Abstract

The longitudinal propagation of water-quality and ecological impairments in rivers during and after wildfires remain poorly understood. In Northern California, the 2022 McKinney Fire burned 243 km2 of the Klamath National Forest, with 83% of the burned area classified as moderate to high severity. During the active wildfire, a high-intensity monsoonal rain event triggered sediment-laden flooding and runoff-initiated debris flows, causing extreme water-quality impairments and a 95 km fish kill zone along the main-stem Klamath River. This rain-on-wildfire event produced a flood wave that outpaced a sediment pulse, diminishing the dilution effect of the floodwaters. A network of high-frequency water-quality sensors recorded water-quality impairments that propagated 296 km downstream. Impairments at the nearest monitoring station, situated 71 km downstream from the fire perimeter, included dissolved oxygen sags to zero (anoxia) for 5.25 h, turbidity spikes exceeding 1000 FNU, a doubling of specific conductance from 175 to 415 µS/cm (at 25 °C), and pH anomalies of 0.5 units from 7.8 to 7.3. This novel rain-on-wildfire event triggered the first flush of fire-scar material during an active wildfire, resulting in water-quality impairments unprecedented in the historical monitoring data for the river spanning 2012 to 2022. This study provides new insights into the potential role of rain-on-wildfire events in generating extreme downstream water-quality and ecological impairments in a more fire-prone future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A more fire-prone future1 presents new challenges for managing water-quality and ecosystem services in rivers worldwide2,3,4,5. In the western United States (US), wildfire risks increasingly threaten water quality, making wildfire one of the most significant drivers of aquatic impairments6,7,8,9,10. The longitudinal propagation of water-quality impacts along river gradients is an understudied effect of wildfires10, and the mechanisms that propagate water-quality impairments in wildfire-affected rivers remain poorly understood7,11,12.

Although water-quality impacts of high-intensity wildfires, such as spikes in turbidity and dissolved oxygen sags to zero (anoxia), can lead to fish kills11,13,14,15,16,17, anoxia and sublethal physiological effects on fish and fish kills are among the least reported consequences of wildfire10,18. The scarcity of studies documenting anoxia and fish kills may reflect the scarcity of monitoring data rather than the infrequency of anoxia-related fish kills.

Post-fire longitudinal assessments of water-quality impacts are challenging because high-frequency monitoring in fire-prone areas is uncommon. Monitoring and knowledge gaps prompted recent calls for strategic and standardized monitoring to advance wildfire and water-quality science19,20. New strategies include high-frequency monitoring to investigate processes that drive interactions between fire-scar material and water quality, which is a key knowledge gap for predicting water-quality and ecological impairments during and following wildfires10.

The longitudinal propagation of wildfire-related water-quality impairments is an emerging area of research7,12,18. A recent study by Ball et al.7 used an exponential decay model and an impact threshold, defined as a decline in dissolved oxygen of > 0.5 mg/L, to estimate the total stream + river length impacted by wildfires across the western US. Between 1984 and 2014, wildfires directly affected approximately 6% of the stream + river lengths in fire-prone areas. When Ball et al.7 incorporated the longitudinal propagation of water-quality impacts, the estimate nearly doubled to ~ 11%, indicating that longitudinal propagation of fire-scar material elevates the risk of water-quality and ecological impairments in fire-prone ecosystems.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first published work documenting a rain-on-wildfire event and the longitudinal propagation of water-quality and ecological impairments. We investigate a high-intensity monsoonal rainfall event that triggered sediment-laden flooding, runoff-initiated debris flows, and the first flush of fire-scar material during an active wildfire. Subsequently, we discuss potential mechanisms for dissolved oxygen sags to zero (anoxia) and the complex interactions between the propagation of a flood wave and sediment pulse, composed of fire-scar material, which intensified downstream water-quality impairments and produced a 95 km fish kill zone.

Our specific study objectives were to examine water-quality responses to the 2022 McKinney rain-on-wildfire event and to explore patterns in the longitudinal propagation of water-quality impairments using high-frequency monitoring of turbidity, conductivity, pH, dissolved oxygen, and water temperature. This study presents a new understanding of rain-on-wildfire events and their role in producing extreme water-quality and ecological impairments in downstream receiving waters.

Study area

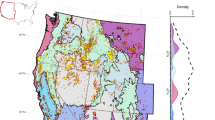

The Klamath River drains more than 40,600 km2 of northern California and southern Oregon (Fig. 1). The basin is steep and rugged, the climate is Mediterranean, and precipitation mainly occurs from October to April21. Annual precipitation varies from 3300 mm in the west to 250 mm in the east. Seasonal snowpack typically forms above 1200 m. Most annual precipitation is produced by Pacific frontal storms during the fall and winter months. In late summer and early fall, monsoonal moisture occasionally brings short-duration thunderstorms with high-intensity rainfall.

2022 McKinney rain-on-wildfire study area on the main-stem Klamath River, California. The map shows burned areas from historical wildfires between 2013 to 2022, burned areas for the 2022 McKinney Fire and 2022 Yeti Fire, major tributaries, four dams removed in 2023 and 2024, and three monitoring stations. River distances, measured upstream from the river mouth, are 282 km to the confluence of Humbug Creek, 272 km to the confluence of Vesa Creek, 211 km to the Seiad station (USGS station number 11520500), 96 km to the Orleans station (USGS station number 11523000), and 13 km to the Klamath station (USGS station number 11530500). Photos taken the week after the rain-on-wildfire event show (a) a post-fire debris flow (PFDF) scar in the headwaters of Vesa Creek58, (b) a debris fan at the confluence of Vesa Creek with the main-stem Klamath River58, (c) active fire and fish kill (Karuk Tribe), and (d) and sample of fire-scar material in transport at the Klamath station (Public Domain). Figure created using ArcGIS Pro (v. 10.6; Esri, Redlands, CA, USA).

Historically, the Klamath River was the third-largest salmon-producing river on the West Coast of the US and supported a culturally and economically significant salmon fishery22,23. Cumulative effects from multiple stressors have caused severe declines in native fish populations24. Estimated declines since the early 1900s range from 52 to 95% for endangered coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch), over 90% for fall-run Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), 98% for spring-run Chinook salmon, 67% for steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), and 98% for Pacific lamprey (Entosphenus tridentatus)22. Historical declines in salmon populations were attributed to fish disease25,26, poor water quality27, and insufficient scouring flows28,29,30.

Dams, reservoir operations, decades of fire suppression, and recent increases in the frequency of high-intensity wildfires played important roles in the decline of native fish populations in the Klamath River basin. In 2002, when reservoir flow releases were reduced during a dry year with a high prevalence of fish disease31,32, more than 33,000 adult salmon, steelhead trout, and other fish species died of disease (Ichthyophthirius multifiliis and Flavobacterium columnare). The fish kill in 2002 served as a catalyst for basin-scale water-quality monitoring. Following the 2002 fish kill, seasonal sondes were installed at existing US Geological Survey (USGS) streamflow stations. In 2018, in preparation for the removal of four hydroelectric dams (Fig. 1), turbidity sensors and suspended-sediment monitoring were added. The dam removals are expected to improve water quality and reduce fish disease33,34,35. The first dam was removed in October 2023, and the remaining three were removed during the summer of 2024.

Historic fire suppression36, unprecedented above-ground live (AGL) tree biomass37, and persistent drought38 increased the availability of dry fuels and the risk of high-severity wildfires throughout the Klamath River basin. Current AGL tree biomass estimates are unprecedented (250 Mg/ha) and more than double the long-term median (104–128 Mg/ha) for the past 3,000 years37. From 2013 to 2022, approximately 37% (7300 km2) of the lower Klamath River basin below Iron Gate Dam was burned by wildfires (Fig. 1). These historic wildfires include large, high-severity fires, such as the 2022 McKinney Fire, which burned 243 km2, as well as smaller, lower-severity fires, like the 2022 Yeti Fire, which burned 32 km243.

During the summer of 2022, the Yeti and McKinney wildfires burned along an 84-km reach of the main-stem Klamath River (Fig. 1). The downstream Yeti Fire started on July 28, 2022, and the upstream McKinney Fire began on July 29, 2022. On August 2, 2022, a high-intensity monsoonal rainfall event occurred over the McKinney Fire, hereafter referred to as the McKinney rain-on-wildfire event.

Methods

In this study, we used geospatial datasets to assess the timing and extent of burned areas, wildfire severity, rainfall intensity, rainfall volumes, and sediment delivery from post-fire debris flows (PFDFs). Subsequently, we utilized streamflow and water-quality observations collected at three monitoring stations (Fig. 1 and Table 1) to examine the responses of streamflow and water quality and explore patterns in the longitudinal propagation of a flood wave and sediment pulse that caused extreme water-quality and ecological impairments in the downstream receiving waters of the main-stem Klamath River.

Rain-on-Wildfire analysis

We used analysis-ready data (ARD) to assess the timing and extent of burned areas, wildfire severity, rainfall rates and accumulations, and sediment delivery by PFDFs during the McKinney rain-on-wildfire event. ARD is a recent concept intended to provide standardized geospatial products for analysis. We estimated the timing and extent of burned areas using the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS MCD64A1) Burned Area product suite39. We created burn severity maps using the Normalized Burn Ratio (NBR), a remote sensing index that distinguishes healthy vegetation from burned vegetation40. We estimated rainfall rates and accumulations using Next Generation Weather Radar (NEXRAD) Q3 RADAR-only gridded maps41, and we used PFDF volumetric predictions42 to estimate sediment delivery from burned areas.

The MODIS-MCD64A1 product provided daily estimates of burned areas39. The burned area data are derived from 500 m MODIS imagery and 1 km MODIS active fire observations. This burned area product consists of polygons, each attributed with an ordinal burn day value (1–366). We downloaded the 2022 burned area polygons and merged all polygons with burn dates on or before August 1, 2022. These merged polygons represent the total extent of burned areas before August 2, 2022. The burned area maps have a spatial resolution of 500 m.

We used NBR data, with pixel values representing the difference between pre-fire and post-fire values, hereafter referred to as dNBR, to characterize fire severity for the 2022 Yeti Fire and McKinney Fire extents43. We classified the dNBR grids using standardized burn severity thresholds to distinguish between unburned (dNBR between −0.100 and 0.99), low severity (dNBR between 0.100 and 0.269), moderate severity (dNBR between 0.270 and 0.439), and high severity (dNBR between 0.660 and 1.30) classes40. The dNBR grids for the Yeti Fire and McKinney Fire have a spatial resolution of 20 m.

Because there were no nearby ground-based stations with measured rainfall for the rain-on-wildfire event, we computed rainfall rates and accumulations using NEXRAD gridded reflectivity maps. NEXRAD reflectivity-derived rainfall estimates are recorded and updated every 56 min during precipitation events. When confounding factors are well-constrained, NEXRAD estimates of rainfall rates and accumulations are commonly within 20% of nearby ground-based measurements but can differ by a factor of 244.

We summarized rainfall rates and storm accumulations using NEXRAD Q3 RADAR-only gridded maps with 5–6 min estimates of rainfall rates and 1 h accumulations41. The 1 h accumulation grids represent the total accumulated rainfall since the last one-hour break in precipitation. We used the NOAA Weather and Climate Toolkit (WCT) App45 to reproject the precipitation grids from polar to planar coordinates. The reprojected rainfall grids have a spatial resolution of 120.5 m.

We used ArcPro (v.10.6) to clip and analyze the NEXRAD rainfall data and NOAA Atlas 14 to estimate the rainfall frequency46. The rainfall rate and 1-h accumulation grids were clipped using the burn-scar perimeters for the 2022 McKinney and Yeti fires. We used the gridded maps of 5–6 min rainfall rates to determine storm duration and rainfall intensities, and we summed the gridded maps of 1 h rainfall accumulations to compute 3 h rainfall accumulations for each pixel and estimate 3 h storm totals. We determined rainfall recurrence intervals and exceedance probabilities, using NOAA Atlas 14 searchable lookup tables.

We estimated sediment delivery from burned areas using PFDF predictions computed using standardized empirical models52. The volumetric predictions were derived from multiple linear regression models that estimate the likelihood and volume of PFDFs in recently burned areas47. These models use parameters related to the watershed shape, burn severity, soil properties, and rainfall to predict likelihood and volumetric estimates for PFDFs in response to design storms.

Streamflow and water-quality monitoring

To explore patterns in the longitudinal propagation of water-quality and ecological impairments along the main-stem Klamath River, we used high-frequency monitoring data collected at three stations jointly operated by the USGS, the Karuk Tribe, and the Yurok Tribe (Fig. 1 and Table 1). We investigated the propagation of a flood wave using 15 min streamflow observations, and we examined the propagation of a sediment pulse composed of fire-scar material using 15 min water-quality observations. Streamflow and water-quality data were collected, archived, analyzed, and approved in accordance with standard USGS methods48,49. We used turbidity as a surrogate measurement for sediment50.

Water-quality data were collected by the Karuk Tribe and Yurok Tribe using multiparameter sondes (EXO2, YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, Ohio, USA). The sondes were equipped with a central wiper, a combined water temperature (°C) and specific conductance (μS/cm at 25 °C) sensor, an optical dissolved oxygen (mg/L) sensor, a pH sensor, and an optical turbidity sensor (FNU). The turbidity sensors have a maximum read range of 2,000 FNU; however, accuracy declines above 1,000 FNU51. The sondes were programmed to collect a 40 s burst of data from each sensor, which was then averaged and recorded for each 15 min timestamp. Biological activity and growth, referred to as biofouling, can interfere with sensor readings. The sondes were programmed to wipe the sensors before each measurement, and the sensors were cleaned monthly to minimize biofouling.

All streamflow and water-quality observations used in this study are publicly available (Table 1). The 15 min streamflow data were collected by the USGS and published in the National Water Information System52. The 15-min water-quality data at the Seiad (USGS station number 11520500) and Orleans (USGS station number 11523000) stations were collected and published by the Karuk Tribe53. The 15 min water-quality data at the Klamath station (USGS station number 11530500) were collected and published by the Yurok Tribe54. Turbidity data at all three monitoring stations, collected by the Karuk and Yurok Tribes, were furnished to the USGS. The furnished turbidity data were reviewed and approved by the USGS and published in the National Water Information System52.

Propagation of a flood wave and sediment pulse

Streamflow and turbidity observations collected at the Seiad, Orleans, and Klamath monitoring stations (Fig. 1 and Table 1) were used to interpret the longitudinal propagation of a flood wave and sediment pulse composed of fire-scar material. In this context, “flood wave” refers to the rapid rise and fall of streamflow produced by surface runoff55,56, and the pulse of fire-scar material composed of ash, charcoal, sediment, and fire retardant is termed a “sediment pulse”. We investigated flood wave propagation using time series plots of streamflow (hydrographs) and sediment pulse propagation using time series plots of turbidity (turbidigraphs).

We calculated travel distances, longitudinal travel times, lag times, flood wave celerities (km/h), and sediment pulse velocities (km/h). Travel distances were computed from the McKinney Fire perimeter at the Humbug Creek confluence downstream to the Seiad, Orleans, and Klamath monitoring stations using published river distances57. Longitudinal travel times from the fire perimeter to each monitoring station for both the flood wave and sediment pulse were computed using the time differences between the end of the rain-on-wildfire event and the arrival of the flood wave and sediment pulse. Arrival times for the flood wave were determined using the date and time of streamflow peaks, while arrival times for the sediment pulse were determined using the date and time of turbidity peaks. We identified these dates and times using the maximum streamflow and turbidity values. Lag times between the arrival of the flood wave and sediment pulse were computed as the time difference between the arrival of the streamflow and turbidity peaks. Flood wave celerities and sediment pulse velocities were computed as river distance (km) divided by travel time (h), with travel times estimated as the difference between the end of the rainfall event and the arrival of the streamflow and turbidity peaks respectively.

Water-quality impairments

We evaluated water-quality responses at the Seiad, Orleans, and Klamath stations using observations from July 28, 2022, to August 14, 2022. For each station, we assessed the streamflow response to monsoonal rainfall and analyzed the timing, magnitude, and duration of water-quality responses to the first flush of fire-scar material. Subsequently, we examined the timing, magnitude, and duration of the flood wave and sediment pulse, as well as the response of conductivity, dissolved oxygen, pH, and water temperature, to explore complex interactions between the flood wave, sediment pulse, and water-quality parameters.

To identify anomalous excursions in water quality indicative of wildfire effects, we focused on the Seiad station (Fig. 1) and compared the 2022 water-quality observations from July to September with historical data spanning 2012 to 2021. To assess the water-quality anomalies, we compared the timing of the maximum instantaneous (15 min) values in turbidity and conductivity to the minimum instantaneous (15 min) values in dissolved oxygen, pH, and water temperature. The historical turbidity data covers four years (2018–2021), while streamflow and other water-quality data span ten years (2012–2021).

Results

Rain-on-wildfire summary

The Yeti Fire started on July 28, 2022, burned 32 km2, and was fully contained on September 1, 2022. The McKinney Fire began on July 29, 2022, burned 243 km2, and was fully contained on October 1, 2022. The Yeti Fire directly impacted 16 km of the main-stem river (river kilometers 198 to 214), while the McKinney Fire directly impacted 25 km (river kilometers 247 to 272). According to the MODIS-MCD64A1 Burned Area product analysis, 1% of the McKinney Fire burned from July 29–30, 2022, 89% burned from July 31 to August 2, 2022, and 10% burned on or after August 3, 2022 (Fig. 2a). The severity maps (Fig. 2b;43) indicate that the areas burned by the Yeti Fire were primarily unburned (22%) or low burn (40%) severity, while the areas burned by the McKinney Fire exhibited a predominance of moderate (46%) to high (37%) burn severity.

Geospatial datasets used to assess the downstream water-quality impacts of the 2022 McKinney rain-on-wildfire event on the main-stem Klamath River, California. The rain-on-wildfire event triggered sediment-laden flooding and post-fire debris flows (PFDFs) in the Vesa and Humbug watersheds, delivering the first flush of fire-scar material to the downstream receiving waters of the Klamath River. Panel (a) shows burned areas for the 2022 McKinney Fire and 2022 Yeti Fire on August 2, 2024, the location of the Seiad monitoring station, and river distances upstream from the Pacific Ocean. Thin blue lines represent tributary channels impacted by the Yeti Fire and McKinney Fire. Red outlines represent wildfire boundaries. Black outlines represent the Vesa and Humbug watersheds that produced sediment-laden flooding and PFDFs. Panel (b) shows burn severity maps43. Panel (c) shows estimates of the minimum predicted PFDF volumes computed using a design storm with a 15 min rainfall intensity of 40 mm/h52. Panel (d) shows maximum rainfall rates on August 2, 2024, at 20:23 PDT computed using NEXRAD 5-6 min rainfall rate estimates measured by the KMAX weather station (NCDC, 2023a). Panel (e) shows 3-h rainfall accumulations on August 2, 2024, between 17:30 and 20:30 PDT, computed from hourly accumulation estimates measured by the KMAX Station (NCDC, 2023a). The highest 3-h rainfall accumulations occurred in Humbug Creek, while the highest rainfall rates, burn severity, and erosion by PFDFs occurred in Vesa Creek. Figure created using ArcGIS Pro (v. 10.6; Esri, Redlands, CA, USA).

On August 2, 2022, an unsettled weather pattern initiated monsoonal flow from the south, directing warm, moist air into northern California. At approximately 17:30 PDT, monsoonal moisture produced a convective thunderstorm over the active perimeter of the McKinney Fire. The storm generated localized cells of intense rainfall lasting ~ 3 h from 17:30 to 20:30 PDT. Initially, the storm produced intense rainfall over the Humbug Creek watershed, triggering sediment-laden flooding. As the storm migrated into the steeper Vesa Creek watershed, sustained rainfall intensities triggered rill and gully erosion and PFDFs58.

In the Vesa and Humbug watersheds, estimated rainfall rates exceeded 200 mm/h (Fig. 2d), with 3 h rainfall accumulations surpassing 100 mm (Fig. 2e). In isolated cells, rainfall rates exceeded 150 mm/h for more than 30 min and 200 mm/h for over 5 min. Such extreme rainfall is uncommon during the summer low-flow season in the Klamath River basin. The recurrence interval for a rainfall event with a peak 15 min intensity of 100 mm/h in the Vesa and Humbug watersheds is over 1000 years, with an annual exceedance probability of less than 0.001%46.

During the rain-on-wildfire event, NEXRAD gridded precipitation maps show no rainfall over the Yeti Fire scar (Fig. 2d,e). The rainfall analysis indicated that localized high-intensity precipitation was confined to the the Vesa and Humbug watersheds within the active perimeter of the McKinney Fire. Although the Yeti Fire scar may have contributed runoff and sediment during other events, we assumed that any runoff and sediment mobilized and delivered from the low-severity Yeti Fire scar was minor during the rain-on-wildfire event.

Vesa Creek and Humbug Creek (Fig. 2) were the primary sources of sediment-laden flooding and runoff-initiated debris flows that delivered fire-scar material to the main-stem Klamath River. These two headwater basins are steep mountain watersheds with highly erodible hillslopes underlain by deeply weathered soils and regolith58. When monsoonal moisture moved from the headwaters of Humbug Creek into Vesa Creek (Fig. 2), orographic enhancement59 produced extreme rainfall intensities.

Post-event field reconnaissance indicated extensive rill and gully erosion of burned hillslopes in the Vesa and Humbug watersheds58. Intense rainfall exceeded the infiltration capacity of fire-affected soils and regolith, producing runoff that triggered rill and gully erosion, and creating sediment slurries that coalesced and transitioned into debris flows in areas underlain by deeply weathered regolith and colluvium. Runoff-initiated debris flows scoured channel reaches, uprooted riparian vegetation, and deposited debris fans in lower gradient reaches of Vesa Creek and Humbug Creek, where the tributary channels flow into the main-stem river.

NEXRAD estimates of rainfall rates over the Vesa and Humbug watersheds (Fig. 2d) were well above the maximum design storm thresholds computed for the McKinney PFDF hazard models. The minimum PFDF volumetric predictions for the McKinney Fire, computed using a maximum-intensity design storm with a 15 min rainfall rate of 40 mm/h (Fig. 2c;52, were 24,000 m3 for Vesa Creek and 57,000 m3 for Humbug Creek. The maximum PFDF volumetric predictions, computed using the same design storm, were 1,554,000 m3 for Vesa Creek and 3,676,000 m3 for Humbug Creek52. Summing these PFDF volumetric predictions suggests the potential sediment delivery to the main-stem Klamath River by PFDFs during the rain-on-wildfire event was likely more than 81,000 m3 and may have exceeded 5,230,000 m3.

Propagation of a flood wave and sediment pulse

Studies that investigate the complex interactions between flood waves and sediment pulses during and following wildfires are uncommon because high-frequency monitoring in fire-prone areas is rare. To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a detailed analysis of the longitudinal propagation of the flood wave, sediment pulse, and water-quality impairments.

The rain-on-wildfire event created a flood wave and sediment pulse that propagated 71 km (Table 1) downstream from the confluence of Humbug Creek with the main stem (river kilometer 282), past the confluence with Vesa Creek (river kilometer 271), to the Seiad station (river kilometer 211). At 01:45 PDT on August 3, 2022, streamflow at the Seiad station began to rise, and at 05:45 PDT, a streamflow peak arrived approximately 9.25 h after the rainfall event ended (Table 2). Streamflow doubled from 29 to 58 m3/s over 4 h when the flood wave arrived (Fig. 3). The first turbidity peak occurred at 14:45 PDT (~ 9 h after the streamflow peak), a second peak arrived at 21:45 PDT (~ 16 h after the streamflow peak), and a third peak arrived on August 4 at 05:00 PDT (~ 23.25 h after the streamflow peak).

Continuous 15 min streamflow and water-quality observations showing the longitudinal propagation of a flood wave, sediment pulse, and associated water-quality impairments captured at three downstream monitoring stations52,53,54 following the 2022 McKinney rain-on-wildfire event along the main-stem Klamath River, California. Time-series graphs show peaks in streamflow that preceded the arrival of turbidity pulses. Spikes in turbidity and specific conductance (SC), and sags in dissolved oxygen (O2) and pH were in sync with the arrival of the turbidity pulse at each station. The duration of the rain-on-wildfire event is shown in each panel by the shaded red area. Water-quality impairments were most pronounced upstream, closest to the sediment pulse source areas, and generally decreased with increasing distance downstream. Monitoring station locations are reported in parentheses as kilometers (km) downstream from Humbug Creek, a primary sediment source watershed. Station descriptions are shown in (Table 1), and station locations are shown in (Fig. 1).

As the flood wave and sediment pulse propagated downstream past the Yeti Fire perimeter (river kilometer 214 to 198) to the Orleans station (river kilometer 96) and Klamath station (river kilometer 13), the turbidity peaks coalesced into a single peak, and the magnitude of the streamflow peaks and water-quality impairments diminished (Fig. 3). At the Orleans station, the streamflow peak arrived 27 h after the rain event ended, and a single turbidity peak arrived 57.5 h after the streamflow peak (Table 2). Further downstream at the Klamath station, the streamflow peak arrived 41 h after the rain event ended, and a single turbidity peak arrived 92.5 h after the streamflow peak (Table 2).

The rain-on-wildfire event occurred during the low-flow season, with minimal additions of streamflow and sediment between the monitoring stations, allowing us to compute flood wave celerities and sediment pulse velocities. Herein, flood wave celerity is defined as the speed of a flood wavefront as it propagates through a river channel. We assumed that floodwaters and sediment initially exited the Vesa and Humbug watersheds immediately after the monsoonal rainfall event on August 2 at 20:30 PDT. If floodwaters and fire-scar material entered the main-stem Klamath River earlier, the computed travel times would be underestimated, leading to an overestimation of the associated flood wave celerity and sediment pulse velocity.

The flood wave and sediment pulse became decoupled as they propagated downstream, and the estimated lag times progressively increased with distance (Table 2). Consequently, the flood wave traveled 2 to 3.3 times faster and outpaced the sediment pulse. Between the Humbug Creek confluence and the Seiad station, the flood wave’s celerity was 6.6 km/h, while the velocity of the first sediment pulse to arrive was 3.3 km/h. From the Seiad station to the Orleans station, the flood wave celerity declined to 4.2 km/h, while the velocity of the coalesced sediment pulse decreased to 1.4 km/h. Between the Orleans station and the Klamath station, the flood wave celerity further declined to 2.0 km/h, and the sediment pulse velocity dropped to 0.6 km/h.

Water-quality impairments and fish kill

During the rain-on-wildfire event, we observed excursions in water quality at the Seiad, Orleans, and Klamath stations, including spikes in turbidity and conductivity, as well as sags in dissolved oxygen and pH (Fig. 3). Herein, “sag” is defined as a rapid decline in a water-quality parameter followed by recovery plotted over time. At all three monitoring stations, turbidity and conductivity spiked as dissolved oxygen and pH declined (Fig. 3). In contrast, the response of water temperature was out of sync with other water-quality responses at all three monitoring stations, indicating that air temperature or other factors influenced changes in water temperature.

At the Seiad station, located within the 95 km fish kill zone (Fig. 1), we observed three distinct spikes in turbidity and conductivity, as well as three separate sags in dissolved oxygen and pH (Fig. 3), which were unprecedented in historical observations (Fig. 4). Turbidity increased and exceeded 1,000 FNU for over 5 h, and the actual turbidity values may have been higher than the recorded values because the accuracy of the turbidity sensors used in this study declined above 1,000 FNU51. Specific conductance increased from 175 to 415 µS/cm (at 25 °C). Anoxia occurred when dissolved oxygen dropped to zero for a total of 5.25 h and was likely the primary cause of the fish kill. Dissolved oxygen remained below 5 mg/L, and pH remained below 7.5 for over 16 h. Daytime water temperatures briefly increased by 0.5 °C on August 3, 2022, then cooled by 1.0 °C from August 4 through August 7, 2022.

Continuous 15 min streamflow and water-quality observations showing unprecedented and acute water-quality impairments captured at the Seiad station, within a 95 km fish kill zone and located 211 km upstream from the Pacific Ocean and 71 km downstream from the Humbug Creek confluence along the main-stem Klamath River, California. Time-series graphs show streamflow, turbidity, specific conductance (SC), dissolved oxygen (O2), pH, and water temperature observations from July to September and show the 2022 data collected before, during, and after the McKinney rain-on-wildfire event in the context of historical data spanning 2012 to 2021, with turbidity data spanning 2018 to 2021. The Seiad station description is in (Table 1), the Seiad station location is shown in (Figs. 1, 2), and the fish kill zone is shown in (Fig. 1).

As the sediment pulse propagated further downstream, the magnitude of water-quality impairments attenuated (Fig. 3). At the Orleans station, the arrival of the sediment pulse coincided with a spike in turbidity that exceeded 1,000 FNU for more than 4 h, while conductivity increased from 168 to 278 µS/cm (at 25 °C), dissolved oxygen decreased by 0.7 mg/L from 7.4 to 6.7 mg/L, and pH decreased by 0.4 units from 8.1 to 7.7. At the Klamath station, the arrival of the sediment pulse coincided with elevated turbidity levels that remained above 550 FNU for over 8 h, conductivity increase from 168 to 278 (µS/cm at 25 °C), dissolved oxygen declined by 1.1 mg/L from 7.4 to 6.3 mg/L, and pH decreased by 0.3 units from 8.1 to 7.8.

A comparison of the 2022 water-quality observations, collected from July through September at the Seiad station, with historical observations from 2012 to 2021 shows excursions indicative of wildfire effects (Fig. 4). Thresholds for interpreting excursions were turbidity above 80 FNU, conductivity above 250 µS/cm (at 25 °C), pH below 7.5, and dissolved oxygen below 6 mg/L. The historical data showed no large excursions. In stark contrast to the historical data, the rain-on-wildfire event created unprecedented spikes in turbidity that exceeded 1,000 FNU and conductivity that exceeded 400 µS/cm (at 25 °C), pH sags to 7.3, and periods of hypoxia (dissolved oxygen < 2 mg/L) and anoxia (dissolved oxygen = 0 mg/L; Fig. 4).

Discussion

In rivers, streamflow and turbidity peaks rarely occur simultaneously56, and counterclockwise hysteresis following wildfires is common60. Counterclockwise hysteresis occurs when turbidity is lower on the rising limb than on the falling limb of a hydrograph and may reflect distal sediment sources with longer travel times or slower mobilization61,62. Conversely, clockwise hysteresis occurs when turbidity is higher on the rising limb than on the falling limb of a hydrograph, which may indicate sediment contributions from proximal sources with shorter travel times or rapid mobilization. During the rain-on-wildfire event, lag times between the arrival of the flood wave and the sediment pulse progressively increased as both propagated downstream, causing strong counterclockwise hysteresis.

Unless additional sediment is entrained from a tributary or main-stem source, hysteresis will progressively increase with downstream distances55,56, due to differences in flood wave celerity and sediment pulse velocity63,64. Celerity and velocity often differ because they are influenced by distinct processes65. Generally, celerity is defined as the rate at which a disturbance in flow propagates through a flow domain, whereas velocity is the rate at which a distinct mass changes its position, characterized by both speed and direction.

The longitudinal propagation of a flood wave through a river channel is controlled by wave celerity, whereas sediment pulse velocities are controlled by the mean streamflow velocity66,67. During the rain-on-wildfire event, flood wave celerity controlled the hydrograph and the arrival time of the streamflow peak, while mean streamflow velocity controlled the transport of suspendable-sized fire-scar material and the arrival time of the turbidity peak. Generally, flood wave celerities are considerably faster than sediment pulse velocities67, and the progressive lag of a sediment pulse behind a flood wave is most apparent when a single storm event produces a fine-sediment pulse that travels long distances downstream55,56. The rain-on-wildfire event illustrated these principles. When the flood wave outpaced the sediment pulse, traveling downstream 2 to 3.3 times faster, the flood wave became decoupled from the sediment pulse, the dilution effect of the floodwaters decreased, and downstream water-quality impairments intensified.

During the rain-on-wildfire event, water-quality impairments varied longitudinally between monitoring stations. This variability may be linked to differences in river processes, land use, and geology, or to additions of streamflow, reactive carbon, or reactive metals. While ash inputs from wildfire runoff can increase pH due to the alkaline nature of ash material6,11, decreases in pH (~ 0.75 units) can be linked to biological or chemical processes during periods of very high turbidity9,18. Dissolved oxygen sags to zero (anoxia) observed at the Seiad station may suggest rapid microbial respiration, which could reduce pH due to the production of carbon dioxide68 or may indicate rapid oxidation of reduced metals releasing hydrogen ions into solution, leading to a decrease in pH69. The spikes in conductivity (a measure of dissolved ions) may be attributed to the influx of ash and mineralized soils from areas with high burn severity9.

This study used streamflow and water-quality observations collected at existing stations along the main-stem Klamath River to investigate water-quality impairments. The number and location of the pre-existing stations effectively captured longitudinal variations in streamflow and water quality with sufficient accuracy and detail to support analyses of the longitudinal propagation of water-quality impairments. However, the magnitude and possibly the duration of these impairments were likely greater within the McKinney Fire perimeter and immediately downstream of the Humbug Creek and Vesa Creek confluences.

The magnitude of water-quality responses diminished as the flood wave and sediment pulse propagated from the Seiad station downstream to the Orleans and Klamath stations. Clearwater additions from tributaries serve as a primary mechanism for mitigating extreme water-quality impacts in wildfire-affected rivers. On August 1, 2022, the day before the rain-on-wildfire event, mean daily streamflow was 29 m3/s at the Seiad station, 47 m3/s at the Orleans station, and 84 m3/s at the Klamath station. Muted water-quality responses at the Orleans and Klamath stations may be attributed to dilution by the addition of tributary streamflow or higher decomposition rates closer to sources of the fire-scar material, resulting in less reactive material being transported downstream.

In rivers, the consumption of dissolved oxygen occurs through two mechanisms: biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and chemical oxygen demand (COD). The impacts of BOD and COD on dissolved oxygen during and following large wildfires is an emerging area of research9,10,18. In this study, the data required to differentiate between rates of BOD and COD was unavailable. Either BOD, COD, or a combination of both may have contributed to the observed responses in dissolved oxygen at the monitoring stations.

During and following large wildfires, reaeration is a primary mechanism for buffering declines in dissolved oxygen caused by BOD and COD70. Variations in turbulence and reaeration along the main-stem Klamath River may have influenced dissolved oxygen responses. The factors influencing turbulence and reaeration along the main-stem of the Klamath River include channel gradient, water depth, stream flow velocity, wind speed, wave action, and roughness27.

Higher-gradient reaches have more mixing energy available to facilitate faster reaeration, and turbulent river reaches are better able to buffer declines in dissolved oxygen during and following wildfires70. The Seiad and Orleans stations are in high reaeration reaches characterized by steeper channel gradients, larger bed material, higher relief riffles, and greater turbulence. In contrast, the Klamath station is in a low reaeration reach, characterized by gentler channel gradients, smaller bed material, longer pools, lower relief riffles, and less turbulence27,34. The Seiad station experienced the longest duration of elevated turbidity and dissolved oxygen sags to zero (anoxia). The magnitude and duration of dissolved oxygen sags at the Orleans and Klamath stations were similar. Although turbidity was substantially lower in the Klamath reach, the Orleans reach reaerated more quickly.

Following the rain-on-wildfire event, the recovery of diel variations in dissolved oxygen was delayed (Fig. 3). Generally, diel variation in dissolved oxygen increases with increasing gross primary production (GPP) and ecosystem respiration. GPP can be influenced by reaeration; in reaches with relatively stable reaeration, decreases in primary production can cause lower diel variations in dissolved oxygen. During and following the rain-on-wildfire event, dissolved oxygen responses suggest that GPP rates were suppressed. Suppressed GPP may have been caused by external factors, such as reduced light or declines in aquatic plant and algal biomass71.

The propagation of sediment pulses can scour and bury benthic organisms (epilithic algae, filamentous green algae, and rooted aquatic macrophytes) that contribute to GPP72,73. Moreover, extreme turbidity events can severely limit the light necessary for primary production in all but the shallowest locations74,75. Scour and burial of primary producers, along with extreme turbidity during the rain-on-wildfire event, likely contributed to GPP suppression.

At the Seiad station, turbidity declined following the initial spike and remained elevated through mid-September, while the diel variation in dissolved oxygen recovered but remained muted through mid-September (Fig. 4). Following the rain-on-wildfire event, dilution flows to mitigate fish disease during the fall salmon run were released from upstream reservoirs formerly impounded by dams recently removed in 2023 and 2024 (Fig. 1). At the Seiad Station, the dilution flows created a small turbidity spike and low amplitude sags in dissolved oxygen (Fig. 4) illustrating long-lasting impacts of the rain-on-wildfire event on GPP along 71 km of the main-stem Klamath River.

Water-quality impairments are stressful and can be lethal when fish are exposed to high suspended-sediment concentrations76 or dissolved oxygen concentrations below 2 mg/L77. The 2022 McKinney rain-on-wildfire event produced a flood wave, sediment pulse, and water-quality impairments that propagated 269 km downstream from the confluence of Humbug Creek to the Klamath station, producing a 95 km fish kill zone. Although there was no official census of the fish kill caused by the rain-on-wildfire event, field observations by the Karuk Tribe Fisheries Department indicated that approximately 10,000 fish died. The fish kill primarily included non-anadromous resident fish species, but out-migrating anadromous juveniles and incoming anadromous fall spawners may have also been affected.

The rain-on-wildfire event produced the first flush of fire-scar material during the summer low-flow season on the hottest day of the year, when base flows and clear water contributions from tributaries were at a minimum. Low flow conditions intensified downstream water-quality and ecological impairments, which were further exacerbated by hysteresis, as the flood wave outpaced the sediment pulse. During the summer months, salmon typically seek cold-water refugia. If this event had occurred during the fall spawning run, it could have had catastrophic effects on threatened salmon populations. Given that wildfires in the western US primarily occur during the low flow season, rain-on-wildfire events represent a unique class of first-flush events with a high likelihood of causing extreme water-quality and ecological impairments in downstream receiving waters.

To the best of our knowledge, only three published studies exist worldwide that document anoxia during or following large wildfires. These studies include the 2011 Las Conchas Fire18, the 2022 Hermit’s Peak-Calf Canyon Fire12, and this study of the 2022 McKinney rain-on-wildfire event. There are commonalities among these studies. All three fires occurred in forested basins, and high-intensity monsoonal rainfall triggered a first flush event, leading to severe water-quality impairments and anoxia in downstream river reaches. In each case, anoxia was likely driven by increases in BOD and COD stimulated by the influx of organic-rich, chemically reduced fire-scar material. The scarcity of studies documenting anoxia during or following wildfires may reflect the scarcity of high-frequency monitoring capable of capturing transient occurrences of anoxia in wildfire-affected rivers rather than the infrequency of anoxia events.

Predictions of a more fire-prone future across the western US1, accompanied by increases in probable maximum precipitation78, suggest that fire-related sediment delivery79 and downstream water-quality impairments3 will likely increase. Despite the Klamath River basin being in California’s wettest region, it is experiencing significant increases in the frequency, severity, and size of wildfires80.

In a more fire-prone future, low-intensity fires are less likely to cause downstream water-quality and ecological impairments81,82. In the absence of intense rainfall, naturally occurring and controlled small and low-intensity fires, such as the 2022 Yeti Fire, may help reduce the availability of dry fuels in the Klamath River basin without noticeably affecting downstream water quality and ecology.

Rain-on-wildfire events are rare but may become more frequent with increasingly extreme future climates. The 2022 McKinney rain-on-wildfire event was extraordinary, resulting in unprecedented downstream water-quality impairments. Fire-prone areas that experience seasonal drought and late summer monsoonal rainfall are particularly vulnerable to rain-on-wildfire events. Future climatic warming and the strengthening of warm-season monsoonal storms83 under drier future climates84 could amplify the frequency and severity of rain-on-wildfire events across the western US.

Conclusions

The longitudinal propagation of water-quality and ecological responses to wildfires remains poorly understood due to the scarcity of high-frequency monitoring in fire-prone areas. The scarcity of studies documenting dissolved oxygen sags to zero (anoxia) may reflect a lack of monitoring data rather than the infrequency of wildfire-driven anoxia and related fish kills. Rain-on-wildfire events represent a unique class of first-flush events with a greater likelihood of causing extreme water-quality and ecological impairments in downstream receiving waters. This study highlights the elusive and transient nature of extreme water-quality and ecological impairments during active wildfires, providing novel insights into the potential role of rain-on-wildfire events in an increasingly fire-prone future. The findings emphasize the importance of high-frequency monitoring in fire-prone areas to assess transient water-quality impairments during active wildfires and to inform forest and river management strategies aimed at enhancing ecosystem resilience to wildfires.

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study are publicly available in databases managed by the National Climate Data Center (NCDC41; https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/nexradinv/), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Giglio39; https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MCD64A1.061), U.S. Geological Survey (USGS52; https://doi.org/10.5066/F7P55KJN), Karuk Tribe Water Quality Department (Karuk Tribe53, https://waterquality.karuk.us/), and Yurok Tribe Environmental Department (Yurok Tribe54, https://www.yuroktribe.org/environmental-department/). Please contact Karuk and Yurok tribal corresponding authors directly for data inquiries.

References

Fu, R., Hoell, A., Mankin, J., Sheffield, A. & Simpson, I. Tackling challenges of a drier, hotter, more fire-prone future. Eos https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO156650 (2021).

Emmerton, C. A. et al. Severe Western Canadian wildfire affects water quality even at large basin scales. Water Res. 183, 116071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2020.116071 (2020).

Chow, A. T. S., Karanfil, T. & Dahlgren, R. A. Wildfires are threatening municipal water supplies. Eos https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO161894 (2021).

Robinne, F. N. et al. Scientists’ warning on extreme wildfire risks to water supply. Hydrol. Process. 35 (5), e14086. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.14086 (2021).

Roces-Díaz, J. V., Santín, C., Martínez-Vilalta, J. & Doerr, S. H. A global synthesis of fire effects on ecosystem services of forests and woodlands. Front. Ecol. Environ. 20 (3), 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146879 (2022).

Smith, H. G., Sheridan, G. J., Lane, P. N. J., Nyman, P. & Haydon, S. Wildfire effects on water quality in forest catchments: A review with implications for water supply. J. Hydrol. 396 (1–2), 170–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2010.10.043 (2011).

Ball, G. et al. Wildfires increasingly impact western US fluvial networks. Nat. Commun. 12, 2484. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22747-3 (2021).

Williams, A. P. et al. Growing impact of wildfire on western US water supply. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119 (10), e2114069119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2114069119 (2022).

Paul, M. J. et al. Wildfire induces changes in receiving waters: A review with considerations for water quality management. Water Resour. Res. 58 (9), e2021WR030699. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR030699 (2022).

Elliott, S. M., Hornberger, M. I., Rosenberry, D. O., Frus, R. J. & Webb, R. M. A conceptual framework to assess post-wildfire water quality: State of the science and knowledge gaps. Water Resour. Res. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023WR036260 (2024).

Rust, A. J., Saxe, S., McCray, J., Rhoades, C. C. & Hogue, T. S. Evaluating the factors responsible for post-fire water quality response in forests of the western USA. Int. J. Wildland Fire 20 (10), 769–784. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF18191 (2019).

Nichols, J. et al. Longitudinal propagation of aquatic disturbances following the largest wildfire recorded in New Mexico, USA. Nat. Commun. 15, 7143. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51306-9 (2024).

Minshall, G. W., Brock, J. T. & Varley, J. D. Wildfire and yellowstone’s stream ecosystems. Bioscience 39 (10), 707–715. https://doi.org/10.2307/1311002 (1989).

Bozek, M. A. & Young, M. K. Fish mortality resulting from delayed-effects of fire in the greater yellowstone ecosystem. Great Basin Natural. 54 (1), 91–95 (1994).

Lyon, J. P. & O’Connor, J. P. Smoke on the water: Can riverine fish populations recover following a catastrophic fire-related sediment slug?. Aust. Ecol. 33 (6), 794–806. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-9993.2008.01851.x (2008).

Silva, L. G. et al. Mortality events resulting from Australia’s catastrophic fires threaten aquatic biota. Glob. Change Biol. 26 (10), 5345–5350. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15282 (2020).

Gomez Isaza, D. F., Cramp, R. L. & Franklin, C. E. Fire and rain: A systematic review of the impacts of wildfire and associated runoff on aquatic fauna. Glob. Change Biol. 28 (8), 2578–2595. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16088 (2022).

Dahm, C. N., Candelaria-Ley, R. I., Reale, C. S., Reale, J. K. & Van Horn, D. J. Extreme water quality degradation following a catastrophic forest fire. Freshw. Biol. 60 (12), 2584–2599. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12548 (2015).

Murphy, S. F. et al. A call for strategic water-quality monitoring to advance assessment and prediction of wildfire impacts on water supplies. Front. Water 5, 1144225. https://doi.org/10.3389/frwa.2023.1144225 (2023).

Raoelison, O. D. et al. Wildfire impacts on surface water quality parameters: Cause of data variability and reporting needs. Environ. Pollut. 317, 120713. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5347 (2023).

de la Fuente, J. & Elder, D. The flood of 1997: Klamath National Forest. U.S. Forest Service Technical Report, https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/water_issues/programs/tmdl/records/region_1/2006/ref28.pdf (1998).

Department of the Interior (DOI), Klamath Dam removal overview report for the Secretary of the Interior—An assessment of science and technical information (version 1.1). U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Report, (accessed 10 October 2023); https://klamathrenewal.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/A7-Full-SDOR-accessible-022216.pdf (2012).

Hamilton, J. B., Curtis, G. L., Snedaker, S. M. & White, D. K. Distribution of anadromous fishes in the upper Klamath River watershed prior to hydropower dams—A synthesis of the historical evidence. Fisheries 30 (4), 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8446(2005)30[10:DOAFIT]2.0.CO;2 (2005).

National Research Council (NRC). Endangered and Threatened Fishes in the Klamath River Basin—Causes of Decline and Strategies for Recovery (The National Academies Press, 2004).

Stocking, R. W. & Bartholomew, J. L. Distribution and habitat characteristics of Manayunkia speciosa and infection prevalence with the parasite Ceratomyxa shasta in the Klamath River Oregon-California. J. Parasitol. 93 (1), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1645/ge-939r.1 (2007).

Bartholomew, J. L. et al. Ceratonova shasta: a cnidarian parasite of annelids and salmonids. J. Parasitol 149, 1862–1875. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031182022001275 (2022).

Ward, G.H., Armstrong, N.E., Turner, R., Zedonis, P.A. & Hetrick, N.J. Water Quality Dynamics of the Klamath River Below Iron Gate Dam: A Summary. U.S. Fish &Wildlife Service Arcata Fisheries Tech Report, 2018–2036 (accessed 10 October 2023); https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Klamath%20WQ%20TR%202018-36%20FINAL%20DRAFT%20revised%20July%2018%20%202019.pdf

Malakauskas, D. M., Willson, S. J., Wilzbach, M. A. & Som, N. A. Flow variations and substrate type affect dislodgement of the freshwater polychaete, Manayunkia speciosa. Freshwater Sci. 32 (3), 862–873. https://doi.org/10.1899/12-140.1 (2013).

Alexander, J. D., Bartholomew, J. L., Wright, K. A., Som, N. A. & Hetrick, N. J. Integrating models to predict distribution of the invertebrate host of myxosporean parasites. Freshwater Sci. 35 (4), 1263–1275. https://doi.org/10.1086/688342 (2016).

Curtis, J. A., Poitras, T. B., Bond, S. B. & Byrd, K. B. Sediment mobility and river corridor assessment for a 140 km segment of the main stem Klamath River below Iron Gate Dam (U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report, 2021). https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20201141.

Lynch, D. D. & Risley, J. C. Klamath River Basin Hydrologic Conditions Prior to the September 2002 Die-Off of Salmon and Steelhead (Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigations Report, 2003). https://doi.org/10.3133/wri034099.

Belchik, M., Hillemeier, D. & Pierce, R.M. The Klamath River fish kill of 2002; analysis of contributing factors. Yurok Tribal Fisheries Program. (accessed 10 October 2023); https://www.times-standard.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/pcffa_155.pdf

Otten, T. G., Crosswell, J. R., Mackey, S. & Dreher, T. W. Application of molecular tools for microbial source tracking and public health risk assessment of a Microcystis bloom traversing 300 km of the Klamath River. Harmful Algae 46, 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hal.2015.05.007 (2015).

Genzoli, L. & Hall, R. O. Jr. Shifts in Klamath River metabolism following a reservoir cyanobacterial bloom. Freshwater Sci. 35 (3), 795–809. https://doi.org/10.1086/687752 (2016).

Bartholomew, J. L. et al. Deconstructing dams and disease: predictions for salmon disease risk following Klamath River dam removals. Front. Ecol. Evol. 11, 1245967. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2023.1245967 (2023).

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). Klamath River Basin: A wildfire crisis strategy landscape. (accessed 10 October 10, 2023); https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/fremont-winema/news-events/?cid=fseprd1101804

Knight, C. A. et al. Land management explains major trends in forest structure and composition over the last millennium in California’s Klamath Mountains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119 (12), e2116264119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2116264119 (2022).

Lund, J., Medellin-Azuara, J., Durand, J. & Stone, K. Lessons from California’s 2012–2016 drought. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 144 (10), 04018067. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)WR.1943-5452.0000984 (2018).

Giglio, L., Justice, C., Boschetti, L. & Roy, D. MODIS/Terra+Aqua Burned Area Monthly L3 Global 500m SIN Grid V061, distributed by NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC. (accessed February 29, 2024); https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MCD64A1.061

Keeley, J. E. Fire intensity, fire severity and burn severity: A brief review and suggested usage. Int. J. Wildland Fire 18 (1), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF07049 (2009).

National Climate Data Center (NCDC). NEXRAD Q3 RADAR only reflectivity maps for KMAX station. (accessed 10 October 2023a); https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/nexradinv/

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Landslide Hazards Program: Emergency Assessment of Post-Fire Debris-Flow Hazards. (accessed 10 October 2023); https://usgs.maps.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/c09fa874362e48a9afe79432f2efe6fe

U.S. Forest Service (USFS). Burned Area Emergency Response (BAER): Interagency Burn Severity Portal. (accessed October 10, 2023); https://burnseverity.cr.usgs.gov/baer/

NOAA-USGS Debris Flow Task Force. NOAA-USGS debris-flow warning system—Final report. U.S. Geological Survey Circ. 1283, 47 (2005).

National Climate Data Center (NCDC). NOAA Weather and Climate Toolkit (WCT) App. (accessed 10 October 2023); https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/wct/

Perica, S. et al. Precipitation-Frequency Atlas of the United States.California 6 (v2.3). (accessed 10 October 2023); https://hdsc.nws.noaa.gov/hdsc/pfds/

Gartner, J. E., Cannon, S. H. & Santi, P. M. Empirical models for predicting volumes of sediment deposited by debris flows and sediment-laden floods in the transverse ranges of southern California. Eng. Geol. 176, 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2014.04.008 (2014).

Sauer, V. B. Standards for the analysis and processing of surface-water data and information using electronic methods. U.S. Geol. Survey Water-Resour. Investig. Rep. https://doi.org/10.3133/wri20014044 (2002).

Wagner, R. J., Boulger, R. W. Jr., Oblinger, C. J. & Smith, B. A. Guidelines and standard procedures for continuous water-quality monitors—Station operation, record computation, and data reporting. US Geol. Survey Tech. Methods 1 (D3), 51. https://doi.org/10.3133/tm1D3 (2006).

Rasmussen, P. P., Gray, J. R., Glysson, G. D. & Ziegler, A. C. Guidelines and procedures for computing time-series suspended-sediment concentrations and loads from in-stream turbidity-sensor and streamflow data. US Geol. Survey Tech. Methods 3 (C4), 52 (2009).

Foster, G. M. et al. Technical note–Relative variability of selected turbidity standards and sensors in use by the US geological survey. US Geol. Survey Open-File Rep. https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20211009 (2021).

U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). USGS water data for the Nation: U.S. Geological Survey National Water Information System database. (accessed 10 October 2023); https://doi.org/10.5066/F7P55KJN

Karuk Tribe: Water Quality Department: AQUARIUS Web Portal. (accessed 10 October 2023); https://waterquality.karuk.us/

Yurok Tribe: Environmental Department: AQUARIUS Web Portal. (accessed 10 October 2023); https://www.yuroktribe.org/environmental-department

Einstein, H. A. Formulas for the transportation of bed load. Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 107 (1), 561–577. https://doi.org/10.1061/TACEAT.0005468 (1942).

Heidel, S. G. The progressive lag of sediment concentration with flood waves. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 37 (1), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1029/TR037i001p00056 (1956).

Curtis, J. A. & Benthem, A. J. Baseline geomorphic map and land-surface parameters, derived from integrated topobathymetric elevation data, for the mainstem Klamath River corridor downstream of Iron Gate Dam, CA, 2018. US Geol. Survey Data Release https://doi.org/10.5066/P90KEKPH (2022).

California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) Memorandum. Preliminary Reconnaissance Habitat Impacts Assessment and Remedial Recommendations, McKinney Fire, Siskiyou County, California, Prepared by Colin R. Hughes, PG, CEG. (2022).

Lin, Y. L., Chiao, S., Wang, T. A., Kaplan, M. L. & Weglarz, R. P. Some common ingredients for heavy orographic rainfall. Weather Forecast 16, 633–660 (2001).

Clark, G. D. et al. Hysteretic response of suspended sediment in wildfire affected watersheds of the Pacific Northwest and Southern Rocky Mountains. Earth Surface Process. Landforms 50 (1), e6067. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.6067 (2025).

Malutta, S., Kobiyama, M., Chaffe, P. L. B. & Bonumá, N. B. Hysteresis analysis to quantify and qualify the sediment dynamics: state of the art. Water Sci. Technol. 81 (12), 2471–2487. https://doi.org/10.2166/wst.2020.279 (2020).

Bolade, O. & Hansen, A. T. Inferring drivers of nitrate and sediment event dynamics from hysteresis metrics for two large agricultural watersheds. Hydrol. Process. 37 (9), e14969. https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.14969 (2023).

Lewis, A. D. Silt observations of the River Tigris. Minutes Proc. Instit. Civil Eng. 212, 393–399. https://doi.org/10.1680/imotp.1921.14901 (1921).

Bull, L. J. Relative velocities of discharge and sediment waves for the River Severn, UK. Hydrol. Sci. J. 42 (5), 649–660. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626669709492064 (1997).

McDonnell, J. J. & Beven, K. Debates—The future of hydrological sciences: A (common) path forward? A call to action aimed at understanding velocities, celerities and residence time distributions of the headwater hydrograph. Water Resour. Res. 50 (6), 5342–5350. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013WR015141 (2014).

Lighthill, M. J. & Whitham, G. B. On kinematic waves I flood movement in long rivers. Pro. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A. Math. Phys. Sci. 229 (178), 281–316. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1955.0088 (1955).

Williams, G. P. Sediment concentration versus water discharge during single hydrologic events in rivers. J. Hydrol. 111 (1–4), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1694(89)90254-0 (1989).

Reid, M. A., Thoms, M. C. & Dyer, F. J. Effects of spatial and temporal variation in hydraulic conditions on metabolism in cobble biofilm communities in an Australian upland stream. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1899/0887-3593(2006)025[0756:EOSATV]2.0.CO;2 (2006).

Stumm, W. & Morgan, J. J. Aquatic Chemistry: An Introduction Emphasizing Chemical Equilibria in Natural Waters (John Wiley and Sons Inc, 1981).

Reale, J. K., Van Horn, D. J., Condon, K. E. & Dahm, C. N. The effects of catastrophic wildfire on water quality along a river continuum. Freshwater Sci. 34 (4), 1426–1442. https://doi.org/10.1086/684001 (2015).

Bernhardt, E. S. et al. Light and flow regimes regulate the metabolism of rivers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119 (8), e2121976119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2121976119 (2022).

Pennino, M. J., Kaushal, S. S., Beaulieu, J. J., Mayer, P. M. & Arango, C. P. Effects of urban stream burial on nitrogen uptake and ecosystem metabolism: implications for watershed nitrogen and carbon fluxes. Biogeochemistry 121, 247–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-014-9958-1 (2014).

Blaszczak, J. R., Delesantro, J. M., Urban, D. L., Doyle, M. W. & Bernhardt, E. S. Scoured or suffocated: Urban stream ecosystems oscillate between hydrologic and dissolved oxygen extremes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 64 (3), 877–894. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.11081 (2019).

Hall, R. O. Jr. et al. Turbidity, light, temperature, and hydropeaking control primary productivity in the Colorado River Grand Canyon. Limnol. Oceanogr. 60 (2), 512–526. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.10031 (2015).

Kirk, L., Hensley, R. T., Savoy, P., Heffernan, J. B. & Cohen, M. J. Estimating benthic light regimes improves predictions of primary production and constrains light-use efficiency in streams and rivers. Ecosystems 24, 825–839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-020-00552-1 (2021).

Newcombe, C. P. & Jensen, J. O. Channel suspended sediment and fisheries: a synthesis for quantitative assessment of risk and impact. North Am. J. Fish. Manag. 16 (4), 693–727 (1996).

Saari, G. N., Wang, Z. & Brooks, B. W. Revisiting inland hypoxia: diverse exceedances of dissolved oxygen thresholds for freshwater aquatic life. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 25, 3139–3150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-8908-6 (2018).

Chen, X., Hossain, F. & Leung, L. R. Probable maximum precipitation in the U.S Pacific Northwest in a changing climate. Water Resour. Res. 53, 9600–9622. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017WR021094 (2017).

East, A. E. & Sankey, J. B. Geomorphic and sedimentary effects of modern climate change: current and anticipated future conditions in the western United States. Rev. Geophys. 58 (4), e2019RG000692. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019RG000692 (2020).

Williams, A. P. et al. Observed impacts of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire in California. Earth’s Future 7 (8), 892–910. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EF001210 (2019).

Neary, D. G., Ryan, K. C. & DeBano, L. F. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on soils and water. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 4. Ogden, UT: US Depart. Agric. Forest Serv. Rocky Mount. Res. Stat. 42, 250. https://doi.org/10.2737/RMRS-GTR-42-V4 (2005).

Klimas, K., Hiesl, P., Hagan, D. & Park, D. Prescribed fire effects on sediment and nutrient exports in forested environments: A review. J. Environ. Qual. 49 (4), 793–811. https://doi.org/10.1002/jeq2.20108 (2020).

Young, A. M., Skelly, K. T. & Cordeira, J. M. High-impact hydrologic events and atmospheric rivers in California: An investigation using the NCEI storm events database. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 3393–3401. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL073077 (2017).

Bhattacharya, T. et al. Expansion and intensification of the North American Monsoon during the Pliocene. AGU Adv. 3 (6), e2022AV000757. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022AV000757 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not represent endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A.C. contributed to the study concept and design, data analysis and interpretation, writing, and figures. L.G. contributed to the study concept and design, data analysis and interpretation, writing, and figures. G.S.J and J.D.C. contributed to study concept and design, data collection and analysis, and review of the paper and figures. C.N.D. contributed to the study concept and design, writing, and review of the paper and figures. L.N.S. contributed to the study concept and design, data analysis and interpretation, and review of the paper and figures. J.R.O contributed to the data analysis and interpretation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Curtis, J.A., Johnson, G.S., Cahill, J.D. et al. 2022 McKinney rain-on-wildfire event, dissolved oxygen sags, and a fish kill on the Klamath River, California. Sci Rep 15, 24668 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08179-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08179-9