Abstract

Organic rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivation represents a pathway toward sustainable agriculture. Soil microbial communities vary with topographic features, potentially affecting organic fertilizer efficiency and crop productivity, yet the relationship between topography, soil microbes, and fertilizer performance in rice farming remains largely unexplored. On-farm trials were conducted at two locations with contrasting topography (valley bottom vs. hillslope) in Yosano Town, Japan, comparing rice plant nitrogen uptake, biomass production, and grain yields under organic fertilizer management. Soil incubation experiments and microbiome analyses were performed to investigate differences in nitrogen mineralization rates and soil microbial community composition between locations. Valley bottom fields showed higher nitrogen uptake, biomass production, and grain yield with organic fertilizer application compared to hillslope fields. These differences are associated with higher nitrogen mineralization rates and lower abundance of genes involved in denitrification and bacterial ammonia assimilation in valley bottom soils, suggesting greater nitrogen retention and plant availability. These findings provide insights into site-specific management of organic fertilizers in rice production, highlighting the need for tailored strategies based on local topographic conditions and associated soil microbial communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rice (Oryza sativa L.), a major cereal crop, has seen significant yield increases due to intensive farming practices. However, the heavy use of agricultural inputs has raised environmental concerns, leading to a growing interest in organic rice farming1,2. Nitrogen is the most critical nutrient for rice production in paddy fields3,4, but developing efficient nitrogen management strategies for organic farming remains challenging due to the complex role of soil microbes in nitrogen cycling.

Soil microbial communities and their functions are strongly influenced by topographic features at both landscape and microtopographic scales5,6,7,8. For example, downslopes and depressions tend to have higher denitrification rates due to the accumulation of water and organic matter9,10,11. These topography-induced variations in soil microbes have been shown to affect crop productivity and nutrient use efficiency in various agroecosystems12,13,14,15. However, the potential impact of topographic heterogeneity on the performance of organic fertilizers in rice farming systems remains largely unexplored, despite the historical prevalence of complex topography in rice agroecosystems worldwide, such as terraced fields and valley bottoms16,17.

Here, we hypothesize that the effect of organic fertilizer on rice growth and yield varies with the location within a rice farming community due to topography-induced differences in soil microbial populations. While previous studies have examined either topographic effects on soil microbes or organic fertilizer performance in rice separately, our study is the first to integrate these factors to understand their interaction in farming systems. To test this hypothesis, we conducted on-farm trials at two locations with contrasting topography (valley bottom vs. hillslope) in Yosano Town, Japan18, comparing rice plant nitrogen uptake, biomass production, and grain yields under organic fertilizer management. We also performed soil incubation experiments to compare nitrogen mineralization rates and conducted microbiome analyses to investigate the differences in soil microbial community composition and nitrogen-cycling functions between the two locations.

By integrating field, laboratory, and molecular approaches, this study aims to provide novel insights into the site-specific management of organic fertilizers in rice production. Our findings reveal how topographic variations within a single farming community can significantly affect soil microbial communities and nitrogen cycling, potentially determining organic fertilizer efficiency. These results may contribute to the development of sustainable and environmentally-friendly rice farming practices that optimize the use of organic inputs based on local topographic conditions and their associated soil microbial communities, ultimately supporting the expansion of organic rice farming.

Materials and methods

On-farm trial

Site description

On-farm field trials were conducted in Yosano town, northern Kyoto, Japan18 between April and September in 2020 and 2021 (Fig. 1a). While forests mostly occupy the town, an alluvial fan formed by the Noda River accommodates approximately 880 ha of rice fields on narrow, flat areas with gentle slopes (Fig. 1b). Archaeological evidence indicates rice has been cultivated in the area for more than 1200 years. In this region, daily mean temperatures usually start exceeding 10 °C around late March, and relatively high temperatures suitable for rice production continue until early October (Supplementary Fig. 1). Daily temperatures, rainfalls, and sunshine hours recorded in 2020 and 2021were obtained from the Miyazu Meteorological Observatory of Japan Meteorological Agency (Table 1). Rice fields in Yosano town are widely grown with Koshihikari, a rice cultivar most widely grown in Japan in 2022. In the last decade, organic farming has been promoted by the Yosano Municipal Government, and many farmers have applied organic fertilizers to their rice fields. The municipal government operates a fertilizer factory that produces a type of organic fertilizer called Mamekko. Mamekko is a mixture of rice bran, soy pulp, and fish waste, which are by-products of the regional food industry. The composition of each material in Mamekko is carefully determined based on chemical analysis to supply a balanced set of nutrients (Supplementary Table 1).

Trial fields

Trial fields were selected from two villages: Kaya and Ishikawa. Kaya is located 22.4 m above sea level on average, while Ishikawa is 5.3 m above sea level on average (Fig. 1c). In both villages, Mamekko had been used in rice cultivation in the last decade. Before introducing water for puddling, soil sample was collected from each field (Fig. 2a) and examined for chemical and physical properties (Table 2) and available nitrogen. Six paddy fields were selected from both Kaya and Ishikawa villages and randomly assigned to six levels (0–0, 1–0, 1–1, 2–0, 2–1, and 3–0) of fertilizer treatment (Table 3). Four farmers, three from Kaya and one from Ishikawa, who owned the lands, took responsibility for the rice production under close supervision by the Yosano Municipal Government. The implementation timing and technique for each cultivation practice was decided by each farmer based on their individual management plans. This approach allowed the evaluation of the effect of Mamekko fertilizer on rice plant performance under actual farming conditions.

Sampling scheme of soils and plants. (a) Pre-transplanting in 2020/2021: Soil columns (0.1 m diameter × 0.15 m length) were collected from 5 positions per field, combined into a field composite, and analyzed for physicochemical properties and available nitrogen. (b) During transplanting to maturity: Soil columns (0.02 m diameter × 0.15 m length) were collected from 8 positions per field at 2-week intervals and analyzed for ammonium and nitrate nitrogen content. (c) Post-maturity in 2020: Four hills were sampled at harvest to measure dry matter weight and nitrogen content. (d) During transplanting to maturity in 2021: Four hills were sampled at 2-week intervals to measure dry matter weight and nitrogen content. (e,f) Post-maturity: 52 hills were sampled at harvest to measure yield and yield components in 2020 and 2021. (g) Pre-transplanting in 2023: Soil columns (0.1 m diameter × 0.15 m length) were collected from 8 positions per field for microbial analysis and available nitrogen measurement in the incubation experiment. (h) In 2023: Field composites were prepared by combining soil samples from each village (Kaya: 0–0, 1–0, 1–1, 2–0, 2–1 and Ishikawa: 0–0, 1–0, 1–1, 2–0) for soil incubation studies across different fertilization treatments.

Measurement

Soils were sampled from the top soil at approximately two-week intervals throughout the growing season of 2020 and 2021 (Fig. 2b). Ammonium (NH4-N) and nitrate nitrogen (NO3-N) contents in the soil were determined using an absorptiometer (DR600, Hach, USA) with extracts obtained from KCl solution and distilled water. NH4-N extracted with KCl solution was regarded as the total amount of NH4-N, while NH4-N extracted with distilled water was regarded as the dissolved fraction. All NO3-N was assumed to be in the dissolved phase.

Plants were sampled from above the ground once at harvest in 2020 (Fig. 2c) and eight times at approximately two-week intervals throughout the growth period in 2021 (Fig. 2d). At each sampling event, four hills with moderate shoot growth were selected from each field, and the shoots of each hill were uprooted from the soil. After removing soils from the stem bases under running water, nodal (adventitious) roots developing from the stem bases were removed from the stems. The remaining shoot samples were separated into leaf blades, stems (culms and leaf sheath), and panicles. The separated shoot samples were dried at 55 °C for 72 h until they reached a constant weight, and shoot dry matter weight (t ha−1) was calculated from the dry matter weight of the shoot parts and planting density. Nitrogen content of the shoot parts (%) were determined using an elemental analyzer (Vario EL cube, Elementar, Germany), and shoot nitrogen content (kg ha−1) was calculated from the nitrogen content of the shoot parts (%) and shoot dry matter weight (t ha−1).

Additional plants were sampled from above the ground at harvest in the both years (Fig. 2e,f). At each event, 52 hills, 4 hills from 13 different positions within each field, with moderate shoot growth were cut at the stem bases, and the shoot samples with panicles were air-dried for approximately two weeks. The panicles were threshed, and the paddies were hulled to obtain rough brown rice. The rough brown rice was sieved using a grain sorter with a sieve size of 1.8 mm. The sieved grains were weighed, and their moisture content was measured using a rice moisture tester (PM-670–2; Kett, Tokyo, Japan). The grain yield (t ha−1) adjusted to 15% moisture content was calculated from the weight and moisture content of the sieved grains and planting density.

Analysis

The on-farm trials were conducted using a randomized complete block design with repeated measures (Table 3), where the six levels of fertilizer treatment were assigned to fields in each of the two villages (location), and the same treatments were repeated in the same paddy fields in two consecutive years. Response variables such as shoot nitrogen content, shoot dry matter, and grain yield were regressed on explanatory variables such as fertilizer treatment (Fert) and trial year (Year) as fixed effects with location and fields as random effects. After evaluating several models, parameters were estimated using a Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) with a nested random effect, modelled as follows:

where Yijkl represents the response variable (nitrogen content, dry matter weight, brown rice yield) for the i-th fertilizer treatment at the j-th location in the l-th field within that location in the k-th year. The fixed effects are: β0 (intercept), β1Ferti (effect of fertilizer treatment), β2Yeark (effect of year). The random effects include: uj (effect of location), and vjl (effect of field nested within location), while εijkl represents the residual error. All randome effects are assumed to be normally distributed with mean 0 and their respective variances. Alternative model structures were also evaluated, including: (i) models with only location as a random effect, (ii) models with only field as a random effect, and (iii) models with fertilizer-by-location interaction as a fixed effect. Model selection was performed using Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and AICs (corrected for small sample sizes). The nested random effect model was selected as it appropriately accounted for the hierarchical structure of the experimental design while maintaining model parsimony. To further interpret the random effects, conditional means (Best Linear Unbiased Predictions, BLUPs) for locations were extracted from the model to quantify the effects of topographic position (valley bottom vs. hillslope) on the response variables. Model diagnostics, including checks for normality and homoscedasticity of residuals, were performed to ensure the assumptions were met. The proportion of variance explained by the model was evaluated using both marginal R2 (variance explained by fixed effects) and conditional R2 (variance explained by both fixed and random effects). These statistical analyses were performed using the R software (version 4.4.1) with the “lmer” function from the “lme4” and “lmerTest” packages for mixed effect model estimates and significance tests. The “effects” package was used for visualizing model predictions, and the “MuMIn” package was used for calculating R2 values.

Soil incubation experiment

Soil incubation

Soils were sampled from five fields in Kaya (0–0, 1–0, 1–1, 2–0, and 2–1 treatments, see Table 3) and four fields in Ishikawa (0–0, 1–0, 1–1, and 2–0 treatments, see Table 3) before introducing water for puddling in 2023 (Fig. 2g). The five samples from Kaya was combined to form a single composite sample representing the Kaya trial fields, and the four samples from Ishikawa were combined to represent the Ishikawa trial fields (Fig. 2h). Two subsamples of 15 g each were extracted from each of the two representative samples. One subsample was mixed with 0.2 g of Mamekko fertilizer (fertilizer treatment), while the other subsample underwent the incubation treatment without fertilizer mixture (soil treatment). Each subsample was placed in a 15 ml centrifuge tube and flooded with distilled water to maintain a 0.01 m water layer above the soil surface throughout the experiment, with water levels adjusted as needed. Each centrifuge tube was wrapped with a food-grade plastic film with a small hole that allows generated gas to escape while preventing excessive evaporation. For one-time measurement of mineral nitrogen, one set of four centrifuge tubes (2 villages × 2 treatments) was placed in an incubator adjusted at 15 °C, while the other set was placed at 30 °C. NH4-N and NO3-N concentrations in the soil were measured at ten time points (0, 4, 7, 10, 14, 18, 24, 31, 40, and 50 days after the onset of incubation) as described above. The sum of NH4-N and NO3-N was regarded as the amount of mineral nitrogen present in the soil at the time of measurement. In total, 80 centrifuge tubes (2 villages × 2 treatments × 2 temperatures × 10 measurements) were prepared.

Estimation of decomposition rate

The decomposition of organic matter in soil can be explained as a first-order reaction, as follows19,20,21,22,23:

where Corg-N is the amount of decomposable organic N, Cmin-N is the amount of mineral N produced from organic N, and k is the rate constant. Mineral nitrogen was assumed to originate from soil organic matter (Corg-soil-N) and from Mamekko fertilizer (Corg-fert-N). Therefore, two rate constants (ksoil for soil organic matter; kfert for Mamekko fertilizer) were estimated as follows:

where t is the elapsed time (day). For initial values in Eq. (3), available nitrogen (potentially mineralizable nitrogen from soil) was used as \({C}_{org-soil-{\text{N}}}^{t=0}\) for soil, while \({C}_{org-fert\text{-N}}^{t=0}\) was set at 50 mg 100 g−1 for Mamekko fertilizer based on the assumed decomposable nitrogen during the incubation period. The \({C}_{org-soil-{\text{N}}}^{t=0}\) values were 16.76 mg 100 g−1 and 25.375 mg 100 g−1 for Kaya and Ishikawa, respectively, obtained by averaging available nitrogen values across the fields in each location. The rate constant k for each treatment at each temperature was obtained by fitting Eq. (3) to the measured values.

Soil pH is known to converge between 6.7 and 7.0 several days to a few weeks after the onset of submergence24. A preliminary experiment confirmed the process in which soil pH of both Kaya and Ishikawa soils, with or without Mamekko fertilizer, converged between 6.5 and 7.0, 10 to 15 days after the onset of submergence (Supplementary Fig. 3). Because the fluctuation of soil pH greatly affects soil microbial activity, early measurements were excluded from the fitting, ranging from 0 to 10 days after the onset of incubation.

Soil microbiome analysis

Microbiomes and functional analysis

The microbiome analysis was performed using the five subsamples from Kaya and four subsamples from Ishikawa (Fig. 2g), each weighing approximately 400 mg, which were extracted before the incubation experiment as described above. DNA was extracted using the NucleoSpin® Soil kit (MACHEREY–NAGEL, Düren, Germany), and the 16S rRNA V4 region from the extracted DNA was amplified by PCR using the mix primers, including the Illumina sequencing adapter underlined below25;

ACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTCTTCCGATCTNNNNNGTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA,

And

GTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGTGCTCTTCCGATCTNNNNNGGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT.

The PCR products were then purified using VAHTS DNA Clean Beads (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Library preparation and sequencing were performed using the MiSeq Reagent Kit v3 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with a sequencing length of 2 × 300 bp.

For data analysis, only sequences including primer sequences were selected using the fastx barcode splitter of the FASTX-Toolkit ver. 0.0.14. Primer sequences were trimmed using the FASTX-Toolkit Fastx trimmer. Low-quality sequences (quality value less than 20) and sequences shorter than 130 bases, along with their pair sequences, were removed using Sickle ver. 1.33. FLASH ver. 1.2.11 was used to merge reads with at least a 10-base overlap. Further processing involved the elimination of chimeric and noisy sequences using the dada2 plugin in Qiime2 ver. 2023.526,27. The outcome comprised representative sequences and an amplicon sequence variant (ASV) table. Phylogenetic analysis used these ASV representatives, and taxonomic assignment was performed with the Greengenes ver 13_8 reference database (97% OTU) via the feature classifier, alignment, and phylogeny plugins28. Diversity analysis was conducted using Qiime2’s diversity plugin.

Functional composition tables based on METACYC and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) orthologs were generated using the representative sequences from Qiime2, with phylogenetic investigation of communities by reconstruction of unobserved states 2 (PICRUSt2) ver. 2.4.1 (Douglas et al. 2020). The functional composition tables based on METACYC was statistically analyzed using STAMP ver. 2.1.329. Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) ver. 1.0.8 was employed to determine significant differences in the relative abundance of strains between groups30.

Results

On-farm trial

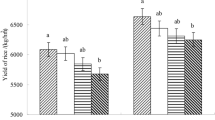

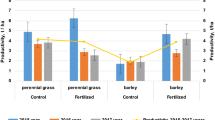

Due to constraints of conducting this study in commercial farmers’ fields, we assigned one fertilizer treatment level per field, establishing six fields each in Kaya and Ishikawa over a two-year period, rather than dividing fields into six plots with replications in each village. Plant growth indicators were analyzed using a generalized linear mixed model with fertilizer and year as fixed effects, and fields nested within villages as random effects (Fig. 3, Table 4, and Supplementary Table 2).

The model’s explanatory power (conditional R2) was 74.0%, 68.5%, and 68.0% for nitrogen content, dry matter weight, and brown rice yield, respectively. Fixed effects (marginal R2) accounted for 64.3%, 44.5%, and 34.4% of variance, with random effects contributing the remaining 9.7%, 24.0%, and 33.6%. For nitrogen content, variation at village and field levels was nearly equal (33.85 and 33.56), whereas within-village field variation exceeded village-level variation for dry matter weight (0.17 and 0.56) and yield (0.17 and 0.24). BLUPs showed that nitrogen content, dry matter weight, and yield were higher in Ishikawa than Kaya by 6.98 kg ha⁻1, 0.44 t ha⁻1, and 0.5 t ha⁻1, respectively, with this effect being most pronounced for nitrogen content.

Fertilizer treatment analysis revealed significant increases in nitrogen content, dry matter weight, and brown rice yield in the 2–0 treatment compared to 0–0. The 2–1 treatment significantly increased nitrogen content and dry matter weight but not yield. Other treatments (1–0, 1–1, 3–0) showed no significant increases in measured indicators.

The 2–0 fertilization likely improved nitrogen supply throughout growth periods, significantly increasing panicle number and spikelets per unit area. This yield increase resulted from enhanced nitrogen supply during vegetative growth that increased panicle numbers, while maintaining sufficient nutrition during reproductive growth to prevent reduced grain filling. The 2–1 treatment, despite matching 2–0 until panicle initiation, failed to significantly increase yield. Although it increased tiller numbers, these did not translate to more panicles, suggesting the additional application may have inhibited panicle development. In the 3–0 treatment, excessive basal fertilization likely inhibited vegetative growth, as neither tiller nor panicle numbers increased. However, spikelets per panicle showed an increasing trend, suggesting remaining fertilizer may have compensatorily promoted spikelet formation.

All measured indicators increased significantly in 2021 compared to 2020. While tiller numbers decreased, spikelets per panicle, spikelets per unit area, and notably 1000-grain weight increased significantly. This suggests 2021’s meteorological conditions suppressed vegetative growth but enhanced reproductive growth and grain filling, ultimately increasing yields.

Soil incubation experiment

Soil solution pH monitoring revealed distinct patterns during incubation (Supplementary Fig. 3). Due to significant pH fluctuations in the first 10 days, particularly pronounced in fertilizer treatments, these early measurements were excluded from the mineralization rate analysis.

Temperature and location significantly influenced nitrogen mineralization patterns (Fig. 4). Without fertilizer addition, mineralization rate constants (k) increased with temperature in both locations, with values rising from 0.0067 to 0.034 day−1 in Kaya and 0.011 to 0.038 day−1 in Ishikawa soils. Ishikawa soils consistently showed higher rate constants than Kaya soils at both temperatures. This difference, combined with higher initial available nitrogen content in Ishikawa soils (16.76 vs 25.375 mg 100 g−1) resulted in greater total mineralized nitrogen in Ishikawa (15 °C: 16 mg; 30 °C: 23 mg) compared to Kaya (15 °C: 10 mg; 30 °C: 15 mg).

Nitrogen mineralized during 50-day period incubated at 15 (blue) and 30 °C (red). (a) Nitrogen mineralized from soils of Kaya on-farm trial fields. (b) Nitrogen mineralized from soils of Ishikawa on-farm trial fields. (c) Nitrogen mineralized from soils of Kaya on-farm trial fields mixed with Mamekko fertilizer. (d) Nitrogen mineralized from soils of Ishikawa on-farm trial fields mixed with Mamekko fertilizer. Each circle represents a measured value at the respective temperature. Dotted lines represent estimated values fitting to a first order reaction model, with rate constant k shown for each line. Values measured during the period between 0 and 10 days of incubation were excluded from the fitting due to significant changes in soil solution pH (see Supplementary Fig. 3).

The response to fertilizer addition varied markedly between locations. In Ishikawa soils, fertilizer addition enhanced total mineralized nitrogen (15 °C: 16 mg; 30 °C: 31 mg) compared to unfertilized treatments. This enhancement was associated with measurable mineralization rate constants for Mamekko fertilizer (15 °C: 0.0012 day−1; 30 °C: 0.009 day−1). In contrast, Kaya soils showed minimal response to fertilizer addition (15 °C: 8 mg; 30 °C: 17 mg), with mineralization rate constants for Mamekko fertilizer approaching zero at both temperatures (15 °C: 0.000 day−1; 30 °C: 0.000 day−1).

The net contribution of fertilizer to nitrogen mineralization, calculated as the difference between fertilized and unfertilized treatments, showed contrasting patterns between locations. Ishikawa soils exhibited positive fertilizer contributions, particularly at 30 °C (8 mg), while maintaining neutral effects at 15 °C (0 mg). In contrast, Kaya soils showed negative contributions at 15 °C (− 2 mg) and minimal positive effects at 30 °C (2 mg), suggesting potential nitrogen immobilization or denitrification losses at lower temperatures. Despite these differences, soil-derived nitrogen mineralization remained the dominant source of mineral nitrogen at both locations and temperatures.

The incubation experiments revealed distinct differences in nitrogen mineralization patterns between the two locations. Ishikawa soils showed consistently higher mineralization potential, with net nitrogen contributions from fertilizer ranging from 0 to 8 mg depending on temperature. In contrast, Kaya soils exhibited limited nitrogen mineralization, with net contributions ranging from -2 to 2 mg. The negative values observed in Kaya soils at lower temperatures coincided with near-zero mineralization rate constants for the added fertilizer.

Soil microbiome analysis

The microbiome analysis of soil samples from Kaya and Ishikawa revealed significant differences in microbial community composition and functional potential, providing insights into the contrasting nitrogen dynamics observed in the field trials and incubation experiments.

Microbial community composition and diversity

16S rRNA V4 region sequencing generated 68,000–92,000 pair-reads per sample, identifying a total of 6,607 Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) (Supplementary Table 3). Principal coordinate analysis using weighted unifrac distance highlighted distinct microbial communities in Ishikawa and Kaya soils (Supplementary Fig. 4). Alpha diversity analysis revealed that Ishikawa soil had significantly lower microbial diversity compared to Kaya soil, as indicated by lower values of observed ASVs, Chao1 index, Shannon index, and Pielou’s evenness (Supplementary Table 4, p < 0.05 for observed ASVs and Chao1 index and p < 0.001 for Shannon index and Pielou’s evenness). At the kingdom level, bacteria predominated in both soil types, with archaea comprising less than 5% of the microbiome (Supplementary Table 5). Major bacterial phyla included Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Chloroflexi, and Planctomycetes. LEfSe analysis revealed that the population of Proteobacteria (p < 0.01) was larger in Ishikawa soil, while Actinobacteria (p < 0.001) and Verrucomicrobia (p < 0.05) were more abundant in Kaya soil (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). At the genus level, 678 ASVs were detected, with significant differences observed in 47 and 106 ASVs for Ishikawa and Kaya soil microbiomes, respectively (Fig. 5b, Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Tables 7 and 8).

Microbiomes from paddy soils in Kaya and Ishikawa villages. Relative frequencies of soil microbiomes are presented at (a) phylum level with top 16 amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) in legends, and (b) genus level with top 16 ASVs in legends. In each legend, the most specific taxonomic names that could be assigned to the ASVs are shown (see Supplementary Tables 6 and 7 for complete taxonomic information).

Functional potential

PICRUSt2 analysis based on METACYC and KEGG orthologs revealed significant differences in the predicted functional potential of the microbial communities between Kaya and Ishikawa soils, particularly in pathways related to nitrogen metabolism (Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Tables 9 and 10). Principal coordinate analysis further demonstrated the differentiated functional aspects of the microbiomes in Ishikawa and Kaya soils (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Denitrification pathways

Ishikawa soil showed significantly lower relative frequencies of genes involved in denitrification compared to Kaya soil (Fig. 6 and Table 5). Specifically, genes encoding nitrate reductase (narG, narH, narI; K00370, K00371, K00374), nitrite reductase (nirK; K00368), nitric oxide reductase (norB; K04561), and nitrous oxide reductase (nosZ; K00376) were all less abundant in Ishikawa soil (p < 0.001 for narG, narH, and narI, and p < 0.05 for nirK, norB, and nosZ). These results suggest a lower potential for denitrification in Ishikawa soil, which could contribute to greater nitrogen retention.

Nitrogen metabolism pathway generated by the KEGG PATHWAY database. PICRUSt2 analysis of soil microbiomes from paddy soils in Kaya and Ishikawa villages revealed higher relative frequencies of some denitrification pathways in Kaya, highlighted in red (see Table 5 for detailed results).

Urea cycle and arginine biosynthesis

Genes involved in the urea cycle and arginine biosynthesis were also less abundant in Ishikawa soil compared to Kaya soil (Fig. 7, Table 5). Notably, genes encoding argininosuccinate synthase (argG; K01940), argininosuccinate lyase (argH; K01755), and arginase (rocF; K01476) showed significantly lower relative frequencies in Ishikawa soil (p < 0.05 for argG and argH, and p < 0.01 for rocF). This suggests a lower potential for organic nitrogen assimilation and turnover in the microbial community of Ishikawa soil.

Arginine biosynthesis pathway generated by KEGG PATHWAY database. PICRUSt2 analysis of soil microbiomes from paddy soils in Kaya and Ishikawa villages revealed higher relative frequencies of some urea cycle pathways in Kaya, highlighted in red (see Table 5 for detailed results).

Nitrification potential

Although less pronounced, there were also differences in the abundance of genes related to nitrification. Ishikawa soil showed slightly lower relative frequencies of genes encoding hydroxylamine dehydrogenase (hao; K10535) compared to Kaya soil (Supplementary Fig. 8, p < 0.1), suggesting a potentially lower nitrification capacity in Ishikawa soil. No significant differences were found in nitrogen fixation and nitrate reduction pathways between the two soil types. In total, 1,056 ASVs related to these KEGG orthologs were found to be less prevalent in the Ishikawa soil microbiomes (Supplementary Table 11). These differences in microbial community composition and functional potential align with the observations from the field trials and incubation experiments. The lower abundance of denitrification and urea cycle genes in Ishikawa soil may explain the higher inorganic nitrogen availability and stronger response to organic fertilizer application observed in the field. Conversely, the higher abundance of these genes in Kaya soil may contribute to greater nitrogen losses and reduced plant nitrogen uptake, resulting in the weaker response to organic fertilizer application observed in the field trials.

Overall, the soil microbiome analysis provides a mechanistic explanation for the observed differences in nitrogen dynamics between Kaya and Ishikawa soils, highlighting the crucial role of soil microbial communities in mediating the effectiveness of organic fertilizer application in rice cultivation.

Discussion

Nitrogen mineralization from organic fertilizer is greatly affected by moisture content and temperature of surrounding soils. Because soils are normally kept saturated throughout the growth period in rice production, nitrogen mineralization from organic fertilizer is mainly regulated by soil temperature in paddy soils. Climatic condition is relatively homogeneous within a local rice farming community, and little variation of soil temperature is expected among rice fields. Therefore, the same dose and timing of fertilizer application has been recommended regardless of organic or inorganic fertilizer for a local rice farming community31. However, the two-year on-farm trials in the present study revealed notable differences in plant growth indicators between the two villages, as evidenced by the variance components and BLUPs of the random effects in our mixed model (Table 4). Even though an interaction between fertilizer treatment and location was not tested directly, the analysis clearly showed higher values of nitrogen content, dry matter weight, and brown rice yield in Ishikawa compared to Kaya. This location effect was particularly pronounced for nitrogen content, suggesting that local soil conditions in Ishikawa may facilitate greater nitrogen availability from organic fertilizers. While traditional fertilizer recommendations assume homogeneous responses within a farming community31, our findings indicate substantial spatial heterogeneity in plant responses to the same fertilizer treatments. This highlights the need to consider location-specific factors when developing fertilizer management strategies, even within seemingly homogeneous farming communities.

The incubation experiments provided mechanistic insights into the contrasting field responses to organic fertilizer application between the two locations (Fig. 4). The key difference lay in the temperature-dependent nitrogen mineralization patterns and their response to fertilizer addition. Ishikawa soils exhibited efficient nitrogen mineralization from organic fertilizer, particularly at higher temperatures (30 °C: 8 mg net contribution), with measurable mineralization rate constants (0.0012 day−1 at 15 °C; 0.009 day−1 at 30 °C). This positive response aligns with the higher yield observed in Ishikawa field trials (Fig. 3 and Table 4). In contrast, Kaya soils showed either negligible or negative responses to fertilizer addition (-2 to 2 mg net contribution), with mineralization rate constants approaching zero at both temperatures. This suppression of fertilizer nitrogen mineralization in Kaya soils suggests active nitrogen immobilization by soil microbes or potential losses through denitrification, consistent with the lower yield observed in Kaya field trials (Fig. 3 and Table 4). These location-specific differences in nitrogen mineralization patterns highlight how local soil characteristics can fundamentally alter organic fertilizer efficiency. These findings provide a quantitative basis for site-specific organic fertilizer management. The temperature-dependent mineralization patterns suggest that both timing and rate of fertilizer application should be optimized according to local soil characteristics, particularly in soils showing minimal mineralization response.

The microbiome analysis provided direct evidence for the differences in composition and function of soil microbes between the two locations. Ishikawa soil was characterized as having significantly lower relative frequencies of genes involved in denitrification compared to Kaya soil (Table 5). Specifically, genes encoding nitrate reductase (narG, narH, narI), nitrite reductase (nirK), nitric oxide reductase (norB), and nitrous oxide reductase (nosZ) were all less abundant in Ishikawa soil (Fig. 6 and Table 5). Additionally, genes involved in the urea cycle and arginine biosynthesis were also less abundant in Ishikawa soil (Fig. 7 and Table 5). These differences in microbial community composition and functional potential align with the observations from the field trials (Fig. 3 and Table 4) and incubation experiments (Fig. 4).

The observed differences in soil microbial communities between Kaya and Ishikawa may be attributed to the differences in the location and topography of the fields. The fields in Kaya are situated at the foot of slopes in a valley bottom where several rivers converge (Fig. 1), an environment that is conducive to the movement and accumulation of water and organic matter from upper slopes. Such environmental conditions have been suggested to promote the increase of denitrifying bacteria and the enhancement of denitrification enzyme activity6,10,11. Moreover, the high soil moisture content maintained at the foot of slopes may facilitate the anaerobic decomposition of organic matter, leading to the dominance of denitrifying and organic matter-immobilizing microorganisms5,8,32. In contrast, the fields in Ishikawa are located on a valley floor developed on a floodplain of a river, where good drainage and low accumulation of organic matter are expected31. These environmental conditions may promote aerobic decomposition of organic matter and favor nitrification while suppressing the proliferation of denitrifying bacteria6,10,33. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have reported the influence of topography on soil microbial communities and nitrogen cycling in various agroecosystems6,10,18. However, while most of these studies focused on upland soils, our study demonstrates that similar topographic effects can also be observed in paddy soils, as indicated by the differences in nitrogen mineralization rates (Fig. 4) and soil microbial communities (Figs. 5, 6, 7 and Table 5) between the Ishikawa and Kaya villages. Furthermore, our study extends the understanding of topographic effects on soil microbes by investigating the interaction with organic fertilizer application, which has not been thoroughly examined in previous studies.

The findings of this study have significant implications for the management of organic fertilizers in rice production, particularly in regions with varied topography. Our results suggest that the effectiveness of organic fertilizers can vary significantly within a relatively small geographic area due to differences in soil microbial communities and nitrogen cycling processes (Figs. 5, 6, 7 and Table 5), which are strongly influenced by topographic factors such as slope position9,10,11. In the context of organic rice farming, these findings highlight the need for site-specific management strategies that take into account the local topographic conditions and their potential impact on soil microbial communities and nitrogen dynamics12,13,15. For example, in fields located at the foot of slopes, where denitrification and organic matter immobilization are more likely to occur, higher rates of organic fertilizer application may be necessary to compensate for the potential nitrogen losses. Alternatively, the use of organic amendments with lower C/N ratios or the application of nitrification inhibitors could help to reduce nitrogen losses and improve the efficiency of organic fertilizers in these locations1,34. On the other hand, in fields located on valley floors or in areas with better drainage and lower accumulation of organic matter, lower rates of organic fertilizer application may be sufficient to meet the nitrogen requirements of the rice crop, as the potential for nitrogen losses through denitrification and immobilization is lower in these locations. In such cases, the use of organic fertilizers with higher C/N ratios could help to synchronize nitrogen release with crop demand and minimize the risk of nitrogen losses.

The results of the on-farm trials revealed that the effectiveness of organic fertilizers was dependent on the application rate, with the 2–0 treatment (2 t ha−1 of Mamekko fertilizer applied as basal fertilizer) showing the most substantial increases across all measured variables (Fig. 3 and Table 4). This treatment, which supplied 80–84 kg N ha−1, may provide a benchmark for the appropriate nitrogen application rate in organic rice cultivation in this region. The 2–0 fertilization likely increased nitrogen supply to the plant throughout both vegetative and reproductive growth periods, resulting in improved dry matter production capacity. Our yield component analysis demonstrated that this treatment significantly increased the number of panicles and spikelets per unit area (Supplementary Table 2). The significant yield increase in the 2–0 treatment can therefore be attributed to enhanced nitrogen supply during the vegetative growth period that promoted tiller and panicle formation, while maintaining sufficient nutrition into the reproductive period that prevented reduction in grain filling. This observation is consistent with the well-established understanding that a certain level of nitrogen fertilizer application is necessary for the manifestation of fertilizer effects, regardless of the type of fertilizer used (chemical or organic)34,35,36. Interestingly, the 2–1 treatment, which received the same basal application as 2–0 plus additional fertilizer at panicle initiation, did not result in significant yield increases despite showing significant increases in nitrogen uptake and biomass. Although this treatment increased tiller numbers, these did not translate into increased panicle numbers, suggesting that the additional fertilization may have inhibited panicle development. Similarly, the 3–0 treatment with higher basal application showed no significant improvements, likely because excessive basal fertilization inhibited vegetative growth, as evidenced by the lack of increase in tiller and panicle numbers. These findings highlight the importance of not only the total amount but also the timing of organic fertilizer application for maximizing rice productivity.

Overall, this study underscores the importance of considering topographic factors and their influence on soil microbial communities and nitrogen cycling when developing organic fertilizer management strategies for rice production. By adopting site-specific approaches that take into account the local topographic conditions, organic rice farmers may be able to optimize the use of organic fertilizers, improve nitrogen use efficiency, and reduce the environmental impacts associated with nitrogen losses2,35,37. This, in turn, could contribute to the development of more sustainable and resilient organic rice farming systems, particularly in regions with varied topography1,38,39. Future research could focus on developing more precise mapping techniques to identify areas with different microbial community compositions within rice farming regions, potentially leading to more targeted and efficient fertilizer application strategies. Additionally, investigating the long-term effects of these site-specific organic fertilizer management practices on soil health, crop productivity, and environmental sustainability would provide valuable insights for the continued development of sustainable organic rice farming systems. Moreover, the findings of this study also have broader implications for the management of organic fertilizers in other cropping systems and agroecosystems. While the specific topographic factors and their influence on soil microbial communities and nitrogen cycling may vary depending on the local context, the general principles of site-specific management based on an understanding of the underlying ecological processes are likely to be applicable across a range of cropping systems and environments5,40,41. As such, the insights gained from this study could inform the development of more effective and sustainable organic fertilizer management strategies in a variety of agricultural contexts.

Conclusion

This study suggests that topographic variation may influence organic fertilizer effectiveness in rice cultivation through its effects on soil microbial communities. Valley floor fields showed higher grain yields with organic fertilizer application, compared to footslope fields, probably due to distinct patterns of nitrogen mineralization between locations. Microbiome analysis revealed that these differences are linked to lower abundance of denitrification and ammonia assimilation genes in valley floor soils, resulting in more efficient nitrogen retention and availability to plants. These findings suggest that organic fertilizer management strategies should be tailored to local topographic conditions for optimal results. The study highlights the importance of understanding the relationship between topography, soil microbial communities, and nitrogen cycling for developing more efficient organic rice farming practices. Future research could focus on developing practical tools for predicting microbial community variations across rice-growing landscapes to help optimize site-specific organic fertilizer management strategies.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as they are part of an ongoing research project pending final quality assessment and documentation, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Choudhury, A. T. M. A. & Kennedy, I. R. Nitrogen fertilizer losses from rice soils and control of environmental pollution problems. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 36, 1625–1639 (2005).

Reganold, J. P. & Wachter, J. M. Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nat. Plants 2, 15221 (2016).

Dobermann, A., Sta Cruz, P. C. & Cassman, K. G. Fertilizer Inputs, Nutrient Balance, and Soil Nutrient-Supplying Power in Intensive, Irrigated Rice Systems. I. Potassium Uptake and K Balance. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems 46 (1996).

Ishii, S., Ikeda, S., Minamisawa, K. & Senoo, K. Nitrogen cycling in rice paddy environments: Past achievements and future challenges. Microbes Environ. 26, 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1264/jsme2.ME11293 (2011).

Blagodatskaya, E. & Kuzyakov, Y. Mechanisms of real and apparent priming effects and their dependence on soil microbial biomass and community structure: Critical review. Biol. Fertil. Soils 45, 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-008-0334-y (2008).

Florinsky, I. V., McMahon, S. & Burton, D. L. Topographic control of soil microbial activity: A case study of denitrifiers. Geoderma 119, 33–53 (2004).

Frindte, K., Pape, R., Werner, K., Löffler, J. & Knief, C. Temperature and soil moisture control microbial community composition in an arctic–alpine ecosystem along elevational and micro-topographic gradients. ISME J. 13, 2031–2043 (2019).

Liu, Y., Du, J., Xu, X., Kardol, P. & Hu, D. Microtopography-induced ecohydrological effects alter plant community structure. Geoderma 362, 114119 (2020).

Ashiq, W. et al. Interactive role of topography and best management practices on N2O emissions from agricultural landscape. Soil Tillage Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2021.105063 (2021).

Johnson, F. E., Lerch, R. N., Motavalli, P. P., Veum, K. S. & Scharf, P. C. Spatial variability of denitrification enzyme activity and actual denitrification emissions on Missouri claypan soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 86, 1582–1596 (2022).

Pennock, D. J., van Kessel, C., Farrell, R. E. & Sutherland, R. A. Landscape-scale variations in denitrification. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 56, 770–776 (1992).

Brouwer, J. & Powell, J. M. Increasing nutrient use effciency in West-African agriculture: The impact of micro-topography on nutrient leaching from cattle and sheep manure. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 71, 229–239 (1998).

Suriyavirun, N., Krichels, A. H., Kent, A. D. & Yang, W. H. Microtopographic differences in soil properties and microbial community composition at the field scale. Soil Biol. Biochem. 131, 71–80 (2019).

Watts, D. B., Torbert, H. A. & Prior, S. A. Soil property and landscape position effects on seasonal nitrogen mineralization of composted dairy manure. Soil Sci. 175, 27–35 (2010).

Senthilkumar, S., Basso, B., Kravchenko, A. N. & Robertson, G. P. Contemporary evidence of soil carbon loss in the U.S. corn belt. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 73, 2078–2086 (2009).

Tiwari, M. B., Tiwari, B. K. & Mishra, R. R. Biology and fertility o soils enzyme activity and carbon dioxide evolution from upland and wetland rice soils under three agricultural practices in hilly regions. Biol Fertil. Soils 7, 10095 (1989).

Boling, A. A. et al. The effect of toposequence position on soil properties, hydrology, and yield of rainfed lowland rice in Southeast Asia. Field Crops Res. 106, 22–33 (2008).

Sekiya, N. et al. Sustainable nitrogen management in rice farming: spatial patterns of nitrogen availability and implications for community-level practices. Sustainability 16, 9880 (2024).

Stanford, G. & Smith, S. J. Nitrogen Mineralization Potentials of Soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 36, 465–472 (1972).

Nuske, A. & Richter, J. N-mineralization in Loss-Parabrownearthes: Incubation experiments. Plant Soil 59, 237–247 (1981).

Campbell, C. A., Jame, Y. W. & Winkleman, G. E. Mineralization rate constants and their use for estimating nitrogen mineralization in some Canadian prairies soils. Can. J. Soil Sci. 64, 333–343 (1984).

Tan, X., Shao, D., Gu, W. & Liu, H. Field analysis of water and nitrogen fate in lowland paddy fields under different water managements using HYDRUS-1D. Agric. Water Manag. 150, 67–80 (2015).

Gulati, D., Satpute, S., Kaur, S. & Aggarwal, R. Estimation of potential recharge through direct seeded and transplanted rice fields in semi-arid regions of Punjab using HYDRUS-1D. Paddy Water Environ. 20, 79–92 (2022).

Ponnamperuma, F. N., Martinez, E. & Loy, T. Influence of redox potential and partial pressure of carbon dioxide on pH values and the suspension effect of flooded soils. Soil Sci. 101, 421–431 (1966).

Apprill, A., Mcnally, S., Parsons, R. & Weber, L. Minor revision to V4 region SSU rRNA 806R gene primer greatly increases detection of SAR11 bacterioplankton. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 75, 129–137 (2015).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 13, 581–583 (2016).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019).

DeSantis, T. Z. et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 5069–5072 (2006).

Parks, D. H., Tyson, G. W., Hugenholtz, P. & Beiko, R. G. STAMP: Statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics 30, 3123–3124 (2014).

Segata, N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12, 60 (2011).

Sekiya, N. et al. Shoot and root responses of rice plants to belowground environmental heterogeneity within a local rice farming community. Discov. Agric. 2, 118 (2024).

Odu, C. T. I. & Adeoye, K. B. Heterotrophic nitrification in soils: A preliminary investigation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2, 41–45 (1970).

Peng, X., Horn, R. & Smucker, A. Pore shrinkage dependency of inorganic and organic soils on wetting and drying cycles. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 71, 1095–1104 (2007).

Mulvaney, R. L., Khan, S. A. & Ellsworth, T. R. Synthetic nitrogen fertilizers deplete soil nitrogen: A global dilemma for sustainable cereal production. J. Environ. Qual. 38, 2295–2314 (2009).

Seufert, V., Ramankutty, N. & Foley, J. A. Comparing the yields of organic and conventional agriculture. Nature 485, 229–232. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11069 (2012).

Nobuhito Sekiya, Akira Asano, Mchuno Alfred Peter, Emily Waringa Gichuhi, Daniel Makori Menge, Mayumi Kikuta, Makoto Kondo, Daigo Makihara. Effects of nitrogen application in upland rice cultivars: Balancing sink-source relationships for sustainable yield in water-limited environments. Field Crops Research332, 110012,ISSN 0378-4290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2025.110012 (2025).

Timsina, J. & Connor, D. J. Productivity and management of rice±wheat cropping systems: Issues and challenges. Fiels Crops Res. 69, 93–132 (2001).

Pingali, P. L. Green revolution: Impacts, limits, and the path ahead. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 12302–12308. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0912953109 (2012).

Peng, S. et al. Strategies for overcoming low agronomic nitrogen use efficiency in irrigated rice systems in China. Field Crops Res. 96, 37–47 (2006).

Tilman, D., Cassman, K. G., Matson, P. A., Naylor, R. & Polasky, S. Agricultural sustainability and intensive production practices. Nature 418, 671–677 (2002).

Walters, D. R. & Bingham, I. J. Influence of nutrition on disease development caused by fungal pathogens: Implications for plant disease control. Ann. Appl. Biol. 151, 307–324 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Yosano municipal government. We are grateful to K. Miyamoto, Y. Odani, K. Ohta and T. Ohe for their work in the rice production and K. Tanaka and T. Araki for their help in the data acquisition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: N.S., S.I., and K.W. Methodology: N.S., S.I., and K.W. Formal analysis and investigation: A.Ma, A.Mu, M.P., M.G., H.K. Writing – original draft preparation: A.Ma and N.S. Writing – review and editing: A.Ma, A.Mu, M.P., M.G., H.K., S.I., and K.W. Funding acquisition: N.S. Resources: N.S., S.I., and K.W. Supervision: N.S., S.I., and K.W.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sekiya, N., Mae, A., Murai, A. et al. Soil microbes and organic fertilizer efficiency are associated with rice field topography. Sci Rep 15, 24939 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09111-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09111-x