Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are a leading cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide, with a significant burden in Iran. Limited research has investigated patterns of modifiable CVDs risk factors in Iran. This study aims to address this gap by identifying distinct patterns of modifiable CVDs risk factors among adult aged + 40 and explore the relationship between demographic characteristics and risk factor patterns. This study was conducted using data from the Kherameh cohort study. The participants consisted of 9,422 individuals aged 40–70 years without CVDs. Latent Class Analysis (LCA) was used to identify latent classes of modifiable CVD risk factors. Multinomial logistic regression assessed the relationship between latent classes (LCs) and demographic variables. Three latent classes were identified as follows: low-risk (42%), clinical-risk (52%) and lifestyle-risk (6%) classes. Female gender (Adjusted OR: 13.48, 95% CI: 11.81–15.39), older age (Adjusted OR: 1.16, 95% CI: 0.99-1.35) and rural residence (Adjusted OR: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.67–0.86) had a greater risk of being in clinical-risk class compared to the low-risk class. Moreover, individuals of Fars ethnicity exhibited a significantly elevated risk of being classified in the clinical risk class for CVD (Adjusted OR: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.14–1.43) and they demonstrated a markedly higher risk of belonging to the lifestyle risk class (Adjusted OR: 1.51, 95% CI: 1.11–2.07). The study identified distinct latent classes of modifiable CVD risk factors and provided insights into their associations with demographic characteristics. Understanding risk patterns is crucial for developing effective preventive strategies and providing appropriate health protocols.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are a major public health concern worldwide, causing a significant portion of deaths and disabilities1. Ischemic heart disease (IHD) and stroke are the leading contributors to CVD-related deaths, with developing countries experiencing higher rates2. In Iran, CVDs are the leading cause of death and disability, with a prevalence exceeding 9% in some regions3,4,5. The burden of CVDs in Iran is expected to double by 2025 compared to 2005, particularly among individuals over 306.

Risk factors for CVDs can be categorized into non-modifiable and modifiable factors. Non-modifiable factors include age, gender, ethnicity, and family history. Modifiable risk factors can be further divided into three domains: clinical/biological factors (e.g., obesity, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia), psychosocial factors (e.g., anxiety, stress, depression), and behavioral/lifestyle factors (e.g., sleep patterns, alcohol consumption, smoking, diet, physical activity)7,8,9,10,11.

Understanding the patterns of CVD risk factors within specific populations is crucial for developing effective preventive interventions. Latent Class Analysis (LCA) is an advanced statistical method that can identify subgroups of individuals with similar risk factor profiles. Although several studies have been carried out concerning risk factors for CVD in Iran, few of these used LCA to assess the patterning of these risk factors. It therefore creates a glaring need for in-depth analysis in order to unravel the hidden patterns and provide a background for efficient preventive measures. Thereby, the obtained patterns in Kherameh will be important not only to this population but also to others having similar characteristics in terms of risks.

This study aims to identify distinct patterns of well-established modifiable CVD risk factors among adults aged 40–70 years in the Kherameh cohort study. These risk factors include diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, high blood total cholesterol, abdominal obesity, disturbed sleep, smoking status, and alcohol consumption. The study will further characterize the most prominent risk factors within each identified pattern and explore the relationship between demographic characteristics and these risk factor patterns.

Methods

Study design

The present findings were extracted from a research project approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (IR.SUMS.SCHEANUT.REC.1402.052) and informed consent was obtained from all the participants. This cross-sectional, analytical study utilized baseline data from the Kherameh cohort study, a population-based sub-cohort of the Prospective Epidemiological Research Studies in Iran (PERSIAN). The PERSIAN Cohort Study, Launched in 2014, encompasses 18 geographical regions across Iran and includes all major Iranian ethnicities and its rationale, goals, and design have already been published12. Kherameh, a city in southern Fars province with a population of 61,580, contributes to this study with 10,663 individuals aged 40–70 years. Due to missing values, 10,611 participants were included in the current analysis12.

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria mirrored those of the Kherameh cohort study: participants aged 40–70 years, as behaviors and health outcomes like chronic diseases are well-established in this group. Additionally, participants had to reside in the Kherameh area for at least 9 months prior to enrollment to account for environmental and cultural influences. Exclusion criteria included untreated acute illnesses, diagnosed mental health conditions, unwillingness to participate, and inability to attend clinic examinations. Additionally, individuals with a previous diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (CVD), specifically including ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and cerebrovascular accident (CVA), to focus on assessing CVD risk in those without prior heart disease.

CVD risk indicators

Our focus is on specific subtypes of CVD including ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and cerebrovascular accident (CVA). Our analysis included commonly used CVD risk indicators such as hypertension, high blood total cholesterol, DM, obesity, and smoking, based on models like the Framingham risk score13,14. Additional indicators included abnormal sleep and alcohol consumption8,11. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 85 mmHg15,16,17. High blood cholesterol was defined as total cholesterol level ≥ 250 mg/dL18. Abdominal obesity was defined as waist circumference ≥ 102 cm in men and ≥ 88 cm in women19. DM, smoking, and alcohol consumption were coded as binary variables. Disturbed sleep was defined as sleep duration ≥ 9 h or ≤ 5 h20,21.

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics included age (40–49, 50–59, and 60–70 years), gender, ethnicity (Fars and others), employment status (employed or unemployed), area of residence (urban or rural), education level (illiterate, diploma or lower diploma, academic degree), and socioeconomic status (low, medium, or high). Socioeconomic status was determined using principal component analysis (PCA) based on factors like house ownership, house size, number of bathrooms, car ownership and price, travel frequency, and ownership of household items.

Statistical methods

To understand how modifiable CVD risk factors cluster, we used latent class analysis (LCA) to identify distinct patterns of these factors22. Model evaluation criteria included Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), entropy, and interpretability. Lower BIC and AIC values indicate better model fit23 , while higher entropy values indicate better classification24. Multi-nominal logistic regression was used to examine the relationship between identified risk groups and personal variables. LCA was performed using R software version 4.3.1, and StataMP17 was used for regression analysis.

Results

Description

The present study started with 10,611 participants. After excluding 1,189 subjects with CVDs at baseline, 9,422 subjects were included in the analysis. Among the 9,422 participants, 1,917 (20.3%) had hypertension, 962 (10.2%) had high blood total cholesterol, 1,335 (14.2%) had DM, and 5,140 (54.6%) had abdominal obesity. Additionally, 1,991 subjects (21%) had a disturbed sleep, 2,392 (25%) were smokers, and 351 (4%) consumed alcohol (Table 1).

Number of latent classes

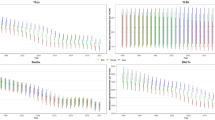

The variables hypertension, high blood Total cholesterol, DM, abdominal obesity, disturbed sleep, smoking, and alcohol consumption were used as indicator variables in the model. To determine the best-fitting number of latent classes (LCs), we began with a two-class model and incrementally increased the number of classes up to four. Model evaluation criteria included BIC, AIC, entropy, and interpretability. Based on these criteria, three LCs were selected as the best fit for individuals at risk of developing CVD (Table 2).

Identified classes labeling

The largest class was Class 1 (52%), followed by Class 3 (42%) and Class 2 (6%). The predicted probabilities of observed variables for each class are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 1.

-

Class 1 (Clinical Risk): High probability of clinical risks but relatively healthy lifestyle.

-

Class 2 (Lifestyle Risk): Unhealthy lifestyle with low probability of clinical risks.

-

Class 3 (Low Risk): Relatively healthy lifestyle with low probability of clinical risks.

The relationship between identified risk groups with demographic variables and socioeconomic status

The findings indicated significant associations between risk group membership and various demographic and socioeconomic factors:

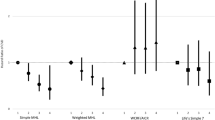

The odds of belonging to the clinical risk group compared to the low-risk group were 13.5 times higher for women than men (Adjusted OR: 13.48, 95% CI: 11.81–15.39).

The odds of being in the clinical risk group versus the low-risk group were 24% higher for rural residents compared to urban residents (Adjusted OR: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.67–0.86).

For the 60–70 age group, the odds of clinical risk group membership compared to the low-risk group were 16% higher than for the 40–49 and 50–59 age groups (Adjusted OR: 1.16, 95% CI: 0.99-1.35).

The odds of being in the clinical risk group compared to the lifestyle risk group (Adjusted OR: 1.28, 95% CI: 1.14–1.43) and the low-risk group (Adjusted OR: 1.51, 95% CI: 1.11–2.07) were 28% and 50% higher, respectively, for the Fars ethnicity compared to other ethnicities (Table 4).

Discussion

The current study utilized baseline data from the Kherameh cohort to identify patterns of CVDs risk factors and their relation to demographic characteristics using the LCA model. In this study we found the following: Firstly, three LCs of modifiable risk factors for CVDs were recognized (i.e. clinical risk class, lifestyle risk class, and low risk class). Secondly, Female gender, older age and rural residence had a greater risk of being in clinical-risk class compared to the low-risk class. Lastly, individuals of Fars ethnicity revealed a significantly elevated risk of being classified in the clinical risk class and they recognized an obviously higher risk of belonging to the lifestyle risk class.

Patterns of modifiable CVD risk factors

Three LCs of modifiable risk factors for CVDs were identified: 1. Clinical Risk Class: High probability of DM, hypertension, central obesity, and high blood total cholesterol, 2. Lifestyle Risk Class: Unhealthy lifestyle including disturbed sleep, smoking, and alcohol consumption, 3. Low Risk Class: Relatively healthy lifestyle with a low probability of clinical risks. Based on three LCs (i.e. clinical risk, life-style risk and low risk), the clinical risk class was the largest, followed by the low risk class. To our knowledge, limited studies have used LCA to identify LCs of CVD. Different criteria used by researchers make direct comparisons challenging. One such study, conducted on 8,218 UK adults over 50 years, identified four CVD risk factor classes: low risk, high risk, clinical risk, and lifestyle risk25.

Our findings showed that modifiable CVD risk factors divided into two main classes: clinical and lifestyle risks. Individuals with hypertension often had other CVD-related clinical conditions, and sleep disturbances were associated with other lifestyle risks such as smoking and alcohol consumption. This is consistent with previous studies indicating a high prevalence of co-occurring conditions like diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity, as well as the clustering of health behaviors26,27.

The relationship between identified risk groups with demographic variables and socioeconomic status

We found that membership in the clinical risk class was more common among individuals aged 60–70 years. This aligns with studies showing that the average age in high-risk groups for CVD is around 69 years28. One of the reasons why the risk of CVD increases with age can be due to a combination of physiological changes and the accumulation of risk factors over time. It was also stated in the previous study29, the elderly population are especially susceptible to cardiovascular diseases. Age is an independent risk factor for CVD in adults, these risks are compounded by other factors including obesity and diabetes. These complex factors are known as age-related CVD risk factors.

Our results also indicated that clinical risk membership was significantly higher in women than men, which is consistent with some studies14,30,31,32. As mentioned, gender is another potential risk factor in older adults, with older women reported to be at greater risk for CVD than age-matched men. However, in both men and women, the risks associated with CVD increase with age, and these risks may be related to a general decline in sex hormones, mainly estrogen and testosterone29.

Interestingly, our study found that the clinical risk class was more prevalent in rural areas, contrary to many studies that report higher prevalence of CVD risk factors in urban areas33,34,35. But studies similar36,37 to ours show a higher prevalence of clinical CVD risk factors in rural people. Several factors may contribute to the higher prevalence of CVD risk factors in rural areas, including inequities in access to health care, low socio-economic status and level of education in rural areas and a lack of grocery stores that offer affordable and healthy foods, But in general, the exact reasons for these rural–urban health inequalities are unclear and need further investigation.

A previous study38 has shown that there is heterogeneity and diverse distribution of known lifestyle-related risk factors for heart disease among major Iranian ethnic groups. In our study, Fars ethnicity was more likely to be in the clinical and lifestyle risk classes compared to other ethnicities, which supports findings from other research39. This ethnic difference in CVD risks can be due to differences in diet, physical activity, smoking, and other lifestyle behaviors among ethnic groups, which are closely related to the development of hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and dyslipidemia. Also, differences in socioeconomic status, education level, and access to health care resources among ethnic communities could be other reasons for this result. Additionally, potential genetic and biological differences between ethnic groups and the role of cultural practices, traditions, and environmental exposures unique to different ethnic communities may influence CVD risk.

In this study, no relationship was observed between class membership with employment status, education level, marital status, and SES. Meanwhile, a study conducted on 2,380 cases from five cities of Stanford investigated the independent relation between education level and income with a set of CVD risk factors, such as cigarette smoking, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol and HDL, and found that lower education and income were associated with higher risk of CVD development40. Studies on lifestyle-related CVD risk factors with SES have shown contradictory results, which may depend on the definition of SES and lifestyle factors as well as population characteristics41. It should be noted that previous studies have shown contradictory results regarding the relation between marital status and CVD risk39,42,43.

Strengths and limitations

This study is the first to examine the latent structure of modifiable CVD risk factors in Iran using Latent Class Analysis (LCA), a method with distinct advantages over traditional clustering techniques. LCA, as a cross-sectional latent variable mixture modeling approach, identifies subgroups that are internally homogeneous and externally heterogeneous44,45, using maximum likelihood estimation to ensure robust classification46. It also provides fit statistics47, which allow for the selection of the most appropriate model48and hypothesis testing, as well as information on the probability of individuals belonging to specific classes49,50. These features make LCA particularly suitable for analyzing complex, categorical data such as the risk factors in our study.

Moreover, this research was conducted with a large sample size and high accuracy, providing a strong basis for the identification of latent classes of modifiable CVD risk factors. However, several limitations should be noted:

The analysis included only individuals aged 40 years or older, making it unclear if the same patterns occur in younger age groups. Additionally, the cross-sectional design prevents establishing causality. Future research should explore how clusters of CVD risk factors evolve over time and which changing behavioral or clinical risk patterns pose the highest risk for CVD.

The cohort was derived from the Kherameh region, which has a rural context and specific demographic characteristics. These unique attributes may limit the generalizability of our findings to other populations, particularly urban settings or populations with different socioeconomic and cultural profiles. Future studies should replicate this analysis in other regional and demographic contexts to validate and expand the patterns identified in this study. This includes conducting similar analyses in urban and mixed populations to test the robustness and applicability of the findings in diverse settings.

Our focus on specific subtypes of CVD, including ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and cerebrovascular accident (CVA), may also limit the generalizability of our findings to all subtypes of CVD. This specificity means that the risk factor patterns identified might not fully represent other forms of cardiovascular disease not explicitly included in our definition.

Future studies should consider longitudinal designs to track the evolution of CVD risk factors over time and examine the impact of interventions aimed at reducing risk factors in high-risk groups. Moreover, investigating genetic and environmental interactions contributing to CVD risk in diverse populations could provide valuable insights.

By addressing these limitations and expanding research efforts in this area, including replication studies in different regional and demographic contexts, the findings of our study could pave the way for a more comprehensive understanding of modifiable CVD risk factors and their implications for public health strategies.

While our study provides valuable insights into the latent structure of modifiable CVD risk factors, it does not directly assess the predictive ability of these risk factors in forecasting CVD outcomes. The primary focus of this study was on identifying distinct latent classes of risk factors rather than developing predictive models. As such, the applicability of the identified latent classes for direct prediction of CVD events remains an area for future research.

Additionally, the use of Latent Class Analysis (LCA) inherently focuses on subgroup identification based on observed data patterns rather than predicting outcomes. The lack of a labeled outcome variable in our dataset, such as CVD diagnosis or progression, limits the ability to employ supervised machine learning methods to evaluate predictive utility.

Future studies could address this limitation by incorporating longitudinal data or labeled outcomes, enabling the use of machine learning or deep learning models to validate the predictive utility of the identified latent classes. This would provide a deeper understanding of how these latent structures correlate with CVD risk over time and their potential use in clinical risk prediction.

Implications for practice

These findings enhance our understanding of modifiable CVD risk factors by showing the interaction between different risks and identifying distinct patterns of risk factors using Latent Class Analysis (LCA). This method allowed us to classify individuals into subgroups with unique combinations of modifiable risks, offering valuable insights into how these risks co-occur within a population.

In clinical practice, these insights can inform the development of targeted interventions tailored to specific risk profiles, thereby optimizing resource allocation and improving health outcomes. For example, individuals in high-risk classes could benefit from comprehensive lifestyle modification programs, while those in lower-risk classes might require less intensive interventions. Additionally, understanding these patterns can aid in designing health protocols that address the unique needs of different demographic groups, particularly in settings with similar rural and demographic characteristics to the Kherameh cohort.

While LCA has provided robust insights, we acknowledge that future studies could explore complementary methods to further validate these findings and investigate how they apply to other populations and settings.

Policy recommendations

Based on our findings, several policy recommendations can be made to address CVD risk factors in similar populations. Public health interventions should focus on:

Targeting Key Risk Factors: Prioritize interventions addressing abdominal obesity and smoking, which are prominent risk factors in our identified groups. This approach can streamline efforts and enhance the effectiveness of health initiatives.

Increasing Awareness: Develop tailored awareness campaigns that stress the importance of regular health check-ups, with an emphasis on managing weight and quitting smoking, particularly targeting rural and older populations.

Implementing Targeted Educational Campaigns: Focus educational efforts on reducing smoking and alcohol consumption, with special attention to how these behaviors interact with other risk factors like obesity.

Enhancing Access to Healthcare: Improve healthcare access in rural areas to detect and manage clinical risk factors early, ensuring services are equipped to address issues like obesity and smoking cessation.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [HGH], upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- LCA:

-

Latent class analysis

- NCD:

-

Non-communicable diseases

- YLL:

-

Years of life lost

- DALY:

-

Disability-adjusted life years

- IHD:

-

Ischemic heart disease

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- PERSIAN:

-

Prospective Epidemiological Research Studies in Iran

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- BIC:

-

Bayesian information criterion

- AIC:

-

Akaike information criterion

References

Joseph, P. et al. Reducing the global burden of cardiovascular disease, part 1: the epidemiology and risk factors. Circ. Res. 121, 677–694 (2017).

Sarrafzadegan, N. & Mohammmadifard, N. Cardiovascular disease in Iran in the last 40 years: Prevalence, mortality, morbidity, challenges and strategies for cardiovascular prevention. Arch. Iran. Med. 22, 204–210 (2019).

Ghaemian, A., Nabati, M., Saeedi, M., Kheradmand, M. & Moosazadeh, M. Prevalence of self-reported coronary heart disease and its associated risk factors in Tabari cohort population. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 20, 1–10 (2020).

Baeradeh, N. et al. The prevalence and predictors of cardiovascular diseases in Kherameh cohort study: A population-based study on 10,663 people in southern Iran. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 22, 244 (2022).

World Health, O. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. (World Health Organization, 2011).

Sarraf-Zadegan, N. et al. Secular trends in cardiovascular mortality in Iran, with special reference to Isfahan. Acta Cardiol. 54, 327–333 (1999).

Hippisley-Cox, J. et al. Predicting cardiovascular risk in England and Wales: prospective derivation and validation of QRISK2. BMJ 336, 1475–1482 (2008).

Yusuf, S. et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. The Lancet 364, 937–952 (2004).

Huxley, R., Mendis, S., Zheleznyakov, E., Reddy, S. & Chan, J. Body mass index, waist circumference and waist: Hip ratio as predictors of cardiovascular risk—a review of the literature. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 64, 16–22 (2010).

Steptoe, A. & Kivimäki, M. Stress and cardiovascular disease: An update on current knowledge. Annu. Rev. Public Health 34, 337–354 (2013).

Timmis, A. et al. European society of cardiology: Cardiovascular disease statistics 2019. Eur. Heart J. 41, 12–85 (2020).

Poustchi, H. et al. Prospective epidemiological research studies in Iran (the PERSIAN Cohort Study): Rationale, objectives, and design. Am. J. Epidemiol. 187, 647–655 (2018).

Conroy, R. M. et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: The SCORE project. Eur. Heart J. 24, 987–1003 (2003).

D’Agostino, R. B. Sr. et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 117, 743–753 (2008).

Saugel, B., Dueck, R. & Wagner, J. Y. Measurement of blood pressure. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 28, 309–322 (2014).

Ghosh, A., Halder, D. & Mukhopadhyay, K. Comparative assessment of blood pressure, random blood sugar and addiction status among security staffs and scavengers in an Indian medical college hospital. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci 5, 294–300 (2016).

Tayefi, M. et al. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure percentiles by age and gender in Northeastern Iran. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 12, e85–e91 (2018).

Roth, G. A. et al. High total serum cholesterol, medication coverage and therapeutic control: an analysis of national health examination survey data from eight countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 89, 92–101 (2011).

McGee, S. Evidence-based physical diagnosis e-book (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2021).

Cappuccio, F. P., Cooper, D., D’Elia, L., Strazzullo, P. & Miller, M. A. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. Heart J. 32, 1484–1492 (2011).

Min, Y. & Slattum, P. W. Poor sleep and risk of falls in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. J. Appl. Gerontol. 37, 1059–1084 (2018).

Aflaki, K., Vigod, S. & Ray, J. G. Part I: A friendly introduction to latent class analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 147, 168–170 (2022).

Hagenaars, J. A. & McCutcheon, A. L. Applied latent class analysis (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

Clark, S. L. & Muthén, B. (Los Angeles, California, USA, 2009).

Bu, F., Steptoe, A. & Fancourt, D. Relationship between loneliness, social isolation and modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease: A latent class analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health 75, 749–754 (2021).

Weycker, D. et al. Risk-factor clustering and cardiovascular disease risk in hypertensive patients. Am. J. Hypertens. 20, 599–607 (2007).

Poortinga, W. The prevalence and clustering of four major lifestyle risk factors in an English adult population. Prev. Med. 44, 124–128 (2007).

Wei, X. et al. Characteristics of high risk people with cardiovascular disease in Chinese rural areas: Clinical indictors, disease patterns and drug treatment. PLoS ONE 8, e54169 (2013).

Rodgers, J. L. et al. Cardiovascular risks associated with gender and aging. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd6020019 (2019).

Choinière, R., Lafontaine, P. & Edwards, A. C. Distribution of cardiovascular disease risk factors by socioeconomic status among Canadian adults. CMAJ 162, S13–S24 (2000).

Yu, Z. et al. Associations between socioeconomic status and cardiovascular risk factors in an urban population in China. Bull. World Health Organ. 78, 1296–1305 (2000).

Cho, C.-M. & Lee, Y.-M. The relationship between cardiovascular disease risk factors and gender. Health 4, 309–315 (2012).

Gu, D. et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factor clustering among the adult population of China: Results from the international collaborative study of cardiovascular disease in Asia (InterAsia). Circulation 112, 658–665 (2005).

Costache, I. I. et al. Associations between area of residence and cardiovascular risk. Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala 49, 68 (2015).

Tareen, M. F. et al. Location of residence or social class, which is the stronger determinant associated with cardiovascular risk factors among Pakistani population? A cross sectional study. Rural Remote Health 11, 32–39 (2011).

Joshi, R., Taksande, B., Kalantri, S. P., Jajoo, U. N. & Gupta, R. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among rural population of elderly in Wardha district. J. Cardiovasc. Dis. Res. 4, 140–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcdr.2013.03.002 (2013).

Turecamo, S. E. et al. Association of rurality with risk of heart failure. JAMA Cardiol. 8, 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2022.5211 (2023).

Babahajiani, M. et al. Ethnic differences in the lifestyle behaviors and premature coronary artery disease: A multi-center study. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 23, 170. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-023-03192-0 (2023).

Ghorashi, S. M. et al. Association between nontraditional risk factors and calculated 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in a large general population: Based on the pars cohort study. J. Tehran Univ. Heart Center 18, 24 (2023).

Winkleby, M. A., Jatulis, D. E., Frank, E. & Fortmann, S. P. Socioeconomic status and health: how education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Public Health 82, 816–820 (1992).

Zhang, Y.-B. et al. Associations of healthy lifestyle and scioeconomic status with mortality and incident cardiovascular disease: Two prospective cohort studies. BMJ 373, n604 (2021).

Alviar, C. L., Rockman, C., Guo, Y., Adelman, M. & Berger, J. Association of marital status with vascular disease in different arterial territories: A population based study of over 3.5 million subjects. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 63, A1328–A1328 (2014).

Chen, R. et al. Marital status, telomere length and cardiovascular disease risk in a Swedish prospective cohort. Heart 106, 267–272 (2020).

Dumith, S. C., Muniz, L. C., Tassitano, R. M., Hallal, P. C. & Menezes, A. M. B. Clustering of risk factors for chronic diseases among adolescents from Southern Brazil. Prev. Med. 54, 393–396 (2012).

Schuit, A. J., van Loon, A. J. M., Tijhuis, M. & Ocké, M. C. Clustering of lifestyle risk factors in a general adult population. Prev. Med. 35, 219–224 (2002).

Berlin, K. S., Williams, N. A. & Parra, G. R. An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): Overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 39, 174–187 (2014).

Weller, B. E., Bowen, N. K. & Faubert, S. J. Latent class analysis: A guide to best practice. J. Black Psychol. 46, 287–311 (2020).

Vermunt, J. K. & Magidson, J. Latent class analysis. Sage Encycl. Soc. Sci. Res. Methods 2, 549–553 (2004).

Miettunen, J., Nordström, T., Kaakinen, M. & Ahmed, A. O. Latent variable mixture modeling in psychiatric research–A review and application. Psychol. Med. 46, 457–467 (2016).

Tegegne, T. K., Islam, S. M. S. & Maddison, R. Effects of lifestyle risk behaviour clustering on cardiovascular disease among UK adults: Latent class analysis with distal outcomes. Sci. Rep. 12, 17349 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This article was a part of Hadis Salimi’s MSc thesis, approved and financially supported by the Research Vice-chancellor of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Grant no. 1402-4-4-28337). The Ethics Committee approved this study at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (IR.SUMS.SCHEANUT.REC.1402.052). This paper was edited using large language models (LLMs), including Bard and ChatGPT. However, the accuracy of all information was independently verified by the authors.

Funding

This article was a part of Hadis Salimi’s MSc thesis, approved and financially supported by the Research Vice-chancellor of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Grant no. 1402-4-4-28337).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.G. is the lead author and guarantor and contributed to interpreting the data and revising the manuscript. H.S. and M.V. planned the study and led the drafting and revising of the manuscript. H.S., M.V., A.R., M.Gh. and H.G. contributed to interpreting the data and drafting and revising the manuscript. All authors approved the submitted version of the manuscript. All authors have contributed to the preparation of the manuscript, have read, and approved the submitted manuscript. All authors listed meet the authorship criteria according to the latest guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors and agree with the manuscript. The work is original and not under consideration by any other journal.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

PERSIAN Cohort Study is being performed in 18 geographical regions of Iran. PERSIAN Cohort Study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health and Medical Education. This study was in agreement with the Helsinki Declaration and Iranian national guidelines for ethics in research (IR.SUMS.SCHEANUT.REC.1402.052). Besides, Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Salimi, H., Vali, M., Rezaianzadeh, A. et al. Patterns of risk factors for cardiovascular diseases in Kheramah PERSION cohort population using a latent class analysis. Sci Rep 15, 24496 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08334-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08334-2