Abstract

This paper addresses the problem of detecting money laundering in the Bitcoin network. Money laundering is the process of handling the proceeds of crime to conceal their illegal source, these illicit transactions have complex features, similar to those of legal transactions. It is well known that transactions can be represented as topological graph structure data, and many GCN-based methods have been developed for Anti-Money Laundering (AML) tasks. However, existing methods have not performed as well in dynamically assigning weights to neighboring nodes and extracting information from global nodes in the Bitcoin network. Therefore, we identify three major challenges: Firstly, GCNs can be misled by concealed illegal transactions due to uniform node representation weights. Secondly, current node-level GCNs cannot handle varied methods of concealing illegal transactions because they fail to extract global information. Thirdly, the costliness of data labelling necessitates the effective use of limited but rich domain-specific labelled data. To address these challenges, we propose the Transformer-enhanced Graph Attention Network (TFGAT) with a Global-Local Attention Mechanism (GLATM) that uses Transformers to extract global information and selectively focus on local information from connected nodes. Due to the limited availability of labelled data from expensive data labelling processes, we introduce a Deep Cyclic Pseudo-Label Updating Mechanism (DCPLU) to enhance data distribution and model robustness, which does not rely on manifold structure or Euclidean distance assumptions. DCPLU can enhance model performance while preserving the model’s existing parameters, enabling it to maintain its current faster response time in the application scenario. Experimental results show that our methods outperform existing models across various metrics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent years, money laundering has become one of the major threats to national public security (Labib et al.1). This process involves concealing the illicit origins of criminal proceeds, enabling offenders to enjoy their gains without revealing the source (Force et al.2). The amount of money susceptible to laundering is estimated to range between 2% and 5% of the global Gross Domestic Product (GDP). However, a significant portion of this sum is difficult to trace and never enters the banking system (Dumitrescu et al.3). Therefore, cryptocurrency has become one of the favoured tools for money laundering, criminals employ various techniques to obfuscate the source of funds (Fletcher et al.4). In the area of Bitcoin, Bitcoin mixes, Bitcoin exchanges and the use of both methods are common methods of money laundering (Beessoo et al.5), as depicted in Fig. 1. Moreover, the above methods have many different types (Ziegeldorf et al.6). This complexity renders money laundering transactions akin to legal ones, deliberately concealed and possessing intricate features. The Anti-Money Laundering (AML) system is deployed by financial institutions including banks and other credit-providing entities. As a result, anti-money laundering (AML) laws have begun to focus on combating the laundering of Bitcoin as an important branch. (Guo et al.7).

Anti-Money Laundering (AML) tasks constitute a systematic framework for identifying potential illicit financial activities through the integration of multi-source data. This encompasses client profiling data (including identity verification and transactional histories), external risk indicators (such as sanctions lists and politically exposed person databases), alongside predefined detection rules and machine learning models. The analytical process focuses on detecting anomalous transactional patterns, high-risk client associations, and behavioural deviations that may indicate money laundering or terrorist financing activities8,9.

The Bitcoin transaction system is a rare example of a large-scale global payment system in which all transactions are publicly accessible (though anonymously) (Ron et al.10). This means that anyone can view the transaction records on the blockchain, enabling them to construct topological graphs to analyse the flow of Bitcoin. Therefore, our research primarily focuses on graph-based approaches. Based on the raw Bitcoin data, a graph can be constructed and labelled where nodes represent transactions and edges represent the flow of Bitcoin currency (BTC) from one transaction to the next (Weber et al.11). The flow of Bitcoin is expressed using a topological graph, making tracking and capture more efficient.

Many models based on Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) have recently achieved significant success in AML tasks. Weber et al.11 designed the Elliptic dataset and conducted experiments using various machine learning models, including GCN and Skip-GCN. This research serves as a crucial baseline study. Mohan et al.12 presented an innovative approach that combines the strengths of random forest with dynamic graph learning methods. Alarab et al.13 underscored the significance of incorporating temporal correlation into models and contracted classification models involving Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and GCN. Yang et al.14 introduced an integrated model combining LSTM and GCN, employing a hard voting mechanism to enhance the detection of laundering techniques by synergising multiple anomaly detection classifiers such as Histogram-Based Outlier Scoring (HBOS) and Isolation Forest (Karim et al.15).

However, most existing GCN-based methods face three major challenges:

-

Firstly, in industry, illegal transactions are concealed within legal transaction chains, forming an interleaved transaction graph with millions of isolated user groups, which intensifies the presence of noise in the data (Force et al.2, Li et al.16). This characteristic degrades the embedding quality of GCN-based methods, which assign the same weight to all neighbouring nodes; they prefer data formats that are more regular and less noisy (Zhou et al17).

-

Secondly, extracting global information helps capture the varied methods of money laundering (Jensen et al.18). In addition, most existing GCN-based models primarily focus on extracting local information within static graphs (Yun et al.19), which is infeasible to extract global information.

-

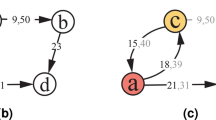

Thirdly, conventional money laundering data labelling often requires professionals to screen the data. Labelled data incorporates insights from diverse professional domains, rendering data labelling prohibitively expensive within authentic financial institutions (Luo et al.20, Karim et al.15, Lorenz et al.21, Lo et al.22). Therefore, most data remains unlabeled, presenting a dual challenge: harnessing the specialised knowledge embedded in labelled data while mitigating the scarcity of labels. However, traditional label propagation assumes that similar samples in the feature space should have the same label as shown in Fig. 2, invalid in the AML task.

To deal with these challenges, in this paper, we propose the Transformer-enhanced Graph Attention Network (TFGAT) for money laundering detection in Bitcoin networks. Unlike other GCN-based methods, our proposed model can extract global information from various money laundering methods embedded in nodes and dynamically assign weights. Specifically, we first mine global information from the entire graph and embed it into graph nodes by Transformer. Then we utilize GAT’s graph attention mechanism to dynamically assign node weights (i.e., the features of the graph nodes contain global information). Due to the scarcity of labelled data resulting from expensive labelling processes, we introduce a Deep Cyclic Pseudo-Label Updating Mechanism (DCPLU) to augment data distribution and fortify the model’s robustness. Concretely, we train a supervised TFGAT model to generate pseudo labels for unlabeled data. A semi-supervised TFGAT model is then trained using the entire graph (i.e., including original labels and pseudo-labels) to update the pseudo-labels, cycling until the training effect converges. The flowchart of our method is shown in Fig. 3. The main contributions are summarized as follows:

-

We propose the TFGAT model for money laundering detection in Bitcoin networks, which aims to uncover illegal transactions concealed by various money laundering methods. This is the first attempt to introduce a Global-Local Attention Mechanism (GLATM) involving a Transformer to extract global transaction information to enrich the GAT’s dynamic local money laundering information transmission.

-

We propose a Deep Cyclic Pseudo-Label Updating Mechanism (DCPLU) for addressing anti-money laundering issues with limited labelled data. In addition, we mine pseudo-labels and update them for unlabeled transactions using a TFGAT model to better utilize both unlabeled data and expert knowledge-rich labelled data. DCPLU optimises the data distribution of the pseudo-label enriched training set, improves model performance, and keeps the model parameters unchanged, allowing the model to maintain its existing faster response time in the application scenario.

-

This is the first time that the use of feature-level global attention to improve the performance of the GAT model has been proposed for the anti-money laundering task. The GAT model typically focuses on the interactions between nodes and often neglects feature extraction, as shown in Fig. 4. In the context of the anti-money laundering task, each feature holds significant practical importance. If feature extraction is overlooked, a substantial amount of valuable information may be lost.

-

We extensively experiment and conduct ablation studies to evaluate the proposed approach, comparing it with the existing baseline on the Elliptic dataset, and achieving state-of-the-art performance.

We organize the remainder of the paper as follows. “Related work” presents the related work. “Method” describes our proposed method in detail. The experimental results are presented in “Experiment”. Finally, the main conclusions are discussed in “Conclusion”.

Related work

In financial institutions, traditional anti-money laundering practices rely heavily on legal and regulatory frameworks (Zagaris et al.23). However, as money laundering techniques evolve, machine learning has emerged as a powerful tool in combating financial crime (Yousse et al.9). Many machine learning approaches have been designed to identify money laundering activities effectively, including GCN-based deep learning methods (Han et al.8). In this section, we mainly overview the literature about GCN-based methods in the AML area, and we conclude the summary of different approaches at the end of this section. We categorise the major solutions into two branches:

-

(1) The GCN-based supervised methods.

-

(2) The GCN-based semi-supervised methods.

The GCN-based supervised methods

Weber et al.24 constructed the AMLSim dataset and used GCN and FastGCN for training and prediction. Weber et al.11 constructed the Elliptic dataset for training and prediction using different machine-learning methods. The experimental results showed that GCN performed impressively. Huang et al.25 presented the TemporalGAT model, which utilises temporal and spatial attention mechanisms to improve AML task performance. Wei et al.26 introduced a Dynamic Graph Attention Network (DynGAT), that captures the dynamics of the graph sequence through a multi-head self-attention block on the sequence of concatenations of node embeddings and time embeddings. Ouyang et al.27 proposed a novel subgraph-based contrastive learning algorithm for heterogeneous graphs, named Bit-CHetG, that employs supervised contrastive learning to reduce the effect of noise, which pulls together the transaction subgraphs with the same class while pushing apart the subgraphs with different classes.

Existing supervised GCN-based methods in AML have made significant progress in AML tasks. However, their robustness is insufficient due to the sparse distribution of effectively labelled transactions. Therefore, GCN-based semi-supervised methods are attracting the interest of the AML industry as they can improve the distribution of labels and strengthen the robustness of the model.

The GCN-based semi-supervised methods

Wang et al.28 constructed an integrated model based on GCN and LPA for node classification. Bellei et al.29 showed that a modification of the first layer of a GCN can be used to propagate label information across neighbour nodes effectively. Ghayekhloo et al.30 introduced CLP-GCN to propagate the confidence scores of the labels and assign pseudo-labels to nodes. Zhang et al.31 utilised the GCN and unified the LPA to provide regularisation of training edge weights in recommendation tasks. Xie et al.32 designed a Label Efficient Regularization and Propagation (LERP) framework for graph node classification and introduced an optimization procedure to replace GraphHop. Tan et al.33 showed a LE algorithm based on GCN, called LE-GCN, which extends GCN to the LE field based on the smoothness assumption of the manifold to fully exploit the hidden relationships between nodes and labels.

Traditional label propagation typically involves the following three model assumptions:

-

Label similarity assumption If two samples have the same or similar labels, then their Euclidean distance in feature space should be small.

-

Smoothness assumption If two samples are adjacent in the feature space, then their labels should also be similar, which is very practical for the manifold structure.

-

Consistency assumption The label of a sample is greatly affected by the labels of samples in its local neighbourhood. Label propagation mainly takes place in the local neighbourhood. This idea is also applied to the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm.

However, these assumptions are invalid for AML tasks because illegal transactions can be influenced by human factors and hidden among legal transactions. This is why we use the Deep Cyclic Pseudo-Label Updating Mechanism (DCPLU).

Xiang et al.34 designed a Gated Temporal Attention Network (GTAN), a semi-supervised method that passes messages among the nodes in a temporal transaction graph. Karim et al.15 presented a semi-supervised graph learning approach in pipeline and end-to-end settings to identify nodes involved in potential money laundering transactions. Luo et al.20 constructed a transaction relationship network based on node similarity (TRNNS) for semi-supervised decoupling training. Li et al.16 introduced the innovative Diga model, the first Graph-based semi-supervised method to apply the diffusion probabilistic model in AML tasks. Navarro et al.35 constructed an easy way to fuse information from model performance and cost risks to establish the corresponding threshold for the output model to distinguish between licit and illicit transactions. Tang et al.36 designed the pretext task for the node embedding module so that their model can learn the appropriate node embedding by using a large amount of unlabeled node data. Zhang et al.37 constructed a dynamic embedding method, DynGraphTrans, which leverages the powerful modelling capability of a universal transformer for temporal evolutionary patterns of financial transaction graphs.

However, existing node-level models are ineffective in capturing the complexities of real-world money laundering methods, as unconnected nodes may contain valuable information (Yun et al.19). Moreover, money laundering activities concealed within legal transactions are difficult to identify using a single weight in GCN. Our work exploits a global-local attention mechanism and a Deep Cyclic Pseudo-Label Updating Mechanism (DCPLU) to detect more money laundering patterns and make the model more robust, significantly improving performance in AML tasks.

Method

In this section, we will introduce the transaction graph, the global-local attention mechanisms and the Deep Cyclic Pseudo-Label Updating Mechanism (DCPLU).

The graph-structured data of the transaction is an isomorphic graph of the Bitcoin transaction network based on the Elliptic dataset. The goal of the global-local attention mechanisms is to extract global transaction information to embed node features and dynamically select local information about the neighbouring transaction. In contrast to most GCN-based methods for graphs with only local information, TFGAT searches the entire transaction graph using a Transformer to extract global information. At the same time, the dynamic selection of local information is more useful for connected metapaths, i.e. paths that are connected with isomorphic edges. The Deep Cyclic Pseudo-Label Updating Mechanism (DCPLU) aims to assign pseudo-labels to unlabelled data while iteratively refining these estimations during semi-supervised training, thereby guiding the model towards convergence through an early stopping-determined termination criterion.

The transaction graph

The transaction graph \(G=(U, R)\) consists of the set of transactions \(U=\{u_i \mid i=1,2,...,n\}\) as the nodes and the flow of BTC R as the edges. The node attribute matrix \(X = X_{l} \cup X_{\tilde{l}}\) represents the features of the transactions U, including the basic information and the aggregated features. Here, \(X_{l}\) stands for the features of the labelled transactions and \(X_{\tilde{l}}\) for the features of the unlabelled transactions. The binary label y is defined by the experts of the Elliptic Cryptocurrency Intelligence Company and indicates whether the labelled transactions are suspicious of money laundering or not.

The supervised TFGAT with global-local attention mechanisms (GLATM)

First, the supervised TFGAT is trained for the pseudo-labelling process to improve performance through global-local attention mechanisms in AML tasks. The TransformerEncoder uses a self-attention mechanism with three weight matrices: Query (Q), Key (K) and Value (V). By comparing Q and K, a score (indicating correlation or similarity) is calculated. This score is then multiplied by the corresponding V to obtain the final result. The linear mappings for Q, K, and V are represented by the weight matrices \({W}_{Q}\), \({W}_{K}\), and \({W}_{V}\), respectively, where \({W}_{Q}\), \({W}_{K}\), and \({W}_{V}\) denote the weights for the Q, K, and V components.

The three weight matrices here are all square, which means that the dimensions of Q, K and V are the same as those of X. Essentially, ”multi-head” is about partitioning the matrix from the dimension of X into several segments, each of which represents a head. The dimensions after the partitioning of Q, K and V are referred to as M:

Here, \({M}_{X}\) stands for the dimensionality of X, and \({M}_{H}\) for the number of heads. Then Q, K and V represent the linear mapping results of the one head and utilise the idea that a larger dot product of two vectors implies a larger similarity, and then obtain the attention matrix by \(QK^T\). Based on the attention matrix, weighted values are then calculated, which are expressed as follows:

Here, the symbol \({\sqrt{d_k}}\) stands for a normalization operation that aims to transform the attention matrix into a standard normal distribution. This operation ensures that the embedding of information for each transaction contains the information from all transactions in the entire graph structure. Subsequently, the final output of the multi-head attention mechanism is achieved by applying the operation Add & Norm, the operation Feedforward and another operation Add & Norm:

Here \(\omega\) stands for the weight of the linear layer and Relu is the activation function.

Then A shared weight matrix \(W \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times m}\) is trained for all nodes to obtain weights for each neighbouring node. This weight matrix represents the relationship between the n input features and m output features, serving as a mapping. When computing attention values, the features of nodes \({X'}_{Attention}^{(u)}\) and \({X'}_{Attention}^{(v)}\) are separately mapped using W, and the resulting vectors are concatenated (note that due to the concatenation operation, the attention values between nodes are asymmetric). Subsequently, a feedforward neural network \(\tilde{\bf{a}}^T\) is exercised to map the concatenated vector to a real number, followed by LeakyReLU activation. After softmax normalization, the final attention coefficients are obtained. The || symbol denotes vector concatenation:

Here, \({X}_{Attention}^{(u)}\) denotes the features of the u-th node after feature extraction by TransformerEncoder (analogous for \({X}_{Attention}^{(v)}\)). \(e_{uv}\) stands for the attention values obtained, and \(\alpha _{uv}\) denotes the attention coefficients. After obtaining the attention coefficients, a weighted sum over the neighbours is formed to derive the output features for the node u:

The multi-head attention mechanism is introduced to increase the representational capacity of the model and stabilize the self-attention for node representation. In the intermediate layer, the self-attention is calculated using k different weight matrices W, and the results of the attention heads are combined into an output vector. For the final result, an averaging strategy is applied to the output vectors of the different attention heads:

Next, the deep neural network layer maps the attentional information onto a two-dimensional probability distribution and then classifies it through the softmax layer:

Here, \(\omega\) denotes the weights of the linear layer, and ReLU serves as the activation function. The output \(\hat{y} = \hat{y}_{l} \cup \hat{y}_{\tilde{l}}\) comprises two components: predictions for labelled transactions \(\hat{y}_{l}\) and pseudo-labels for unlabelled transactions \(\hat{y}_{\tilde{l}}\), where the union operator \(\cup\) indicates the combined set of supervised predictions and unsupervised estimations. The supervised TFGAT training only considers labelled transaction nodes when calculating the loss function. At the same time, the weighted cross-entropy loss function can address the underfitting of minority class samples caused by data imbalance, enabling the model to focus more on illegal transactions:

Here, L is the number of labelled transactions. \(w_{legal}\) and \(w_{illegal}\) denote the weight assigned to the categories of legal and illegal transactions, respectively, for the i-th labelled transaction.

The semi-supervised TFGAT With deep cyclic pseudo-label updating mechanism (DCPLU)

Besides the different data distribution between Bitcoin transactions and others (e.g., natural language and image domain), the technical challenge of the pseudo-labelling process in such an unexplored domain is how to distinguish the error in concealed transactions, which has a nonlinear complex structure that cannot be solved by Euclidean distance. Therefore, we develop the semi-supervised TFGAT with a Deep Cyclic Pseudo-Label Updating Mechanism (DCPLU):

-

Through the supervised TFGAT get pseudo-labels \(\hat{y}_{\tilde{l}}\) on each unlabeled transaction node.

-

Then, cyclic semi-supervised training aims to continuously update pseudo-labels for each unlabeled node until the model’s performance converges.

First, \(y_{new}\) is the new label, which is the combination of the pseudo-label \(\hat{y}_{\tilde{l}}\) and the original true label y. During subsequent training, the training process from the “The supervised TFGAT with global-local attention mechanisms (GLATM)”:

Here,\(\hat{y}_{\sigma } =\hat{y}_{{\sigma }_{l}} \cup \hat{y}_{{\sigma }_{\tilde{l}}}\), \(\hat{y}_{\sigma }\) includes the prediction of the labeled transactions \(\hat{y}_{{\sigma }_{l}}\) and the new pseudo-labels of the unlabeled transactions \(\hat{y}_{{\sigma }_{\tilde{l}}}\). It is worth noting that the loss function will change at this point:

Next, the new pseudo-labels \(\hat{y}_{{\sigma }_{\tilde{l}}}\) are combined with the original true labels y to form a new label set \(y_{new}^*\), and another round of semi-supervised training is performed with the updated labels \(y_{new}^*\). In this iterative process, the pseudo-labels are refined until the model converges to the validation set. Specific details on the training iterations can be found in Algorithm 1.

Finally, the converged model \(TFGAT_{\Delta }\) and the final prediction result \(\hat{y}_\Delta\) can be obtained by the Deep Cyclic Pseudo-Label Updating Mechanism (DCPLU).

Experiment

This section evaluates the TFGAT model, which has been optimised using the Deep Cyclic Pseudo-Label Updating Mechanism (DCPLU) mechanism. The experimental results show that our proposed DCPLU effectively captures money laundering transactions hidden within legitimate transactions. These transactions typically exhibit non-manifold structures and extremely unbalanced label distributions, rendering Euclidean distance-based methods ineffective. DCPLU can effectively extract information from these structures without relying on model assumptions outlined in Section 4.1, which are inherent in traditional methods. To conclude, we conducted an ablation study to evaluate the effectiveness of each component of the model.

Datasets

The Elliptic dataset was constructed by Weber et al.11, which is a topological graph dataset with temporal correlations. It comprises over 200,000 Bitcoin transaction nodes, 234,000 transaction edges and 49 different timestamps. Each timestamp is about 2 weeks apart, and each transaction node is labelled as ”licit”, ”illicit” or ”unknown”.

Concealed illegal transaction: Based on our observations, we find that illegal transactions and legal transactions in the Bitcoin network have surprisingly similar features, making the entire dataset non-manifold and non-linearly separable. This and the extremely unbalanced data distribution make the modelling assumptions of traditional label propagation completely invalid. Figure 5 presents the results of five dimensionality reduction methods.

From Figure 5, it is clear that transaction nodes with different labels are closely intertwined. At the same time, the transaction data does not exhibit a manifold structure or a linearly separable state, invalidating traditional label propagation assumptions, as shown in Table 2. Therefore, we propose the TFGAT model, which can recognise the self-concealment of money laundering transactions.

Settings

In the experimental settings, we build a TFGAT model based on a Deep Cyclic Pseudo-Label Updating Mechanism (DCPLU) to detect money laundering based on the graph structure of Bitcoin transactions. Through rigorous Bayesian hyperparameter optimisation, we systematically determined the optimal architectural configuration: 2 TransformerEncoder layers with 4 parallel attention heads per layer, employing 512-dimensional representations (d-model) for latent transaction pattern encoding. This parameter selection – refined from candidate ranges of 1 4 encoder layers, 2 8 attention heads, and d-model dimensions \(\{192, 256, 512, 1024\}\). The finalised architecture maintained these optimised parameters throughout both initial supervised training and subsequent pseudo-label refinement phases of our dual-stage learning protocol.

-

The supervised TFGAT training We employ the weighted cross-entropy loss function with alpha (legal transactions) set to 1.0. The beta parameter (illegal category) is obtained through rigorous Bayesian hyperparameter optimisation, with a parameter search range of 2 to 15, ultimately determined to be 10. The model demonstrating the highest F1-score on the validation set is selected as the final implementation. For training configuration, we implement 1000 epochs using the Adam optimiser, while the \(L_2\) loss weight is derived through rigorous Bayesian hyperparameter optimisation across a parameter search range of \(1e^{-4}\) to \(1e^{-6}\), ultimately set to \(5e^{-5}\). The learning rate undergoes a 20% reduction every 100 training iterations.

-

The deep cyclic pseudo-label updating mechanism We employ the weighted cross-entropy loss function with alpha (legal transactions) set to 1.0. The beta parameter (illegal category) is obtained through rigorous Bayesian hyperparameter optimisation, with a parameter search range of 2 to 15, ultimately determined to be 6. The model demonstrating the highest F1-score on the validation set is selected as the final implementation. For training configuration, we implement 1000 epochs using the Adam optimiser, while the \(L_2\) loss weight is derived through rigorous Bayesian hyperparameter optimisation across a parameter search range of \(1e^{-4}\) to \(1e^{-6}\), ultimately set to \(5e^{-5}\). The learning rate undergoes a 10% reduction every 100 training iterations.

Parameter sensitivity analysis

A systematic Bayesian hyperparameter optimisation process reveals the robustness of our TFGAT-DCPLU framework.

Shallow 2-layer encoder configurations (selected from 1-4 candidates) show remarkable resilience; deeper architectures yield diminishing returns (+0.8% F1 gain per additional layer) while exponentially increasing computational complexity. This suggests that our model can effectively capture key transaction patterns without over-engineering. A 512-dimensional latent space (selected from 192, 256, 512, 1024) appears to strike an optimal balance, providing sufficient representational capacity while avoiding overfitting, as evidenced by a less than 2% difference in F1 scores between training and validation sets.

Notably, the framework maintains consistent performance despite significant differences in class weight parameters. beta=10 (illegal class weight) in the supervised stage and beta=6 in the semi-supervised stage demonstrate the adaptability of our model to different learning mechanisms, and the precision-recall curve remains stable (F1 score variance \({\pm }2\)%) in the search range of 2-15 beta. The \(L_2\) regularisation (\(5e^{-5}\)) shared by both training stages further demonstrates its inherent structural stability.

Our model maintains detection efficacy under different parameter configuration scenarios–a key advantage in real-world financial anomaly detection systems where trading patterns evolve dynamically.

Evaluation metrics

For the sake of fairness, we leveraged the experimental results from Weber et al.11, Vassallo et al.38 and Lo et al.22, using the same metrics to evaluate our model. This included precision, recall, and F1-score for the ”Illicit” class.

The \(TP_{illegal}\) (true positive for illicit transactions) denotes the correct identification of unlawful transactions as ”illegal”, while \(FP_{illegal}\) (false positive for illicit transactions) refers to the erroneous classification of legitimate transactions as ”illegal”. Conversely, \(FN_{illegal}\) (false negative for illicit transactions) represents the misclassification of unlawful transactions as ”legal”. These specifically tailored metrics for illicit financial activities offer granular analytical capabilities, thereby enabling targeted refinement of detection models when applied to anti-money laundering case samples.

TFGAT with traditional label propagation

We designed a semi-supervised training experiment for TFGAT using the traditional label propagation method and compared it with our proposed TFGAT via DCPLU. Furthermore, the experiment includes four label propagation methods: Label Propagation Algorithm (LPA), Heat Kernel Label Propagation (HKLP), Normalized Label Propagation (NLP) and Personalized PageRank Label Propagation (PPLP). The results are shown in Table 2, which illustrates that traditional label propagation methods prove ineffective in AML tasks, while our proposed method demonstrates significant superiority across various metrics.

Ablation study

The proposed method contains some key components, and we verify their effectiveness by ablating each component. Our ablation study is based on the Elliptic dataset. The influencing factors of our method include the Transformer layer, the GAT layer and the deep cyclic pseudo-label updating mechanism. The results are shown in Table 3. From Table 3, it is clear that the loss of any of these factors leads to performance degradation, with the performance degradation being most severe when no Transformer layer is present. With the same number of parameters (about 6.7M), the training time of TFGAT is between the standard GAT implementation (3.2 hours) and the pure Transformer architecture (4.7 hours). It is worth noting that although the training cycle incurs an additional 25% time overhead (from 4.1 hours to 5.1 hours) after adding DCPLU integration, it can improve the recognition performance of illegal transactions and maintain the original number of parameters of the model, which can keep the original faster response speed of the model in actual application scenarios.

Performance

We selected 21 representative baseline methods, including classic models, current best-performing models, and domain-specific methods related to this study. These include the graph convolutional network (GCN) used in the study of Weber et al.11 and its variant Skip-GCN, as well as EvolveGCN combined with temporal modelling and its baseline models: logistic regression, random forest, and multi-layer perceptron (MLP), XGBoost used in the study of Vassallo et al.38, GraphSAGE used in the study of arasi et al.39 and the Inspection-L model used in the study of Lo et al.22 AF refers to the use of all features (all 166 features), LF refers to the use of local features (the first 94 features), NE denotes computed node embeddings, and DNE indicates node embeddings generated solely using DGI. The specific parameter configuration is shown in the following Table 4:

Table 1 shows the performance of our proposed method and other anti-money laundering baseline methods on the Elliptic dataset. The results show that our TFGAT model and the model optimized by the deep cyclic pseudo-label updating mechanism outperform other methods. After optimization by the deep cyclic pseudo-label updating mechanism, the performance of TFGAT is improved and the precision reaches 0.9814, the recall reaches 0.8390, and the F1 score reaches 0.9046.

Table 2 shows the performance of TFGAT with traditional label propagation methods. The results show that our deep cyclic pseudo-label updating mechanism outperforms other methods.

Table 3 shows the performance of TFGAT on the Elliptic dataset after deleting each component of TFGAT in turn.

The results show that the performance loss of the model without the Transformer component is the most serious. After DCPLU optimization, the Transformer can achieve 0.9789 precision, 0.8412 recall and 0.9048 f1.

Figures 6 and 7 respectively show each experiment’s ROC curves and confusion matrices. It can be observed that our proposed method outperforms other methods in terms of both performance and robustness, achieving an AUC of 0.9187.

Conclusion

In this paper, we propose a TFGAT model with a deep cyclic pseudo-label update mechanism (DCPLU) to capture hidden illegal Bitcoin transactions through various money laundering techniques and mitigate the impact of the sparse distribution of labelled transactions in the financial industry. To address the limitations of GAT node-level information extraction, our proposed TFGAT model extracts global information through a Transformer to enrich the extracted local information. To deal with the limited availability of labelled data in the expensive data labeling process, we introduce a deep cyclic pseudo-label update mechanism (DCPLU) to enhance the label distribution. DCPLU bypasses the model assumptions based on manifold structure or Euclidean distance, making pseudo-labels more suitable for AML tasks while enhancing model performance and maintaining the number of parameters of the existing model, so that the model can maintain the existing fast response time in the application scenario. Experimental results show that our model achieves state-of-the-art results.

Data availability

The sequence data supporting the results of this study are referenced from the Alibaba Tianchi public dataset and are available at the following link: https://tianchi.aliyun.com/dataset/110892.

References

Labib, N. M., Rizka, M. A. & Shokry, A. E. M. Survey of machine learning approaches of anti-money laundering techniques to counter terrorism finance. In Internet of Things–Applications and Future: Proceedings of ITAF 2019. 73–87 (Springer, 2020).

Force, F. A. T. What is money laundering. In Policy Brief July 1999 (1999).

Dumitrescu, B., Băltoiu, A. & Budulan, Ş. Anomaly detection in graphs of bank transactions for anti money laundering applications. IEEE Access 10, 47699–47714 (2022).

Fletcher, E., Larkin, C. & Corbet, S. Countering money laundering and terrorist financing: A case for bitcoin regulation. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2021.101387 (2021).

Beessoo, V. & Foondun, A. Money laundering through bitcoin: The emerging implications of technological advancement. In Available at SSRN 3468300 (2019).

Ziegeldorf, J. H., Matzutt, R., Henze, M., Grossmann, F. & Wehrle, K. Secure and anonymous decentralized bitcoin mixing. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 80, 448–466 (2018).

Guo, X., Lu, F. & Wei, Y. Capture the contagion network of bitcoin-evidence from pre and mid covid-19. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 58, 101484 (2021).

Han, J., Huang, Y., Liu, S. & Towey, K. Artificial intelligence for anti-money laundering: A review and extension. Digit. Finance 2, 211–239 (2020).

Youssef, B., Bouchra, F. & Brahim, O. State of the art literature on anti-money laundering using machine learning and deep learning techniques. In The International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Vision. 77–90 (Springer, 2023).

Ron, D. & Shamir, A. Quantitative analysis of the full bitcoin transaction graph. In Financial Cryptography and Data Security: 17th International Conference, FC 2013, Okinawa, Japan, April 1-5, 2013, Revised Selected Papers 17. 6–24 (Springer, 2013).

Weber, M. et al. Anti-money laundering in bitcoin: Experimenting with graph convolutional networks for financial forensics. arXiv: 1908.02591 (2019).

Mohan, A., Karthika, P. V., Sankar, P., Manohar, K. M. & Peter, A. Improving anti-money laundering in bitcoin using evolving graph convolutions and deep neural decision forest. Data Technol. Appl. https://doi.org/10.1108/DTA-06-2021-0167 (2022).

Alarab, I. & Prakoonwit, S. Graph-based lstm for anti-money laundering: Experimenting temporal graph convolutional network with bitcoin data. Neural Process. Lett. 55, 689–707 (2023).

Yang, G., Liu, X. & Li, B. Anti-money laundering supervision by intelligent algorithm. Comput. Secur. 103344 (2023).

Karim, R., Hermsen, F., Chala, S. A., De Perthuis, P. & Mandal, A. Scalable semi-supervised graph learning techniques for anti money laundering. IEEE Access (2024).

Li, X. et al. Diga: Guided diffusion model for graph recovery in anti-money laundering. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 4404–4413 (2023).

Zhou, J. et al. Graph neural networks: A review of methods and applications. AI Open 1, 57–81 (2020).

Jensen, R. I. T. & Iosifidis, A. Qualifying and raising anti-money laundering alarms with deep learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 214, 119037 (2023).

Yun, S., Jeong, M., Kim, R., Kang, J. & Kim, H. J. Graph transformer networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 32 (2019).

Luo, X., Han, X., Zuo, W., Wu, X. & Liu, W. Mlad 2: A semi-supervised money laundering detection framework based on decoupling training. In IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security (2024).

Lorenz, J., Silva, M. I., Aparício, D., Ascensão, J. T. & Bizarro, P. Machine learning methods to detect money laundering in the bitcoin blockchain in the presence of label scarcity. In Proceedings of the First ACM International Conference on AI in Finance. 1–8 (2020).

Lo, W. W., Kulatilleke, G. K., Sarhan, M., Layeghy, S. & Portmann, M. Inspection-l: Self-supervised gnn node embeddings for money laundering detection in bitcoin. Appl. Intell. 1–12 (2023).

Zagaris, B. Problems applying traditional anti-money laundering procedures to non-financial transactions,“parallel banking systems’’ and islamic financial systems. J. Money Laundering Control 10, 157–169 (2007).

Weber, M. et al. Scalable graph learning for anti-money laundering: A first look. arXiv preprint arXiv:1812.00076 (2018).

Huang, H., Wang, P., Zhang, Z. & Zhao, Q. A spatio-temporal attention-based gcn for anti-money laundering transaction detection. In International Conference on Advanced Data Mining and Applications. 634–648 (Springer, 2023).

Wei, T. et al. A dynamic graph convolutional network for anti-money laundering. In International Conference on Intelligent Computing. 493–502 (Springer, 2023).

Ouyang, S., Bai, Q., Feng, H. & Hu, B. Bitcoin money laundering detection via subgraph contrastive learning. Entropy 26, 211 (2024).

Wang, H. & Leskovec, J. Unifying graph convolutional neural networks and label propagation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.06755 (2020).

Bellei, C., Alattas, H. & Kaaniche, N. Label-gcn: An effective method for adding label propagation to graph convolutional networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.02153 (2021).

Ghayekhloo, M. & Nickabadi, A. Clp-gcn: Confidence and label propagation applied to graph convolutional networks. Appl. Soft Comput. 132, 109850 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Yuan, M., Zhao, C., Chen, M. & Liu, X. Integrating label propagation with graph convolutional networks for recommendation. Neural Comput. Appl. 34, 8211–8225 (2022).

Xie, T., Kannan, R. & Kuo, C.-C. J. Label efficient regularization and propagation for graph node classification. In IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (2023).

Tan, C., Chen, S., Geng, X., Zhou, Y. & Ji, G. Label enhancement via manifold approximation and projection with graph convolutional network. Pattern Recognit. 152, 110447 (2024).

Xiang, S. et al. Semi-supervised credit card fraud detection via attribute-driven graph representation. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 37, 14557–14565 (2023).

Navarro Cerdán, J. R., Millán Escrivá, D., Larroza, A., Pons-Suñer, P. & Pérez Cortés, J. C. A deep gcn approach based on multidimensional projections and classification to cybercrime detection in a true imbalanced problem with semisupervision. In Available at SSRN 4519572 (2023).

Tang, J., Zhao, G. & Zou, B. Semi-supervised graph convolutional network for ethereum phishing scam recognition. In Third International Conference on Electronics and Communication; Network and Computer Technology (ECNCT 2021). Vol. 12167. 369–375 (SPIE, 2022).

Zhang, S., Suzumura, T. & Zhang, L. Dyngraphtrans: Dynamic graph embedding via modified universal transformer networks for financial transaction data. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Smart Data Services (SMDS). 184–191 (IEEE, 2021).

Vassallo, D., Vella, V. & Ellul, J. Application of gradient boosting algorithms for anti-money laundering in cryptocurrencies. SN Comput. Sci. 2, 1–15 (2021).

Marasi, S. & Ferretti, S. Anti-money laundering in cryptocurrencies through graph neural networks: A comparative study. In 2024 IEEE 21st Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC). 272–277 (IEEE, 2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted without pre-registration and utilises original pseudo-label updating frameworks that have not been previously published. The authors extend their gratitude to Dr. Meng Li for providing computational resources and technical guidance. Special thanks are owed to Mr. Lu Jia and Miss XinQiao Su for their contributions to dataset curation and algorithmic validation.

Funding

This work was supported by the Foundation of Hebei Educational Department (No. ZD2021319) and Hebei University of Economics and Business (No. 2024ZD10).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L. conceptualised the study, designed the experimental framework, and performed the data acquisition. L.J. executed the experiments, carried out the initial analysis, and drafted the manuscript. X.S. conducted in-depth data analysis, provided critical insights, and suggested substantial revisions to enhance the manuscript. All authors actively contributed to discussions throughout the research process and have thoroughly reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, M., Jia, L. & Su, X. Global-local graph attention with cyclic pseudo-labels for bitcoin anti-money laundering detection. Sci Rep 15, 22668 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08365-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08365-9