Abstract

Cultivation of honeysuckle, Lonicera japonica, irrigated with brackish-water, represents a new way to exploit saline–alkali land in the Yellow River Delta. However, how L. japonica responds to brackish-water irrigation is not clear. Biomass allocation, carbon–nitrogen stoichiometry, and carbon and nitrogen storage in L. japonica under four brackish-water irrigation treatments (T0: 0 mm, T40: 40 mm, T80: 80 mm, T120: 120 mm) were examined. Brackish-water irrigation significantly affects tissue biomass and the proportions of roots and stems in L. japonica. Root, stem, and leaf biomass increase with increased amount of brackish-water irrigation. The proportion of root biomass decreases significantly with increased brackish-water irrigation, root and leaf C contents increase, and stem and leaf N contents decrease. The proportion of root C storage trends downward with increased brackish-water irrigation, but the curve is concave for the proportion of root N storage. Root, stem, and leaf biomass correlate significantly with C and N contents, and C:N ratios for the three organs, excepting leaf C contents. Our results suggested that T120 is more conducive to the biomass accumulation of L. japonica, and promotes the C content of most organs, but reduces their N content. These findings improve our understanding of the response of L. japonica to brackish-water irrigation, demonstrate that brackish-water irrigation is a viable technique to save water in irrigation, and identify a new use for saline–alkali land in the Yellow River Delta.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Saline–alkali land occurs widely, globally, and has limited agricultural value1,2,3,4. Saline soils have soluble salt contents ≥ 0.6%, whereas alkaline soils contain > 20% of the total cation exchange of exchangeable sodium ions and a pH > 95. Saline–alkali agriculture occurs in saline–alkali soils, and requires adaptive soil, water and crop management practices. Such agriculture mitigates land resource shortages, ensures food security, and positively affects the economy in saline–alkali areas6,7,8,9. Screening of saline–alkali tolerant economic crops and water-saving irrigation is therefore important for agricultural development9,10,11,12,13,14. Brackish-water irrigation, and planting of the saline–alkali tolerant honeysuckle Lonicera japonica represent potentially important strategies for the use of saline–alkali land in the Yellow River Delta15.

Brackish-water irrigation—the use of water of salinity of 2–5 g L−1, is important for agricultural development in saline–alkali land12,16,17. By altering the soil water-salt balance, this form of irrigation creates adequate soil conditions for plant growth, alleviating soil salinization, increasing soil micronutrient contents, promoting plant growth18,19. Brackish-water irrigation also helps mitigate a shortage of freshwater resources, and moderates soil degradation20. This irrigation mode directly affects the distribution of moisture in the soil, and its salinity, and influences groundwater quality in irrigation areas through infiltration16,19,21. Furthermore, salinity stress not only induces ion toxicity but also reduces the osmotic potential of the soil solution, effectively creating a physiological drought that restricts water availability to roots. This osmotic imbalance compromises root hydraulic conductivity, thereby limiting water uptake capacity22,23.

Lonicera japonica, one of 38 valuable medicinal herbs in China, is a perennial, semi-evergreen species, that grows in both woody and vine varieties15,24,25,26. The root, stem, leaf, flower, and seeds of this plant all have traditional medicinal applications, such as for clearing heat and detoxification, and cooling and dispersing wind-heat11,13,14,27. This species can be planted to construct and restore landscapes28. The well-developed root system of this species can improve soil structure, and its high stem and leaf density increase high canopy coverage. This species, which prefers neutral and alkaline sandy loam soils, can survive in extreme saline–alkali environments with salinities of 0.56% and pH 8.2. It can do so because the plants enhanced their root respiration to produce more ATP for energy supply, helping to maintain normal cellular function. The energy can be used to (1) synthesize osmoregulatory substances (such as proline and soluble sugars), helping plants maintain cellular osmotic balance and alleviate osmotic stress caused by salinity; to (2) operate ion pumps and increase Na+ efflux capacity, helping plants eliminate excess sodium ions, absorb potassium ions, maintain intracellular ion balance, and alleviate salt stress29,30. Moreover, a high salinity press can trigger the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, leading to cell damage. Plant improved root respiration can enhance the activity of antioxidant enzymes, eliminate reactive oxygen species, and reduce oxidative damage15. Previous studies reported that root respiration provides intermediate products for other metabolic processes, helping plants maintain normal metabolism in high salt environments and enhance stress resistance to adapt to the saline–alkali environment26. Additionally, suitable soil moisture conditions contribute to denser growth and high yields. Thus, L. japonica is a good species to plant for soil and water conservation and soil salinization management.

Combined modes of irrigation methods (direct irrigation with brackish water, alternating irrigation with brackish water and fresh water, drip irrigation), brackish-water treatment techniques (magnetized water-treatment, desalination, solar desalination, and electrodialysis technologies), and supporting management measures (surface cover, soil conditioner) can improve the growth and yield of crops such as cotton, wheat, goji berries, watermelons, tomatoes, lettuce, rice, and grapes3,16,18,19,20,31,32. For example, Mu et al. found that inoculation with H. crustuliniforme substantially enhanced the salinity stress resistance of L. japonica33; Hu reported L. japonica to exhibit adaptive abilities in low salt-stress environments, though with increased salt concentration and prolonged stress, photosynthesis and growth were inhibited34; and He et al. reported drought stress to inhibit photosynthesis, and to induce more serious photoinhibition and oxidative stress than iso-osmotic salt stress15. However, little is known of how L. japonica responds to brackish-water irrigation, limiting the use of this species for water-saving and efficient agricultural use of saline–alkali land in the Yellow River Delta.

We compare the biomass allocation, C,N stoichiometry and corresponding carbon and nitrogen storage in L. japonica following exposure to different volumes of brackish water, to: (1) determine if biomass allocation of L. japonica varies with brackish water irrigation volume; (2) if brackish water irrigation volume affects the C, N stoichiometry and corresponding storage; and (3) how biomass allocation of L. japonica is influenced by C, N stoichiometry. We hypothesized that: (1) the biomass allocation of L. japonica would first increase and then decrease with increased brackish water irrigation volume; (2) a larger volume of brackish-water would reduce C and N contents and their corresponding storage; and (3), that the C,N stoichiometry of L. japonica was closely related to the change in biomass allocation. We aim to improve the understanding of the economic characteristics of L. japonica, how it can be used to exploit saline–alkali land, the development of new sources of irrigation water, and serve the water saving and high-quality agricultural development in the Yellow River Delta.

Materials and methods

Experimental site

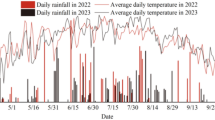

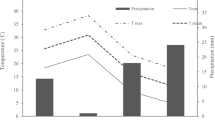

The study area is located in the Yellow River Delta in the northeastern of Shandong province in China (37°20′–38°10′N, 118°17′–119°10′). The saline alkali land in the Yellow River Delta is heavy, abundant, and widely distributed. The area of saline alkali land is about 443,000 hectares, accounting for more than half of the total regional area. Among them, the coastal saline alkali land area reaches 236,000 hectares. In recent years, the proportion of heavy saline alkali land in the Yellow River Delta decreased, while the proportion of light saline alkali land increased. The annual average temperature is 12.68 ℃, the average annual rainfall is 602.98 mm, and the average annual evaporation rate is approximately 1962 mm. In the past few decades, the annual average temperature in the Yellow River Delta has shown an increasing trend, while the annual precipitation has shown a continuous decreasing trend, indicating a significant warming and drying trend in the region. The precipitation in the Yellow River Delta is uneven throughout the year, with mostly dry periods from April to June. Due to strong evaporation, shallow groundwater can be transported to the surface, causing salt accumulation and easily forming a dry and saline alkali environment. The 70% of precipitation is mainly concentrated in July and August, and heavy rainfall can easily lead to surface flooding and waterlogging15,26.

Plant materials and experimental design

Two-year old L. japonica (Beihua No. 1) were collected from Jiujianpeng Agricultural Technology Limited Company (Pingyi, Shangdong, China), and cultivated in a habitat island demonstration zone in the Yellow River Delta Ecological Research Station of Coastal Wetland, Chinese Academy of Sciences (37°46′6″N, 118°58′9″E).

Before planting, the experimental area was divided into 16 plots of 4 m × 3 m (length × width), each of which was irrigated with fresh water for surface soil desalination, and to which cow dung was applied as a bottom fertilizer (application rate of 200 kg·hm−2) to improve soil fertility. Robust L. japonica seedings showing consistent growth were selected and planted in experimental plots in May 2019. Plants were spaced at 1 m intervals, with 1 m between rows (12 plants plot−1). Diammonium phosphate fertilizer (40 kg·hm−2) was applied to each plot, which was also irrigated with fresh water. Any withered L. japonica seedlings were replaced. Field management was carried out by applying cow dung, weeding, and killing pests during the experimental period.

Initial soil electric conductivity (EC), pH, and sodium adsorption ratio (SAR) values in experimental plots were 2.27 dS·m−1, 7.75 and 7.95, respectively. Initial soil total nitrogen, carbon, nitrate nitrogen, ammonium nitrogen, available phosphorus, and available potassium contents were 0.20 g·kg−1, 12.46 g·kg−1, 2.31 mg·kg−1, 17.03 mg·kg−1, 107.79 mg·kg−1, and 107.79 mg·kg−1, respectively. The pH, conductivity and salinity of experimental irrigation (brackish) water ranged 8.21–8.89, 4.17–5.19 dS·m−1, and 2.31–2.88‰, respectively.

Four irrigation treatments were established: a control group (T0), representing rain-fed conditions with no additional irrigation, and three treatment groups irrigated with 40 mm (T40), 80 mm (T80), and 120 mm (T120) of brackish water irrigation volume (Fig. 1). Each treatment was replicated four times, and randomly positioned within the experimental area. Irrigation was performed on June 25, July 29, and September 27 of 2019, and April 29, and June 20 of 2020. Irrigation water volume was controlled by a water meter. The average value of soil water content, soil electric conductivity and soil water potential during experiments were shown in Table 1.

Plant biomass and biomass allocation

After two years, L. japonica grew well without any death or obvious withering (excluding death during the normal life cycle) due to brackish-water irrigation treatments. In October 2020, the leaf, stem, and root of two representative L. japonica plants per plot were sampled in each treatment. Above-ground plants portions were gathered and then divided into leaves and stems. Root tissues within the confines of the 30 cm × 30 cm plot, to a depth of 40 cm, were collected. Leaf, stem, and root samples were placed into individual-labelled paper bags, and oven-dried at 60 °C to constant weight, then weighed. The mean value of the two samples from each plot was calculated. Plant biomass and the percent of biomass allocation for root, stem, and leaves were calculated as follows:

where Pb, Rb, Sb, and Lb are plant, root, stem, and leaf biomass (g), respectively; Obr is the percentage of organ biomass, and Ob is plant organ biomass (root, stem, leaf).

Plant C and N content, storage and allocation proportion

Dried root, stem, and leaf samples were ground and filtered through a 60-mesh (250 μm) sieve before determining C and N contents by the elemental analyzer (Elementar Vario Micro, Germany). The C and N storage of root, stem, and leaf samples per plant was calculated as follows:

where \({S}_{C/N}\) is C or N storage per plant; \({C}_{C/N}\) is C or N content; \({Sr}_{C/N}\) is the percent of C or N storage within a plant organ; and \({S}_{C/N}^{P}\) is C or N storage for the L. japonica plant.

Statistical analyses

The biomass, biomass allocation proportion, C and N contents, C:N ratio, C and N storage, and proportion of C and N in root, stem and leaf samples were checked for normality and homogeneity. One-way ANOVA was used to test the effects of brackish-water irrigation on plant biomass, biomass allocation proportion, ecological stoichiometry of C and N, and the storage and allocation proportion of C and N using Duncan test at the 0.05 significance level when assumptions of homoscedasticity were met. A permutational analysis of variance (ANOVA) was implemented in R software (using the lmPerm package) when assumptions of homoscedasticity were not met for some indicators (leaf biomass, the proportion of stem biomass, stem C content, root C:N, root C storage per plant, stem C storage per plant, leaf C storage per plant, leaf N storage per plant, plant N storage per plant, stem C allocation, leaf C allocation, stem N allocation, leaf N allocation). Correlation analysis for any two indicators of plant traits was performed using Pearson correlation with two tailed test in SPSS software.

Results

Biomass allocation

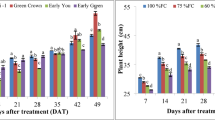

Significant differences in root, stem, leaf, and total biomasses were recorded in different treatments (Fig. 2a, Table S1). Root, stem, leaf, and total biomasses increased with increasing brackish-water irrigation, with peak values for root (124.86 g), stem (469.17 g), and leaf (235.53 g) biomass recorded in T120, and minimum root (29.35 g), stem (41.57 g) and leaf (23.12 g) biomass reported for T0. Total biomass ranged 94.05–829.56 g, with the highest (T120) being 8.82 times greater than the lowest (T0).

Effect of brackish-water irrigation on root, leaf, stem, and total biomass within a plant (a), and their corresponding proportions (b) in different organs of Lonicera japonica (n = 4, Mean ± SE). Different letters stand for significant differences in the four treatments at the same plant tissue, and indicate significant differences at the 0.05 significance level. T0 means rain-fed conditions with no additional irrigation; T40, T80, and T120 mean the treatment groups irrigated with 40 mm, 80 mm, and 120 mm of brackish water irrigation volume, respectively.

Brackish-water irrigation significantly affected the proportions of root and stem biomass per plant (Fig. 2b, Table S1). The proportion of root biomass decreased from 31.18% (T0) to 15.17% (T120). Stem biomass per plant accounted for 44.11–55.61% of total biomass, with the lowest proportion in T0 (17.60% lower than T80, 19.17% lower than T40, and 21.95% lower than T120). Leaf biomass per plant accounted for 24.52–29.75% of total biomass, with no significant difference among treatments.

Carbon and nitrogen ecological stoichiometry, storage, and allocation proportions

Carbon and nitrogen ecological stoichiometry

Brackish-water irrigation significantly affected root and leaf C contents (Fig. 3a, Table S1). Root C content in T40, T80, and T120 ranged 40.18–43.19%, and was significantly higher than T0 (30.71%). Leaf C content ranged 41.04–43.60%, and was lowest in T0. There were no significant differences in stem C content among treatments.

Effect of brackish-water irrigation on carbon (a) and nitrogen contents (b), and the C:N ratio (c) in Lonicera japonica (n = 4, Mean ± SE). Different letters stand for significant differences in the four treatments at the same plant tissue, and indicate significant differences at the 0.05 significance level. T0 means rain-fed conditions with no additional irrigation; T40, T80, and T120 mean the treatment groups irrigated with 40 mm, 80 mm, and 120 mm of brackish water irrigation volume, respectively.

Brackish-water irrigation significantly affected root and stem N contents (Fig. 3b, Table S1). The highest value, 1.13% (T40), was 1.42 times higher than that for T80 (0.79%). Stem N content decreased from 1.06% (T0) to 0.78% (T120).

Brackish-water irrigation significantly affected the C:N ratio in roots (Fig. 3c, Table S1). This ratio increased with increased irrigation, peaking at 52.40 in T120 (1.64 times of the minimum value 32.04); root C:N ratios were 35.87 in T40 and 51.48 in T80.

C and N storage per plant

Significant differences in root, stem, leaf and plant carbon storage within a plant occurred among treatments (Fig. 4a, Table S1). Root, leaf, stem, and plant carbon storage within a plant increased with increasing irrigation, and peaked in T120. The lowest plant carbon storage (35.5 g) recorded in T0 was 9.9% of the T120 value (360.3 g).

Effect of brackish-water irrigation on carbon (a) and nitrogen storage (b) of Lonicera japonica (n = 4, Mean ± SE). Different letters stand for significant differences in the four treatments at the same plant tissue, and indicate significant differences at the 0.05 significance level. T0 means rain-fed conditions with no additional irrigation; T40, T80, and T120 mean the treatment groups irrigated with 40 mm, 80 mm, and 120 mm of brackish water irrigation volume, respectively.

There were significant differences in root, stem, leaf, and plant nitrogen storage within a plant among treatments (Fig. 4b, Table S1). All indicators increased with increasing irrigation, with the highest values in root, stems, and leaves nitrogen storage within a plant (1.07 g, 3.63 g, 3.25 g, and 7.95 g, respectively) in T120, being 3.78, 8.24, 6.14, and 6.35 times the corresponding lowest values in T0.

C and N allocation proportion

Brackish-water irrigation significantly affected the allocation of carbon to roots (Fig. 5a, Table S1), which decreased with increasing irrigation. The highest recorded value (25.19%) occurred in T0, and the lowest (15.07%) occurred in T120. In T80, this ratio in roots (16.40%) differed marginally (by 1.33%) from the lowest value of 15.07% (T120). No significant difference was observed in carbon allocation ratios in stems and leaves among treatments.

Effects of brackish-water irrigation on carbon (a) and nitrogen allocation (b) in roots, stems, and leaves of Lonicera japonica (n = 4, Mean ± SE). Different letters stand for significant differences in the four treatments at the same plant tissue, and indicate significant differences at the 0.05 significance level. T0 means rain-fed conditions with no additional irrigation; T40, T80, and T120 mean the treatment groups irrigated with 40 mm, 80 mm, and 120 mm of brackish water irrigation volume, respectively.

Brackish-water irrigation significantly affected nitrogen allocation in roots (Fig. 5b, Table S1), which ranged 11.71% (T80) to 22.43% (T0), and decreased with increased irrigation in T0, T40, and T80, and then increased in T120. No significant differences in nitrogen allocation for stem and leaf samples were found among treatments, the nitrogen allocation of these organs being higher than that of roots.

Correlation analysis

The four biomass indicators (root, stem, leaf, and plant) correlated positively with root and stem C contents, and the C:N ratios of the three organs (root, stem, leaf), and negatively with the N content of the three organs (Table 2). The proportion of root biomass correlated negatively with C and N contents, and the C:N ratios of the three organs, except for stem C and root N contents. The proportion of stem biomass was correlated positively with root C content and leaf C:N ratio, and negatively with leaf N content. The proportion of leaf biomass did not significantly correlate with C or N contents, or the C:N ratios of the three organs.

Discussion

Biomass allocation provides insights into the way that plants allocate resources among organs, which reflects their response to environmental fluctuations, and adaptive mechanisms35,36,37. Leaf biomass of L. japonica decreased with increased salt stress25. Additionally, root, stem, and leaf biomass of L. japonica decreased with increased severity of salt stress, with the effect of salt stress on underground biomass more pronounced than on above-ground portions38. Compared with variation in the proportion of root biomass, the biomass allocation to stems and leaves changed slightly, consistent with previous studies25,39. Furthermore, drought intensifies the effect of salinity on plant growth. Previous studies found that photosynthesis was more susceptible to drought stress than iso-osmotic salt stress in L. japonica according to drought-induced greater decrease in photosynthetic rate15, and then affect plant biomass. Naturally, L. japonica experiences seasonal droughts in saline-alkali land in the Yellow River Delta, and brackish water irrigation can reduce the salt content of cultivated soil and increase soil trace elements. While alleviating drought, it can promote plant growth and increase plant yield and quality40. Lonicera japonica prevents drought-induced tremendous leaf water loss upon iso-osmotic salt stress, and had a capacity to dispose accumulated Na+. Furthermore, The dramatic biomass increase observed between T0 and T120 may arise from the combined effects of osmotic stress (due to salinity) and drought-induced hydraulic limitations during early growth stages (T0). Under salinity, reduced osmotic potential in the rhizosphere exacerbates water deficits, impairing root hydraulic conductivity and delaying recovery22,41. This aligns with studies showing that co-occurring salt and drought stresses synergistically reduce water uptake efficiency, leading to transient growth suppression followed by compensatory biomass accumulation as plants acclimate23. Therefore, it is important to examine the growth of L. japonica under salt-stress and drought conditions and find effective irrigation methods for L. japonica.

The positive correlation between L. japonica biomass and brackish-water irrigation volume contradicts previous findings25,38. This is inconsistent with hypothesis (1), possibly because of the large amount and high frequency of brackish-water irrigation, which transports salts in surface soils to deeper layers, reducing the overall soil salinity. Brackish-water irrigation satisfies the water requirements for L. japonica, and promotes its growth and biomass26,42. Increasing soil salinity may reduce above-ground and increase below-ground biomass of plants38,43. Contrary to these findings, L. japonica when exposed to more brackish-water irrigation grew larger, and more vigorously, and because plants invested more resources in above-ground portions, the proportion of the root biomass reduced in brackish-water treatments compared with the control (T0). Thus, brackish-water irrigation changed biomass allocation of L. japonica, and influenced overall plant physiology and growth (plant biomass allocation, plant morphology, photosynthesis, etc.).

Carbon and nitrogen play crucial roles in ecosystem cycles and multi-element balance process7,43,44,46,47. The C:N ratio in plants directly affects the formation and transformation of photosynthetic products, protein synthesis, and nutrient uptake48,49. Numerous studies have demonstrated salt stress to adversely affect both carbon and, especially, nitrogen metabolism in plants24,50,51 . Prolonged salt stress can cause the accumulation of excessive soluble sugars in leaves, which impede NO3− and NH4+ uptake by roots and reduce leaf photosynthesis43. Consequently, plant nitrogen metabolism decreases, hindering the storage of carbon and energy, and inhibiting plant growth43,52. We report brackish-water irrigation to significantly promote root and leaf C contents, and the root C:N ratio of L. japonica, and to reduce stem and leaf N contents compared with T0. This indicates a high synthesis capacity of C-related substances in corresponding organs, and a reduced synthesis capacity of N-related substances with brackish-water irrigation. This may be related to the dilution of nitrogen within the plant because of rapid growth30. These results may indicate adaptation to salt-stressed environments, with regulation of C and N across different parts of the plant to support growth and metabolic activities33,50. Additionally, consistent with changes in plant biomass, C and N storage in L. japonica increased with increasing brackish-water irrigation. Similar C and N allocation strategies have been reported for L. japonica under environmental stress. Reduction of root C and N storage indicates a high investment of C and N in above-ground plant parts.

It is necessary to understand the relationship between biomass allocation and C-N stoichiometry to understand the response of plant growth to varied brackish-water irrigation, and to establish optimal irrigation volumes18,24,35,48. We report a strong correlation between plant biomass and C-N stoichiometry, except for leaf C contents. Because leaves are the main site of photosynthesis, they transfer C to stems and roots, which can create a mismatch between leaf C content and the biomass of three organs35,39. We also report all biomass indicators to increase with increased root and stem C contents (other than leaf C content), indicating that plant roots and stems are more obedient in biomass allocation strategies, while leaves, as the main source of biomass accumulation, have initiative and flexibility in biomass allocation strategies25,44. Because data were acquired at the end of the growth period, we speculated that plants mainly accumulate substances, and reduced enzyme activity in their bodies53, resulting in a negative relationship between plant N content and biomass indicators. The C:N ratio affects C and N contents in the three organs to regulate biomass, and decreases the proportion of root biomass. The proportion of leaf biomass was not significantly related to C-N stoichiometry, indicating the initiative and flexibility of leaves in biomass allocation strategies.

Lonicera japonica naturally experiences seasonal droughts in saline–alkali land in the Yellow River Delta15,26. Brackish-water irrigation may satisfy the water demands of this species, the planting of which improves the use-efficiency of saline–alkali land15,29,32,54. Previous studies have reported different irrigation methods on the growth, physiological response, and quality of L. japonica, but little was known of how the C-N stoichiometry of this species responded to brackish-water irrigation15. We previously reported that contrast photosynthesis, photoinhibition and oxidative stress of L. japonica under moderate and severe iso-osmotic salt and drought stresses15. Based on the above experiment and findings, we investigate brackish-water irrigation for L. japonica in a condition of the deficiency of fresh water in the coastal zone. A larger irrigation amount of brackish water (120 mm) improves the growth and biomass of L. japonica. However, further investigation is required to determine the effects of brackish-water irrigation volume on plant quality. Increasing the brackish-water irrigation volume strengthens seedlings of this species, and lays the foundation for subsequent quality improvement.

Conclusion

Brackish-water irrigation significantly affects organ biomass, and their corresponding proportions in L. japonica, excepting leaf biomass. Increased brackish-water irrigation significantly increases organ and plant biomass, but decreases the proportion of root biomass. Brackish-water irrigation also promotes the C content of three organs (except for stem C content under T40) and reduces the N content (except for root N content under T40). Both C and N storage in L. japonica was promoted, and increased like biomass. The proportion of root C and N storage with brackish-water irrigation decreases compared to the control (T0). Biomass indicators correlate positively with C content (except for leaf C content) and C:N ratio of the three organs, but negatively with N content. These findings explain the responses of biomass allocation, C, N stoichiometry and their corresponding storage of L. japonica to brackish-water irrigation, support water saving irrigation, and identify a new agricultural use for saline–alkali land in the Yellow River Delta.

Data availability

Data available on request from authors (Zhang Dongjie, E-mail: zhangdongjie14@126.com).

References

Baloch, M. Y. J. et al. Utilization of sewage sludge to manage saline-alkali soil and increase crop production: Is it safe or not?. Environ. Technol. Innov. 103266 (2023).

Ma, C. et al. Saline-alkali land amendment and value development: Microalgal biofertilizer for efficient production of a halophytic crop-Chenopodium quinoa. Land Degrad. Dev. 34(4), 956–968 (2023).

Wang, Y., Chen, Y., Sun, Z. & Sun, W. The structural characteristics and driving mechanism of collaborative innovation network for saline–alkali land development in China. Land Degrad. Dev. 34(15), 4667–4679 (2023).

Xie W. et al. Saline soil organic matter characteristics of aggregate size fractions after amelioration through straw and nitrogen addition. Land Degradation & Development 34, 2098-2109 (2023).

Zhang, P., Hou, X. & Wang, J. Causes and amelioration measures of Saline-alkali land in Xinjiang region. Mod. Agric. Sci. Technol. 24, 178–180 (2017) (in Chinese).

Du, Y., Liu, X., Zhang, L. & Zhou, W. Drip irrigation in agricultural saline-alkali land controls soil salinity and improves crop yield: Evidence from a global meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 880, 163226 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Ecosystem service value evaluation of saline—alkali land development in the Yellow River Delta—the example of the Huanghe Island. Water 15(3), 477 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Application of biochar and organic fertilizer to saline-alkali soil in the Yellow River Delta: Effects on soil water, salinity, nutrients, and maize yield. Soil Use Manag. 38(4), 1679–1692 (2022).

Cui, L. et al. Revitalizing coastal saline-alkali soil with biochar application for improved crop growth. Ecol. Eng. 179, 106594 (2022).

Cao, Y., Song, H. & Zhang, L. New insight into plant saline-alkali tolerance mechanisms and application to breeding. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(24), 16048 (2022).

Li, R. et al. Molecular mechanism of saline-alkali stress tolerance in the green manure crop Sophora alopecuroides. Environ. Exp. Bot. 210, 105321 (2023).

Li, W., Wang, Z., Zhang, J., & Zong, R. Soil salinity variations and cotton growth under long-term mulched drip irrigation in saline-alkali land of arid oasis. Irrig. Sci. 1–11 (2021).

Li, Y. L. et al. Effects of waterlogging and elevated salinity on the allocation of photosynthetic carbon in estuarine tidal marsh: a mesocosm experiment. Plant Soil 482(1–2), 211–227 (2023).

Li, Y., Xie, L., Liu, K., Li, X. & Xie, F. Bioactive components and beneficial bioactivities of flowers, stems, leaves of Lonicera japonica Thunberg: A review. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 106, 104570 (2023).

He, W. et al. Contrasting photosynthesis, photoinhibition and oxidative damage in honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica Thunb.) under iso-osmotic salt and drought stresses. Environ. Exp. Bot. 182, 104313 (2021).

Wei, K., Zhang, J., Wang, Q., Guo, Y. & Mu, W. Irrigation with ionized brackish water affects cotton yield and water use efficiency. Ind. Crops Prod. 175, 114244 (2022).

Zhao Y. et al. A review on the optimization of irrigation schedules for farmlands based on a simulation–optimization model. Water 16, 2545 (2024),

Pang, H. C., Li, Y. Y., Yang, J. S. & Liang, Y. S. Effect of brackish water irrigation and straw mulching on soil salinity and crop yields under monsoonal climatic conditions. Agric. Water Manag. 97(12), 1971–1977 (2010).

Yin, C. Y. et al. Desalination characteristics and efficiency of high saline soil leached by brackish water and Yellow River water. Agric. Water Manag. 263, 107461 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Assessment of water quality ions in brackish water on drip irrigation system performance applied in saline areas. Agric. Water Manag. 289, 108544 (2023).

Zhang, Z., Zhang, Z., Lu, P., Feng, G. & Qi, W. Soil water-salt dynamics and maize growth as affected by cutting length of topsoil incorporation straw under brackish water irrigation. Agronomy 10(2), 246 (2020).

Baca, C. J. C. et al. Root hydraulic properties: An exploration of their variability across scales. Plant Direct 8(4), e582 (2024).

Fricke, W., Bijanzadeh, E., Emam, Y. & Knipfer, T. Root hydraulics in salt-stressed wheat. Funct. Plant Biol. 41(3), 366–378 (2014).

Fan, L., Chen, L., Ding, R., Wang, L. & Zhang, B. Geographical discrimination of honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica Thunb.) from China by characterization of the stable isotope ratio and multielemental analysis. Anal. Lett. 51(16), 2509–2518 (2018).

Yan, K., Wu, C., Zhang, L. & Chen, X. Contrasting photosynthesis and photoinhibition in tetraploid and its autodiploid honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica Thunb.) under salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 227 (2015).

Yan, K. et al. Deciphering salt tolerance in tetraploid honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica Thunb.) from ion homeostasis, water balance and antioxidant defense. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 195, 266–274 (2023).

Tian, J., Che, H., Ha, D., Wei, Y. & Zheng, S. Characterization and anti-allergic effect of a polysaccharide from the flower buds of Lonicera japonica. Carbohydr. Polym. 90(4), 1642–1647 (2012).

Shen, S., Yao, Y. & Li, C. Quantitative study on landscape colors of plant communities in urban parks based on natural color system and M-S theory in Nanjing, China. Color Res. Appl. 47(1), 152–163 (2022).

Yan, K., Cui, M., Zhao, S., Chen, X. & Tang, X. Salinity stress is beneficial to the accumulation of chlorogenic acids in honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica Thunb.). Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1563 (2016).

Yan, K., Zhao, S., Bian, L. & Chen, X. Saline stress enhanced accumulation of leaf phenolics in honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica Thunb.) without induction of oxidative stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 112, 326–334 (2017).

Bustan, A. et al. Effects of timing and duration of brackish irrigation water on fruit yield and quality of late summer melons. Agric. Water Manag. 74(2), 123–134 (2005).

Ma, K., Wang, Z., Li, H., Wang, T. & Chen, R. Effects of nitrogen application and brackish water irrigation on yield and quality of cotton. Agric. Water Manag. 264, 107512 (2022).

Mu, D. et al. Growth and physiological mechanism study of H. crustuliniforme and Lonicera japonica symbiotic relationship under salt tolerance. J. Shandong Univ. Nat. Sci. 59(1), 139–150 (2024) (in Chinese).

Hu, A. et al. Effect of NaCl stress on the growth and photosynthetic physiological characteristics of honeysuckle seedlings. Jiangsu Agric. Sci. 47(11), 170–173 (2019) (in Chinese).

Puglielli, G., Laanisto, L., Poorter, H. & Niinemets, Ü. Global patterns of biomass allocation in woody species with different tolerances of shade and drought: evidence for multiple strategies. New Phytol. 229(1), 308–322 (2021).

Zhang, C. & Xi, N. Precipitation changes regulate plant and soil microbial biomass via plasticity in plant biomass allocation in grasslands: a meta-analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 614968 (2021).

Bai Y., et al. Soil moisture impact on biomass partitioning and relative chlorophyll content for legume grass mixtures in a controlled environment. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research 21(1), 439-450 (2023).

Li, S. Physiological analysis of salt-tolerant honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) and its amelioration functions in addition to exogenous K2SiO3∙nH2O, Nanjing Agricultural University. (2015). (in Chinese)

Schierenbeck, K. A., Mack, R. N. & Sharitz, R. R. Effects of herbivory on growth and biomass allocation in native and introduced species of Lonicera. Ecology 75(6), 1661–1672 (1994).

Chen, S., Shao, L., Sun, H., Zhang, X. & Li, Y. Effect of brackish water irrigation on soil salt balance and yield of both winter wheat and summer maize. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 24(8), 1049–1058 (2016) (in Chinese).

Kaneko, T. et al. Dynamic regulation of the root hydraulic conductivity of barley plants in response to salinity/osmotic stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 56(5), 875–882 (2015).

Zhu, J., Yang, M., Sun, J. & Zhang, Z. Response of water-salt migration to brackish water irrigation with different irrigation intervals and sequences. Water 11(10), 2089 (2019).

Xie, L. The effects of water and salt factors on soil microorganisms and carbon allocation in the plant soil systems in coastal salt marsh (East China Normal University, 2022) (in Chinese).

Cao, Y. et al. The effects of different nitrogen forms on chlorophyll fluorescence and photosystem II in Lonicera japonica. J. Plant Growth Regul. 42(7), 4106–4117 (2023).

Liu, Z. et al. Effects of cadmium stress on carbon sequestration and oxygen release characteristics in a landscaping hyperaccumulator—Lonicera japonica Thunb. Plants 12(14), 2689 (2023).

Zhang, D. et al. Effect of hydrological fluctuation on nutrient stoichiometry and trade-offs of Carex schmidtii. Ecol. Ind. 120, 106924 (2021).

Wright, I. J. et al. The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 428(6985), 821–827 (2004).

Liu, R. & Wang, D. C: N: P stoichiometric characteristics and seasonal dynamics of leaf-root-litter-soil in plantations on the loess plateau. Ecol. Ind. 127, 107772 (2021).

Jiang, P., Chen, Y. & Cao, Y. C: N: P stoichiometry and carbon storage in a naturally-regenerated secondary Quercus variabilis forest age sequence in the Qinling Mountains, China. Forests 8(8), 281 (2017).

Yan, K., Xu, H., Zhao, S., Shan, J. & Chen, X. Saline soil desalination by honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica Thunb.) depends on salt resistance mechanism. Ecol. Eng. 88, 226–231 (2016).

Cui, G. et al. Response of carbon and nitrogen metabolism and secondary metabolites to drought stress and salt stress in plants. J. Plant Biol. 62, 387–399 (2019).

Huang, L. et al. Ameliorating effects of exogenous calcium on the photosynthetic physiology of honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) under salt stress. Funct. Plant Biol. 46(12), 1103–1113 (2019).

Zhang, D. et al. Physiological responses of Carex schmidtii Meinsh to alternating flooding-drought conditions in the Momoge wetland, northeast China. Aquat. Bot. 153, 33–39 (2019).

Wang, T., Xu, Z. & Pang, G. Effects of irrigating with brackish water on soil moisture, soil salinity, and the agronomic response of winter wheat in the Yellow River Delta. Sustainability 11(20), 5801 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2022QD152; ZR2024MD072); the Youth Innovation Support Program of Shandong Universities (No. 2023KJ273); the PhD research startup foundation of Binzhou University (No. 2021Y25; No. 2021Y14) and College Student Innovation Training Program Plan (S202410449034).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

He Wenjun, Zhang Dongjie and Wang Xiaojie designed the study; Liu Xuepeng, Xie Mengting, He Wenjun, Li Tongtong, Wen Shu collected the data of Lonicera japonica; Liu Xuepeng, He Wenjun, Zhang Dongjie, Zhang Mingye drafted the manuscript and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xuepeng, L., Mengting, X., Shu, W. et al. Effects of brackish water irrigation on biomass allocation and carbon, nitrogen stoichiometry in Lonicera japonica. Sci Rep 15, 23972 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08769-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08769-7