Abstract

Population aging has become a global phenomenon with significant implications for public health. Aging accelerates the development of age-related diseases, leading to increased social and economic burdens. Obesity further exacerbates these effects by increasing the risk of comorbidities and reducing life expectancy. This study examines the relationships between various anthropometric indices—A Body Shape Index (ABSI), Body Roundness Index (BRI), Body Mass Index (BMI), and Conicity Index (C-index)—and biological age acceleration, providing insights into the effectiveness of these indices in predicting biological aging. Data were sourced from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2009–2018, involving 22,921 participants after exclusions. Biological aging acceleration was assessed using Phenotypic Age Acceleration (PhenoAgeAccel) and Klemera-Doubal Method Age Acceleration (KDM-AA) algorithms. Associations between anthropometric indices and biological aging acceleration were evaluated using weighted multiple linear and logistic regression models, adjusted for potential confounders. Restricted Cubic Spline (RCS) regression explored non-linear associations. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis assessed the predictive capabilities of the anthropometric indices. Higher values of all four anthropometric indices (ABSI, BRI, BMI, and C-index) were significantly associated with increased biological aging acceleration (both PhenoAgeAccel and KDM-AA), even after adjusting for covariates. Significant non-linear relationships were observed in all four anthropometric indices. Subgroup analyses revealed robust associations across various demographics and health conditions. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) showed that the C-index exhibited the highest predictive capability for biological age acceleration. This study reveals significant associations between higher anthropometric indices and biological age acceleration in American adults, with the C-index being the most effective predictor.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Population aging has emerged as a global phenomenon. According to a 2019 United Nations report, 9% of the world’s population is currently 65 years or older, with this percentage expected to rise to 16% by 20501. Aging accelerates the development and onset of various age-related diseases, resulting in significant social and economic costs2,3. Despite the inevitability of aging, there is often a discrepancy between chronological age and the rate of aging4. Hence, biological age was proposed to assess the aging condition of the human body. Biological age is inferred from the developmental state of normal human physiology and anatomy, indicating the actual condition of the body’s tissue structure and physiological functions. It offers a more accurate reflection of the body’s aging process compared to chronological age (CA)5. Biological age acceleration is calculated by subtracting chronological age from biological age, reflecting how quickly an individual’s physiological aging occurs compared to their actual age. When this difference is positive, it implies accelerated aging, potentially increasing susceptibility to age-associated diseases and conditions.

The detrimental effects of aging are further exacerbated by obesity, which is characterized by the excessive accumulation of adipose tissue within the body. Approximately 36.5% of the adult population in the United States is considered obese, and 42.8% of individuals aged 60 and older are obese6. Even worse, it is estimated that at least 2.8 million people worldwide die each year due to complications related to obesity in worldwide7. Obesity is associated with decreased life expectancy due to a significantly increased risk of comorbidities8,9,10. Additionally, obesity accelerates the onset of age-related diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders8,11,12. Therefore, managing obesity is crucial in mitigating the health impacts of an aging population.

Obesity is typically assessed using various anthropometric indices, which are both cost-effective and non-invasive. The most widely used measure is the Body Mass Index (BMI), calculated as weight divided by the square of height (kg/m2). BMI is commonly employed in clinical and epidemiological studies to define obesity and overweight13 and is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). However, BMI has limitations; it cannot differentiate between muscle mass and fat mass, which can lead to the misclassification of muscular individuals as overweight or obese14. Additionally, BMI only accounts for weight and height, ignoring fat distribution in the body, and does not distinguish between central and peripheral fat15,16. To address these limitations, other anthropometric indices have been developed, such as A Body Shape Index (ABSI), Body Roundness Index (BRI), and the Conicity Index (C-index). ABSI was empirically derived by adjusting waist circumference (WC) for height and weight, serving as a measure of relative waist size compared to individuals with the same weight and height17. It has been validated as a robust predictor of mortality risk in various observational studies18,19. Similarly, the BRI, proposed by Thomas et al. in 2013, combines height and WC to describe a person’s body shape, offering a better reflection of body fat and visceral fat proportions than traditional indices like BMI, WC, and hip circumference20. The C-index assumes that individuals with more abdominal fat are biconical, while those with less are cylindrical, aiming to identify abdominal obesity using body mass, height, and WC measurements21,22. Studies have demonstrated the C-index’s effectiveness in distinguishing underlying abdominal obesity23,24 and its status as an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality in older adults without cancer25.

In this study, we utilized data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2009–2018 and explore the association between various anthropometric indices and biological age acceleration. We hypothesized that novel anthropometric indices (ABSI, BRI, and C-index) would exhibit a stronger association with biological age acceleration than BMI. To evaluate this hypothesis, we assessed the effectiveness of these anthropometric indices in predicting biological age acceleration by examining the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC).

Materials and methods

Study population

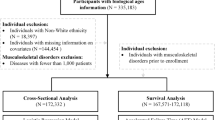

The NHANES is a detailed series of cross-sectional studies targeting the non-institutionalized civilian population in the United States (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/). This survey gathers a broad spectrum of information, including demographic, socioeconomic, dietary, and health-related data. These data are collected through in-person interviews, physical and physiological assessments, and comprehensive laboratory tests. We selected five consecutive NHANES cycles from 2009 to 2018 (2009–2010, 2011–2012, 2013–2014, 2015–2016, and 2017–2018) because they represent the most recent 10-year span of data available, ensuring both a sufficiently large sample size and methodological consistency. This period provides a comprehensive dataset that includes all relevant variables necessary to examine the associations of interest in our study. A total of 49,693 participants completed the survey. We excluded 8040 participants due to missing data on WC, height, weight, or BMI. Additionally, 18,319 participants lacking data on biological age [Phenotypic age (PhenoAge) and Klemera–Doubal Method biological age (KDM-BA)] were also excluded. These two biological age measures are not provided as direct variables in the NHANES databases; rather, we derived them from the available NHANES biomarker data using established formulas. After further excluding pregnant women and individuals under 20 years old, the final sample consisted of 22,921 individuals (Fig. 1).

Data collection

Exposure variable

WC was measured in centimeters by placing a flexible tape around the uppermost lateral border of the ilium while the participant was standing. Weight was measured in kilograms (to the nearest tenth), and height was measured in centimeters (to the nearest tenth). BMI was then calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). The specific mathematical formulas for calculating ABSI, BRI, and the Conicity Index are as follows:

For ABSI, waist circumference was measured in centimeters, BMI was calculated as weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of height (in meters), and height was recorded in meters.

For BRI, both waist circumference and height should be measured in the same unit, typically centimeters, to ensure consistency in the calculation.

For the C-index, waist circumference was measured in meters, weight in kilograms, and height in meters.

For variables transformed to z-scores, we computed

where X is the raw value, μ is the sample mean, and σ is the sample standard deviation of X in the analytic cohort. Odds ratios are therefore interpretable per one-SD increase in the original metric.

Outcome variable

The BioAge R package has developed and validated multiple algorithms for calculating biological aging using NHANES data (http://github.com/dayoonkwon/BioAge)27. In this study, two methods were used to evaluate biological age: PhenoAge and KDM-BA. PhenoAge is generated from an algorithm that estimates mortality risk based on biomarkers, providing a detailed assessment of an individual’s aging rate and their likelihood of developing age-related diseases. KDM-BA uses regression analysis of aging-related biomarkers against chronological age to gain insights into health status and risks for age-related conditions. A higher KDM-BA suggests a greater vulnerability to age-related diseases, while a lower KDM-BA indicates healthier aging.

This study used biological markers such as systolic blood pressure, blood creatinine, urea nitrogen, albumin, total cholesterol, glycated hemoglobin, lymphocyte percentage, mean erythrocyte volume, leukocyte count, and alkaline phosphatase to evaluate the aging phenotype. These markers are available in the NHANES datasets from 2009 to 2018.

To measure the rate of aging, Phenotypic Age Acceleration (PhenoAgeAccel) and KDM Age Acceleration (KDM-AA) were calculated as indicators of accelerated biological aging. PhenoAgeAccel is the residual obtained from regressing PhenoAge on chronological age, while KDM-AA is the residual from regressing KDM-BA on chronological age. A positive residual signifies accelerated aging, whereas a negative residual indicates decelerated aging.

Assessment of covariates

Covariate data were collected through surveys, physical examinations, and laboratory tests. The surveys provided information on participants’ age, sex, ethnicity, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, caloric intake, and health conditions such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. Physical assessments included measurements such as blood pressure.

Ethnicity was categorized into four groups: Mexican American, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and other. Education levels were classified into three categories: below high school, high school graduates, and above high school education. Alcohol consumption was categorized into three groups: never (fewer than 12 drinks in a lifetime), low-to-moderate (up to one drink per day for women and up to two drinks per day for men in the past year), and high (more than one drink per day for women and more than two drinks per day for men in the past year). Smoking status was divided into three categories: never (fewer than 100 cigarettes in a lifetime), former (more than 100 cigarettes in a lifetime but not currently smoking), and current (more than 100 cigarettes in a lifetime and currently smoking).

Cardiovascular disease (CVD), hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), and cancer were treated as dichotomous variables (with or without disease). CVD was diagnosed based on a history of congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, angina, or myocardial infarction. Hypertension was defined by any of the following criteria: systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, a medical diagnosis of high blood pressure, or the use of blood pressure-lowering medications. Diabetes mellitus (DM) was diagnosed based on a previous diagnosis, diabetes medication or insulin use, fasting blood sugar ≥ 126 mg/dL, glucose levels ≥ 200 mg/dL after oral glucose intake, or HbA1c levels ≥ 6.5%. Cancer data were collected through self-reported information obtained during survey interviews, where participants were asked whether they had ever been diagnosed with specific types of cancer by a healthcare provider. Additionally, cancer history was further validated through medical record reviews when available.

Average daily energy intake was assessed over a 2-day period using data from a food consumption survey. The unit of measurement for caloric intake was kilocalories (kcal). Physical activity levels were quantified by assigning a metabolic equivalent (MET) value based on the compendium of activity energy costs for each activity listed in the questionnaire. The Poverty Income Ratio (PIR) is calculated by dividing a household’s total income by the federal poverty threshold for its size and composition. This ratio is used to assess participants’ relative economic status, with lower values indicating poverty and higher values indicating greater income relative to the poverty line. Detailed methodologies are available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses followed the CDC’s guidelines for NHANES data, applying the MEC exam weight (WTMEC2YR) to account for the complex survey design, including stratification, clustering, and unequal probabilities of selection. Participants’ baseline characteristics were categorized by PhenoAgeAccel tertiles. Continuous variables were presented as either adjusted means ± standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges, depending on their distribution.

Continuous variables with approximately normal distributions were summarized as survey-weighted means with standard deviations, while non-normally distributed variables were presented as medians with interquartile ranges, based on the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and visual inspection of histograms. Categorical variables were reported as unweighted counts and survey-weighted percentages. All descriptive statistics accounted for the NHANES complex sampling design through the application of sampling weights. Group comparisons were conducted using survey-weighted statistical methods, including Rao-Scott adjusted chi-square tests for categorical variables and survey-weighted one-way ANOVA with design-based Wald F-tests (Ra-Scott F-tests) for comparisons of weighted means of continuous variables.

Weighted multiple linear regression was utilized to estimate regression coefficients (β) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for anthropometric indices in relation to PhenoAgeAccel and KDM-AA across three statistical models. In both the logistic regression and ROC analyses, PhenoAgeAccel and KDM-AA were used as binary outcomes, defined by values greater than zero to indicate accelerated aging. Both continuous variables and categorical variables (divided into quartiles) were analyzed using linear regression and logistic regression models. Model 1 included no confounders. Model 2 adjusted for age, sex, and ethnicity. Model 3 further adjusted for lifestyle factors such as alcohol consumption, smoking status, dietary caloric intake, physical activity and medical history (CVD, hypertension, diabetes, and cancer) (see Supplementary Methods for model equations and covariates). For logistic regression models, ABSI and C-index were standardized using z-score transformation. This standardization allows for interpretation of odds ratios per one standard deviation increase, facilitating comparison across variables with different measurement scales. As a sensitivity check, BMI and BRI were also standardized in identical fashion (see Supplementary Table S4), and yielded effect estimates consistent with those from the original-unit models. In contrast, linear regression models were conducted using variables in their original units to retain interpretability in the context of continuous aging outcomes.

Restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression was performed within survey-weighted logistic models using the untransformed anthropometric indices, with four knots placed at the 5th, 35th, 65th, and 95th percentiles of each variable, to characterize potential non-linear associations with PhenoAgeAccel and KDM-AA. Subgroup and interaction analyses were subsequently performed in survey-weighted linear regression models to assess effect modification by key demographic, health-related, and lifestyle factors. The participants were assigned to the following categories: Age: Participants were divided into two groups: those under 60 years and those 60 years or older. Medical History: Participants with and without hypertension, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease (CVD) were grouped accordingly. Lifestyle Factors: Participants were categorized based on their physical activity levels and dietary energy intake. Physical activity was classified into three levels based on the total metabolic equivalent (MET) hours per week: Low: < 600 MET-min/week; Moderate: 600–3999 MET-min/week; High: ≥ 4000 MET-min/week. Dietary caloric intake was divided into tertiles, based on the distribution of caloric intake in the sample. ROC curve analysis was used to evaluate the ability of each anthropometric measure to identify PhenoAgeAccel. All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 4.2.2 (https://www.R-project.org; R Foundation, Austria) (see Supplementary Methods for the list of R packages used). A p-value of less than 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Participant characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the 22,921 participants, divided into three tertiles based on PhenoAgeAccel, reveal significant disparities in health, socio-economic status, and body composition indices (Table 1). Participants in Tertile 3 are generally older (48.46 years old), predominantly male (63.9%), and have higher rates of cardiovascular disease (12.8%), hypertension (42.6%), and diabetes (25.8%). This group also exhibits poorer socio-economic indicators, such as lower poverty income ratios (median 2.55) and lower education levels (39.4% high school, 55.5% more than high school). It is worth noting that their various anthropometric indices higher values, with BMI of 31.50 kg/m2, BRI of 5.81, and C-index of 1.34.

In contrast, Tertile 1 includes participants who are relatively younger (48.43 years), fewer males (32.5%), and have lower incidences of cardiovascular disease (4.8%), hypertension (24.0%), and diabetes (6.3%). They also show better socio-economic conditions, with higher poverty income ratios (median 3.43) and higher education levels (26.0% high school, 68.9% more than high school). Their anthropometric indices are lower, with BMI of 27.02 kg/m2, BRI of 4.48, and C-index of 1.29. These differences highlight that higher phenotypic age acceleration is associated with adverse health outcomes, lower socio-economic status, and higher anthropometric indices.

Among the total sample of 22,921 participants, 6407 (28.0%) had a PhenoAgeAccel greater than zero, and 7566 (33.0%) had a KDM-AA greater than zero, indicating evidence of accelerated biological aging. The weighted descriptive statistics of the two aging acceleration indicators, PhenoAgeAccel and KDM-AA, provide additional insights into the biological aging status of the study population (Table S1). The weighted mean ± standard error of PhenoAgeAccel was − 2.56 ± 0.08, with a median of − 2.90 and an interquartile range (IQR) from − 5.53 to 0.05. Similarly, the weighted mean ± standard error of KDM-AA was − 2.46 ± 0.08, with a median of –2.80 and an IQR ranging from − 7.16 to 1.71. These results suggest that, on average, participants experienced a deceleration in biological aging relative to their chronological age; however, the wide distribution reflects considerable inter-individual variability in aging trajectories.

Relationship between anthropometric indices and biological age acceleration

There are significant positive associations between higher values of anthropometric indices and PhenoAgeAccel, and these associations persist after adjusting for various covariates (Table 2). For ABSI, the continuous variable showed a robust association in Model 3 (β = 53.31, 95% CI 40.40–66.21, p < 0.001), and categorical analysis indicated that the highest Quartiles (Q4) show increasing associations with PhenoAgeAccel. Similarly, BRI, BMI, and the C-index displayed substantial positive continuous associations with PhenoAgeAccel, with β values of 0.15, 0.60, and 9.26 respectively, all p < 0.001. Categorical analyses for these indices consistently indicated significant trends (p for trend < 0.001) of increasing PhenoAgeAccel across higher quartiles, especially in the fourth quartile, which demonstrated the most substantial increases across all models. R2 values for all linear models were added to Tables 2 and S2.

Next, we used PhenoAgeAccel greater than zero as a binary outcome variable and employed logistic regression (Table 3). PhenoAgeAccel greater than zero indicates that an individual’s biological age is older than their chronological age, suggesting an accelerated aging process. The logistic regression analysis shows that higher values of anthropometric indices, including ABSI, BRI, BMI, and the C index, are significantly associated with an increased risk of an accelerated aging process. Furthermore, the relationship between anthropometric indices and KDM-AA, another biological age acceleration calculation method, was also investigated, revealing robust positive associations between higher values of anthropometric indices and increased KDM-AA (Tables S1–2). Nagelkerke pseudo-R2 values were added to Tables 3 and S3. These findings suggest that individuals with higher measures of body shape and size experience greater biological aging acceleration.

Restricted cubic spline regression analysis

The analyses of the RCS results demonstrate significant non-linear relationships between anthropometric indices and PhenoAgeAccel, which suggests that the increase in OR is not uniform across all anthropometric indices (Fig. 2). For ABSI and C-index the p-values for both overall and non-linear effects are less than 0.0001, indicating strong statistical significance. These indices show that as their values increase, the OR for PhenoAgeAccel greater than zero increases markedly, particularly beyond certain thresholds (0.08 for ABSI and 1.2 for C index). Similarly, BMI and BRI also show significant associations with aging outcomes, with overall p-values less than 0.0001 and non-linear p-values of 0.0001 and 0.0307, respectively. Higher BMI and BRI values are associated with increased ORs, highlighting the heightened risk of accelerated aging process as these indices rise. As a sensitivity analysis, we re‐fit all four RCS models using z-score-standardized indices (Fig. S2). The curves exhibit virtually identical shapes, inflection points, and significance levels, confirming the robustness of our results. Similarly, significant non-linear relationships between anthropometric indices and KDM-BA were observed (Fig. S1).

The restricted cubic spline regression between anthropometric indices and PhenoAgeAccel. The dose–response relationship was evaluated using restricted cubic spline regression for the ABSI (a), BRI (b), BMI (c), and C-index (d) and PhenoAgeAccel with covariates adjusted as in model 3. The odds ratio is represented by the red line and the 95% confidence interval is shown in pink. ABSI A Body Shape Index, BRI Body Roundness Index, BMI Body mass index, C-index Conicity Index.

Subgroup analysis and interaction analyses

The subgroup analyses revealed that the association between ABSI and PhenoAgeAccel remained significant when the group was divided by age, hypertension, diabetes, CVD history, different levels of dietary energy intake, and different levels of physical activity (Fig. 3). However, the association was not significant in the Black race subgroup. Similarly, the associations between BRI, BMI, and C-index and PhenoAgeAccel were generally robust across various subgroups (Figs. 4, 5, 6).

Additionally, significant interactive effects were noted across age, race, hypertension, diabetes, CVD history, dietary energy intake, and physical activity levels in the ABSI-PhenoAgeAccel association (p for interaction < 0.05). The BRI analysis also demonstrated significant interactive effects for age, race, hypertension, diabetes, and physical activity levels (p for interaction < 0.05). For BMI, significant interactions were observed with age, race, hypertension, diabetes, dietary energy intake, and physical activity levels (p for interaction < 0.05). In the C-index analysis, significant interactive effects were found for age, race, hypertension, diabetes, dietary energy intake, and physical activity levels (p for interaction < 0.05). In summary, the subgroup analyses highlight the significant and varying impacts of four anthropometric indices on health outcomes across different populations.

ROC analyses

Figure 7 presents the weighted ROC curves for the four anthropometric indices in predicting elevated PhenoAgeAccel. Among them, the C-index demonstrated the highest discriminatory performance, with an AUC of 0.633 (95% CI 0.624–0.641), followed by BMI [AUC 0.620 (95% CI 0.612–0.629)] and BRI [AUC 0.620 (95% CI 0.612–0.628)], which showed nearly identical predictive accuracy. ABSI showed the weakest discrimination ability, with an AUC of 0.577 (95% CI 0.569–0.586). These results suggest that the C-index is relatively more effective in distinguishing individuals with accelerated aging.

Discussion

This study investigates the relationships between various anthropometric indices and biological age acceleration (PhenoAgeAccel) in a large, diverse cohort of American adults. The findings demonstrate that higher values of these indices are significantly associated with increased biological age acceleration, as measured by both PhenoAgeAccel and KDM-AA. These associations persisted even after adjusting for potential confounders, highlighting the robustness of these anthropometric measures as predictors of biological aging. The restricted cubic spline regression analyses highlighted significant non-linear relationships between the anthropometric indices and PhenoAgeAccel. These findings suggest that the risk of accelerated aging increases markedly beyond certain thresholds for each index, emphasizing the need for nuanced interpretations of these metrics. The subgroup analyses further underscored the importance of considering demographic and health-related factors in the assessment of biological aging. The associations between the anthropometric indices and biological age acceleration were generally robust across various subgroups defined by age, hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD) history, dietary energy intake, and physical activity levels. Significant interactive effects were observed for age, race, hypertension, diabetes, CVD history, dietary energy intake, and physical activity levels in the associations between the anthropometric indices and PhenoAgeAccel. These findings underscore the importance of considering demographic and health-related factors in assessing and managing the risks associated with these anthropometric indices, particularly for older adults, individuals with hypertension, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease, and certain racial and age groups.

Other studies have also reported on the relationship between anthropometric indices and aging. For example, Finnish Twin Cohort found significant associations of BMI with age acceleration, and an accelerated epigenetic age of 1.02 months per one-unit BMI increase28. It has also been reported that individuals with a high BMI were predicted to be, on average, approximately 1.4 years older than their actual age, a phenomenon not observed in the normal BMI group29. Moreover, other studies have reported that higher BMI in children aged 8–14 years predicts epigenetic aging30. This aligns with our findings and suggests that the association between obesity and accelerated epigenetic aging begins early in life. Other study also reported C-index predicts all-cause mortality in older people25. The ROC curve results showed that the AUC of the C-index in predicting all-cause mortality was 0.63325. Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed a clear dose–response relationship between C-index and all-cause mortality25. The relationship between anthropometric indices and aging may be attributed to the potential of obesity to accelerate the aging process, as demonstrated by substantial evidence. Diseases related to obesity seem to be linked to the acceleration of cellular processes typically observed during normal aging31. The notable similarities between chronic obesity-related pathologies and those associated with normal aging, including organ deterioration, suggest that obesity may hasten the onset of age-associated diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative conditions11,32,33.

The ROC curve analysis revealed that the C-index had the highest predictive capability for biological age acceleration risk, followed by BMI and BRI, which showed similar performance. These results suggest that the C-index may be the most effective metric for assessing the risk of accelerated biological aging, potentially due to its consideration of both weight and waist circumference, providing a more comprehensive measure of central obesity. Interestingly, ABSI exhibited the lowest predictive power in our study. However, other study also found that ABSI are significant predictors of all-cause mortality among the old34, and even more strongly and independently associated with mortality risk among older adults compared to BMI35. Krakauer and Krakauer in 2012 firstly identified ABSI as a strong predictor of mortality, independent of BMI17. ABSI is designed to account for abdominal obesity by incorporating waist circumference in relation to height and weight. Central obesity has a strong link to metabolic and cardiovascular health, which are critical determinants of mortality risk. This explains why ABSI might be a strong predictor of mortality, as it effectively captures the risk associated with fat distribution around vital organs. While central obesity contributes to biological aging, PhenoAgeAccel includes a wider array of biomarkers beyond those related to fat distribution.

This study also has some limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of NHANES data limits our ability to draw causal inferences. Longitudinal studies are needed to confirm the directionality of the observed relationships between anthropometric indices and biological age acceleration. Next, despite comprehensive adjustment for covariates, the possibility of residual confounding remains. Unmeasured factors, such as genetic predispositions or unreported lifestyle behaviors, could influence the associations observed. Then, anthropometric measurements and biomarker data may be subject to measurement errors, which could affect the accuracy of the biological age estimates and the associations with anthropometric indices. Besides, the findings are based on U.S. population data and may not be directly applicable to other populations with different genetic, environmental, and lifestyle characteristics. Finally, the use of single time point measurements for both anthropometric indices and biomarkers may not capture the dynamic nature of body composition and aging processes. Repeated measures over time would provide a more accurate assessment of these relationships.

All in all, our findings provide new perspectives on the utility of anthropometric indices in predicting biological age acceleration. Given the rising prevalence of obesity and its associated health risks, these indices can serve as valuable tools in public health surveillance and individual health assessments. The superior predictive capability of the C-index suggests it should be prioritized in clinical and public health settings for identifying individuals at higher risk of accelerated aging. Future research should continue to explore these associations in diverse populations and investigate the underlying mechanisms driving these relationships.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study revealed significant associations between elevated anthropometric indices (ABSI, BRI, BMI, and C index) and increased biological age acceleration (PhenoAgeAccel) in American adults, even after adjusting for potential confounders. The ROC curve analysis demonstrated that the C-index had the highest predictive capability for biological age acceleration risk. This research provides a new perspective on the relationship between obesity indices and biological aging acceleration.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are publicly available from the National Center for Health Statistics at https://www.n.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.

References

Nations U. World Population Ageing 2019 (The United Nations, 2019).

Rae, M. J. et al. The demographic and biomedical case for late-life interventions in aging. Sci. Transl. Med. 2(40), 40–21 (2010).

Ferrucci, L., Hesdorffer, C., Bandinelli, S. & Simonsick, E. M. Frailty as a nexus between the biology of aging, environmental conditions and clinical geriatrics. Public Health Rev. 32, 475–488 (2010).

Ferrucci, L., Levine, M. E., Kuo, P.-L. & Simonsick, E. M. Time and the metrics of aging. Circ. Res. 123(7), 740–744 (2018).

Diebel, L. W. M. & Rockwood, K. Determination of biological age: geriatric assessment vs biological biomarkers. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 23(9), 104 (2021).

Greenberg, A. S. & Obin, M. S. Obesity and the role of adipose tissue in inflammation and metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 83(2), 461s-s465 (2006).

Fontaine, K. R., Redden, D. T., Wang, C., Westfall, A. O. & Allison, D. B. Years of life lost due to obesity. JAMA 289(2), 187–193 (2003).

Tchkonia, T. et al. Fat tissue, aging, and cellular senescence. Aging Cell 9(5), 667–684 (2010).

Tzanetakou, I. P., Katsilambros, N. L., Benetos, A., Mikhailidis, D. P. & Perrea, D. N. “Is obesity linked to aging?”: adipose tissue and the role of telomeres. Ageing Res. Rev. 11(2), 220–9 (2012).

Yazdi, F. T., Clee, S. M. & Meyre, D. J. P. Obesity genetics in mouse and human: back and forth, and back again. Peer J. 3, e856 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Obesity-induced oxidative stress, accelerated functional decline with age and increased mortality in mice. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 576, 39–48 (2015).

Salmon, A. B. Beyond diabetes: does obesity-induced oxidative stress drive the aging process?. Antioxidants. 5(3), 24 (2016).

Nuttall, F. Q. Body mass index: Obesity, BMI, and health: A critical review. Nutr. Today. 50(3), 117–128 (2015).

Rey-López, J. P., de Rezende, L. F., Pastor-Valero, M. & Tess, B. H. The prevalence of metabolically healthy obesity: a systematic review and critical evaluation of the definitions used. Obes. Rev. 15(10), 781–790 (2014).

Nevill, A. M., Stewart, A. D., Olds, T. & Holder, R. Relationship between adiposity and body size reveals limitations of BMI. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 129(1), 151–156 (2006).

Gómez-Ambrosi, J. et al. Body mass index classification misses subjects with increased cardiometabolic risk factors related to elevated adiposity. Int. J. Obes. (2005) 36(2), 286–94 (2012).

Krakauer, N. Y. & Krakauer, J. C. A new body shape index predicts mortality hazard independently of body mass index. PLoS ONE 7(7), e39504 (2012).

Christakoudi, S. et al. A Body Shape Index (ABSI) achieves better mortality risk stratification than alternative indices of abdominal obesity: results from a large European cohort. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 14541 (2020).

Lee, D. Y., Lee, M. Y. & Sung, K. C. Prediction of mortality with a body shape index in young Asians: Comparison with body mass index and waist circumference. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 26(6), 1096–1103 (2018).

Thomas, D. M. et al. Relationships between body roundness with body fat and visceral adipose tissue emerging from a new geometrical model. Obesity 21(11), 2264–2271 (2013).

Nkwana, M. R., Monyeki, K. D. & Lebelo, S. L. Body roundness index, a body shape index, conicity index, and their association with nutritional status and cardiovascular risk factors in South African rural young adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 18(1), 281 (2021).

Valdez, R. A simple model-based index of abdominal adiposity. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 44(9), 955–956 (1991).

Roriz, A. K. et al. Evaluation of the accuracy of anthropometric clinical indicators of visceral fat in adults and elderly. PLoS ONE 9(7), e103499 (2014).

Eickemberg, M. et al. Abdominal obesity in ELSA-Brasil (Brazil’s Longitudinal Study of Adult Health): construction of a latent gold standard and evaluation of the accuracy of diagnostic indicators. Ciencia Saude Coletiva. 25(8), 2985–2998 (2020).

Zhang, A. et al. Conicity-index predicts all-cause mortality in Chinese older people: a 10-year community follow-up. BMC Geriatr. 22(1), 971 (2022).

Thomas, D. M. et al. Relationships between body roundness with body fat and visceral adipose tissue emerging from a new geometrical model. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 21(11), 2264–2271 (2013).

Kwon, D. & Belsky, D. W. A toolkit for quantification of biological age from blood chemistry and organ function test data: BioAge. GeroScience. 43(6), 2795–2808 (2021).

Lundgren, S. et al. BMI is positively associated with accelerated epigenetic aging in twin pairs discordant for body mass index. J. Intern. Med. 292(4), 627–640 (2022).

Salas-Huetos, A. et al. The combined effect of obesity and aging on human sperm DNA methylation signatures: inclusion of BMI in the paternal germ line age prediction model. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 15409 (2020).

Etzel, L. et al. Obesity and accelerated epigenetic aging in a high-risk cohort of children. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 8328 (2022).

Ahima, R. S. Connecting obesity, aging and diabetes. Nat. Med. 15(9), 996–997 (2009).

Tchkonia, T. et al. Fat tissue, aging, and cellular senescence. Aging Cell 9(5), 667–684 (2010).

Salmon, A. B. Beyond diabetes: Does obesity-induced oxidative stress drive the aging process?. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland). 5(3), 24 (2016).

Yang, N. et al. A body shape index and its changes in relation to all-cause mortality among the Chinese elderly: A retrospective cohort study. Nutrients 15(13), 2943 (2023).

Shafran, I., Krakauer, N. Y., Krakauer, J. C., Goshen, A. & Gerber, Y. The predictive ability of ABSI compared to BMI for mortality and frailty among older adults. Front. Nutr. 11, 1305330 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr. Fengping Zhang for the guidance and suggestions on the statistics in this article.

Funding

The work was supported by Sichuan Medical Association Nephrology Special Project (Grant No. 2024SY01), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No.2020JDRC0022) and 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence from West China Hospital of Sichuan University (ZYGD23015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Y.C.: conceptualization and writing; X.C.: Major revisions, critical editing, and responding to reviewer comments; F.Y.S.: data acquisition; W.H.Y. and C.G.: statistical analysis and writing; S.J.G. and P.F.: review, editing, and supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research analyzed de-identified information downloaded from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey public database. The National Center for Health Statistics Ethics Review Committee granted ethics approval. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations (declaration of Helsinki). All individuals provided written informed consent before participating in the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Chen, X., Shi, F. et al. Associations between anthropometric indices and biological age acceleration in American adults: insights from NHANES 2009–2018 data. Sci Rep 15, 22691 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08559-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08559-1