Abstract

The initiation criterion is utilized to predict the critical detonation condition of explosives and plays a dominant role in the fields of survivability, vulnerability, and safety. In order to predict the threshold criterion of explosives initiated by fragment impact in three-dimensional scenarios, the detonation threshold velocities of Comp B (61% Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine, 39% 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene) explosive charges with different radii under the fragment impact at different polar angles and azimuth angles were obtained by numerical calculations, and further, a three-dimensional initiation criterion was established. The results show that when the impact polar angle of the fragment is fixed, the critical velocity under the same azimuth angle scenario increases as the radius of the charge decreases. When the impact azimuth angle of the fragment is fixed, the critical velocity under the same polar angle scenario is almost unaffected by the charge radius. The maximum error between the three-dimensional initiation criterion and the simulation is 3.09%, indicating the high accuracy of the established initiation criterion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Explosive charges can be shock initiated by warhead fragment impact in a complex battlefield environment, resulting in safety problems. The criterion of shock initiation is usually used to predict the critical detonation condition of the explosive charge under the impact of a projectile. Intensive research on the shock initiation of explosives by fragment impact is of great significance for explosive applications in the fields of survivability, vulnerability, and safety1.

The ignition and initiation phenomenon of energetic material by projectile impact has been widely discussed with extensive experimental and numerical research2,3,4,5. The shock initiation process of explosive charge by projectile impact has been deeply understood by analyzing the influence of projectile variables (including but not limited to multiple fragments6,7, projectile density8, projectile diameter9), as well as the charge variables (such as specimen size10, charge age11, and charge temperature12). Based on the analysis of the effect of certain variables on shock initiation, it is of great importance to establish a mathematical model or initiation criterion to predict the shock initiation criterion. In the research by Leus13, the effect of the tangential velocity components of a fragment on critical velocity was investigated, and a modified Jacobs-Roslund initiation model was established. Moreover, the influence of the impact angle and the charge radius was analyzed in Ref.14, and based on the Picatinny engineering criterion, a modified critical velocity model considering the impact angle within a two-dimensional plane was proposed. Clearly, past works have concentrated on the influence of the impact angle within a two-dimensional plane, while the explosive charge could be impacted by fragments at any angle in practice. Hence, a three-dimensional initiation criterion was needed to predict the critical velocity in the complex scenarios.

In this study, the physical model of a fragment impacting an explosive charge at any angle was established, and the influence of explosive radius, impact polar angle, and impact azimuth angle on detonation threshold velocity was investigated. Further, the correlation between variables was analyzed, and a three-dimensional initiation criterion that can predict the critical velocity with different radii under any angle impact was established.

Physics model and initiation criterion

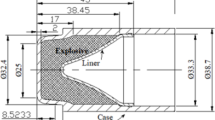

The three-dimensional model of a spherical fragment impacting a cylindrical explosive charge is sketched in Fig. 1, where charge radius r, fragment diameter d, and fragment impacting velocity v are the main variables. A spherical coordinate system and a Cartesian coordinate system were established with the center of the spherical fragment as the origin point. The velocity vector direction of fragments is controlled by the polar angle θ and azimuth angle φ in the spherical coordinate system, and the velocity components in each direction of the Cartesian coordinate system are:

where: vx, vy, and vz are the velocity components of the fragment velocity vector v in the x, y, and z axis directions, respectively.

One of the most commonly used threshold initiations, the u2d criterion (u is cratering velocity)15, considering fragment density and charge density was established based on a large number of impact initiation tests of explosive charge. The critical velocity criterion for the initiation of explosives by fragment was given as follows.

where v0 is the critical velocity required to produce a detonation, ρt is the charge density, ρp is the fragment density, Icr is the critical initiation criterion of explosive charge, and d is the fragment diameter. The u2d criterion can accurately predict the initiation criterion of plane charge when the fragment impacts vertically, while it is not applicable when the impact angle is not vertical or the shape of the charge is cylindrical. Therefore, a three-dimensional initiation criterion considering the polar angle, azimuth angle, and charge radius was proposed in this investigation based on the u2d criterion, which can predict the initiation criterion of explosive charge with different radii under the fragment impact at any angle.

The criterion correction factor f(δ) is defined as the increment of the detonation threshold velocity of the explosive charge.

where v(θ,φ,r) is the detonation threshold velocity when the fragment impacts charges with different radii at different polar angles and azimuths, v0 is the critical velocity required to produce a detonation when the fragment vertically impacts the plane charge. The value of v(θ,φ,r) in this investigation is determined by numerical simulation, and the value of v0 is determined by the u2d criterion. The three-dimensional velocity criterion for explosive charge considering the impact polar angle, impact azimuth angle, and radius is defined as:

The purpose of this investigation is to determine the specific expression form of f(δ), so as to establish a complete critical velocity criterion for fragment impact initiating explosive charge.

Numerical simulation calculations

Numerical simulation model

In the case of interaction between fragments and explosive charges, there were both deformation processes of fragments and explosive charges, as well as the shock initiation process of explosives. The Lagrange algorithm was used for fragments and explosive charges for precision and efficiency. A 0.8 mm mesh size was applied for fragments and explosives, as preliminary simulations showed that the calculation results were convergent when the mesh size was less than 0.8 mm.

Considering that the only concern is whether the explosive was initiated under the fragment impact, the subsequent expansion process of detonation products was not important. Within a few microseconds, after the fragment impacts the explosive charge, the reaction level of explosives can usually be judged by observing the stress or fraction diagram of the simulation model. Hence, a simplified simulation model was established for more efficient calculations. As shown in Fig. 2, a part of the cylindrical explosive with a thickness of 80 mm was extracted to refine the mesh, and the other part was abandoned. Preliminary calculations showed that the reaction state of the explosive could be determined before the stress wave reached the boundary of the simplified explosive model, indicating that the size of the extracted simplified model was large enough and could meet the application requirements in this investigation. In addition, a series of gauge points (shown in Fig. 1) were set inside the explosive along the impact velocity vector to record the pressure histories. The distance between adjacent gauge points was 5 mm.

Material model

The Jones-Wilkins-Lee (JWL) equations of state in temperature-dependent form were used for both the unreacted explosive and the reaction products16,17:

where p is the pressure; V is volume of the explosive at pressure p divided by the initial volume of the unreacted explosive, CV is the average heat capacity, T is the temperature, and A, B, R1, R2, and ω are constants.

The Ignition and Growth (I&G) reactive flow model was used to describe the shock initiation and detonation behaviors of the impacted explosive. The reaction rate equation used the following three-term equation18:

where λ is the fraction of explosive that has reacted, t is time, ρ is the current density, ρ0 is the initial density of explosive, p is pressure, and I, a, b, G1, x, c, d, y, G2, e, g, and z are constants.

Comp B (61% Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine, 39% 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene) is one of the most commonly used military explosives, and extensive numerical and experimental research has been done on shock initiation by fragments, which is also used as a typical explosive in this investigation. The values for I&G model parameters were taken from the work performed by Merphy19 and shown in Table 1 below.

Tungsten alloy was used for the fragment. Gruneisen EOS20 and Johnson–Cook strength equation21 were applied to the tungsten alloy to describe its state under high pressure and deformation characteristics, respectively. The equation parameters were taken from the AUTODYN material library22.

A comparison to experiments was needed to verify the effectiveness of the numerical simulation model established. James and Hewitt23 performed experiments with tungsten sphere projectiles to determine the impact sensitivity of Comp B, where the explosive dimensions were 101 mm in diameter by 70 mm long, and the diameter of tungsten sphere projectiles was 12.75 mm. The projectile velocity direction was perpendicular to the plane charge, and a numerical model (Fig. 3) was established with the same setup as in the experiments. The critical velocity in the experiment was 1750 m/s, while that in the simulation was 1695 m/s. The simulation results showed sufficient consistency with the experiment results, demonstrating that the numerical model was validated.

To further verify the applicability of the numerical model, another comparison to impact experiments24 was carried out, along with the calculated u2d curve. In the experiments, tungsten spherical fragments with different diameters perpendicularly impacted bare Comp B explosives. The comparison between experiments, simulations, and u2d criterion is shown in Fig. 4. It can be seen from Fig. 4 that the critical velocities calculated by simulation were within the range of detonation and non-detonation velocity obtained by tests and consistent with the u2d critical velocity curve, indicating the high precision of the numerical model.

Simulation results

A total of 125 impact scenarios of numerical simulation calculations, namely a tungsten sphere with a mass of 4 g impacted the explosive charge with radii of 80 mm, 120 mm, 160 mm, 200 mm, and ∞ at polar angles θ = 90°, 75°,60°,45°, 30°, and azimuth angles φ = 90°, 75°, 60°, 45°, 30°, respectively, were performed with AUTODYN 3D Hydrocode to analyze the influence of various variables on the detonation threshold velocity. A starting velocity was estimated with the u2d criterion when the polar angle and azimuth angle were both 90° , and then AUTODYN was run to determine if a detonation was predicted. From this starting point, the impact velocity was adjusted up or down until the critical velocity was bounded within ± 5 m/s. The critical velocities were also determined with a ± 5 m/s precision interval for other impact angles. The critical velocities of Comp B explosive charges under different impact scenarios were obtained from the numerical calculation results. The velocity values of v(θ,φ,r) are statistically listed in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6.

By comparing the velocity results of the first row in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, it can be found that when the polar angle θ is 90°, the critical velocities of the explosive charges under the same azimuth scenario increase as cylindrical radii decrease. For example, the critical velocities of the plane, 200 mm, 160 mm, 120 mm, and 80 mm charges increase gradually as radii decrease when θ is 90° and φ is 30°, indicating that the azimuth angle φ is correlated to the radius r. Qualitative analysis showed that when the polar angle was fixed and the azimuth angle changed, the shape of the velocity vector was conical. The intersection line formed by the conical surface of the velocity vector and the cylindrical charge would change as the radius of the charge, indicating that the initial shock wave was affected differently by the rarefaction wave from the boundary. As a result, the smaller the radius, the earlier the initial shock wave was affected by the rarefaction wave from the boundary, and the higher the threshold velocity to detonate the charge.

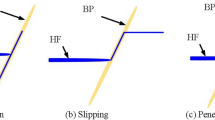

Numerical calculations of typical impact scenarios were compared for further analysis. Figure 5a, b present the pressure field in a contour plot of the plane and 120 mm explosives, respectively, where fragments impacted explosive charges with a velocity of 2469.4 m/s, impact polar angle of 90°, and azimuth angle of 60°. It can be found that the shock wave intensity in the plane and 120 mm is almost the same at 1 us, and the shock pressure of both explosives subsequently decreased slightly due to the influence of rarefaction waves from the boundary. Ultimately, theplane charge was initiated and the shock wave transited to a detonation wave at 6 us, while the shock wave pressure decreased and less explosive was reacted in 120 mm explosive charge. The smaller the radius of the explosive charge, the earlier the shock wave was affected by the rarefaction wave from the boundary. Figure 6a, b are the recorded pressure histories of gauges inside explosives for plane and 120 mm charges, respectively. The initial shock wave pressures in two charges generated by the impact of fragments with the same velocity were both 16.6 GPa. Then the shock wave pressure in the 120 mm charge decreased along the gauge path, indicating that the explosive was not shock initiated. On the other hand, the initial shock wave of plane charge decreases slowly due to the delayed arrival of rarefaction waves. As more explosives were ignited by the shock wave, the shock wave pressure increased to 17.3 GPa at 4 μs and eventually grew to a stable detonation wave at 6 μs.

By comparing the velocity results of the first column in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, it can be found that when the azimuth angle φ is 90°, the detonation threshold velocities of the explosive charges under the same polar scenario hardly changed as the different cylindrical radii changed. For example, the detonation threshold velocities of explosives with different radii are almost the same when φ is 90° and θ is 30°, indicating that the variables of polar angle θ and radius r were independent of each other. Qualitative analysis showed that when the azimuth angle was fixed and the polar angle changed, the shape of the velocity vector was a plane. The intersection surface of the velocity vector plane and the explosive charge with different radii was still a plane. Hence, for charges with different radii, the time difference for the stress wave to reach the free boundary and be reflected as a rarefaction wave was small. Hence, the detonation threshold velocities were hardly affected by the charge radius.

For the explosive charge with the same radius, the detonation threshold velocity would change when one variable of the azimuth and polar angle was fixed and the other variable was changed, indicating that the azimuth angle φ and the polar angle θ were correlated. The direction of the velocity vector would change when any one variable of the azimuth angle or polar angle changed, resulting in different times for the shock wave to reach the boundary, leading to a change in detonation threshold velocity.

Three-dimensional initiation criterion

With the analysis above, azimuth angle φ was correlated with polar angle θ and charge radius r, while polar angle θ and radius r were independent of each other. The following increment function of the detonation threshold velocity of the explosive charge was established according to the correlation between variables:

The values of velocity increment function f(δ) of Tables 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 could be obtained with Eq. (3). To simplify the process of establishing the model, the influence of parameters in Eq. (7) on the threshold velocity increment is discussed separately. Firstly, the values of partition function f(cosφ, cosθ) were set to 0 when θ = 90°. Then the increment function f(δ) was equal to f(cosφ, d/r), and the threshold velocity increment curves with different radii as a function of azimuth angle can be obtained, as shown in Fig. 7. It can be seen from Fig. 7 that the threshold velocity increment increased as the radius decreased.

To obtain the expression of f(cosφ, d/r), the threshold velocity increment of different radii was normalized according to the following equation.

where fg is the normalized velocity increment value, fmax(cosφ, d/r) is the maximum value of f(cosφ, d/r) for different radii. The normalized curves are shown in Fig. 8, where the normalized velocity increment curves of different radii almost overlap. Hence, the five curves are averaged to obtain the velocity increments independent of the radius, and the relationship between fg and cosφ was obtained using the fitting function of Matlab, as shown below.

The comparison of normalized velocity increment and fitted function is shown in Fig. 8, where good agreement can be observed.

The values of fmax(cosφ, d/r) for different radii are shown in Fig. 9, which are modeled into the following function:

Figure 9 illustrated the comparison between the maximum velocity increment and the model of fmax(cosφ, d/r), where good agreement can also be observed. Hence, the expression of f(cosφ, d/r) can be obtained as follows by combining Eqs. (9) and (10).

The value of f (cosφ, cosθ) can be obtained by subtracting f(cosφ, d/r) from f(δ):

Figure 10a–e sketched the threshold velocity increment curves of function f (cosφ, cosθ) with polar angles for different radii according to Eq. (12), where no correlation can be found between two variables. Hence, the velocity increment values were averaged to obtain the velocity increments independent of the radius, as shown in Fig. 10f.

It can be seen from Fig. 10f that the values of the vertical axis increased exponentially as the value of cosθ increased. Besides, when the polar angle was the same, the values of f(cosφ, cosθ) increased with the increase of the azimuth angle. With the above curve characteristics, the following function was used to describe the curve:

where a, b, c, and, d are undetermined constants, φ0 is the reference azimuth. The optimal parameter solutions in Eq. (13) were determined with the genetic algorithm (stochastic parallel search algorithms based on the principles of natural selection and genetics) and listed in Table 7. The comparison between the simulation results of and the mathematical model established is shown in Fig. 11, where the solid and dashed lines represent the velocity increments for averaged radius and mathematical model, respectively. It can be seen that the simulation results agree well with the mathematical model.

The three-dimensional initiation criterion considering the polar angle, azimuth angle, and charge radius was established as follows by combining Eqs. (4), (7), (11), and (13).

The comparison between the threshold velocity increment calculated by the three-dimensional initiation criterion and the simulation results is shown in Fig. 12. It can be found that for explosive charges with different radii, the difference between the threshold velocity increment predicted by the three-dimensional criterion and the numerical calculations is small, and the maximum error is 3.09%, indicating that the accuracy of the three-dimensional initiation criterion is high.

Conclusion

The detonation threshold velocities of Comp B explosive charges with different radii under the fragment impact at different polar angles and azimuth angles were obtained by numerical calculations. A three-dimensional initiation criterion was established by analyzing the correlation between variables. The main conclusions are summarized as follows:

-

(1)

When the impact polar angle of the fragment is fixed, the detonation threshold velocity under the same azimuth angle scenario increases as the radius of the charge decreases. However, when the impact azimuth angle of the fragment is fixed, the detonation threshold velocity under the same polar angle scenario is almost unaffected by the charge radius.

-

(2)

Based on the u2d criterion and correlation between variables, a three-dimensional initiation criterion was established considering the influence of polar angle, azimuth angle, and charge radius. The criterion developed can predict the threshold impact velocity of the fragment to initiate an explosive charge with different radii at any angle. The results indicated that the maximum error between the three-dimensional initiation criterion and simulation results is 3.09%.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Dickinson, D. L. & Wilson, L. T. The effect of impact orientation on the critical velocity needed to initiate a covered explosive charge. Int. J. Impact. Eng. 20, 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0734-743X(97)87495-7 (1997).

Gruau, C. et al. Ignition of a confined high explosive under low velocity impact. Int. J. Impact. Eng. 36, 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijimpeng.2008.08.002 (2009).

Liu, R. & Chen, P. W. Modeling ignition prediction of HMX-based polymer bonded explosives under low velocity impact. Mech. Mater. 124, 106–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mechmat.2018.05.009 (2018).

Ma, D., Chen, P., Zhou, Q. & Dai, K. Ignition criterion and safety prediction of explosives under low velocity impact. J. Appl. Phys. 114, 113505. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4821431 (2013).

Gustavsen, R. L., Sheffield, S. A. & Alcon, R. R. Measurements of shock initiation in the tri-amino-tri-nitro-benzene based explosive PBX 9502: Wave forms from embedded gauges and comparison of four different material lots. J. Appl. Phys. 99, 114907. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2195191 (2006).

Li, M. et al. Shock initiation of covered flake JH-2 high explosive by simultaneous impact of multiple fragments. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 45(7), 1133–1140. https://doi.org/10.1002/prep.201900366 (2020).

Georgevich, V., Pincosy, P. & Chase, J. High explosive detonation threshold sensitivity due to multiple fragment impacts. UCRL-CONF-201762 (2004).

Mader, C. L. & Pimbley, G. H. Jet initiation and penetration of explosives. J. Energ. Mater. 1(1), 3–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370658308010817 (1983).

Bahl, K. L., Vantine, H. C. & Weingart, R. C. The shock initiation of bare and covered explosives by projectile impact. UCRL-83872 (1981).

Ma, D. et al. Effects of specimen size on impact-induced reaction of high explosives. Combust. Sci. Technol. 185, 1227–1240. https://doi.org/10.1080/00102202.2013.782012 (2013).

Chidester, S. K., Tarver, M. & Lee, C. G. Impact ignition of new and aged solid explosives. In AIP Conference Proceeding, vol. 429 707–710 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.55669.

Dai, X., Wen, Y., Huang, H., Zhang, P. & Wen, M. Impact response characteristics of a cyclotetramethylene tetranitramine based polymer-bonded explosives under different temperatures. J. Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4820248 (2014).

Leus, V., Ceder, R., Ognev, V. & Mayseless, M. The role of tangential velocity in explosive initiation by fragment impact. Def. Technol. 18, 2190–2197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dt.2022.04.016 (2022).

Wang, X., Jiang, J., Wang, S. & Men, J. Detonation threshold velocity calculation model of cylindrical covered charge impacted by fragment. Explos. Shock Waves 39(1), 012302. https://doi.org/10.11883/bzycj-2017-0271 (2019).

Held, M. Discussion of the experimental findings from the initiation of covered, but unconfined high explosive charges with shaped charge jets. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 12, 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/prep.19870120507 (1987).

Fan, Z. et al. Displacement and stress response of open-web girders under near field explosive loading. Sci. Rep. 14, 30782. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-80915-z (2024).

Li, C. et al. Field test and numerical research on explosion crater in calcareous sand. Sci. Rep. 14, 25626. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-75737-y (2024).

Lee, E. L. & Tarver, C. M. Phenomenological model of shock initiation in heterogeneous explosives. Phys. Fluids 23(12), 2362–2372. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.862940 (1980).

Murphy, M. J. Lee, E. L. Weston, A. M. & Williams, E. A. Modelling shock initiation in composition B. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Detonation Symposium (Office of Naval Research, 1993).

Meyers, M. A. Dynamic Behavior of Materials 126–140 (Wiley, 1994).

Johnson, G. R. & Cook, W. H. Fracture characteristics of three metals subjected to various strains, strain rates, temperatures and pressures. Eng. Fract. Mech. 21(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-7944(85)90052-9 (1985).

Century Dynamics Inc. AUTODYN material library, Version17.0. (Century Dynamics Inc., 2016).

James, H. R. & Hewitt, D. B. Critical energy criterion for the initiation of explosives by spherical projectiles. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 14, 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1002/prep.19890140602 (1989).

Held, M. Initiation criteria of high explosives at different projectile or jet densities. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 21, 235–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/prep.19960210505 (1996).

Acknowledgements

This paper is supported by the opening project of State Key Laboratory of Explosion Science and Safety Protection (Beijing Institute of Technology) under Grant No. KFJJ24-02M and Jiangsu Funding Program for Excellent Postdoctoral Talent.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hao Cui: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, validation, writing—original draft. Junan Wu: investigation, writing—review. Yuxin Xu: writing—review. Pu Song: writing—review, validation, supervision. Rui Guo: conceptualization, supervision; Writing—review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, H., Wu, J., Xu, Y. et al. Critical velocity criterion of explosive charges initiated by fragment impact considering impact angle and charge radius. Sci Rep 15, 28116 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08750-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08750-4