Abstract

This randomized controlled trial investigated the effects of a spiritual care program on the sleep quality of 95 patients undergoing hemodialysis in Iran. Participants from Shahid Beheshti Hospital, Hamadan, were randomly assigned to either the experimental (N = 48) or control (N = 47) group. The intervention comprised six sessions (two sessions of 45–60 min per week) and encompassed spiritual needs assessment, religious, psychological, supportive, and spiritual care, as well as evaluation. Sleep quality was measured using the Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI), with scores > 5 indicating poor sleep, at baseline, one month, and two months post-intervention. At the two-month follow-up, a significant between-group difference was observed in overall sleep quality and its dimensions (P < 0.05). The experimental group demonstrated a significant improvement in sleep quality from baseline to two months post-intervention (P < 0.001), whereas the control group exhibited a decline (P < 0.05). These findings underscore the significance of incorporating spiritual care into nursing practice to enhance sleep quality in patients undergoing hemodialysis.

Trial registration: (Clinical trial registration code: IRCT20160110025929N41 and date: 11/11/2022).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

People living with kidney failure require hemodialysis to survive; however, this treatment is often accompanied by numerous physical and psychological challenges that can negatively impact their quality of life1. One of the common problems of these patients is poor sleep quality, which is an important aspect of their well-being, as it affects their physical, mental, and emotional health2,3. However, many of these patients suffer from poor sleep quality due to various factors such as dialysis schedule, dialysis duration, dialysis adequacy, presence of co-morbidities, and psychological distress caused by chronic and life-threatening conditions1,3.

A recent systematic review indicates that the prevalence of poor sleep quality among individuals with chronic kidney disease (CKD) is 59% in those not receiving replacement therapy, and ranges from 67 to 68% in patients undergoing dialysis4. Also, in Iran, the prevalence of sleep disorders in these patients is 78.2%5. Poor sleep quality can lead to fatigue, depression, impaired cognitive function, decreased hope, decreased spiritual health, and increased risk of mortality in the long term. Improving sleep quality is a crucial objective for both hemodialysis patients and their healthcare providers, particularly nurses6.

Various methods have been used to improve the sleep quality of these patients, including pharmacologic treatments (such as melatonin or benzodiazepines), non-pharmacologic treatments (such as cognitive-behavioral therapy or relaxation techniques), or changes related to dialysis (such as changing the dialysis program or dialysis combination)7,8. However, besides these interventions, less attention has been paid to the spiritual dimension and spiritual health9. Research has shown that hemodialysis patients’ sleep quality and spiritual health are related. Therefore, it seems that the sleep quality of these patients can be improved by strengthening spiritual health through spiritual care10,11.

Spiritual care is a holistic approach that addresses patients’ spiritual needs and well-being, especially those suffering from chronic or terminal illnesses12,13,14. Spiritual care can include various activities such as prayer, meditation, reading religious texts, listening to music, or engaging in meaningful conversations. Spiritual care can help patients cope with their illness, find meaning and purpose in life, and experience peace and hope15. Also, spiritual care can have a positive effect on chronic patients by reducing stress, anxiety, depression, and pain and by increasing relaxation, comfort, and satisfaction15,16,17.

Nevertheless, providing spiritual care to chronic patients, including those undergoing hemodialysis, has its limitations and challenges. One major obstacle is the lack of agreement on defining and evaluating spirituality and its various components, such as the meaning of life and peace. Various instruments may focus on different aspects of spirituality, which may not align with some patients’ cultural or religious beliefs18,19,20. The second major issue that needs to be addressed is the lack of standardized protocols and guidelines for spiritual care for hemodialysis patients. The type, frequency, and duration of spiritual care may vary depending on patients’ preferences and individual needs21,22. Third, there may be barriers to implementing spiritual care in the clinical setting, such as time constraints, lack of training and resources, ethical issues, and personal beliefs of healthcare providers23.

Therefore, more research is needed to determine the optimal method of spiritual care for hemodialysis patients and evaluate its long-term effects on their sleep quality. In addition, when providing spiritual care to hemodialysis patients, the role of individual factors such as religiosity, spirituality, culture, and preferences should be considered. Few studies have addressed this issue21,24,25,26,27. Therefore, this seems to be a gap and deficiency in nursing that requires extensive research. The present study investigated the effect of a spiritual care program on the sleep quality of hemodialysis patients in Iran.

Methods

Study design

The present study employed a randomized controlled trial design, comprising an experimental group and a control group. The study involved 95 hemodialysis patients referred to the Shahid Beheshti Hospital’s dialysis center in Hamadan, Iran. The study was conducted from November 2022 to September 2023.

The sample selection criteria

The inclusion criteria were: having a definitive diagnosis of kidney failure and currently undergoing hemodialysis, confirmed by a nephrology specialist, being a Muslim, having access to a smartphone, having the cognitive ability and physical stability to participate in the intervention sessions and complete the study questionnaires, not having confirmed mental disorders, not having other debilitating diseases, having minimum reading and writing literacy, not having known vision and hearing problems, not having cognitive problems such as Alzheimer’s, being able to communicate verbally, scoring higher than 5 on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and accepting spiritual care. The exclusion criteria were dying during the study, and missing more than one spiritual care session.

Sample size calculation

The sample size was determined based on a previous study by Vazifehdoost Nezami et al.28considering a 95% confidence level (α = 0.05), 80% test power (1 − β = 0.80), an effect size (d = 0.603), and an anticipated 10% attrition rate. Using G*Power version 3.1 software, the required sample size was estimated at 50 participants per group, totaling 100 participants (Fig. 1).

Sampling and random allocation method

First, a list of all hemodialysis patients was prepared from the health technology unit of the hospital as a sampling frame by the researcher. After checking the list of patients and excluding those who did not meet the study criteria, the hospital’s hemodialysis departments (halls A, B, C) were visited. All patients were screened for eligibility, and the final list was prepared. For all the patients who came for hemodialysis, mainly in the morning shift, the study’s objectives, the intervention method, the randomization method, and the necessary information regarding the voluntary nature of participation in the study were explained, and written informed consent was obtained from them. Convenience sampling was used to select the samples based on the inclusion criteria.

Random allocation was performed using the permuted block method by the third author. In this way, 25 blocks of ABBA, AABB, ABAB, BBAA, BAAB, and BABA were generated and placed in envelopes (letter A: experimental group and letter B: control group). Then, when the patients entered the study, one of the envelopes was randomly selected, and the first four patients were assigned to two groups according to the selected block. This process continued until the completion of the total number of samples.

To prevent contamination bias between the intervention and control groups, participants were physically separated and assigned to different halls based on their group allocation, with the coordination of the dialysis department officials. The experimental group was in hall A, and the control group was in halls B and C (according to the patients’ preferences). These halls were completely separated, and the experimental group was told not to disclose any information about the sessions to the control group.

Data collection tool

Demographic information form

The demographic questionnaire included personal characteristics such as age, gender, economic status, level of education, level of family support, and level of religious activity (all self-reported), as well as duration of diagnosis and frequency of hemodialysis per week (obtained from medical records). This form was reviewed, revised and approved by ten faculty members of Hamadan School of Nursing.

Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI)

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to assess sleep quality over the past month. It includes 9 items that evaluate 7 components: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. Each component is scored from 0 (no difficulty) to 3 (severe difficulty), with a total score ranging from 0 to 21; scores > 5 indicate poor sleep quality. The PSQI was originally developed by Buysse et al. (1989), demonstrating strong psychometric properties (sensitivity: 89.6%, specificity: 86.5%, reliability: r = 0.88)29. Its validity and reliability have been confirmed in Iranian studies by Hosseinabadi et al. (r = 0.88) and Soleimani et al. (r = 0.84)30,31. In the present study, the internal consistency of the PSQI was confirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90.

Intervention and procedure

The experimental group received a culturally tailored spiritual care program, whereas the control group received the usual care provided in the hemodialysis department. Usual care includes routine dialysis sessions, monitoring of vital signs and lab values, management of underlying conditions, basic patient education, and general nursing care. While psychosocial support may be offered, it is not delivered in a structured or standardized format.

The spiritual care program followed a standardized localization method. To develop the spiritual care intervention, we adopted a structured localization process based on international spiritual care guidelines, adapted specifically for Iranian patients. The methodology consisted of six sequential components: (1) assessing spiritual needs, (2) providing religious support, (3) delivering spiritual care, (4) offering psychological-spiritual support, (5) sustaining spiritual engagement, and (6) evaluating care outcomes32. This method was tailored to the spiritual needs of Iranian patients, aligning with international guidelines and local practices, with input from Iranian healthcare experts. The goal was to provide spiritual care services to support chronic patients33.

The selection of specific content for the spiritual care intervention was grounded in a culture-based and context-sensitive approach appropriate to the Iranian healthcare environment. Accordingly, prior to the main study, a pilot study was conducted to ensure cultural sensitivity and contextual relevance. This study involved ten hemodialysis patients of varying ages, genders, and durations of treatment (informed written consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment). The pilot phase aimed to explore spiritual concerns from the participants’ perspectives and to test the content and primary care questions.

Concurrently, existing literature on the spiritual needs of hemodialysis and other chronic patients was reviewed. The insights obtained from this pilot design were complemented by findings from the literature on spiritual needs in chronic diseases. Based on these data, an initial draft of the spiritual care program was developed and subsequently reviewed, revised, and refined by a multidisciplinary panel comprising nursing faculty members, a religious counselor familiar with Islamic teachings, a psychologist, a nephrologist, and dialysis nurses.

Key modifications and components adjusted to the original framework of the spiritual care program included:

-

Incorporating Islamic concepts and practices consistent with Iranian Shia beliefs,

-

Using language, phrases, and metaphors familiar to Iranian culture,

-

Structuring discussions to reflect communication norms in Iranian society,

-

Incorporating audiovisual resources appropriate for the local population,

-

Providing referrals to religious or psychological professionals as needed.

These modifications ensured that the intervention was both culturally grounded and clinically applicable in the Iranian healthcare setting.

In the next step, the same ten patients participated in a pilot study consisting of six initial spiritual care sessions, which helped refine the program. The adjusted components were evaluated and adapted during this pilot phase prior to their inclusion in the main study. It should be noted that the participants in the pilot study (n = 10) were not included in the main study sample. Their participation was limited to assisting in the refinement and development of the program, procedures, and study instruments (Fig. 2).

Subsequently, the finalized intervention-six sessions of spiritual care (two per week, 45–60 min each)—was implemented for each participant in the experimental group at Beheshti Hospital, Hamadan, during their dialysis sessions in the morning shift by the first author (refer to Table 1). Sessions were supervised by a PhD in medical-surgical nursing (the third author). Participants were referred to or connected with a religious counselor, psychologist, or nephrologist as needed.

To reinforce learning, a 15–20-minute video related to each session was shared via smartphone, and participants were encouraged to integrate the practices into their daily lives. The researcher provided ongoing support via phone and contacted participants between sessions to address questions or concerns.

The control group received only current and conventional nursing care. Evaluation of sleep quality after spiritual care intervention was done one month and two months after the last care session13. The researcher guided them in resolving any ambiguity related to the questionnaire questions by being present at their bedside and supervising the completion of the questionnaire.

Relevant guidelines and regulations

The present study was conducted under the supervision and approval of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences. In accordance with the ethical guidelines established by this institution, all human research must adhere to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Consequently, this study was implemented in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, which serves as a foundational document for ethical medical research involving human subjects.

Data analysis method

All the data were entered into SPSS version 16 software for analysis after collection. Quantitative variables were described using the mean and standard deviation, and qualitative variables were described using the frequency and percentage. The normality assumption of quantitative variables was tested using Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Chi-square tests, Fisher’s exact test, and independent t-test were used to compare the characteristics of the experimental and control groups. Independent t-test was used to compare the sleep quality scores between groups and repeated measures ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post hoc test were used to compare the sleep quality scores within groups. The significance level in this study was set at less than 0.05.

Results

At baseline, the socio-demographic variables of the hemodialysis patients who participated in this study were not significantly different between the groups, indicating that the groups were similar (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

At baseline, there was no significant difference between the groups in the mean scores of sleep quality and its dimensions among hemodialysis patients (P > 0.05), but one month and two months after the intervention, this difference was significant (P < 0.05). In the experimental group, from baseline to two months after the intervention (within-group difference), there was a significant decrease in the mean scores of sleep quality and its dimensions (P < 0.001). However, in the control group, from baseline to two months after the intervention (within-group difference), there was a significant increase in the mean score of sleep quality (P = 0.008) and some of its dimensions such as subjective sleep quality (P = 0.001), sleep latency (P = 0.001), sleep duration (P = 0.001) and sleep efficiency (P = 0.007) (Table 3).

Discussion

The present study examined the effect of a spiritual care program on the sleep quality of Iranian hemodialysis patients. The results showed that the average sleep quality score of the intervention group decreased after receiving the spiritual care program compared to the control group. This indicates an improvement in sleep quality in the intervention group.

The results of previous studies on chronic patients are consistent with our study. Motavakel et al. (2020) found that providing spiritual care improved the sleep quality of multiple sclerosis patients34. Vazifehdoost Nezami et al. (2021) reported that implementing spiritual care for patients with post-traumatic stress disorder improved their sleep quality28. Yousofvand et al. (2023) observed that the sleep quality of stroke patients improved after receiving spiritual care13.

The present study’s results were inconsistent with the results of Yang et al. (2008). They found that the total scores of religious and spiritual activities were not correlated with the global score of PSQI in hemodialysis patients, but they were related to different components of sleep quality35. The reasons for this inconsistency could be differences in the study method, religious, cultural and social background. Their study was correlational and had less control, while ours was a clinical trial with high control. In terms of the cultural-religious-social background, Iranian people engage in religious and spiritual activities to a great extent and it is part of their daily activities, as shown by various studies in Iran14,36. Yang et al. (2008) also noted that patients who had strong “spiritual” beliefs reported more problems in “sleep disturbance”, while those who strongly practiced religious beliefs reported fewer problems in “daytime functioning”35. However, Hill et al. (2018) found that religious intervention effectively improved the patient’s sleep quality and suggested that some activities, such as believing in divine support and attending ceremonies and places, directly and indirectly affected sleep37.

In hemodialysis patients, sleep disorders seem to be related to disease complications, medications, depression, anxiety, and movement limitations. In their research, Benetou et al. (2022) found a significant correlation between insomnia and various factors among hemodialysis patients. These factors included the patient’s age, co-morbidities, fatigue, changes in body appearance, itching, and clothing restrictions. The poor sleep quality experienced by these patients posed numerous challenges, necessitating the identification of factors influencing sleep quality and the development of suitable interventions38.

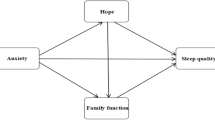

In the present study, compared to the control group, patients in the intervention group experienced improved sleep quality after receiving the spiritual care program. This could be because spiritual care is a type of comprehensive care that addresses the spiritual needs and well-being of patients with chronic or incurable diseases, such as hemodialysis patients. Spiritual care may have improved the sleep quality of hemodialysis patients due to several features. First, creating a sense of meaning and purpose in their lives could reduce their anxiety and depression. Furthermore, offering assistance to individuals in managing the physical, emotional, and social difficulties associated with their condition has the potential to enhance their resilience and self-esteem. Additionally, providing a sense of hope and tranquility can bolster their positive emotions and overall satisfaction with life. Fourth, supporting them in religious or spiritual beliefs and practices could strengthen their faith and connection with a higher power21,23,39.

In general, spiritual care can help patients cope with their illness, find meaning and purpose in life, and experience peace and hope. Furthermore, spiritual care can potentially enhance the well-being of chronic patients. It can alleviate stress, anxiety, depression, and pain while promoting relaxation, comfort, and satisfaction. Consequently, this holistic approach can contribute to enhancing the quality of their sleep13,40.

The findings of this study have important practical implications for improving the quality of life among hemodialysis patients. Sleep quality, as a vital component of overall well-being, is closely linked to patients’ physical and mental health, as well as their adherence to treatment regimens. Given this connection, it is crucial for healthcare providers—particularly nurses who often have the most direct and sustained contact with these patients—to systematically assess and address the spiritual needs of individuals undergoing hemodialysis.

Integrating spiritual care into routine practice can be a valuable strategy to enhance sleep quality. Interventions such as individual or group counseling, guided prayer or meditation, music therapy, and art-based therapies can be tailored to patients’ beliefs and preferences, providing emotional comfort, reducing anxiety, and promoting relaxation. These approaches not only support better sleep but also contribute to improved coping mechanisms, reduced depressive symptoms, and enhanced patient satisfaction. Therefore, healthcare systems are recommended to prioritize training nurses in spiritual care competencies and developing protocols that incorporate holistic, patient-centered strategies aimed at improving sleep and overall health outcomes in this vulnerable population.

It is noted that, although the study was conducted within a specific Iranian sociocultural and religious context, its findings hold potential value beyond this setting. The universal human needs for meaning, comfort, and emotional-spiritual support are not limited to one culture. With appropriate cultural adaptations, the core framework of the spiritual care program—assessing needs, providing structured support, and involving interdisciplinary collaboration—can be applied in other geographic and cultural contexts. Clinically, this study provides a practical model for integrating spiritual care into chronic disease management. The approach supports holistic nursing practice and may enhance patients’ quality of life, reduce distress, and improve adherence. Multicenter and cross-cultural studies are recommended to validate and refine this model in broader populations.

Conclusion

The present study’s findings suggest that implementing the spiritual care program can improve the sleep quality of hemodialysis patients. Therefore, it is recommended that healthcare providers, especially nurses, pay attention to the spiritual needs of these patients and provide them with spiritual care based on their needs. By doing so, they can take an important step in enhancing the sleep of these patients. The nursing education system is also recommended to focus on training spiritual care implementation for nursing students. so that, they can incorporate it into the holistic nursing care program in the future.

Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the findings. First, the use of self-reported measures for assessing sleep quality may have introduced response bias, which could affect the validity of the results. Future research should incorporate objective sleep assessment tools such as actigraphy or polysomnography to provide more reliable data. Second, participant fatigue due to prolonged bed rest during dialysis sessions may have influenced their responses and engagement with the intervention. Although rest breaks were provided, future studies might consider scheduling interventions during less physically demanding times or using shorter and more flexible sessions to improve participation. Third, logistical challenges related to scheduling conflicts between nurses’ duties and the delivery of the spiritual care program limited intervention implementation. Enhanced collaboration with clinical staff and integration of the intervention into routine dialysis workflows could improve feasibility in future research. Finally, the relatively short follow-up period restricted evaluation of the long-term effects of spiritual care on sleep quality. It is recommended that future studies employ longer follow-up durations (six months or more) to better understand the sustained impact of such interventions on sleep and overall well-being in hemodialysis patients.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to keeping participants’ information confidential but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Dembowska, E., Jaroń, A., Gabrysz-Trybek, E. & Bladowska, J. Quality of life in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing hemodialysis. J. Clin. Med. 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11061584 (2022).

Scott, A. J., Webb, T. L., Martyn-St James, M., Rowse, G. & Weich, S. Improving sleep quality leads to better mental health: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep. Med. Rev. 60, 101556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101556 (2021).

Alshammari, B. et al. Sleep quality and its affecting factors among Hemodialysis patients: A multicenter Cross-Sectional study. Healthc. (Basel). 11 https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11182536 (2023).

Tan, L. H. et al. Insomnia and poor sleep in CKD: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Kidney Med. 4, 100458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xkme.2022.100458 (2022).

Hosseini, M., Nasrabadi, M., Mollanoroozy, E. & Khani, F. Relationship of sleep duration and sleep quality with health-related quality of life in patients on Hemodialysis in Neyshabur. Sleep. Medicine: X. 5, 100064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleepx.2023.100064 (2023).

Kalantar-Zadeh, K., Lockwood, M. B., Rhee, C. M. & Tantisattamo, E. Patient-centred approaches for the management of unpleasant symptoms in kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 18, 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41581-021-00518-z (2022).

Yang, B. et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for improving sleep quality in patients on dialysis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. Rev. 23, 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2014.11.005 (2015).

Natale, P., Ruospo, M., Saglimbene, V. M., Palmer, S. C. & Strippoli, G. F. Interventions for improving sleep quality in people with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 5 (Cd012625). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012625.pub2 (2019).

Natale, P., Ruospo, M., Saglimbene, V. M. & Palmer, S. C. Interventions for improving sleep quality in people with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 5 (Cd012625) https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012625.pub2 (2019).

Bagheri, H., Sadeghi, M., Esmaeili, N. & Naeimi, Z. Relationship between spiritual health and depression and quality of sleep in the older adults in shahroud. J. Gerontol. 1, 55–62. https://doi.org/10.18869/acadpub.joge.1.1.71 (2016).

Eslami, A. A., Rabiei, L., Khayri, F. & Rashidi Nooshabadi, M. R. Sleep quality and spiritual well-being in Hemodialysis patients. Iran. Red Crescent Med. J. 16, e17155. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.17155 (2014).

Safarabadi, M., Yousofvand, V., Jadidi, A., Dehghani, S. M. T. & Ghaffari, K. The relationship between spiritual health and quality of life among COVID-19 patients with long-term complications in the post-coronavirus era. Front. Public. Health 12 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1371110 (2024).

Yousofvand, V., Torabi, M., Oshvandi, K. & Kazemi, S. Impact of a spiritual care program on the sleep quality and spiritual health of Muslim stroke patients: A randomized controlled trial. Complement. Ther. Med. 77, 102981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2023.102981 (2023).

Jadidi, A., Sadeghian, E., Khodaveisi, M. & Fallahi-Khoshknab, M. Spiritual needs of the Muslim elderly living in nursing homes: A qualitative study. J. Relig. Health. 61, 1514–1528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01263-0 (2022).

Oshvandi, K., Torabi, M., Khazaei, M., Khazaei, S. & Yousofvand, V. Impact of hope on stroke patients receiving a spiritual care program in iran: A randomized controlled trial. J. Relig. Health. 63, 356–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01696-1 (2024).

Torabi, M., Yousofvand, V., Mohammadi, R. & Karbin, F. Effectiveness of group spiritual care on leukemia patients’ hope and anxiety in iran: A randomized controlled trial. J. Relig. Health. 63, 1413–1432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-023-01866-9 (2024).

Khalili, Z., Habibi, E., Kamyari, N., Tohidi, S. & Yousofvand, V. Correlation between spiritual health, anxiety, and sleep quality among cancer patients. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 20, 100668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijans.2024.100668 (2024).

Rahimpour, M., Parizad, N., khorrami markani, A. & Alinejad, V. The effect of spiritual care program on treatment adherence of patients undergoing Hemodialysis. Nurs. Midwifery J. 22, 38–48. https://doi.org/10.61186/unmf.22.1.38 (2024).

Clark, M. & Emerson, A. Spirituality in psychiatric nursing: A concept analysis. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurses Assoc. 27, 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390320902834 (2021).

Hartiti, T., Silfiyani, L. D., Rejeki, S., Pohan, V. Y. & Yanto, A. Relationship of spiritual caring with quality of live for Hemodialysis patients: A literature review. Open. Access. Macedonian J. Med. Sci. 9, 85–89. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2021.7835 (2022).

Oshvandi, K., Amini, S., Moghimbeigi, A. & Sadeghian, E. The effect of a spiritual care on hope in patients undergoing hemodialysis: A randomized controlled trial. Curr. Psychiatry Res. Reviews Formerly: Curr. Psychiatry Reviews. 16, 68–75. https://doi.org/10.2174/2666082216666200316142803 (2020).

de Diego-Cordero, R., Suárez-Reina, P., Badanta, B., Lucchetti, G. & Vega-Escaño, J. The efficacy of religious and spiritual interventions in nursing care to promote mental, physical and spiritual health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appl. Nurs. Res. 67, 151618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2022.151618 (2022).

Fradelos, E. C., Alikari, V., Tsaras, K. & Papathanasiou, I. V. The effect of spirituality in quality of life of Hemodialysis patients. J. Relig. Health. 61, 2029–2040. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01153-x (2022).

Saedi, F. et al. Predictive role of spiritual health, resilience, and mental well-being in treatment adherence among Hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 25, 326. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12882-024-03768-8 (2024).

Bravin, A. M., Trettene, A. S., Andrade, L. G. M. & Popim, R. C. Benefits of spirituality and/or religiosity in patients with chronic kidney disease: an integrative review. Revista Brasileira De Enfermagem. 72, 541–551. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2018-0051 (2019).

Asadzandi, M., Mazandarani, H. A., Saffari, M. & Khaghanizadeh, M. Effect of spiritual care based on the sound heart model on spiritual experiences of Hemodialysis patients. J. Relig. Health. 61, 2056–2071. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01396-2 (2022).

Durmuş, M. & Ekinci, M. The effect of spiritual care on anxiety and depression level in patients receiving Hemodialysis treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J. Relig. Health. 61, 2041–2055. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01386-4 (2022).

Vazifehdoost nezami, M., Khaloobagheri, E., Sadeghi, M. & Hojjati, H. Effect of spiritual care based on pure soul (Heart) on sleep quality Post-Traumatic stress disorder. Military Caring Sci. 7, 301–309. https://doi.org/10.52547/mcs.7.4.301 (2021).

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., Kupfer, D. J. & rd, & The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 28, 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 (1989).

Hossein-Abadi, R., Nowrouzi, K., Pouresmaili, R., Karimloo, M. & Maddah, S. S. B. Acupoint massage in improving sleep quality of older adults. Archives Rehabilitation. 9, 8–14 (2008).

Soleimany, M., Ziba, F. N., Kermani, A. & Hosseini, F. Comparison of sleep quality in two groups of nurses with and without rotation work shift hours. Iran. J. Nurs. 20, 29–38 (2007).

Collaboration, A. The ADAPTE Manual and resource toolkit for guidelne adaptation. 2.0 v, (2010).

Irajpour, A., Moghimian, M. & Arzani, H. 3 Interprofessional Clinical Guideline: Spiritual Care for Chronic Patients: Esfahan University of Medical Sciences (Esfahan University of Medical Sciences, 2020).

Motavakel, N., Maghsoudi, Z., Mohammadi, Y. & Oshvandi, K. The effect of spiritual care on sleep quality in patients with multiple sclerosis referred to the MS society of Hamadan City in 2018. Avicenna J. Nurs. Midwifery Care. 28, 36–45. https://doi.org/10.30699/ajnmc.28.1.36 (2020).

Yang, J. Y., Huang, J. W., Kao, T. W. & Peng, Y. S. Impact of spiritual and religious activity on quality of sleep in Hemodialysis patients. Blood Purif. 26, 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1159/000118845 (2008).

Jadidi, A., Khodaveisi, M., Sadeghian, E. & Fallahi-Khoshknab, M. Exploring the process of spiritual health of the elderly living in nursing homes: A grounded theory study. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 31 https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhs.v31i3.16 (2021).

Hill, T. D., Deangelis, R. & Ellison, C. G. Religious involvement as a social determinant of sleep: an initial review and conceptual model. Sleep. Health. 4, 325–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleh.2018.04.001 (2018).

Benetou, S., Alikari, V., Vasilopoulos, G. & Polikandrioti, M. Factors associated with insomnia in patients undergoing Hemodialysis. Cureus 14, e22197. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.22197 (2022).

Burlacu, A., Artene, B., Nistor, I. & Buju, S. Religiosity, spirituality and quality of life of dialysis patients: a systematic review. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 51, 839–850. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-019-02129-x (2019).

Torabi, M., Yousofvand, V., Azizi, A. & Kamyari, N. Impact of spiritual care programs on stroke patients’ death anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. J. Affect. Disorders Rep. 14, 100650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2023.100650 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This article is part of a larger study. This article is the result of a research project approved by the Hamadan University of Medical Sciences as provided the funding (project number: 140207045342 and ethical code: IR.UMSHA.REC.1401.626). The authors express their gratitude to all the patients who participated in the study, their caregivers, and the nurses of the hemodialysis departments.

Funding

A grant for this study was provided by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (Grant Number: 140207045342).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. Vahid Yousofvand was responsible for designing, conducting the research, writing and submitting the manuscript. Naser Kamyari was involved in analyzing the data and writing the manuscript. Mohammad Torabi was in charge of designing and conducting the research, writing and submitting the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The present study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (ethics code: IR.UMSHA.REC.1401.626, clinical trial registration center code: IRCT20160110025929N41 and date: 11/11/2022). The patients were given full information about how to conduct the study. All participants signed informed written consent before participating in the study and publishing the results. After the completion of the study, to comply with the ethical principles in research, the control group was also provided with the recorded clips and pamphlets containing spiritual care and care of hemodialysis patients.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

The authors affirm that the participants gave their written informed consent to participate and publish the results.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yousofvand, V., Kamyari, N. & Torabi, M. Improving sleep quality of patients undergoing hemodialysis in Iran through receiving spiritual care program: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 22745 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08637-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08637-4