently of confounders. ARV-SBP showed a U-shaped relationship with 1-year mortality (nadir at 16.912 mmHg). Neither ARV-DBP nor ARV-SBP was significantly linked to in-hospital mortality after adjustment.

While prior BPV research often focused on hypertensive populations, recent studies link BPV to adverse outcomes in non-hypertensive individuals36,37,38,39,40including increased myocardial infarction and mortality risk in the elderly41. However, Harefa et al.42 found no significant ARV-BPV link to in-hospital events in acute myocardial infarction patients, potentially due to smaller samples or different BPV metrics. Critically ill CAD patients present unique challenges due to dynamic physiological changes and intensive interventions impacting BPV, differentiating them from general or hypertensive populations and warranting specific investigation.

Comparing our findings with studies also using the MIMIC-IV database, He et al.25 found higher systolic BPV increased mortality in critically ill CAD patients. Our study, employing ARV to better capture temporal BP dynamics, aligns on the importance of BPV for long-term risk but differs in specific associations and metrics. Liu et al.23 reported no significant ARV-DBP link to short or long-term mortality in ICU patients with acute MI, contrasting with our finding of a positive correlation between ARV-DBP and 1-year mortality in a broader critically ill CAD cohort. These discrepancies may stem from our larger sample, broader patient population, the use of ARV, and more extensive adjustments for ICU-specific treatments (e.g., vasoactive drugs, antihypertensives, statins), which significantly influence BPV and outcomes.

The seemingly paradoxical finding of a significant association between 24-hour BPV and 1-year mortality, but not in-hospital mortality, warrants careful consideration. Several potential, non-mutually exclusive explanations may account for this apparent discrepancy. Firstly, the intensive in-hospital management of critically ill patients within the ICU environment, characterized by continuous monitoring and aggressive interventions such as fluid resuscitation, vasopressor administration, mechanical ventilation, and rapid antihypertensive titration, can substantially alter BP dynamics. These interventions, while crucial for immediate stabilization, may effectively mask the immediate influence of baseline BPV on short-term outcomes26. Secondly, it is plausible that the initial 24-hour BPV serves as an indicator of underlying vascular and autonomic dysregulation, reflecting a pre-existing vulnerability that manifests its prognostic significance over a longer timeframe43,44. The mechanisms through which BPV contributes to cardiovascular damage, including endothelial dysfunction and the progression of atherosclerosis, are likely to exert their influence more prominently in the long term. Thirdly, the acute and dominant drivers of in-hospital mortality in critically ill CAD patients, such as sepsis, heart failure, or cerebrovascular disease, could effectively overshadow the more subtle contribution of BPV to short-term mortality. In essence, the signal of BPV’s impact on in-hospital mortality may be obscured by the noise of these more immediate and potent factors. Furthermore, the inherent heterogeneity of our critically ill CAD patient population, despite adjustments for confounders, may introduce variability that obscures a clear short-term association. Residual confounding cannot be entirely excluded. Finally, while our sample size is considerable, it is possible that the statistical power was insufficient to detect a potentially smaller effect of BPV on the less frequent event of in-hospital mortality, compared to one-year mortality. These factors collectively suggest that while intensive care may mitigate the immediate mortality risk associated with BPV, its prognostic significance for longer-term outcomes, reflecting deeper vascular pathophysiology, remains evident. Further research specifically designed to investigate the nuanced relationship between BPV and short-term mortality in critically ill patients is warranted.

Adjusted analyses revealed a U-shaped nonlinear relationship between ARV-SBP and 1-year mortality. Risk decreased with ARV-SBP up to 16.912 mmHg, then significantly increased above this threshold, suggesting dual mechanisms impacting long-term prognosis. Below this inflection point, moderate ARV-SBP—potentially reflecting physiological regulation, stable organ perfusion, or even beneficial effects of timely vasoactive therapy—was associated with lower mortality. Conversely, very low variability might indicate autonomic dysfunction43,44. Above this threshold, excessive ARV-SBP likely signifies disrupted cardiovascular autonomic regulation, hemodynamic instability, increased cardiac workload, and underlying vascular impairment, leading to higher mortality.

To provide a more comprehensive assessment, we also investigated the ARV-MBP, with detailed results presented in Supplementary Table S2. ARV-MBP showed no independent association with 1-year mortality after full multivariable adjustment. The absence of this association is notable. We posit this notable discrepancy stems from two factors. From an intrinsic perspective, MBP is a calculated parameter. The process of combining SBP and DBP into MBP might attenuate the specific prognostic information carried by the variability of SBP and DBP components individually. SBP variability primarily relates to arterial stiffness and cardiac output fluctuations17,45,46while DBP variability is more sensitive to changes in vascular tone and diastolic coronary perfusion time17,47,48. Therefore, the combining process risks obscuring the specific insights offered by each of these unique pathophysiological mechanisms. Furthermore, a external confounder is goal-directed therapy in the ICU. Clinicians frequently target a specific MBP level when titrating vasopressors, and this continuous intervention may artificially suppress the natural variability of MBP, thereby confounding its value as an intrinsic physiological marker. As the prognostic signal of MBP may be doubly attenuated by both its mathematical derivation and clinical interventions, we conclude that in our cohort of critically ill patients with CAD, the variabilities of the component pressures (SBP and DBP) are more robust and specific long-term prognostic markers than the composite MBP. However, it is crucial to emphasize that these findings pertain to the prognostic limitations of MBP variability and do not diminish the established clinical importance of monitoring the absolute MBP level to guide hemodynamic management and ensure adequate organ perfusion. Moreover, the definitive prognostic significance of ARV-MBP in this population warrants further investigation through studies with higher levels of evidence.

Determining the optimal BPV range in critically ill CAD patients is challenging. Putative mechanisms for BPV-induced cardiovascular target organ damage include direct endothelial injury from perfusion pressure changes49renin-angiotensin system activation promoting vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and hypertrophy50worsened myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury inducing cardiomyocyte apoptosis51,52and systemic inflammatory responses53. Ultimately, these can lead to endothelial dysfunction54atherosclerosis development, cardiac remodeling, and impaired diastolic and systolic functions, thereby heightening adverse cardiovascular event risk55,56.

Our findings underscore that BP stability, particularly minimizing ARV-DBP fluctuations, is critical for the long-term prognosis of critically ill CAD patients. Clinically, while moderate ARV-SBP may be beneficial, excessive fluctuations significantly increase mortality risk. Therefore, maintaining moderate BPV while avoiding excessive fluctuations, guided by close BP monitoring and precise control, is vital for improving long-term survival rates in this vulnerable population.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, reliance on continuous intra-arterial BP monitoring, while precise for capturing BPV in critically ill patients, limits direct generalizability to non-ICU settings where non-invasive cuff-based measurements are standard and carries inherent risks57. Secondly, the potential impact of the data’s age and the evolution of medical practices on our findings, as data were collected over an extended period, which may be influenced by evolving medical practices and device updates. This is compounded by the constraint imposed by data de-identification in MIMIC-IV, which prevents detailed analysis stratified by precise patient inclusion periods. Thirdly, due to incomplete information in the database, some potential confounding factors (e.g., echocardiographic results, troponin levels, myocardial enzyme profiles) could not be analyzed. Finally, the applicability of these findings to general ward patients warrants further investigation.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that 24-hour BPV, measured by ARV, show significant associations with 1-year mortality in critically ill CAD patients. Elevated ARV-DBP independently predicts increased mortality, while ARV-SBP exhibits a U-shaped relationship, with a nadir at 16.912 mmHg, suggesting an optimal range for systolic variability. These findings highlight the prognostic value of BPV and suggest that minimizing diastolic fluctuations and targeting moderate systolic variability may improve long-term outcomes. Further prospective studies are needed to validate these findings and evaluate BPV-targeted interventions.

Data availability

The data supporting this study are publicly available in the PhysioNet repository under the MIMIC-IV project (version 2.2). The dataset can be accessed at: https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/2.2/.

References

Álvarez-Álvarez, M. M., Zanetti, D., Carreras-Torres, R., Moral, P. & Athanasiadis, G. A survey of sub-Saharan gene flow into the mediterranean at risk loci for coronary artery disease. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. EJHG. 25, 472–476 (2017).

Gupta, R., Guptha, S., Sharma, K. K., Gupta, A. & Deedwania, P. Regional variations in cardiovascular risk factors in india: India heart watch. World J. Cardiol. 4, 112–120 (2012).

Steg, P. G. et al. One-year cardiovascular event rates in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA 297, 1197–1206 (2007).

Lloyd-Jones, D. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2009 update: a report from the American heart association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation 119, 480–486 (2009).

GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and National age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet Lond. Engl. 385, 117–171 (2015).

Bhatt, D. L., Lopes, R. D. & Harrington, R. A. Diagnosis and treatment of acute coronary syndromes: A review. JAMA 327, 662–675 (2022).

Collaborative overview of. Randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy–III: reduction in venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism by antiplatelet prophylaxis among surgical and medical patients. Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collab. BMJ. 308, 235–246 (1994).

Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering. In 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin survival study (4S). Lancet Lond. Engl. 344, (1994).

Viktoria, D. M. et al. Causes of death and determinants of outcome in critically ill patients. Crit. Care Lond. Engl. 10, (2006).

Weiran, L., Lixue, C. & Chuan, W. Low body temperature and mortality in critically ill patients with coronary heart disease: a retrospective analysis from MIMIC-IV database. Eur. J. Med. Res. 28, (2023).

Elghozi, J. L., Laude, D. & Girard, A. Effects of respiration on blood pressure and heart rate variability in humans. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 18, 735–742 (1991).

Mancia, G., Grassi, G., Giannattasio, C. & Seravalle, G. Sympathetic activation in the pathogenesis of hypertension and progression of organ damage. Hypertens. Dallas Tex. 1979. 34, 724–728 (1999).

Mancia, G. et al. Arterial baroreflexes and blood pressure and heart rate variabilities in humans. Hypertens. Dallas Tex. 1979. 8, 147–153 (1986).

Narkiewicz, K. et al. Relationship between muscle sympathetic nerve activity and diurnal blood pressure profile. Hypertens. Dallas Tex. 1979. 39, 168–172 (2002).

Parati, G., Saul, J. P., Di Rienzo, M. & Mancia, G. Spectral analysis of blood pressure and heart rate variability in evaluating cardiovascular regulation. A critical appraisal. Hypertens. Dallas Tex. 1979. 25, 1276–1286 (1995).

Parati, G., Ochoa, J. E., Lombardi, C. & Bilo, G. Assessment and management of blood-pressure variability. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 10, 143–155 (2013).

Parati, G., Stergiou, G. S., Dolan, E. & Bilo, G. Blood pressure variability: clinical relevance and application. J. Clin. Hypertens. 20, 1133–1137 (2018).

Wang, Y. et al. High shear stress induces atherosclerotic vulnerable plaque formation through angiogenesis. Regen Biomater. 3, 257–267 (2016).

Frattola, A., Parati, G., Cuspidi, C., Albini, F. & Mancia, G. Prognostic value of 24-hour blood pressure variability. J. Hypertens. 11, 1133–1137 (1993).

Parati, G., Pomidossi, G., Albini, F., Malaspina, D. & Mancia, G. Relationship of 24-hour blood pressure mean and variability to severity of target-organ damage in hypertension. J. Hypertens. 5, 93–98 (1987).

Grzegorz, B. et al. The impact of systolic and diastolic blood pressure variability on mortality is age dependent: data from the Dublin outcome study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 27, (2020).

Kikuya, M. et al. Prognostic significance of blood pressure and heart rate variabilities: the Ohasama study. Hypertens. Dallas Tex. 1979. 36, 901–906 (2000).

Liu, Y. et al. Relationship between 24 h blood pressure variability and mortality in acute myocardial infarction patients. Clin. Cardiol. 47, e24261 (2024).

Palatini, P. et al. Short-term blood pressure variability outweighs average 24-h blood pressure in the prediction of cardiovascular events in hypertension of the young. J. Hypertens. 37, 1419–1426 (2019).

He, H. M. et al. Associations of variability in blood glucose and systolic blood pressure with mortality in patients with coronary artery disease: A retrospective cohort study from the MIMIC-IV database. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 209, 111595 (2024).

Hou, C., Wang, X., Li, Y. & Hei, F. The relationship between Short-Term mean arterial pressure variability and mortality in critically ill patients. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 870711 (2022).

Mena, L. J., Felix, V. G., Melgarejo, J. D. & Maestre, G. E. 24-Hour blood pressure variability assessed by average real variability: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6, e006895 (2017).

Mena, L. et al. A reliable index for the prognostic significance of blood pressure variability. J. Hypertens. 23, 505–511 (2005).

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data. 10, 1 (2023).

Giesa, N. et al. MIMIC-IV as a clinical data schema. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 294, 559–560 (2022).

Dai, L. et al. Association of visit-to-visit blood pressure variability with the risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in general population. J. Clin. Hypertens. Greenwich Conn. 20, 280–288 (2018).

Wei, X. et al. Risk analysis of the association between different hemoglobin glycation index and poor prognosis in critical patients with coronary heart disease-A study based on the MIMIC-IV database. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23, 113 (2024).

Verdecchia, P. et al. Prognostic significance of blood pressure variability in essential hypertension. Blood Press. Monit. 1, (1996).

Qu, J., Shen, Y. & Zhang, H. Early intubation and patient-centered outcomes in septic shock. Crit. Care Lond. Engl. 26, 299 (2022).

Frank, E. H. Regression Modeling Strategies: with Applications To Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis (Springer, 2015).

Wei, F. F. et al. Visit-to-Visit Blood Pressure Variability and Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Hypertens. Dallas Tex 1549–1558 (2021). (1979) 77.

So-Ryoung, L. et al. Blood Pressure Variability and Incidence of New-Onset Atrial Fibrillation: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Hypertens. Dallas Tex (2020). (1979) 75.

Haring, B. et al. Blood pressure variability and heart failure hospitalization: results from the women’s health initiative. Am. J. Prev. Med. 63, 410–418 (2022).

Rossignol, P. et al. Increased visit-to-visit blood pressure variability is associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes in low ejection fraction heart failure patients: insights from the HEAAL study. Int. J. Cardiol. 187, (2015).

Kwon, S. et al. Visit-to-visit variability of metabolic parameters and risk of heart failure: A nationwide population-based study. Int. J. Cardiol. 293, 153–158 (2019).

Suchy-Dicey, A. M. et al. Blood pressure variability and the risk of all-cause mortality, incident myocardial infarction, and incident stroke in the cardiovascular health study. Am. J. Hypertens. 26, 1210–1217 (2013).

Harefa et al. The association between 24-h blood pressure variability and major adverse cardiac events (MACE) in hospitalized patients with acute myocardial infarction: a retrospective cohort study. Egypt. Heart J. 73, 88 (2021).

Nolan, J. et al. Prospective study of heart rate variability and mortality in chronic heart failure: results of the united Kingdom heart failure evaluation and assessment of risk trial (UK-heart). Circulation 98, (1998).

Tsuji, H. et al. Impact of reduced heart rate variability on risk for cardiac events. Framingham Heart Study Circulation. 94, 2850–2855 (1996).

Schillaci, G. et al. Relationship between Short-Term blood pressure variability and Large-Artery stiffness in human hypertension. Hypertension https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.197491 (2012).

Tedla, Y. G., Yano, Y., Carnethon, M. & Greenland, P. Association between Long-Term blood pressure variability and 10-Year progression in arterial stiffness. Hypertension 69, 118–127 (2017).

Izzo, J. L. Blood pressure variability: mechanisms, measurement, subtypes, and clinical implications. Med. Res. Arch. 10, (2022).

Mendiola, P. J. et al. Blood pressure variability compromises vascular function in middle-aged mice. eLife 14, (2025).

Su, D. F. & Miao, C. Y. Blood pressure variability and organ damage. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 28, 709–715 (2001).

Ntineri, A. et al. Prognostic value of average home blood pressure and variability: 19-year follow-up of the Didima study. J. Hypertens. 36, 69–76 (2018).

Muntner, P. et al. Visit-to-Visit variability of blood pressure and coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, and mortality: A cohort study. Ann. Intern. Med. 163, 329–338 (2015).

Gianfranco, P., Juan Eugenio, O., Carolina, L. & Grzegorz, B. Blood pressure variability: assessment, predictive value, and potential as a therapeutic target. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 17, (2015).

Veloudi, P. et al. Blood pressure variability and prediction of target organ damage in patients with uncomplicated hypertension. Am. J. Hypertens. 29, 1046–1054 (2016).

Eto, M. et al. Reduced endothelial vasomotor function and enhanced neointimal formation after vascular injury in a rat model of blood pressure lability. Hypertens. Res. Off J. Jpn Soc. Hypertens. 26, 991–998 (2003).

Nwabuo, C. C. et al. Association between Visit-to-Visit blood pressure variability in early adulthood and myocardial structure and function in later life. JAMA Cardiol. 5, 795–801 (2020).

Chao-Yu, M. & Ding-Feng, S. The importance of blood pressure variability in rat aortic and left ventricular hypertrophy produced by sinoaortic denervation. J. Hypertens. 20, (2002).

Koh, D. B. C., Gowardman, J. R., Rickard, C. M., Robertson, I. K. & Brown, A. Prospective study of peripheral arterial catheter infection and comparison with concurrently sited central venous catheters. Crit. Care Med. 36, 397–402 (2008).

Acknowledgements

All data were sourced from the MIMIC-IV database. The authors express their gratitude to the investigators for making these data available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceived and designed by P.S. and Y.Z. Data extraction, analysis, and interpretation were carried out by P.S., Y.C. and C.W. The manuscript was primarily drafted by P.S. and Y.S. Y.D. provided critical revisions and oversaw the entire research process. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statment

This research leveraged the MIMIC database. The Institutional Review Board at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center reviewed the data collection and sharing protocol, granting a waiver of informed consent and approving the initiative.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sun, Pf., Chen, Y., Zhan, YQ. et al. Association of 24-Hour blood pressure average real variability with poor prognosis in critically ill patients with coronary artery disease. Sci Rep 15, 20676 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08146-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08146-4