Abstract

This study examines the impact of High-Performance Work Systems on the Innovative Behavior of IT employees in China’s smartphone industry, drawing on Social Cognitive, Psychological Empowerment, and Social Information Processing Theories. Using a mixed-methods approach that combines Structural Equation Modeling and Fuzzy-Set Qualitative Comparative Analysis, this study is based on survey data from 481 full-time IT employees from leading smartphone companies in China. A moderated mediation model is developed to reveal how High-Performance Work Systems enhance employees’ perceptions of work meaning, competence, work impact, and self-determination, thereby fostering Innovative Behavior. Notably, Power-Distance Orientation moderates the relationship between High-Performance Work Systems and Innovative Behavior, particularly in terms of work meaning and competence. In high Power-Distance Orientation contexts, employees are more inclined to defer to authority, which reduces the motivational effect of High-Performance Work Systems on Innovative Behavior. The findings highlight the importance of optimizing human resource management practices to strengthen psychological empowerment, as a means of enhancing innovation and overall organizational performance. This study offers valuable practical implications for the highly competitive and rapidly evolving smartphone industry, providing insights into how organizations can effectively leverage High-Performance Work Systems to drive innovation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In today’s digital and knowledge-based economy, innovation is widely viewed as the central engine for maintaining a sustainable competitive advantage1. Organizations that effectively encourage innovative behavior (IB) among their employees tend to show greater adaptability, foresight, and competitiveness in global markets2. However, many companies, especially those operating in high-pressure and rapidly changing industries, still find it challenging to establish a sustainable mechanism for promoting innovation3. In response, High-Performance Work Systems (HPWS), a strategic and systematic approach to human resource management (HRM), have increasingly gained attention as an effective way to foster innovation within organizations4.

Among various HRM practices, HPWS is considered strategically valuable for stimulating IB among employees. Unlike traditional methods such as isolated training sessions, performance appraisals, or incentive programs, HPWS uses a systemic and coordinated approach. Through the ability–motivation–opportunity (AMO) framework, HPWS simultaneously enhances employees’ cognitive evaluations, intrinsic motivation, and willingness to innovate. Specifically, HPWS sends clear organi-zational signals of trust, support, and development through institutionalized training, clear role definitions, and participative practices. These signals help employees develop positive perceptions about their work. Unlike isolated HR practices, employees perceive HPWS as a coherent and stable organizational signal, which fosters stronger psychological attachment and long-term willingness to innovate5.

This interpretation has been consistently supported by empirical studies. For instance, evidence from manufacturing, project-based, and service industries shows that HPWS significantly outperforms standalone incentive or appraisal practices in promoting proactive behavior, autonomous learning, and exploratory innovation among employees6,7,8. These findings highlight the unique strength of HPWS in aligning institutional design with employee motivation. From both organizational and cognitive perspectives, HPWS appears especially effective at activating employees’ innovative capacity when compared to conventional HRM practices. Notably, this effect becomes more pronounced in knowledge-driven environments such as universities6,9, high-tech manufacturing and knowledge-intensive service sectors10, and the IT industry11, where intellectual capital is a primary driver of performance.

However, despite this growing evidence base, some studies report inconsistent findings regarding the impact of HPWS on.

IB, prompting a closer examination of its underlying mechanisms. Certain studies indicate that the expectation of rewards may cause employees to focus more heavily on short-term goals rather than deep thinking and breakthrough solutions12. Additionally, performance-based assessments and reward systems can sometimes increase employee stress and reduce job satisfaction, negatively affecting creative performance13. From a process theory viewpoint, some researchers argue that HPWS can intensify organizational control over employees, reducing autonomy and limiting their capacity for self-management, which ultimately hampers innovation14. These contradictory findings suggest that how employees perceive, interpret, and internalize HPWS may significantly influence its outcomes—making it essential to investigate psychological or contextual factors that shape these responses.

Psychological empowerment (PE) has emerged as a central mechanism explaining how HPWS influences IB. Social cognitive (SC) theory15 highlights that employees actively interpret organizational signals rather than passively accepting them, and their behaviors reflect how they process and interpret external stimuli. HPWS communicates empowering signals, which help employees perceive greater meaningfulness, competence, autonomy, and influence—key dimensions of PE16. These cognitive assessments determine whether employees internalize organizational systems positively, shaping their intrinsic motivation and IBs.

Substantial empirical research shows PE drives employee initiative and IB. Employees who feel psychologically empowered typically demonstrate greater initiative, share ideas more actively, and engage enthusiastically in solving complex problems17,18. Research by Mirza et al. (2024) confirms PE significantly mediates the relationship between HPWS and employees’ creative process engagement. Their study clearly indicates PE enhances employees’ enthusiasm for problem identification, information search, and idea generation19. Similarly, Abbasi et al. (2020) found PE not only promotes IB but also positively influences employees’ willingness to share knowledge20. This makes employees more inclined to share insights and expertise with colleagues, providing crucial support for the organization’s long-term development.

However, while PE offers valuable insight into how HPWS motivates employees, its effects may still depend on individual and cultural differences. Employees’ cultural orientations, particularly power distance orientation (PDO), significantly influence how they interpret and respond to empowerment signals from organizations. According to social information processing (SIP) theory21, employees’ cultural backgrounds affect their perception and response to organizational systems. Employees in high-power-distance cultures typically prefer hierarchical authority and may hesitate to act independently, even if formally empowered by the organization, due to uncertainty or insecurity22. As a result, HPWS may not effectively stimulate innovation among these employees. Yet, other research suggests that employees with high PDO might respond more positively to formal empowerment structures, as they trust clear authority-based rules23. Consequently, once the organizational structures are explicitly defined, these employees could become more active in pursuing organizational innovation goals22,24,25. These insights suggest that PDO may either amplify or diminish the effectiveness of HPWS, depending on how empowerment mechanisms are interpreted.

Given these theoretical complexities, there is a need to contextualize the HPWS–PE–IB relationship in real-world, high-stakes industries. The smartphone industry in China provides an ideal context for exploring these dynamics. China’s smartphone industry plays a vital role in the country’s digital economy, contributing 44.5% of national GDP in 202326. Under national strategies such as “Made in China 2025” and the “14th Five-Year Plan,” the industry is shifting from cost-based competition to innovation-driven development. However, this transformation has exposed three core structural challenges. First, the industry faces rising external uncertainty. In 2023, smartphone exports dropped to USD 138.8 billion, the lowest in 13 years, highlighting its vulnerability to global market fluctuations27. Second, domestic firms still depend heavily on foreign suppliers for essential technologies, including chipsets and operating systems28,29. This dependence limits innovation autonomy and increases exposure to geopolitical and supply chain risks. Third, the sector’s ability to innovate relies largely on IT professionals, whose expertise, creativity, and collaboration drive internal breakthroughs30. Internal knowledge sharing has become more important than external technology acquisition. Yet these employees work under constant pressure, with long hours, fast-paced technical updates, and demanding performance metrics. These factors erode their mental well-being and reduce their sustained capacity to innovate.

In this high-pressure environment, HRM strategies must take a more proactive role in supporting employees’ PE and fostering innovation. IT professionals, as the core drivers of digital transformation, are particularly sensitive to the design and effectiveness of HR systems. HPWS presents a strategically promising solution to address these challenges by enhancing employees’ intrinsic motivation and innovation capacity. However, despite its theoretical potential, current research still lacks a comprehensive understanding of how HPWS functions in such demanding, knowledge-intensive settings—especially how it interacts with PE and PDO to shape IB. To advance both theoretical development and practical application, it is therefore critical to identify and address several key research gaps that remain underexplored.

Specifically, four major limitations can be observed in the current literature. First, although HPWS research in China has received some attention, most studies focus on manufacturing, healthcare, and service industries31,32,33. There is limited exploration in technology-intensive sectors such as the smartphone industry, which is characterized by rapid technological

change, strong competition, and a high reliance on innovation. The unique HRM challenges in this sector remain underexplored. Second, research on IT employees as a distinct workforce is scarce. These employees play a central role in technological advancement and innovation. They operate in high-pressure environments that demand continuous learning, autonomy, and adaptability. Unlike traditional workers, they respond differently to HRM systems, yet little is known about how HPWS can support their innovation behavior under such conditions. Third, while PE is widely recognized as a mediator between HPWS and IB, most studies treat it as a single construct. This overlooks potential differences across its four dimensions—work meaning, competence, impact, and self-determination. These dimensions may be influenced differently by employees’ PDO, but few studies have examined this interaction, limiting understanding of how HPWS produces its effects in varying cultural contexts. Fourth, most HPWS studies rely on variable-centered methods such as structural equation modeling (SEM). Although useful for testing linear relationships, SEM is limited in capturing the complexity of causal interactions in real-world contexts. Methods like Fuzzy-set Qualitative Comparative Analysis (fsQCA) allow for the identification of multiple causal pathways and asymmetric relationships, but their use in HRM research remains limited. The lack of integration between SEM and fsQCA creates a methodological gap.

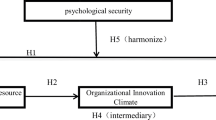

To bridge these research gaps, this study develops a moderated mediation model to analyze how HPWS promotes IB through the four dimensions of PE and how PDO shapes these effects. It focuses on IT employees in China’s smartphone industry. The research questions are as follows. Q1: What is the relationship between HPWS and IB? Q2: Do the four dimensions of PE (work meaning, competence, work impact, self-determination) mediate this relationship? Q3: How does PDO moderate these effects?

To address these questions, the study establishes three primary objectives. First, it investigates the direct effect of HPWS on IB among IT professionals in China’s smartphone industry. Second, it examines the mediating role of PE, focusing on how employees’ perceptions of work meaning, competence, impact, and self-determination explain the mechanisms through which HPWS influences IB. Third, it analyzes how PDO, defined as employees’ individual attitudes toward authority and hierarchical relationships, moderates these relationships by affecting how empowerment initiatives are interpreted and internalized. Through these interconnected objectives, the study illuminates both psychological processes and cultural contingencies that shape the effectiveness of HR practices in knowledge-intensive organizational environments.

This study holds significant theoretical relevance. First, it extends HPWS research into the smartphone industry and IT workforce, which operate in innovation-intensive and high-pressure settings. Second, it integrates SC, PE, and SIP theories to build a comprehensive framework that explains how HPWS influences IB through psychological and cognitive mechanisms while accounting for cultural variation. SC theory explain how employees interpret organizational signals, PE theory describes the structure of empowerment, and SIP theory accounts for the cultural lens through which employees evaluate those signals. Third, unlike previous studies that treat PE as a single construct, this study analyzes each dimension separately. This approach reveals how different aspects of empowerment may respond to HPWS and interact with cultural orientations like PDO. Fourth, methodologically, the study combines SEM and fsQCA. This integration captures both linear effects and non-linear patterns, providing a richer understanding of how HPWS functions across contexts.

From a practical standpoint, the study provides insights at multiple levels. At the industry level, it supports China’s shift from cost-driven to innovation-led development by offering HRM strategies tailored to a key technology sector. At the organizational level, the study emphasizes the need to tailor HPWS to the specific demands of high-pressure, knowledge- intensive environments. At the employee level, it highlights how HRM practices can better serve IT professionals, who are essential to driving technological progress.

Literature review

The link between HPWS and IB

HPWS have gained increasing scholarly interest as a strategic human resource architecture that facilitates innovation at the employee level. Typically composed of mutually reinforcing practices, such as results-oriented appraisals, training programs, employment security, and participative decision-making34. HPWS are thought to enhance employees’ ability, motivation, and opportunity to engage in innovative behavior. Over time, this relationship has been framed through diverse theoretical lenses. Early research primarily drew on Social Exchange Theory, emphasizing how fair and supportive HR systems generate reciprocal commitment and proactive behaviors35,36. HPWS enhance this exchange by creating systems employees see as trustworthy and empowering37. Recent evidence shows that HRM promote intrinsic motivation by fulfilling employees’ psychological needs, including autonomy, competence, and relatedness, as proposed by Self-Determination Theory. This aligns with the resource-based view, which frames these systems as internal capabilities that sustain competitive advantage by enhancing employee resilience and performance38. In dynamic environments, Dynamic Capability Theory positions HPWS as tools for enhancing organizational agility by continuously strengthening employees’ adaptive capacity through learning and participation39.

Empirical findings have provided robust support across varied sectors and cultures. For example, research in the phar- maceutical sector showed that HPWS enhanced employees’ psychological capital, such as optimism and resilience, thereby encouraging them to explore new ideas40. Similar effects were found in high-tech and public-sector R&D organizations, where team-based HPWS were linked to greater exploratory learning and autonomous decision-making6,41. In Czech SMEs, HPWS promoted both inbound and outbound innovation by strengthening internal knowledge sharing and boosting problem-solving capabilities10. In China and Jordan, the effects of HPWS on innovation were further enhanced when combined with strong organizational support and employee engagement4,42.

Although HPWS are widely recognized for promoting innovation, recent studies suggest that their effectiveness may be context-dependent and, in some cases, counterproductive. In highly performance-driven environments, employees may interpret HPWS as tools for output control rather than developmental support, which leads them to prioritize short-term results over original or high-risk ideas43. When organizational climates emphasize internal competition, HPWS may intensify pressure on employees, encouraging knowledge hoarding and reducing collaboration, thereby disrupting the flow of ideas and weakening trust44. Furthermore, if employees perceive a gap between promised support and actual managerial practices, such as insufficient feedback or one-sided performance evaluations, psychological contract breaches may occur13. This sense of unfulfilled expectations often reduces motivation and discourages discretionary efforts like innovation. In high-stress sectors or low-trust workplaces, HPWS may even become a source of strain rather than empowerment, increasing emotional fatigue and disengagement45. Technological factors also shape these dynamics. While IT systems that support exploration can enhance creativity, those focused on routine optimization may create rigidity42. Over time, this may reduce openness to new thinking and limit the organization’s adaptability.

Based on these insights, this study proposes:

H1

HPWS positively influence employees’ IB.

The mediation effect of PE

PE is increasingly seen as a central mechanism that explains how HPWS influence IB. Scholars drawing on self-determination theory and the resource-based view have shown that HPWS improve employees’ perceptions of meaning, competence, autonomy, and impact by providing structured training, performance feedback, and participatory decision-making opportunities37,46. These practices fulfill core psychological needs and reinforce employees’ intrinsic motivation. Empirical research supports this view. In the food service sector, HPWS enhanced employees’ affective commitment by fostering a stronger sense of belonging and purpose37. Similarly, in the pharmaceutical industry, HPWS were found to strengthen technical confidence and task-related competence through targeted training47.

Despite these benefits, some studies report that the effects of HPWS on PE are not always positive. In high-pressure or low-trust environments, HPWS may increase workload without providing adequate support. For instance, Yu et al. (2025) found that banking employees in China experienced heightened stress and diminished autonomy as a result of HPWS, which ultimately led to emotional exhaustion48. When employees perceive these practices as controlling or performance-pressuring rather than supportive, key psychological resources such as hope and resilience may be depleted45. Similarly, in Indonesian service organizations, the absence of supervisor support and psychological safety intensified the negative impact of HPWS and contributed to burnout49.

Once established, PE becomes an important predictor of IB. But previous literature indicates that the influence of PE on IB is highly context dependent. On the one hand, organizational support is a key focus in this field. Empirical studies by Almulhim (2020) suggest that in contexts where employees experience high autonomy and organizational support, PE can enhance their willingness to engage in knowledge sharing, thus fostering innovation50. However, in the absence of sufficient resource backing or managerial recognition, PE may not necessarily translate into innovative outcomes41. This dual effect of PE indicates that when empowerment perceptions are not matched by adequate resource support, PE may negatively affect IB37,42. One the other hand, leadership styles and task characteristics have also been shown to significantly influence. Research by Stanescu et al. (2021) demonstrated that under transformational leadership, PE enhances employees’ self-efficacy and goal orientation, thus leading to higher levels of innovation output51. However, when employees’ perceptions of empowerment conflict with organizational expectations, this heightened sense of autonomy can reduce employees’ alignment with organizational goals, ultimately impacting overall task performance and innovation capacity46. Thus, based on the two aspects, the relationship between PE and IB is not linear but is influenced by a multitude of interacting factors.

These findings suggest that PE serves as a bridge between HPWS and innovation. Multiple studies confirm this mediating effect. Studies grounded in the componential theory of creativity and the AMO (ability–motivation–opportunity) framework suggest that PE enhances employees’ intrinsic motivation, translating HR investments into innovation at both the individual and organizational levels. For instance, evidence from the service and manufacturing sectors shows that PE significantly mediates the effect of HPWS on innovative work behavior, particularly in contexts where HR practices are complemented by supervisory support and opportunities for voice participation19,52. Moreover, research indicates that PE is not only an individual psychological construct but also functions collectively to convert HRM practices into organizational innovation capabilities. A recent large-sample study confirmed that PE and innovative behavior together serve as serial mediators between HR systems and firm-level innovation outputs, highlighting the strategic relevance of empowerment in innovation systems53. This is echoed by findings demonstrating that HRM-driven psychological empowerment fosters knowledge sharing and cognitive engagement, enabling the transformation of organizational resources into creative outcomes46,50.

We accordingly propose the following hypotheses:

Hypotheses 2

HPWS positively influences the four dimensions of PE: work meaning, competence, work impact, and self-determination (H2a-2d).

Hypotheses 3

Each dimension of PE positively affects IB (H3a-3d).

Hypotheses 4

The four dimensions of PE mediate the relationship between HPWS and IB (H4a-4d).

The moderation effect of PDO

Based on recent research and supported by insights from SIP theory, PDO plays a critical and context-sensitive role in how employees interpret and respond to organizational practices such as HPWS. According to SIP theory, individuals rely on cues from their social and organizational environments to understand workplace structures and behavioral expectations21. In hierarchical cultures like China, PDO influences whether employees perceive HRM practices as supportive or controlling54,55.

Most empirical studies suggest a predominantly negative moderating effect of PDO on innovation outcomes. For example, Li and Yeh (2023) demonstrated that employees in low PDO environments are more willing to share ideas and participate in decision-making, which enhances innovation, whereas high PDO environments discourage open communication and initiative55. Xu et al. (2023) reinforced this finding by showing that rigid hierarchies in high PDO contexts slow down decision-making processes, thus undermining sustainable innovation efforts across Asian economies56. Further studies highlight that high PDO often suppresses collaborative innovation. In cross-national contexts, such as Chinese firms operating in Malaysia, Rasiah and Ren (2023) found that hierarchical structures reduced autonomy and constrained creativity57. Similarly, Rasheed et al. (2024) noted that in Pakistan’s IT industry, high PDO limited the effectiveness of HR flexibility, ultimately diminishing firm-level innovation58. Ma et al. (2023) also observed that lower PDO enhances cross-departmental collaboration, which supports broader organizational innovation strategies59. These studies underscore the restrictive nature of high PDO in dynamic, knowledge-intensive sectors where adaptability is critical.

However, contrasting evidence suggests PDO is not inherently detrimental. Hofstede (1984) originally theorized that high PDO can foster trust in authority and clarify organizational hierarchies, which might enhance performance under certain conditions. In highly structured or risk-averse environments, goal alignment and behavioral consistency facilitated by high PDO may yield positive effects. For instance, Alper (2020) argued that authoritative leadership and structured communication in high PDO cultures can improve innovation efficiency by clearly defining expectations60. Likewise, Wang and Guan (2018) found that Chinese firms benefitted from PDO’s ability to create clear role boundaries, which fostered compliance and motivation24. This dual perspective is echoed in Bowling et al. (2015), who found that PDO can help buffer workplace dissatisfaction by reinforcing commitment to organizational goals61.

Based on these contrasting perspectives, we propose Hypotheses 5a–5e:

H5a

PDO moderates the relationship between HPWS and work meaning, such that higher PDO weakens this relationship.

H5b

PDO moderates the relationship between HPWS and competence, such that higher PDO weakens this relationship.

H5c

PDO moderates the relationship between HPWS and work impact, such that higher PDO weakens this relationship.

H5d

PDO moderates the relationship between HPWS and self-determination, such that higher PDO weakens this relationship.

H5e

PDO moderates the relationship between HPWS and IB.

Method

Research design

This study employs a mixed-methods design, combining SEM with fsQCA to overcome the limitations of traditional linear models and enhance causal inference. SEM remains a prevalent technique for testing hypothesized relationships and assessing path coefficients; however, it assumes symmetry and linearity, often failing to capture feedback loops and complex interactions within organizational systems62,63. Moreover, SEM focuses on average effects across a population, which can obscure meaningful causal heterogeneity64.

To address these gaps, fsQCAis incorporated as a complementary tool. Unlike SEM, fsQCA identifies multiple, non-linear, and asymmetric causal pathways, allowing for the discovery of equifinal conditions that lead to the same outcome63. It is also particularly useful in addressing methodological issues such as endogeneity, measurement error, and reverse causality, which often challenge the validity of causal claims in social science research65,66.

Research model

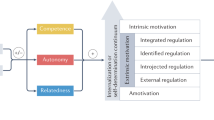

This study employs SC Theory as the dominant theoretical foundation to construct a comprehensive and explanatory model. Unlike incentive-based frameworks such as Social Exchange Theory or Dynamic Capability Theory, SC Theory posits that employees are active cognitive agents who dynamically interpret and internalize organizational signals through subjective cognitive processes, rather than passive recipients of organizational systems15,37,39,67. Within this framework, HPWS represent strategic environmental stimuli whose motivational impact depends fundamentally on employees’ cognitive processing of these signals. SC Theory thus serves as the primary theoretical pillar that provides both the cognitive foundation for understanding employee behavioral responses and the overarching analytical structure for this research.

Building upon this SC Theory foundation, PE Theory is incorporated as a supporting theoretical perspective to specify the "internal cognitive mechanisms" central to SC Theory16,18. As an extension of the SC Theory framework, PE Theory enables a detailed analysis of how HPWS activates distinct psychological dimensions—specifically, employees’ perceptions of meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact at work—which subsequently foster innovative behavior. These dimensions represent concrete manifestations of the cognitive processes theorized in SC Theory.

Within the SC Theory-dominant framework, SIP Theory is integrated as an auxiliary theory to address the "situational cognitive processing" component21,25. This supporting theory illuminates how PDO, as a cultural-psychological variable, moderates employees’ cognitive interpretation of HPWS, thereby providing contextual boundary conditions for the SC Theory framework.

In summary, this study establishes a hierarchical theoretical structure with SC Theory as the core theoretical lens, sup-plemented by PE Theory and SIP Theory at the mechanism and situational levels respectively. These supporting theories operate within the SC Theory framework, enriching its explanatory power regarding the HPWS-innovation relationship. This core-supporting theoretical integration creates an explanatory system with both theoretical depth and breadth, advancing our understanding of organizational behavior beyond what single-theory approaches could offer. Figure 1 presents this SC Theory-centered conceptual framework, while Fig. 2 operationalizes it into an empirical model.

Variable measurement and research instrument

To ensure the validity and reliability of the measurement tools, this study followed a rigorous process for questionnaire design: (1) a comprehensive review of existing literature to select established and validated scales; (2) adoption of previously translated Chinese versions to minimize translation bias; and (3) confirmation that no item modifications were necessary based on the pilot results. All variables were measured using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

HPWS were assessed using the 7-item “best HRM practices” scale developed by Delery and Doty (1996), which has demonstrated reliability and validity in Chinese organizational settings68. A representative item includes: “Extensive training programs are provided for individuals in my job.”

IB was measured using the six-item scale developed by Scott and Bruce (1994), capturing both idea generation and implementation. This scale has been widely applied in research involving high-tech employees in China43. A sample item is: “I generate creative ideas.”

PE was measured using Spreitzer’s (1995) 12-item scale, comprising four dimensions: meaning, competence, self- determination, and impact, with three items for each dimension. It has been extensively validated in China’s different organizational settings69. Representative items include: “The work Ido is very important to me” (meaning); “Ihave mastered the skills necessary for my job” (competence); “My impact on what happens in my department is large” (impact); and “I have significant automony in determining how Ido my job” (self-determination).

PDO was measured using the six-item scale developed by Dorfman and Howell (1988), frequently used in Chinese cultural research70. A typical item reads: “I totally agree with managers and almost never say ‘no’ to their decisions.”

Control variables included gender, age, salary, education level, position, and tenure. These demographic factors have been shown to influence IB in prior research71, and were included to reduce omitted variable bias.

Sampling, sample size, data collection and profiles of respondents

This study targeted IT professionals employed in China’s smartphone sector, a knowledge-intensive industry undergoing rapid innovation. Given the large population of IT workers in this field, the sample size was estimated using Raosoft’s sample size calculator. For populations exceeding 20,000, a minimum of 384 responses ensures statistical reliability. Accounting for an average individual-level response rate of 52.7%72, 728 participants were approached.

Data were collected using an online survey. After screening for completeness and validity, 481 usable responses were retained for analysis. The final sample consisted omf 375 male (77.96%) and 103 female (21.41%) respondents, with three respondents preferring not to disclose gender. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to over 40 years.

Descriptive stati including mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis, were calculated using SmartPLS 4.0. As shown in Table 1, all variables exhibited acceptable dispersion levels. The absolute values of skewness (< 3) and kurtosis (< 10) meet the normality criteria recommended by Kline73, indicating that the data were approximately normally distributed and suitable for subsequent SEM and fsQCA analysis.

Factor analysis and common method bias assessment

To assess the factorial structure of the measurement model, both exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were conducted sequentially. EFA was used to identify the underlying factor structure, while CFA validated the factor solution and assessed model fit74. The results of Harman’s single-factor test indicated that the first factor accounted for 32.21% of the total variance, which is well below the 50% threshold, suggesting no significant common method bias75. Additionally, all variance inflation factor (VIF) values were below 3.3, confirming the absence of multicollinearity76.

The CFA results revealed a good model fit, with χ2/df = 1.243, GFI = 0.933, RMSEA = 0.023, and other fit indices (RMR, CFI, NFI, NNFI) exceeding the conventional cutoff of 0.90, thereby demonstrating strong construct validity77,78.

Findings

Measurement model

Testing reliability and validity

Following the guidelines proposed by Hair et al. (2019), the measurement model was assessed through multiple indicators of reliability and validity. Reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR), while convergent validity was assessed through average variance extracted (AVE). All constructs, including HPWS, PE, IB, and PDO, exhibited Cronbach’s alpha and CR values above the 0.70 benchmark, indicating strong internal consistency. Moreover, all AVE values exceeded 0.50, confirming sufficient convergent validity78.

Testing discriminant validity

Discriminant validity is essential for ensuring that each construct in a structural equation model represents a unique concept. Without sufficient discriminant validity, overlapping constructs may compromise the integrity of the model and the interpretation of its results. This study employed three widely accepted methods to assess discriminant validity: cross-loadings, the Fornell–Larcker (FL) criterion, and the Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio.

The cross-loadings analysis, presented in Table 1, shows that each item loads higher on its corresponding construct than on any other construct, supporting item specificity and construct distinctiveness.

Table 2 reports the Fornell–Larcker results. For each construct, the square root of its AVE (shown in bold on the diagonal) exceeds its correlations with other constructs (off-diagonal values), confirming adequate discriminant validity across all latent variables79,80.

The HTMT values, listed in Table 3, provide further support. All HTMT ratios fall below the conservative threshold of 0.90, with the highest being 0.813. This result aligns with the recommendations by Henseler et al. (2015) and indicates that no critical discriminant validity issues are present in the model64.

Testing predictive relevance

This study assesses predictive relevance and explanatory power using Q2 and R2, two key indicators in structural equation modeling. According to Hair et al. (2019), R2 values of 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25 reflect substantial, moderate, and weak explanatory strength, respectively. As shown in Table 4, the R2 results indicate that HPWS and its related constructs exhibit moderate to weak levels of explained variance. These findings suggest that the model offers a reasonable level of explanatory adequacy for the dependent variables.

To evaluate predictive accuracy, the study also examines the Q2 statistic. Values greater than zero indicate meaningful predictive relevance, with 0.25 and 0.50 marking medium and high relevance, respectively. All constructs in this study yield positive Q2 values, confirming the model’s predictive capacity.

Hypotheses testing

This section reports the direct effects within the moderated mediation model, based on the path coefficients estimated through SEM. All relationships demonstrated statistical significance, validating the core hypotheses of the study.

Direct effects

Figure 3 illustrates the results of direct hypothesis testing. HPWS significantly predicted IB (H1: β = 0.601, p < 0.001), supporting the central premise of this study. HPWS also showed a positive effect on each PE dimension: work meaning (H2a: β = 0.401, p < 0.001), competence (H2b: β = 0.610, p < 0.001), work impact (H2c: β = 0.506, p < 0.001), and self-determination.

(H2d: β = 0.444, p < 0.001). These findings suggest that HPWS effectively cultivates psychological empowerment among IT professionals.

Each PE dimension also contributed significantly to IB. Specifically, work meaning (H3a: β = 0.153, p < 0.005), competence (H3b: β = 0.219, p = 0.000), work impact (H3c: β = 0.289, p < 0.001), and self-determination (H3d: β = 0.143, p < 0.005) all exhibited meaningful positive relationships with IB. These results support the theoretical assumption that empowered employees are more inclined to engage in innovation-related behaviors.

Hypotheses testing of indirect relationships

To test mediation and moderated mediation effects, this study employed the PROCESS macro, which also enabled simple slope analysis to visualize interaction dynamics. Table 5 summarizes the test outcomes, while Figure 4 presents the simple slope plots.

The mediation analysis supported all four hypotheses related to the indirect effects of PE dimensions. Specifically, work meaning (β = 0.069, p = 0.008), competence (β = 0.152, p < 0.001), work impact (β = 0.163, p < 0.001), and self-determination (β = 0.072, p = 0.009) significantly mediated the effect of HPWS on IB. These results indicate that HPWS shapes IB not through a singular mechanism but through multiple psychological pathways that reflect employees’ internalized perceptions of their roles and contributions.

The moderated mediation results revealed partial support for the hypotheses. The interaction between HPWS and PDO.

significantly influenced the mediation pathway through work meaning (H5a) and competence (H5b). As PDO increased, the indirect effects of HPWS on IB via work meaning declined from 0.089 to 0.048, with an index of moderated mediation at − 0.020 (p < 0.1). Similarly, for competence, the indirect effect decreased from 0.190 to 0.109 as PDO increased, with an index of − 0.041 (p < 0.1). These findings suggest that in high power distance contexts, employees may perceive less autonomy or confidence even when exposed to empowerment-oriented HR practices, thereby weakening the motivational force of PE.

However, the moderating effect of PDO on the mediation pathways via work impact (H5c) and self-determination (H5d) was not statistically significant. This non-significance can be attributed to the structural constraints of high power distance cultures. In such environments, authority is centralized, and employees often perceive limited influence over organizational decisions. Even when HPWS provide empowerment opportunities, employees may not internalize a sense of actual impact, weakening the pathway from work impact to IB81. Similarly, high PDO contexts foster a norm of deference to authority, where autonomy is neither expected nor actively exercised. As a result, even when self-determination is formally offered, employees may refrain from taking initiative or engaging in discretionary innovation efforts, rendering the self-determination–IB pathway ineffective82.

Reanalysis of the data using fsQCA variable calibration

This study investigated HPWS, work meaning, competence, work impact, self-determination, and PDO as condition variables, with IB as the outcome. Before performing fsQCA, all variables required calibration. The mean score for each variable represented its observed value. Following Ragin’s (2008) guidelines, the 95th percentile was set as the threshold for full membership, the 50th percentile as the crossover point, and the 5th percentile as the threshold for full non-membership. To avoid the software’s exclusion of cases with membership scores exactly at 0.500, a small constant (0.001) was added to those scores to preserve the effective sample size.

Analysis of necessary conditions

The necessity analysis tested each condition separately to evaluate whether any variable consistently appeared when the outcome was present. Consistency served as the key criterion. A consistency value above 0.90 indicates that a condition is necessary for the outcome to occur. As shown in Table 6, all variables scored below the 0.90 threshold. This finding suggests that no single factor, on its own, is required to explain IB. Instead, IB arises from the combination of multiple conditions acting together.

Analysis of conditional configuration

This study used a frequency threshold of 3 for the truth table design because of the large sample size. It also set the raw consistency threshold at 0.8 to make sure the configurations had strong explanatory power63. The PRI consistency threshold also stood at 0.8 to avoid the problem of "simultaneous subset relations." Table 7 shows seven different configurations that affect IB. The solution consistency equals 0.958, much higher than the 0.8 threshold. The solution coverage equals 0.807, exceeding the 0.5 standard. All these configurations show high consistency based on these results.

fsQCA results as a support to SEM findings

The fsQCA findings complement and extend the results obtained from SEM, offering a more nuanced understanding of how various configurations of conditions lead to IB. Consistent with SEM results, fsQCA identifies HPWS as a core contributor to innovation across several configurations (e.g., S1–S4), confirming its central role in promoting IB across diverse organizational scenarios.

In relation to mediation, the fsQCA output corroborates the SEM findings that all four PE dimensions—work meaning, competence, work impact, and self-determination—mediate the effect of HPWS on IB. These psychological constructs frequently appear as either core or contributing conditions in different configurations, underscoring their importance in translating HR systems into employee-level innovation outcomes.

The analysis of moderated mediation effects further reinforces the SEM findings. In low power distance environments (e.g., S4), fsQCA reveals that work meaning and competence consistently emerge as key pathways through which HPWS promotes IB. However, in high power distance contexts (e.g., S5), although structural rules may still support innovation, they tend to weaken the motivational impact of work meaning and competence. These results echo the SEM evidence, suggesting that PDO significantly moderates the mediating effects of PE, altering how HPWS translates into innovation.

fsQCA results as a supplement to SEM findings

The fsQCA findings extend the SEM analysis by identifying dominant innovation pathways and revealing the interaction patterns among key conditions. Two major configurations stand out. The HPWS-dominant pathway (S1–S4) highlights HPWS as a central driver of innovation, supported by competence and self-determination. In this configuration, peripheral factors such as work meaning and work impact further reinforce employee engagement and clarity. This pathway proves particularly effective in environments characterized by low power distance and sufficient resources.

In contrast, the rule-reinforced pathway (S5–S6) reflects a different innovation logic. Here, power distance plays a compensatory role in contexts where PE is weaker. This pathway emphasizes structure, formality, and institutional reinforcement. It performs well in hierarchical organizations with limited resources, especially when innovation goals are narrow in scope and short-term in nature.

Beyond identifying these configurations, fsQCA reveals patterns that challenge and complement the SEM model. First, it identifies non-linear pathways. For instance, in S6, competence and self-determination foster IB even in the absence of HPWS. This suggests that innovation can arise through alternate routes and that relying solely on HPWS may overlook other critical drivers. Second, fsQCA highlights the dual role of power distance. In hierarchical contexts, it enables rule-based innovation (e.g., S5), while in low power distance cultures, it facilitates autonomy-driven innovation (e.g., S4). These results align with recent scholarship on the contingent nature of power distance in shaping innovation outcomes55,56.

Discussion

This study employed both SEM and fsQCA to examine how HPWS shape employees’ IB through the mediating role of PE, while also evaluating the moderating influence of PDO.

The findings strongly support H1. SEM results indicate a significant positive effect of HPWS on IB (β = 0.531, p < 0.05), while fsQCA identifies HPWS as a core condition in multiple configurations. These results underscore HPWS’s central role in enhancing innovation, aligning with AMO theory and prior research5,6. A major contribution here is the study’s focus on IT professionals in China’s smartphone industry, a talent-intensive group operating in high-pressure, innovation-driven environments.

Hypotheses H2 through H4 are also confirmed. Each of the four PE dimensions significantly mediates the relationship between HPWS and IB. This not only strengthens the foundation of PE theory but also contributes by unpacking its dimensional effects. Previous studies often treated PE as a single construct19, but our findings demonstrate that each dimension—work meaning, competence, self-determination, and impact—supports IB through distinct psychological mechanisms. These findings extend the work of Spreitzer (1995) and Miao et al. (2018) by highlighting the multidimensional nature of empowerment in knowledge-intensive work16,83.

Regarding H5a and H5b, results show that PDO significantly weakens the impact of HPWS on work meaning (β = –0.021, p < 0.05) and competence (β = –0.042, p < 0.05). This supports the view that employees in high-PDO environments tend to defer to authority, reducing their responsiveness to empowerment-oriented practices23,58. Importantly, this study contributes to cultural management literature by showing that PDO moderates specific dimensions of PE, rather than acting as a blanket suppressor.

Hypotheses H5c and H5d are rejected. Both SEM and fsQCA indicate that PDO does not significantly moderate the mediating effects of work impact and self-determination. Two explanations help contextualize these results. First, perceptions of impact tend to be shaped by hierarchical structures rather than HR practices, which may limit their responsiveness to empowerment interventions81. Second, self-determination is a fundamental requirement for IT roles, and employees may retain autonomy expectations even in high-PDO settings82,84. These findings suggest that in hierarchical cultures, HRM interventions should differentiate between psychological constructs that are structurally constrained and those open to influence.

Finally, PDO also moderates the direct relationship between HPWS and IB. The results indicate that in high-PDO settings, the effectiveness of HR practices may be reduced due to conflicting interpretations of institutional signals. This aligns with recent findings emphasizing the role of culture in shaping organizational response to HR interventions85,86.

Theoretical and empirical contributions

This study makes several theoretical contributions. First, by integrating SC, PE, and SIP theories, it presents a unified framework that explains how HPWS influence IB through cognitive and psychological mechanisms, while accounting for cultural contingencies. This advances SC theory by clarifying how institutional signals are cognitively interpreted and culturally filtered to shape employee behavior.

Second, the study deepens PE theory by treating its dimensions independently. The finding that each dimension of PE has a unique effect on IB challenges prior research that operationalized PE as a unidimensional construct16. It offers a more refined lens for future research exploring how empowerment drives innovation in complex job roles.

Third, this research extends SIP theory by demonstrating that PDO filters institutional signals unequally across different psychological dimensions. By showing that work meaning and competence are more susceptible to cultural moderation than self-determination or impact, it contributes to a more nuanced understanding of “cultural filtering” in HRM.

Fourth, the methodological combination of SEM and fsQCA addresses limitations in prior research by uncovering both linear effects and non-linear configurations. While SEM validates theoretical pathways, fsQCA highlights alternative innovation routes and the contextual logic behind them. This approach provides methodological depth and practical utility for future HRM research.

Empirically, the study offers new insights by focusing on China’s smartphone sector, which features high levels of complexity, knowledge-dependence, and innovation intensity. By targeting IT professionals, the research captures a critical yet underexplored workforce in the digital economy.

Practical implications

At the organizational level, HPWS should be implemented as an integrated and coherent system rather than a set of isolated human resource tools. In terms of fostering work meaning, managers play a crucial role as sense-makers. They should clearly articulate organizational goals, assign tasks with purpose-driven orientations, and engage employees in project initiation and reflective processes to deepen psychological investment in their work. However, the current study finds that in high power distance environments, the mediating effect of work meaning is significantly weakened. In such settings, managers are encouraged to rely on formal communication, authoritative framing, and symbolic reinforcement to strengthen employees’ identification with organizational values and reduce cultural distance.

Regarding competence, the study confirms that HPWS has a generally strong effect on enhancing employees’ perceived competence. Nonetheless, this effect appears to be partially moderated by high levels of PDO. To address this, organizations should continue investing in skill development, technical coaching, and phased feedback mechanisms. In hierarchical cultures, implementing structured training programs, tiered career development pathways, and supervisor-endorsed recognition systems can help foster a sense of security and trust among employees. These strategies make it easier for individuals to accept empowerment initiatives and recognize their own capabilities within formal authority structures.

For self-determination and work impact, the findings suggest that their mediating effects are not statistically significant in high-PDO contexts. This may be attributed to a greater reliance on managerial authority and lower expectations of autonomy among employees in hierarchical cultures. Even when organizations implement empowerment-oriented practices, employees may not fully engage due to ingrained cultural expectations. In such contexts, HRM practices should not focus solely on full-scale empowerment. A more effective strategy would be to implement progressive empowerment, starting with clear guidance and institutional authorization. Over time, organizations can gradually expand employees’ decision-making autonomy and task control to reduce cultural resistance and support psychological adaptation.

At the policy level, governments can support HPWS by aligning it with national talent development strategies. This includes training subsidies, tax incentives for R&D personnel, and support for CSR programs that strengthen career identity in the IT workforce. Promoting industry–university partnerships, such as joint labs and innovation hubs, can also boost adaptability and innovation capacity. Policymakers should incorporate HPWS principles into labor reforms by encouraging practices, such as flexible scheduling and employee participation. These initiatives will help develop a more skilled and resilient labor market, and align with national strategies like the 14th Five-Year Plan and “Made in China 2025.” They also support China’s broader goal of technological self-reliance and global competitiveness.

Limitations and future research direction

Despite its contributions, the study has certain limitations that should be addressed in future research. One limitation involves the sample and industry context. The study focused on IT employees in China’s smartphone sector, a group often overlooked in previous HRM studies. While this focus helps close an existing gap, it also narrows the generalizability of the findings. Future studies should consider broader samples that include different high-tech industries and cross-cultural settings to test the framework’s applicability.

Another limitation concerns gender distribution. The sample was predominantly male (77.96%), which may influence how generalizable the results are to more gender-balanced populations. Prior research suggests that Chinese men tend to prioritize career advancement and financial rewards, while women are more concerned with work-life balance87. These preferences may reflect broader cultural expectations, such as the traditional role of women in caregiving. To account for this, we conducted separate analyses for male and female respondents using the PLS model. The results showed that the main findings remain valid despite the imbalance. Even so, future research would benefit from more balanced or diverse samples to better capture potential gender-based variations in response to empowerment practices.

Conclusions

The study’s findings provide substantial evidence of the positive effects of HPWS on IB among IT employees in China’s smartphone industry. The strong relationships between HPWS, PE, and IB, supported by high reliability indices and validity measures, confirm the model’s robustness. Notably, PE functions as a critical mediating mechanism, with work meaning and competence showing particularly strong mediating effects in low PDO contexts. In contrast, the effects of self-determination and impact remain consistent across different cultural settings.

The broader implications suggest that organizations should prioritize the integration of HPWS with targeted empowerment strategies, while accounting for cultural differences such as power distance orientation to maximize innovation potential. These findings are consistently supported by both SEM and fsQCA analyses, which identify HPWS as a core driver of innovation and reveal multiple pathways leading to innovative behavior.

For HR practitioners and organizational leaders, these insights underscore the importance of developing psychologically empowering and culturally sensitive work environments to enhance employee innovation. This study highlights the intercon-nected relationships among HRM practices, employee empowerment, and cultural context, providing evidence-based guidance for promoting innovation within knowledge-intensive organizations.

Data availability

The data of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Muzam, J. The challenges of modern economy on the competencies of knowledge workers. J. Knowl. Econ. 14, 1635–1671 (2023).

Kraus, S., McDowell, W., Ribeiro-Soriano, D. E. & Rodríguez-García, M. The role of innovation and knowledge for entrepreneurship and regional development. Taylor & Francis 33, 175–184 (2021).

Chen, J.-X. et al. Demystifying the non-linear effect of high commitment work systems (hcws) on firms’ strategic intention of exploratory innovation: An extended resource-based view. Technovation 116, 102499 (2022).

Al-Ajlouni, M. I. Can high-performance work systems (hpws) promote organisational innovation? Employee perspective- taking, engagement and creativity in a moderated mediation model. Empl. Relat.: Int. J. 43, 373–397 (2021).

Shahzad, K., Arenius, P., Muller, A., Rasheed, M. A. & Bajwa, S. U. Unpacking the relationship between high-performance work systems and innovation performance in smes. Pers. Rev. 48, 977–1000 (2019).

Escribá-Carda, N., Balbastre-Benavent, F. & Canet-Giner, M. T. Employees’ perceptions of high-performance work systems and innovative behaviour: The role of exploratory learning. Eur. Manag. J. 35, 273–281 (2017).

Bhatti, S. H., Zakariya, R., Vrontis, D., Santoro, G. & Christofi, M. High-performance work systems, innovation and knowledge sharing: An empirical analysis in the context of project-based organizations. Empl. Relat.: Int. J. 43, 438–458 (2021).

Farrukh, M. et al. High-performance work practices do much, but hero does more: an empirical investigation of employees’ innovative behavior from the hospitality industry. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 25, 791–812 (2022).

Saleem, T., Shahab, H. & Irshad, M. High-performance work system and innovative work behavior: The mediating role of knowledge sharing and moderating role of inclusive leadership. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Aff. 8, 43–59 (2023).

Çera, E., Çera, G., Matošková, J., Ndou, V. & Gregar, A. Fostering open innovation in smes: the crucial role of high-performance working systems and the mediating influence of innovative work behaviour. J. Knowl. Manag. (2024).

Mukherjee, U. & Kaushik, D. Influence of high performance work system and personality on creativity among information technology sector. Adalya J. 8, 831–848 (2019).

Honglei, W. & Jianmin, S. The relationship between high performance work system and innovative behavior: A mediated moderation model. Sci. Sci. Manag.. (2017).

Han, J., Sun, J.-M. & Wang, H.-L. Do high performance work systems generate negative effects? How and when?. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 30, 100699 (2020).

Islam, T., Khan, M. M., Ahmed, I. & Mahmood, K. Promoting in-role and extra-role green behavior through ethical leadership: Mediating role of green hrm and moderating role of individual green values. Int. J. Manpow. 42, 1102–1123 (2021).

Bandura, A. & Cervone, D. Differential engagement of self-reactive influences in cognitive motivation. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 38, 92–113 (1986).

Spreitzer, G. M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 38, 1442–1465 (1995).

Zhang, X. & Bartol, K. M. Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity: The influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Acad. Manag. J. 53, 107–128 (2010).

Seibert, S. E., Wang, G. & Courtright, S. H. Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: A meta-analytic review. J. Appl. Psychol. 96, 981–1003 (2011).

Mirza, M. Z., Qaiser, M. I. & Memon, M. A. High-performance work systems, psychological empowerment and creative process engagement: A componential theory of creativity perspective. Creat. Innov. Manag. 33, 166–180 (2024).

Abbasi, S. G., Shabbir, M. S., Abbas, M. & Tahir, M. S. Hpws and knowledge sharing behavior: The role of psychological empowerment and organizational identification in public sector banks. J. Public Aff. 21, e2512 (2021).

Salancik, G. R. & Pfeffer, J. A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Adm. Sci. Q. 224–253 (1978).

Kirkman, B. L., Chen, G., Farh, J. L., Chen, Z. X. & Lowe, K. B. Individual power distance orientation and follower reactions to transformational leaders: A cross-level, cross-cultural examination. Acad. Manag. J. 52, 744–764 (2009).

Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values, vol. 5 (Sage, 1984).

Wang, H. & Guan, B. The positive effect of authoritarian leadership on employee performance: The moderating role of power distance. Front. Psychol. 9, 357 (2018).

Farh, J.-L., Hackett, R. D. & Liang, J. Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support–employee outcome relationships in china: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Acad. Manag. J. 50, 715–729 (2007).

Zhang, C. & Meng, J. 2024 report on the high-quality development of china’s digital economy. Tech. Rep., Academic Committee of the Digital Economy and Cybersecurity Think Tank (2024).

CCCME. Global demand remains weak, dragging down china’s mobile phone exports in 2023. Tech. Rep., China Chamber of Commerce for Import and Export of Machinery and Electronic Products (CCCME) (2024).

Cai, T. Development and future forecast of china’s mobile phone industry. In 2022 2nd International Conference on Enterprise Management and Economic Development (ICEMED 2022), 805–810 (Atlantis Press, 2022).

Wonglimpiyarat, J. Huawei smartphone business competition–fighting, surrendering, winning or losing?. Emerald Emerg. Mark. Case Stud. 13, 1–22 (2023).

Zhou, K. Z. & Li, C. B. How knowledge affects radical innovation: Knowledge base, market knowledge acquisition, and internal knowledge sharing. Strateg. Manag. J. 33, 1090–1102 (2012).

Wang, Z., Xing, L. & Zhang, Y. Do high-performance work systems harm employees’ health? An investigation of service-oriented hpws in the chinese healthcare sector. The Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 32, 2264–2297 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Liu, J., Wei, Q., Cao, Y. & Gui, S. Can hpws promote digital innovation? e-learning as mediator and supportive organisational culture as moderator. Sustainability 15, 10057 (2023).

Huang, Y., Ma, Z. & Meng, Y. High-performance work systems and employee engagement: Empirical evidence from china. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 56, 341–359 (2018).

Delery, J. E. & Doty, D. H. Modes of theorizing in strategic human resource management: Tests of universalistic, contingency, and configurational performance predictions. Acad. Manag. J. 39, 802–835 (1996).

Blau, P. Exchange and power in social life (Routledge, 2017).

Gouldner, A. W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 25, 161–178 (1960).

Kehoe, R. R. & Wright, P. M. The impact of high-performance human resource practices on employees’ attitudes and behaviors. J. Manag. 39, 366–391 (2013).

Zhai, X., Zhu, C. J. & Zhang, M. M. Mapping promoting factors and mechanisms of resilience for performance improvement: The role of strategic human resource management systems and psychological empowerment. Appl. Psychol. 72, 915–936 (2023).

Lepak, D. P., Liao, H., Chung, Y. & Harden, E. E. A conceptual review of human resource management systems in strategic human resource management research. Res. Pers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 217–271 (2006).

Agarwal, P. & Farndale, E. High-performance work systems and creativity implementation: The role of psychological capital and psychological safety. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 27, 440–458 (2017).

Chang, S., Jia, L., Takeuchi, R. & Cai, Y. Do high-commitment work systems affect creativity? a multilevel combinational approach to employee creativity. J. Appl. Psychol. 99, 665–677 (2014).

Zheng, J., Liu, H. & Zhou, J. High-performance work systems and open innovation: Moderating role of it capability. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 120, 1441–1457 (2020).

Wang, H. & Chang, Y. The influence of organizational creative climate and work motivation on employee’s creative behavior. J. Manag. Sci. 30, 51–62 (2017).

Tran Huy, P. High-performance work system and knowledge hoarding: The mediating role of competitive climate and the moderating role of high-performance work system psychological contract breach. Int. J. Manpow. 44, 77–94 (2023).

Peethambaran, M. & Naim, M. F. Unleashing the black-box between high-performance work systems and employee flourishing-at-work: an integrative review. Int. J. Organ. Analysis (2024).

Sarwar, U., Aslam, M. K., Khan, S. A. & Shenglin, S. Optimizing human resource strategies: Investigating the dynamics of high-performance practices, psychological empowerment, and responsible leadership in a moderated-mediation framework. Acta Psychol. 248, 104385 (2024).

Mehralian, G., Moradi, M. & Babapour, J. How do high-performance work systems affect innovation performance? The organizational learning perspective. Pers. Rev. 51, 2081–2102 (2022).

Yu, J., Abdul Hamid, R. & Du, L. Boundary conditions on the dark side of high-performance work systems: leader-member exchange as a job resource. Pers. Rev. (2025).

Ardianto, H. & Rosari, R. Don’t let them get stressed! hpws mechanisms in improving psychological well-being in the workplace. Int. J. Work. Heal. Manag. (2024).

Almulhim, A. F. Linking knowledge sharing to innovative work behaviour: The role of psychological empowerment. The J. Asian Finance, Econ. Bus. 7, 549–560 (2020).

Stanescu, D. F., Zbuchea, A. & Pinzaru, F. Transformational leadership and innovative work behaviour: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Kybernetes 50, 1041–1057 (2021).

Rehman, W. U. et al. High involvement hr systems and innovative work behaviour: The mediating role of psychological empowerment, and the moderating roles of manager and co-worker support. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 28, 525–535 (2019).

Al Daboub, R. S., Al-Madadha, A. & Al-Adwan, A. S. Fostering firm innovativeness: Understanding the sequential relationships between human resource practices, psychological empowerment, innovative work behavior, and firm innovative capability. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 8, 76–91 (2024).

Yang, J. & Li, X. Research on the proactive personality to the performance of deviant innovation–the mediation of innovation catalysis and the moderation of transformational leadership behavior. Forecasting 38, 17–23 (2019).

Li, G. & Yeh, Y.-H. Western cultural influence on corporate innovation: Evidence from chinese listed companies. Glob. Finance J. 55, 100810 (2023).

Xu, X., Lin, C. & Duan, L. Does hierarchical ranking matter to corporate innovation efficiency? an empirical study based on a corporate culture of seniority. Chin. Manag. Stud. 17, 594–619 (2023).

Rasiah, R. & Ren, Y. Sustainable management of a leading chinese telecommunication multinational: A case study of company x in host country malaysia. Clean. Respons. Consum. 8, 100092 (2023).

Rasheed, M. A., Mohsin, M., Farid, M. T. & Abid, M. A. Does power distance orientation really matter? A human resource flexibility–firm performance link: A moderated-mediation model. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. (2024).

Ma, X., Rui, Z. & Zhong, G. How large entrepreneurial-oriented companies breed innovation: The roles of interdepartmental collaboration and organizational culture. Chin. Manag. Stud. 17, 64–88 (2023).

Alper, S. Power distance. In Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences, 3999–4001 (Springer, 2020).

Bowling, N. A., Khazon, S., Meyer, R. D. & Burrus, C. J. Situational strength as a moderator of the relationship between job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analytic examination. J. Bus. Psychol. 30, 89–104 (2015).

Kirkman, B. L. & Shapiro, D. L. The impact of cultural values on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in self-managing work teams: The mediating role of employee resistance. Acad. Manag. J. 44, 557–569 (2001).

Ragin, C. & Fiss, P. Net effects analysis versus configurational analysis. 190–212 (2008).

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M. & Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43, 115–135 (2015).

Li, M., Zhou, Y. & Du, P. How does platform leadership improve team innovation performance? A chain mediation analysis based on SEM and fsqca. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 41, 129–139 (2024).

Jiang, T. Mediating and moderating effects in empirical studies of causal inference. China Ind. Econ. 5, 100–120 (2022).

Messersmith, J. G., Patel, P. C., Lepak, D. P. & Gould-Williams, J. S. Unlocking the blackbox: Exploring the link between high-performance work systems and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 96, 1105 (2011).

Chen, Y. & Liu, M. A study of relationship between high-performance work system and employee attitude: The mediating effect of organizational climate. In Proceedings of the 14th Interdisciplinary Management Conference (2011).

Li, C., Xiao, X., Shi, K. & Chen, X. Psychological empowerment: Measurement and its effect on employees’ work attitude in china. Acta Psychol. Sin. 38, 99 (2006).

Liu, H., Liu, S., Wang, H. & Xu, M. The influence of leader-follower value congruence in power distance on follower’s performance and its mechanism. Nankai Bus. Rev. 19, 55–65 (2016).

Chen, T., Li, F. & Leung, K. When does supervisor support encourage innovative behavior? Opposite moderating effects of general self-efficacy and internal locus of control. Pers. Psychol. 69, 123–158 (2016).

Baruch, Y. & Holtom, B. C. Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Hum. Relat. 61, 1139–1160 (2008).

Kline, R. B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling (Guilford Publications, 2023).

Thompson, B. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Understanding Concepts and Applications (Washington, DC, 2004).

Podsakoff, P. M. & Organ, D. W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 12, 531–544 (1986).

Kock, N. Common method bias in pls-sem: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. (IJEC) 11, 1–10 (2015).

Schermelleh-Engel, K., Moosbrugger, H. & Müller, H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness offit measures. Methods Psychol. Res. Online 8, 23–74 (2003).

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M. & Ringle, C. M. When to use and how to report the results of pls-sem. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31, 2–24 (2019).

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50 (1981).

Ramayah, T., Cheah, J., Chuah, F., Ting, H. & Memon, M. A. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (pls-sem) using smartpls 3.0: An updated guide and practical guide to statistical analysis. An Updat. Guid. Pract. Guid. Stat. Analysis 967–978 (2018).

Kakakhel, F. J. & Khalil, S. H. Deciphering the black box of hpws–innovation link: Modeling the mediatory role of internal social capital. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 6, 78–91 (2022).

Wu, P.-C. & Chaturvedi, S. The role of procedural justice and power distance in the relationship between high performance work systems and employee attitudes: A multilevel perspective. J. Manag. 35, 1228–1247 (2009).

Miao, Q., Newman, A., Schwarz, G. & Cooper, B. How leadership and public service motivation enhance innovative behavior. Public Adm. Rev. 78, 71–81 (2018).

Yang, J.-S. Differential moderating effects of collectivistic and power distance orientations on the effectiveness of work motivators. Manag. Decis. 58, 644–665 (2020).

Guo, Y., Zhu, Y. & Zhang, L. Inclusive leadership, leader identification and employee voice behavior: The moderating role of power distance. Curr. Psychol. 41, 1301–1310 (2022).

Adamovic, M. How does employee cultural background influence the effects of telework on job stress? the roles of power distance, individualism, and beliefs about telework. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 62, 102437 (2022).

Xian, H., Atkinson, C. & Meng-Lewis, Y. How work–life conflict affects employee outcomes of Chinese only-children academics: the moderating roles of gender and family structure. Pers. Rev. 51, 731–749 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L. drafted the main manuscript text, and R.R. provided revisions and refinements to enhance the manuscript. Both authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Universiti Malaya Research Ethics Committee under reference number UM.TNC2/UMREC_3686. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, M., Rasiah, R. High-performance work systems, psychological empowerment, and power distance orientation in shaping employee innovation, a moderated mediation model. Sci Rep 15, 27189 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08522-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08522-0