Abstract

This study delves into the relationship between goal orientation and scientific creativity, crucial for driving innovation and solving complex challenges. Drawing on goal orientation theory and situated expectancy-value theory, we investigated how different goal orientations influence scientific creativity among 248 university researchers. The findings indicate that both learning and performance approach goals significantly enhance scientific creativity through knowledge collaboration. Additionally, the strength of perceived work-related stressors modulates this relationship; stronger perceptions of these stressors intensify the positive effects of learning and performance goals on creativity. The study contributes to theoretical understandings in several ways. First, it expands on how goal orientation influences creativity within scientific domains. Second, it sheds light on the role of stress as a catalyst in scientific creativity. Finally, it links stressor perspectives to organizational behaviour literature, providing valuable insights for organizational managers. These insights suggest that promoting learning and performance-oriented goals may be especially beneficial in environments where researchers encounter significant stressors, enhancing their creative outputs in public research institutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Scientific creativity plays a crucial role in addressing contemporary challenges and opportunities that shape societal sustainability1,2. It is typically defined as the intellectual ability or capacity to produce scientifically novel and socially valuable results in the context of scientific tasks3,4. In recent years, scholars have increasingly focused on exploring the factors that enhance creativity, with a growing emphasis on goal orientation theory1,5.

Goal orientation theory, particularly its distinction between learning goal orientation and performance goal orientation, offers valuable insights into the cognitive and social demands inherent in scientific creativity6,7. Learning goal orientation involves striving to develop personal capabilities by acquiring new knowledge and skills, aligning with the cognitive demands of scientific creativity by encouraging curiosity, exploration, and new approaches to complex scientific challenges8,9. In contrast, performance goal orientation is driven by the desire to demonstrate competence through favorable evaluations and avoid negative assessments, and it can impact the social dynamics of scientific creativity, influencing how individuals collaborate, compete, and engage with their peers in scientific evaluative settings10,11. Therefore, these orientations not only shape an individual’s motivation but also profoundly influence their creative performance, especially in complex and collaborative fields12,13. By understanding how these orientations affect both individual cognition and social dynamics, goal orientation theory provides a nuanced framework for exploring scientific creativity.

While goal orientation theory has been widely applied across various domains, its specific impact on scientific creativity remains unclear1,14. Existing research indicates that individual behavior serves as a key mediator between goal orientation and creativity, with behaviors often involving independent information processing and contextual perceptions1,5. In today’s rapidly evolving research environments, it is increasingly challenging for individuals to tackle complex scientific problems alone. Knowledge collaboration has thus become a critical factor in fostering scientific creativity15. Knowledge collaboration, defined as voluntary helping each other to achieve common or private goals of knowledge creation by pooling together diverse expertise and perspectives16,17, can pool complementary resources, accumulate academic capital18,19, and stimulate innovative thinking15.

In this study, we view knowledge collaboration as a mediator in the relationship between goal orientation and scientific creativity. Specifically, we propose that an individual’s goal orientation (especially learning and performance orientations) influences scientific creativity through the facilitation of knowledge collaboration. In complex research environments, Researchers with a learning goal orientation and a performance-approach goal orientation actively seek knowledge collaboration with other knowledge holders in order to acquire knowledge, enhance their skills, and demonstrate their achievements20,21. In turn, knowledge collaboration effectively integrates specialized expertise and resources, providing individuals with more opportunities for creative problem-solving22,23, and thus enhancing personal academic development24,25.

Nevertheless, the impact of goal orientation on scientific creativity is not static; environmental factors, particularly the perceived intensity of work-related stress events, may play a significant moderating role in this relationship. According to the Situated Expectancy-Value Theory (SEVT), individual behaviors and performance are dynamically influenced by the context, especially in response to stressors26,27. This study posits that the perceived intensity of work stress events moderates the relationship between goal orientation and knowledge collaboration, ultimately influencing scientific creativity. A stronger perception of stress may amplify or diminish the beneficial effects of goal-oriented behaviors on scientific creativity by enhancing or hindering knowledge collaboration.

By integrating goal orientation theory, SEVT, and the perspective of knowledge collaboration, this research provides a multidimensional framework to explain how goal orientation influences scientific creativity through knowledge collaboration and how the perception of work stress moderates this process. This framework offers a novel perspective on understanding creativity in scientific research, as well as practical implications for how to effectively manage goal orientations, foster knowledge collaboration, and address work-related stress in academic and organizational settings.

Literature review and hypotheses

An important characteristic of goal orientation is that it shapes individuals’ mental frameworks, influencing how they interpret and respond to situations7. This study focuses on learning goal orientation (hereafter, “learning goal”) and performance approach goal orientation (hereafter, “performance approach goal”), opting not to include performance avoidance goal for several reasons. First, performance avoidance goals are generally considered maladaptive, having been shown to negatively relate to motivation and performance outcomes28. Second, the process of knowledge creation requires dialectical thinking, as the dominant paradigms shaping scientific research are inherently imperfect29. The dissemination of scientific knowledge is intended to provoke contemplation and stimulate new ideas among researchers. Thus, excessive concern about mistakes and negative evaluations within scientific research is deemed unnecessary.

The SEVT proposes that individuals, when making decisions, consider their anticipated goals, evaluate the likelihood of achieving these goals through specific actions (i.e., expectancy), and assess the value of the outcomes26,30. Expectancy refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to successfully complete an activity. Value refers to how worthwhile and useful an activity is perceived, influencing engagement and goal-directed behaviors26. Value is further categorized into utility value, attainment value, intrinsic value, and cost26,30.

Individual goal orientation and knowledge collaboration

Knowledge collaboration is recognized as one of the most critical behaviors for effective scientific research15,24. The evidence of a rapid rise in knowledge collaboration over the last century contributed to its rise and increased individuals’ expectancy of collaborative success15. Influenced by goal orientation, individuals develop distinct perceptions of the value of knowledge collaboration, which in turn guide and dictate their collaborative behavior6.

A learning goal motivates individuals to develop their competence and skills by enactive mastery7,31. Those oriented towards learning are driven by intrinsic factors31, such as the desire to acquire knowledge and skills and the pursuit of opportunities and challenges to develop competence7. Knowledge collaboration provides a platform for knowledge exchange, deepening the understanding through exposure to diverse perspectives and experiences. Engaging with diverse viewpoints and experiences in collaborative environments helps individuals deepen their insights and expand their personal knowledge, aligning with the goals of enhancing knowledge acquisition and competence15,24,32. So, learning-oriented individuals are willing to engage in knowledge collaboration, recognizing its role in facilitating mastery and ability development, despite the potential cost investment required33,34.

H1a: Individual learning goal is positively related to knowledge collaboration.

Individuals with a performance approach goal aim to demonstrate high ability by gaining favorable evaluations and outperforming peers7,10. Such individuals often gauge their competence against normative standards31. In the realm of scientific academia, the publication of research findings serves as a primary criterion for assessing individuals’ capabilities35. To outperform peers and garner favorable evaluations, individuals have to produce scholarly outcomes, thereby earning recognition from particular colleague groups36. This necessitates effective strategies for knowledge creation, such as knowledge collaboration19. Moreover, knowledge collaboration offers selective incentives or rewards, including access to complementary resources, academic capital, and high impact15,37. Patterns of preferential attachment indicate that individuals tend to attach themselves to more reputed collaborators or those with greater resources, thereby attracting attention to their own work19. Such selective incentives make knowledge collaboration a dominant strategy, maximizing individual gains37, and enhancing their performance and demonstrating their competence38.

H1b: Individual performance approach goal is positively related to knowledge collaboration.

Knowledge collaboration and individual scientific creativity

Knowledge collaboration creates an ideal context of knowledge creation by uniting individuals with diverse information, social networks, and skills15,24,39. In these settings, individuals act as brokers, enhancing knowledge circulation and sparking inspiration across domains. This facilitates the cross-fertilization of ideas and the combination of different knowledge elements into innovative and practical outcomes25,40. Additionally, the variety of ideas and contexts to which individuals are exposed can be easily converge during collaborative work, allowing members to build on each other’ ideas and potentially ignite a surge of novel ideas39. This process aligns with the principles of social constructivism, which suggests that individuals construct their own knowledge and develop cognitively through social collaboration41. This dynamic is especially apparent in public scientific research, where tasks often require the integration of diverse knowledge to generate original ideas and solve complex problems15,42 What’s more, the rational division of labor among individuals with diverse knowledge, beliefs, and skills in collaboration settings is seen as a catalyst for scientific creativity40,43. In summary, knowledge collaboration enables researchers to leverage specialization in the deep stock of knowledge while at the same time gaining the benefits of breadth to enhance scientific creativity.

H2: Knowledge collaboration positively influences individual scientific creativity.

Currently, Hypothesis 1 substantiates the influence of individual goal orientation on knowledge collaboration behavior. Knowledge collaboration, in turn, impacts individual scientific creativity, serving as a mediating factor in the relationship between individual goal orientation and scientific creativity.

H3a: Individual learning goal has an indirect positive relationship, via knowledge collaboration, with individual scientific creativity.

H3b: Individual performance approach goal has an indirect positive relationship, via knowledge collaboration, with individual scientific creativity.

Moderating role of perceived work stressful events strength

The competitiveness within public research organizations stems from the principles governing resource allocation, reward systems, and the evaluation of scientific performance44,45. Individuals compete for limited resources and recognition based on their contributions to advancing scientific knowledge. Such competitive pressures create a stressful environment where securing funding, prestige, and career progression becomes paramount36.

A strong focus on learning goals emerges as a crucial internal drive31, predicting active coping and sustained motivation in the face of challenge and stress46. This belief strengthens an individual’s attention to intrinsic values, emphasizing the satisfaction derived from deepening knowledge and solving problems. Consequently, Through the integration of knowledge and reflective learning, individuals with a learning goal continuously expand their cognitive boundaries47,48. They adopt a process-oriented self-evaluation standard. Even in the face of failure or conflict, they attribute it to an opportunity for improvement, maintaining ongoing motivation for exploration49,50. As a result, they exhibit greater resilience when confronted with high-pressure work events31,51. When perceived work stress increases, the intrinsic value-driven mechanisms of learning goal-oriented individuals may become more pronounced. They maintain positive expectations, demonstrate greater perseverance, and seek further challenges that offer learning opportunities31,52,53.

According to the SEVT, although high stress increases the costs of resource investment (such as time and energy), individuals with a strong learning goal orientation can effectively offset external barriers like low success expectations through their high subjective value placed on personal growth54,55. They tend to reframe stressful events as learning challenges and employ strategies such as knowledge collaboration and systematic reflection to deepen cognitive integration56. This process helps maintain, or even accelerate, the enhancement of creativity. Thus, even under significant work-related stress, individuals with a strong learning goal will actively engage in knowledge collaboration, which in turn enhances individual scientific creativity and strengthens the indirect relationship between learning goals and scientific creativity.

H4a: The perceived work stressful events strength positively moderates the indirect relationship of individual learning goal with individual scientific creativity via knowledge collaboration such that the indirect relationship is stronger when perceived work stressful events strength is higher.

In contrast, individuals who adopt a high-performance approach focus on external value, socially comparative standards of outcome51,53. While this tendency predicts increased effort expenditure and persistence, it is also linked to surface-level processing and the experience of negative emotions such as anxiety, perceived threats, and avoidance of help-seeking behaviors10,53. As a result, their behavioral strategies exhibit a pronounced outcome-oriented characteristic, often relying on existing knowledge frameworks for surface-level processing57. These characteristics make individuals with a performance goal orientation more prone to maladaptive motivational patterns, particularly under conditions of stress or when faced with signals of potential challenges.

In high-pressure environments, the defensive motivational patterns of performance goal-oriented individuals exacerbate the decline in creativity. Due to their reliance on external value and evaluation standards, they are more likely to perceive the need for knowledge collaboration as a signal of inadequate capability7,58, leading them to avoid behaviors associated with knowledge-sharing and knowledge collaboration. Moreover, stressful events amplify their sensitivity to cost-benefit considerations, such as time loss and coordination difficulties, which in turn lowers their expectations for successful knowledge collaboration while motivating them to prioritize conservative strategies in order to maintain their image of competence15,39. Therefore, under stress, these individuals are less likely to increase their efforts through knowledge collaboration, weakening the indirect relationship between performance goal orientation and scientific creativity, particularly under conditions of high perceived stress.

H4b: The perceived work stressful events strength negatively moderates the indirect relationship of individual performance approach goal with individual scientific creativity via knowledge collaboration such that the indirect relationship is weaker when perceived work stressful events strength is higher.

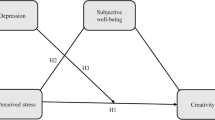

Figure 1 depicts our model.

Method

Sample and data collection

The research setting for this study was universities in China, where are key public research organizations driving basic innovation, societal progress and economic development through knowledge creation59,60. Given their pivotal role, the scientific creativity of university researchers is deemed essential as it underpins knowledge creation.

The survey, conducted in Chinese, followed a rigorous translation and back-translation procedure to ensure accuracy61. Initially crafted in English, the survey questions were translated into Chinese by one translator and then back-translated into English by another. Discrepancies between the two English versions were meticulously addressed before finalizing the Chinese version.

Data collection occurred in two phases over two months, from October to December 2023, to examine the temporal relationships among the variables. In the first phase, participants completed an online questionnaire assessing individual goal orientation, perceived work stressful events strength, and knowledge collaboration (Time 1). Four weeks later, they filled out a second questionnaire on individual scientific creativity (Time 2), using an anonymous code they had generated at Time 1 to ensure matching. Participation was voluntary, with confidentiality assured. Respondents were explicitly encouraged to answer honestly, as noted in the introductory message of the questionnaire, to mitigate social desirability bias62.

Out of 500 distributed surveys, 410 responses were received, of which 248 indicated that they had experienced work-related stress events during the survey period and provided complete responses. The response rate for complete surveys was 49.6%. This study conducts empirical analysis based on these 248 complete questionnaires. Among the respondents, 54.0% were female, and 58.1% were from Project 211 universities (top-tier universities in China). The participants varied in academic rank, including professors (10.5%), associate professors (18.2%), lecturers (26.6%), assistant teachers (5.2%), and Ph.D. candidates (39.5%).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures were performed in compliance with the principles outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions, as well as the relevant ethical guidelines and regulations. The experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tianjin University. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians prior to their inclusion in the study.

Measures

The measures of the five focal constructs utilized Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”).

Individual goal orientation. Individual learning goal was measured by Brett & VandeWalle’s (1999) five-item scale (sample item: “I am willing to select a challenging work assignment that I can learn a lot from”), and individual performance approach goal was measured using VandeWalle’s (1997) four-item measure (sample item: “I’m concerned with showing that I can perform better than my coworkers”). The coefficient alphas for the learning goal and the performance approach goal were 0.84 and 0.85, respectively.

Knowledge collaboration. Knowledge collaboration was measured using the adapted version of So & Brush’s (2008) scale, with the referent changed from collaborative learning online to knowledge collaboration. Sample items include “I feel part of a learning community in a group” and “I actively exchange my ideas with others”. The coefficient alpha was 0.87.

Individual scientific creativity. Individual scientific creativity was assessed by a 3-item scale following Hoever et al. (2023). The measurement of creativity in Hoever et al. (2023) includes the core characteristics of “scientific creativity,” namely novelty and usefulness, both of which require creative thinking as well as the ability to identify and solve problems. Given the credibility and recognition of this established scale, we made slight adjustments to the wording of the items in Hoever et al. (2023) to better suit the context of scientific research, thus deriving the items used in this study to measure scientific creativity. Sample items include “I often come up with creative solution to research problems” and “I often come up with new and practical ideas for the research.” The coefficient alpha was 0.78.

Perceived work stressful events strength. Initially, each participant was asked to recall whether they had encountered any exogenous work-related stress events that occurred between April 2023 and September 2023. Based on event system theory, participants who reported experiencing such stress events subsequently rated the intensity of the event using an 11-item scale covering three dimensions: novelty, disruption, and criticality63. An example from the four-item event novelty scale is “There is a clear, known way to respond to this event” (reverse coded), with a Cronbach’s of 0.81. A sample item from the three-item event criticality scale is “This event is critical for the long-term success of me,” which had a Cronbach’s of 0.79. The event disruption scale included items such as “This event disrupts my ability to get its work done,” achieving a Cronbach’s of 0.82.

Furthermore, a second-order confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed, demonstrating that each item loaded significantly onto its corresponding dimensions. These dimensions also loaded onto an overall second-order factor that measured perceived work stressful events strength. This model exhibited good fit (χ2/df ratio = 1.71, NFI = 0.94, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.05). The combination of all three dimensions determines the overall “strength” of an event64. So, the dimensions were averaged to derive a composite strength value score for each event, with an overall Cronbach’s alpha for perceived work stressful events strength being 0.78.

Control variables. Age and gender were controlled as variables due to their significant influence on collaborative behaviors in scientific community65,66. Females were coded as 1 and males as 0. Age was categorized into five levels: 1 for “Under 31”, 2 for “31–40”, 3 for “41–50”, 4 for “51–60”, and 5 for “over 60”. Additional control measures included individual reputation and institutional tier, recognizing that senior scientists and elite researchers at prestigious institutions are often more engaged in collaborative science39,66. Furthermore, substantial differences exist among various institutions in academia67,68. Academic title, a key indicator of a researcher’s reputation35, was thus segmented into five categories: 5 for “Professor”, 4 for “Associate Professor”, 3 for “Lecturer”, 2 for “Assistant Teacher”, and 1 for “Ph.D. candidate”. The reputation of universities, especially those involved in China’s Project 211, was also considered69. Because universities listed in Project 211 enjoy higher policy priority and obtain more research funding from the government, which may have significant influence on researchers’ scientific performance of these institutions68. A binary variable represented institutional tier, coded as 1 for universities affiliated with Project 211 and 0 otherwise.

Reliability and validity

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to examine the factor structure of our models. The full model exhibited good fit [χ2/df ratio = 1.01, NFI = 0.92, CFI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.04, RMSEA = 0.01]. Each construct demonstrated significant factor loadings, high average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) values, surpassing the thresholds of 0.50 and 0.70 respectively, confirming good convergent validity and internal consistency. Discriminant validity was validated as the square root of AVE (shown on the diagonal in Table 1) exceeded the inter-construct correlations70.

Potential common method bias (CMB) was addressed through multiple analyses. Harman’s single-factor test did not indicate a predominant factor, with the first factor explaining only 16.72% of the variance. A confirmatory factor analysis model combining all items into a single factor performed poorly (e.g., χ2/df ratio = 7.61, NFI = 0.38, CFI = 0.41, RMSEA = 0.16), suggesting low risk of CMB. Furthermore, comparing models with and without a common latent factor confirmed the absence of significant CMB, as models including the latent factor did not significantly differ in fit (e.g., χ2/df ratio = 0.99, NFI = 0.93, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.001) from those without it62. Thus, these results collectively indicate that CMB was not a concern in our study.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations are shown in Table 2. To address potential concerns about multicollinearity affecting the precision of the regression models, a multicollinearity diagnosis was conducted. This analysis indicated that the variance inflation factor (VIF) scores were below 5 and tolerance statistics exceeded 0.10, confirming that collinearity was not a concern.

Relationships of individual goal orientation, knowledge collaboration and individual scientific creativity

Variables were systematically introduced into the model in blocks. Hierarchical regression results, detailed in Table 3, investigated the relationships between goal orientations and knowledge collaboration. Table 4 shows the hierarchical regression results of the relationships between goal orientations and individual scientific creativity. The results of model 2 in Table 3 show that individual learning goal (β = 0.230, p < 0.05) and performance approach goal (β = 0.210, p < 0.05) are significantly related to knowledge collaboration, thereby supporting H1a and H1b. Further, the results of model 6 in Table 4 indicate that knowledge collaboration positively correlates with individual scientific creativity (β = 0.277, p < 0.01), supporting H2.

H3a postulated that individual learning goal would positively influence individual scientific creativity indirectly through knowledge collaboration. The findings from model 2 in Table 3 confirm that individual learning goal significantly relates to knowledge collaboration (β = 0.230, p < 0.05). A significant positive relationship between individual learning goal and individual scientific creativity is evidenced in model 7 of Table 4 (β = 0.332, p < 0.01). Knowledge collaboration significantly relates to individual scientific creativity (model 6, Table 4). The bootstrap test, with 5000 sub-samples, confirmed the significance of this indirect relationship, with an indirect effect of 0.058 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) ranging from 0.018 to 0.114, which did not include zero. These results affirm the indirect relationship posited in H3a.

H3b suggested that individual performance approach goal would also have a positive indirect relationship with individual scientific creativity via knowledge collaboration. The results of model 2 in Table 3 show that individual performance approach goal significantly influences knowledge collaboration (β = 0.210, p < 0.05). Model 9 in Table 4 indicates a positive relationship between performance approach goal and individual scientific creativity (β = 0.220, p < 0.05). The bootstrapping test revealed an indirect effect of 0.049 with 95% CI between 0.011 and 0.101, not including zero. This result validates the significant indirect relationship hypothesized in H3b.

Indirect relationships moderated by perceived work stressful events strength

H4a posited that perceived work stressful events strength would strengthen the indirect relationship between individual learning goal and scientific creativity though knowledge collaboration. Although the interaction between individual learning goals and perceived work stressful events was not statistically significant in the initial model (model 4, Table 3: β = 0.214, n.s.), further analysis revealed nuanced effects. A bootstrap test (5000 sub-samples) was conducted to explore this moderation at the first stage of the mediation pathway71. The moderated mediation effect was 0.065 with a 95% CI of (0.002, 0.138), not containing zero (Table 5). The simple slope analysis showed that the indirect relationship that individual learning goal had with individual scientific creativity via knowledge collaboration was significant at high (simple slope = 0.090, 95% CI = [0.034, 0.161]) and average (simple slope = 0.058, 95% CI = [0.018, 0.114]) levels of perceived work stressful events strength, but not at low levels (simple slope = 0.026, 95% CI = [−0.019, 0.088]). This differential effect across levels supported H4a.

H4b predicted that that higher perceived work stressful events would weaken the indirect relationship between individual performance approach goal and scientific creativity through knowledge collaboration. Contrary to expectations, the interaction term in model 4, Table 3 (β = 0.311, p < 0.10) indicated a significant positive effect, suggesting strengthening rather than weakening of the relationship at higher levels of stress. The moderated relationship is plotted in Fig. 2.

Further analysis using moderated path analytic procedures revealed a moderated mediation effect of 0.086 with a 95% CI of [0.020, 0.175] (Table 5), indicating statistical significance. The simple slope analysis corroborated these findings, showing significant effects at high (simple slope = 0.091, 95% CI = [0.035, 0.167]) and average (simple slope = 0.049, 95% CI = [0.011, 0.101]) stress levels, but not at low stress levels (simple slope = 0.006, 95% CI = [−0.045, 0.061]). The results from the bootstrap tests confirmed that the relationship between individual performance approach goals and scientific creativity, moderated by perceived work stressful events, was indeed stronger at higher stress levels, thus Hypothesis 4b was not supported.

Discussion

Our research discovered that both individual learning goals and performance approach goals positively influence scientific creativity through knowledge collaboration. Notably, this effect is moderated by the strength of perceived work-related stressful events; a stronger perception of stress amplifies the indirect positive relationship between these goals and individual scientific creativity.

This study places the goal orientation theory within a distinct context—scientific research—and examines the impact mechanism of individual differences in goal orientation on scientific creativity. The research indicates that an individual’s goal orientation is crucial, as it exerts an indirect positive influence on scientific creativity through knowledge collaboration. Lim and Shin (2021) found that learning orientation has an inverted U-shaped relationship with individual performance, emphasizing that excessive learning goal orientation can hinder personal performance8. However, in the context of scientific creativity within research communities, the situation appears to be different. Personal learning goal orientation can help individuals unlock their full potential, enhancing creativity knowledge acquisition, capacity improvement and work engagement9,33. Empirical evidence regarding performance-approach goal orientation reveals a mixed set of positive and negative motivational outcomes31,72. This study reports the positive outcomes of performance-approach goal orientation on the scientific creativity of researchers in the research community. Individuals with a high-performance goal orientation tend to compare their achievements with those of others, striving to demonstrate their skills and abilities. This drive fosters healthy competition among scholars. Furthermore, a performance goal orientation enhances the practical utility of creativity by triggering cognitive closure, thereby improving an individual’s creativity12.

The relationship between individual goal orientation and knowledge creativity is mediated by knowledge collaboration. This resonates with and extend the work of Zhang et al. (2020), who explored the mediating role of personal information elaboration in the relationship between learning goals and individual creativity. However, unlike learning goals, performance-approach goal orientation is unrelated to information elaboration5. This study reveals that the creative effects of different goal orientations may operate through another cognitive and social exchange mechanism—knowledge collaboration. Scientific research is a highly collaborative activity due to the complexity of scientific problems and the limitation of resources15. Collaborating with others can reduce the inevitable costs of learning and mastering new domain-specific knowledge73. Goal orientations facilitate individual scientific creativity by fostering positive value perceptions through knowledge collaboration74,75. Therefore, the motivation behind engaging in creative actions can be understood as the expectation to satisfy needs for knowledge and challenges (learning goal orientation) or work meaning (performance-approach goal orientation)38,76.

The perceived work stressful events strength moderates the impact of individual goal orientation on scientific creativity. It is commonly believed that stress is detrimental, as stressful events deplete cognitive resources, leading to emotional exhaustion and diminishing an individual’s initiative64,77. However, some studies have indicated that stress can produce favorable outcomes. This is because some forms of stress are associated with challenging work experiences, which prompt individuals to reflect on problems, further promoting innovative behavior78. We argue that researchers with different goal orientations may have different attitudes toward stress and views on knowledge collaboration. Thus, we hypothesize that perceived work stressful events strength will have opposing moderating effects on the relationships between learning/performance approach orientation and scientific creativity through knowledge collaboration, as individual goals reflect differentiated motivations. However, the statistical findings indicate that perceived work stressful events strength has similar effects on both relationships. The stronger the perceived work stressful events strength, the stronger the indirect effects of personal learning goal orientation and performance-approach goal orientation on scientific creativity through knowledge collaboration. This study examines the recent exogenous stress experienced by researchers, with most of the reported stress events being related to institutional evaluations, grant applications, and paper publications. These events have clear objectives or endpoints and are capable of motivating individuals, fostering personal growth, and improving work performance, thus being considered as challenge stressors. The positive moderating effect of perceived work stress event intensity suggests that these challenging work stressors can act as catalysts for knowledge creation in academia. Although the motivational bases and behavioral strategies of learning goal orientation and performance goal orientation fundamentally differ, high-intensity challenge stress events can amplify the effectiveness of creativity transformation in knowledge collaboration through shared contextual mechanisms.

For individuals with learning goal orientation, the strength of stress triggers deep processing motivation through challenge appraisal. They view stress as an opportunity for skill expansion, systematically integrating cross-domain insights (such as method transfer and theoretical coupling) in knowledge collaboration, thereby enhancing the novelty of solutions12,79. For individuals with performance goal orientation, work stress strength, on the other hand, stimulates instrumental cooperative behavior through competitive appraisal. In order to maintain their ability advantage in external evaluations (e.g., competing for research priority), they may selectively engage in high-reward knowledge collaborations (e.g., forming alliances with authoritative scholars), leveraging knowledge collaboration networks to quickly access scarce resources (e.g., data, equipment)80. Therefore, although the goals and motivations of the two groups differ (intrinsic growth vs. external competition), high-intensity stress events jointly enhance the marginal contribution of knowledge collaboration to creativity.

Moreover, the study found that the interaction between learning goal orientation and perceived strength of work stressors did not exhibit a significant direct effect on knowledge collaboration. However, perceived work stressful events strength positively moderated the indirect effect of learning goal orientation on scientific creativity through knowledge collaboration. One possible explanation is that the main effect of learning goal orientation on knowledge collaboration may have already reached a saturation point at the baseline level. Individuals with a learning goal orientation typically possess a stable intrinsic motivation for knowledge collaboration34, and their knowledge collaboration behaviors are driven by long-term developmental goals rather than by short-term fluctuations in situational stress. As such, increases in perceived stress strength may not further enhance their collaborative engagement. Nevertheless, during the stage of creative knowledge integration, heightened stress strength may facilitate the reorganization of cognitive resources, thereby improving the efficiency with which knowledge collaboration contributes to creativity. In other words, under high-stress conditions, learning-oriented individuals are more likely to mobilize deep-level cognitive resources—such as systematic reflection and cross-domain connections—to cope with challenges. This, in turn, enables them to transform prior collaborative outcomes into more novel and innovative solutions.

Finally, the study unexpectedly found that, under a performance-oriented goal framework, high perceived strength of work stressors facilitated the thriving development of knowledge collaboration. Individuals with a performance orientation typically prioritize social comparison and the demonstration of competence, with their collaborative decisions heavily influenced by competitive cues and the visibility of potential rewards in the environment20. In high-pressure contexts, performance-oriented individuals may perceive knowledge collaboration as a strategic tool for competition, selectively engaging in knowledge sharing or alliance formation in an effort to maximize their relative advantage within the stressful situation. Additionally, moderate levels of stress may activate extrinsic motivation in performance-oriented individuals (e.g., increased competition due to the scarcity of rewards), prompting them to enhance output efficiency through knowledge collaboration.

Theoretical contributions

First, this study extends goal orientation theory from traditional educational and work contexts to the field of scientific research, particularly when exploring the relationship between goal orientation and creativity, with knowledge collaboration as a mediating mechanism. On one hand, most existing research on goal orientation theory has primarily focused on its impact on work or task performance within educational and organizational settings1,5. This study innovatively applies goal orientation theory to the research environment, examining how different types of goal orientations influence scientific creativity through knowledge collaboration. On the other hand, knowledge collaboration is an indispensable factor in scientific activities, especially in the context of scientific research15. Science sociology has highlighted that knowledge collaboration serves as an effective complement to independent learning, alleviating the burden of cumulative knowledge acquisition, providing diverse perspectives, and accumulating human and social capital80,81. However, in the context of scientific research, the role of knowledge collaboration—a behavior that is highly social and cognitive—in the relationship between goal orientation and individual scientific creativity has not been fully elucidated. By considering knowledge collaboration as a potential theoretical mechanism linking goal orientation and scientific creativity, this study further confirms the critical role of knowledge collaboration in today’s research environment. It also deepens our understanding of how goal orientation influences scientific creativity. This study contributes to the goal orientation theory by delineating an underlying theoretical mechanism—knowledge collaboration—that mediates the relationship between individual goals and scientific creativity in public research organizations.

Second, this study offers a perspective that reflects the value of work stress sources in scientific research, suggesting that the perception of work stress events can induce researchers to engage in more knowledge collaboration and thus improve their scientific creativity. It suggests that stress, often seen as a barrier to productivity, can also serve as a catalyst for creative outcomes when aligned with clear goal orientations. This can be explained from a cognitive perspective: most individuals tend to select behaviors that require lower cognitive effort, and this tendency is more pronounced under stress conditions82. Compared to knowledge learning, knowledge collaboration requires relatively lower cognitive effort and associated costs for individual researchers. This approach not only expands our understanding of contextual resources but also highlights additional conditions under which goal orientations can lead to enhanced scientific creativity. The combination of goal orientation theory and the situated expectancy-value theory provides a comprehensive theoretical framework, demonstrating that enhancing high learning goals and high performance-approach goals can establish individuals’ adaptability to stressful work environments, and the perceived costs associated with increased knowledge collaboration do not lead to additional negative impacts83.

Finally, the research integrates the stressor perspective with organizational behavior theories by linking perceived stress intensity with goal-directed behavior and scientific creativity. By integrating work stressful events and individual characteristics (i.e., goal orientations), our study responds to the growing call in the literature for a more comprehensive exploration of how individual traits and environmental factors coalesce to influence decision-making and performance outcomes63. This bridges a gap in the literature, offering a more nuanced understanding of how stressors can interact with individual characteristics to influence creative outputs, thereby enriching the organizational behavior discourse with a fresh perspective on stress management. Furthermore, this contribution lays the groundwork for future studies to further explore the nuanced roles of personal traits and stressors in shaping workplace behavior, offering valuable insights for both academic researchers and practitioners seeking to foster a more supportive and creative organizational environment.

Practical implications

Our research has several important managerial implications for practitioners involved in scientific research. (1) Enhancing Creativity through Goal Setting. Organizational managers, especially in public research institutions, are advised to promote and support both learning and performance approach goals among researchers. Research findings suggest that such goals not only enhance scientific creativity directly but also enable individuals to harness stressful situations to their advantage, thereby fostering an environment conducive to innovation. On one hand, task designs (e.g., interdisciplinary exploratory projects) and feedback mechanisms (e.g., progress-oriented assessments) should guide researchers to reconceptualize stress as an opportunity for personal growth rather than a mere tool for performance competition. On the other hand, for individuals who are naturally performance-oriented, it is necessary to implement transparent competitive rules and visible collaboration rewards (e.g., clear recognition of individual contributions in collaborative outcomes) to prevent them from falling into zero-sum games and social exclusion. Managers should regularly monitor the emotional exhaustion levels of high-performance-oriented individuals and reduce the risk of goal-ability misalignment through job crafting.

(2) Stress Management Strategies Based on Sources of Stress. Given that perceived work-related stress can amplify the positive impact of goal orientation on creativity, managers should consider developing stress management strategies that provide resource support (e.g., flexible funding allocation) and cognitive training (e.g., stress reframing workshops) to help researchers evaluate high-intensity events (e.g., research competitions) as controllable challenges, thereby stimulating exploratory behaviors in knowledge collaboration. Training programs that help researchers constructively perceive and utilize stress may be crucial. Simultaneously, establishing a stress source screening mechanism to identify and reduce unnecessary administrative burdens (e.g., redundant evaluation processes) and resource-depriving stressors (e.g., delays in equipment access) is essential, as these stress types directly undermine well-being without contributing to creativity.

(3) Policy development for supporting research innovation. Policy-makers in the scientific research domain should consider formulating policies that encourage knowledge collaboration and clear goal setting in stressful work conditions. Policies could include providing resources for collaborative projects, setting clear and attainable goals for research outcomes, and creating frameworks for effectively managing and utilizing work-related stress.

Limitations

First, all data in this study relied on self-reports, which may introduce mono-method bias. Although the measures used in our research showed reliability and validity and have also been drawn from existing scales that have been previously validated, further research is needed to replicate the results by using multisource data and to verify whether the results would be consistent.

Second, this study focused on the positive impact of learning and performance approach orientations on scientific creativity, excluding performance avoidance goals due to their generally maladaptive nature. However, the role of performance avoidance goals in scientific research, where failure and critical feedback may be integral for progress, merits consideration. Despite their negative association with motivation, these goals might influence researchers to adopt thorough approaches in high-stakes projects, possibly enhancing creativity in unexpected ways. The exclusion of performance avoidance goals from our analysis may overlook how a meticulous approach to avoiding failure could indirectly benefit scientific creativity. Future research could explore this dynamic, examining if there is a threshold where the fear of negative evaluations shifts from being detrimental to supportive of creativity, especially in complex research projects.

Third, this study did not examine whether the interplay between different type of individual goal orientation and the diversity in individual goal orientations is related to individual scientific creativity. An individual may concurrently pursue learning goal and performance approach goal, both of which collectively influence the expression of individual scientific creativity.

Fourth, these findings are based on data from researchers in public research organizations in China, which may not address the generalizability to organizations in different cultures. Although previous research has examined the indirect relationship between individual goal and creativity in other cultures, few studies have examined the mediator role of knowledge collaboration and dynamics boundaries. Thus, these relationships are needed to investigate within different cultural contexts to enhance our findings.

Finally, this study considers the intensity of perceived work stress events as an external situational factor, exploring its moderating role in the indirect relationship between goal orientation and scientific creativity. However, this assumption may oversimplify the dynamic interaction between goal orientation and stress appraisal. Individual assessments of stress events may be profoundly influenced by their goal orientation. Moreover, the potential bidirectional relationship between stress appraisal and goal orientation has not been captured in the model, which could weaken the rigor of causal inference. Future research could differentiate between the objective attributes of stress sources and individual appraisal tendencies through situational simulations, and use longitudinal tracking designs to independently measure dynamic changes in appraisal following stress events.

Conclusions

This study provides preliminary evidence that individual learning and performance approach goals are positively related to individual scientific creativity through knowledge collaboration. Furthermore, the strength of perceived work stressful events plays a moderating role, enhancing the relationships between individual learning and performance approach goals and individual scientific creativity (via knowledge collaboration). It is hoped that this investigation will spur further empirical research that merges innovation and stress management perspectives to provide evidence and strategies for the effective use of stressors in fostering innovation.

Data availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request. Requests for the data should be directed to Le Chang at clcassiel@163.com.

References

Gong, Y., Kim, T. Y., Lee, D. R. & Zhu, J. A multilevel model of team goal orientation, information exchange, and creativity. Acad. Manag J. 56, 827–851 (2013).

Valtonen, A., Kimpimäki, J. P. & Malacina, I. From Ideas to innovations: the role of individuals in Idea implementation. Creat Innov. Manag. 32, 636–658 (2023).

Xiang, S. et al. The interplay between scientific motivation, creative process engagement, and scientific creativity: A network analysis study. Learn. Individ Differ. 109, 102385 (2024).

Zhao, H., Zhang, J., Heng, S. & Qi, C. Team growth mindset and team scientific creativity of college students: the role of team achievement goal orientation and leader behavioral feedback. Think. Skills Creat. 42, 100957 (2021).

Zhang, J., Ji, M., Anwar, C. M., Li, Q. & Fu, G. Cross-level impact of team goal orientation and individual goal orientation on individual creativity. J. Manag Organ. 26, 677–699 (2020).

Elliot, A. J. & Church, M. A. A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance achievement motivation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 72, 218–232 (1997).

Vandewalle, D. Development and validation of a work domain goal orientation instrument. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 57, 995–1015 (1997).

Lim, H. S. & Shin, S. Y. Effect of learning goal orientation on performance: role of task variety as a moderator. J. Bus. Psychol. 36, 871–881 (2021).

Matsuo, M. Effect of learning goal orientation on work engagement through job crafting: A moderated mediation approach. Pers. Rev. 48, 220–233 (2018).

Senko, C. & Dawson, B. Performance-approach goal effects depend on how they are defined: Meta-analytic evidence from multiple educational outcomes. J. Educ. Psychol. 109, 574–598 (2017).

Mohd, S. Z., Iskandar, T. M., Monroe, G. S. & Saleh, N. M. Effects of goal orientation, self-efficacy and task complexity on the audit judgement performance of Malaysian auditors. Acc. Aud Acc. J. 31, 75–95 (2018).

Miron-Spektor, E. & Beenen, G. Motivating creativity: the effects of sequential and simultaneous learning and performance achievement goals on product novelty and usefulness. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 127, 53–65 (2015).

Miron-Spektor, E., Vashdi, D. R. & Gopher, H. Bright sparks and enquiring minds: differential effects of goal orientation on the creativity trajectory. J. Appl. Psychol. 107, 310–318 (2022).

Bunderson, J. S. & Sutcliffe, K. M. Management team learning orientation and business unit performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 552–560 (2003).

Leahey, E. From sole investigator to team scientist: trends in the practice and study of research collaboration. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 42, 81–100 (2016).

Castañer, X. & Oliveira, N. Collaboration, coordination, and Cooperation among organizations: Establishing the distinctive meanings of these terms through a systematic literature review. J. Manag. 46, 965–1001 (2020).

Lee, Y. N., Walsh, J. P. & Wang, J. Creativity in scientific teams: unpacking novelty and impact. Res. Policy. 44, 684–697 (2015).

Stephens, B. & Cummings, J. N. Knowledge creation through collaboration: the role of shared institutional affiliations and physical proximity. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 72, 1337–1353 (2021).

Wagner, C. S., Whetsell, T. A. & Mukherjee, S. International research collaboration: novelty, conventionality, and atypicality in knowledge recombination. Res. Policy. 48, 1260–1270 (2019).

Downes, P. E., Gonzalez-Mulé, E., Seong, J. Y. & Park, W. W. To collaborate or not? The moderating effects of team conflict on performance-prove goal orientation, collaboration, and team performance. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 94, 568–590 (2021).

Lim, J. Y. & Lim, K. Y. Co-regulation in collaborative learning: grounded in achievement goal theory. Int. J. Educ. Res. 103, 101621 (2020).

Li, H., Yang, X. & Cai, X. Academic spin-off activities and research performance: the mediating role of research collaboration. J. Technol. Transf. 47, 1037–1069 (2022).

Lyu, D., Gong, K., Ruan, X., Cheng, Y. & Li, J. Does research collaboration influence the disruption of articles? Evidence from neurosciences. Scientometrics 126, 287–303 (2021).

Hall, K. L. et al. The science of team science: A review of the empirical evidence and research gaps on collaboration in science. Am. Psychol. 73, 532–548 (2018).

Ryazanova, O. & McNamara, P. Socialization and proactive behavior: multilevel exploration of research productivity drivers in U.S. Business schools. AMLE 15, 525–548 (2016).

Eccles, J. S. & Wigfield, A. From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and Sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 61, 101859 (2020).

Hoever, I. J., Betancourt, N. E., Chen, G. & Zhou, J. How others light the creative spark: low power accentuates the benefits of diversity for individual inspiration and creativity. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 176, 104248 (2023).

Donovan, J. J., Hafsteinsson, L. G. & Lorenzet, S. J. The interactive effects of achievement goals and task complexity on enjoyment, mental focus, and effort. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 48, 136–149 (2018).

Kuhn, T. S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (The University of Chicago Press, 1962).

Xu, J. A profile analysis of online assignment motivation: combining achievement goal and expectancy-value perspectives. Comput. Educ. 177, 104367 (2022).

Dweck, C. S. & Leggett, E. L. A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychol. Rev. 95, 256–273 (1988).

Melin, G. Pragmatism and self-organization: research collaboration on the individual level. Res. Policy. 29, 31–40 (2000).

Brett, J. & Vandewalle, D. Goal orientation and goal content as predictors of performance in a training program. J. Appl. Psychol. 84, 863–873 (1999).

Hirst, G., Van Knippenberg, D. & Zhou, J. A cross-level perspective on employee creativity: goal orientation, team learning behavior, and individual creativity. Acad. Manag J. 52, 280–293 (2009).

Jamali, H. R., Nicholas, D. & Herman, E. Scholarly reputation in the digital age and the role of emerging platforms and mechanisms. Res. Eval. 25, 37–49 (2016).

Civera, A., Lehmann, E. E., Paleari, S. & Stockinger, S. A. E. Higher education policy: why hope for quality when rewarding quantity? Res. Policy. 49, 104083 (2020).

Cabrera, A. & Cabrera, E. F. Knowledge-sharing dilemmas. Organ. Stud. 23, 687–710 (2002).

Rhee, Y. W. & Choi, J. N. Knowledge management behavior and individual creativity: goal orientations as antecedents and in-group social status as moderating contingency. J. Organ. Behav. 38, 813–832 (2017).

Bikard, M., Murray, F. & Gans, J. S. Exploring trade-offs in the organization of scientific work: collaboration and scientific reward. Manag Sci. 61, 1473–1495 (2015).

Ma, Y. & Uzzi, B. Scientific prize network predicts who pushes the boundaries of science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 115, 12608–12615 (2018).

So, H. J. & Brush, T. A. Student perceptions of collaborative learning, social presence and satisfaction in a blended learning environment: relationships and critical factors. Comp. Educ. 51, 318–336 (2008).

Zhang, C., Wang, F., Huang, Y. & Chang, L. Interdisciplinarity of information science: an evolutionary perspective of theory application. J. Doc. 80, 392–426 (2023).

Haeussler, C. & Sauermann, H. Division of labor in collaborative knowledge production: the role of team size and interdisciplinarity. Res. Policy. 49, 103987 (2020).

Boudreau, K. J., Guinan, E. C., Lakhani, K. R. & Riedl, C. Looking across and looking beyond the knowledge frontier: intellectual distance, novelty, and resource allocation in science. Manag Sci. 62, 2765–2783 (2016).

Hallonsten, O. Stop evaluating science: A historical-sociological argument. Social Sci. Inform. 60, 7–26 (2021).

Grant, H. & Dweck, C. S. Clarifying achievement goals and their impact. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 85, 541–553 (2003).

Choi, W., Madjar, N. & Yun, S. Suggesting creative solutions or just complaining: perceived organizational support, exchange ideology, and learning goal orientation as determining factors. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat Arts. 12, 68–78 (2018).

Liu, D., Wang, S. & Wayne, S. J. Is being a good learner enough?? An examination of the interplay between learning goal orientation and impression management tactics on creativity. Pers. Psychol. 68, 109–142 (2015).

Deichmann, D. & van den Ende, J. Rising from failure and learning from success: the role of past experience in radical initiative taking. Organ. Sci. 25, 670–790 (2014).

Clercq, D. D., Rahman, Z. M. & Belausteguigoitia, I. Task conflict and employee creativity: the critical roles of learning orientation and goal congruence. Hum. Resour. Manag. 56, 93–109 (2017).

Urdan, T. & Kaplan, A. The origins, evolution, and future directions of achievement goal theory. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 61, 101862 (2020).

Ames, C. & Archer, J. Achievement goals in the classroom: students’ learning strategies and motivation processes. J. Educ. Psychol. 80, 260–267 (1988).

Elliot, A. J., McGregor, H. A. & Gable, S. Achievement goals, study strategies, and exam performance: A mediational analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 91, 549–563 (1999).

Wigfield, A. & Eccles, J. S. Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 25, 68–81 (2000).

Putwain, D. W., Nicholson, L. J., Pekrun, R., Becker, S. & Symes, W. Expectancy of success, attainment value, engagement, and achievement: A moderated mediation analysis. Learn. Instr. 60, 117–125 (2019).

Lee, H. H. & Yang, T. T. Employee goal orientation, work unit goal orientation and employee creativity. Creat Innov. Manag. 24, 659–674 (2015).

Janssen, O. & Van Yperen, N. W. Employees’ goal orientations, the quality of Leader-Member exchange, and the outcomes of job performance and job satisfaction. Acad. Manag J. 47, 368–384 (2004).

Duda, J. L. & Nicholls, J. G. Dimensions of achievement motivation in schoolwork and sport. J. Educ. Psychol. 84, 290–299 (1992).

Özveren, E. & Gürpinar, E. More a commons than a fictitious commodity: Tacit knowledge, sharing, and Cooperation in knowledge governance. J. Knowl. Econ. 15, 3824–3843 (2024).

Ugonna, D. C. U., Ochieng, P. E. G. & Zuofa, D. T. Augmenting the delivery of public research and development projects in developing countries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 169, 120830 (2021).

Brislin, R. W. Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural research. J. Cross-Cultural Psychol. 1, 185–216 (1970).

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y. & Podsakoff, N. P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 88, 879–903 (2003).

Morgeson, F. P., Mitchell, T. R. & Liu, D. Event system theory: an event-oriented approach to the organizational sciences. Acad. Manag Rev. 40, 515–537 (2015).

Liu, D., Chen, Y. & Li, N. Tackling the negative impact of COVID-19 on work engagement and taking charge: A multi-study investigation of frontline health workers. J. Appl. Psychol. 106, 185–198 (2021).

Bozeman, B., Fay, D. & Slade, C. P. Research collaboration in universities and academic entrepreneurship: the-state-of-the-art. J. Technol. Transf. 38, 1–67 (2013).

Lungeanu, A., Huang, Y. & Contractor, N. S. Understanding the assembly of interdisciplinary teams and its impact on performance. J. Informetrics. 8, 59–70 (2014).

Muriithi, P., Horner, D., Pemberton, L. & Wao, H. Factors influencing research collaborations in Kenyan universities. Res. Policy. 47, 88–97 (2018).

Yu, N., Dong, Y. & de Jong, M. A helping hand from the government? How public research funding affects academic output in less-prestigious universities in China. Res. Policy. 51, 104591 (2022).

Yang, Z., Chen, Z., Shao, S. & Yang, L. Unintended consequences of additional support on the publications of universities: evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 175, 121350 (2022).

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market Res. 18, 39–50 (1981).

Edwards, J. R. & Lambert, L. S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods. 12, 1–22 (2007).

Kim, J. B., Moon, K. S. & Park, S. When is a performance-approach goal unhelpful? Performance goal structure, task difficulty as moderators. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 22, 261–272 (2021).

van der Wouden, F. A history of collaboration in US invention: changing patterns of co-invention, complexity and geography. Ind. Corp. Change. 29, 599–619 (2020).

Cohen-Meitar, R., Carmeli, A. & Waldman, D. A. Linking meaningfulness in the workplace to employee creativity: the intervening role of organizational identification and positive psychological experiences. Creat Res. J. 21, 361–375 (2009).

De Dreu, C. K. W. Cooperative outcome interdependence, task reflexivity, and team effectiveness: a motivated information processing perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 92, 628–638 (2007).

Zhang, J., Wang, Y. & Zhang, M. Y. Team leaders matter in knowledge sharing: A cross-level analysis of the interplay between leaders’ and members’ goal orientations in the Chinese context. Manag Organ. Rev. 14, 715–745 (2018).

Eatough, E. M., Chang, C. H., Miloslavic, S. A. & Johnson, R. E. Relationships of role stressors with organizational citizenship behavior: A meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 96, 619–632 (2011).

Boswell, W. R., Olson-Buchanan, J. B. & LePine, M. A. Relations between stress and work outcomes: the role of felt challenge, job control, and psychological strain. J. Vocat. Behav. 64, 165–181 (2004).

Wang, Y., Huang, Q., Davison, R. M. & Yang, F. Role stressors, job satisfaction, and employee creativity: the cross-level moderating role of social media use within teams. Inf. Manag. 58, 103317 (2021).

Liu, M. & Hu, X. Will collaborators make scientists move? A generalized propensity score analysis. J. Informetrics. 15, 101113 (2021).

Jones, B. F. The burden of knowledge and the death of the renaissance man: is innovation getting harder? Rev. Econ. Stud. 76, 283–317 (2009).

Picciotto, G. & Fabio, R. A. Does stress induction affect cognitive performance or avoidance of cognitive effort? Stress Health. 40, e3280 (2024).

Conley, A. M. Patterns of motivation beliefs: combining achievement goal and expectancy-value perspectives. J. Educ. Psychol. 104, 32–47 (2012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C. and H.Z. conceptualized the study. Data curation and methodology were conducted by L.C. and C.Z. The formal analysis was carried out by L.C., who also wrote the original draft. Both L.C. and C.Z. were involved in reviewing and editing the manuscript. Supervision was provided by H.Z. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, L., Zhang, C. & Zhang, H. The role of goal orientation, collaboration, and stress in shaping scientific creativity. Sci Rep 16, 3064 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08803-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08803-8