Abstract

The invasive Aedes albopictus, commonly known as the Asian tiger mosquito, has spread globally, posing public health risks because of its role as a secondary vector for arboviruses and capacity to transmit pathogens across sylvatic and urban cycles. In Brazil, where Ae. aegypti remains the primary vector of dengue, Zika, and chikungunya viruses; Ae. albopictus is being increasingly monitored because of its ecological plasticity and potential to develop insecticide resistance. Here, we analyzed the genetic diversity of voltage-gated sodium channel (NaV) gene in Ae. albopictus populations across Brazil, in which knockdown resistance mutations (kdr) are associated with pyrethroid resistance. We collected Ae. albopictus from 46 Brazilian cities, extracted DNA from individual mosquitoes, and prepared pooled samples for next-generation sequencing. We targeted two NaV segments, regions commonly associated with kdr in other mosquito species: IIS6 and IIIS6 segments. High-throughput sequencing and bioinformatics analysis were used to assess haplotype diversity, distribution, and phylogenetic relationships. We identified 20 IIS6 and 24 IIIS6 haplotypes, indicating high genetic diversity within the NaV gene among Brazilian Ae. albopictus populations. No kdr mutations were detected despite the documented occurrence of these mutations in Ae. albopictus from other regions of the world. Nonetheless, we observed several synonymous polymorphisms, suggesting ancestral variation and potential for adaptive evolution. Our findings revealed substantial genetic diversity within the NaV gene in Brazilian Ae. albopictus populations but no current evidence of pyrethroid resistance-associated kdr mutations. The observed diversity provides a foundation for tracking shifts in allele frequencies that may affect insecticide susceptibility and vector competence. Continuous monitoring of genetic variation is essential to preemptively address the development of resistance in Ae. albopictus and mitigate potential public health risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse, 1894), commonly known as the Asian tiger mosquito, has garnered significant scientific and public health attention due to its global spread and role in arbovirus transmission1,2. A distinctive feature of Ae. albopictus is the chitinous serosa layer between the embryo and chorion eggshell, which enhances desiccation resistance and supports population expansion, particularly in urban environments3. Ranked among the world’s most invasive species, Ae. albopictus exhibits a remarkable capacity for propagation, posing epidemiological risks when it establishes populations2. Over the past four decades, this mosquito has spread from Southeast Asia to Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas, leaving Antarctica as the only unaffected continent. Genetic studies offering insights into its evolutionary trajectory trace its origins to the islands of the Western Pacific and Indian Oceans4. Trade navigation and more recently, climate and environmental changes have further broadened its geographic distribution, creating conditions for the expansion of its establishment in diverse regions5,6.

In Brazil, Ae. albopictus was first reported in Rio de Janeiro State7 and has since been detected across other states, raising concerns about its rapid spread and underscoring the importance of understanding its behavior and gene flow for effective control. Although Ae. aegypti remains the primary vector of arboviruses such as dengue (DENV), chikungunya (CHIKV), and Zika (ZIKV) in the Americas, Ae. albopictus has demonstrated the ability to transmit these viruses in specific regions of the globe4,8 and, notably, under controlled laboratory conditions9,10,11.

Unlike Ae. aegypti, Ae. albopictus exhibits a broader host range, feeding on various vertebrates, including reptiles and mammals, and its larvae can survive in both artificial and natural water reservoirs12,13. These traits suggest Ae. albopictus can act as a bridge for pathogen transmission between sylvatic and urban cycles2. Additionally, the species’ potential for vertical transmission of arboviruses, combined with photoperiodic diapause in temperate regions, supports virus persistence across seasons14,15,16.

Insecticide resistance presents a major global challenge for mosquito control, particularly with respect to resistance to pyrethroids, the most commonly used insecticide class for household mosquito control17. A primary mechanism conferring pyrethroid resistance across various insect orders involves mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene (NaV), commonly known as knockdown resistance mutations (kdr), which diminish susceptibility to the knockdown effect of pyrethroids18. The most well-characterized kdr mutations are single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that occur in the conserved regions of NaV. This channel is composed of four homologous domains (I-IV), each formed by six transmembrane segments (IS6-IVS6) that form the sodium channel pore of the excitable cells. Most kdr SNPs occur in the IIS6 and IIIS6 segments, generally at conserved sites. For example, substitutions at NaV sites 1016 (V1016G, IIS6) and 1534 (F1534C, IIIS6) were observed in both Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus17.

South America ranks among the world’s highest insecticide users for agricultural and public health purposes. For example, pesticide use has surged by 120% in the last 20 years19, with potentially serious implications for public health and the environment. Since 1999, a robust insecticide resistance monitoring program has been established in Brazil, accompanied by extensive studies on the molecular mechanisms underlying resistance20,21, however relatively few studies have focused on Ae. albopictus. Given the recent introduction and rapid spread of Ae. albopictus in Brazil, understanding the ecological and genetic factors driving insecticide resistance is critical for the design of effective control strategies. In this study, we examined the genetic diversity of two NaV gene segments in Ae. albopictus sampled from 46 localities in Brazil.

Methods

Mosquito collections

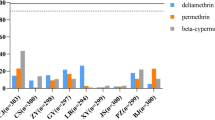

Mosquito sampling was conducted between 2017 and 2018, as part of a previous study aimed at monitoring the resistance of Aedes aegypti to the insecticides pyriproxyfen and malathion across Brazil. Eggs were collected using ovitraps installed in urban centers across 146 selected cities nationwide. Once collected, the eggs were shipped to the laboratory for further processing (see details in Campos et al., 202021). Upon arrival, the eggs hatched, larvae reared, and adult mosquitoes identified by species. Ae. albopictus was cryopreserved and used in this study. We selected a sample of 998 mosquitoes from 46 cities, including 11 cities in the north (n = 254), 11 in the northeast (n = 245), 11 in the southeast (n = 276), 10 in the Center-West (n = 175), and three in the south (n = 48). Supplemental Table S1 provides further information on the sampling locations, including city, state, geographic coordinates, and number of mosquito samples.

DNA extraction and population pool preparation

Each mosquito was placed in a 2 mL microtube containing 50 µL of buffer and two glass beads. Cells were lysed by shaking the samples vigorously for 1 min using TissueLyser II (Qiagen). Subsequent steps of the DNA extraction were performed using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The DNA concentration of each sample was measured using a NanoDrop One C (ThermoFischer Scientific) spectrophotometer, and samples were diluted to 20 ng/µL with ultra-pure water. To create the DNA pool for each population, we combined all individual DNA samples from the same locality (from 2 to 30 samples, with an average of 22 per locality) (Supplemental Table S1). Each pool was adjusted to contain 20 ng DNA.

Na V segments amplification

In other mosquito species, most mutations associated with knockdown resistance (kdr) are located in the gene exons encoding the IIS6 and IIIS6 segments. To explore polymorphism diversity in these regions, we designed specific primers to amplify these segments using Geneious Prime 2024.0.7 (http://www.geneious.com/), based on the sequence XM_029865132.1 from GenBank (NCBI) as a reference, and forward and reverse primers were designed to generate fragments of approximately 500 bp for IIIS6 segment and 400 bp for IIS6 segment. The IIS6 segment spans exons 20–21, and IIIS6 covers exons 30–31, with exon numbering based on Musca domestica NaV gene conventions. Illumina adapter sequences (hangers) were added to the 5’ends of both primers according to the 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation (version 15,044,223-B). Amplification of each region was performed independently for each population pool using the Phusion Hot Start Flex DNA Polymerase kit (BioLabs, New England), containing a high-fidelity enzyme. Each 25 µL PCR reaction included 60 ng of genomic DNA, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 × Phusion HF buffer, 200 µM dNTPs, 0.5 µM or 1 µM of each primer (for IIIS6 and IIS6, respectively), 1 U of polymerase (0.25 µL), 3% DMSO, and ultrapure water to reach the total volume. PCR cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 30 s; 35 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, annealing at 56 °C (IIS6) or 60 °C (IIIS6) for 15 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The primer sequences used are listed in Table 1.

NGS library preparation and sequencing

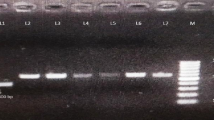

Amplicons from both NaV segments of each population pool were run on 1% agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm DNA bands of approximately 400 or 500 bp using a 1.5 kb molecular weight marker (NEB). The verified bands were excised and purified using the kGeneJET Gel Extraction Kit (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Equimolar amounts of purified amplicons from each population pool were combined. The quality and concentration of the pooled amplicons (IIS6 + IIIS6 mixture) were analyzed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer System (Agilent). A unique DNA barcode was added to each pool using the Nextera XT index kit (Illumina) in a PCR reaction with the KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix Kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing was performed on a MiSeq platform (Illumina) at the FIOCRUZ NGS facility using the MiSeq Reagent Kit v2 (500 cycles, paired-end, 2 × 250 bp).

Data analysis

Raw sequencing data were de-multiplexed using the SeekDeep pipeline22, which was used to trim primers and adapters, remove low-quality reads, make the sequence assembly, call haplotypes (sequences with 100% identity), and calculate haplotype frequencies within each population pool. To determine whether haplotypes were present in previous studies, each haplotype was used as a query in BLAST searches against the nucleotide (nt) database, retrieving only the best hits that covered the entire query sequence. All haplotypes were imported into Geneious Prime 2024.0.7 (http://www.geneious.com) and aligned using MUSCLE algorithm. Phylogenetic trees were constructed with IQ-TREE 223 using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura-Nei model selected by ModelFinder24, with branch support evaluated using 500 bootstrap replications. Haplotype networks were reconstructed in PopArt using TCS25.

Results

The DNA yield per mosquito was 1.1 ± 0.1 µg (mean ± standard deviation), which exceeded the quantity required for the molecular analyses. The remaining DNA was catalogued and stored at − 20 °C in the Brazilian Vector DNA Repository at FIOCRUZ for future research.

Sequence quality and filtering

Gel electrophoresis revealed two distinct bands at approximately 400 and 500 bp, confirming the successful amplification of the IIS6 and IIIS6 segments of the NaV gene. High-throughput sequencing generated 14.8 million paired reads, of which 11.7 million (79.1%) had a quality score greater than 30, indicating 99.9% accuracy. After demultiplexing, filtering low-quality reads, and off-target sequences, we retained 10.05 million sequences separated into the IIS6 and IIIS6 segments. Sequence lengths, haplotype frequencies, and GenBank accession numbers are listed in Table 2.

IIS6 segment Na V haplotypes

Haplotype analysis identified 20 distinct IIS6 haplotypes, with lengths ranging from 314 to 334 bp (Table 2, Fig. 1). The haplotypes showed greater than 90% identity with the reference sequence XM_029865132.1, confirming primer specificity. Multiple alignments revealed 60 polymorphic sites, of which 27 were informative. Twelve polymorphic sites within the coding region, eight in exon 20 and four in exon 21, all resulted in synonymous substitutions, indicating the absence of kdr mutations in our sampling. The remaining 48 polymorphic sites were located in intron 20 and included insertions and deletions (indels).

Nucleotide diversity of the voltage-gated sodium channel gene, IIS6 segment haplotypes, found in Aedes albopictus populations from Brazil. Geneious alignment among haplotypes found in this study (2s6.00-2s6.19), and consensus sequence generated by the software. Uppercase nucleotides correspond to the coding region (exons 20 and 21), while lowercase nucleotides refer to the intron, with alignment numbering at the top of each block. Invariable sites are indicated with dots, polymorphic sites with the alternative nucleotide, and gaps with (-). Codons in red represent codons 1016 where kdr mutations were previously described in Ae. albopictus. GenBank accession numbers of each haplotype are presented in Table 2.

Five unique synonymous substitutions were identified in exon 20 at codons 962 (GAC/GTA, 2s6.07), 968 (TTC/TTT, 2s6.16), 980 (GTG/GTA, 2s6.15), 993 (TGC/TGT, 2s6.07), and 1001 (TGT/TGC, 2s6.05), according to Musca domestica NaV codon numbering. Additional synonymous substitutions were shared among two or three haplotypes, specifically at codons 981 (CGG/CGA, 2s6.00 and 2s6.03), 1,006 (TTG/TTA, 2s6.08, and 2s6.12), and 993 (TGC/TGT, 2s6.00, 2s6.03, 2s6.16, and 2s6.07). The Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree (Fig. 2) and the haplotype network (Supplementary Fig. S1) of IIS6 haplotypes of Ae. albopictus suggest that the substitution at codon 1006 shared an ancestral origin, while those at 981 and 993 codons appeared to have emerged independently, given their presence in haplotypes with unrelated ancestors. The Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree did not reveal distinct clade groupings, unlikely that reported for Ae. aegypti26.

Phylogenetic relationship of the IIS6 haplotypes identified in Aedes albopictus populations from Brazil. Panel A–Maximum likelihood tree with bootstrap values exceeding 70%. Panel B–Alignment of intron 20, highlighting a region with greater sequence variation. Haplotypes were arranged in the same order as in the phylogenetic tree.

Haplotype 2s6.00 was found in 37 populations, making it the most frequent with 580,564 sequences (35.97%) (Table 2). The highest frequencies (73–98%) were observed in eight populations: four from the Center-West (Iporá—GO, Coxim—MS, Goiania—GO, and Dourados—MS), three from the Southeast (Belo Horizonte—MG, Angra dos Reis—RJ, and São Sebastião—SP), and one from the North (Redenção—PA, though where only two mosquitoes were sampled, limiting significance). In the other 29 populations, 2s6.00 ranged from moderate to low frequency (2.9–67%). The second most frequent haplotype, 2S6.02, represented by 355,901 sequences (20.5%), was found in 25 populations and was identical to OP940459.1 and KC152045 (GenBank accession numbers) reported in Chinese and Malay populations. It was prevalent in the northeast and absent from populations in the south and lower mid-west (Fig. 3). The third most frequent sequence was 2s6.01, with 145,155 sequences (9.64%) distributed across 32 populations. Similar to 2s6.00, was distributed countrywide; however, it was scarcely found in northeastern populations, except in Nossa Senhora da Glória (SE) and Brumado (BA). The fourth most frequent haplotype, 2s6.3, with 134,723 sequences (7.66%), was identical to OP941111.1, previously reported in China, and was predominantly found in the north, upper Center-West (Brasília and Água Boa), and southeast coasts (Rio de Janeiro and Espírito Santo) (Fig. 3).

Sixteen additional haplotypes had frequencies < 5%. Among them, five (2s6.6, 2s6.9, 2s6.11, 2s6.13, and 2s6.15) were identical to the haplotypes identified in China, suggesting that multiple migration events may have introduced them into the Brazilian gene pool. The 2s6.11 was restricted to the north, while the other four were distributed across multiple regions (Fig. 3). Interestingly, haplotypes 2s6.14, 2s6.16, and 2s6.17 were found exclusively in the state of Espírito Santo. This pattern suggests that these haplotypes either originated locally or were introduced into the gene pool through recent migration. Using the Maximum Likelihood tree, haplotype 2s6.17 shares the same ancestor with 2s6.04, and haplotype 2s6.16 with 2s6.00 (Fig. 2), both of which are widely distributed (Table 2, Supplemental Fig. S1).

IIIS6 segment Na V haplotypes

We identified 24 haplotypes in the IIIS6 NaV segment of Ae. albopictus samples (Fig. 4), corresponding to the exons 30 and 31 flanking the intron 30, and sequences ranging from 415 to 431 nucleotides, given indels in the intron. The most prevalent haplotype, 3s6.00, accounted for 67.8% of the IIIS6 sequences (626,082 reads) and was widely distributed across all populations, excluding Brumado (BA), likely because of the small sample size from this location (two individuals). Following, haplotype 3s6.01 was found at a frequency of 9.5% and present in 31 populations, and 3s6.02, with a frequency of 4.52%, was identified in 29 populations. The remaining 17 haplotypes were rare in our sample, with a frequency of < 1%. Of particular note, haplotype 3s6.23 (0.09%) was exclusive to populations in Rio de Janeiro State, while haplotype 3s6.16 was found only in populations from Espírito Santo State, supporting the hypothesis of unique evolutionary dynamics in Ae. albopictus populations from this region, potentially involving diverse origins and new introductions.

Nucleotide diversity in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene, IIIS6 segment, in Aedes albopictus populations from Brazil. Alignment among haplotypes found in this study (3s6.00-3s6.23) and consensus sequence generated by Geneious software. Uppercase nucleotides correspond to the coding region (Exons 30 and 31), while lowercase nucleotides refer to the intron, with alignment numbering at the top of each block, and primer position sequences underlined. Invariable sites are indicated with dots, polymorphic sites with the alternative nucleotide, and gaps with (-). Codons in red represent codons 1520, 1532, and 1534 where kdr mutations were found in Ae. albopictus from elsewhere. The Genbank accession numbers of each haplotype sequence are available in Table 2.

The populations displayed varied haplotype profiles, ranging from one haplotype in Santa Maria (RS, South) to nine haplotypes in Posse (GO, Center-West) (Fig. 3). Compared to the available Ae. albopictus IIIS6 NaV sequences from other countries, the haplotype 3s6.15, observed in Porto Velho, Cacoal (RO), and Londrina (PR), was identical to that of KC152046 (GenBank accession number) from a sample in Malaysia. The low bootstrap values in the phylogenetic tree analysis (Fig. 5) prevented clear division of IIIS6 haplotypes into distinct groups. In addition, the haplotype network exhibited a complex structure (Supplemental Fig. S2).

Phylogenetic relationship of the IIIS6 haplotypes identified in Aedes albopictus populations from Brazil. Panel A–Maximum likelihood tree with bootstrap values exceeding 70%. Panel B–Alignment of intron 30, highlighting a region with greater sequence variation. Haplotypes were arranged in the same order as in the phylogenetic tree.

We did not detect a kdr mutation nor any other non-synonymous substitution in the IIIS6 NaV segment. However, eight polymorphic codons were identified within exons 30 and 31 of NaV. The polymorphism at codon 1,505 (GAT/GAC) in exon 30 was present in haplotypes 3s6.07, 3s6.16, and 3s6.18. In exon 31, polymorphism at codon 1,516 (CCG/CCA) was found in haplotypes 3s6.06, 3s6.08, 3s6.12, 3s6.16, and in the most derivate haplotype 3s6.20. Codon 1,528 polymorphism (TTC/TTT) was shared among haplotypes 3s6.01, 3s6.02, 3s6.07, 3s6.09, 3s6.14, and 3s6.21. Polymorphism at codon 1,514 (AAG/AAA) was identified in haplotype 3s6.02 (Figs. 3, 4, and 5).

Phasing IIS6 and IIIS6 haplotypes

As we sequenced pooled DNA samples, we determined which IIS6 and IIIS6 haplotypes were phased (i.e., present on the same chromosome) only in populations where at least one segment was monomorphic. This criterion applies only to the Maceió (with the IIS6 segment monomorphic for haplotype 2s6.00) and Santa Maria (with the IIIS6 segment monomorphic for haplotype 3s6.00) populations. Based on these data, we propose that the six phased IIS6 + IIIS6 haplotypes may be present in Brazilian Ae. albopictus populations: (1) 2s6.00_B + 3s6.00, (2) 2s6.00_B + 3s6.01, (3) 2s6.00_B + 3s6.05, (4) 2s6.00_B + 3s6.07, (5) 2s6.01_A + 3s6.00, and (6) 2s6.04_B + 3s6.00 (Fig. 6). Therefore, the phased combination of haplotypes 2s6.00_B + 3s6.00 is likely the most common phased haplotype circulating within Ae. albopictus populations in Brazil.

Phased haplotypes of IIS6 and IIIS6 segments of the NaV gene in Aedes albopictus populations from Brazil. Six distinct phasings were identified when at least one segment was monomorphic in a population. Bars represent alignments of the IIS6 and IIIS6 sequences, highlighting the polymorphisms. Synonymous codon changes are indicated.

Discussion

Ae. albopictus is an invasive species first recorded in Brazil in 1986. National entomological surveillance and insecticide resistance (IR) monitoring by the Brazilian government primarily targets Ae. aegypti, the recognized vector of dengue, chikungunya, and Zika viruses27,28. Consequently, research on Ae. albopictus biology, physiology, and genetics have been comparatively limited, in contrast to the extensive studies on Ae. aegypti. In terms of IR, Ae. aegypti has been systematically monitored in Brazil since 1999, with studies detailing the phenotypic profiles, molecular mechanisms of resistance, and fitness effects associated with resistance selection20,29. Molecular surveillance of kdr mutations, a key mechanism related to pyrethroid resistance, has provided substantial data regarding the distribution of resistance alleles in Ae. aegypti populations in Brazil. Over 130 Ae. aegypti populations from Brazil30,31,32,33,34,35 have been assessed for kdr frequencies, whereas only a few studies have evaluated the IR phenotype in Ae. albopictus17. To date, there are no records of kdr mutations in this species in Brazil.

In this study, we analyzed the diversity of sequences from the IIS6 and IIIS6 segments of the voltage-gated sodium channel (NaV) of Ae. albopictus populations across Brazil using high-throughput sequencing on a national scale. Our analysis revealed high genetic diversity within the NaV gene of Brazilian Ae. albopictus, with 20 different IIS6 and 24 different IIIS6 haplotypes identified. These segments harbor key kdr mutations in several insect species, including Ae. albopictus36,37,38. Although we did not detect any kdr-related mutations, we observed significant haplotype diversity, detailing their phylogenetic relationships, frequencies, and geographic distributions. These data provide valuable information regarding the evolutionary dynamics of this invasive species in Brazil.

We observed that nucleotide diversity in NaV homologous sequences was higher in Ae. albopictus than Ae. aegypti, considering the Brazilian26 and Pakistani39 populations despite the broader range of kdr mutations and larger available NaV sequences reported in Ae. aegypti40. The F1,534C kdr mutation is prevalent in Ae. aegypti populations across America, Africa, and Asia have also been found in Ae. albopictus in Singapore41, Greece42, and India43. Interestingly, several other substitutions at codons 1534 were identified only in Ae. albopictus, including F1,534S (China and USA37), F1,534L (USA44, Italy, and China38), and F1,534W and F1,534R (China45). The V1,016G kdr mutation commonly observed in Ae. aegypti populations from Asia have also been found in Ae. albopictus populations in China46, Vietnam and Italy47.

Previous studies on Ae. albopictus NaV diversity examined the portions of domains II, III, and IV of this channel from samples collected in various countries. This study identified 29 synonymous substitutions with no changes at the homologous kdr sites (989, 1011, and 1016) observed in Ae. aegypti. Instead, the mutation I1532T was found in samples from Italy, F1534S in China and the USA, F1534L in China, and F1534C in Greece37. Interestingly, we did not observe any non-synonymous substitutions despite examining Ae. albopictus samples from 46 urban centers in Brazil with an average sequencing depth coverage of 119.5X. It is noteworthy, however, that while Ae. albopictus populations in Brazil may not be resistant to pyrethroids, and IR and kdr mutations are widespread in sympatric Ae. aegypti populations33, suggesting similar environmental selection pressure. Phenotypic characterization of insecticide susceptibility and resistance to insecticides is required for Ae. albopictus from Brazil.

In Brazil, at least two kdr alleles are widespread in Ae. aegypti populations: kdr R1 (F1534C only) and the kdr R2 (V410L + V1016I + F1534C)26,33,35. Despite the high diversity of NaV haplotypes in Ae. albopictus, we found no kdr mutation. A similar pattern was observed in Asian populations of both species, Ae. albopictus lacks kdr mutations, whereas Ae. aegypti showed mutations such as T1,520I and F1,534C in Pakistan39 and V1,1016G and F1,534C in Malaysia48. The pyrethroid-resistant phenotype of Ae. albopictus without kdr mutations has been attributed to metabolic resistance mechanisms, particularly through the overexpression of cytochrome P450 genes, such as CYP6P12 in Malaysian49 and Cameroonian50 populations.

The introduction of Ae. albopictus in Brazil likely occurred in the 1980s, possibly through iron trade ships from Japan that arrived at the ports of Espírito Santo. Multiple additional introductions may have subsequently occurred51,52,53. The presence of numerous NaV haplotypes, including some unique to localities in Espírito Santo (e.g., 2s6.16, 2s6.17, and 3s6.16), supports the hypothesis of multiple introductions. Additionally, haplotype 3s6.15 (identical to the Malaysian sequence KC152046 in GenBank) was detected in both the northern (Roraima) and southern (Paraná) regions of Brazil, which are separated by over 3,100 km. If this haplotype is not widely dispersed in Brazil, it may suggest independent introduction from Asia at different times. Further studies using neutral markers will help to clarify the origins and spread of these haplotypes.

Even if Ae. albopictus populations in Brazil are not currently resistant to pyrethroids; the genetic diversity observed in this species provides a potential reservoir for selecting variants that are favorable to resistance. Moreover, the continuous introduction of Ae. albopictus from regions with established resistance, new alleles could be introduced. This highlights the need for sanitary authorities to monitor the IR and genetic diversity in Ae. albopictus. Although this species is not officially recognized as a major arbovirus vector in Brazil, it has the potential to serve as a bridge vector between sylvatic and urban pathogens owing to its ecological plasticity2,10. Thus, the continuous monitoring of Ae. albopictus populations in Brazil are warranted to detect emerging genetic profiles that may favor either insecticide resistance or enhanced vector competence54.

Conclusion

This study used NGS to reveal substantial diversity in the IIS6 and IIIS6 NaV segments of Ae. albopictus populations across Brazil, identifying 20 and 24 haplotypes, respectively, with no evidence of kdr mutation. Certain haplotypes were unique to specific regions, suggesting a limited gene flow. Overall, these findings provide valuable insights into the genetic diversity and structure of Ae. albopictus in Brazil, which is essential for the development of effective vector control strategies. Continuous monitoring is recommended to track potential changes in genetic profiles that may be related to public health risks such as insecticide resistance and vector competence.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are freely available in the Zenodo repository at https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14624090. The haplotype consensus sequences have been deposited in GenBank (NCBI, NIH) and can be accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/. The accession numbers of each haplotype are listed in Table 2.

References

Paupy, C., Delatte, H., Bagny, L., Corbel, V. & Fontenille, D. Aedes albopictus, an arbovirus vector: from the darkness to the light. Microbes Infect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2009.05.005 (2009).

Pereira-Dos-Santos, T., Roiz, D., Lourenco-de-Oliveira, R. & Paupy, C. A systematic review: Is Aedes albopictus an efficient bridge vector for zoonotic arboviruses?. Pathogens https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9040266 (2020).

Farnesi, L. C., Menna-Barreto, R. F., Martins, A. J., Valle, D. & Rezende, G. L. Physical features and chitin content of eggs from the mosquito vectors Aedes aegypti, Anopheles aquasalis and Culex quinquefasciatus: Connection with distinct levels of resistance to desiccation. J. Insect. Physiol. 83, 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinsphys.2015.10.006 (2015).

Gratz, N. G. Critical review of the vector status of Aedes albopictus. Med. Vet. Entomol. 18(3), 215–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0269-283X.2004.00513.x (2004).

Kraemer, M. U. et al. The global compendium of Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus occurrence. Sci. Data https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2015.35 (2015).

Kraemer, M. U. G. et al. Past and future spread of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Nat. Microbiol. 4(5), 854–63. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-019-0376-y (2019).

Sant’Ana, A. L. First recorded occurrence of Aedes (Stegomyia) albopictus (Skuse) in the southeastern region of Brazil. Rev. Saude Publ. 30(4), 392–393. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-89101996000400013 (1996).

Kobayashi, D. et al. Dengue virus infection in Aedes albopictus during the 2014 Autochthonous dengue outbreak in Tokyo metropolis, Japan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 98(5), 1460–8. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.17-0954 (2018).

Vega-Rua, A., Zouache, K., Girod, R., Failloux, A. B. & Lourenco-de-Oliveira, R. High level of vector competence of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus from ten American countries as a crucial factor in the spread of Chikungunya virus. J. Virol. 88(11), 6294–306. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00370-14 (2014).

Couto-Lima, D. et al. Potential risk of re-emergence of urban transmission of Yellow Fever virus in Brazil facilitated by competent Aedes populations. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 4848. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05186-3 (2017).

Lourenco-de-Oliveira, R., Vazeille, M., de Filippis, A. M. & Failloux, A. B. Aedes aegypti in Brazil: genetically differentiated populations with high susceptibility to dengue and yellow fever viruses. Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 98(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0035-9203(03)00006-3 (2004).

Faraji, A. et al. Comparative host feeding patterns of the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, in urban and suburban Northeastern USA and implications for disease transmission. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 8(8), e3037. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0003037 (2014).

Bonizzoni, M., Gasperi, G., Chen, X. & James, A. A. The invasive mosquito species Aedes albopictus: current knowledge and future perspectives. Trends Parasitol. 29(9), 460–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2013.07.003 (2013).

Angel, B. & Joshi, V. Distribution and seasonality of vertically transmitted dengue viruses in Aedes mosquitoes in arid and semi-arid areas of Rajasthan, India. J, Vector Borne Dis. 45(1), 56–59 (2008).

Serufo, J. C. et al. Isolation of dengue virus type 1 from larvae of Aedes albopictus in Campos Altos city, State of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 88(3), 503–504. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0074-02761993000300025 (1993).

Ferreira-de-Lima, V. H. et al. Silent circulation of dengue virus in Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) resulting from natural vertical transmission. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 3855. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60870-1 (2020).

Moyes, C. L. et al. Contemporary status of insecticide resistance in the major Aedes vectors of arboviruses infecting humans. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11(7), e0005625. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005625 (2017).

Zhorov, B. S. & Dong, K. Elucidation of pyrethroid and DDT receptor sites in the voltage-gated sodium channel. Neurotoxicology. 60, 171–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2016.08.013 (2017).

Maennel, A. & Böll-Stiftung, Heinrich. The Pesticide Atlas – Facts and Figures about Toxic Chemicals in Agricultural (US Edition, 2023).

Valle, D., Bellinato, D. F., Viana-Medeiros, P. F., Lima, J. B. P. & Martins Junior, A. J. Resistance to temephos and deltamethrin in Aedes aegypti from Brazil between 1985 and 2017. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz https://doi.org/10.1590/0074-02760180544 (2019).

Campos, K. B. et al. Assessment of the susceptibility status of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) populations to pyriproxyfen and malathion in a nation-wide monitoring of insecticide resistance performed in Brazil from 2017 to 2018. Parasit. Vectors 13(1), 531. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04406-6 (2020).

Hathaway, N. J., Parobek, C. M., Juliano, J. J. & Bailey, J. A. SeekDeep: single-base resolution de novo clustering for amplicon deep sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 46(4), e21 (2018).

Minh, Bui Quang et al. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37(5), 1530–1534. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa015 (2020).

Kalyaanamoorthy, S. et al. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 14, 587–589. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4285 (2017).

Clement, M., Posada, D. & Crandall, K. A. TCS: a computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Mol. Ecol. 9(10), 1657–1659. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01020.x (2000).

Cosme, L. V., Gloria-Soria, A., Caccone, A., Powell, J. R. & Martins, A. J. Evolution of kdr haplotypes in worldwide populations of Aedes aegypti: Independent origins of the F1534C kdr mutation. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14(4), e0008219. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008219 (2020).

Medeiros, A. S. et al. Dengue virus in Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in urban areas in the state of Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil: Importance of virological and entomological surveillance. PLoS ONE 13(3), e0194108. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194108 (2018).

Degallier, N. et al. Aedes albopictus may not be vector of dengue virus in human epidemics in Brazil. Rev. Saude Publ. 37(3), 386–7. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-89102003000300019 (2003).

Martins, A. J. et al. Effect of insecticide resistance on development, longevity and reproduction of field or laboratory selected Aedes aegypti populations. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0031889 (2012).

Brito, L. P., Carrara, L., de Freitas, R. M., Lima, J. B. P. & Martins, A. J. Levels of resistance to Pyrethroid among distinct kdr alleles in Aedes aegypti laboratory lines and frequency of kdr Alleles in 27 natural populations from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2410819. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2410819 (2018).

Linss, J. G. et al. Distribution and dissemination of the Val1016Ile and Phe1534Cys Kdr mutations in Aedes aegypti Brazilian natural populations. Parasit. Vectors https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-25 (2014).

Macoris, M. L., Martins, A. J., Andrighetti, M. T. M., Lima, J. B. P. & Valle, D. Pyrethroid resistance persists after ten years without usage against Aedes aegypti in governmental campaigns: Lessons from Sao Paulo State, Brazil. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12(3), e0006390. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006390 (2018).

Melo Costa, M. et al. Kdr genotyping in Aedes aegypti from Brazil on a nation-wide scale from 2017 to 2018. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 13267. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70029-7 (2020).

Dolabella, S. S. et al. Detection and distribution of V1016Ikdr mutation in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene in Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) populations from Sergipe State, Northeast Brazil. J. Med. Entomol. 53(4), 967–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjw053 (2016).

Souza, B. S. et al. Genetic structure and kdr mutations in Aedes aegypti populations along a road crossing the Amazon Forest in Amapa State, Brazil. Sci. Rep. 13(1), 17167. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44430-x (2023).

Auteri, M., La Russa, F., Blanda, V. & Torina, A. Insecticide resistance associated with kdr mutations in Aedes albopictus: An update on worldwide evidences. Biomed. Res. Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3098575 (2018).

Xu, J. et al. Multi-country survey revealed prevalent and novel F1534S mutation in voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) gene in Aedes albopictus. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10(5), e0004696. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0004696 (2016).

Pichler, V. et al. A novel allele specific polymerase chain reaction (AS-PCR) assay to detect the V1016G knockdown resistance mutation confirms its widespread presence in Aedes albopictus populations from Italy. Insects https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12010079 (2021).

Rahman, R. U. et al. Insecticide resistance and underlying targets-site and metabolic mechanisms in Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus from Lahore, Pakistan. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 4555. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83465-w (2021).

Corbel, V. et al. Tracking insecticide resistance in mosquito vectors of arboviruses: The worldwide insecticide resistance network (WIN). PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10(12), e0005054. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005054 (2016).

Kasai, S. et al. First detection of a putative knockdown resistance gene in major mosquito vector, Aedes albopictus. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 64(3), 217–221 (2011).

Fotakis, E. A. et al. Population dynamics, pathogen detection and insecticide resistance of mosquito and sand fly in refugee camps, Greece. Infect. Dis. Pov. 9(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-020-0635-4 (2020).

Modak, M. P. & Saha, D. First report of F1534C kdr mutation in deltamethrin resistant Aedes albopictus from northern part of West Bengal, India. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 13653. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-17739-2 (2022).

Marcombe, S., Farajollahi, A., Healy, S. P., Clark, G. G. & Fonseca, D. M. Insecticide resistance status of United States populations of Aedes albopictus and mechanisms involved. PLoS ONE 9(7), e101992. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0101992 (2014).

Chen, H. et al. The pattern of kdr mutations correlated with the temperature in field populations of Aedes albopictus in China. Parasit. Vectors 14(1), 406. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04906-z (2021).

Zhou, X. et al. Knockdown resistance (kdr) mutations within seventeen field populations of Aedes albopictus from Beijing China: first report of a novel V1016G mutation and evolutionary origins of kdr haplotypes. Parasit. Vectors 12(1), 180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3423-x (2019).

Kasai, S. et al. First detection of a Vssc allele V1016G conferring a high level of insecticide resistance in Aedes albopictus collected from Europe (Italy) and Asia (Vietnam), 2016: a new emerging threat to controlling arboviral diseases. Euro Surveill. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.5.1700847 (2019).

Ishak, I. H., Jaal, Z., Ranson, H. & Wondji, C. S. Contrasting patterns of insecticide resistance and knockdown resistance (kdr) in the dengue vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus from Malaysia. Parasit. Vectors 8, 181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-015-0797-2 (2015).

Ishak, I. H. et al. The Cytochrome P450 gene CYP6P12 confers pyrethroid resistance in kdr-free Malaysian populations of the dengue vector Aedes albopictus. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24707 (2016).

Yougang, A. P. et al. Nationwide profiling of insecticide resistance in Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Cameroon. PLoS ONE 15(6), e0234572. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0234572 (2020).

Lourenco de Oliveira, R., Vazeille, M., de Filippis, A. M. & Failloux, A. B. Large genetic differentiation and low variation in vector competence for dengue and yellow fever viruses of Aedes albopictus from Brazil, the United States, and the Cayman Islands. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 69(1), 105–14 (2003).

Kotsakiozi, P. et al. Population genomics of the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus: insights into the recent worldwide invasion. Ecol. Evol. 7(23), 10143–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.3514 (2017).

Ayres, C. F., Romao, T. P., Melo-Santos, M. A. & Furtado, A. F. Genetic diversity in Brazilian populations of Aedes albopictus. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 97(6), 871–875. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0074-02762002000600022 (2002).

Lambrechts, L., Scott, T. W. & Gubler, D. J. Consequences of the expanding global distribution of Aedes albopictus for dengue virus transmission. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4(5), e646. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0000646 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the CGARB, Ministry of Health/Brazil, for their efforts in funding and organizing the nationwide collections of Aedes eggs for the Aegypti aegypti insecticide resistance monitoring, from which we obtained the Ae. albopictus samples were used in this study. We are also grateful to the team at the NGS facility at FIOCRUZ for their support.

Funding

This study was made possible through funding provided by Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq)—grant # 316730/2021-1; Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ)—grant # E-26/210.067/2023; and Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia em Entomologia Molecular (INCT-EM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AJM, GJN, JBPL and LVC contributed to the design and implementation of the research, GJN, ALQT to the analysis of the results, GJN, AJM, JBPL, LVC, ALQT to the writing and revision of the manuscript. AJM conceived the original and supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical compliance

The Institute of Oswaldo Cruz has received accreditation for carrying out experiments with wild and urban mosquitoes kept as colonies in insectaries. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee on Animal Use (CEUAIOC-License LO28/18) of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute, FIOCRUZ.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nascimento, G.J., Cosme, L.V., Torres, A.L.Q. et al. High voltage-gated sodium channel gene diversity in Aedes albopictus across Brazil. Sci Rep 15, 20832 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08989-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-08989-x