Abstract

The study attempts to establish a connection between circular economy practices and urban air pollution in the United States, utilizing panel data from fifty states from 2009 to 2022. Given the poor state of air quality and its ominous threat to public health and environmental sustainability, the present study aims to provide empirical evidence on the effectiveness of circular economy methods in reducing harmful air pollutants. Applying the GMM estimator to the regression analysis reveals a significant positive relationship between high recycling rates and reduced air pollution levels. An Environmental Kuznets Curve has also been depicted by this study—a postulation showing that although per capita income may be increasing to start with higher pollution levels, at high-income levels it could further lead to improving air quality. These findings demonstrate the significant impact of population density on pollution levels, highlighting some of the challenges faced by metropolitan regions. The article underscores the significance of incorporating circular economy approaches into urban policy frameworks and offers fresh perspectives on guiding sustainable urban development processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Air pollution remains a critical global concern, with substantial consequences for environmental health and economic stability. The persistent issues associated with air pollution are further emphasized as urbanization intensifies worldwide. Air pollution directly contributes to environmental degradation, resulting in acid rain, urban smog, and eutrophication1. In the United States, despite advancements in air quality, the ongoing presence of particulate matter (PM2.5) is a worry, especially in metropolitan regions with concentrated industrial activities and traffic emissions2. The economic consequences of air pollution are significant, impacting public health and hindering industrial productivity and growth3. Urban pollution sources, such as industrial pollutants and vehicular traffic, pose a substantial risk to public health, especially concerning respiratory and cardiovascular systems4. Moreover, air pollution exhibits a significant spatial link with the frequency of respiratory diseases, suggesting that urbanization and economic factors intensify health hazards5. Recent research highlights the serious health consequences of PM2.5 exposure, particularly the increased rates of respiratory and cardiovascular disorders that disproportionately affect at-risk populations6. Furthermore, there exists a clear association between elevated air pollution levels and the incidence of respiratory diseases, especially among at-risk groups such as the elderly and children7. The World Health Organization estimates that air pollution causes almost seven million premature deaths per year, highlighting the critical necessity for effective policy measures8. Urban regions experience considerable health repercussions due to air pollution, with notable correlations between pollution levels and respiratory and cardiovascular disorders9. With the rapid acceleration of urbanization worldwide, regulating air quality presents a growing problem, requiring concerted initiatives to alleviate the detrimental impacts of pollution on health and the environment. Demonstrate the pressing necessity for comprehensive policies and measures to mitigate the diverse effects of air pollution on public health in rapidly urbanizing areas.

Although the production of municipal solid waste (MSW) has increased worldwide, factors such as the growing population, urbanization, industrial expansion, and economic development have contributed to global economic growth and improved living standards10. Estimating worldwide garbage production at 19.8 billion tonnes in 2017,11 projected it would rise to 28 billion tonnes by 2030 and 46 billion tonnes by 2050. Excessive solid waste is a significant global environmental problem since it poses serious threats to environmental security and human health12. Recent years have seen a growing acknowledgment of the deficiencies in municipal solid waste management systems as major factors in environmental pollution and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which endanger human health and intensify global warming13. The dry recyclable elements of municipal solid waste, such as plastics, paper, cardboard, glass, textiles, and metals, remain a primary focus for sustainable waste management methods14. The manufacturing procedures for commodities like paper, glass, and aluminum are energy-intensive and frequently utilize hazardous chemicals, hence exacerbating GHG emissions15. Recent studies demonstrate that efficient recycling methods can result in large emission reductions; for example, recycling one ton of paper can markedly lower particulate matter and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions16. The global community’s intensified efforts to combat climate change necessitate the incorporation of modern waste management technologies and techniques to diminish the environmental impact of municipal solid waste17.

Research demonstrates that landfilling remains the primary method for managing municipal solid waste, as poor countries lack sufficient recycling programs18. Municipal solid waste (MSW) management is crucial, as inadequate disposal options, including landfilling and open incineration, substantially increase GHG emissions. For example, food waste in landfills produces methane (CH4), a powerful GHG that is around 25 times more effective than CO2 over a century19. The management of GHGs and air pollution is increasingly acknowledged as vital for reducing climate change, improving public health, and fostering environmental sustainability. The waste management sector significantly contributes to air pollution, with open rubbish burning resulting in considerable emissions of particulate matter and other detrimental compounds20. A reduction in the concentration of various airborne pollutants (PM, SO2, NOx, volatile organic compounds, etc.) is directly associated with a decline in GHG emissions21. Efficient waste management solutions, such as recycling and energy recovery, are essential for mitigating emissions and promoting a circular economy (CE)22. With the ongoing increase in global populations and urbanization, the necessity for sustainable waste management techniques is becoming more critical to safeguard human health and the environment23. Still, the management of municipal solid waste has global relevance. Decisions made by city and county councils, county executives, and mayors about municipal solid waste management can affect GHG emissions and support world climate change. These chemicals change weather patterns and help to cause global warming. According to recent data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the waste management sector was accountable for roughly 4% of all GHG emissions in the U.S. in 2022, or around 253 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent (MMT CO2e) out of a total of 6,343.2 MMT CO2e24. Methane is produced by anaerobic decomposition of biodegradable organic materials in the waste stream, including paper, food waste, and yard trimmings. A national and worldwide issue is the part GHGs play in driving world climate change. Different methods are being looked at to lower GHG emissions; municipal solid waste management presents notable possibilities for reductions and interactions with other industries—e.g., energy, industrial processes, forestry, and transportation—that could help lower GHG emissions even more.

CE embodies a revolutionary strategy for resource management, prioritizing efficiency, waste minimization, and ecological sustainability. This paradigm deviates from conventional linear economic processes by emphasizing closed material loops and sustainable production and consumption methods. Recent studies underscore the incorporation of CE ideas across multiple sectors, illustrating their capacity to improve resource efficiency and reduce waste. The oil and gas sector is progressively implementing circular methods to enhance sustainability and resource management, emphasizing waste reduction and by-product recovery25. The integration of digital technology in CE frameworks markedly improves resource efficiency and fosters sustainable economic growth26. As global issues like climate change and resource depletion escalate, the implementation of CE solutions is imperative for promoting sustainable development and attaining long-term environmental objectives27. Although much focus has been on how CE practices lower CO2 emissions, they also greatly influence other pollutants, including volatile organic compounds (VOCs), nitrous oxide (N2O), and CH4. CE policies, such as industrial symbiosis, reusing materials, and waste-to-energy technologies, have been shown to be successful in reducing emissions of pollutants other than CO2. Key actions include applying waste-to-energy technologies that convert waste into renewable energy, hence lowering the need for landfills and cutting GHG and methane emissions from organic waste28. Promising for reducing VOC emissions and enhancing resource use is industrial symbiosis, which entails businesses exchanging their waste and by-products with one another. While industrial symbiosis enhances resource sharing, recovering and reusing waste in waste management has greatly reduced methane emissions from landfills. While recycling and reusing materials can minimize the need for resource extraction, which usually generates VOCs and particulate matter, transforming organic waste into energy can lower methane emissions from landfills29. Moreover, creative techniques like microalgae-based wastewater treatment can generate biomass for circular uses and remove contaminants30. Innovations like the reinjection of gases into reservoirs and the recycling of waste in industrial processes have shown effective results in reducing atmospheric pollution31. By efficiently reducing non-CO2 pollutant gases, CE practices emphasize their relevance in attaining environmental sustainability and enhancing global air quality.

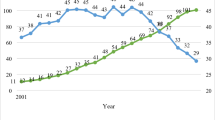

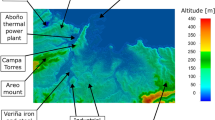

Recycling has become an essential approach for tackling environmental and health issues related to waste management. Recent studies highlight the substantial advantages of recycling, such as the mitigation of GHG emissions and the preservation of natural resources. Recycling procedures can result in considerable energy savings, as the manufacture of recycled materials requires much less energy than that of virgin materials32. Furthermore, efficient recycling procedures not only reduce trash but also augment economic prospects by generating employment and supplying businesses with essential raw materials33. The incorporation of sophisticated technologies in recycling, including automated sorting systems, has demonstrated enhanced efficiency and elevated recycling rates, hence advancing sustainable waste management34. Nonetheless, obstacles persist, such as elevated operational expenses and the necessity for enhanced infrastructure, which may impede recycling initiatives35. Confronting these obstacles is crucial for optimizing the environmental and economic advantages of recycling within a CE paradigm. While Tennessee, Louisiana, and West Virginia show the lowest rates, Maine, Vermont, and Massachusetts are shown in Fig. 1 as the top performers among U.S. states. The levels of air pollution in several states are shown in Fig. 2. While New Hampshire, Wyoming, and Hawaii show the least, California, Arizona, and Nevada show the most.

When considered together, industrialization, urban expansion, and growing energy demands are driving states increasingly to face the deterioration of air quality. These changes have caused urban environmental damage and health issues. Although interest in the CE as a sustainable urban development strategy is growing, the empirical research linking CE practices to urban air pollution—particularly in the United States—remains scant and scattered. Although earlier studies, such as those by36, examined how CE ideas could help states become more resilient to pollution from various sources, and31 proposed models that integrate environmental and economic elements to reduce emissions, research on the impact of CE on urban air quality remains insufficient. Dincă et al.37 applied econometric tools to identify efficient CE policies, and38 examined waste systems using system dynamics. Conversely, these studies are limited in scope, lack pollutant-specific insights, or do not use sophisticated econometric techniques appropriate for causal inference in panel data settings. This paper adds several fresh contributions to the body of work: First, it offers a thorough empirical framework connecting urban air pollution in U.S. states to circular economy practices—especially municipal solid waste recycling. This paper systematically investigates the intersection of CE and air quality, unlike current studies that treat them as separate domains (e.g.,39), and emphasizes how CE practices can simultaneously address concerns of atmospheric pollution and waste management. Second, the study broadens the analytical spectrum beyond CO2, often the only focus in environmental policy studies. By adding more air quality indicators—particulate matter (PM10) and nitrogen oxides (NOx)—the study provides a more thorough assessment of CE’s environmental performance and catches the several facets of urban air pollution. Third, it employs sophisticated econometric methods, particularly the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) estimator in a dynamic panel data environment. Unlike conventional static models, this approach makes it easier to draw obvious cause-and-effect conclusions by addressing concealed variations and the concurrent interaction between pollution results and recycling activities. Fourth, drawing on data from U.S. states helps to balance both unchanging and evolving concealed elements that might influence the relationship between air quality and CE policies. This approach greatly increases the internal validity of the study and offers more consistent policy-relevant data. Fifth, the study provides direct policy consequences by means of its results on the CE practices most effectively lowering certain pollutants. Urban planners developing integrated sustainability plans meant to minimize waste and control air pollution must have this knowledge since it will help them to improve environmental outcomes and public health. The article is structured as follows: Section “Literature review” reviews the relevant literature; Section “Methodology” outlines the approach; Section “Results and discussion” presents the empirical results; and Section “Robustness analysis” concludes with policy recommendations and avenues for further research.

Literature review

Waste management is acknowledged as a critical environmental and socioeconomic issue in the United States, garnering the focus of policymakers and scholars in recent decades. This matter has acquired significant relevance because of the historical and legal advancements associated with it, notably the enactment of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) in 1976. This legislation facilitated the closure of open dumps and mandated regional waste management planning, progressively shifting the responsibility for trash management to municipalities40. The development and execution of effective policies in this domain are essential for mitigating environmental damage, promoting public health, and increasing resource efficiency. Policies aimed at reducing food waste and managing electronic waste explicitly mitigate the economic and societal consequences linked to waste41. Trash legislation in the United States, especially concerning pay-as-you-throw (PAYT) programs and extended producer responsibility (EPR), is essential for rectifying deficiencies in trash management systems. PAYT regulations impose fees on households according to their trash production, hence promoting waste minimization and recycling efforts. Research demonstrates that towns implementing PAYT have experienced considerable decreases in trash discharge and enhancements in recycling rates. Folz et al.42 and Huang et al.43 conducted a national survey revealing that cities implementing PAYT rules experienced significant reductions in waste per home, hence illustrating its efficacy in fostering sustainable waste management practices. Furthermore, EPR reallocates the obligation of waste management from municipalities to producers, motivating them to design products with end-of-life factors in consideration. This method may result in less waste production and enhanced recycling rates. The studies by44 and45 demonstrated that EPR can substantially reduce the financial strain on local governments while fostering a circular economy. By thoroughly interacting with current U.S. waste legislation, one can formulate more effective waste management plans adapted to local circumstances, hence improving the sustainability of waste management systems.

A notable U.S.-based trash policy is the advancement of recycling activities. These projects seek to improve recycling rates and diminish landfill waste, which is essential for sustainable waste management. Diverse state and local regulations have been enacted to promote recycling. Massachusetts has implemented a comprehensive solid waste master plan that establishes statewide recycling objectives and promotes municipal governments to provide complementary measures. Studies demonstrate that initiatives like curbside recycling programs and local government funding substantially impact recycling activities46. The efficacy of recycling projects may differ according to the particular policies used. Research indicates that the presence of recycling facilities and curbside collection significantly enhances recycling rates. Moreover, the enforced segregation of recyclables has been shown to convert non-recyclers into engaged contributors to recycling initiatives47. Notwithstanding advancements, the U.S. continues to encounter obstacles in realizing its national recycling rate objectives. A substantial deficiency exists due to the absence of a comprehensive national recycling statute, and financial support for recycling infrastructure is insufficient. Mitigating these issues via legislative reform and augmented funding could improve the efficacy of recycling projects48. Recycling activities in the United States are essential for trash management; nevertheless, their efficacy depends on supportive regulations and sufficient funding. The implementation of community-based waste management policy (CBWMP) emphasizes the involvement of local communities in trash management initiatives to foster cleaner and healthier ecosystems. These regulations underscore the significance of community involvement in garbage management. By engaging locals in decision-making and promoting local initiatives, communities can customize waste management systems to meet their individual requirements. The study by49 demonstrated that active community involvement enhances trash management efficacy by cultivating a sense of ownership and accountability among residents. Community-oriented strategies can markedly enhance public health and environmental standards. By including social justice elements and leveraging technology, these policies can tackle waste management issues while fostering sustainable practices. The results indicate that a comprehensive approach including all stakeholders is crucial for attaining long-term sustainability in waste management49. The ramifications of CBWMP underscore the necessity for enabling structures that enable local communities. Policymakers are urged to create initiatives that enhance community engagement, supply educational materials, and foster collaboration among diverse stakeholders. This methodology can result in more robust waste management systems that are better prepared to address local difficulties50. These policies provide a crucial method for improving waste management efficiency in the U.S. By promoting community involvement and cooperation, these strategies can enhance environmental and public health results. In conclusion, due to current issues and the necessity for enhanced infrastructure and regulations, waste management policies in the United States are progressing towards more sustainable and economically feasible strategies51.

Recent studies have concentrated on the influence of recycling on urban air pollution, emphasizing its capacity to alleviate environmental problems and enhance public health. Komilova et al.52 examined the relationship between air pollution and public health, demonstrating that mitigating pollutants by recycling and other sustainable activities can result in decreased incidences of respiratory and cardiovascular disorders. Yang et al.53 examined the correlation between public environmental concern and urban air pollution, demonstrating that heightened public engagement in environmental activities can result in substantial decreases in air pollution levels. This highlights the imperative of enacting policies that incorporate recycling to enhance air quality. Razzaq et al.54 examined the short- and long-term effects of recycling municipal solid trash on environmental and economic metrics at the national level in the United States. They focused on analyzing the relationships and interactions among these components. Their studies indicated that an increase in recycling rates positively affects both economic conditions and environmental quality. Tomić et al.55 conducted comparative assessments that validated the substantial economic value generated by recycling, with its contribution to environmental sustainability. Akomolafe et al.4 underscored the significance of recycling and sustainable practices in mitigating carbon emissions from urban pollution sources. Effective recycling programs can enhance air quality by reducing waste and encouraging the utilization of renewable resources. Xiao et al.56 similarly found that the recovery of municipal solid waste may transform carbon emission sources into renewable energy, thereby significantly reducing overall carbon emissions. Kumar et al.57 have shown that the incorporation of green areas and recycling programs within green–blue-grey infrastructure (GBGI) can markedly diminish air pollution levels. The research indicated that GBGI can reduce many pollutants, implying that repurposing materials for urban green initiatives can improve air quality. A study in Shiraz, Iran, revealed that elevating recycling rates from 15 to 80% might substantially decrease air pollutants, with projections indicating a reduction of up to 3.43 million tons of emissions alone from recycling paper and glass58. Maury-Ramírez et al.59 highlighted the possibility of recycling in the development of air-purifying and self-cleaning building materials. These ideas can mitigate urban air pollution by employing recycled materials in construction. Furthermore,60 demonstrated that the use of circular economy principles, especially in urban mining pilot towns in China, has yielded encouraging outcomes in enhancing waste management efficiency and diminishing pollution levels. The Urban Mining Pilot Policy (UMPP) has enabled the recycling of urban trash, enhancing environmental quality and resource conservation. This method not only tackles trash management issues but also significantly mitigates air pollution in metropolitan environments. Hossain et al.61 assert that municipal solid waste is a significant contributor to air pollution in Dhaka City. The concentration of contaminants in landfills exceeds that of secondary transfer stations and open-air disposal sites. The potential toxicity of PM2.5 in landfills is shown to be double that at secondary transfer locations. The findings underscored the necessity for improved designs of waste treatment facilities to safeguard human health. Kumar et al.62 posited that inadequate waste treatment in several Indian states is exacerbating environmental health risks for the populace. Inadequate waste management from families and poor coordination by municipal and state agencies during trash disposal promote pathogenic proliferation, ultimately jeopardizing public health. Insufficient waste management infrastructure and inadequate source waste segregation predominantly affect peri-urban regions, leading to the disposal of mixed refuse in landfills. The significance of community involvement in recycling initiatives and environmental legislation designed to enhance air quality.

Recent studies demonstrate that recycling is essential for mitigating urban air pollution via processes such as trash reduction, enhancement of public health, and the establishment of sustainable infrastructure. The incorporation of recycling into urban planning and community behaviors is vital for attaining cleaner air and healthier urban environments. Nonetheless, despite extensive literature highlighting the environmental advantages of recycling, a comprehensive understanding of its effects on urban air pollution levels across various metropolitan contexts remains inadequately explored. Current studies typically examine recycling and pollution reduction in isolation from the broader impacts of circular economy strategies that integrate waste management with social and economic considerations. This research seeks to address a gap in the literature by undertaking a comprehensive analysis of the relationship between circular economy initiatives and urban air pollution in U.S. states from 2009 to 2022. This study will employ advanced statistical techniques, notably the Generalized Method of Moments estimator, to demonstrate the direct impact of improved recycling rates and circular economy initiatives on air quality indicators such as PM10, NOx, and CO2 concentrations. The study will investigate the impact of socioeconomic factors, including income levels and population density, on recycling dynamics and pollution. This study links circular economy techniques to urban air quality management, improving comprehension of how integrated methods might address air pollution in urban settings and assisting policymakers and urban planners in fostering sustainable urban growth.

Methodology

This analysis is based on a panel data series for 50 states in the United States from 2009 to 2022. The study focuses on the states that passed through a set of strict exclusion criteria concerning data availability, permitting one to draw valid conclusions. The appendix provides detailed information about the studied states. Table 1 provides descriptions of the variables.

To explore the relationship between circular economy and air pollution, the study employs regression models, expressed in the following Eq. (1):

\(\text{Circular Economy}\) (\({\alpha }_{1}\)) reflects activities such as recycling, waste reduction, and material reuse. Its existence is due to an increased concern for the sustainable use of resources to prevent environmental degradation. However, theoretically, the impact of recycling on air pollution remains uncertain in terms of its magnitude. Recycling primarily reduces air pollution by reducing the demand for raw material extraction and waste burning through incineration. Empirical evidence from Shiraz, presented by58, manifests that increased recycling rates can lead to significant reductions in air pollutant emissions. Further, studies by63 and64 point to the pollution-decreasing benefits of recycling industrial waste products. On the other hand, inadequately regulated recycling activities can themselves be polluting. Milojević et al.65 note that recycling electric vehicles releases harmful substances, particularly when plants lack the capability to recycle batteries and electronic devices in a safe manner. Similarly,66 and other authors alert that decomposition of organic waste during recycling yields GHGs and toxic chemicals. Thus, the aggregate effect of circular economy activities on air pollution depends on the circumstances and is a function of the quality of regulations, technology, and waste composition.

\(Income Per Capita\) (\({\alpha }_{2}\)) is introduced to capture the effect of economic growth on environmental quality. The literature presents conflicting evidence regarding its effect. According to the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis, some people believe that the relationship between economic growth and pollution is not straightforward: when a country is at a low-income level, economic growth tends to increase pollution because of more industrial activity and energy use, but when a country reaches a high-income level, it leads to cleaner technologies and stricter environmental rules, which help reduce pollution. For example,67 and68 find that an increase in per capita income by 1% is associated with a decrease of 2.88–4.54% of air pollution for emerging economies. Khaliq et al.69 examined the validity of EKC theory in South Asian nations, revealing that CO₂ emissions first rise with economic expansion but then decline after attaining a specific income threshold. Khaliq et al.70 affirmed the existence of an inverted U-shaped correlation between economic growth and CO₂ emissions in BRICS-T nations.

Conversely, other studies reveal a positive association between pollution and income. Setiawan et al.71 suggest that rising per capita income in Indonesia’s Java Island is linked to worsening air conditions primarily due to more industrial and transportation activities. Wang et al.72 also argue that inequality in the income of residents of high-income regions may perpetuate the scale of pollution inasmuch as distributional features of income do matter. Accordingly, the income per capita coefficient will either be positive or negative based on policy setting and the level of development.

\(\text{Income Per Capita Square}\) (\({\alpha }_{3}\)) is added as a way to account for nonlinear effects of income in reducing air pollution. This allows for the empirical testing of the EKC hypothesis by ascertaining whether or not there is a turning point after which rising income erases environmental degradation. Theoretically, a positive income per capita coefficient and a negative coefficient on its square would indicate an inverted U relationship. Empirical research verifies this specification. Başar et al.73 and Lieu et al.74 illustrate that as economic growth advances, pollution actually rises initially but eventually diminishes as countries become richer and invest in environmental improvements. Gdad et al.75 also note equivalent patterns in different nations that indicate income per capita squared plays a significant role in describing alterations in air quality, especially when environmental policy and take-up improve with increased incomes.

Lastly, \(Population Density\) (\({\alpha }_{4}\)) is a measure of urbanization that has effects on pollution in different channels, including transport behavior, energy consumption, and industrial concentration. Its predicted sign is also unknown. Higher population density can intensify pollution through greater mobility and infrastructure demands, as exemplified by76, who document the correlation between vehicle numbers and pollution in high-density urban areas. Similarly,77 demonstrate that in Norway, rising population density increases concentrations of NO2 and particulate matter. Other studies indicate that compact urban form can be an agent of pollution reduction. Yang et al.78 believe that urban agglomeration will shift economic activity to the tertiary sector, which is typically cleaner. Castells-Quintana et al.79 state that highly populated states actually contain lower per capita CO2 and PM2.5 emissions simply because they possess more efficient transport networks and infrastructure. These inconsistent findings suggest that the relationship between population density and air pollution is conditioned by factors such as the quality of urban planning, availability of public transport, and sectoral composition of economic activity.

The literature on panel data analysis indicates possible endogeneity concerns stemming from the characteristics of the data utilized in this study. The research follows the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) estimation approach for the successful tackling of these issues. The estimated results and theoretical interpretations could be very different from what they really mean, and the coefficient signs could be off because of endogeneity bias80. Endogeneity may originate from several sources, although there are recognized techniques to alleviate it.

The GMM method is very beneficial for examining dynamic endogeneity bias in panel datasets, unlike two-stage least squares (2SLS) and three-stage least squares (3SLS), which are mostly utilized for cross-sectional data. Originally developed by81 and further enhanced by82, GMM provides a robust way of working with dynamic panel data characterized by sedentary causal relationships. Wintoki et al.83 say that the GMM model can properly handle a lot of endogeneity issues, including heterogeneity that can’t be seen, simultaneity, and issues caused by dynamic endogeneity. This approach addresses endogeneity by internally changing the data via a statistical method that deducts current variable values from their historical equivalents. This approach successfully mitigates endogeneity concerns84. This internal modification may decrease the number of observations; however, it paradoxically improves the efficiency of GMM calculations85. This work uses advanced econometric methodologies to elucidate the intricate links between material recycling and road transport infrastructure while maintaining the accuracy and dependability of the findings.

Results and discussion

This section, using the works by86 and87, initially examines the possible existence of cross-sectional dependence (CSD). Secondly, we performed unit root tests accounting for cross-sectional dependence. Third, we assessed slope heterogeneity. Fourth, we conducted cointegration tests to ascertain whether the variables exhibit a long-term association. After conducting the causality tests, we present the model estimation. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for the study’s primary variables—air pollution, circular economy practices, income per capita, income per capita squared, and population density—illustrating their variance and magnitude throughout the 50 U.S. states from 2009 to 2022. Table 2 displays the descriptive statistics for the variables incorporated in this study.

The results of the correlation test are presented in Table 3. Table 4 presents the findings of the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) test. In multiple regression analysis, VIF test is a crucial diagnostic instrument for assessing the presence and degree of multicollinearity among independent variables. Estimates of regression coefficients become unstable and unreliable when numerous variables in a model demonstrate significant correlation, a phenomenon referred to as multicollinearity88. The VIF test findings indicate the absence of multicollinearity in the research models of this study.

Accurate estimates of the mutual relationships of the model variables depend on first evaluations of their fundamental traits. Evaluating cross-sectional independence is absolutely crucial since ignoring it could lead to skewed results in empirical research. When two or more groups share unobserved traits, cross-sectional dependence can occur; if not addressed, it can reduce the usefulness of panel data techniques89. Thus, eliminating skewed estimates depends much on cross-sectional dependence. Encompassing all variables investigated in this article, Table 5 shows the results of several tests run on the equation. The tests comprise the Pesaran-scaled LM and Pesaran CD tests introduced by90 as well as the Breusch-Pagan LM test created by91. The findings show that every test fails the null hypothesis of cross-sectional independence.

The following concern relates to the unit root test. The LLC test by92 and the IPS test by93 do not account for cross-sectional dependency. We employed the cross-sectionally integrated panel series (CIPS) and CADF tests, which are effective with limited sample numbers, to accurately assess the integration features of the series under consideration while accounting for cross-sectional dependence. The test results in Table 6 indicate that all variables in the model adhere to either an I(0) or I(1) process. This finding indicates that all series are stationary at their levels or first differences.

In panel data analysis, it is crucial to determine the equivalence of the slope coefficients. Two techniques were utilized to address this issue:94 and95. This study aimed to assess the null hypothesis of slope homogeneity against the alternative hypothesis of heterogeneity. The results demonstrated variability in the slope coefficients; hence, they rejected the null hypothesis. Consequently, we can utilize econometric heterogeneous panel methods. Table 7 presents the results of the heterogeneity tests for slopes.

After conducting diagnostic studies, including unit root tests, CSD, and slope heterogeneity evaluation, it is essential to determine the presence of a long-term relationship among the variables. The Westerlund cointegration method was employed to address this significant issue, a sophisticated technique acknowledged for detecting cointegration in panel data settings, despite cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity. The results shown in Table 8 confirm the presence of a long-term relationship.

We evaluate the causal links among our variables by pairwise Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels96. The results of this study are presented in Table 9. Our data reveal a bidirectional causal link between historical ideals of the circular economy and air pollution, suggesting an endogeneity issue. This finding further validates the utilization of our dynamic techniques. All variables, with the exception of population density, have a direct causal relationship with air pollution.

We utilize the two-step system GMM estimator to mitigate potential endogeneity and dynamic panel bias. This methodology employs lagged levels and differences of explanatory variables as instruments, enhancing efficiency compared to difference GMM. To verify the validity of our instruments and model specification, we perform the Arellano-Bond tests for autocorrelation and the Hansen J test for overidentifying limitations. The AR(2) test indicates no second-order serial correlation (p = 0.342), and the Hansen test affirms instrument validity (p = 0.215), suggesting that our dynamic panel model is appropriately defined. In light of the pronounced cross-sectional dependence and heterogeneity shown in Tables 5 and 7, we augment our two-step GMM estimation using Common Correlated Effects (CCE) estimators and fixed effects models utilizing Driscoll–Kraay standard errors. These methods explicitly tackle spatial and common-factor dependence, thus ensuring robust inference. Table 10 illustrates that the computed coefficients across these alternative parameters maintain consistent signs and significance, so strengthening the robustness of our findings concerning the influence of circular economy practices on air pollution. In the empirical models, air pollution is designated as the dependent variable, quantified by the PM2.5 emission index. A significant disparity exists in the amount of the circular economy coefficient between the two-step system GMM (− 0.008) and fixed effects (− 0.421) calculations. This gap mostly occurs because the GMM estimator addresses potential endogeneity, dynamic panel bias, and measurement error through the use of internal instruments, resulting in more cautious and consistent estimates. The fixed effects estimator, although it accounts for unobserved time-invariant heterogeneity, fails to completely resolve endogeneity, which may lead to an overestimation of the coefficient due to omitted variable bias or reverse causation.

Regression analysis indicated a significant negative relationship between air pollution levels in U.S. states and circular economy practices. Different basic approaches could clarify this connection. By supporting the best use of resources, the circular economy improves resource efficiency, so reducing waste and lowering the need for new material extraction. Being among the major contributors of pollutants, industrial operations experience a great reduction because of these efficiencies97. It also includes creative waste management ideas, mostly stressing improving composting and recycling. Improving garbage management plans that prevent landfills helps municipalities to reduce general air pollution since they are major sources of methane and other pollutants37. The move to renewable energy sources is another key circle of circular economy activity. Many of these projects encourage the use and harnessing of renewable energy sources in place of depending on fossil fuels for power generation. It then contributes notably to the lowering of carbon emissions, among other harmful air pollutants released into the environment98. Ultimately, efficient policy and community involvement will determine the success of circular economy initiatives. Informed communities about sustainable practices show notable behavioral changes that help to lower pollution. Policies encouraging a culture of sustainability ensure greater adherence to the values of the circular economy and involvement60. With its interconnected systems, the circular economy offers a strong way to lower urban air pollution, therefore stressing the possible environmental advantages and guaranteeing sustainable living in states. In their research on circular economy practices in European nations,37 discovered that effective execution might greatly lower air pollution via renewable energy and public awareness initiatives. These outcomes correspond to their results.60 underline the ability of circular economy rules to foster pollution decrease, particularly in Chinese urban areas. Hodgkinson et al.99 claim that the circular economy idea is linked to a decrease in undesirable environmental effects such as air pollution.

The model suggested a positive link between air pollution and income per capita as well as a negative effect of the square of income per capita on the air pollution in US states. That said, this dynamic is typical of the upside-down-U relationship, known as EKC, whereby money causes pollution to spread until a particular threshold level, after which it starts to de-escalate with the increasing of income. Income’s good impact suggests that more income per capita corresponds with more consumption and energy use, which would generate more emissions and pollution. Conversely, the negative impact of the square of income per capita indicates that higher income means more resource allocation toward cleaner technology and control, therefore reducing pollution. This outcome supported100. This intricate interplay reveals most clearly the delicate links between economic development and environmental degradation and, therefore, advocates for sustainable development policy.

In U.S. states, the model shows a positive link between population density and degrees of air pollution. Many interrelated causes exist for this. First, more people means more polluters. Along with more energy use, there is usually a notable rise in motor vehicle and industrial activity in densely populated areas. Such activity results in higher pollution emissions, mostly ruled by NO2 and different kinds of particulate matter (PM)101. Furthermore, the metropolitan shape and infrastructure of densely populated areas significantly contribute to the aggravation of air quality issues. Higher building densities in these states often mean less green space, which can trap toxins and disrupt airflow, therefore raising pollution levels102. Transportation dynamics also come into play; areas with high population density tend to rely on personal means of transportation. Traffic congestion resulting from this could cause more emissions from transportation103. Moreover, the interplay of these elements with other socioeconomic ones aggravates the link with pollution even more. The socioeconomic dynamics, such as industrial activities and energy consumption patterns, may greatly influence pollution levels in urban areas, adding another layer of complexity to the relationship between population density and air pollution76. By finding that urbanization and the particular qualities of emission sources resulting from density directly relate to higher NO2 and PM10 levels in China,101 back these findings. Liang et al.102 went on to show that air quality is greatly affected by population density, particularly in medium- to high-elevation states. By claiming that very urbanized states greatly add to air pollution problems,103 found a clear link between rising population density and air pollution levels in Turkey.

Robustness analysis

In order to evaluate the robustness of the results, we re-estimate the models utilizing alternative measures of air pollution, specifically PM10, NOx, and CO2, as dependent variables. Each robustness check replaces PM2.5 with one of the alternative pollutants to assess whether the fundamental relationships remain consistent across various specifications of air pollution.

Results, as shown in Table 11, report regression results that were obtained using the GMM estimator, preserving the significance of our previous evidence and the considerable influence of circular economy measures in reducing air pollution. Negative recycling coefficients for all three pollutants’ cases—PM10, NOx, and CO2—indicate a strong negative relationship between recycling activity and the amount of pollutants. One unit of recycling is estimated to decrease PM10 by 0.003, NOx by 0.007, and CO2 by 0.004. The findings indicate that enhancing recycling activities could significantly contribute to reducing emissions. To address concerns about causal inference and potential reverse causality, we conducted panel Granger causality tests using the Dumitrescu–Hurlin methodology, which accommodates heterogeneity among states. The results demonstrate bidirectional causality: recycling activity Granger causality suggests that reductions in air pollution result in improved air quality, thereby promoting more recycling behaviors. This confirms the presence of feedback effects and mitigates concerns about reverse causality. Consequently, this substantiates the advocacy for stringent recycling policies to get optimal environmental advantages.

Conversely, the positive per capita income coefficients show causality from higher per capita income to higher NOx and CO2 emissions with coefficients 0.150 and 0.111, respectively. Using the squared term, however, will reverse this direction. The negative values of the income per capita squared (-0.078 for PM10 and -0.067 for CO2) point toward the existence of EKC. This describes the fact that while economic development in terms of wealth may initially imply development of pollution levels, there exists a point beyond which additional economic growth leads to decreasing pollution as funds are invested into cleaner technology and stricter environmental policies. Effectively, even while the more affluent urban communities would initially create more emissions, the scope for investment in abatement techniques is found to be apparent with rising incomes.

The positive population density coefficients of 0.129 for PM10, 0.116 for NOx, and 0.181 for CO2 show that population density increases with increasing pollution levels. The findings point out the difficulty in states being able to supply clean air since high numbers of pollution sources like car traffic and industrialization are more common in more densely populated states. As urbanization continues to extend its reach, the supply of better air quality will become increasingly important. Current studies provide further insight into the nexus between circular economy practice and air pollution. Dincă et al.37 examined the influence of circular economy practices on the air quality of 28 European nations for the period 2011–2019 based on practices such as renewable energy use, public awareness, and good policy interventions in mitigating air pollution. Adambekova et al.31 concentrated on the oil and gas sector of Kazakhstan, finding that circular economy activity led to a 2.2 times reduction of air pollution, indicating the tremendous reduction potential of emissions through new practices and green investments. Kobylynska et al.104 made a comparison of CO2 emissions across various regions in Ukraine and discovered that there is a high correlation between the adoption of circular economy measures and reduced emissions, and regions characterized by higher population density are associated with cleaner technology.

Moreover105 examined the complex interconnections among green space, economic development, and circular economy hazards in 31 European nations for the period 2009–2020. They established that increased municipal waste generation is linked with increased GHG and NOx emissions, but restricting them using circular economy instruments can reduce waste and emissions. Mongo et al.106 examined the impact of these practices on EU-15 CO2 emissions over the period 2000–2015 and concluded that while there was efficiency in emissions reduction in the short term, circular economy practices in the long term can have counterintuitive consequences, highlighting the necessary balance of resource efficiency with sufficiency. Last but not least36, ascertained the contribution of circular economy practices in urban areas towards achieving cleaner air and air pollution resilience building in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Zhu et al.107 showed that circular economy practice-based pilot states achieved a decrease of 2.92 percentage points in pollutant emissions, further validating the effectiveness of such interventions in air quality improvement.

Conclusions and policy recommendations

This study offers substantial empirical evidence regarding the impact of circular economy practices on reducing urban air pollution across 50 U.S. states from 2009 to 2022. The results indicate that improved recycling initiatives markedly decrease PM₂.₅ concentrations, and a bidirectional causality is present between air pollution and the adoption of a circular economy. A 10-percentage-point rise in recycling rates correlates with an estimated 0.08 µg/m3 decrease in PM2.5 concentrations—an effect having significant ramifications for public health and environmental policy. The findings substantiate the circular economy’s feasibility as a strategic policy tool for enhancing air quality in urban environments. In addition to recycling, fundamental circular principles such as resource efficiency, the adoption of renewable energy, and waste reduction provide systemic avenues for achieving environmental sustainability. The EKC indicates that economic growth may initially raise pollution levels, but ultimately results in environmental enhancements as income and regulatory ability improve. The correlation between population density and pollution highlights the necessity for urban strategies that focus on spatial planning and emission-heavy activities.

Policy implications encompass the adoption of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) frameworks to internalize environmental costs across the product lifecycle and encourage eco-design. Incorporating circular economy ideas at the design and manufacturing stages—where the majority of environmental consequences are established—can significantly diminish upstream emissions. Fiscal mechanisms, like tax incentives for sustainable technologies and investments in recycling infrastructure, can expedite this transformation. Ultimately, integrating circularity into urban planning—via compact city design, green infrastructure, and low-emission transportation systems—will facilitate enduring enhancements in air quality. This research importantly recognizes potential issues of endogeneity and reverse causality. Granger causality tests indicate mutual feedback between recycling and air quality, whereas sensitivity studies employing alternative pollutants (PM₁₀, NOₓ, and CO₂) validate the robustness of the findings. The incorporation of controls for regulatory rigor and industry composition enhances the inference. Policymakers require a balanced array of interventions: short-term benefits from enhancing recycling rates must be paired with long-term measures aimed at systemic transformation. Collaborative governance, public participation, and dependable environmental monitoring systems are essential for effective execution. Investing in circular supply chains and urban sustainability projects can facilitate cities’ transition to cleaner, more resilient futures. Future research should investigate the varied effects of circular economy policies in many metropolitan settings and examine how socio-economic and institutional factors influence their efficacy. Comparative evaluations among jurisdictions with differing levels of circular economy adoption might provide useful insights into scalable and context-specific methods for mitigating urban air pollution.

Data availability

Data are publicly available and they can be accessed at the links provided in Table 1 and all data are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Mostafanezhad, M., Vaddhanaphuti, C. & Evrard, O. Making air pollution legible: Environmental‐health data and the naturalization of the smoky season in Northern Thailand. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. (2024).

Tu, H. The Impact of industrial emissions on outdoor air pollution in different U.S. cities from 1980 to 2024. Environ. Clim. Prot. https://doi.org/10.23977/envcp.2024.030106 (2024).

Hu, Y., Shen, Y., Zhou, J. & Gong, J. Air pollution and urban economic growth: A study based on dynamic models. Global Nest J. 26(9) (2024).

Akomolafe, O. O. et al. Air quality and public health: A review of urban pollution sources and mitigation measures. Eng. Sci. Technol. J. 5(2), 259–271 (2024).

Ye, Y., Tao, Q. & Wei, H. Public health impacts of air pollution from the spatiotemporal heterogeneity perspective: 31 provinces and municipalities in China from 2013 to 2020. Front. Public Health 12, 1422505 (2024).

Alves Laucas e Myrrha, L. H. et al. Health and economic benefits of accelerating the PM 10 interim targets in brazil’s new air quality resolution: A case study in southern brazil. Atmosphere 16(3), 270 (2025).

Castaman, G. Epidemiological study on the impact of urban air pollution on residents’ respiratory health. Life Stud. 1(2), 83–98 (2025).

Abid, A., Shabbir, M. A., Mubeen, H., Javed, K. & Shabbir, I. A call to action for global solutions to air quality crisis: Urgent actions and innovative solutions needed. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 75(1), 1–2 (2025).

Iram, S. et al. Impact of air pollution and smog on human health in Pakistan: A systematic review. Environments 12(2), 46 (2025).

Norouzian Baghani, A. et al. Characterization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons associated with PM10 emitted from the largest composting facility in the Middle East. Toxin Rev. 40(4), 1481–1495 (2021).

Maalouf, A. & Mavropoulos, A. Re-assessing global municipal solid waste generation. Waste Manag. Res. 41(4), 936–947. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X221074116 (2023).

Kaza, S., Shrikanth, S. & Chaudhary, S. More Growth, Less Garbage (World Bank, 2021).

Yang, G. et al. A review on the evaluation models and impact factors of greenhouse gas emissions from municipal solid waste management processes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 31(19), 27531–27553 (2024).

Khanal, B. & Maharjan, K. K. Estimation of Greenhouse gas emission from municipal solid waste management techniques-A case of Rampur Municipality, Palpa District, Nepal. J. Environ. Sci. 10, 34–45 (2024).

Ivanova, Y., Zhuzhgov, A. & Isupova, L. Synthesis of aluminum-copper catalysts based on product of centrifugal thermal activation of gibbsite and their activity in selective oxidation of ammonia. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 162, 112287 (2024).

Agyeman, E., Quansah, D. A., Ntiamoah, A., Mensah, L. D. & Ramde, E. W. Toward a circular economy in Ghana’s renewable energy sector: A quantitative assessment of waste from solar photovoltaic modules in Ghana. Int. J. Green Energy https://doi.org/10.1080/15435075.2025.246913 (2025).

Dubsok, A., Limphitakphong, N., Sugsaisakon, S. & Kittipongvises, S. Greenhouse gases emissions and factors influencing sustainable solid waste management based on the circular economy indicators: The city case in Thailand. In E3S Web of Conferences vol. 566, 02004 (EDP Sciences, 2024).

Golbaz, S., Mahvi, A. H., Emamjomeh, M. M. & Baghani, A. N. Formulating landfill gas emissions model for forecasting methane generation from waste under Iranian scenario. Int. J. Environ. Waste Manage. 28(3), 298–316 (2021).

Meegoda, J. N., Chande, C. & Bakshi, I. Biodigesters for sustainable food waste management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 22(3), 382 (2025).

Jadidi, M. A. & Ghassani, G. A. Waste 2 wealth non-hazardous waste recycling approaches in oil and gas fields. In SPE Conference at Oman Petroleum & Energy Show, Muscat, Oman, SPE-224973-MS. https://doi.org/10.2118/224973-MS (2025).

Jailaybekov, Y. A., Berkinbayev, G. D., Yakovleva, N. A. & Askarov, S. A. Influence of the motor transport emissions on the atmospheric air quality in the city of Almaty and ways of the problem’solution. Sustain. Technol. Green Econ. 2(1), 24–32 (2022).

Lombardi, L. & Castaldi, M. J. Energy recovery from residual municipal solid waste: State of the art and perspectives within the challenge to climate change. Energies 17(2), 395 (2024).

Mohajan, H. K. Waste management strategy to save environment and improve safety of humanity. Front. Manag. Sci. 4(2), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.56397/fms.2025.03.05 (2025).

EPA. Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions In U.S. (2025).

Adebayo, Y. A., Ikevuje, A. H., Kwakye, J. M. & Esiri, A. E. Circular economy practices in the oil and gas industry: A business perspective on sustainable resource management. GSC Adv. Res. Rev. 20(3), 267–285 (2024).

Williams, J., Prawiyogi, A. G., Rodriguez, M. & Kovac, I. Enhancing circular economy with digital technologies: A pls-sem approach. Int. Trans. Educ. Technol. (ITEE) 2(2), 140–151 (2024).

Wang, Y., He, Y. & Gao, X. Synergizing renewable energy and circular economy strategies: Pioneering pathways to environmental sustainability. Sustainability 17(5), 1801 (2025).

Somadayo, S., Wardani, E. Y., Razi, T. K., WP, A. G. & Agung, T. S. Innovative waste-to-energy solutions: Assessing the potential of circular economy models for sustainable waste management. Global Int. J. Innov. Res. https://doi.org/10.59613/global.v2i11.351 (2024).

Grobelak, A. et al. Environmental impacts and contaminants management in sewage sludge-to-energy and fertilizer technologies: Current trends and future directions. Energies 17(19), 4983. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17194983 (2024).

Bhatt, P., Bhandari, G., Bhatt, K. & Simsek, H. Microalgae-based removal of pollutants from wastewaters: Occurrence, toxicity and circular economy. Chemosphere 306, 135576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.135576 (2022).

Adambekova, A. et al. Reducing atmospheric pollution as the basis of a regional circular economy: Evidence from Kazakhstan. Sustainability 17(5), 2249. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052249 (2025).

Ait-Touchente, Z., Khellaf, M., Raffin, G., Lebaz, N. & Elaissari, A. Recent advances in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) recycling. Polym. Adv. Technol. 35(1), e6228 (2024).

Guo, F. et al. Synergistic reduction of pollutants and GHGs in China’s PET industry: A material metabolism perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 218, 108260 (2025).

Ahmed, M. I. B. et al. Deep learning approach to recyclable products classification: Towards sustainable waste management. Sustainability 15(14), 11138 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Municipal solid waste management challenges in developing regions: A comprehensive review and future perspectives for Asia and Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 930, 172794 (2024).

Khajuria, A. & Verma, P. Circular economy for “blue skies” in building resilient cities—towards the UN 2030 Agenda for sustainable development goals. Front. Sustain. 6, 1479452. https://doi.org/10.3389/frsus.2025.1479452 (2025).

Dincă, G., Milan, A. A., Andronic, M. L., Pasztori, A. M. & Dincă, D. Does circular economy contribute to smart cities’ sustainable development?. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(13), 7627 (2022).

Kristianto, A. H., Suratman, E., Yani, A. & Dewata, I. Integrating circular economies: Enhancing border regions environment and public health. Econ. Dev. Anal. J. 13, 3. https://doi.org/10.15294/edaj.v13i3.8202 (2024).

Lakatos, E. S. et al. Conceptualizing core aspects on circular economy in cities. Sustainability 13(14), 7549. https://doi.org/10.3390/SU13147549 (2021).

Louis, G. E. A historical context of municipal solid waste management in the United States. Waste Manag. Res. 22(4), 306–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X04045425 (2004).

Evans, A. I. & Nagele, R. M. A lot to digest: Advancing food waste policy in the United States. Nat. Resour. J. 58(1), 177–214. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4898164 (2018).

Folz, D. H. & Giles, J. N. Municipal experience with “pay-as-you-throw” policies: Findings from a national survey. State Local Gov. Rev. 34(2), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160323X0203400203 (2002).

Huang, J. C., Halstead, J. M. & Saunders, S. B. Managing municipal solid waste with unit-based pricing: Policy effects and responsiveness to pricing. Land Econ. 87(4), 645–660. https://doi.org/10.3368/le.87.4.645 (2011).

Leclerc, S. H. & Badami, M. G. Extended producer responsibility for E-waste management: Policy drivers and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 251, 119657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119657 (2020).

Chaudhary, N. Extended producer responsibility (EPR) in Nepal: A transformative policy strategy for sustainable waste management. Tribhuvan Univ. J. 39(2), 188–204. https://doi.org/10.3126/tuj.v39i2.72999 (2024).

Callan, S. J. & Thomas, J. M. The impact of state and local policies on the recycling effort. East. Econ. J. 23(4), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315240091-20 (1997).

Viscusi, W. K., Huber, J. & Bell, J. Alternative policies to increase recycling of plastic water bottles in the United States. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy https://doi.org/10.1093/reep/res006 (2012).

Saragih, A., Janjevic, M. & Winkenbach, M. Revitalizing municipal solid waste recycling: Review of current US policies and potential directions for the circular economy. https://doi.org/10.38105/spr.5rbiekp17o(2024).

Musiana, M., Ishak, S. N., Soamole, M. S. & Surasno, D. M. Analysis of community-based waste management policies to achieve clean and healthy environment. West Sci. Interdiscip. Stud 2(04), 749–753. https://doi.org/10.58812/wsis.v2i04.784 (2024).

Beccarello, M. & Di Foggia, G. Sustainable development goals data-driven local policy: Focus on SDG 11 and SDG 12. Adm. Sci. 12(4), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12040167 (2022).

Almansour, M. & Akrami, M. An environmental assessment of municipal solid waste management strategies in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A comparative life cycle analysis. Sustainability 16(20), 9111 (2024).

Komilova, N., Egamkulov, K., Hamroyev, M., Khalilova, K. & Zaynutdinova, D. A. The impact of urban air pollution on human health. Meдичнi пepcпeктиви= Medicni perspektivi (Medical perspectives) 3, 170–179 (2023).

Yang, J., Yin, W. & Jin, Y. Analyzing public environmental concerns at the threshold to reduce urban air pollution. Sustainability 15(21), 15420. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115420 (2023).

Razzaq, A., Sharif, A., Najmi, A., Tseng, M. L. & Lim, M. K. Dynamic and causality interrelationships from municipal solid waste recycling to economic growth, carbon emissions and energy efficiency using a novel bootstrapping autoregressive distributed lag. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 166, 105372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105372 (2021).

Tomić, T., Kremer, I. & Schneider, D. R. Economic efficiency of resource recovery—analysis of time-dependent changes on sustainability perception of waste management scenarios. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-192887/v1 (2022).

Xiao, W., Liu, T. & Tong, X. Assessing the carbon reduction potential of municipal solid waste management transition: Effects of incineration, technology and sorting in Chinese cities. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 188, 106713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2022.106713 (2023).

Kumar, P. et al. Air pollution abatement from Green-Blue-Grey infrastructure. Innov. Geosci. 2(4), 100100 (2024).

Farzadkia, M. et al. Municipal solid waste recycling: Impacts on energy savings and air pollution. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 71(6), 737–753 (2021).

Maury-Ramírez, A., Rinke, M. & Blom, J. Low-carbon embodied, self-cleaning, and air-purifying building envelope components using TiO2 photocatalysis, 3D printing, and recycling. Coatings 14(9), 1228 (2024).

Shen, H. & Liu, Y. Can circular economy legislation promote pollution reduction? Evidence from urban mining pilot cities in China. Sustainability 14(22), 14700 (2022).

Hossain, M. A. et al. Emission of particulate and gaseous air pollutants from municipal solid waste in Dhaka City, Bangladesh. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 26(1), 552–561 (2024).

Kumar, G., Vyas, S., Sharma, S. N. & Dehalwar, K. Challenges of environmental health in waste management for peri-urban areas. In Solid Waste Management: Advances and Trends to Tackle the SDGs 149–168 (Springer, 2024).

Mohsenzadeh, F., Nouri, J., Ranjbar, A., Fazli, M. M. & Babaie, A. A. Air pollution control through kiln recycling by-pass dust in a cement factory. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 3(1), 5–8 (2006).

Temitayo, O., Jacob, S. & James, O. Investigation of Co and So2 from acid clay treatment of used lubricating oil. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering vol. 413, 012052 (IOP Publishing, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/413/1/012052

Milojević, S., Miletic, I., Stojanovic, B., Milojević, I. & Miletić, M. Logistics of electric drive motor vehicles recycling. Mobil. Veh. Mech. 46(2), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.24874/mvm.2020.46.02.03 (2020).

Zimoglyad, A. D., Klimanov, T. V. & Terlyga, N. S. Organic waste as a renewable energy source. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering Vol. 1079, 072031 (IOP Publishing, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/1079/7/072031

Iqbal, N., Khan, A., Gill, A. & Abbas, Q. Nexus between sustainable entrepreneurship and environmental pollution: Evidence from developing economy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-09642-y (2020).

Sun, H., Pofoura, A. K., Mensah, I. A., Li, L. & Mohsin, M. The role of environmental entrepreneurship for sustainable development: Evidence from 35 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 741, 140132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140132 (2020).

Khaliq, A. & Mamkhezri, J. Asymmetrical analysis of economic complexity and economic freedom on environment in South Asia: A NARDL approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30(38), 89049–89070 (2023).

Khaliq, A., Atique, A., Hina, H. & Bilal, A. Impact of electricity generation, consumption, energy trade, and ICT on the environment in Pakistan: A NARDL and ARDL analysis. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World 31(3), 279–297 (2024).

Setiawan, H. A., Lutfi, M. & Rahmayani, D. Determinant factors of air quality: Empirical study in Java Island. J. REP (Riset Ekonomi Pembangunan) 7(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.31002/rep.v7i1.24 (2022).

Wang, F., Yang, J., Shackman, J. & Liu, X. Impact of income inequality on urban air quality: A game theoretical and empirical study in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18(16), 8546. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18168546 (2021).

Başar, S. & Tosun, B. Environmental pollution index and economic growth: Evidence from OECD countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28(27), 36870–36879. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-13225-w (2021).

Lieu, P. T. & Ngoc, B. H. The relationship between economic diversification and carbon emissions in developing countries. Int. J. Appl. Econ. Financ. Account. 15(1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.33094/ijaefa.v15i1.747 (2023).

Gdad, M. M. & Kademani, M. S. The economic growth and environmental kuznets curve hypothesis evolution and assessment, causes and prospective: A review of literature under a critical analysis. Int. J. Sci. Res. Eng. Manag. https://doi.org/10.55041/ijsrem37226 (2024).

Zhan, D., Kwan, M. P., Zhang, W., Wang, S. & Yu, J. Spatiotemporal variations and driving factors of air pollution in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14(12), 1538. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121538 (2017).

Zhivkov, P. & Kesarovski, T. Dynamic relationship between population densities and air quality in the four largest norwegian cities. In 2024 19th Conference on Computer Science and Intelligence Systems (FedCSIS) 713–718 (IEEE, 2024). https://doi.org/10.15439/2024F838

Yang, B., Ding, L. & Tian, Y. The influence of population agglomeration on air pollution: An empirical study based on the mediating effect model. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science Vol. 687, 012014 (IOP Publishing, 2021). https://doi.org/10.1088/1755-1315/687/1/012014

Castells-Quintana, D., Dienesch, E. & Krause, M. Density, cities and air pollution: a global view. Available at SSRN 3713325. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3713325 (2020).

Ullah, A., Pinglu, C., Ullah, S. & Hashmi, S. H. The dynamic impact of financial, technological, and natural resources on sustainable development in Belt and Road countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29(3), 4616–4631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-15900-4 (2022).

Arellano, M. A. N. U. E. L. & Bond, S. T. E. P. H. E. N. Application to Employment Equations (1991).

Blundell, R. & Bond, S. Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J. Econom. 87(1), 115–143 (1998).

Wintoki, M. B., Linck, J. S. & Netter, J. M. Endogeneity and the dynamics of internal corporate governance. J. Financ. Econ. 105(3), 581–606 (2012).

Roodman, D. How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. Stand. Genomic Sci. 9(1), 86–136 (2009).

Wooldridge, J. M. C. Introductory econometrics: A modern approach (5th ed.) (Boston, 2012).

Mamkhezri, J. Assessing price elasticity in US residential electricity consumption: A comparison of monthly and annual data with recession implications. Energy Policy 200, 114537 (2025).

Khaliq, A. & Mamkhezri, J. The impact of renewable portfolio standards and land-use governance on CO2 and gross total emissions in four US regions. Appl. Energy 372, 123832 (2024).

Salmerón, R., García, C. B. & García, J. Variance inflation factor and condition number in multiple linear regression. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 88(12), 2365–2384. https://doi.org/10.1080/00949655.2018.1463376 (2018).

Phillips, P. C. & Sul, D. Dynamic panel estimation and homogeneity testing under cross section dependence. Economet. J. 6(1), 217–259 (2003).

Pesaran, M. H. General diagnostic tests for cross section dependence in panels. institute for the study of labor (IZA). IZA Discussion Paper. No. 1240 (2004).

Breusch, T. S. & Pagan, A. R. The lagrange multiplier test and its applications to model specification in econometrics. Rev. Econ. Stud. 47(1), 239–253 (1980).

Levin, A., Lin, C.-F. & Chu, C.-S.J. Unit root tests in panel data: Asymptotic and finitesample properties. J. Econom. 108(1), 1–24 (2002).

Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H. & Shin, Y. Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J. Econom. 115(1), 53–74 (2003).

Pesaran, M. H. & Yamagata, T. Testing slope homogeneity in large panels. J. Econom. 142(1), 50–93 (2008).

Blomquist, J. & Westerlund, J. Testing slope homogeneity in large panels with serial correlation. Econ. Lett. 121(3), 374–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2013.09.012 (2013).

Dumitrescu, E.-I. & Hurlin, C. Testing for granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Econ. Modell. 29(4), 1450–1460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2012.02.014 (2012).

Muñoz, E. & Navia, R. Circular economy in urban systems: How to measure the impact?. Waste Manag. Res. 39, 197–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X21989173 (2021).

Stanković, J. J., Janković-Milić, V., Marjanović, I. & Janjić, J. An integrated approach of PCA and PROMETHEE in spatial assessment of circular economy indicators. Waste Manag. 128, 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2021.04.057 (2021).

Hodgkinson, I., Maletz, R., Simon, F. G. & Dornack, C. Mini-review of waste-to-energy related air pollution and their limit value regulations in an international comparison. Waste Manag. Res. 40(7), 849–858 (2022).

Caron, J. & Fally, T. Per capita income, consumption patterns, and CO2 emissions. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 9(2), 235–271. https://doi.org/10.1086/716727 (2022).

Baek, J. I. & Ban, Y. U. The impacts of urban air pollution emission density on air pollutant concentration based on a panel model. Sustainability 12(20), 8401. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208401 (2020).

Liang, Z. et al. The context-dependent effect of urban form on air pollution: A panel data analysis. Remote Sens. 12(11), 1793. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12111793 (2020).

Kaplan, G., Avdan, Z. Y. & Avdan, U. Spaceborne nitrogen dioxide observations from the Sentinel-5P TROPOMI over Turkey. In International Electronic Conference on Remote Sensing 4 (MDPI, 2019). https://doi.org/10.3390/ECRS-3-06181

Kobylynska, T., Hrynchak, N. & Motuzka, O. The impact of the circular economy on mitigating the consequences of climate change in the regions of Ukraine. Econ. Innov. Econ. Res. J. 12(3), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.2478/eoik-2024-0037 (2024).

Apostu, S. A., Gigauri, I., Panait, M. & Martín-Cervantes, P. A. Is Europe on the way to sustainable development? Compatibility of green environment, economic growth, and circular economy issues. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20(2), 1078. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021078 (2023).

Mongo, M., Laforest, V., Belaïd, F. & Tanguy, A. Assessment of the impact of the circular economy on CO2 emissions in Europe. J. Innov. Econ. Manag. 39(3), 15–43. https://doi.org/10.3917/jie.pr1.0107 (2022).

Zhu, Y., Mao, C., Jia, Q., Barnes, S. J. & Yao, Q. Building better cities: Evaluating the effect of circular economy city construction on air quality via a quasi-natural experiment. J. Environ. Public Health 2022(1), 3151072. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/3151072 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.E.M.: Conceptualization; Formal Analysis; A.K.: Data curation; Resources; Software: A.R.M.E.: Conceptualization; Validation; Writing initial draft; M.R.: Investigation; Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 12.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Esmaeilpour Moghadam, H., Karami, A., Moghadam Ebrahimabad, A.R. et al. The impact of circular economy initiatives on urban air quality in the United States. Sci Rep 15, 23860 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08554-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08554-6