Abstract

This study aimed to explore the association between the advanced lung cancer inflammation (ALI) index and the risk of mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis. This retrospective study included 6489 critically ill patients with sepsis from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care-IV (MIMIC-IV) database. The participants were grouped into four groups according to the ALI index quartiles. The outcome was in-hospital mortality and intensive care unit (ICU) mortality. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis and restricted cubic spline regression were used to evaluate the association between the ALI index and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients with sepsis. A total of 6489 patients (59.1% male) were included in the study. The in-hospital and ICU mortality were 25.4% and 19.0%, respectively. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis showed that the ALI index was independently associated with all-cause mortality. After confounders adjusting, ALI index had a significant association with hospital mortality (adjusted hazards ratio, 0.990; 95% confidence interval, 0.985–0.996; P < 0.001) and ICU mortality (adjusted hazards ratio, 0.991; 95% confidence interval, 0.985–0.997; P = 0.004). Restricted cubic splines revealed a non-linear association between ALI and all-cause mortality in sepsis patients. Our study indicates that the ALI index has a significant association with hospital and ICU all-cause mortality in critically ill sepsis patients. However, further confirmation of these findings necessitates larger prospective studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sepsis is a life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection1. It remains a significant contributor to morbidity and mortality in intensive care unit (ICU), with short-term mortality rates reaching up to 50%, depending on the severity of the illness2.

Traditional prognostic scores such as Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) primarily focus on organ dysfunction severity but lack a comprehensive evaluation of nutritional and inflammatory status, which were both pivotal in sepsis progression3,4. As key indicators for assessing nutritional and inflammatory status, multiple studies have confirmed that an elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), reduced serum albumin levels, and low body mass index (BMI) are all significantly associated with poor prognosis in sepsis patients5,6,7. However, single indicator is insufficient to fully reveal the mechanisms of synergistic imbalance between inflammatory responses and nutritional status, as well as the intrinsic relationship between such imbalances and mortality in sepsis.

The advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) is a comprehensive index developed in recent years to assess the nutritional and inflammatory status of patients, encompassing parameters such as albumin, BMI, and NLR8,9. All of these parameters are derived from routine laboratory tests and anthropometric measurements, making them highly compatible with standardized electronic health records (EHRs) fields such as body weight, complete blood count, and biochemical indicators10. This composition makes ALI well suited to structured datasets and suggests its potential for automated, real-time monitoring to enable early detection of nutrition and inflammation imbalances.

This tripartite metric uniquely bridges nutritional reserves (albumin/BMI) and systemic inflammation (NLR), makes ALI index an effective prognostic tool for cancer patients11,12,13. In addition, studies have found ALI index to be associated with prognosis in a variety of inflammatory diseases, such as coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes14,15,16,17. Notably, lower ALI scores at ICU admission in critically ill heart failure patients independently predict higher in-hospital and 90-day mortality risk, further validating the index’s potential utility in critical care management14.

However, the relationship between ALI index and prognosis of sepsis is currently not well understood. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the role of the ALI index in predicting all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis by analyzing the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV).

Materials and methods

Study population

We conducted a retrospective observational study using data from the publicly available MIMIC-IV3.1 database, covering January 1, 2008, to December 31, 201918. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, MA) and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (Boston, MA). The author Lei Zhang completed the required Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) program and was granted access to the database (Record ID: 64101469). A waiver of informed consent was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (Boston, MA), given the retrospective nature of the study and the use of fully de-identified data. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

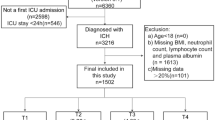

We included adult patients meeting Sepsis-3 criteria, which are defined as suspected or confirmed infection plus a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score ≥ 2 within 24 h of ICU admission19. The exclusion criteria were: (1) patients aged less than 18 years at the time of first admission; (2) length of stay in ICU was less than 48 h; (3) patients with multiple admissions to the ICU for sepsis, for whom only from the first admission data were extracted; (4) missing BMI, Albumin, neutrophil, and lymphocyte counts within 24 h of admission. The flowchart of this study is presented in Fig. 1.

Variable extraction

The software PostgreSQL (version 16.1.0) and Navicat Premium (version 17.1.9) were used to extract information with a running Structured Query Language (SQL). We extracted data from the MIMIC-IV3.1 database for the first 24 h of ICU admission, including patient demographics (age, gender, BMI, race), vital signs (temperature, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), heart rate, respiration rate, and pulse oximeter oxygen saturation (SpO2)), and admission severity metrics (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA), Acute Physiology Score III (APS III), Simplified Acute Physiological Score II (SAPS II), Oxford Acute Severity of Illness Score (OASIS) and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)). Other relevant data, including laboratory test results, clinical outcomes, and comorbidities were obtained. All laboratory parameters extracted from the MIMIC-IV3.1 database were measured at the first time after ICU admission. Follow-up began on the admission date and ended on the date of death. ALI index upon admission was calculated using the following formula: ALI index = BMI × Alb / NLR, where BMI is weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared, Alb is serum albumin in grams per deciliter, and NLR is the ratio of absolute neutrophil count to absolute lymphocyte count.

To minimize bias, variables were excluded if they had more than 20% missing values. Variables with missing data less than 20% were processed by multiple imputation using a random forest algorithm (trained by other non-missing variables) by the “mice” package of R software (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Clinical outcomes

The primary endpoint was all-cause in-hospital mortality, and the second endpoint was ICU mortality. Patient mortality information for discharged patients was accessed from the US Social Security Death Index.

Statistical analysis

The ALI index was divided into four groups according to quartiles. Categorical variables were evaluated using Fisher’s exact or chi-square tests and were presented as counts (percentages). For continuous variables, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Student’s t-test, or one-way analysis of variance were employed. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was employed to assess the incidence of endpoints across groups stratified by different ALI index levels, with differences evaluated via log-rank tests. Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate the hazards ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association between the ALI index and endpoints, and also adjusted for some models. And clinically relevant and prognosis-associated variables were also enrolled in the multivariate model: model 1: unadjusted; model 2: adjusted for age, gender, race; model 3 adjusted for age, gender, race, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, myocardial infarction, renal failure, sofa, Platelets, white blood cell (WBC) count, alkaline phosphatase (Alp), prothrombin time (Ptt), aspartate aminotransferase (Ast), international normalized ratio (Inr), prothrombin time (Pt), Hemoglobin, Sodium, alanine aminotransferase (Alt).

Further, we also analyzed the nonlinear association between baseline ALI indexand hospital all-cause mortality and ICU mortality using a restricted cubic spline analysis. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to determine the cutoff value of the ALI index. The ALI index was entered into the models as continuous variable or ordinal variables (the first quartile of the ALI index was set as a reference group). The P values for trends were calculated using the quartile levels. Subgroup analyses were performed to explore potential differences across various subgroups based on age (< 65 and ≥ 65 years), gender, BMI (< 30 and ≥ 30 kg/m2), diabetes, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, myocardial infarction and renal failure, to evaluate the consistency of the prognostic value of the ALI index for primary outcomes. The interactions between ALI index and variables used for stratification were tested using likelihood ratio tests. Data processing and analysis were carried out via R version 4.4.2, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05 for two-tailed tests.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 6489 patients were included in the final data analysis. The median age of the included patients was 65.14 (IQR: 53.92–76.21) years, and 3837 (59.1%) were men. In-hospital, ICU, 30-day, and 90-day mortality rates were 25.4%, 19.0%, 28.0% and 37.0%, respectively. Patients were stratified into four groups based on the quartiles of ALI index as follows: Q1 (ALI < 4.6; n = 1623), Q2 (4.6–8.8; n = 1622), Q3 (8.8–16.3; n = 1622) and Q4 (ALI ≥ 16.3; n = 1622). The baseline characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. Compared with higher quartiles, Q1 patients had lower BMI, temperature, SBP, DBP, SpO₂, hematocrit, lymphocyte, albumin, bicarbonate, chloride, sodium, basophil, eosinophil, calcium, and hemoglobin. They also had higher age, SOFA, APS III, SAPS II, OASIS, heart rate, respiration rate, WBC, neutrophil, anion gap, creatinine, total bilirubin, ALP, INR, PT, Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN), and in-hospital, ICU, 30-day, and 90-day mortality, and higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation and renal failure. In the non-survivor group (Table 2), patients were older, had higher severity scores, greater prevalence of atrial fibrillation, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and renal failure, and higher WBC, monocyte, neutrophil, anion gap, creatinine, potassium, total bilirubin, ALT, ALP, PTT, AST, INR, PT, calcium, and BUN. The median ALI index was significantly lower in non-survivors than survivors (7.33 vs. 9.39; P < 0.001).

Primary outcomes

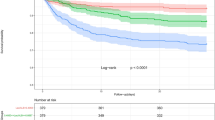

The Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the primary outcomes, stratified by ALI index quartiles, are presented in Fig. 2. Significant differences were observerd at 30-day and 90-day (log-rank P all < 0.001). We evaluated the the diagnostic efficacy of the ALI index using the ROC analysis. However, the area under the curve (AUC) of ALI index was not good enough (in hospital death AUC:0.571, P < 0.001; ICU death AUC: 0.560, P < 0.001 ). The cutoff value of ALI index was 7.78 and 7.18 for hospital death and ICU death, respectively.

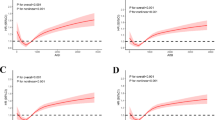

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis showed that the ALI index was independently associated with lower in-hospital mortality (HR, 0.990; 95% CI, 0.985–0.996; P < 0.001), and ICU mortality (HR, 0.991; 95% CI, 0.985–0.997; P = 0.004). These results were further confirmed in the fully adjusted Model 3, specifically, the HR for in-hospital mortality in the highest ALI index quartile was 0.711 (95% CI, 0.615–0.822; P < 0.001), and for ICU mortality, it was 0.730 (95% CI, 0.615–0.867; P < 0.001), both compared with the lowest quartile. Compared with the Q1 group, the Q2, Q3 and Q4 groups exhibited significantly lower risks of in-hospital and ICU mortality, with all trend p-values below 0.05 (Table 3; Fig. 3a and b). Furthermore, the results of the restricted cubic spline analysis indicated a non-linear relationship between the ALI index and both hospital mortality and ICU mortality in sepsis patients (P for non-linearity = 0.012 and P for non-linearity = 0.025, respectively), and low levels of ALI index were associated with an increased risk of hospital mortality and ICU mortality in this population (Fig. 3c and d).

The relationship for the levels of ALI index with in-hospital mortality and ICU mortality. (a, b) Hazards ratios (95% CIs) for in-hospital and in-ICU mortality according to ALI index quartiles after adjusting for sex, age, race, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, myocardial infarction, renal failure, Sofa, Platelets, WBC, Alp, Ptt, Ast, Inr, Pt, Hemoglobin, Sodium, Alt. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. The first quartile is the reference. (c) Restricted cubic spline for hospital mortality. (d) Restricted cubic spline for ICU mortality. HR, hazards ratio; CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit; ALI, advanced lung cancer inflammation.

Subgroup analysis

To further evaluate the association between ALI and mortality, we performed stratified analyses for in-hospital and ICU deaths by age, gender, BMI, diabetes, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, myocardial infarction, and renal failure (Figs. 4 and 5). Subgroup analysis showed that the association between the ALI index and risk of in-hospital mortality was consistent across subgroups stratified by age, gender, BMI, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, myocardial infarction (P for interaction > 0.05). In contrast, two significant interactions were observed in subgroup defined by hypertension and renal failure (P for interaction = 0.001 and 0.003, respectively; Fig. 4). For ICU mortality stratified analyses, no significant interactions were identified between the ALI index and age, gender, BMI, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, heart failure (P for interaction > 0.05; Fig. 5). However, hypertension, renal failure and myocardial infarction showed significant interaction (P for interaction < 0.05; Fig. 5). The results of the stratifed analysis consistently demonstrated a consistent association of ALI index values across most sub-populations.

Discussion

In the present study, we used the open-source MIMIC-IV3.1 database to evaluate the ability of the ALI index to predict short-term outcomes among critically ill patients with sepsis. The results of this study indicated that a lower ALI index was significantly associations with all-cause ICU and hospital mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis. Even after adjusting for confounding risk factors, the ALI index was still strongly associated with all-cause ICU and hospital mortality. Building on its established use in critically ill heart failure patients, our findings extend the ALI index’s applicability to sepsis critical illness, demonstrating consistent prognostic value across diverse acute care populations.Sepsis is a life-threatening medical condition that occurs when the host mounts an uncontrolled or abnormal immune response to overwhelming infection20. In sepsis, there is a series of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory reactions that lead to complications such as fever, cardiovascular shock, and systemic organ failure in patients21. The involvement of inflammatory mediators, neurotransmitters, and gene regulators drives the development of local inflammatory responses22. Multiple studies have shown that interleukin-6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), and NLR are closely associated with prognosis in sepsis patients23,24. On one hand, low albumin levels are associated with increased risk of sepsis and mortality25. On the other hand, BMI serves as an independent predictor of in-hospital death in sepsis patients, with those having higher BMI exhibiting lower mortality26. These findings suggest that both inflammatory and nutritional status should be taken into account when comprehensively assessing the prognosis of sepsis patients.

The ALI index is calculated by combining serum albumin, BMI and the inflammatory parameter NLR, and has been proven to predict prognosis in various cancers27,28,29,30. Unlike previous indices that include only NLR and albumin, ALI also incorporates BMI to assess nutritional status. A recent study showed that the ALI index was associated with long-term all-cause mortality in gastric cancer patients, serving as a comprehensive indicator of nutrition status and inflammation31. Another study demonstrated that the ALI index was superior to the prognostic nutritional index, NLR, and systemic immunoinflammatory index in predicting and differentiating sarcopenia32.

From an ICU management perspective, the ALI index provides a physiologically informed measure of the nutrition–inflammation interplay. Unlike manually recorded organ dysfunction scores such as SOFA or APACHE II, the ALI index leverages automated data extraction from EHRs to dynamically calculate risk scores, positioning it as a promising tool for real-time risk stratification in sepsis patients33. Clinically validated ALI cut-points enable classification of sepsis patients into distinct risk tiers, each aligned with tailored intervention protocols34. For example, patients with low ALI scores should promptly receive intensified therapy, including NLR-guided immune modulation, early correction of hypoalbuminemia, and BMI-adjusted high-calorie, high-protein enteral nutrition, to address severe nutrition–inflammation imbalance35,36,37. When integrated into ICU workflows, the ALI index functions not only as a prognostic marker but also as a decision-support tool bridging pathophysiological mechanisms with precision-guided early interventions.

Our results suggested that a higher ALI index was associated with a lower risk of hospital and ICU death. Several elements might underlie this complex relationship. Firstly, the prognosis of sepsis is closely tied to the severity of inflammatory responses. Previous studies had indicated that the NLR represented the inflammatory immune response, and a high neutrophil count was a sign of non-specific inflammation, while a low lymphocyte count suggested a relative deficiency in immune regulation38. Furthermore, a correlation between elevated NLR and poorer prognoses in sepsis patients was found in prior studies5. The findings in Table 1 revealed that spanning from group Q1 to Q4, there was a significant decrease in neutrophils and a significant increase in lymphocytes, with a corresponding decrease in NLR, paralleled by a substantial decline in the risk of all-cause mortality. Therefore, we proposed a consistent trend: a decrease in NLR correlated with a concurrent reduction in mortality risk in sepsis patients. Secondly, serum albumin was a frequently utilized marker for assessing nutritional status. Prior studies indicated a negative correlation between albumin levels and the incidence of sepsis39. Owing to its anti-inflammatory effects, albumin served an essential role in sepsis therapy. Sepsis patients with higher albumin levels had a better prognosis compared to those with lower levels. This evidence suggested that albumin levels were closely related to the occurrence of sepsis, the progression of complications, and prognosis. In this study, we noticed that from group Q1 to Q4, albumin levels gradually increased, and all-cause mortality significantly decreased. Therefore, we believed that the elevated albumin levels mainly contributed to consistent decrease in the risk of all-cause mortality for sepsis patients. Finally, we examined the impact of BMI on the mortality of sepsis patients. Obesity was often a high-risk factor for a variety of diseases. However, the relationship between BMI and the prognosis of sepsis patients was controversial40. Previous studies had shown that sepsis patients with higher BMI had a lower mortality rate, a paradox that might be explained by the obesity paradox41. In other words, obesity was associated with a lower mortality rate in sepsis. The underlying mechanism might be that patients with higher BMI had stronger anti-inflammatory capabilities42. This study indicated that as BMI levels increased from Q1 to Q4, the risk of all-cause mortality among patients with sepsis significantly decreased.

Our study further analyzed the risk stratification of various subgroups. The results suggested that the predictive value of the ALI index for hospital mortality and ICU mortality was consistent among sepsis patients, regardless of age, gender, obesity, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure. However, we did not observe a significant association between ALI and in-hospital mortality among patients with baseline diabetes or myocardial infarction possibly because these comorbidities independently confer a poorer prognosis43,44. Additionally, the current study revealed that the predictive value of the ALI index significantly differs between sepsis patients with and without atrial fibrillation and between those with and without renal failure. This was because sepsis patients with renal failure had a higher mortality rate, and hypertension could reduce the mortality rate45,46. Finally, we confirmed a significant linear relationship between the ALI index and in-hospital mortality, supporting that the ALI index could be a reliable tool for detecting high mortality risk in sepsis patients.

Notably, although a similar study was recently published after our submission47, our research presents several important distinctions. We employed the updated MIMIC-IV3.1 database with a larger sample size, incorporated survival analysis for 90-day mortality, conducted comprehensive in-hospital all-cause mortality analysis, and performed more granular subgroup stratifications. Together, these features enhance the robustness and clinical applicability of our findings regarding the prognostic value of the ALI index in critically ill sepsis patients.

This study has several strengths. Firstly, our analysis based on a large public database with nationally representativeness, verified that the ALI index was an important independent risk factor in critically ill patients with sepsis in a US cohort. Secondly, we considered a multitude of confounding factors and utilized multivariable-adjusted Cox analysis, stratified analysis, and interaction analysis. Lastly, the ALI index is an easily calculable and derivable comprehensive index, offering high convenience and practicality for clinical use.

This study also has some limitations. First, as this was an observational research, it cannot definitively establish a causal link between the ALI index and the mortality associated with sepsis patients. Second, we collected data from the first-time measurements, and did not dynamically monitor the data during the follow-up period. To address these limitations, we plan to leverage hospital EHR data to expand the sample size, clarify the causality, employ additional statistical methods to minimize bias, and perform external validation in independent cohorts or diverse populations.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results extended the utility of the ALI index to critically ill patients with sepsis and demonstrated that the ALI index could be used as a potential index for risk stratification of in-hospital and ICU mortality among these patients. Therefore, enhancing risk assessment and directing subsequent interventions. However, additional prospective studies are required to validate these findings.

Data availability

The data utilized in this study were sourced from the MIMIC-IV database. For more information about the database, please visit: https://mimic.physionet.org/. The datasets extracted and analyzed during this study can be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Fleischmann, C. et al. Assessment of global incidence and mortality of Hospital-treated sepsis. Current estimates and limitations. Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 193 (3), 259–272 (2016).

Huang, S. et al. Effectiveness of sodium bicarbonate infusion on mortality for elderly septic patients with acute metabolic acidosis. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 974271 (2022).

Vincent, J. L. et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related organ failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on Sepsis-Related problems of the European society of intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med. 22 (7), 707–710 (1996).

Akavipat, P., Thinkhamrop, J., Thinkhamrop, B. & Sriraj, W. Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (apache) ii score - the clinical predictor in neurosurgical intensive care unit: Acta Clin. Croatica 58(1):50–56. (2019).

Huang, Z., Fu, Z., Huang, W. & Huang, K. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in sepsis: A meta-analysis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 38 (3), 641–647 (2020).

Frenkel, A., Novack, V., Bichovsky, Y., Klein, M. & Dreiher, J. Serum albumin levels as a predictor of mortality in patients with sepsis: A multicenter study. Isr. Med. Association Journal: IMAJ. 24 (7), 454–459 (2022).

Li, S. et al. Increased body mass index linked to greater short- and long-term survival in sepsis patients: A retrospective analysis of a large clinical database. Int. J. Infect. Diseases: IJID : Official Publication Int. Soc. Infect. Dis. 87, 109–116 (2019).

Yao, J., Chen, X., Meng, F., Cao, H. & Shu, X. Combined influence of nutritional and inflammatory status and depressive symptoms on mortality among US cancer survivors: findings from the NHANES. Brain. Behav. Immun. 115, 109–117 (2024).

Yin, C. et al. Clinical significance of advanced lung cancer inflammation index, a nutritional and inflammation index, in gastric cancer patients after surgical resection: A propensity score matching analysis. Clin. Nutr. 40 (3), 1130–1136 (2021).

Miao, S. et al. The construction and application of a clinical decision support system for cardiovascular diseases: multimodal Data-Driven development and validation study. JMIR Med. Inf. 13, e63186 (2025).

Topkan, E. et al. Prognostic usefulness of advanced lung Cancer inflammation index in Locally-Advanced pancreatic carcinoma patients treated with radical chemoradiotherapy. Cancer Manage. Res. 11, 8807–8815 (2019).

Shibutani, M. et al. The prognostic significance of the advanced lung cancer inflammation index in patients with unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer: a retrospective study. BMC cancer. 19 (1), 241 (2019).

Mountzios, G. et al. Association of the advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) with immune checkpoint inhibitor efficacy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. ESMO Open. 6 (5), 100254 (2021).

Chen, Y., Guan, M., Wang, R. & Wang, X. Relationship between advanced lung cancer inflammation index and long-term all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: NHANES, 1999–2018. Front. Endocrinol. 14, 1298345 (2023).

Fan, W. et al. Nomograms based on the advanced lung Cancer inflammation index for the prediction of coronary artery disease and calcification. Clin. Appl. Thrombosis/hemostasis: Official J. Int. Acad. Clin. Appl. Thrombosis/Hemostasis. 27, 10760296211060455 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. The advanced lung cancer inflammation index predicts long-term outcomes in patients with hypertension: National health and nutrition examination study, 1999–2014. Front. Nutr. 9, 989914 (2022).

Yuan, X., Huang, B., Wang, R., Tie, H. & Luo, S. The prognostic value of advanced lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) in elderly patients with heart failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 934551 (2022).

Johnson, A. E. W. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data. 10 (1), 1 (2023).

Singer, M. et al. The third international consensus definitions for Sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). Jama 315 (8), 801–810 (2016).

Wang, W., Ma, L., Liu, B. & Ouyang, L. The role of trained immunity in sepsis. Front. Immunol. 15, 1449986 (2024).

Doganyigit, Z., Eroglu, E. & Akyuz, E. Inflammatory mediators of cytokines and chemokines in sepsis: from bench to bedside. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 41, 9603271221078871 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Microglia: A potential therapeutic target for Sepsis-Associated encephalopathy and Sepsis-Associated chronic pain. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 600421 (2020).

Barichello, T., Generoso, J. S., Singer, M. & Dal-Pizzol, F. Biomarkers for sepsis: more than just fever and leukocytosis-a narrative review. Crit. Care. (London, England). 26 (1), 14 (2022).

Saxena, J. et al. Biomarkers in sepsis. Clin. Chim. Acta. 562, 119891 (2024).

Geng, L. et al. Different concentrations of albumin versus crystalloid in patients with Sepsis and septic shock: A Meta-Analysis of randomized clinical trials. J. Intensive Care Med. 38 (8), 679–689 (2023).

Ye, L., Feng, M., Lin, Q., Li, F. & Lyu, J. Analysis of pathogenic factors on the death rate of sepsis patients. PloS One. 18 (12), e0287254 (2023).

Jafri, S. H., Shi, R. & Mills, G. Advance lung cancer inflammation index (ALI) at diagnosis is a prognostic marker in patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a retrospective review. BMC cancer. 13, 158 (2013).

Feng, J. F., Huang, Y. & Chen, Q. X. A new inflammation index is useful for patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. OncoTargets Therapy. 7, 1811–1815 (2014).

Park, Y. H., Yi, H. G., Lee, M. H., Kim, C. S. & Lim, J. H. Prognostic value of the pretreatment advanced lung Cancer inflammation index (ALI) in diffuse large B cell lymphoma patients treated with R-CHOP chemotherapy. Acta Haematol. 137 (2), 76–85 (2017).

Tsai, Y. T. et al. Advanced lung Cancer inflammation index predicts survival outcomes of patients with oral cavity Cancer following curative surgery. Front. Oncol. 11, 609314 (2021).

Guner, A. et al. Parameters for predicting surgical outcomes for gastric Cancer patients: simple is better than complex. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 25 (11), 3239–3247 (2018).

Ren, Z., Wu, J., Wu, S., Zhang, M. & Shen, S. The advanced lung cancer inflammation index is associated with mortality in peritoneal dialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 25 (1), 208 (2024).

Shi, S. et al. Developing a rapid screening tool for high-risk ICU patients of sepsis: integrating electronic medical records with machine learning methods for mortality prediction in hospitalized patients-model establishment, internal and external validation, and visualization. J. Translational Med. 23 (1), 97 (2025).

Carlton, E. F. Toward tailored care for Sepsis survivors. Annals Am. Thorac. Soc. 19 (8), 1271–1272 (2022).

Cao, M., Wang, G. & Xie, J. Immune dysregulation in sepsis: experiences, lessons and perspectives. Cell. Death Discovery. 9 (1), 465 (2023).

Wiedermann, C. J. Moderator effect of hypoalbuminemia in volume resuscitation and plasma expansion with intravenous albumin solution. International J. Mol. Sciences. 23(22),14175 (2022).

Safabakhsh, M. et al. Efficacy of dietary supplements on mortality and clinical outcomes in adults with sepsis and septic shock: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 43 (6), 1299–1307 (2024).

Azab, B. et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of worsening renal function in diabetic patients (3-year follow-up study). Ren. Fail. 34 (5), 571–576 (2012).

Caironi, P. et al. Albumin replacement in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 370 (15), 1412–1421 (2014).

Wang, S. et al. The role of increased body mass index in outcomes of sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Anesthesiol. 17 (1), 118 (2017).

Lebovitz, S. et al. The relationship between body mass index and In-Hospital mortality in bacteremic Sepsis. Journal Clin. Medicine. 12(11), 3848 (2023).

Antonopoulos, A. S. & Tousoulis, D. The molecular mechanisms of obesity paradox. Cardiovascular. Res. 113 (9), 1074–1086 (2017).

Frydrych, L. M., Bian, G., O’Lone, D. E., Ward, P. A. & Delano, M. J. Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus drive immune dysfunction, infection development, and sepsis mortality. J. Leukoc. Biol. 104 (3), 525–534 (2018).

Desnos, C. et al. Prognostic performance of GRACE and TIMI risk scores in critically ill patients with sepsis and a concomitant myocardial infarction. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 115 (6–7), 359–368 (2022).

Kim, H., Hur, M., Struck, J., Bergmann, A. & Di Somma, S. Proenkephalin predicts organ failure, renal replacement therapy, and mortality in patients with Sepsis. Annals Lab. Med. 40 (6), 466–473 (2020).

Nunes, J. P. Arterial hypertension and sepsis. Revista Portuguesa de cardiologia: Orgao oficial Da sociedade Portuguesa de cardiologia = portuguese. J. Cardiol. : Official J. Portuguese Soc. Cardiol. 22 (11), 1375–1379 (2003).

Li, J. et al. Advanced lung cancer inflammation index and short-term mortality in sepsis: a retrospective analysis. Front. Nutr. 12, 1563311 (2025).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lei Zhang designed the study. Lei Zhang extracted, collected and analyzed data. Minye Li, Jianfei Liu prepared tables and figures. Zhanwei Zhao, Lijun Zhou reviewed the results, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors have made an intellectual contribution to the manuscript and approved the submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Li, M., Liu, J. et al. Association between advanced lung cancer inflammation index and all-cause mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis: analysis of the MIMIC-IV database. Sci Rep 15, 21130 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08713-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08713-9