Abstract

The significance of “L” score in the radius (R), exophytic/endophytic (E), nearness (N), anterior/posterior (A), location (L); RENAL nephrometry scoring system remains unestablished compared to other subscores. This study assessed the influence of the “L” score on surgical and functional outcomes of RAPN, dividing renal tumors into medial and lateral relative to the kidney’s central line, to explore its impact on “L” score utility. A retrospective analysis was conducted on 668 RAPN patients, with 405 having medial and 263 lateral renal tumors. Patients who underwent RAPN were retrospectively analyzed, including 405 with medial renal tumors and 263 with lateral renal tumors. In medial tumors, the “L” score independently predicted non-achievement of trifecta (P = 0.011) and pentafecta (P = 0.032). In lateral tumors, the “L” score did not predict non-achievement of these outcomes. In conclusion, significance of the “L” score on surgical outcomes differs between medial and lateral tumors and it is strongly associated with outcomes in medial tumors, whereas its predictive value in lateral tumors is less marked. The RENAL nephrometry score lacks differentiation between medial and lateral tumors; therefore, surgeons should interpret “L” scores with caution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN) has become the standard of treatment for small-size localized renal cell carcinoma. Notably, it has demonstrated better perioperative results compared to laparoscopic partial nephrectomy1,2. Moreover, RAPN has been increasingly reported for complex and challenging tumors such as those > 7 cm in size3,4complete endophytic renal tumors5,6,7and tumors in the elderly8; accordingly, its use is expanding in guidelines. Scoring methods for surgical difficulty include the radius (R), exophytic/endophytic (E), nearness (N), anterior/posterior (A), location (L); RENAL nephrometry score, preoperative aspects and dimensions used for anatomic classifications (PADUA) score, and centrality index (C index)9,10,11.

Among these scores, the RENAL nephrometry score is the most widely used and is reported to predict trifecta12 and pentafecta1 outcomes of RAPN as well as age, tumor size, hypertension, and preoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)5,13,14,15,16,17. Trifecta is defined as negative surgical margin, no-perioperative complications, and a warm ischemia time of ≤ 25 min. Pentafecta is defined as trifecta plus the absence of an upstage of chronic kidney disease and a minimum of 90% total eGFR preservation. Numerous comprehensive reports on subscores of the RENAL nephrometry score, particularly the “R,” “E,” and “N” scores, have provided evidence of the utility of these scores. A high “R” score has been reported to result in prolonged operative time and warm ischemia time4,18whereas a high “E” score has been associated with longer warm ischemia time, positive surgical margin, and lower trifecta achievement5,6,7. Finally, high “N” scores increased perioperative complications and estimated blood loss, which were predictive of collecting system entries19.

Conversely, no comprehensive report has yet been published on the “L” score. Although a few studies suggest that high “L” scores are associated with prolonged operative time and warm ischemia time20,21they also indicate that these scores may independently predict the achievement of trifecta and pentafecta5,17. However, the full significance of the “L” score remains unclear.

This is the first study to comprehensively investigate the influence of the “L” score on surgical and functional outcomes of RAPN. Based on our clinical experience with RAPN, we hypothesized that the impact of the “L” score would be different for tumors located medial to the central line of the kidney (medial renal tumors) and for tumors located lateral to the central line of the kidney (lateral renal tumors). Therefore, we examined the impact of “L” scores on surgical and functional outcomes, including trifecta and pentafecta for medial and lateral renal tumors, respectively.

Methods

Study design

The study included 700 RAPN cases performed at Yokohama City University Hospital by 2023. The Yokohama City University Certified Institutional Review Board approved the current study (approval number: F220700047). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Yokohama City University Certified Institutional Review Board waived the need of obtaining informed consent. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All methods were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Preoperative patient characteristics included age, sex, body mass index (BMI), tumor size, RENAL nephrometry score, and preoperative blood results (hemoglobin, and creatinine). Surgical outcomes and functional outcomes included surgical approach, console time, warm ischemia time, histopathologic findings, pTNM classification, preoperative and 1-year postoperative eGFR, preoperative and 1-year postoperative chronic kidney disease (CKD) grade, trifecta achievement rate, pentafecta achievement rate, positive or negative margins, and perioperative complications.

In this study, the RENAL nephrometry score is classified according to the definition of Kutikov et al.9. Of the 5 components 4 (R, E, N, L) are scored on a 1, 2 or 3-point scale. 1 point of the “L” score (hereafter referred to as L1) is given when the entire tumor is located above the upper or below the lower polar line. 2 points of the “L” score (L2) is given when the lesion crosses polar line. 3 points of the “L” score (L3) is given when > 50% of mass is across polar line, or mass crosses the axial renal midline, or mass is entirely between the polar lines. Similarly, the “E” and “N” scores are defined according to the definition of Kutikov et al.9with E1, E2, and E3 corresponding to 1, 2, and 3 points for the “E” score, and N1, N2, and N3 corresponding to 1, 2, and 3 points for the “N” score, respectively.

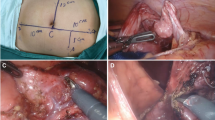

The classification of medial and lateral renal tumors is described below. The medial renal tumor was defined as a tumor where the central line of the tumor is medial to the central line of the kidney on preoperative computed tomography (CT) image, and the lateral renal tumor was defined as a tumor where the central line of the tumor is lateral to the central line of the kidney on preoperative CT image (Fig. 1).

Classification of the medial and lateral renal tumor using coronal section figures of the kidney. (A, B) The medial renal tumor was defined as a tumor where the central line of the tumor is medial to the central line of the kidney on a preoperative CT image. (C) The lateral renal tumor was defined as a tumor where the central line of the tumor is lateral to the central line of the kidney on a preoperative CT image.

Surgical technique

This study involved seven senior consultant urologists with more than 10 years of clinical experience as RAPN surgeons. The Davinci Si and Davinci Xi (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) were used. The operation was performed using four da Vinci arms and one or two assistant ports. The choice of approach was left to the surgeon. If there were no special problems, a transperitoneal approach was chosen if the tumor was located on the anterior side of the kidney, whereas a retroperitoneal approach was selected if the tumor was located on the posterior side of the kidney. The test clamp was conducted after identifying the renal artery, which was clamped using a bulldog clamp. If the tumor was near the renal hilum, the renal vein was also identified and clamped. The Gerota fat was incised around the tumor until the renal capsule was exposed, and the tumor margin was marked using an ARIETTA 70 probe (Hitachi, Inc, Tokyo, Japan). The renal artery and vein were clamped with bulldog clamps, and the tumor was resected. During tumor resection, suction and the vessel sealing device were performed by the assistant to control bleeding. After resection, 3 − 0 barbed sutures were used to suture the vessels and urinary tract at the renal base, and the renal parenchyma was de-clamped with 1 stitch of 0-barbed sutures. If there was arterial bleeding after de-clamping, additional sutures were performed with 3 − 0 barbed sutures. If there was no arterial bleeding, the renal parenchyma was sutured continuously with 0-barbed sutures. Finally, the Gerota fascia was sutured continuously with 2 − 0 absorbable sutures. Finally, the drain was placed in all cases.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables that followed a normal distribution are presented using mean and standard deviation. Nominal variables were compared across the three groups using the chi-square test. For continuous variables following a normal distribution, analysis involved the Turkey T test or the Games-Howell method; those not following a normal distribution were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Multivariate binomial logistic regression with the forced entry method was utilized to identify predictors of trifecta and pentafecta non-achievement in medial and lateral renal tumors, considering sex, age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, BMI, tumor size, “E” score, “N” score, “L” score, surgical approach, and preoperative eGFR as covariates. All statistical tests were two-tailed, performed at a significance level of P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software version 29 (IBM Corporation, New York, USA).

Result

Of the 700 cases, 17 with solitary kidney, 13 with multiple renal tumors, and two of multiple RAPNs performed on a single kidney were excluded. A total of 668 cases were enrolled, with 405 cases of medial renal tumors and 263 cases of lateral renal tumors (Fig. 2).

Overall population (n = 668, Table 1)

Patient characteristics

Tumor size was significantly smaller at L1 compared to L2 and L3 (P < 0.001). The higher the “L” score, the higher the total RENAL nephrometry score (P < 0.001), “E” score (P < 0.001), and “N” score (P < 0.001). Preoperative blood test values (hemoglobin and creatinine) did not show any correlation with the “L” score.

Surgical outcomes

The rates of achieving trifecta (P < 0.001) and pentafecta (P = 0.004) were significantly lower in L2 and L3 compared to L1. Warm ischemia time was significantly shorter in L1 compared to L2 and L3 (P < 0.001).

Medial renal tumors (n = 405, Table 2)

Patient characteristics

Tumor size (P < 0.001) was significantly smaller in L1 compared to L2 and L3. Similar to the overall population, higher “L” scores were associated with higher total RENAL nephrometry scores (P < 0.001), “E” scores (P < 0.001), and “N” scores (P < 0.001). Preoperative blood test values did not show any correlation with the “L” score.

Surgical outcomes

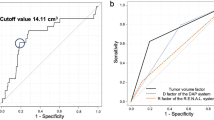

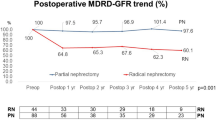

As in the overall population, the rate of achieving trifecta (P < 0.001) and pentafecta (P < 0.001) were significantly lower in L2 and L3 compared to L1 (Fig. 3). The higher the “L” score, the longer the console time (P = 0.004). Warm ischemia time (P < 0.001) was significantly shorter for L1 than for L2 and L3.

Lateral renal tumors (n = 263, Table 3)

Patient characteristics

Tumor size (P < 0.001) was significantly smaller in L1 than in L2 and L3. Similar to the overall population, the higher the “L” score, the higher the total RENAL nephrometry score (P < 0.001) and the “E” score (P = 0.039). Preoperative blood test values did not show any correlation with the “L” score.

Surgical outcomes

Warm ischemia time (P = 0.001) was significantly shorter in L1 than in L2 and L3.

The rate of achieving trifecta tended to be low with high L scores (P = 0.056), and was significantly lower in L2 and L3 than in L1 (P = 0.017). There was no correlation between rates of pentafecta achievement (P = 0.734) and “L” score (Fig. 3).

Predictors of trifecta and pentafecta non-achievement in medial and lateral renal tumors

Multivariate analysis in medial renal tumors (Table 4)

In multivariate analysis, tumor size (odds ratio [OR]: 1.065, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.040–1.091, P < 0.001), “E” score (E1 vs. E2, E3 OR: 2.073, 95%CI: 1.155–3.722, P = 0.015), and “L” score (L1 vs. L2, L3 OR: 2.081, 95%CI: 1.179–3.671, P = 0.011) were identified as predictors of trifecta non-achievement. Tumor size (OR: 1.036, 95%CI: 1.006–1.068, P = 0.018), “L” score (L1 vs. L2, L3 OR: 1.922, 95%CI: 1.058–3.49, P = 0.032) and preoperative eGFR (OR: 1.022, 95%CI: 1.001–1.044, P = 0.041) were identified as predictors of non-achievement of pentafecta.

Multivariate analysis in lateral renal tumors (Table 5)

Tumor size was identified as predictors of trifecta non-achievement (OR: 1.06, 95% CI: 1.021–1.10, P = 0.002) and pentafecta non-achievement (OR:1.044, 95%CI:1.004–1.086, P = 0.029).

Discussion

This study examined the impact of the “L” score on patient characteristics, surgical outcomes, and functional outcomes in RAPN. It is the first to analyze how “L” scores affect patient characteristics and the surgical and functional outcomes in patients with medial and lateral renal tumors, respectively. The study suggests that the “L” score is predictive of surgical outcomes, though its effectiveness varies between medial and lateral renal tumors. Since the classification of medial and lateral renal tumors was not incorporated in the RENAL nephrometry score, caution is advised when interpreting “L” scores, and the quality of scoring may be improved by including medial and lateral tumors in the RENAL nephrometry score and other tumor complexity assessment tools.

In this study, L1 vs. L2 and L3 showed significant differences in predicting trifecta (P = < 0.001) and pentafecta (P = < 0.001) achievement rate (Table 2). On the other hand, L2 vs. L3 showed no significant differences in trifecta (P = 0.405) and pentafecta (P = 0.113) achievement rates (data not shown). These findings suggest that the cut-off point for predicting trifecta in the “L” score is between 1 and 2.

For medial renal tumors, higher “L” scores were associated with lower rates of trifecta and pentafecta achievement, and higher “L” scores were an independent predictor of trifecta and pentafecta non-achievement. On the other hand, in lateral tumors, “L” score was not implicated in achieving trifecta and pentafecta. Previous studies have reported that “L” score is an important predictor of trifecta and pentafecta achievement5,16. However, these studies did not examine the impact of “L” score while considering whether the renal tumors were medial or lateral.

Regarding trifecta achievement rates, univariate analysis, but not multivariate analysis, indicated that the achievement rate was relatively higher with lower “L” scores in lateral renal tumors (P = 0.056) and was significant in medial renal tumors (P < 0.001). This may be due to the significantly shorter warm ischemia time associated with low “L” scores, irrespective of the tumor’s location as medial or lateral. Numakura et al. also reported that high “L” scores were linked to prolonged warm ischemia times21. A higher “L” score suggests that the renal tumor is closer to the renal hilum, potentially prolonging the warm ischemia time. Notably, the proximity of medial renal tumors to the renal hilum, compared to lateral renal tumors, is likely to extend the warm ischemia time due to the necessary processing of critical vasculature and the urinary tract.

Trifecta components other than warm ischemia time, namely positive surgical margin and perioperative complication rates, did not differ by “L” score. The positive surgical margin ranged from 0.6 to 2.2% for medial renal tumors and from 0 to 2.5% for lateral renal tumors, similar and lower than the previously reported 1.1–6.5%22. Perioperative complication rates ranged from 3.1 to 7.3% for medial renal tumors and from 2.7 to 3.6% for lateral renal tumors, with a trend toward higher rates for medial renal tumors, though both were lower than the 15.6% previously reported23.

The correlation between pentafecta non-achievement and the “L” score was observed only in medial renal tumors, not in lateral ones. Generally, a high “L” score is expected to significantly impact renal function negatively due to surgical manipulation near the renal sinus. However, this does not necessarily imply poor long-term renal functional preservation in lateral renal tumors.

In this study, the “E” score was identified as an independent predictor of trifecta non-achievement solely in medial renal tumors, indicating that RENAL nephrometry scores other than the “L” score might differ in their predictive abilities when considering medial versus lateral renal tumors. Ito et al.5 noted complete endophytic renal tumors with a 3-point “E” score as an independent predictor of trifecta achievement, whereas Carbonara et al.6 and Motoyama et al.7 observed a weaker association. The variability in these outcomes, as indicated by previous studies, may partly stem from how trifecta achievement varies between medial and lateral renal tumors.

Finally, as a clinical scoring system, some recent reports have shown that AI-generated nephrometry scores are superior to traditional RENAL nephrometry scores, and time-efficient AI-generated nephrometry scores may become increasingly important in the future24.

This study had several limitations. First, it is a single-center, retrospective study. Additionally, the absence of propensity matching between the medial and lateral renal tumor groups could have resulted in significant differences in patient characteristics. Instead, we conducted a multivariate logistic regression analysis, and the real-world data set appears to be valuable.

Conclusions

This is the first report of a study focusing on the “L” score of the RENAL nephrometry score and its effect on medial and lateral renal tumors. In medial renal tumors, the “L” score was identified as an independent predictor of trifecta and pentafecta non-achievement. However, the role of the “L” score in predicting surgical outcomes in lateral renal tumors was less significant. Therefore, this study suggests that the “L” score is useful for predicting surgical outcomes, although its utility varies between medial and lateral renal tumors. This study may caution surgeons regarding the clinical interpretation of the “L” scores.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed in the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Zargar, H. et al. Trifecta and optimal perioperative outcomes of robotic and laparoscopic partial nephrectomy in surgical treatment of small renal masses: a multi-institutional study. BJU Int. 116, 407–414 (2015).

Khalifeh, A. et al. Comparative outcomes and assessment of trifecta in 500 robotic and laparoscopic partial nephrectomy cases: a single surgeon experience. J. Urol. 189, 1236–1242 (2013).

Bertolo, R. et al. Outcomes of robot-assisted partial nephrectomy for clinical T2 renal tumors: a multicenter analysis (ROSULA collaborative group). Eur. Urol. 74, 226–232 (2018).

Delto, J. C. et al. Robot-assisted partial nephrectomy for large renal masses: a multi-institutional series. BJU Int. 121, 908–915 (2018).

Ito, H. et al. Impacts of complete endophytic renal tumors on surgical, functional, and oncological outcomes of robot-assisted partial nephrectomy. J. Endourol. 38, 347–352 (2024).

Carbonara, U. et al. Outcomes of robot-assisted partial nephrectomy for completely endophytic renal tumors: a multicenter analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 47, 1179–1186 (2021).

Motoyama, D. et al. Comparison of perioperative outcomes among patients with exophytic, mesophytic, and endophytic renal tumors undergoing robot-assisted partial nephrectomy. Int. J. Urol. 29, 1026–1030 (2022).

Anceschi, U. et al. Risk factors for progression of chronic kidney disease after robotic partial nephrictomy in elderly patients: results from a multi-institutional collaborative series. Minerva Urol. Nephrol. 74, 452–460 (2022).

Kutikov, A. & Uzzo, R. G. The R.E.N.A.L. Nephrometry score: a comprehensive standardized system for quantitating renal tumor size, location and depth. J. Urol. 182, 844–853 (2009).

Ficarra, V. et al. Preoperative aspects and dimensions used for an anatomical (PADUA) classification of renal tumours in patients who are candidates for nephron-sparing surgery. Eur. Urol. 56, 786–793 (2009).

Simmons, M. N., Ching, C. B., Samplaski, M. K., Park, C. H. & Gill, I. S. Kidney tumor location measurement using the C index method. J. Urol. 183, 1708–1713 (2010).

Hung, A. J., Cai, J., Simmons, M. N. & Gill, I. S. Trifecta in partial nephrectomy. Trifecta J Urol. 189, 36–42 (2013).

Castellucci, R. et al. Trifecta and pentafecta rates after robotic assisted partial nephrectomy: comparative study of patients with renal masses < 4 and ≥ 4 cm. J. Laparoendosc Adv. Surg. Tech. A. 28, 799–803 (2018).

Choi, C. I. et al. Comparison by pentafecta criteria of transperitoneal and retroperitoneal robotic partial nephrectomy for large renal tumors. J. Endourol. 34, 175–183 (2020).

Kahn, A. E., Shumate, A. M., Ball, C. T. & Thiel, D. D. Preoperative factors that predict trifecta and pentafecta in robotic assisted partial nephrectomy. J. Robot Surg. 14, 185–190 (2020).

Sri, D. et al. Robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN) and standardization of outcome reporting: a prospective, observational study on reaching the trifecta and pentafecta. J. Robot Surg. 15, 571–577 (2021).

Kang, M. et al. Predictive factors for achieving superior pentafecta outcomes following robot-assisted partial nephrectomy in patients with localized renal cell carcinoma. J. Endourol. 31, 1231–1236 (2017).

Kim, D. K. et al. Comparison of trifecta and pentafecta outcomes between T1a and T1b renal masses following robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN) with minimum one year follow up: can RAPN for T1b renal masses be feasible? PLOS One. 11, e0151738 (2016).

Castle, S. M., Gorbatiy, V. & Leveillee, R. J. Robotic partial nephrectomy outcomes at a single institution and experience with R.E.N.A.L. Nephrometry score. J. Robot Surg. 5, 209–214 (2011).

Mayer, W. A. et al. Higher RENAL nephrometry score is predictive of longer warm ischemia time and collecting system entry during laparoscopic and robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy. Urology 79, 1052–1056 (2012).

Numakura, K. et al. Factors influencing warm ischemia time in robot-assisted partial nephrectomy change depending on the surgeon’s experience. World J. Surg. Oncol. 20, 202 (2022).

Wu, Z. et al. Robotic versus open partial nephrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS One. 9, e94878 (2014).

Tanagho, Y. S. et al. Perioperative complications of robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: analysis of 886 patients at 5 united States centers. Urology 81, 573–579 (2013).

Abdallah, N. et al. AI-generated R.E.N.A.L.+ score surpasses human-generated score in predicting renal oncologic outcomes. Urology 180, 160–167 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.N. : Protocol/project development, data collection and management, data analysis, and manuscript writing/editing. H.I. : Protocol/project development, Data analysis. S.H, K.K, R.J, T.T, G.N, D.U, M.K, Y.I, K.M, K.K, H.H, K.M. : Protocol/project developmentAll authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Numata, Y., Ito, H., Honda, S. et al. Impact of the “L” score from the RENAL nephrometry score on RAPN surgical outcomes in medial versus lateral renal tumors. Sci Rep 15, 23106 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08647-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08647-2