Abstract

Thermal energy storage with phase change materials (PCMs) is emerging as a key solution in addressing the global energy crisis, driving innovation in energy storage and management systems. This work numerically investigates the thermal performance and melting behavior of a novel composite PCM composed of paraffin wax (PW) dispersed with different weight percentages of carbon quantum dots (CQDs) in order to validate the experimental results. Latent heat curves for the prepared composite PCMs were generated numerically using computational fluid dynamics (CFD), with the input values provided from experiments and they seem to support the pattern of the experimental curves. The temperature profile and melting properties of the PCMs have also been studied. Melting temperatures of the composites indicated a maximum 5.8% discrepancy between the experimental and numerical analysis. The melting times of composites were longer than those of PW, indicating a delayed yet steady state absorption of heat during melting and improved latent heat.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The current focus of research is on increasing the use of environmentally friendly and renewable energy sources, driven by the urgent need to address the environmental crisis caused by the global rise in energy demand, which is fueled by rapid population growth and economic expansion1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8. If energy-efficiency measures are not planned and implemented, scientists predict a fifty percent spike in worldwide demand for energy by 20509. Therefore, latent heat thermal energy storage (LHTES) is drawing more and more attention as a potential remedy and to get closer to a hybrid energy system that is economically competitive10. Due to their large energy storage capacity, broad working temperature range, and potential for recycling, LHTES units, which employ phase change materials (PCMs) to store or release energy are particularly alluring11. Recently, various PCMs have been created for use in LHTES units for increasing their performance12,13.

As a result, LHTES units based on PCM are presently being investigated for several uses, including solar energy storage, nuclear power plants, heating and cooling of buildings and thermal management of electronic devices10. A plethora of outstanding review papers exist in the domain of thermal storage applications pertaining to solar or other power plant generating applications14,15,16,17,18,19,20. In low temperature thermal energy storage, PCMs are applied to flooring, walls, and ceilings. Concrete components containing PCM, wallboards impregnated with PCM, and subfloor applications are examples of actual building materials21. PCMs are extensively used in thermal management of buildings22,23,24,25. A more modern simulation study created PCM and thermal management techniques that were included into the design of office building applicable to the climate of a Saharan desert26. To reduce overheating, improve electronic components’ performance and dependability, and lengthen electronic equipment’s life, PCMs are used in electronics to control heat emitted during performance27,28,29.

However, a significant drawback of today’s PCMs is their correspondingly poor thermal conductivity values, which restrict their application in energy storage10. One of the methods that is anticipated to improve the thermophysical characteristics of the PCM, particularly its thermal conductivity involved mixing nanoparticles with the base PCM. Tariq and colleagues carried out an extensive assessment of the literature on the methods for creating nanoparticle enhanced PCMs and their uses in several fields30.

When 1% copper nanoparticles were added to the base PCM paraffin by Wu et al.31, a notable reduction of approximately 32% in melting and solidification time was obtained from experimental investigations. Additionally, there was an 18% and 14% improvement in thermal conductivity in both the liquid and solid phases, respectively. A numerical study to investigate how distributing nanoparticles affects a latent heat storage system’s performance was conducted by Gunjo et al.32. It was discovered that, in comparison to pure paraffin, adding 5% of Cu, CuO, and Al2O3 nanoparticles increased the melting rates by 10, 3.5, and 2.25 times respectively, and solidification rates by 8, 3, and 1.7 times, respectively. On the other hand, it decreased the sensible heat as well as latent heat of fusion. The melting process of a nano-PCM in a concentric cylindrical thermal energy storage system was investigated both numerically and experimentally by Alomair et al.33. They compared the melting fraction, temperature distribution, energy storage rate, and heat transfer between pure PCM and nano-PCM. Both the numerical and experimental results demonstrated that the melting rate was faster in the nano-PCM compared to pure PCM. A thermal analysis was performed on the melting of encapsulated PCM using a high-conductivity binary-eutectic alloy and low-conductivity RT27 paraffin wax by Mallya and Haussener34. The study presented the influence of thermo-physical properties, geometrical parameters, and boundary conditions on the melting process, as well as the contribution of natural convection within the encapsulated PCM. Du et al.35 constructed a 3D numerical model of latent heat storage unit with a spiral coil heat exchanger in a cylindrical shell, to replicate the melting of copper enhanced paraffin wax PCM and was thoroughly verified against experimental data. The results indicated that 19.6% of the total melting time was conserved due to the addition of nanoparticles with a little decrease in the latent heat capacity.

Although metals and metal oxides increase the thermal conductivity of PCMs, they also add weight, which lowers the density of heat storage overall. Additionally, this results in a decrease in the chemical and thermal stability of PCMs. To increase the thermal conductivity of PCMs, carbon-based fillers such as carbon nanotubes, carbon nanofibers, graphite, and graphene have been used recently. Their low density and remarkable heat conductivity are the main causes for their usage36. After reviewing several PCMs and assessing different techniques, Murali et al.37 came to the conclusion that carbon-based additive particles have better thermal conductivity than metal-based additives. Carbon-based compounds with high heat conductivity are frequently utilized as dispersants. As a result, the application of novel carbon allotropes has increased recently38.

Recent developments in nanostructured carbon materials have made it possible to use several allotropes for a wide range of electrochemical applications, including diamond, graphene, amorphous carbon, C60, carbon nanotubes, and carbon dots39. Carbon compounds have progressed from diamond, graphite, fullerenes, carbon nanotubes, graphene, and finally graphdiyne thus far. Carbon materials are categorized as 0D (carbon dots), 1D (carbon tubes/fibers), 2D (graphene), and 3D (porous carbon network) based on their dimensions40.

Upcoming nanostructures known as carbon quantum dots (CQDs) have a surface customized with organic or biomolecules and a core of carbon atoms. The size of the CQDs is usually less than 10 nm41,42. CQDs can be taken into consideration as substitutes for semiconductor quantum dots in energy transformation applications because of their low price, simplicity of synthesis, ease of customization, large quantum yield, non-toxic properties, hydrophilicity, and chemically inert nature43. Carbon dots can be utilized to create fluorescent functional composite PCMs because of their innate fluorescence properties40.

The economic viability of CQD-based PCMs is primarily determined by the synthesis process of CQDs, in addition to factors such as raw material costs, processing, composite PCM preparation, and scalability. Notably, certain CQD synthesis methods utilize renewable carbon sources, such as waste biomass and agricultural by-products, reinforcing the material’s sustainability. Plant-based materials, including fruits and vegetables, serve as eco-friendly carbon sources, making them highly suitable for CQD production. The utilization of these waste materials not only simplifies the synthesis process but also ensures cost-effectiveness and broad availability, further strengthening the case for sustainable and scalable CQD-based PCM development. CQDs exhibit promising potential for diverse applications in medicine, chemistry, food, and environmental science, thanks to their easy fabrication via green synthesis methods and the widespread availability of raw materials44. Researchers have leveraged cost-effective and eco-friendly green chemistry approaches to synthesize carbon dots from natural solid waste resources, including watermelon peel, tamarind pomelo peel, lemon peels and pineapple peel for carbon-based material production. However, the potential of sugarcane treacle as an innovative and viable raw material for carbon dot synthesis remains largely unexplored and should be further investigated. Recent studies have highlighted that sugarcane bagasse pulp and juice can serve as highly effective carbon forerunners for quantum dot synthesis, reinforcing their viability in sustainable nanomaterial development45. Sugarcane molasses has recently undergone processing via centrifugation to extract carbon dots (C-dots), which exhibit promising applications as biosensors for detecting riboflavin and tetracycline. In light of this potential, further investigation into sugarcane molasses as a novel raw material for carbon dot synthesis is strongly encouraged46. Dipcin et al.47 present an innovative CQD synthesis method that employs cost-effective reactants which are easily accessible in many of the laboratories. Green hydrothermal synthesis is distinguished by its cost-effectiveness, eco-friendliness, and high quantum yield amongst various fabrication methods48[Majid].

A key challenge in the industrial-scale synthesis of CQDs lies in the speedy evolution of raw material sourcing. Overcoming this hurdle is crucial for ensuring sustainable production. Future research should prioritize the development of synthesis methods that are more cost-effective, efficient, and novel, investigating emerging energy applications to maximize the potential of these increasingly valuable carbon materials at the same time. The large-scale synthesis of CQDs is complex and involves multiple steps, primarily due to the essential surface modifications that define their properties. Additionally, variations in natural sources and the absence of standardized protocols make it challenging to achieve homogeneous and uniform CQDs in bulk production. Despite the potential of CQDs, green synthesis from natural precursors could replace conventional synthetic methods in the future if key challenges are addressed. However, ensuring consistency, reproducibility, and scalability to industrial levels remains a significant hurdle. At present, scaling up synthesis from natural precursors while ensuring precise control over size and properties remains a challenge that necessitates further research44,49,50,51,52,53,54.

While the integration of carbon quantum dots (CQDs) improves the thermal conductivity of phase change materials (PCMs), their environmental sustainability and long-term stability remain key concerns. A thorough evaluation of these factors is essential, especially when compared to conventional PCM additives such as metals, metal oxides, and organic PCMs.

The sustainability of CQDs is primarily influenced by their synthesis techniques and the choice of raw materials. Biomass waste is a renewable, sustainable, and abundant carbon source for C-dot production. Its non-toxic nature makes it an environmentally friendly choice. In recent years, researchers have increasingly investigated biomass waste as a raw material for synthesizing C-dots55. Certain CQD synthesis methods notably incorporate renewable carbon sources, such as waste biomass and agricultural by-products, enhancing the material’s sustainability. Plant-based materials, including fruits and vegetables, provide eco-friendly carbon sources, making them excellent candidates for CQD production44. Researchers have embraced cost-effective and environmentally friendly green chemistry approaches to efficiently synthesize carbon dots from abundant natural solid waste resources. By utilizing agricultural by-products such as watermelon peel, tamarind pomelo peel, lemon peels, and pineapple peel, they not only reduce waste but also promote sustainable carbon-based material production, reinforcing the circular economy and eco-conscious material development. Recent studies have strongly emphasized the effectiveness of sugarcane bagasse pulp and juice as excellent carbon precursors for quantum dot synthesis. Their abundant availability, cost-effectiveness, and renewable nature further reinforce their crucial role in advancing sustainable nanomaterial development while promoting waste valorization and green chemistry principles45. Waste from food, agriculture, and industry is rich in functional groups like carboxyl, amino, sulfur, and hydroxyl, making it an ideal raw material for CQD fabrication and supporting a wide range of applications48.

In contrast, conventional PCM additives, such as metal nanoparticles, typically rely on non-renewable resources and require complex fabrication processes, which can lead to environmental pollution. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles is emerging in recent times. The green synthesis of nanoparticles is a growing trend in nanotechnology, developed to address challenges such as reaction complexities, high costs, and safety concerns associated with conventional methods56. The green synthesis method, known for its sustainability, cost-effectiveness, and improved biocompatibility, presents a promising alternative to traditional chemical and physical synthesis techniques. However, to fully unlock the potential of this approach, challenges such as scalability, standardization, purity, variations in plant composition, and efficient extraction processes must be addressed57.

The lifespan of a PCM depends on its thermal stability, chemical stability, and corrosion resistance (including compatibility with the container material) after multiple repeated and consistent thermal cycles. A thermally stable PCM should exhibit negligible changes in its latent heat and melting point. Therefore, ensuring thermal stability is crucial for the long-term performance of a latent heat storage system58. Metals such as Cu, Al, Ag, etc. exhibit good thermal conductivity, chemical stability in non-corrosive environments, but are prone to oxidation and corrosion in acidic or moist environments. Agglomeration or sedimentation can reduce the effectiveness over time. Non-Metal Additives such as Alumina, Silica, PANI, etc. are less prone to oxidation and more chemically stable than metals, demonstrate better dispersion in organic/inorganic PCMs compared to metals, but show poor interaction with PCM, leading to phase segregation or performance degradation over time.

CQDs hold great potential for enhancing PCMs, thanks to their nanoscale dispersion, high surface area, and superior thermal properties. Their long-term stability is determined by factors such as chemical compatibility, agglomeration resistance, and oxidation resistance. Due to their small size and functional groups, CQDs exhibit excellent dispersion, maintain chemical stability during thermal cycling, enhance both thermal conductivity and latent heat storage with minimal phase separation, and are less susceptible to oxidation than bulk metals. However, CQDs may form aggregates over long-term use, reducing their effectiveness. Additionally, potential chemical interactions with PCMs could alter their properties over time, and their stability largely depends on the synthesis method and surface functionalization.

To validate long-term thermal performance of PCMs, thermal cycling up to 300 cycles should be conducted. This testing ensures at least a year of stability for the PCM, assuming it undergoes at least one melt/freeze cycle per day59. In the study conducted by Anand et al.59, the materials considered for thermal cycling test include organic, inorganic, and composite PCMs. Only a few inorganic materials exhibited long-term stability, while most of them degraded early in the thermal cycling process. Organic materials demonstrated relatively high stability over a large number of melt/freeze cycles. Paraffin and fatty acids exhibited excellent thermal reliability.

Emeema et al.60 created innovative composite PCMs by incorporating 1%, 5%, 10%, 15%, and 20% weight percentages of CQDs in paraffin wax base PCM. The thermal conductivity of the prepared PWCQDs composite PCMs were investigated experimentally. The results revealed a significant increase in the thermal conductivity of the composite PCMs with a maximum enhancement of 97.4% for 20 wt% composite PCM. Further experimental investigations on PWCQDs composite PCMs by Emeema et al.61 revealed that the latent heat of all composite PCMs increased compared to pure PW, with the maximum enhancement reaching 65.1% for the 1% composite PCM compared to most of the studies. The melting temperature range of the composites was found to be wider than PW. Composites exhibited superb thermal stability as revealed in TGA test, excellent thermal reliability for 300 thermal cycles thus displaying tremendous potential for usage in low temperature applications.

CQDs typically exhibit superior long-term stability compared to metal additives, owing to their chemical resistance and nano-dispersion properties. However, surface functionalization may be necessary to prevent agglomeration. Given their chemical inertness and stable dispersion, CQDs show strong potential for long-term PCM applications. By overcoming environmental and stability challenges, CQD-based PCMs can emerge as a more sustainable alternative to traditional thermal energy storage materials, contributing to greener and more efficient energy solutions.

A brief literature review displaying the thermal performance of various metal oxides, graphene and CQDS has been presented in Table 1 below.

The literature survey in Table 1 displays thermal performance details of paraffin wax dispersed with different metal oxides and graphene in addition to CQDs.

The following points may be noted from the above literature survey:

-

Thermal conductivity of all the composites increased with wt% of nanoparticles added.

-

The latent heat mostly decreased with particle addition except in few cases such as Paraffin/ TiO264, RT20,RT25/Alumina, carbon Black68, Paraphene/Graphene Nanofillers74 and Paraffin/CQDs61.

-

The latent heat increase is the highest for PWCQDs composites compared to other composites.

-

From the study conducted by Emeema et al.60, PWCQDs composites displayed excellent thermal stability and superb thermal cycling characteristics.

-

Hence it can be said that PWCQDs composites stand out as brilliant composite materials when compared to oxides and graphene composites in storing thermal energy.

In this study, numerical analysis was conducted to validate the experimental results of Emeema et al.61. Latent heat curves, temperature profile, melting temperatures and melting times of the PCMs have been generated utilizing CFD with the thermophysical properties of PCMs provided from experiments and they seem to support the experimental data with little deviation. The heat transfer, thermal energy storage (TES), and PCM communities stand to gain significant insights from this work.

Experimental investigations of PWCQDs composite PCMs

The results of experimental investigations conducted on PWCQDs composite PCMs60,61 have been presented in this section.

Weight percentages and labels of composite PCMs

The PWCQDs composite PCMs were prepared by ultrasonication with the following weight percentages of CQDs in PW and labelled accordingly60. Refer Table 2.

Thermal conductivity

The thermal conductivity values for PW and composites at the phase transition temperature of 55 °C are reported, including their enhancement ratios61. Refer Table 3.

Latent heat

Latent heat values of PW and composite PCMs obtained from DSC are presented in Table 4.

Melting temperatures

The details of melting temperatures of PW and composite PCMs are presented in Table 561.

Numerical analysis

Numerical analysis using CFD was conducted on PWCQDs composite PCMs to validate the experimental results of Emeema et al.61. Ansys Fluent 2023 was used to run CFD on the 3D model of the PCM (Fig. 1). Latent heat curves, melting temperatures and melting times of the PCMs have been generated utilizing CFD.

Specification of the problem—model setup

The 3D model of the PCM can be viewed in Fig. 1. The solid PCM was placed in an enclosure that is 25 × 25 mm in size and is situated between the top and bottom plates. Copper is the material that was utilized to make both plates.

The top plate is kept at an isothermal heating state with temperature maintained between 90 and 100 °C, and the bottom plate is kept at a cold condition maintained at room temperature.

The following assumptions were made for the melting process of PCMs82,83.

-

The flow is Newtonian, laminar, incompressible and unsteady

-

Viscous dissipation effects are insignificant

-

During the process of change of phase from solid to liquid, conduction and natural convection heat transfer modes are considered for analysis. Radiation heat transfer is neglected.

-

Boussinesq approximation is followed in the analysis

-

Volume changes due to melting are disregarded

-

Thermophysical characteristics of PCM or the heat transfer fluid are not impacted by temperature. It is expected that certain properties, namely density, viscosity, and thermal conductivity, will vary linearly with temperature.

Mathematical equations

The following governing equations were considered for this study82.

Continuity equation:

Momentum equation:

Energy equation:

β = Liquid fraction, expressed as Temperature:

\({\text{T}}_{{\text{s}}}\) = PCM temperature when the last liquid content solidifies, \({\text{T}}_{{\text{l}}}\) = PCM temperature when the last solid content liquefies.

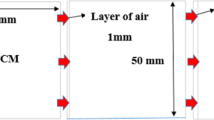

Discretization

CFD involves substituting the differential equation governing fluid flow with a series of algebraic equations known as discretization, which may then be solved numerically using a digital computer to obtain an approximate solution. Discrete volume, finite element, and finite difference methods are a few of the discretization techniques being employed84. Because of its advantages in memory consumption and solution speed particularly for large problems, high Reynolds number turbulent flows, and source term dominated flows, the finite volume method is a popular technique used in CFD software. In this study, the transient melting analysis was conducted using ANSYS Fluent 2023. The mass continuity, momentum, and energy governing equations were resolved by adopting the technique of finite volume method of discretization. The discretization details are provided in Table 6.

Grid generation

The technique of dividing the computational domain into a collection of distinct cells is known as computational mesh generation. Polyhedrons, such as tetrahedrons, hexahedrons, prisms, or pyramids, make up the grid cells. The meshing geometry of the model and PCM can be viewed in Figs. 2 and 3 respectively.

Thermophysical properties of PCMs

The thermophysical properties of pure PW and composite PCMs determined experimentally as per ASTM standards were taken as input for the numerical analysis of PCMs. The thermophysical properties of PW and composite PCMs have been listed in Table 7.

Boundary conditions

The boundary conditions are necessary for the equation system to be solved. The mathematical model must include boundary conditions. Boundaries control flow direction. The fluid and solid regions are represented by cell zones. Material and source terms are assigned to cell zones. Boundaries and internal surfaces are represented by face zones. Boundary data are assigned to face zones84. The number of cells in the grid and the grid’s fineness both affect the accuracy of the CFD solution.

The boundary conditions specified for this study are the heat flux boundary condition related to conduction heat transfer for hot plate and heat transfer coefficient related to convection heat transfer for cold plate as represented in Fig. 4.

The meshed model is processed in the ANSYS Fluent workbench, employing a pressure-based transient 2D solver to capture the melting behaviour of the nano fluid. The analysis is carried out with a time step size of 1000 and a duration of one second per time step. The set up and transient details are presented in Table 8.

Results and discussion

The parameters such as latent heat, melting times, temperature profile and behaviour of the PCMs before and after melting are discussed in this section.

Latent heat

The latent heat curves of PW and the composite PCMs generated from numerical analysis have been displayed in Figs. 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10. The latent heat curves obtained from experimental analysis have also been drawn for comparison’s sake.

Melting times of PCMs

The melting times of PCMs derived from numerical analysis are presented in Table 9.

It may be noted that the melting times of the composites are longer than PW indicating larger heat absorption by the composites compared to PW.

Temperature profile and melting characteristics

Paraffin wax

Temperature profile of paraffin wax

The melting point of PCMs is the temperature at which they transition from a solid to a liquid state. This property is vital for PCMs as it defines the temperature range within which they can efficiently store and release thermal energy. The selection of a PCM is based on its melting point to meet the needs of different applications. The appropriate PCM melting point is chosen according to the intended use, such as passive temperature regulation in buildings, cooling of electronic devices, or storage of solar energy. Figure 11 illustrates the temperature profile of the paraffin wax.

The temperature contour plot with static temperature for paraffin wax provides an in-depth visualization of the thermal distribution within the material as it undergoes the melting process. This visual tool allows us to see how efficiently heat is absorbed and distributed, with areas exposed to higher temperatures transitioning from solid to liquid as indicated by warmer colors like red and orange. Cooler colors such as blue and green, on the other hand, show regions where the PCM remains solid or less active thermally. The maximum temperature-maintained ranges from 90 to 100 °C.

Melting characteristics of paraffin wax

Figures 12 and 13 show the state of PW PCM before and after melting representing the material being melted and transitioning from solid phase to liquid phase because of the temperature increase in the sample. From the figure we can understand that the liquid fraction is gradually increasing because of the sample being heated.

Initially, the liquid fraction contour map displays the state of the PCM at the onset of the heating process. This distribution is crucial as it reveals how quickly different regions of the PCM respond to thermal input. Areas with higher initial liquid fractions are likely to react more swiftly, facilitating faster phase changes which are essential for efficient thermal management. Meanwhile, lower initial fractions suggest slower responses, potentially due to higher thermal inertia or inefficient heat conduction.

Moreover, with a latent heat of 145.35 kJ/kg and a melting time of 351 s, we can analyze the energy efficiency and the dynamics of the phase change process. This relatively short melting time indicates that paraffin wax can rapidly absorb a significant amount of heat energy, which is vital for applications requiring quick thermal response times. The liquid fraction contour at the end of the melting period, marking the conclusion of the process, identifies regions that have completely transitioned to liquid and those that remain partially melted. This end state not only assesses the uniformity and efficiency of the melting process but also informs the design of PCM systems to optimize their thermal storage and regulation capabilities.

Understanding the detailed behavior of PCM, including temperature distribution and phase transition kinetics, is indispensable for enhancing the design and application of thermal systems incorporating PCM. The incorporation of such materials into industrial and environmental applications promises advancements in energy efficiency and thermal management. Future research could further refine control over the phase change processes, enhancing PCM applicability across various sectors.

Latent heat curves of paraffin Wax

The latent heat curves obtained from the CFD analysis are shown in Fig. 5. For comparison, latent heat curves from the experiment that were acquired from DSC analysis have also been drawn. This graph is crucial for validating the thermal properties and behavior of PW PCM under varying temperatures. DSC provides empirical data by directly measuring how much heat is absorbed or released by the PCM as it undergoes temperature changes, typically during phase transitions such as melting and solidification. This measurement is critical for understanding the enthalpy changes associated with the material.

On the other hand, CFD simulations offer a theoretical perspective by using numerical methods to predict the heat flow based on material properties provided from experiments and boundary conditions. The comparison between DSC results and CFD simulations on the graph serves a dual purpose. First, it validates the CFD model by showing how closely the simulated data aligns with experimental results, which is essential for confirming the accuracy of the simulations. Second, it highlights any discrepancies between the two methods, which could indicate areas where the CFD model might need refinement or where the material properties might differ under actual conditions.

Moreover, the Temperature vs. Heat Flow graph allows us to visually interpret the thermal responsiveness of paraffin wax. Peaks or significant changes in the curve typically indicate phase changes. Observing these changes in conjunction with heat flow helps in assessing the material’s effectiveness in thermal energy storage applications. For example, a sharp peak would suggest a high latent heat capacity at the phase change temperature, which is desirable for applications requiring efficient heat management.

Incorporating both DSC and CFD data into a single graph provides a comprehensive overview of the PCM’s thermal properties. This approach not only enhances the understanding of paraffin wax as a PCM but also informs improvements in the design and application of PCM in systems where temperature control and thermal stability are crucial. The insights drawn from this graph are instrumental for engineers and researchers focusing on optimizing PCM performance in diverse applications ranging from renewable energy storage to thermal regulation in electronics. From the latent heat curve (CFD) it can be noted that the melting for PW begins at 61.2 °C (334 K) and ends at 72.8 °C (345.8 K). This can also be viewed from the colors representing the temperatures from the temperature contour plot with static temperature (Fig. 11).

Pure paraffin wax, with its high latent heat of 145.35 kJ/kg and a melting time of 351 s, exhibits uniform temperature and liquid fraction contours, indicating a consistent and predictable thermal response. The Temperature vs. Heat Flow graph for pure wax likely shows a sharp peak at the melting point, emphasizing rapid heat absorption. This behavior is ideal for applications needing quick adaptation to thermal inputs but requiring significant energy storage.

PWCQD-1 composite PCM

Temperature profile PWCQD-1

The temperature profile of PWCQD-1 composite PCM can be viewed in Fig. 14.

The temperature contour plot with static temperature for PWCQD-1provides an in-depth visualization of the thermal distribution within the material as it undergoes the melting process.

Melting characteristics of PWCQD-1

Figures 15 and 16 show the state of PWCQD-1 PCM before and after melting representing the material being melted and transitioning from solid phase to liquid phase because of the temperature increase in the sample. From the figure we can understand that the liquid fraction is gradually increasing because of the sample being heated.

Latent heat curves of PWCQD-1

The latent heat curves obtained from the CFD analysis are shown in Fig. 6. For comparison, latent heat curves from the experiment that were acquired via DSC analysis have also been drawn. This graph is crucial for validating the thermal properties and behavior of PCM under varying temperatures. DSC provides empirical data by directly measuring how much heat is absorbed or released by the PCM as it undergoes temperature changes, typically during phase transitions such as melting and solidification. This measurement is critical for understanding the enthalpy changes associated with the material. Incorporating both DSC and CFD data into a single graph provides a comprehensive overview of the PCM’s thermal properties. The insights drawn from this graph are instrumental for engineers and researchers focusing on optimizing PCM performance in diverse applications ranging from renewable energy storage to thermal regulation in electronics.

Presenting 1% CQDs increases the latent heat to 240 kJ/kg and extends the melting time to 384 s. The initial temperature and liquid fraction contours may show slight irregularities due to the CQDs disrupting the uniform thermal properties of the wax. However, the end-time contours might indicate a gradual achievement of uniformity. The Temperature vs. Heat Flow graph could display a broader temperature range during melting, suggesting a delayed but eventually steady state of heat absorption.

PWCQD-5 composite PCM

Figures 17 and 18 display the temperature profile and liquid fraction after melting of PWCQD-5 composite PCM.

With 5% CQDs, the latent heat decreases to 204.11 kJ/kg, and the melting time reduces to 376 s. The temperature contours at the initial stage could exhibit quicker heat dispersion, while the liquid fraction contours show more areas transitioning to liquid sooner than the lower concentrations. The Temperature vs. Heat Flow graph in Fig. 7 might show a lower peak but over a more extended range, indicating more efficient thermal spread with slightly reduced energy storage.

PWCQD-10 composite PCM

Figures 19 and 20 display the temperature profile and liquid fraction after melting of PWCQD-10 composite PCM.

The 10% CQD variant sees latent heat reducing further to 194.52 kJ/kg and melting time to 362 s. This concentration might demonstrate the best balance between quick melting and energy retention. Both temperature and liquid fraction contours would show a very dynamic response, with rapid and extensive melting across the composite. The Temperature vs. Heat Flow graph in Fig. 8 likely exhibits a gradual but consistent heat absorption, reflecting enhanced thermal conductivity.

PWCQD-15 and PWCQD-20 composite PCMs

Figures 21 and 22 display the temperature profile and liquid fraction after melting of PWCQD-15 composite PCM.

Figures 23 and 24 display the temperature profile and liquid fraction after melting of PWCQD-20 composite PCM.

The highest concentrations of 15% and 20% CQDs continue this trend, with the lowest latent heats of 174.27 kJ/kg and 160.53 kJ/kg respectively and the shortest melting times of 358 and 354 s, respectively. These composites are characterized by extremely efficient heat transfer capabilities as seen in very even end-time temperature and liquid fraction contours. Their Temperature vs. Heat Flow graphs in Figs. 9 and 10 likely display the broadest melting ranges with the lowest peaks, suggesting that these materials are optimal for rapid thermal management with less focus on energy storage.

Conclusions

Thermal performance and melting behavior of PWCQDs composite PCMs have been simulated with CFD analysis. A satisfactory simulation is suggested by the latent heat curves produced by numerical analysis, which match the pattern of the experimental curves.

-

A comparison was made between the melting temperatures of PWCQDs composite PCMs derived by numerical analysis and the corresponding values obtained through experimental investigation. Melting temperatures obtained by numerical analysis showed a maximum deviation of 5.8% from the experimental values.

-

Thus, the experimental analysis of thermal performance of PWCQDs composite PCMs has been validated by numerical analysis using CFD with little deviation.

-

Consequently, the PWCQDs composite PCMs categorically satisfy the requirements for their employment in low temperature thermal energy storage applications with an aim to improve the thermal performance of LHTES systems.

-

It is therefore highly advised to employ PWCQDs composite PCMs for thermal energy storage in low-temperature LHTES systems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Du, K., Calautit, J., Wang, Z., Wu, Y. & Liu, H. A review of the applications of phase change materials in cooling, heating and power generation in different temperature ranges. Appl. Energy 220, 242–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.03.005 (2018).

Plytaria, M. T., Bellos, E., Tzivanidis, C. & Antonopoulos, K. A. Numerical simulation of a solar cooling system with and without phase change materials in radiant walls of a building. Energy Convers. Manage. 188, 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2019.03.042 (2019).

Liu, J., Mei, C., Wang, H., Shao, W. & Xiang, C. Powering an island system by renewable energy: A feasibility analysis in the Maldives. Appl. Energy 227, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.10.019 (2018).

Peker, M., Kocaman, A. S. & Kara, B. Y. Benefits of transmission switching and energy storage in power systems with high renewable energy penetration. Appl. Energy 228, 1182–1197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.07.008 (2018).

Zia, M. F., Elbouchikhi, E. & Benbouzid, M. Microgrids energy management systems: A critical review on methods, solutions, and prospects. Appl. Energy 222, 1033–1055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.04.103 (2018).

Husein, M. & Chung, I. Y. Optimal design and financial feasibility of a university campus microgrid considering renewable energy incentives. Appl. Energy 228, 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.05.036 (2018).

Zhu, C., Li, B., Yan, S., Luo, Q. & Li, C. Experimental research on solar phase change heat storage evaporative heat pump system. Energy Convers. Manage. 229, 113683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113683 (2021).

Wu, D. et al. Experimental investigation on the hygrothermal behavior of a new multilayer building envelope integrating PCM with bio-based material. Build. Environ. 201, 107995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2021.107995 (2021).

Marin, P. et al. Energy savings due to the use of PCM for relocatable lightweight buildings passive heating and cooling in different weather conditions. Energy Build. 129, 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2016.08.007 (2016).

Amidu, M. A., Ali, M., Alkaabi, A. K. & Addad, Y. A critical assessment of nanoparticles enhanced phase change materials (NePCMs) for latent heat energy storage applications. Sci. Rep. 13, 7829. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-34907-0 (2023).

Faraji, H., Benkaddour, A., Oudaoui, K., El Alami, M. & Faraji, M. Emerging applications of phase change materials: A concise review of recent advances. Heat Transf. 50, 1443–1493. https://doi.org/10.1002/htj.21938 (2021).

Liu, M., Zhang, X., Ji, J. & Yan, H. Review of research progress on corrosion and anti-corrosion of phase change materials in thermal energy storage systems. J. Energy Stor. 63, 107005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.107005 (2023).

Rogowski, M. & Andrzejczyk, R. Recent advances of selected passive heat transfer intensification methods for phase change material-based latent heat energy storage units: A review. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 144, 106795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2023.106795 (2023).

Liu, M., Saman, W. & Bruno, F. Review on storage materials and thermal performance enhancement techniques for high temperature phase change thermal storage systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16, 2118–2132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2012.01.020 (2012).

Alnaimat, F. & Rashid, Y. Thermal energy storage in solar power plants: A review of the materials, associated limitations, and proposed solutions. Energies 12, 4164. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12214164 (2019).

Pascual, S., Lisbona, P. & Romeo, L. M. Thermal energy storage in concentrating solar power plants: A review of European and North American R&D projects. Energies 15, 8570. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15228570 (2022).

Khan, M. I., Asfand, F. & Al-Ghamdi, S. G. Progress in research and development of phase change materials for thermal energy storage in concentrated solar power. Appl. Therm. Eng. 219, 119546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2022.119546 (2023).

Bashir, M. A. & Giovannelli, A. Phase change materials (PCMs) applications in solar energy systems. in Phase Change Materials for Heat Transfer 129–153 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-91905-0.00004-6

Jayathunga, D. S., Karunathilake, H. P., Narayana, M. & Witharana, S. Phase change material (PCM) candidates for latent heat thermal energy storage (LHTES) in concentrated solar power (CSP) based thermal applications-A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 189, 113904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2023.113904 (2024).

Pakalka, S., Donėlienė, J., Rudzikas, M., Valančius, K. & Streckienė, G. Development and experimental investigation of full-scale phase change material thermal energy storage prototype for domestic hot water applications. J. Energy Stor. 80, 110283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2023.110283 (2024).

Khudhair, A. M. & Farid, M. A review on energy conservation in building applications with thermal storage by latent heat using phase change materials. Therm. Energy Stor. Phase Change Mater. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780367567699 (2021).

Kasaeian, A., Pourfayaz, F., Khodabandeh, E. & Yan, W. M. Experimental studies on the applications of PCMs and nano-PCMs in buildings: A critical review. Energy Build. 54, 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enbuild.2017.08.037 (2017).

Smaisim, G. F., Abed, A. M., Hadrawi, S. K. & Shamel, A. Modeling and thermodynamic analysis of solar collector cogeneration for residential building energy supply. J. Eng. 1, 6280334. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6280334 (2022).

Hai, T. et al. Simulation of solar thermal panel systems with nanofluid flow and PCM for energy consumption management of buildings. J. Build. Eng. 58, 104981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104981 (2022).

Hayatina, I., Auckaili, A. & Farid, M. Review on the life cycle assessment of thermal energy storage used in building applications. Energies 16, 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16031170 (2023).

Sarri, A., Al-Saadi, S. N., Arıcı, M., Bechki, D. & Bouguettaia, H. Architectural design strategies for enhancement of thermal and energy performance of PCMs-embedded envelope system for an office building in a typical arid Saharan climate. Sustainability. 15, 1196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021196 (2023).

Vali, P. S. N. & Murali, G. Experimental study on thermal management of nano enhanced phase change material integrated battery pack. ASME J. Heat Mass Transf. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4064155 (2024).

Masthan Vali, P. S. & Murali, G. Battery thermal management system on trapezoidal battery pack with liquid cooling system utilizing phase change material. ASME J. Heat Mass Transf. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4063355 (2024).

Arshad, A. et al. Thermal performance of a phase change material-based heat sink in presence of nanoparticles and metal-foam to enhance cooling performance of electronics. J. Energy Stor. 48, 03882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2021.103882 (2022).

Tariq, S. L., Ali, H. M., Akram, M. A., Janjua, M. M. & Ahmadlouydarab, M. Nanoparticles enhanced phase change materials (NePCMs): A recent review. Appl. Therm. Eng. 176, 115305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.115305 (2020).

Wu, S. Y., Wang, H., Xiao, S. & Zhu, D. S. An investigation of melting/freezing characteristics of nanoparticle-enhanced phase change materials. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 170, 1127–1131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-011-2080-x (2012).

Gunjo, D. G., Jena, S. R., Mahanta, P. & Robi, P. S. Melting enhancement of a latent heat storage with dispersed Cu, CuO and Al2O3 nanoparticles for solar thermal application. Renew. Energy 121, 652–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2018.01.013 (2018).

Alomair, M., Alomair, Y., Tasnim, S., Mahmud, S. & Abdullah, H. Analyses of bio-based nano-PCM filled concentric cylindrical energy storage system in vertical orientation. J. Energy Stor. 20, 380–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2018.10.004 (2018).

Mallya, N. & Haussener, S. Buoyancy-driven melting and solidification heat transfer analysis in encapsulated phase change materials. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 164, 120525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2020.120525 (2021).

Du, R., Li, W., Xiong, T., Yang, X., Wang, Y. & Shah, K. W. Numerical investigation on the melting of nanoparticle-enhanced PCM in latent heat energy storage unit with spiral coil heat exchanger. in Building Simulation, vol. 12, 869–879 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12273-019-0527-3

Wang, J., Xie, H., Xin, Z., Li, Y. & Chen, L. Enhancing thermal conductivity of palmitic acid based phase change materials with carbon nanotubes as fillers. Sol. Energy 84, 339–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2009.12.004 (2010).

Murali, G., Sravya, G. S., Jaya, J. & Vamsi, V. N. A review on hybrid thermal management of battery packs and it’s cooling performance by enhanced PCM. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 150, 11513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111513 (2021).

Jebasingh, B. E. & Arasu, A. V. A comprehensive review on latent heat and thermal conductivity of nanoparticle dispersed phase change material for low-temperature applications. Energy Stor. Mater. 54, 52–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ensm.2019.07.031 (2020).

Georgakilas, V., Perman, J. A., Tucek, J. & Zboril, R. Broad family of carbon nanoallotropes: Classification, chemistry, and applications of fullerenes, carbon dots, nanotubes, graphene, nanodiamonds, and combined superstructures. Chem. Rev. 115, 4744–4822. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr500304f (2015).

Chen, X. et al. Carbon-based composite phase change materials for thermal energy storage, transfer, and conversion. Adv. Sci. 9, 2001274. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202001274 (2021).

Molaei, M. J. Carbon quantum dots and their biomedical and therapeutic applications: A review. RSC Adv. 19, 6460–6481. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8RA08088G (2019).

Molaei, M. J. A review on nanostructured carbon quantum dots and their applications in biotechnology, sensors, and chemiluminescence. Talanta 196, 1456–1478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2018.12.042 (2019).

Molaei, M. J. The optical properties and solar energy conversion applications of carbon quantum dots: A review. Sol. Energy 196, 549–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solener.2019.12.036 (2020).

Rasal, A. S. et al. Carbon quantum dots for energy applications: A review. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 4(7), 6515–6541. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.1c01372 (2021).

Pandiyan, S. et al. Biocompatible carbon quantum dots derived from sugarcane industrial wastes for effective nonlinear optical behavior and antimicrobial activity applications. ACS Omega 5(47), 30363–30372. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.0c03290 (2020).

Huang, G. et al. Photoluminescent carbon dots derived from sugarcane molasses: Synthesis, properties, and applications. RSC Adv. 7(75), 47840–47847. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7RA09002A (2017).

Dipcin, B., Guvendiren, B., Birdogan, S. & Tanoren, B. A novel carbon quantum dot (CQD) synthesis method with cost-effective reactants and a definitive indication: Hot bubble synthesis (HBBBS). J. Sci.: Adv. Mater. Dev. 9(4), 100797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsamd.2024.100797 (2024).

Majid, A. et al. The advanced role of carbon quantum dots in nano-food science: Applications, bibliographic analysis, safety concerns, and perspectives. C 11(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/c11010001 (2024).

Qureshi, Z. A., Dabash, H., Ponnamma, D. & Abbas, M. K. G. Carbon dots as versatile nanomaterials in sensing and imaging: Efficiency and beyond. Heliyon https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31634 (2024).

Jose, J., Rangaswamy, M., Shamnamol, G. K. & Greeshma, K. P. A short review on natural precursors-plant-based fluorescent carbon dots for the targeted detection of metal ions. Sustain. Chem. Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scenv.2024.100114 (2024).

Salvi, A., Kharbanda, S., Thakur, P., Shandilya, M. & Thakur, A. Biomedical application of cabon quantum dots: A review. Carb. Trends https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cartre.2024.100407 (2024).

Khan, R. et al. Progress and obstacles in employing carbon quantum dots for sustainable wastewater treatment. Environ. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2024.119671 (2024).

Usman, M. & Cheng, S. Recent trends and advancements in green synthesis of biomass-derived carbon dots. Eng 5(3), 2223–2263. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng5030116 (2024).

Kohli, H. K. & Parab, D. Green synthesis of carbon quantum dots and applications: An insight. Next Mater. 8, 100527. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nxmate.2025.100527 (2025).

Kang, C., Huang, Y., Yang, H., Yan, X. F. & Chen, Z. P. A review of carbon dots produced from biomass wastes. Nanomaterials 10(11), 2316. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10112316 (2020).

Jamkhande, P. G., Ghule, N. W., Bamer, A. H. & Kalaskar, M. G. Metal nanoparticles synthesis: An overview on methods of preparation, advantages and disadvantages, and applications. J. Drug Del. Sci. Technol. 53, 101174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2019.101174 (2019).

Pechyen, C., Tangnorawich, B., Toommee, S., Marks, R. & Parcharoen, Y. Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles, characterization, and biosensing applications. Sens. Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jddst.2019.101174 (2024).

Rathod, M. K. & Banerjee, J. Thermal stability of phase change materials used in latent heat energy storage systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 18, 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2012.10.022 (2013).

Anand, A., Shukla, A., Kumar, A., Buddhi, D. & Sharma, A. Cycle test stability and corrosion evaluation of phase change materials used in thermal energy storage systems. J. Energy Stor. 39, 102664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2021.102664 (2021).

Janumala, E., Govindarajan, M., Bomma, R. V. R. & Chinnasamy, S. Investigations on a novel composite phase change material comprising paraffin wax and CQDs for thermal conductivity enhancement. Therm. Sci. 00, 217–217. https://doi.org/10.2298/TSCI220911217J (2023).

Janumala, E., Govindarajan, M., Bomma, R. V. R. & Chinnasamy, S. Investigations on a novel composite phase change material comprising paraffin wax and CQD for thermal conductivity enhancement. Therm. Sci. 27(6 Part B), 4747–4755. https://doi.org/10.2298/TSCI220911217J (2023).

Ho, C. J. & Gao, J. Y. Preparation and thermophysical properties of nanoparticle-in-paraffin emulsion as phase change material. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 36(5), 467–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2009.01.015 (2009).

Jesumathy, S., Udayakumar, M. & Suresh, S. Experimental study of enhanced heat transfer by addition of CuO nanoparticle. Heat Mass Transf. 48, 965–978. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00231-011-0945-y (2012).

Ali, A. H., Ibrahim, S. I., Jawad, Q. A., Jawad, R. S. & Chaichan, M. T. Effect of nanomaterial addition on the thermophysical properties of Iraqi paraffin wax. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 15, 100537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csite.2019.100537 (2019).

Wang, J., Xie, H., Guo, Z., Guan, L. & Li, Y. Improved thermal properties of paraffin wax by the addition of TiO2 nanoparticles. Appl. Therm. Eng. 73(2), 1541–1547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2014.05.078 (2014).

Chaichan, M. T., Kamel, S. H. & Al-Ajeely, A. N. M. Thermal conductivity enhancement by using nano-material in phase change material for latent heat thermal energy storage systems. Saussurea 5(6), 48–55 (2015).

Şahan, N., Fois, M. & Paksoy, H. Improving thermal conductivity phase change materials: A study of paraffin nanomagnetite composites. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 137, 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.solmat.2015.01.027 (2015).

Nourani, M., Hamdami, N., Keramat, J., Moheb, A. & Shahedi, M. Thermal behavior of paraffin-nano-Al2O3 stabilized by sodium stearoyl lactylate as a stable phase change material with high thermal conductivity. Renew. Energy 88, 474–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2015.11.043 (2016).

Colla, L., Fedele, L., Mancin, S., Danza, L. & Manca, O. Nano-PCMs for enhanced energy storage and passive cooling applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 110, 584–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.03.161 (2017).

Shalaby, S. M., Abosheiash, H. F., Assar, S. T. & Kabeel, A. E. Improvement of thermal properties of paraffin wax as latent heat storage material with direct solar desalination systems by using aluminum oxide nanoparticles. No. June, pp. 28–30 (2018).

Jesumathy, P. S. Latent heat thermal energy storage system. in Phase Change Materials and Their Applications (IntechOpen, 2018). https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.77177

Kumar, P. M., Anandkumar, R., Sudarvizhi, D., Mylsamy, K. & Nithish, M. Experimental and theoretical investigations on thermal conductivity of the paraffin wax using CuO nanoparticles. Mater. Today: Proc. 22, 1987–1993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.03.164 (2020).

Kumar, P. M., Mylsamy, K., Prakash, K. B., Nithish, M. & Anandkumar, R. Investigating thermal properties of nanoparticle dispersed paraffin (NDP) as phase change material for thermal energy storage. Mater. Today: Proc. 45, 745–750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.02.800 (2021).

Goli, P. et al. Graphene-enhanced hybrid phase change materials for thermal management of Li-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 248, 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.08.135 (2014).

Liu, C., Zhang, X., Lv, P., Li, Y. & Rao, Z. Experimental study on the phase change and thermal properties of paraffin/carbon materials based thermal energy storage materials. Phase Trans. 90(7), 717–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411594.2016.1277219 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Yue, W., Zhang, S., Huang, S. &Liu, J. Experimental investigation of paraffin wax with graphene enhancement as thermal management materials for batteries. in 2016 17th International Conference on Electronic Packaging Technology (ICEPT) 1401–1405 (IEEE, 2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICEPT.2016.7583385

Liu, X. & Rao, Z. Experimental study on the thermal performance of graphene and exfoliated graphite sheet for thermal energy storage phase change material. Thermochim. Acta 647, 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tca.2016.11.010 (2017).

Safaei, M. R., Goshayeshi, H. R. & Chaer, I. Solar still efficiency enhancement by using graphene oxide/paraffin nano-PCM. Energies 12(10), 2002. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12102002 (2019).

Kumar, K., Sharma, K., Verma, S. & Upadhyay, N. Experimental investigation of graphene-paraffin wax nanocomposites for thermal energy storage. Mater. Today: Proc. 18, 5158–5163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2019.07.513 (2019).

Ali, M. A., Viegas, R. F., Kumar, M. S., Kannapiran, R. K. & Feroskhan, M. Enhancement of heat transfer in paraffin wax PCM using nano graphene composite for industrial helmets. J. Energy Stor. 26, 100982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.est.2019.100982 (2019).

Li, W., Dong, Y., Zhang, X. & Liu, X. Preparation and performance analysis of graphite additive/paraffin composite phase change materials. Processes 7(7), 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr7070447 (2019).

Waqas, H. et al. Enhancing the performance of thermal energy storage by adding nano-particles with paraffin phase change materials. Nanotechnol. Rev. 13, 20230180. https://doi.org/10.1515/ntrev-2023-0180 (2024).

Youssef, W., Ge, Y. T. & Tassou, S. A. CFD modelling development and experimental validation of a phase change material (PCM) heat exchanger with spiral-wired tubes. Energy Convers. Manage. 157, 498–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enconman.2017.12.036 (2018).

Zawawi, M. H., Saleha, A., Salwa, A., Hassan, N. H., Zahari, N. M., Ramli, M. Z. & Muda, Z. C. A review: Fundamentals of computational fluid dynamics (CFD). in AIP conference proceedings. 2030 (2018). AIP Conf. Proc. 2030 020252 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5066893

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2024-32).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.M, J.E, B.V.R, P.S.N.M.V developed the idea and conducted the experiments, G.M wrote the manuscript, E.P.V, M.M, M.A, T.B.R, S.R edited the manuscript, all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Murali, G., Emeema, J., Reddi, B.V. et al. Study of thermal performance and melting behaviour of a novel paraffin wax-carbon quantum Dots PCMs. Sci Rep 15, 30066 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08312-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08312-8