Abstract

Sorghum bicolor is a drought- and heat-tolerant cereal widely cultivated in arid regions. However, like other important grasses, it is susceptible to ergot disease caused by Claviceps species, which infect ovary tissues and reduce grain yield. To combat this disease, targeted biotechnological strategies are needed. In this study, we conducted a genome-wide identification and classification of lipid transfer proteins (LTPs) in S. bicolor, uncovering 68 putative genes grouped into five families. In silico analyses of gene expression and promoter sequences identified two LTP genes, SbLTP1.4 and SbLTP1.5, as strong candidates for flower-specific biotechnological applications. Their promoters were functionally tested in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana, revealing distinct spatial and stress-responsive expression profiles. The SbLTP1.4 promoter was active in stigmas, floral peduncles, styles, and young leaves, and was strongly induced by both biotic and abiotic stress. In contrast, SbLTP1.5 promoter displayed low and stigma-specific expression, with no detectable stress responsiveness. Promoter analysis also revealed conserved transcription factor binding sites across orthologous genes in other economically important grasses, supporting the potential transferability of this strategy to related species. These findings introduce novel tissue-specific promoters for the targeted expression of antimicrobial proteins in reproductive tissues, offering a promising tool to control Claviceps infections and enhance crop resilience in cereals and forage grasses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

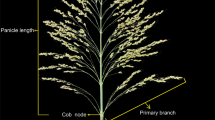

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor [L] Moench) is an important cereal crop widely cultivated for both forage and grain. Its remarkable tolerance to drought, elevated temperatures, and high water-use efficiency makes it an ideal crop for arid and semi-arid regions. Forage sorghum is widely grown as a drought-resistant alternative to maize in arid subtropical to warm temperate regions. It holds promise as a biofuel source on marginal lands unsuitable for food production1. Being a C4 plant, sorghum boasts improved photosynthetic efficiency and reduced water loss in hot and dry environments— valuable amidst current global climate change, limited access to fertilizers, and diminishing arable land2.However, sorghum faces challenges from Ergot, a disease caused by fungi belonging to the genus Claviceps. Ergot infects young, often unfertilized ovaries, replacing the seeds with dark mycelial masses called sclerotia. The alkaloids produced by the fungus severely impact the health of humans and warm-blooded animals. Ergot-related issues also affect commercial seed production in infected crops3.

Non-specific lipid transfer proteins (LTPs) were discovered approximately 30 years ago4. These proteins are abundant, secreted, soluble, cysteine (Cys)-rich, and typically small, with a molecular size usually below 10 kDa5,6,7. LTPs proteins family evolved after plants adapted to land, as they are present in liverworts, mosses, and other land plants but not in algae. They are classified into five major types (LTP1, LTP2, LTP-C, LTP-D, and LTP-G) based on the spacing between the Cys residues in the eight-cysteine motif, the polypeptide sequence identity, and the position of evolutionarily conserved introns6,8. Although the in vivo functions of LTPs remain unclear, accumulating evidence suggests diverse roles for LTPs in plant physiology. These roles include involvement in cutin synthesis, β-oxidation, somatic embryogenesis, allergenic properties, plant signaling, and plant defense against phytopathogens5,6.

LTP genes exhibit complex expression patterns, both temporally and spatially, making them excellent candidates for tissue-specific expression studies. Numerous studies have demonstrated LTP expression in floral organs5,7,9. These genes are notably active during early flower development and are highly expressed in inflorescences across a range of plant species. High transcript levels have been reported in young developing inflorescences of carrot and Arabidopsis thaliana, the sepals of unopened tobacco flowers, the flower buds of broccoli, the microspores of rapeseed, and the corolla and carpel of Gerbera hybrida. While some LTPs exhibit exclusive expression in floral tissues, others are expressed in multiple organs10.

In addition to their floral-specific expression, many LTP genes respond to various environmental signals, including salinity, drought, extreme temperatures, heavy metals, and biotic stresses such as bacterial and fungal pathogen attacks5,6,11. These dual characteristics—floral-specific expression and environmental responsiveness—underscore the suitability of LTP promoters for targeted gene expression in floral organs, particularly for strategies aimed at combating stresses like fungal infections.

Plant genetic engineering plays a pivotal role in introducing valuable traits that enable crops to thrive with reduced dependence on pesticides, fungicides, and fertilizers, while enhancing stress resistance. Using organ-specific, developmentally and stress-induced promoters is vital for genetically modifying plants. While constitutive and non-specific promoters are useful in proof-of-concept experiments, their application in genetically improved crops presents potential drawbacks12,13. Overexpression of proteins in excessive amounts or at unnecessary times can strain cellular energy reserves14 or result in undesirable pleiotropic effects in transgenic plants15,16. One way to minimize these problems is by using endogenous regulatory regions from promoters with well-defined developmental expression patterns17,18. Thus, achieving precise temporal and tissue-specific expression of foreign genes through promoter control is crucial17,19.

This study performed a genome-wide identification of LTP genes in S. bicolor and classified them based on structural analysis and in silico expression patterns to identify flower tissue-specific promoters. Given the specificity of Claviceps infection in sorghum, stigma-specific promoters for expressing antifungal compounds in floral organs represent a promising strategy to disrupt the infection process by preventing the germination of ascospores or the development of infectious hyphae. Since Claviceps targets several agriculturally important species, including Sorghum, Zea, Pennisetum, Setaria, and others, this approach has the potential to significantly reduce economic losses and improve the productivity of food and forage crops. These findings highlight the functional diversity of LTPs in S. bicolor and establish tissue-specific promoters as valuable tools for targeted antimicrobial protein expression, laying a foundation for enhancing crop resilience and combating ergot disease in cereals and forages.

Results

Identification and classification of putative LTPs genes in the S. bicolor genome

To identify all putative, non-redundant LTPs genes within the S. bicolor genome, we conducted an exhaustive search and data mining process according to the workflow chart presented in Fig. 1. First, we retrieved putative LTPs sequences from S. bicolor genome using two hidden Markov models (HMM) profiles developed for protease inhibitor, seed storage and LTP proteins (PF14368 and PF00234). Subsequently, we performed a Blastp search using previously reported LTPs protein sequences in Z. mays and O. sativa20and a keyword search against the Uniprot database. These additional methods led to the discovery of novel sequences, which were integrated with the initial dataset. We removed redundant sequences, resulting in 116 non-redundant amino acid sequences.

LTPs are typically produced as pre-proteins, which include an N-terminal signal peptide necessary for their correct secretion to their subcellular location21. To ensure the inclusion of proteins with such signal peptides, we conducted N-terminal signal sequence (NSS) prediction and excluded proteins lacking in them (Table S2). On the other hand, the members of the LTP-G protein subgroup are characterized by having a C-terminal motif that undergoes post-translational modification in the endoplasmic reticulum through adding a GPI moiety21. This modification enables the protein to anchor to the outer side of the plasma membrane20. Therefore, we also conducted predictions for C-terminal glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor signals. Finally, we excluded sequences belonging to alpha-amylase/trypsin inhibitors, proline-rich proteins or hybrid proline-rich proteins, and glycine-rich proteins (Table S2). The remaining deduced protein sequences were thoroughly examined for the presence of the characteristic 8CM motif of LTPs, and proteins lacking these motifs were removed. Consequently, a total of 68 sequences were isolated, identified as putative LTP genes in the S. bicolor genome, and designated as SbLTPs (Table 1, Table S2).

Applying the classification system developed by Edstam et al.8 This pattern of conservation and diversification underscores the importance of gene duplication and subsequent adaptation in the evolution of LTPs, with different types evolving to fulfill specific roles in response to environmental pressures and unique functional requirements., we categorized the sequences into five LTP types. Proteins that met the LTP criteria but did not align with any of the five LTP groups, due to the 8CM motifs or intron position not precisely matching the pattern described by Edstam et al.8were assigned to the non-determined (ND) category. In the ND category, we found two subgroups that, according to the phylogenetic analysis (Fig. S4), are related to groups LTP-G and LTP-D. In the case of the Type G proteins, these appear to have lost the GPI-anchor site (Table 1). Specifically, we identified 9 LTP-1, 7 LTP-2, 2 LTP-C, 12 LTP-D, 20 LTP-G, and 18 LTP-ND.

To analyze the sequence characteristics of SbLTPs, we performed a multiple sequence alignment using the deduced mature proteins from the 68 SbLTP for each LTP subgroup (Fig. 2). The main characteristic of all plant LTPs is the presence of a highly conserved 8CM (C1-Xn-C2-Xn-C3C4-Xn-C5XC6-Xn-C7-Xn-C8), which enables the formation of four disulfide bonds, crucial for stabilizing the three-dimensional structure of the protein, allowing it to interact with lipids and facilitate their transfer between biological membranes22. Each LTP subgroup has a characteristic arrangement of the 8CM motif, with the spacing and specific sequence varying between types (Table 1; Fig. 2). Additionally, a high conservation of other amino acids (P, L, V, Y) is observed, which differ among subtypes and could be essential for their function and/or functional specificity23. Regarding the CXC motif, type 1 SbLTP displayed variability in the residues at the X position (Ser, Gly, Glu, Asn, Ala, Arg), with five sequences having hydrophilic residues and four sequences having hydrophobic residues. On the other hand, types 2, C, D, and G SbLTPs exhibited hydrophobic residues at this position.

Chromosomal locations and gene duplication of putative SbLTPs

The chromosome locations of each gene were determined using information from the NCBI Genome Browser, and a physical map was constructed (Fig. 3). The exact positions of SbLTPs on chromosomes are detailed in Table S3. The chromosomal location analysis revealed that the 68 SbLTP genes were unevenly distributed across the ten S. bicolor chromosomes, with most genes organized into clusters. The largest clusters are on chromosomes 1, 2, and 3, with the highest numbers of SbLTP genes found on chromosomes 1 (15) and 2 (18), while chromosome 4 had the lowest number (1). LTPs are predominantly situated towards the distal ends of the chromosomes, often away from the centromere regions on both arms. However, several chromosomes lacked SbLTPs in specific regions, such as the short arms of chromosomes 4, 6, 9, and 10, as well as the long arm of chromosome 8. Additionally, we identified five tandem LTP repeats in the S. bicolor genome: (1) SbLTP2.1/SbLTP2.2, (2) SbLTPnd15/SbLTPnd16, (3) SbLTPd5/SbLTPd6, (4) SbLTP1.4/SbLTP1.5 and (5) SbLTPd7/SbLTPd11. Each tandem repeat comprised genes of the same LTP type, indicating they likely originated from gene duplication events.

Chromosomal localization of the putative SbLTP genes. Chromosomes are depicted by cylinders with the chromosome numbers indicated at the bottom of each cylinder. Gene names are listed along the sides of each chromosome correspond to the approximate locations of each LTP gene. The tandem-duplicated gene clusters are marked in boxes. Centromere positions are indicated with black circles to help distinguish the relative position of genes in chromosomal arms.

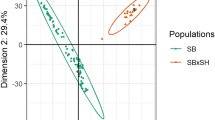

To analyze evolutionary relationships, a phylogenetic tree of LTPs from A. thaliana, O. sativa, and S. bicolor was constructed. Our analysis confirmed the Edstam classification, showing that the five groups in the SbLTP classification align with types 1, 2, C, D, and G from the other species, with some overlap in types D and G (Fig. S2). Types 1, 2, and C formed distinct clades with over 95% bootstrap support, indicating a common ancestor for each group. LTPs-G were further divided into three clades, and LTPs-D into two, reflecting additional diversification. Notably, 9 ND SbLTPs (SbLTPnd3-SbLTPnd11) clustered with LTPs-G, suggesting these proteins may belong to the G group but could have lost the GPI anchor and undergone subfunctionalization to fulfill new roles distinct from their ancestral functions.

To further characterize the SbLTP proteins, we analyzed their theoretical isoelectric point (pI) and molecular weight (MW). As shown in Table 1, type G and ND SbLTPs have the highest molecular weights, averaging 15 kDa, while types 2 and C have the lowest, averaging 7 kDa. Regarding pI, LTPs-1, LTPs-C, LTPs-D, and LTPs-G show a range of both basic and acidic values, whereas LTPs-2 are predominantly basic (Table 1). Notably, LTPs 2.1/2.2 and ND15/ND16, which originated from tandem duplications (Fig. 3), exhibit significantly different pI values, one being basic and the other acidic. This variation suggests functional diversification resulting from these duplication events.

In silico expression analysis and selection of candidate SbLTP genes for promoter characterization

Plant LTPs exhibit complex tissue-specific and developmental expression patterns11. To explore the expression profiles of all 68 predicted SbLTPs, we analyzed RNA-seq datasets from various tissues. Expression patterns varied significantly among the different groups. Notably, only two SbLTPs (SbLTP1.9 and SbLTP2.4) showed no detectable expression, which may indicate they function as pseudogenes or that their expression is limited to specific tissues or conditions not covered by the RNA-seq datasets (Fig. 4).

SbLTP-1 genes are predominantly characterized by ubiquitous expression, with high levels in reproductive tissues and low or negligible levels in roots. In contrast, SbLTP-2 and SbLTP-D genes exhibit low to intermediate expression levels and a more tissue-specific expression pattern. For example, SbLTP2.2, SbLTP2.6, and SbLTP2.7, SbLTPd3, SbLTPd7 and SbLTPd9 are exclusively expressed in seeds. SbLTP-C genes are specifically expressed in anthers and microspores, indicating a male-specific role in reproduction. Within the SbLTP-G group, there are both ubiquitous and tissue-specific expression profiles. In this group ubiquitous genes generally have strong to moderate expressions in roots and seedlings. The ND type LTPs mostly exhibit low, tissue-specific expression, except for SbLTPnd-2, SbLTPnd-14, and SbLTPnd-18, which show different patterns.

Expression profile of SbLTP genes across various anatomical structures. The data were obtained from the Genevestigator database and are represented using a color scale indicating expression levels according to the “percent of expression potential” (PEP) metric, shown on a log₂ scale. Genevestigator expression data for each gene can be retrieved using the corresponding locus ID listed in Table S2.

To identify promoters with high expression in target tissues, we focused on SbLTP genes with preferential and high expression in female reproductive tissues, particularly in pistils. To minimize the potential environmental impact of AMP expression, genes with high expression in roots or pollen were excluded. Based on these criteria, we identified eight candidate genes (SbLTP1.2, SbLTP1.4, SbLTP1.5, SbLTP2.1, SbLTPg1, SbLTPg7, SbLTPg13, and SbLTPg16) that met the requirements. Type 1 LTPs are known to respond to both biotic and abiotic stress24,25,26,27,28which makes them ideal candidates for promoters aimed at expressing biological control proteins. Given this, we chose SbLTP1.4 and SbLTP1.5 for further isolation and characterization of their promoters.

Identification of conserved transcription factor binding sites in the LTP promoters of S. bicolor and related grass species

To identify conserved transcription factor (TF) binding sites within the promoters of selected SbLTP genes, we performed an in silico analysis using the MEME and TOMTOM software tools29,30. We examined the promoters SbLTP1.4 and SbLTP1.5, as well as their orthologous genes in related grass species (O. sativa, S. italica, Z. mays, and P. hallii) to identify putative TFs involved in stress responses. MEME identified four de novo regulatory motifs (Fig. 5). The localization of consensus sequences for each identified TF on the promoter sequences is shown in Fig. S5.

Motif 1 matches a cis-regulatory element recognized by AtMYB31, an R2R3-MYB transcription factor (TF) involved in regulating wax biosynthesis in reproductive tissues and playing a role in seed development in A. thaliana31. Additionally, MYB TFs, including AtMYB31, have been shown to modulate plant defense against fungal pathogens32,33. Furthermore, members of the MYB family are crucial for plant responses to abiotic stresses, enhancing salt and drought tolerance in species such as Triticum aestivum34 and A. thaliana35.

Motif 2 corresponds to a cis-element recognized by AGL55 (AGAMOUS-like 55), a TF from the MADS-box family. AGL55 plays a critical role in regulating stamen and carpel identity and in determining floral meristem identity36.

Motif 3 corresponds to the binding regulatory elements for two transcription factors: DREB2C and ERF015. DREB (Dehydration Responsive Element Binding) TFs, part of the AP2/ERF family, play a significant role in plant responses to various stressors such as drought, high salinity, cold, and heat. These TFs enhance plant tolerance by binding to DRE/CRT cis-elements in the promoter regions of stress-responsive genes37. Specifically, DREB2C recognizes and binds to the consensus sequence 5’-[AG]CCGAC-3’, mediating responses related to high salinity and abscisic acid (ABA)38. Additionally, DREB2C is upregulated during heat stress, indicating its involvement in heat acclimation in A. thaliana39. Conversely, ERF family genes exhibit varied expression patterns during plant growth and development, as well as in response to stress-related stimuli such as ethylene, jasmonic acid, and salicylic acid, or abiotic stress conditions40,41. ERF015 positively regulates responses to ABA and may contribute to plant tolerance to salinity and drought42.

Conserved motifs and transcription factor binding sites identified in the promoter sequences of LTP1.4 and LTP1.5 and their orthologos from grass species. The Logo column displays the conserved sequences (de novo motifs) detected by the MEME tool, along with the occurrence (Oc) within the input sequences. The Name and Sequence columns provide the binding sequences of the TFs identified in the JASPAR Plants database. The figure also includes the significance of MEME motifs (E-value) and TFs (p-value), along with their associated biological functions as found in the UniProt database. GO: Gene Ontology.

Motif 4 corresponds to binding elements for ABI3, FUS3, and LEC2 transcription factors from the B3 family. These TFs form a regulatory network involved in embryo development, ABA signaling, and stress responses43. ABI3 is crucial for embryo development, ABA signaling, and tolerance to freezing, desiccation, and dehydration44,45,46,47,48. Interestingly, ABI3 from the desert moss Syntrichia caninervis was shown to enhance salinity and osmotic stress tolerance in A. thaliana transgenic plants49. FUS3 also plays a role in stress responses, including inhibition of seed germination at high temperatures and drought tolerance37,50.

Spatio-temporal expression patterns of pSbLTP-GUS constructs in A. thaliana transgenic plants

Two independent homozygous lines for each construct (pSbTLP1.4-GUS-1, pSbTLP1.4-GUS-2, pSbTLP1.5-GUS-1 and pSbTLP1.5-GUS-2) were selected for spatial and temporal GUS expression analysis.

In six-day-old seedlings of the pSbLTP1.4-GUS-1 line, notable GUS expression was observed in leaf primordium trichomes, cotyledons, and hypocotyls. In 55-day-old pSbLTP1.4-GUS-1 plants, GUS expression was detected in the floral peduncle, receptacle, style, and stigma, but not in male reproductive structures. Expression was also noted in the silique valves (but not in seeds) and weakly in rosette leaves. The pSbLTP1.4-GUS-2 line showed a similar expression pattern, although with lower reporter gene intensity (Fig. 6A, Fig. S6). An evaluation throughout plant development confirmed that the expression of the pSbTLP1.4-GUS construct is restricted to the aerial parts of the plant (Fig. S7).

For the pSbLTP1.5-GUS construct, both transgenic lines generally exhibited very low or no detectable GUS expression in seedlings and adult plants (Fig. 6B, Fig. S7). Only the pSbLTP1.5-GUS-1 line showed specific expression of the reporter gene in the stigma (Fig. 6B). The wild-type plants used as a negative control in the experiment did not show any evident GUS signal (Fig. S8).

Anatomical-specific expression profiling of the pSbLTP1.4-GUS (A) and pSbLTP1.5-GUS (B) constructs in transgenic A. thaliana plants. The expression patterns of the GUS reporter gene in vegetative and reproductive structures are shown for two homozygous lines of each construct. Seedling 0.2 mm. Flowers 0.5 mm. Inflorescences, siliques, leaves and roots 1 mm.

Response of pSbLTP-GUS constructs to biotic and abiotic stresses in A. thaliana transgenic plants

To evaluate the response of the pSbLTP1.4-GUS and pSbLTP1.5-GUS constructs to various biotic and abiotic stress conditions, we subjected transgenic A. thaliana plants to a range of stressors, including Pseudomonas syringae infection, osmotic stress induced by mannitol, and high salinity stress.

During the seedling stage, plants infected with P. syringae to simulate pathogen stress exhibited distinct responses. pSbLTP1.4-GUS seedlings displayed a marked increase in GUS expression, with intense reporter gene activity across the entire surface of cotyledons and leaves (Fig. 7A), indicating strong activation of the SbLTP1.4 promoter under biotic stress. In contrast, pSbLTP1.5-GUS plants and non-transgenic controls showed only weak GUS staining, confined to the edges of cotyledons and trichomes of young leaves, regardless of infection presence (Fig. 7A).

Abiotic stress treatments further highlighted these differences. Saline conditions significantly increased GUS staining in pSbTLP1.4-GUS-1 transgenic plants. While control seedlings showed reporter gene activity limited to specific areas, such as cotyledons, leaf trichomes, and hypocotyls, exposure to 100 and 200 mM NaCl resulted in a notable increase in GUS expression throughout the entire seedling (Fig. 7B). A similar response was observed in seedlings treated with 100 and 200 mM mannitol (Fig. 7C). Conversely, transgenic seedlings carrying the pSbLTP1.5-GUS construct showed no reporter gene expression under any of the abiotic stress conditions tested (Fig. 7B,C).

Response of pSbLTP1.4-GUS and pSbLTP1.5-GUS constructs to biotic and abiotic stress at the seedling stage. Wild-type (Col-0) and transgenic A. thaliana seedlings (pSbLTP1.4-GUS and pSbLTP1.5-GUS) were inoculated with P. syringae (A) and exposed to salt stress (B) and osmotic stress (C). GUS expression was assessed 3 days post-inoculation for P. syringae and 24 h post-treatment for both salt and osmotic stress conditions. Seedlings 0.2 mm.

To assess the stress response of the pSbLTP1.4 and pSbLTP1.5 promoters during plant adulthood, we conducted biotic and salt stress experiments on transgenic A. thaliana lines at the mature reproductive stage. Inoculation with P. syringae maintained the same pattern but markedly increased the intensity of GUS staining in pSbTLP1.4-GUS-1 plants relative to control plants. GUS expression was detected in the floral peduncle, receptacle, style, stigma, cauline leaves, and silique valves, but not in rosette leaf laminae (Fig. 8A) or roots (Fig. S7). At this stage, both promoters showed expression in female reproductive tissues. However, pSbLTP1.5-GUS-1 consistently exhibited very weak expression at the stigma and no detectable expression in other tissues. Additionally, saline treatment with 100 and 200 mM NaCl produced results like those observed under biotic stress for pSbLTP1.4-GUS-1 plants, with very strong blue staining in reproductive tissues, including siliques, and no significant differences between the two salt concentrations tested (Fig. 8B). In contrast, pSbLTP1.5-GUS-1 plants did not show any reporter gene signal in response to the stress conditions tested (Fig. 8).

Response of pSbLTP1.4-GUS and pSbLTP1.5-GUS constructs to biotic and abiotic stress at the adult plant stage. Wild type (Col-0) and transgenic A. thaliana plants carrying the pSbLTP1.4-GUS and pSbLTP1.5-GUS constructs were subjected to biotic and abiotic stress conditions. Plants were inoculated with P. syringae (A) and exposed to salt stress (B). GUS expression was evaluated 3 days post-inoculation for bacterial infection and 48 hs post-treatment for both salt and osmotic stress. Leaves, inflorescences, siliques 1 mm.

Discussion

Claviceps species cause ergot disease in cereals and forage grasses, forming sclerotia in place of grains and leading to considerable economic losses. This contamination affects flour quality due to ergot alkaloids, which are also harmful to mammals1,3,51. Due to the absence of known resistance genes, transgenic strategies targeting the site of infection are promising. This study contributes to such efforts by identifying reproductive tissue-specific promoters from the LTP family in S. bicolor.

We identified 68 LTPs in the S. bicolor genome and classified them into five subfamilies using Edstam’s classification system, which evaluates structural and biochemical features to provide a more robust framework than traditional approaches52. Our comprehensive analysis revealed LTPs that had not been previously identified in sorghum20.

Phylogenetic and structural analyses revealed that S. bicolor LTPs, along with those from A. thaliana and O. sativa, are distributed across all five subfamilies. The proportion of S. bicolor LTPs varied across subfamilies, with members of the same subgroup exhibiting conserved exon-intron structures. The presence of distinct clades for types LTPs type 1, 2, and C with over 95% bootstrap support suggests that these groups have maintained a strong evolutionary identity, likely due to essential functions preserved from a common ancestor. In contrast, the greater diversification observed in types G and D, which formed multiple clades, may reflect a higher degree of evolutionary flexibility, allowing these types to adapt to different functional roles. The clustering of the undetermined SbLTPs (ND) with the LTP-G group, together with the loss of the GPI anchor, suggests that these genes may have undergone subfunctionalization or neofunctionalization, potentially acquiring specialized or novel roles distinct from those of their ancestral counterparts. Research on lipid transfer proteins (LTPs) shows that they are often organized in clusters, with many arising from tandem duplications53,54,55,56. We identified five tandem duplications, such as SbLTP1.4/SbLTP1.5, SbLTP2.1/SbLTP2.2, SbLTPd5/SbLTPd6, and SbLTPd7/SbLTPd11 and SbLTPnd15/SbLTPnd16. While some pairs exhibited similar expression profiles, others did not; for example, SbLTP2.1 is flower-specific, whereas SbLTP2.2 is seed-specific. This pattern of conservation and diversification underscores the importance of gene duplication and subsequent adaptation in the evolution of LTPs, with different types evolving to fulfill specific roles in response to environmental pressures and unique functional requirements.

Two LTPs, SbLTP1.4 and SbLTP1.5, were selected for promoter analysis based on their in silico expression patterns. Spatio-temporal evaluationrevealed that both promoters drive gene expression exclusively in the aerial structures of the plant. This is likely related to cutin deposition associated with the lipid transport function characteristic of these proteins, which explains the absence of expression in roots57. In transgenic A. thaliana lines carrying the pSbLTP1.4-GUS construct, GUS staining was observed in vegetative structures such as the hypocotyl, cotyledons, and trichomes of leaf primordia. In reproductive structures, GUS expression was detected in peduncles, floral receptacles, styles, and stigmas, with no expression in male floral organs. These results align with the in silico expression profile of SbLTP1.4 reported for sorghum. In contrast, the SbLTP1.5 promoter exhibited very low activity, restricted solely to stigmas, which unexpectedly diverges from the in silico expression profile reported by Genevestigator. However, other transcriptomic studies in sorghum corroborate our findings, showing that SbLTP1.5 displays significantly lower expression levels than SbLTP1.4 in inflorescences9. This discrepancy highlights the limitations of transcriptomic methods like RT-PCR in distinguishing highly homologous genes. The high sequence similarity between these paralogs could bias detection toward the more abundant transcript. Therefore, heterologous promoter testing remains a valuable approach for assessing tissue-specific expression and resolving such ambiguities.

Stress assays revealed that pSbLTP1.4 is induced by Pseudomonas syringae infection, salt, and osmotic stress. This is consistent with the presence of binding sites for stress-related transcription factors such as AtMYB31, DREB2C, ABI3, and FUS3 in its promoter region. These TFs are known regulators of biotic and abiotic stress responses and have been shown to activate LTP genes in rice and maize32,33,58,59. Conversely, pSbLTP1.5 showed no detectable response to any stress treatment. Despite sharing similar predicted TF binding sites with pSbLTP1.4, the absence of stress responsiveness suggests the involvement of additional regulatory elements not captured in our analysis. Interestingly, the expression profiles of the orthologous genes in Setaria italica mirror those observed in S. bicolor60reinforcing the functional divergence observed between these promoter.

The contrasting patterns of SbLTP1.4 and SbLTP1.5 expression reflect an evolutionary strategy of functional specialization. SbLTP1.4 combines responsiveness to multiple stresses with broad reproductive and vascular tissue expression, possibly contributing to both defense and reproductive development. SbLTP1.5, on the other hand, shows low, stigma-specific expression, suggesting a specialized role in female reproductive biology, potentially in pollen interaction. The complementary expression patterns of these two paralogs highlight an evolutionary strategy to balance tissue-specific roles with environmental responsiveness, which could be exploited in biotechnological applications aimed at enhancing disease resistance specifically in reproductive tissues without compromising overall plant fitness.

In this context, tissue-specific promoters offer a powerful strategy for targeted disease control. While some studies have shown that constitutive AMP expression does not significantly affect the rhizosphere or mammalian microbiota61,62restricting expression to infection sites remains a safer strategy to minimize ecological and physiological risks. Both pSbLTP1.4 and pSbLTP1.5 exclude root expression, preserving the soil microbiome, and effectively target reproductive tissues where Claviceps initiates infection. These features make them promising tools for engineering resistance in cereals and forage grasses while minimizing off-target effects.

Materials and methods

In silico identification and classification of putative S. bicolor LTPs

HMM profiles PF14368 (probable lipid transfer; LTP_2) and PF00234 (Protease inhibitor/seed-storage/LTP family; Tryp_alpha_amyl) were used to search against the S. bicolor genome (Sorghum bicolor v3.1.1) from the Phytozome database (https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/) using the HMMER 3.1 software (http://hmmer.org/)66. Keyword searches were conducted on the UniProt website (https://www.uniprot.org/) using the queries “LTP sorghum bicolor” and “lipid transfer protein sorghum bicolor”. Additionally, a BLASTp search was performed against the S. bicolor genome in the NCBI database using Zea mays and Oryza sativa LTPs as queries20. All results were merged, eliminating duplicate entries and incomplete sequences. Since LTPs are secreted proteins, only those with a signal peptide were retained, and TargetP-2.0 was used to detect N-terminal signal sequences, removing proteins without them67. Sequences not directly related to LTPs, such as alpha-amylase/trypsin inhibitors, glycine-rich, proline-rich proteins, and hybrids, were excluded. The GPI Plant Prediction Server68 was used to detect GPI (glycosylphosphatidylinositol) anchor recognition sites and predict potential omega sites for LTP proteins of subgroup G. As a final criterion, the presence of the 8CM was manually checked, and proteins lacking the essential cysteine residues were removed. The procedural scheme for isolating putative LTPs from the S. bicolor genome is summarized in Fig. 1.

LTP classification and multiple sequence alignment

Edstam’s classification scheme was used to group S. bicolor LTPs, which are based on sequence identity, spacing between the Cys residues, intron position in the 8CM, and the presence of (GPI) anchors as a post-translational modification8. The number and position of exons and introns were determined by comparing the coding sequences (CDSs) with their corresponding genomic DNA sequences obtained from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Theoretical molecular weight and isoelectric point were determined using Expasy Compute pI/Mw tool (https://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/)69. A multiple sequence alignment of S. bicolor LTPs was performed using the T-coffee program with the Jalview web service (https://www.jalview.org)70.

Phylogenetic construction

The LTP amino acid sequences of A. thaliana and O. sativa were obtained from Duo et al.11. Multiple alignments of the mature proteins were carried out and the phylogenetic tree was built using IQ-TREE software71with the neighbour-joining (NJ) method and 1000 bootstrap replications. The results were then imported into the iTOL online service (https://itol.embl.de/) for visualization72.

Chromosomal mapping and gene duplication

Genes were mapped on chromosomes by identifying their chromosomal position using the NCBI-Genome Data Viewer (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/gdv/). Gene duplication was defined according to the following criteria: (1) the alignment length covered > 80% of the longer gene; (2) the aligned region had an identity > 80%; (3) only one duplication event was counted for tightly linked genes73. All the relevant genes identified in the S. bicolor genome were aligned using T-coffee74and identity percentages were calculated using the Sequence Manipulation Suite online software (https://www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/ident_sim.html)75.

In silico expression profiling

The Genevestigator database76 was used to perform expression analysis for the identified S. bicolor LTPs genes. RNA-seq data was used to develop a heat map of expression profiling in different anatomical parts using hierarchical clustering tool. Expression patterns were presented as “percent of expression potential” (PEP = average expression of a gene across all the samples in a particular tissue / maximum expression value across samples) and the results were visualized as a heat map using logarithm (log2) scale.

Promoter analysis

Promoter sequences (1 kb upstream of the transcription start site) of the selected S. bicolor LTPs and their homologs in O. sativa, Setaria italica, Z. mays, and Panicum hallii were retrieved from NCBI GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The MEME de novo motif detection tool (http://meme-suite.org)30 was utilized to identify novel sequence motifs within the promoter region of LTPs. Motif length (minimum of 6 and maximum of 15 nucleotides) and distribution type (zero or one occurrence per sequence - zoops) were specified. After obtaining the results, MEME motifs containing repetitive sequences were excluded, and the remaining motifs were analyzed using the TOMTOM website (https://meme-suite.org/meme/tools/tomtom)29 to identify significant matches with known motifs in Jaspar Core Plants 2022 77. Motifs that did not match known transcription factor binding sequences, or those that did but with low conservation, were discarded. Since the MEME zoops option enables the discovery of conserved motifs present at most once per sequence, we used the Jaspar 2022 database (https://jaspar2022.genereg.net/) and input the promoter sequences to identify additional sites corresponding to the transcription factors found. Results were obtained using the default 80% reltive score threshold, and only those with a score greater than or equal to 0.85 were selected.

Construction of SbLTP promoter-GUS fusions

Promoter sequences of the SbLTP1.4 (LOC8067182) and SbLTP1.5 (LOC8067183) genes were amplified from S. bicolor genomic DNA by PCR using specific primers (Table S1) and the Platinum™ Pfx DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen, Cat. No. 11708039. The obtained fragments (982 bp for the SbLTP1.4 promoter and 998 bp for the SbLTP1.5 promoter) were cloned into the pJET1.2 vector using the CloneJET PCR Cloning Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. K1231) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The promoter sequences were then subcloned into the pKGWFS7 binary vector by Gateway technology using specific primers (Table S1). pKGWFS7 vector harbors the GUS reporter gene (coding for the enzyme beta-glucuronidase) downstream of the Gateway recombination site, allowing functional evaluation of the promoter sequences. The generated constructs (pSbLTP1.4-GUS and pSbLTP1.5-GUS) were confirmed by restriction enzyme analysis and DNA sequencing (Fig. S1 and S2).

Transformation of A. thaliana and selection of transgenic plants

Arabidopsis thaliana Col-0 ecotype seeds were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC). Transgenic lines were generated for transient assays to characterize the activity of the selected promoters. pSbLTP1.4-GUS and pSbLTP1.5-GUS constructs were separately introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 using the MicroPulser electroporator (Bio-Rad, #1652100). The transformed bacteria were then used for the stable transformation of A. thaliana Columbia-0 (Col-0) plants by the floral dip method (Fig. S1 and S2). Transgenic lines were selected on MS medium (1/2 MS, 0.7% agar, pH 5.8) supplemented with kanamycin (50 mg/L), and the presence of the constructs was verified by PCR using specific primers that amplify an internal region of the promoters (Fig. S3 and Table S1). After two rounds of self-fertilization, homozygous lines (T2) were identified based on segregation analysis (Fig. S3). GUS expression assays were performed on A. thaliana plants from the T3 generation.

Plant growth conditions

For adult plant experiments, wild-type and transgenic A. thaliana seeds were sown in pots containing a premix of GrowMix® Multipro substrate (Terrafértil). The pots were placed in a controlled growth chamber with a 16 h light / 8 h dark cycle at 23 °C, a light intensity of 150 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹, and 60% relative humidity. Plants were watered three times per week with Hakaphos Red fertilizer solution (Compo Expert), prepared and applied according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Pots were monitored to ensure consistent moisture levels throughout the growth period. For seedling assays, A. thaliana seeds were surface sterilized with chlorine gas (Cl2) for 2 h. After venting chlorine vapors, seeds were sown on 90 × 15 mm Petri dishes (8–10 seeds per plate) containing 1/2 MS medium (Sigma-Aldrich) with 0.7% agar, adjusted to pH 5.8. Plants were grown in growth chambers under a 16 h light / 8 h dark cycle at 23 °C, with a light intensity of 150 µmol m-2 s-1.

Biotic stress treatments

Biotic stress treatment was performed by infecting A. thaliana seedlings with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. For this purpose, 10 ml of KB medium supplemented with rifampicin (50 ug/ml) was inoculated with P. syringae, and then incubated under shaking at 28 °C overnight. The culture was diluted in sterile water containing 0.025% Silwet L77, and then dispersed on 14-day-old wild-type and transgenic A. thaliana plants. After three minutes, the excess culture was removed, and the plates were transferred to the growth chamber. A sterile water solution containing 0.025% Silwet L77 was used as a negative inoculation control. In each experiment, three plates were used for each line evaluated (Col-0, pSbLTP1.4-GUS-1, pSbLTP1.5-GUS-1). At 3 days post-inoculation (DPI), three plants from each plate were sampled, and GUS histochemical staining was performed. The experiments were repeated three times.

P. syringae inoculations were also performed on adult plants (55 days-old) using the method described by Moriconi et al.77. Shoots were dipped in a bacterial solution (OD600 = 0.7) containing 10 mM MgCl2 and 0.2%Silwet L77 for 30 s. A sterile water solution containing 10 mM MgCl2 and 0.2%Silwet L77 was used as negative control. Three plants of each line evaluated (Col-0, pSbLTP1.4-GUS-1, pSbLTP1.5-GUS-1) were inoculated. At 3 DPI, leaf, inflorescence, and silique samples were taken from each plant, and GUS histochemical staining was performed. The experiments were repeated three times.

Abiotic stress treatments

For osmotic and salt stress assays 10-day-old seedlings grown under normal conditions were transferred to Petri dishes containing MS medium (1/2 MS, 0.7% agar, pH 5.8) supplemented with 0, 100 or 200 mM NaCl and 0, 100 or 200 mM mannitol, respectively. In each experiment, three plates (8 seedlings per plate) were used for each line evaluated (Col-0, pSbLTP1.4-GUS-1, pSbLTP1.4-GUS-2, pSbLTP1.5-GUS-1). After 24 h, three plants were taken from each plate and GUS histochemical staining was performed. The experiments were repeated three times.

Salt stress treatment on adult plants (55 days old) was performed by irrigation with a solution of 0, 100 or 200 mM NaCl. Three plants of each line evaluated (Col-0, pSbLTP1.4-GUS-1, pSbLTP1.5-GUS-1) were used. After 48 h, leaves, inflorescences, and siliques were sampled and, GUS histochemical staining was performed. The experiments were repeated three times.

Histochemical GUS analyses

Plant samples (seedlings, roots, leaves, inflorescences, and siliques) were vacuum infiltrated for 10 min in a solution containing 500 mM Na3PO4, 1mM EDTA pH 8, 0.5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 0.5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100, 0.5% (v/v) N, N-dimethylformamide, and 1mM X-Gluc and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The substrate 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-D-glucuronic acid cyclohexylammonium salt (X-Gluc), used for histochemical GUS staining, was purchased from X-Gluc DIRECT. Following staining, chlorophyll was removed by immersion in 70% ethanol. Plants were then analyzed and photographed using a ZEISS Stemi 2000-C stereomicroscope coupled to a digital camera.

Data availability

The promotor sequences analyzed in this study were retrieved from the publicly available Sorghum bicolor genome (NCBI BioProject ID: PRJNA1387). Detailed information on the genes and their promoter regions is provided in the manuscript.

References

Gichile, H. Review on breeding sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L Moench) for nutritional quality improvement. Int. J. Res. Stud. Agric. 8 (2), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.20431/2454-6224.0802002 (2022).

Blomstedt, C. K. et al. A combined biochemical screen and TILLING approach identifies mutations in Sorghum bicolor L. Moench resulting in acyanogenic forage production. Plant. Biotechnol. J. 10 (1), 54–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00646.x (2012).

Miedaner, T. & Geiger, H. H. Biology, genetics, and management of ergot (Claviceps spp.) in rye, sorghum, and Pearl millet. Toxins 7 (3), 659–678. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins7030659 (2015).

Pyee, J., Yu, H. S. & Kolattukudy, P. E. Identification of a lipid transfer protein as the major protein in the surface wax of broccoli (Brassica oleracea) leaves. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 311 (2), 460–468 (1994).

Pérez-Amador, M. A. et al. Identification of BFN1, a bifunctional nuclease induced during leaf and stem senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant. Physiol. 122, 169–180 (2000).

Missaoui, K. et al. Plant non-specific lipid transfer proteins: an overview. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 171, 115–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.12.026 (2022).

Iqbal, A. et al. Lipid transfer proteins: structure, classification and prospects of genetic engineering for improved disease resistance in plants. PCTOC 153, 3–17 (2023).

Edstam, M. M., Viitanen, L., Salminen, T. A. & Edqvist, J. Evolutionary history of the non-specific lipid transfer proteins. Mol. Plant. 4 (6), 947–964. https://doi.org/10.1093/mp/ssr019 (2011).

Wang, H. W. et al. Insight into the molecular evolution of non-specific lipid transfer proteins via comparative analysis between rice and sorghum. DNA Res. 19 (2), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1093/dnares/dss003 (2012).

Kader, J. C. Lipid-transfer proteins lipid-transfer proteins in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 47 (1), 627–654 (1996).

Duo, J. et al. Genome-wide identification and expression profile under abiotic stress of the barley non-specific lipid transfer protein gene family and its Qingke orthologues. BMC Genom. 22, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-021-07958-8 (2021).

Gittins, J. R. et al. Transgene expression driven by heterologous ribulose-1, 5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase small-subunit gene promoters in the vegetative tissues of Apple (Malus pumila Mill). Planta 210, 232–240 (2000).

Almasia, N. I., Narhirñak, V., Hopp, E. H. & Vazquez-Rovere, C. Isolation and characterization of the tissue and development-specific potato snakin-1 promoter inducible by temperature and wounding. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 13 (5), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.2225/vol13-issue5-fulltext-12 (2010).

Katiyar-Agarwal, S., Agarwal, M. & Grover, A. Emerging trends in agricultural biotechnology research: use of abiotic stress-induced promoter to drive expression of a stress resistance gene in the Transgenic system leads to high level stress tolerance associated with minimal negative effects on growth. Curr. Sci. 77 (12), 1577–1579 (1999).

Kasuga, M., Liu, Q., Miura, S., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. & Shinozaki, K. Improving plant drought, salt, and freezing tolerance by gene transfer of a single stress-inducible transcription factor. Nat. Biotechnol. 17 (3), 287–291 (1999).

Hsieh, T. H., Lee, J. T., Charng, Y. Y. & Chan, M. T. Tomato plants ectopically expressing Arabidopsis CBF1 show enhanced resistance to water deficit stress. Plant. Physiol. 130 (2), 618–626. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.006783 (2002).

Lee, J. T. et al. Expression of Arabidopsis CBF1 regulated by an aba/stress inducible promoter in Transgenic tomato confers stress tolerance without affecting yield. Plant. Cell. Environ. 26 (7), 1181–1190. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.01048.x (2003).

Kasuga, M., Miura, S., Shinozaki, K. & Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. A combination of the Arabidopsis DREB1A gene and stress-Inducible rd29A promoter improved drought-and low-temperature stress tolerance in tobacco by gene transfer. Plant. Cell. Physiol. 45 (3), 346–350 (2004). https://academic.oup.com/pcp/article/45/3/346/1813246

Smirnova, O. G. & Kochetov, A. V. Choice of the promoter for tissue and developmental stage-specific gene expression. Biolistic DNA Delivery Plants: Methods Protocols 96–106 (2020).

Wei, K. & Zhong, X. Non-specific lipid transfer proteins in maize. BMC Plant. Biol. 14, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-014-0281-8 (2014).

Kouidri, A., Whitford, R., Suchecki, R., Kalashyan, E. & Baumann, U. Genome-wide identification and analysis of non-specific lipid transfer proteins in hexaploid wheat. Sci. Rep. 8 (1), 17087. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35375-7 (2018).

José-Estanyol, M., Gomis-Rüth, F. X. & Puigdomènech, P. The eight-cysteine motif, a versatile structure in plant proteins. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 42 (5), 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2004.03.009 (2004).

Fleury, C. et al. Comprehensive classification of the plant non-specific lipid transfer protein superfamily towards its sequence-structure-function analysis. PeerJ 2019 (8). https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.7504 (2019).

Sohal, A. K., Pallas, J. A. & Jenkins, G. I. The promoter of a Brassica napus lipid transfer protein gene is active in a range of tissues and stimulated by light and viral infection in Transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant. Mol. Biol. 41, 75–87 (1999).

Guiderdoni, E. et al. Inducibility by pathogen attack and developmental regulation of the rice Ltp1 gene. Plant. Mol. Biol. 49, 679–695. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015595100145 (2002).

Jung, H. W., Kim, W. & Hwang, B. K. Three pathogen-inducible genes encoding lipid transfer protein from pepper are differentially activated by pathogens, abiotic, and environmental stresses. Plant. Cell. Environ. 26 (6), 915–928. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.01024.x (2003).

Laquitaine, L. et al. Molecular basis of ergosterol-induced protection of grape against Botrytis cinerea: induction of type I LTP promoter activity, WRKY, and Stilbene synthase gene expression. MPMI 19 (10), 1103–1112. https://doi.org/10.1094/MPMI (2006).

Jülke, S. & Ludwig-Müller, J. Response of Arabidopsis thaliana roots with altered lipid transfer protein (LTP) gene expression to the clubroot disease and salt stress. Plants 5 (1), 627–654. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants5010002 (2016).

Gupta, S., Stamatoyannopoulos, J. A., Bailey, T. L. & Noble, W. S. Quantifying similarity between motifs. Genome Biol. 8, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r24 (2007).

Bailey, T. L., Johnson, J., Grant, C. E. & Noble, W. S. The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (1), 39–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv416 (2015).

Shi, L. et al. AtMYB31 is a wax regulator associated with reproductive development in Arabidopsis. Planta 256 (2), 28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-022-03945-9 (2022).

Ramírez, V., García-Andrade, J. & Vera, P. Enhanced disease resistance to botrytis cinerea in myb46 Arabidopsis plants is associated to an early downregulation of CesA genes. Plant. Signal. Behav. 6 (6), 911–913. https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.6.6.15354 (2011).

Gao, Y. et al. BjMYB1, a transcription factor implicated in plant defence through activating BjCHI1 chitinase expression by binding to a W-box-like element. J. Exp. Bot. 67 (15), 4647–4658. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erw240 (2016).

Zhao, Y. et al. The wheat MYB transcription factor TaMYB31 is involved in drought stress responses in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant. Sci. 9, 1426 (2018).

Zhang, P. et al. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor AtMYB49 modulates salt tolerance in Arabidopsis by modulating the cuticle formation and antioxidant defence. Plant. Cell. Environ. 43 (8), 1925–1943. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.13784 (2020).

Pelayo, M. A., Yamaguchi, N. & Ito, T. One factor, many systems: the floral homeotic protein AGAMOUS and its epigenetic regulatory mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Plant. Biol. 61, 102009. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2021.102009 (2021).

Zhou, Y., Zhou, W., Liu, H., Liu, P. & Li, Z. Genome-wide analysis of the soybean DREB gene family: identification, genomic organization and expression profiles in response to drought stress. Plant. Breed. 139 (6), 1158–1167. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbr.12867 (2020).

Sakuma, Y. et al. DNA-binding specificity of the ERF/AP2 domain of Arabidopsis drebs, transcription factors involved in dehydration- and cold-inducible gene expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 290 (3), 998–1009. https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.2001.6299 (2002).

Lim, C. J. et al. Gene expression profiles during heat acclimation in Arabidopsis thaliana suspension-culture cells. J. Plant. Res. 119 (4), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-006-0285-z (2006).

Nakano, T., Suzuki, K., Fujimura, T. & Shinshi, H. Genome-wide analysis of the ERF gene family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant. Physiol. 140 (2), 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.105.073783 (2006).

Sharma, M. K. et al. Identification, phylogeny, and transcript profiling of ERF family genes during development and abiotic stress treatments in tomato. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 284 (6), 455–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00438-010-0580-1 (2010).

Lee, S., Lee, S. & Kim, S. Y. AtERF15 is a positive regulator of ABA response. Plant. Cell. Rep. 34, 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-014-1688-2 (2015).

Carbonero, P., Iglesias-Fernández, R. & Vicente-Carbajosa, J. The AFL subfamily of B3 transcription factors: evolution and function in angiosperm seeds. J. Exp. Bot. 68 (4), 871–880. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erw458 (2017).

Tamminen, I., Mäkelä, P., Heino, P. & Palva, E. T. Ectopic expression of ABI3 gene enhances freezing tolerance in response to abscisic acid and low temperature in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant. J. 25 (1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313x.2001.00927.x (2001).

Khandelwal, A. et al. Role of ABA and ABI3 in desiccation tolerance. Science 327 (5965), 546–546. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1183672 (2010).

Bedi, S. & Nag Chaudhuri, R. Transcription factor ABI3 auto-activates its own expression during dehydration stress response. FEBS Lett. 592 (15), 2594–2611. https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.13194 (2018).

Bedi, S., Sengupta, S., Ray, A. & Nag Chaudhuri, R. ABI3 mediates dehydration stress recovery response in Arabidopsis thaliana by regulating expression of downstream genes. Plant. Sci. 250, 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.06.006 (2016).

Sengupta, S., Ray, A., Mandal, D. & Nag Chaudhuri, R. ABI3 mediated repression of RAV1 gene expression promotes efficient dehydration stress response in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 1863 (9), 194582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagrm.2020.194582 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Liu, X., Zhang, K., Zhang, D. & Guan, K. An ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE3-like gene from the desert moss Syntrichia caninervis confers abiotic stress tolerance and reduces ABA sensitivity. Plant. Cell. Tiss Org. 133 (3), 417–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11240-018-1394-9 (2018).

Chiu, R. S., Nahal, H., Provart, N. J. & Gazzarrini, S. The role of the Arabidopsis FUSCA3 transcription factor during Inhibition of seed germination at high temperature. BMC Plant. Biol. 12, 1–16 (2012).

Blaney, B. J. et al. Sorghum ergot (Claviceps africana) associated with agalactia and feed refusal in pigs and dairy cattle. Aust Vet. J. 78 (2), 102–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-0813.2000.tb10535.x (2000).

Salminen, T. A., Blomqvist, K. & Edqvist, J. Lipid transfer proteins: classification, nomenclature, structure, and function. Planta 244 (5), 971–997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-016-2585-4 (2016).

Zhang, M. et al. Genome-wide analysis of the barley non-specific lipid transfer protein gene family. Crop J. 7 (1), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cj.2018.07.009 (2019).

Xue, Y. et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of Nsltp gene family in rapeseed (Brassica napus) reveals their critical roles in biotic and abiotic stress responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (15), 8372. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158372 (2022).

Dong, X. et al. Genome-wide identification of common bean PvLTP family genes and expression profiling analysis in response to drought stress. Genes 13 (12). https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13122394 (2022).

Vangelisti, A. et al. In Silico genome-wide characterisation of the lipid transfer protein Multigenic family in sunflower (H. annuus L). Plants 11 (5), 664. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11050664 (2022).

Edqvist, J., Blomqvist, K., Nieuwland, J. & Salminen, T. A. Plant lipid transfer proteins: are we finally closing in on the roles of these enigmatic proteins? J. Lipid Res. 59 (8), 1374–1382. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.R083139 (2018).

Xu, Z. S., Chen, M., Li, L. C. & Ma, Y. Z. Functions and application of the AP2/ERF transcription factor family in crop improvement. J. Integr. Plant. Biol. 53 (7), 570–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7909.2011.01062.x (2011).

Ito, Y. et al. Functional analysis of rice DREB1/CBF-type transcription factors involved in cold-responsive gene expression in Transgenic rice. Plant. Cell. Physiol. 47 (1), 141–153. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pci230 (2006).

Li, F. et al. Genome-wide identification, molecular evolution and expression analysis of the non-specific lipid transfer protein (nsLTP) family in Setaria italica. BMC Plant. Biol. 22 (1), 547 (2022).

Mergaert, P. Role of antimicrobial peptides in controlling symbiotic bacterial populations. Nat. Prod. Rep. 35 (4), 336–356. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7NP00056A (2018).

Weinhold, A., Karimi Dorcheh, E., Li, R., Rameshkumar, N. & Baldwin, I. T. Antimicrobial peptide expression in a wild tobacco plant reveals the limits of host-microbe-manipulations. Field Elife. 7, e28715. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.28715 (2018).

Turner, T. R. et al. Comparative metatranscriptomics reveals Kingdom level changes in the rhizosphere Microbiome of plants. ISME J. 7 (12), 2248–2258. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2013.119 (2013).

Berg, G., Grube, M., Schloter, M. & Smalla, K. Unraveling the plant microbiome: looking back and future perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 5, 148. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2014.00148 (2014).

Purahong, W. et al. First insights into the Microbiome of a Mangrove tree reveal significant differences in taxonomic and functional composition among plant and soil compartments. Microorganisms 7 (12), 585. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms7120585 (2019).

Finn, R. D. et al. HMMER web server: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (1), 30–38 (2015).

Armenteros, J. J. A. et al. Detecting sequence signals in targeting peptides using deep learning. Life Sci. Alliance 2(5). (2019).

Eisenhaber, B. et al. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol lipid anchoring of plant proteins. Sensitive prediction from sequence- and genome-wide studies for Arabidopsis and rice. Plant. Physiol. 133 (4). https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.103.023580 (2003). ,1691 – 701.

Duvaud, S. et al. Expasy, the Swiss bioinformatics resource portal, as designed by its users. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 216–227. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkab225 (2021).

Waterhouse, A. M., Procter, J. B., Martin, D. M., Clamp, M. & Barton, G. J. Jalview version 2—a multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 25 (9), 1189–1191. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp033 (2009).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37 (5), 1530–1534. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa015 (2020).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 52 (5), 78–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae268 (2024).

Kong, X. et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of expression profiles of maize mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase. PLoS ONE. 8 (2), e57714. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0057714 (2013).

Di Tommaso, P. et al. T-Coffee: a web server for the multiple sequence alignment of protein and RNA sequences using structural information and homology extension. Nucleic Acids Res. 39 (2), 13–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr245 (2011).

Stothard, P. The sequence manipulation suite: javascript programs for analyzing and formatting protein and DNA sequences. Biotechniques 28 (6), 1102–1104. https://doi.org/10.2144/00286ir01 (2000).

Hruz, T. et al. Genevestigator V3: A reference expression database for the meta-analysis of transcriptomes. Adv. Bioinf. 2008, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2008/420747 (2008).

Moriconi, V. et al. LOV-domain photoreceptor, encoded in a genomic island, attenuates the virulence of Pseudomonas syringae in light-exposed Arabidopsis leaves. Plant. J. 76 (2), 322–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.12289 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We express our appreciation to Andrea Dengis for the technical support and for the maintenance of the plants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AMZ conceived and supervised research. LAC, AEM and LM designed and performed the experiments. LAC, AEM and LM analyzed the in silico data. AMZ, AEM and LM wrote the manuscript. AMZ, LAC, LM, AEM and GES reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cossio, L.A., Melgar, A.E., Moyano, L. et al. Genome-wide identification of lipid transfer proteins in Sorghum bicolor and discovery of flower-specific promoters. Sci Rep 15, 25710 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08625-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08625-8