Abstract

This study experimentally investigates the structural behavior of steel–concrete composite slabs under monotonic loading, with a focus on evaluating the influence of fiber content, fiber types, layer arrangement, and screw density on their performance. Twelve composite slabs, consisting of two layers of lightweight aggregate concrete (LWAC) and fiber-reinforced concrete (FRC) cast on steel decking, were fabricated and subjected to four-point bending tests. Experimental variables included fiber volumes (0.1%, 0.3%, 0.5%), fiber types (steel, polypropylene, or hybrid steel‒polypropylene), shear connector types (screws, end shear studs), screw spacings (200 mm, 300 mm), and layer arrangement. The results showed that increasing the fiber content significantly enhanced load resistance, reduced end slip, and improved strain capacity. Specifically, slabs with 0.5% fiber content achieved a 155% higher load capacity compared to those with 0.1%. Placing fiber-reinforced concrete (FRC) in the bottom layer and lightweight aggregate concrete (LWAC) on top provided better composite action, optimizing the performance of all components. Screw connectors greatly improved shear bond resistance and flexural strength, with slabs using 200 mm screw spacing showing 2.6 times higher strength than those without screws. Compared to traditional steel–concrete composite slabs, screw reinforcement increased flexural strength by up to 164%. The combination of FRC and screws led to favorable failure modes, such as distributed flexural and shear cracking with slip, which effectively utilized the full material capacity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Composite slabs combining structural concrete with innovative materials are widely used in modern construction, offering advantages like reduced self-weight and streamlined construction processes1,2,3. Renowned for their economic and structural efficiency, these composite decking slabs have become a preferred choice in various projects. The profiled steel sheeting functions as both permanent formwork and tensile reinforcement, providing critical support throughout the slab’s service life. These systems address critical failure modes at the concrete‒steel interface, where shear bond resistance is crucial to maintaining structural integrity. Failure at this interface often dominates the overall system’s performance, with mechanical failure and excessive end slip lengths being the primary failure mechanisms.

Shear bond failure—commonly seen as end slip or delamination—remains a major concern in composite slabs. Several studies4,5,6 investigated various configurations of steel profiled sheeting to enhance the shear resistance between the concrete and steel decking. Other studies7,8 addressed this issue by developing mechanical interlocks to improve interfacial friction between the two materials. Screw-type shear connectors, in particular, enhance mechanical interlocking, suppress crack propagation, and significantly improve ductility and shear bond resistance9,10,11,12,13,14.

According to reference7the optimal placement of screws significantly enhances shear bond resistance, reduces end slip, and improves ductility in composite slabs. This approach is more economical and practical compared to the heavier and more complex system proposed in15which, while effective, is less feasible for widespread application. The study emphasizes the importance of carefully controlling screw density and placement to maximize load transfer and minimize crack propagation.

The integration of lightweight aggregate concrete (LWAC) and fiber-reinforced concrete (FRC) has enhanced composite systems by reducing weight while improving load-bearing capacity and durability16,17. Advances in laminated designs, which combine LWAC and FRC layers, have demonstrated superior mechanical performance and load distribution6,13,18. In addition to innovations in connector technology, improvements in concrete materials have significantly boosted the performance of composite slabs.

LWAC is valued for its lightness but is inherently brittle and prone to cracking. To address these limitations, lightweight aggregate concrete reinforced with steel and polypropylene fibers has been developed, offering improved tensile strength, ductility, and resistance to fire and cracking19,20,35. Youssf et al.36 studied the cyclic performance of steel–concrete–steel sandwich beams with rubber concrete and lightweight expanded clay aggregate as the lightweight core to highlight the role of shear connectors in ductility and bond performance. Tahwia et al.37 further identified that chopped basalt fiber will ameliorate compressive strength, impact resistance, and microstructural arrangement of high-performance concrete. Building on this, researchers have introduced laminated composite slabs featuring two layers: an upper LWAC layer and an underlying FRC layer. Their findings demonstrated that this laminated configuration improves structural performance and load distribution compared to monolithic slabs.

A comparative study of existing design methods, including the m-k method and partial shear connection theory, revealed that these approaches fail to accurately predict the load capacity of laminated slabs. However, the proposed modifications, which account for the unique mechanical properties of the two layers, yielded significantly more accurate predictions. These results underscore the need for tailored design strategies for composite systems incorporating advanced materials like FRC.

The addition of fibers to concrete matrices has significantly enhanced crack resistance and tensile strength 21,22,23. Polypropylene fibers improve ductility and effectively control plastic shrinkage cracks but offer limited load-bearing capacity compared to steel fibers24,25. Steel fibers, on the other hand, excel in enhancing flexural and shear resistance, making them suitable for high-stress applications26.

Hybrid fiber systems combine the strengths of polypropylene and steel fibers, achieving synergistic improvements in ductility, crack distribution, and post-crack performance, particularly under high-loading conditions27,28,29,30,31,32,33. The combined effect of these fibers enhances crack control and flexural strength, suggesting that hybrid fiber-reinforced laminated slabs can outperform conventional systems.

LWAC is increasingly used due to its lightness and cost-effectiveness. However, its inherent brittleness and susceptibility to cracking have limited its structural applications, prompting the development of FRC, which incorporates steel and polypropylene fibers to enhance tensile strength and crack resistance33,34. Additionally, two-layer pouring techniques, where a reinforced bottom layer supports a standard LWAC top layer, have shown potential for improving load transfer and shear resistance20,29.

While the structural performance of composite slabs using laminated pouring processes has been studied, prior research has primarily focused on either material innovations or connector enhancements. The combined effects of advanced screw connectors and hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete layers on shear bond strength, end slip reduction, and crack propagation control remain underexplored. Therefore, this study addresses these gaps by investigating composite slabs featuring various laminated LWAC and FRC layer configurations, as well as shear connector types and densities. This study is a new comprehensive experimental work, evaluating mixed FRC and LWAC in 12 steel‒concrete composite slabs under monotonic loading tests, with key variables including fiber content (0.1%, 0.3%, 0.5%), fiber type (steel, polypropylene, hybrid steel‒polypropylene), and shear connector spacing (200 mm, 300 mm). The key expected finding of this study is to develop an efficient lightweight composite slab system.

Experimental program

In this study, twelve steel‒concrete composite slabs are fabricated. The slab parameters involving the combined fiber-reinforced concrete (FRC) and lightweight aggregate concrete (LWAC), the fiber types and amount, and the configurations and details of shear connectors are analyzed.

Design of specimen and material properties

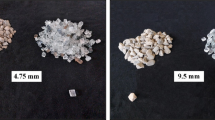

The overall geometries of all the slab specimens are with width (b) × length (L) × height (h) = 720 × 3800 × 150 mm3. The profiled steel sheet used in this study is illustrated in Fig. 1 a and b, with its geometric and material properties summarized in Table 1. Figure 1c and d illustrate the steel decking with screws and shear studs at each end, respectively. Figure 1e demonstrates the concrete layers arranged in the composite slabs. The steel decking had a thickness of 0.95 mm, a yield strength of 395 MPa, and an elastic modulus of 200 GPa. Lightweight aggregate concrete (LWAC) was prepared using Karemzit aggregates with grain sizes ranging from 10 mm to 20 mm, shown in Fig. 2a. Polypropylene fibers and steel fibers were added to produce fiber-reinforced concrete (FRC) (Fig. 2b and c) with mixed proportions in a 3:7 ratio. Table 2 shows the concrete mix design. The fiber content in the concrete mix was categorized into three levels 0.1%, 0.3%, and 0.5%. Figure 2d illustrates the screw dimension.

Designations for each slab are identified as follows: RC represents reinforced concrete with steel bars with a diameter of 8 mm, a percentage of steel reinforcement of 0.175%, FH refers to hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete, FHS denotes fiber-reinforced concrete with shear keys, FPS indicates polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete only, FSS refers to fiber steel concrete with screws, FHST refers to hybrid fiber-reinforced concrete with end shear studs. Configurations with “I”, “II”, and “III” represent fiber content levels of 0.1%, 0.3%, and 0.5%, respectively, while “O” indicates reversed layers of concrete.

The slabs included 250 mm of development length from each support. Shear span lengths were kept constant at Ls = L’/4, in which L’ is the length of the slabs between two supports. Screw spacings were generally 200 mm, except for slabs 11 and 12, which featured 300 mm spacings. Table 3 summarizes all the slab configurations. Figure 3a, b present the elevation view of the slab details. The testing setup included a 500 kN capacity load cell, a 50 mm capacity displacement transducer, and a data logger for monitoring test data. Strain gauges were used to measure the strain in the concrete and profiled steel sheeting, as illustrated in Fig. 3b.

To cast the composite slabs, the FRC was first poured to a specified thickness, followed by the immediate pouring of LWAC before the initial setting of the lower layer for at least 30 min, as shown in Fig. 1e. Shear connectors, including screws and studs, were installed according to the specific design configurations. The concrete layer thickness for each layer was followed by the experimental studies of Li et al.20with the most effectiveness of the first layer about 90–100 mm from the bottom of the steel decking. The slabs underwent 30 days of curing, employing a wet curing method.

Test setup

The experimental setup with four-point bending tests consisted of simply supported slabs with a pin and roller at each end. A 500 kN electrohydraulic system applied a concentrated load at L’/4 using a loading control method at 0.2 kN/second. The test setup is illustrated in Fig. 3a and b. Displacements at the middle and applied load points were measured using the linear variable displacement transducers (LVDTs). Strains in the steel decking and concrete at the mid-span were recorded using the strain gauges. The slipping between concrete and steel decking was determined by monitoring longitudinal displacements in the concrete and the steel sheet.

Results and analysis

Load versus deflection

The load‒deflection curves in Fig. 4a‒d depict the behavior of composite slabs under monotonic loading. Table 4 presents the peak loads and corresponding deflections observed during the experiments for all tested specimens. Initially, all experimental curves display a linear phase, reflecting elastic behavior until the onset of cracking. Following crack initiation, the responses deviate, signaling a redistribution of internal stress and a reduced stiffness within the composite slabs. These variations are attributed to the influences of the type and content of fibers as well as the screw spacing, which are analyzed in the following sections.

Effect of fiber content

To investigate the fiber content, Fig. 4a compares the performance of five specimens, 1-FH-I (0.1% mixed steel‒polypropylene fibers), 2-FH-II (0.3% mixed steel‒polypropylene fibers), 3-FH-III (0.5% mixed steel‒polypropylene fibers), 9-FPS-II (0.3% polypropylene fibers only), and 10-RC (concrete with lightweight aggregate and conventional steel reinforcement). Note that those slabs were without any screw shear connectors. Regarding the slabs containing fibers, slab 9-FPS-II achieves the highest load capacity (44.3 kN), followed by slab 3-FH-III (41.9 kN). While both slabs exhibit similar stiffness, slab 3-FH-III shows a more significant displacement at peak load (11 mm) compared to 10.5 mm for slab 9-FPS-II. Specimen 2-FH-II (28 kN) outperforms slab 1-FH-I (27 kN) in terms of load capacity but displays lower deflection (6.6 mm versus 7.3 mm). Specimen 10-RC achieves a load capacity of 43.7 kN with a deflection of 10.9 mm, slightly lower than the capacity of 9-FPS-II but comparable in overall performance. However, compared to slab 3-FH-III, specimen 10-RC exhibits reduced ductility, emphasizing that higher fiber content in slabs significantly improves stiffness, load-carrying capacity, and overall ductility. The primary reason for the aforementioned observations is that a higher fiber content creates stronger and more uniformly distributed bridge connections. This improvement enhances the continuity and integrity of the concrete matrix, thereby increasing its resistance to applied forces.

Effect of layer arrangement

Figure 4b compares the performance of four specimens: 7-FHST-II (0.3% mixed steel‒polypropylene fibers with end shear studs), 8-FHST-O-II (0.3% mixed steel‒polypropylene fibers with end shear studs but reversed concrete layers), 4-FHS-II (0.3% mixed steel fibers with 200 mm screw spacing), and 5-FHS-O-II (0.3% mixed steel fibers with 200 mm screw spacing but reversed concrete layers). The comparison focuses on analyzing the impact of the arrangement of the two concrete layers. As a result, slab 4-FHS-II has the highest load capacity (71.8 kN) and a large deflection (24.8 mm) because the fiber-reinforced concrete was laid at the slab bottom, contributing to the tension capacity alongside the steel sheet. In comparison to 4-FHS-II, although utilizing the lightweight aggregate concrete in the slab bottom, specimen 5-FHS-O-II achieves a slightly smaller peak load (66.6 kN) and lower displacement (23.9 mm). The possible reason is that the use of distributed anchored screws in both slabs provides effective tension resistance, resulting in a similar failure mechanism. Conversely, slab 8-FHST-O-II with lightweight aggregate concrete for the bottom layer displays higher load capacity than slab 7-FHST-II (50.7 kN compared to 42.3 kN). This is attributed to the weak welding of the end shear studs in these slabs, leading to a different failure mechanism when the end shear studs interact with the soffit layer. Indeed, as observed during the experimental process, the end shear studs in slab 7-FHST-II sustained premature damage, leading to the early failure of the slab.

Effect of fiber types

To examine the effect of fiber types, Fig. 4c compares the load‒deflection responses of four slabs, 4-FHS-II (0.3% mixed polypropylene‒steel fibers), 9-FPS-II (0.3% polypropylene fibers only), 6-FH-II (0.3% steel fibers only), and 10-RC (conventional steel reinforcement and lightweight aggregate concrete). The experimental results indicate that specimen 4-FHS-II, using combined two types of fibers, offered the highest load capacity at 71.8 kN, increasing by 64% approximately compared to the reference slab (10-RC). Then, slab 6-FH-II with individual steel fibers reaches the maximum load-carrying capacity of 63.6 kN. In contrast, specimen 9-FPS-II, with only polypropylene fibers, achieves a lower load capacity of 44.3 kN, which is close to the peak load obtained from specimen 10-RC. These results indicate that using steel fibers and mixed polypropylene and steel fibers is an effective solution in significantly improving the strength of the composite slabs. Furthermore, replacing conventional steel reinforcement in the composite slab with microfibers is also an effective solution.

Effect of screw density

The effect of screw density is presented in Fig. 4d by evaluating the performance of five slabs, 4-FHS-II (0.3% mixed fibers and 200 mm screw spacing), 6-FSS-II (0.3% steel fibers and 200 mm screw spacing), 11-FHS-II-300 (0.3% mixed fibers and 300 mm screw spacing), and 12-FSS-II-300 (0.3% steel fibers and 300 mm screw spacing). Clearly, the narrower the screw spacing, the higher the slab strength and stiffness. Indeed, the specimen 4-FHS-II (200 mm screw distance) achieves a maximum load of 71.8 kN with a deflection of 24.8 mm, outperforming the specimen 11-FHS-II-300 (300 mm screw distance) at 47.5 kN and 32.5 mm in load capacity of 51.2% and less deflection of 23.8%. Meanwhile, the 6-FSS-II (200 mm screw distance) achieves 63.6 kN with a deflection of 29.1 mm, outperforms the specimen 12-FSS-II-300 (300 mm screw spacing) at 52.9 kN and 38 mm in load capacity of 20.2% and less deflection than 23.4%. The possible reason for those observations is explained by the addition of screws furnishing the improved stress transfer between concrete and steel decking. This finding agrees well with that obtained in the literature for conventional and other steel‒concrete composite slabs7,8,13,14.

End slip between concrete and steel decking

The load‒end slip graphs in Fig. 5a and b are provided to investigate the interfacial interaction between concrete and steel decking considering the effects of the slab parameters. The end slip between concrete and steel decking is defined by the difference between longitudinal displacements measured in the concrete and the steel sheet.

Effect of fiber content

Figure 5a compares the load‒end slip curves of five specimens: 1-FH-I (0.1% mixed steel‒polypropylene fibers), 2-FH-II (0.3% mixed steel‒polypropylene fibers), 3-FH-III (0.5% mixed steel‒polypropylene fibers), 9-FPS-II (0.3% polypropylene fibers), and 10-RC (conventional composite slab with lightweight aggregate concrete). Initially, the end slip responses of those specimens are similar due to their elastic phases. The end slips of all specimens increased as the load increased, and the slip became significant when the cracks formed, leading to the loss of local bonding between steel decking and concrete. The end slip recorded in slab 9-FPS-II (with polypropylene fibers only) is the smallest. This result might be caused by the distribution and orientation of fibers in the composite slab. Meanwhile, the remaining specimens in Fig. 5a provided similar slip responses in the pre-peak regime but larger end slip than slab 9-FPS-II. Further, as observed from the results of specimens with hybrid fibers, the higher the fiber content, the larger the slip at peak load. Indeed, the end slips at maximum loads by 2.09 mm, 0.69 mm, and 0.62 mm for slabs 3-FH-III, 2-FH-II, and 1-FH-I, respectively. This is possibly explained by the fact that the addition of fibers led to the improvement of interlocking friction between the concrete matrix and steel sheet. The conventional slab 10-RC provided smaller end slip than that in the composite slabs with FRC. However, the ductility of the composite slabs with FRC based on end slip endurance is more excellent than that of the conventional composite slab.

Effect of concrete layer arrangement and fiber types

Figure 5b compares the load‒end slip curves of four specimens: 7-FHST-II (0.3% mixed steel‒polypropylene fibers with end shear studs), 8-FHST-O-II (0.3% mixed steel‒polypropylene fibers with end shear studs and reversed concrete layers—FRC layer is above LWAC layer), 4-FHS-II (0.3% mixed steel fibers with 200 mm screw spacing), 5-FHS-O-II (0.3% mixed steel fibers with screws and reversed concrete layers—FRC layer is above LWAC layer). It is transparent that the slabs with the FRC layer located in the bottom provided smaller end slip responses, particularly at the low load level stage. This is because the bond strength between FRC and steel decking is higher than that between LWAC and steel decking. At high load levels, the end slips of the specimens are dependent on other parameters, for example, cracking configurations and anchored studs. Slab 4-FHS-II with FRC in the bottom layer and with screws spaced at 200 mm performs a superior end slip resistance and ductility. This result is consistent with the slab deflection behavior analyzed in the above section. Therefore, the configuration details of specimen 4-FHS-II can be considered a good design for the composite slab in the practical application.

Figure 5b examines the results obtained from the specimens 4-FHS-II (0.3% mixed steel fibers) and 9-FPS-II (0.3% polypropylene fibers) to evaluate the effect of fiber types on the composite slabs’ end slip responses. The end slip development of those specimens is similar. However, the slab with hybrid fibers in FRC offered high flexural strength and slip ductility (i.e., the increase in slip did not result in a sudden drop in load).

Strain in concrete

The relations between load and concrete strain at the top fiber of the slabs are shown in Fig. 6a‒d. The strain values at the maximum loads for the tested slabs are depicted in Table 4. Overall, the concrete in the compression zone of all specimens did not fail as the maximum strain is less than 2500 (µm/m) as observed during the bending test.

Effect of fiber content

The effect of fiber content is assessed through the strain responses recorded from five specimens: 1-FH-I (0.1% mixed steel‒polypropylene fibers), 2-FH-II (0.3% mixed steel‒polypropylene fibers), 3-FH-III (0.5% mixed steel‒polypropylene fibers), 9-FPS-II (0.3% polypropylene fibers), and 10-RC (conventional steel reinforcement and LWAC), as shown in Fig. 6a. Note that the slabs 1-FH-I, 2-FH-II, 3-FH-III, and 9-FPS-II were configured with two layers of concrete: the bottom layer was FRC and the top layer was LWAC. Among them, slab 3-FH-III achieves the highest strain value (460 μm/m) at the peak load capacity due to its higher fiber amount (0.5%), triggering the compression strain in LWAC to equilibrate with the high tension strain provided by the steel decking and FRC. Slab 9-FPS-II, with 0.3% polypropylene fibers, shows lower strain (339 μm/m) because polypropylene fibers provide limited tensile contribution compared to steel fibers. At the same load level, specimens 2-FH-II and 1-FH-I exhibit similar strain values to those monitored in slab 3-FH-III; however, they provide smaller strains corresponding to their peak loads due to their lower fiber content. In contrast, reference slab 10-RC achieves a larger 604 μm/m strain than others at its maximum load.

Effect of concrete layer arrangement

The change of positions of FRC and LWAC in the composite slabs is investigated through Fig. 6b, which includes the load‒strain curves of 7-FHST-II (0.3% mixed fibers with end shear studs), 8-FHST-O-II (0.3% mixed fibers with end shear studs and reversed concrete layers), 4-FHS-II (0.3% steel fibers with 200 mm screw spacing), and 5-FHS-O-II (0.3% steel fibers with 200 mm screw spacing and reversed concrete layers). Generally, swapping the FRC and LWAC layers significantly affects the strain in the top fiber of the composite slabs. Specimen 8-FHST-O-II with end shear studs and FRC in the top layer provides more significant deformation at the extreme top fiber of the slab than that of specimen 7-FHST-II with end shear studs and LWAC in the top layer. In contrast, when using screws, the slab 4-FHS-II with LWAC in the top layer results in larger strain than that in the specimen 5-FHS-O-II with FRC in the upper layer. To activate the strain in the compression zone of the composite slab, the configuration of slab 4-FHS-II is a suitable designation.

Effect of fiber types

Figure 6c evaluates the strain development of compressive concrete in three slabs 4-FHS-II (0.3% mixed steel and polypropylene fibers), 6-FSS-II (0.3% steel fibers only), and 9-FPS-II (0.3% polypropylene fibers only). The difference in the fiber types in the FRC layer laid at the slab bottom leads to the difference in strain in the extreme top fiber of LWAC located at the upper part of the slab. Using mixed and steel fibers triggers the strain in the concrete compressive zone, enhancing the slab bending capacity. Slab 4-FHS-II achieves a maximum strain of 760 μm/m and a load capacity of 71.8 kN. Specimen 6-FSS-II achieves a maximum strain of 830 μm/m and a load capacity of 63.6 kN, which is substantially larger than that recorded in specimen 9-FPS-II (339 μm/m for maximum concrete compressive strain and load capacity 44.3 kN for load-carrying capacity).

Effect of screw density

The effect of screw density on the strain development in the concrete compressive zone of the composite slabs is presented in Fig. 6d. The following specimens are considered for this purpose: 4-FHS-II (0.3% mixed fibers with 200 mm screw spacing), 6-FSS-II (0.3% steel fibers with 200 mm screw spacing), 11-FHS-II-300 (0.3% mixed fibers with 300 mm screw spacing), and 12-FSS-II-300 (0.3% steel fibers with 300 mm screw spacing).

The narrower the screws, the smaller the strain in the compressive zone. Slabs 11-FHS-II-300 and 12-FSS-II-300 achieve the large strains by 1370 and 949 μm/m, respectively, due to their wider screw spacing, which reduces load transfer efficiency but enhances deformation capacity. Slabs 4-FHS-II and 6-FSS-II, both with 200 mm screw spacing, achieve significant load capacities (71.8 kN and 63.6 kN) but show lower maximum strains (760 μm/m and 830 μm/m), confirming that tighter screw spacing improves load resistance while controlling strain.

Strain in steel decking

The relations between load and steel decking strain at the bottom fiber of the slabs are shown in Fig. 7a‒d. The strain values recorded at the maximum loads for the tested slabs are depicted in Table 4. Overall, the steel strain values for all tested specimens remained below the yielding strain limit of the steel decking (εys = 1975 μm/m). Most of the specimens exhibit the distinct three phases in the strain development of the steel decking.

Effect of fiber content

Figure 7a compares the load‒steel strain behavior of four specimens, 1-FH-I, 2-FH-II, 3-FH-III, and 9-FPS-II, to examine the effect of fiber content. The different fiber contents affect the tensile capacity of the composite slabs along with the steel decking. Therefore, the strain in the steel decking differed among the specimens. Slab 3-FH-III achieves the highest steel strain (800 μm/m) due to its higher fiber content (0.5%), enhancing tensile resistance.

Effect of concrete layer arrangement

Figure 7b compares the load‒steel strain behavior of four specimens: 4-FHS-II, 5-FHS-O-II, 7-FHST-II, and 8-FHST-O-II. Slab 4-FHS-II achieves the maximum steel sheet strain by 1177.4 μm/m with the highest load capacity. When swapping the FRC and LWAC layers, specimen 5-FHS-O-II exhibits a lower maximum steel strain of 474 μm/m. However, using the end shear studs, slabs 7-FHST-II and 8-FHST-O-II record moderate steel strains by 915.1 μm/m and 961.3 μm/m, respectively. This means that the specimens with swapping of the FRC and LWAC layers provided the inconsistent result to the slabs with different shear connectors.

Effect of fiber types

To examine the strain in steel decking of the slab considering the design variable of fiber types, Fig. 7c evaluates the load‒steel strain responses of three slabs: 4-FHS-II (0.3% mixed fibers), 6-FSS-II (0.3% steel fibers only), and 9-FPS-II (0.3% polypropylene fibers only). Using steel fibers in slab 6-FSS-II is beneficial in activating the maximum steel sheet strain by 1377 μm/m. Slab 4-FHS-II, with 0.3% mixed fibers, shows a slightly lower strain in steel decking by 1177 μm/m but the highest load capacity by 71.8 kN. In contrast, slab 9-FPS-II with only polypropylene fibers records the lowest steel strain in the steel sheet by 681 μm/m and reduced load capacity by 44.3 kN.

Effect of screw density

The effect of screw density on the strain development in steel decking of the composite slabs is investigated through Fig. 7d, which compares the load‒steel strain curves of four slabs: 4-FHS-II (0.3% mixed fibers, 200 mm screw spacing), 6-FSS-II (0.3% steel fibers, 200 mm screw spacing), 11-FHS-II-300 (0.3% mixed fibers, 300 mm screw spacing), 12-FSS-II-300 (0.3% steel fibers, 300 mm screw spacing). It is clear that the larger the gap of the screws, the greater the strain in steel decking. Slab 11-FHS-II-300 achieves the highest steel decking strain (1370 μm/m) but a moderate load capacity (47.5 kN).

Specimen 12-FSS-II-300, using steel fibers, achieves a steel strain of 1014 μm/m and a load capacity of 52.9 kN, reflecting the combined benefits of steel fibers and 300 mm screw spacing. Slabs 4-FHS-II and 6-FSS-II, with narrower 200 mm screw spacing, exhibit superior load capacities (71.8 kN and 63.6 kN) but lower strains (1177 μm/m and 1377 μm/m).

Analysis of failure modes and observed crack patterns

The observed crack patterns in the tested slabs reveal several critical failure mechanisms, including flexural cracking, distributed flexural cracking, shear cracks, and slipping, as categorized in Table 4; Figs. 8a‒c, and 9. This demonstrates the various levels of material utilization and structural responses. Due to bending action, all specimens occurred flexural cracks in the loading region of the slabs, which are commonly featured by the flexural members. The failure mode with flexural cracking coupled with slipping of steel decking from concrete (FC-S), as presented in Fig. 8a, was observed for slabs 1-FH-I, 2-FH-II, and 11-FHS-II-300, which occurs due to insufficient tensile strength. Cracks are localized in the tension zone beneath the load points, propagating vertically through the slab thickness. Meanwhile, the slip phenomenon observed in the slabs after testing is depicted in Fig. 9. Conversely, the distributed flexural cracking with slipping (DFC-S), observed in Fig. 8c, occurs in the slabs 3-FH-III, 9-FPS-II, 10-RC, and 12-FSS-II-300.

The failure mode of distributed flexural cracking combined with shear cracks and decking slipping (DFC-SC-S), shown in Fig. 8b, was found in the slabs 4-FHS-II, 5-FHS-O-II, 6-FSS-II, and 8-FHST-O-II. This is attributed to the contribution of the micro-fibers forming the distributed flexural cracks. Additionally, the installation of the screws triggered the high flexural capacity, consequently activating the significant shear mechanism to appear the inclined cracks. Overall, the crack observations highlight the transition from localized flexural cracks in under-reinforced slabs to distributed flexural and shear cracks in slabs with enhanced reinforcement and shear connectors.

Notably, slabs like 6-FSS-II achieve optimal performance by fully utilizing tensile, shear, and ductility capacities, emphasizing the importance of reinforcement strategies, fiber types, and shear connector spacing in improving load resistance and deformation performance. The conventional slab 10-RC exhibits a failure mode characterized by distributed flexural cracking with slight slipping (DFC-S). Cracks initiate early at the tension face due to the lower tensile strength of lightweight aggregate concrete. As the load increases, cracks propagate rapidly and localize, resulting in wider cracks than fiber-reinforced slabs. The absence of crack-bridging fibers accelerates crack growth, leading to brittle failure with minimal post-peak ductility.

Conclusions

In this study, the structural performance of the steel‒concrete composite slabs subjected to monotonic loading was investigated. The effects of fiber content, fiber types, concrete layer arrangement, and screw density on load capacity, deflection, strain behavior, and failure mechanisms were explored. The main conclusions of the present study are:

-

Increasing fiber content and adding screw stiffeners significantly improved load resistance, strain capacity, and stiffness. Indeed, a 155% increase in load capacity was observed at 0.5% fiber content compared to 0.1% in the tests. The slabs with FRC containing individual steel fibers and mixed steel‒polypropylene fibers outperformed those containing single polypropylene fibers and those with LWAC in flexural strength. Furthermore, the arrangement of FRC for the bottom layer exhibited the great load-carrying capacity of the composite slabs compared to the insertion of LWAC in the lower part. Inserting screw connectors with spacing of 200 mm in the slab significantly improved shear bond resistance and flexural strength by 2.6 times compared to slabs without screws. The use of the anchored screws was in better slip resistance than the use of the end shear studs for the shear connectors.

-

The concrete in the compression region of all slabs did not reach its crushing state (i.e., the maximum strain in concrete was smaller than 2500 µm/m), while the steel decking did not yield during the loading process. Three failure modes, including flexural cracking-slipping (FC-S), distributed flexural cracking-slipping (DFC-S), and distributed flexural cracking-shear cracking-slipping (DFC-SC-S), were identified in the tested slabs. The failure mode by DFC-SC-S occurred in the specimens with FRC and inserting narrow shear connectors by screws, which is deemed an effective failure mechanism of the composite slabs.

-

Future studies are recommended to examine the long-term behavior of the composite slabs under cyclic loading and fatigue conditions. Furthermore, exploring the advanced fiber types (i.e., hybrid fibers with volume differences) and optimized shear connector configurations is needed to provide a better understanding of enhancing crack control and structural efficiency. Furthermore, numerical and analytical studies on the composite slabs under various design variables are necessary to verify the experimental results in the present study, as well as to serve the practitioners in the design practice.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chen, X. & Ma, Q. Experimental study on the flexural performance of concrete Hollow composite slabs with tightly connected panel sides. Sci. Rep. 14, 20784. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71880-8 (2024).

Huang, P. et al. Experimental study on the bearing capacity of PZ shape composite dowel shear connectors with elliptical holes. Sci. Rep. 12, 2457. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-06387-1 (2022).

Van Cao, V., Vo, H. B., Dinh, L. H. & Van Doan, D. Monotonic and Cyclic behaviour of deficient reinforced concrete slabs retrofitted with externally bonded carbon fibre reinforced polymer. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. https://doi.org/10.1177/07316844231211675 (2023).

Vinod Kumar, M. et al. Comparative analysis of a novel lightweight composite-void steel deck slab and conventional solid slab: force carrying capacity, deflection, failure patterns, ductility and stiffness. J. Ind. Text. 54 https://doi.org/10.1177/15280837241301434 (2024).

Abu Altemen, A. A. G., Medhlom, M. K. & Özakça, M. Structural behavior of Full-Scale novel hybrid layered concrete slabs reinforced with CFRP and steel grids under impact load. Buildings 14(9), 2625. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14092625 (2024).

Lim, S. S., Wong, J. Y. & Yip, C. C. Pang. Flexural strength test on new profiled composite slab system. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 15 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00638 (2021).

Shirgaonkar, A. A., Patil, Y. D. & Patil, H. S. Influence of stiffeners and pattern of shear screws on behaviour of cold formed profiled deck composite floor. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 15 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cscm.2021.e00572 (2021).

Yang, D., Li, G., Au, F. T. K., Zhang, J. & Yuan, Y. Shear connector performance analysis for composite Bridge deck with corrugated steel sheeting. Adv. Struct. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1177/13694332241302699 (2024).

Saadoon, A. M., Mashrei, M. A., Al, K. A. & Oumari Jul. Punching shear strength of recycled aggregate-steel fibrous concrete slabs with and without strengthening. Adv. Struct. Eng. 25(10), 2175–2190 https://doi.org/10.1177/13694332221090288 (2022).

Porter, M. L., Greimann, L. F. & Portera, M. L. Steel Deck Slabs Shear-bond Strength of Studded Steel Deck Slabs. 7th International Specialty Conference on Cold-Formed Steel Structures, 1984. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/isccss/7iccfss/7iccfss-session6/1

Yuqing, H., Qi, J. & Wang, J. Experimental and numerical study on static behavior of grouped large-headed studs embedded in UHPC practical design theory for discontinuity regions (D-regions) in structural concrete View project. Steel Composite Struct. 36(1), 0–000 https://doi.org/10.12989/scs.2020.36.1.000 (2020).

Gao, Y. et al. Shear-slip behaviour of prefabricated composite shear stud connectors in composite bridges. Eng. Struct. 240 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2021.112148 (2021).

Shan, Y. et al. Flexural behavior of different types of steel-concrete composite decks with perfobond rib or head stud shear connectors. Adv. Struct. Eng. 26(7), 1187–1208. https://doi.org/10.1177/13694332231153954 (2023).

Vohra, H. S. & Dhankot, M. Shear connectors and composite deck slab experimental study—state of the art review. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. (IJSER) 3(3). Retrieved from http://www.ijser.in (2015).

Lakshmikandhan, K. N., Sivakumar, P., Ravichandran, R. & Jayachandran, S. A. Investigations on efficiently interfaced steel concrete composite deck slabs. J. Struct. 2013, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/628759 (2013).

Elsanadedy, H., Al Kallas, A., Abbas, H., Almusallam, T. & Al-Salloum, Y. Capacity reinstatement of reinforced concrete one-way ribbed slabs with rib-cutting shear zone openings: hybrid fiber reinforced polymer/steel technique. Adv. Struct. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1177/13694332241276060 (2024).

Garnevičius, M. & Gribniak, V. Developing a hybrid FRP-concrete composite beam. Sci. Rep. 12, Article 20666. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-20666-x (2022).

Li, Y., Chen, J., Shi, S., Hu, L. & Xu, X. Study of the design and flexural performance of an innovative fiber reinforced polymer/steel-concrete composite beam. Adv. Struct. Eng. 26 (1), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/13694332221119880 (2023).

Martínez-Martínez, J. E., Álvarez-Rabanal, F. P., Alonso-Martínez, M. & del Coz-Díaz, J. J. Nonlinear thermo-structural analysis of lightweight concrete and steel decking composite slabs under fire conditions: numerical and experimental comparison. Appl. Sci. 12(18), Article 9306. https://doi.org/10.3390/app12189306 (2022)..

Li, X., Zheng, X., Ashraf, M. & Li, H. The longitudinal shear bond behavior of an innovative laminated fiber reinforced composite slab. Constr. Build. Mater. 215, 508–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.04.153 (2019).

Zhang, X., Lou, C. & Lyu, X. Experimental study on direct tensile fatigue performance of basalt fiber reinforced concrete. Sci. Rep. 14, Article 765. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51403-1 (2024).

Xiao, Z. et al. Research on the fatigue performance of continuous beam bridges with vibration-mixed steel fiber-reinforced concrete. Sci. Rep. 14, Article 29927. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-79739-8 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Experimental study on mechanical properties and breakage of high temperature carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete under impact load. Sci. Rep. 14, Article 20566. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71292-8 (2024).

Pour, A. K. & Noroozinejad Farsangi, E. Effect of polypropylene fibers on the bond-slip performance of HSS bars in HPC and UHPC. Adv. Struct. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1177/13694332241266544 (2024).

Xia, Z. Y., Jiang, T. & Yu, T. Innovating arch structures with fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A review. Adv. Struct. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1177/13694332231180373 (2023).

Yoon, Y. S. & Yoo, D. Y. Influence of steel fibers and fiber-reinforced polymers on the impact resistance of one-way concrete slabs. J. Compos. Mater. 48 (6), 695–706. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021998313477167 (2014).

Caggiano, A., Gambarelli, S., Martinelli, E., Nisticò, N. & Pepe, M. Experimental characterization of the post-cracking response in hybrid steel/polypropylene fiber-reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 125, 1035–1043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.08.068 (2016).

Zhang, Y., Yang, Z., Zhang, H., Tsang, N. & Zhang, X. Improving the shear design of steel-bar reinforced ultra-high-performance fibre-reinforced concrete beams using mesoscale modelling. Adv. Struct. Eng. 26 (4), 724–740. https://doi.org/10.1177/13694332221137174 (2023).

Wang, R. & Zhang, P. Multi-objective optimization and mechanical properties analysis of steel–PVA hybrid fiber-reinforced cementitious composites. Materials 17 (17), Article 4324. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma17174324 (2024).

Sun, Y., Sun, Z., Fu, J., Cai, X. & Wu, G. Study on the deformation of hybrid BFRP-steel reinforced concrete beams considering crack development. Adv. Struct. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1177/13694332241298018 (2024).

Yassin, A. M., Mohie Eldin, M., Hafez, M. A. & Elnaggar, M. A. The flexural behavior and mechanical properties of super high-performance concrete (SHPC) reinforced using the hybridization of micro polypropylene and macro steel fibers. Buildings 14 (7), Article 1887. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14071887 (2024).

Saeed, H. Z., Saleem, M. Z., Chua, Y. S. & Vatin, N. I. Research on structural performance of hybrid ferro fiber reinforced concrete slabs. Materials 15 (19), Article 6748. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15196748 (2022).

Mohamad, N., Lakhiar, M. T., Yap, W. X., Samad, A. A. A. & Muthusamy, K. Structural performance of lightweight foamed concrete slab strengthening with fibres: A review. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1144(1), 012016. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/1144/1/012016 (2021).

Li, X., Zheng, X., Ashraf, M. & Li, H. Experimental study on the longitudinal shear bond behavior of lightweight aggregate concrete – Closed profiled steel sheeting composite slabs. Constr. Build. Mater. 156, 599–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.08.108 (2017).

Elsherbiny, E. A., Mortagi, M., Youssf, O., Abd Elrahman, M. & Madawy, M. E. E. Influence of steel and polypropylene fibers on the structural behavior of sustainable reinforced lightweight concrete beams made from crushed clay bricks. Sustainability 15 (19), 14570 (2023).

Youssf, O., Hassanli, R., Mills, J. E., Ma, X. & Zhuge, Y. Cyclic performance of steel–concrete–steel sandwich beams with rubcrete and LECA concrete core. J. Compos. Sci. 3 (1), 5 (2019).

Tahwia, A. M., Helal, K. A. & Youssf, O. Chopped basalt fiber-reinforced high-performance concrete: an experimental and analytical study. J. Compos. Sci. 7 (6), 250 (2023).

Acknowledgements

The first author and the corresponding author acknowledge Ho Chi Minh City Open University for supporting this study. The second author acknowledges Ho Chi Minh City University of Technology (HCMUT), Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City for supporting this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Khang Thanh Huong: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Experiment, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Linh Van Hong Bui: Supervision, Visualization, Methodology, Experiment, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Phuoc Trong Nguyen: Supervision, Visualization, Methodology, Experiment, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huong, K.T., Bui, L.V.H. & Nguyen, P.T. Experimental investigation on structural behavior of composite slabs with steel decking, fiber-reinforced concrete, and lightweight aggregate concrete layers. Sci Rep 15, 23786 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08955-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08955-7