Abstract

Large-scale studies that investigate longitudinal changes in SARS-CoV-2 antibody reactivity in newborn infants are limited. Infants acquire maternal IgG antibodies that decay after birth; if infected, they produce infant-derived IgG, IgA, and IgM antibodies. The New York State Newborn Screening Program (NYS NSP) collects dried blood spots (DBS) from infants at birth and follow-up specimens from a select group of infants, many of whom are premature. We tested 100,318 remnant DBS from 50,036 infants with repeat specimens received between November 2019 and November 2021 for SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies; 9611 infants were IgG reactive at birth and 630 seroconverted for SARS-CoV-2 IgG. The first infant seroconversion occurred in March 2020. Infants antibody-reactive at birth were less likely to have low or very low birthweight or be from a multiple birth; infants with repeat specimens were less likely to be reactive at birth than those with single specimens. Antibody decay occurred in a non-linear process with initial rapid decay followed by slower decay (half-life of 22–23 days for 0–30 days after birth, 37–38 days for > 30 days after birth). Seroconversion was confirmed by retesting IgG seroconverting infants for detectable IgA and IgM SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies specific to SARS-CoV-2 develop within 1–2 weeks after infection or vaccination and are useful markers to determine exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination1,2. Pregnant individuals provide the infant with passive immunity through transplacental transfer, a time-elapsed process that occurs between maternal IgG antibody development and birth3. Dried blood spots (DBS) have been validated as an alternative to serum for measurement of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies against nucleocapsid (N) and spike (S) proteins 4,5,6,7,8,9,10. DBS are collected by heel stick from every infant born in New York State (NYS) and submitted to the NYS Newborn Screening Program (NSP) to test for 50 + disorders. In a previous cross-sectional study, we analyzed SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in NSP DBS collected at birth (median age 1 day) from 415,293 infants in NYS over a 2 year period and determined that IgG seroprevalence in infants reflected statewide fluctuations in COVID-19 infections and vaccinations among reproductive-aged females11.

While serosurveys using infant DBS are useful to monitor antibody dynamics in a population of individuals recently giving birth, large scale studies of the SARS-CoV-2 antibody response in infants using sequential collections, which allow for the study of antibody seroconversion and decay, are lacking12,13,14,15. The NYS NSP program requests repeat DBS from certain infants, including those in the neonatal intensive care unit, those with borderline test results, and those with suboptimal or unsatisfactory specimens. In our previous large-scale SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence study of infant DBS, we tested repeat samples collected from individual babies, but excluded them from the analysis to allow for the determination of population seroprevalence11. In this study, we evaluated longitudinal SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody data from 50,036 infants with repeat DBS collected in NYS between November 2019 and November 2021. We used a multiplex SARS-CoV-2 immunoglobulin microsphere immunoassay (MIA) that has been validated for DBS9 to analyze patterns of antibody reactivity to N and S antigens in infants over time. We investigated longitudinal changes in infants that were reactive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies at birth and sought to identify associations between SARS-CoV-2 antibody reactivity and demographic characteristics. We also characterized the decay rate and longevity of passively acquired antibodies using linear mixed effects models. IgG detected in infants at birth is suggestive of maternal derived (passive) immunity, while IgG, IgM, and IgA reactivity acquired post-birth is indicative of perinatal or neonatal (active) immunity12,16,17,18. Finally, we documented IgG antibody seroconversion in infants following presumed infection with SARS-CoV-2 and confirmed seroconversion in a select group of infants by detecting SARS-CoV-2 N and S IgA and IgM.

Methods

Specimens

Specimens for this longitudinal study were dried blood spots (DBS) submitted to the NYS NSP from infants born from November 1, 2019 through November 30, 2021. Infants either had a single DBS, two DBS, or more than two DBS submitted during this period with enough sample available for antibody testing. In NYS, repeat newborn screening DBS are requested from infants if the initial specimen is collected less than 24 h from birth, has borderline results, or is sub-optimal or unsuitable for testing. Repeat specimens are also requested if the infant is transferred to the NICU or receives total parenteral nutrition at the time of initial specimen collection. DBS punches, 3.2 mm in diameter, were collected into 96-well plates, blinded as previously described, and stored at − 20 °C in sealed plastic bags with desiccant until tested for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies11. A linking ID was assigned to samples from the same infant to identify repeat specimens.

Assay procedure

SARS-CoV-2 Spike subunit S1 (S) (Sino Biological, Wayne, PA) and Nucleocapsid (N) (Native Antigen, Oxford, UK) antigens were coupled to MagPlex-C microspheres (i.e. beads, Luminex Corp., Austin, TX). SARS-CoV-2 IgG MIA was performed as previously described9,11. SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgA MIAs were performed as described for the SARS-CoV-2 IgG MIA, except that IgM- and IgA-specific secondary antibodies (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL) and IgM and IgA specific positive controls were used. Samples were analyzed using a FlexMap 3D instrument (Luminex Corp., Austin, TX) which produces a Median Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) for each antigen-coupled bead set. 173 negative DBS were tested to set cutoffs for each bead lot. Results that were less than the mean MFI + 6 standard deviations (SD) were classified as nonreactive, and greater than the mean MFI + 6 SDs were considered reactive. Multiple lots of beads were used for this study, and an average of the N lot cutoffs and S lot cutoffs was applied to all samples to determine reactivity. MFI Index was calculated for each bead by dividing the MFI value by the average reactive cutoff value; values of > 1.0 (0.0 on a natural logarithmic scale) indicated a reactive result for that bead set.

Demographic analyses

This study included data submitted by the birth hospital (newborn birthweight, gestational age, birth date, plurality status, transfusion status, DBS collection date, birth hospital, and maternal birth date) and antibody test data (reactivity and MFI for S and N). Infants with more than one specimen collected were included if their initial sample was collected within 4 days of birth and they had one or more repeat samples collected within the testing period of November 2019 through November 2021. As a comparison group, infants with a single specimen collected were included in the study if specimens were collected < 30 days after birth within the testing period. Infants were excluded from the study if their parents opted out of public health research, if they received transfusions prior to collection, or if they resided outside of NYS. The data from excluded infants and from specimens deemed unsatisfactory for testing were deleted from the dataset and excluded from analysis. Data were missing for < 2.7% of repeat samples. Cleaned data were collapsed and the final data set included: infant age at collection, week, month and year of birth, sex, gestational age, plurality status, birthweight, infant county, maternal age, and antibody test results. Infants with single, two and more than two specimens were stratified by demographic characteristics (GraphPad Software version 9.3.1, San Diego, CA). Logistic regression was used to test for associations between changes in antibody reactivity and demographic factors. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multicollinearity tests were performed to assess for confounding variables among demographic factors and all variance inflation factors were < 2 excluding interaction terms.

Decay of maternally-derived antibodies

To assess the decay of passively acquired antibodies, linear mixed effects models were used to estimate the pattern of decline in antibody reactivity, following the general approach of Wheatley et al.19. The analysis was conducted in R 4.3.020 using the lme4 package21. Infants with more than two specimens that were S SARS-CoV-2 IgG reactive at birth were selected for this analysis (Fig. S1). MFI index values were natural-log transformed. Infant ID was included as a random effect (intercepts) and the age of infant in days as a fixed effect. Prior literature has found non-linear patterns of antibody decay19,22, so we added an indicator variable equal to the age of the infant in days, minus a threshold value. Any resulting negative values were set to zero. As we had no a priori expectation of when this threshold would occur, we used a consistent 30-day threshold across all analyses to facilitate comparisons.

We examined the potential for demographic characteristics to affect the rate of acquired antibody decay by including demographic traits as fixed effects in the mixed models regression. Models with the lowest delta-AIC (Akaike Information Criterion)23 scores were selected as the most-supported. Unlike S IgG, inclusion of gestational age and an interaction with age improved the model for N IgG. Consequently, N IgG antibody half-lives were also calculated separately per gestational age category.

Slope was extracted from the mixed models to evaluate SARS-CoV-2 IgG half-lives (equations [EQNs] 1 and 2), where tij is the age for infant i for observation j, adjusted with a 30-day threshold (\(T_{0} )\). β0 is the intercept, b0i is an infant-specific random intercept, β1 is the coefficient for age, sij is the threshold-adjusted age (Eq. 2), and β2 is the estimated coefficient for the threshold-adjusted age. Half-lives were calculated using the equation 0.693/(k + m), where k = -β1 and m = − β2, which simplifies to 0.693/k if threshold-adjusted age is not included in the model. 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated based on 1.96 times the standard error of the parameter estimates. For negative half-lives (i.e., where an increase was predicted instead of a decrease), the half-life was replaced by infinity (∞). To assess whether antibody decay rates varied with initial reactive index values (MFI index > 1), we categorized infants into those with initial low (< 5.0), intermediate (5–15), and high (> 15) MFI index values for S IgG and low (< 2.5), intermediate (2.5–5), and high (> 5) MFI index values for N IgG (Fig. S1). Different thresholds were chosen due to differences in the observed magnitudes of the respective indices.

Maternal derived antibody longevity

To analyze the duration of passively acquired S or N SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in infants, two approaches were used. First, for infants that were IgG antibody reactive at birth, the probability that the last sample was also reactive was estimated by binning the data and calculating the probability of reactivity for each bin. Observations were then binned with break points of 5,10,15,20,25,30,35,40,50,60,80,100,130,150,225 (e.g., the first bin would be 0 to < 5, the second 5 to < 10, etc.). Bin width increased with time due to decreased sampling at later time points. The 150 and 225 break points had no data and therefore excluded for N IgG. Second, a logistic regression was fit to each set of data (S and N) using the glm function in R. The goodness of fit was assessed visually and with the Hosmer–Lemeshow Goodness of Fit test. In the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, a significant result indicates a significantly poor fit, while a non-significant result fails to reject the hypothesis that the fit is bad (i.e., non-significance does not guarantee a good fit, but significance does indicate a poor fit).

Seroconversion patterns and rates

SARS-CoV-2 IgG, IgA, and IgM seroconversion patterns and rates were estimated in a subset of infants with more than two specimens that were initially non-reactive for S and N IgG, and later developed S or N IgG antibody reactivity (see Supplement S2).

Research approvals

This study used remnant dried blood spots from newborns that were submitted to the New York State Newborn Screening program. Remnant DBS samples that have been deidentified can be used for public health research. Parents and/or legal guardians may opt out of the use of remnant deidentified newborn screening specimens for public health research. They may also have their infant’s specimen destroyed. Specimens from infants whose parents and/or legal guardians opted out of public health research were excluded from this study. Approval for human subjects research, including all experimental protocols in this study, was obtained from the NYS Department of Health Institutional Review Board (protocol 20–023). All study procedures were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This study was approved by the New York State Department of Health Institutional Review Board, which waived informed consent because only deidentified residual specimens were used.

Results

Infant demographics and SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence

This longitudinal analysis included a total of 100,318 newborn screening DBS collected from 50,036 infants between November 2019 and November 2021 who met the inclusion criteria for repeat specimens. Infants with repeat specimens are a select group of infants with an initial sample collected within 4 days of birth as described in detail in the methods section. Data analyses were performed on various groups of infants from this study. See Fig. S2 for a diagram of cohorts and analyses performed.

To evaluate the characteristics of infants with repeat specimens, we compared infants with two specimens (n = 30,344) or more than two specimens (n = 19,692) to a larger subset of infants with a single specimen (n = 377,587) (Fig. 1). As expected, infants with either two or more than two specimens were more likely to be premature (27.3% and 68.3%, respectively) and from a multiple birth (7.3% and 17.9%, respectively) compared to infants with a single specimen (4.8% premature, 2.2% multiple birth). Infants with repeat specimens were also more likely to be of low (18.9% and 41.3%, respectively) and very low (3.3% and 19.8%, respectively) birthweight (BW) compared to infants with single specimens (4.2% low BW and 0.2% very low BW). In addition, infants with two and more than two specimens were more likely to be male (54.3% and 54.8%, respectively) and less likely to be born to individuals 20–30 years old (42.5% and 41.9%, respectively) than those with a single specimen (50.3% male, 45.1% born to individuals 20–30 years old) (Fig. 1).

Demographic characteristics of infants born in NYS between November 2019 and November 2021 with single, two or more than two specimens. Mean percentage (and 95% CI) of infants with single, two or more than two specimens per (a) gestational age (wk), (b) birthweight (g), (c) sex, (d) maternal age (y), and (e) multiple birth status.

To evaluate SARS-CoV-2 antibody reactivity in infants with single or repeat specimens, we tested DBS for IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 S and N antigens and evaluated demographic characteristics of initially reactive infants and the timing of antibody development11. Infants were grouped based on antibody reactivity at birth and, for nonreactive samples, subsequent antibody results. Overall reactivity for S or N SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies at birth was significantly higher in infants with a single specimen (n = 80,551; 21.3%, 95% CI 21.2–1.5%) than in infants with repeat specimens (n = 9,611; 19.2%, CI 18.9–19.6%) (Table 1). Of infants with repeat specimens, 630 (1.3%) were nonreactive for IgG antibodies at birth and developed either S or N antibodies in subsequent specimens (Table 1).

Antibody reactivity in infants with single or repeat specimens was analyzed to identify associations with demographic characteristics of the infant and/or mother using logistic regression. When compared to infants that were IgG nonreactive at birth, infants that were antibody reactive at birth were less likely to be from a multiple birth (odds ratio [OR] 0.88, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.84–0.92, p < 0.001), less likely to be born with low birthweight (OR 0.95, CI 0.91–0.99, p = 0.01), less likely to have repeat DBS specimens (OR 0.93, CI 0.90–0.96, p < 0.001), and less likely to have both repeat specimens and very low birthweight (OR: 0.67, CI 0.55–0.83, p < 0.001). Antibody reactive infants were more likely to be born to individuals > 30 years old (OR 1.15, CI 1.10–1.21, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

To evaluate the patterns of SARS-CoV-2 antibody reactivity, we plotted percent reactivity in the initial birth DBS of infants with single or repeat specimens over the 25-month period beginning November 2019 (Fig. 2). All infants born before March 2020 were nonreactive for both S and N SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies. The percentage of infants with reactivity to S or N SARS-CoV-2 IgG increased from March 2020 through June 2020, increased again from November 2020 through April 2021, and continued to increase from July 2021 through November 2021, corresponding to the increase in infections and COVID-19 vaccinations among individuals giving birth during this period (Fig. 2). Throughout the study period, initial antibody reactivity among infants with repeat specimens was lower than in infants with single specimens, but patterns of reactivity were similar.

SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) and nucleocapsid (N) antibody reactivity in NYS infants with single or repeat specimens between November 2019 and November 2021. Percentage of infants with single or repeat specimens born S+ or N+ SARS-CoV-2 antibody reactive (S+N+) (left y-axis, circles or squares, respectively) by month of birth. Percentage of infants with repeat specimens born SARS-CoV-2 antibody non-reactive who became S+ or N+ antibody reactive in a post-birth specimen (S–N– to S+ or N+) (right y-axis, triangles) by midpoint month between initial and last specimen.

Infants with repeat collections that were nonreactive at birth and developed S or N antibody reactivity in subsequent samples were analyzed to identify periods of seroconversion between November 2019 and November 2021. Seroconversion in the infant post-birth is likely due to the infant becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2 and developing their own antibodies, since infants who were noted to have received blood transfusions were excluded from the study. The estimated seroconversion date was calculated as the midpoint between the collection dates of the birth and the final specimen. The first estimated seroconversion, where an infant developed SARS-CoV-2 antibody reactivity post-birth, occurred in an infant who was non-reactive at birth in February 2020 and seroconverted by March 2020, a period which coincided with the first reported cases of COVID-19 in NYS. The percentage of infants who seroconverted post-birth rose in September 2021 and declined by November 2021 (Fig. 2).

Longitudinal analysis of infant SARS-CoV-2 antibodies

Next, we evaluated longitudinal changes in antibody reactivity in infants with more than two DBS. We chose this population because the average time between the first and last specimen was greater in infants with more than two specimens (22.7 ± 0.2 days), compared to infants with two specimens (11.4 ± 0.1 days). This would allow more time to elapse between specimens, increasing our ability to detect changes in antibody reactivity. However, infants with more than two specimens were demographically different from infants with a single specimen, especially with regards to birthweight and gestational age (Fig. 1). As such, we examined the effect of these factors on longitudinal changes in antibody reactivity in subsequent analyses.

Maternally-derived SARS-CoV-2 antibody decay in infants

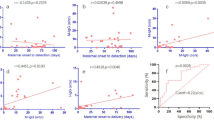

Infants passively acquire IgG maternal antibodies during pregnancy and titers of these maternal antibodies decay over time. We analyzed SARS-CoV-2 antibody decay in infants with more than 2 samples using linear mixed-effects modeling, including 2,400 infants with S reactive IgG antibodies and 579 infants with N reactive IgG antibodies passively acquired. A selective analysis was used to exclude infants who may have seroconverted in utero and whose antibody levels increased post-birth, by restricting the dataset to infants who were initially antibody reactive (MFI index > 1) at birth and whose antibody levels had declined in the last specimen collected from that infant (Fig. S1). In this population, antibody levels declined in a non-linear process, exemplified by a rapid decay in the first 30 days followed by a slower decay (Fig. 3). Half-lives were estimated for infants born S (and N) IgG antibody reactive for each of these periods (0–30 days after birth, > 30 days after birth), including infants with initially high, intermediate, and low levels of antibody (Fig. 3, Table 3, Table S1, Table S2). Half-life is the time required for the concentration of maternal IgG antibodies to decrease by half. Overall, S and N IgG half-life estimates were significantly lower 0–30 days after birth (22.8 and 22.1 days, respectively) compared to > 30 days after birth (37.5 and 36.6 days, respectively), confirming our observation of a faster rate of decay for the first 30 days followed by a slower decay after 30 days. This pattern (longer half-lives after 30 days) was consistent at low, intermediate, and high levels of S IgG and N IgG, although not all categories were significantly longer. Within each period (0–30 and > 30 days), half-lives were not significantly different between low, intermediate, and high initial antibody levels. Therefore, initial high reactivity was expected to persist longer than low and intermediate reactivity, due to higher initial MFI index values (Fig. 3) with similar rates of decay.

Natural log of MFI index values for infants born SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody reactive for (a–d) spike (S) and (e–h) nucleocapsid (N). Antibody decay in the total population (a,e) or in subgroups of infants with initial high (b,f), intermediate (c,g) and low (d,h) levels of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies. Slopes for antibody reactive infants were allowed to change after 30 days to provide a linear approximation to the non-linear decay process.

Since our dataset includes a high proportion of infants who were born premature or with low or very low birthweight, we determined if these characteristics impacted half-life estimates. Although not significant, half-life estimates of N IgG > 30 days after birth were lower in premature infants than in infants with normal gestational age (95% CIs barely overlapped, Table 3).

Alternative models can be useful to analyze non-linear patterns of antibody decay. We used logistic regression to analyze antibody decay in 2,400 infants reactive for S IgG and 579 infants reactive for N IgG based on the mean probability, for an infant that was previously reactive, that their next sample would be non-reactive (i.e. seroreversion). We estimated a mean IgG seroreversion probability of 56 days for S and 28 days for N (95% CI 50–62 for S and 95% CI 24–33 days for N, respectively) (Fig. 4, Table S3).

Probability of non-reactive SARS-CoV-2 (a) spike (S) IgG and (b) nucleocapsid (N) IgG antibodies in subsequent specimens collected from infants born in NYS. Black dots indicate reactive (1’s) and non-reactive (0’s) infants. Blue dots show the percent of infants within each bin that were reactive. Hosmer–Lemeshow Goodness of Fit test p = 0.49 for S IgG and p = 0.381 for N IgG. Sample sizes were 2,400 infants for S IgG and 579 infants for N IgG. Shading indicates a 95% confidence interval of the mean probability estimate. The probability of a reactive repeat specimen dropped below 50% after 56 days for S IgG (95% CI 50–62 days) and was 28 days for N IgG (95% CI 24–33 days).

Infant SARS-CoV-2 antibody seroconversion

Of 19,692 infants with more than two specimens, seroconversion was detected in 240 infants who were nonreactive for SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in the initial specimen but became reactive in subsequent collections. Twenty-three infants seroconverted for both S and N IgG, 205 for S IgG only, and 12 for N IgG only.

IgG in newborns is indicative of passive acquired immunity24, whereas detection of IgM and IgA post-birth suggests active immunity. Therefore, to confirm that infants had seroconverted, we retested a select group of 34 IgG seroconverting infants for the presence of SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgA antibodies (see Supplement S3). Five patterns of seroconverting antibody isotypes were observed (see Fig. 5 for representative examples): synchronous S or N IgG, IgM and IgA (8 infants), synchronous S or N IgG and IgA (10 infants), synchronous S or N IgG and IgM (3 infants), S IgG only (13 infants), and infants born S IgG reactive that subsequently seroconverted for either IgA or IgM (9 infants). Of infants who seroconverted for IgG post-birth, 20.6% (and 29.4%) of infants seroconverted to S (and N) IgM, and 52.9% (and 20.6%) seroconverted to S (and N) IgA. We also used a modeling approach to evaluate antibody seroconversion rates in this population (see Supplement S2). Detection of IgA and IgM in several infants confirmed seroconversion for SARS-CoV-2 in this population.

Antibody levels (ln(MFI Index)) against SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) and nucleocapsid (N) in individual infants with 3 or more DBS who seroconverted between initial and subsequent samples (a.-h., 34 infants) or were initially seropositive for IgG S and seroconverted for IgA or IgM (i.-j., 9 infants). Horizontal dotted line indicates reactive cutoff (ln(MFI Index) = 0). Infant identifiers are given at the top of each panel for reference.

We also tested 144 infants that were reactive for S IgG at birth to identify if any had detectable IgM and IgA at birth, which could indicate in utero infection (see Supplement S3). One infant was reactive for N IgM (ID 6695101) at birth. No IgM or IgA was detected in the birth specimen of the remaining 143 infants that were IgG positive at birth. We also determined if these initially IgG reactive infants had later seroconverted for IgM or IgA, a finding that would indicate an infection post-birth. Of the 9 infants that seroconverted for IgA or IgM but were reactive for S IgG at birth, one (ID 1905147) seroconverted > 4 weeks post-birth and became reactive for N IgG, N and S IgA, and N and S IgM. Of the remaining eight, five seroconverted for N IgA and three seroconverted for N IgM. Interestingly, S IgG appeared to decline in four infants while N IgA or N IgM increased. This unique pattern may be explained by maternal derived S IgG antibody decay that masked an infant derived S IgG antibody response.

Discussion

We investigated longitudinal changes in SARS-CoV-2 antibody reactivity in a population of infants with repeat newborn screening DBS specimens. In NYS, repeat newborn specimens are recommended for unsuitable initial specimens, borderline testing results, and from high-risk infants. As predicted, compared to demographic characteristics of infants with single DBS collections, infants with two or more than two specimens were more likely to be premature, from multiple births and with low or very low birthweight.

Our analysis of SARS-CoV-2 antibody reactivity of infants revealed that infants with repeat samples were less likely to be reactive than infants with single specimens. Reactive infants were also less likely to be from a multiple birth and have low or very low birthweight, but more likely to be born to individuals > 30 years old. In our previous serosurvey that analyzed the initial specimen from all 415,293 infants in our study11, multiple births were associated with higher S and lower N reactivity. In addition, our previous study, similar to this one, found lower S and N reactivity in infants with low and very low birthweight, and higher reactivity for S, but not N, in infants born to individuals > 30 years old11. We found no association between antibody reactivity and gestational age or infant gender.

Fluctuations of S and N SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies that were passively transferred pre-birth or actively acquired post-birth were compared over the 25-month study period. Infants with either single or repeat specimens born with reactivity to S or N SARS-CoV-2 IgG had similar patterns to that reported in our previous study, where we saw that reactivity followed peaks of COVID-19 cases in NYS and increased use of vaccines11. In the current study, reactivity in infants with single specimens was higher than in infants with multiple specimens. The first peak of post-birth IgG seroconversions among infants in NYS with repeat specimens was in February-June 2020, followed by a slow and steady increase in seroconversions from July 2020 to Aug 2021, followed by a second peak in September–October 2021, in parallel with the onset and subsequent rise of COVID-19 cases. In a population-based survey, SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels in the winter of 2020–2021 increased at the beginning of vaccine implementation in NYC25. Specific to the first vaccinations in pregnant individuals in January 2021, seroprevalence in infants with single and repeat specimens born with IgG reactivity rose through April 2021. By November 2021, we found a decline in infants who seroconverted post-birth, which is likely an artifact of our study end date, as some infants born in November 2021 would not have had time for repeat specimens to be collected prior to the study end date of November 30, 2021.

The longevity of maternally acquired antibodies in infants is dependent on many factors, including the time of SARS-CoV-2 maternal infection or vaccination relative to the pregnancy, the length of time for transplacental transfer, gestational age, and initial antibody levels at birth12,15,26,27,28,29. Infants with IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 detected in the initial specimen and with at least two subsequent DBS were analyzed for S and N SARS-CoV-2 antibody waning. Using linear mixed models, we found that antibodies declined in a non-linear fashion, more quickly for days 0–30 after birth and more slowly > 30 days. Maternal-acquired IgG antibody half-lives were estimated in infants born SARS-CoV-2 antibody reactive by selecting infants with antibody reactivity at birth that declined with age. Overall, the half-lives of IgG N and S antibodies was 22–23 days for days 0–30 after birth and increased to 37–38 days > 30 days. Prior research has shown a dramatic decline in passively acquired antibodies 2–6 months postpartum in infants30, with half-lives of maternal IgG in infants of 30 days31. Half-life estimates did not differ significantly between N and S antibodies, high, intermediate, or low initial antibody levels, nor by gestational age. Our results differ from a previous report that showed that SARS-CoV-2 N IgG antibody decay rates in adults are dependent on initial antibody levels, with faster decay in high verses low initial IgG levels32. In contrast, a smaller cohort study suggests infant SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody duration is positively associated with initial cord blood levels12. In addition, infants born to individuals who seroconverted as a result of infection have lower antibody persistence33 compared to infants born to individuals with vaccine-acquired antibodies, perhaps due to higher antibody levels generated following vaccination. A multi-slope comparison throughout the decay process may be useful to explain these differences. Initial infant antibody indices are positively associated with higher IgG transplacental transfer ratios in second-trimester maternal infections13,34. Collectively, results are mixed regarding the effect of antibody levels on the rate of maternal antibody decay in infants.

When decay rates are consistent, higher initial antibody levels will result in longer antibody persistence. Our analysis of passive acquired antibody decay found higher initial S IgG indices compared to N IgG, and similar half-lives of S and N IgG, in agreement with longer persistent S IgG acquired antibodies35. Furthermore, shorter N IgG half-life estimates in infants of earlier gestational age (Table 3) may be explained by a lower transplacental transfer of maternal antibodies, as previously reported36,37. Compared to stable and longer lasting maternal SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies in adults, reports of a rapid antibody decay in infants may be a result of dependence on the neonatal Fc receptor expression14,30,31,38. Average adult half-lives of SARS-CoV-2 N and S IgG antibodies range between 35 and 85 days and 87 and 184 days, respectively, with IgM and IgA antibodies declining more rapidly39,40,41,42,43. Additional longitudinal analysis of SARS-CoV-2 antibody response in maternal-newborn dyads, pre- and post-vaccination, would be useful to develop a better understanding of infant SARS-CoV-2 antibody longevity.

Transplacental antibody transfer is restricted to immunoglobulin G subtype, IgG, by specificity of the neonatal FcN receptor44. Transplacental infection of the fetus with SARS-CoV-2 is uncommon, therefore detection of fetal-derived IgM or IgA at birth due to intrauterine infections is rare45,46. Of the 144 infants that were IgG reactive at birth and whose initial birth specimen was retested for IgM and IgA, N IgM antibodies were detectable in a single specimen from an infant reactive for S IgG, but further evaluation of this individual would be necessary to confirm the result. IgM or IgA antibodies to S or N SARS-CoV-2 were not detected in any other birth specimens from the infants retested in this study.

Infants with two or more subsequent DBS whose initial DBS was antibody non-reactive, but who developed SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in subsequent samples were analyzed for seroconversion. A total of 630 infants (1.3%) in the larger repeat sample cohort and 240 in the > 2 sample group (1.2%) seroconverted during this period. We retested DBS from a select group of these seroconverting infants and detected IgA and IgM S and N antibodies, confirming seroconversion in these infants. Breastmilk-derived SARS-CoV-2 antibodies are not transferred into infantile circulation and are not measurable in infant serum and DBS samples47,48, therefore measurable IgA and IgM antibodies in DBS are a result of the infant’s antibody response. Previous studies have reported that infant IgG and IgM seroconversion12 and adult IgG, IgM and IgA seroconversion occurred by 2 weeks49,50, suggesting similar seroconversion rates among infants and adults. Compared to adults, children have lower S SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity, predominantly synthesize S IgG antibodies, negligible amounts of N IgG antibodies, and low and variable levels of S IgM and IgA antibodies51,52. Previous studies also indicate synchronous seroconversion of IgG and IgM SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among adults50, but few studies have analyzed infant seroconversion patterns of SARS-CoV-2 antibody isotypes. We report four patterns of synchronous seroconversion of IgG, IgM, and IgA SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in infants (Fig. 5).

A strength of this study is the large cohort of unique infants with repeat DBS specimens collected over a 25-month period, extending from prior to the pandemic through vaccine implementation in NYS. Limitations include a restricted set of demographics that was derived from what was available to the NSP at the time of collection, repeat specimens that were only available from a subset of infants who needed follow-up screening, and no information about maternal SARS-CoV-2 infections or vaccinations. Because infants with repeat samples were more likely to be premature, from a multiple birth or have low birthweight, the results of this study cannot be generalized to all newborns.

This longitudinal study of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in infant DBS demonstrates the benefits of using existing newborn screening DBS for large-scale population wide serological analyses. Our previous study utilized the same samples but restricted the analysis to the first sample from each infant11. Here we focused our analysis on infants with multiple samples, which allowed us to evaluate antibody decay and detect several hundred infants who seroconverted to SARS-CoV-2 over the 25-month study period. We modelled maternal antibody decay in this population using multiple statistical methods and confirmed seroconversion of select infants via the detection of IgM and IgA antibodies.

Data availability

The data supporting this publication will be available at ImmPort (https://www.immport.org) under study accession SDY3122. Contact the corresponding author to request access.

References

Li, K. et al. Dynamic changes in anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies during SARS-CoV-2 infection and recovery from COVID-19. Nat. Commun. 11(1), 6044. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19943-y (2020).

Qu, J. et al. Profile of immunoglobulin G and IgM antibodies against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Clin. Infect. Dis. 71(16), 2255–2258. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa489 (2020).

Lindsey, B., Kampmann, B. & Jones, C. Maternal immunization as a strategy to decrease susceptibility to infection in newborn infants. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 26(3), 248–253. https://doi.org/10.1097/QCO.0b013e3283607a58 (2013).

Zava, T. T. & Zava, D. T. Validation of dried blood spot sample modifications to two commercially available COVID-19 IgG antibody immunoassays. Bioanalysis 13(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.4155/bio-2020-0289 (2021).

Karp, D. G. et al. A serological assay to detect SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in at-home collected finger-prick dried blood spots. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 20188. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76913-6 (2020).

McDade, T. W. et al. High seroprevalence for SARS-CoV-2 among household members of essential workers detected using a dried blood spot assay. PLoS ONE 15(8), e0237833. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237833 (2020).

Valentine-Graves, M. et al. At-home self-collection of saliva, oropharyngeal swabs and dried blood spots for SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis and serology: Post-collection acceptability of specimen collection process and patient confidence in specimens. PLoS ONE 15(8), e0236775. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236775 (2020).

Schultz, J. S. et al. Development and validation of a multiplex microsphere immunoassay using dried blood spots for SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence: Application in first responders in Colorado, USA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 59(6), e00290-e321. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00290-21 (2021).

Styer, L. M. et al. High-throughput multiplex SARS-CoV-2 IgG microsphere immunoassay for dried blood spots: A public health strategy for enhanced serosurvey capacity. Microbiol. Spectr. https://doi.org/10.1128/Spectrum.00134-21 (2021).

Nemeth, K. L. et al. Use of self-collected dried blood spots and a multiplex microsphere immunoassay to measure IgG antibody response to COVID-19 vaccines. Microbiol. Spectr. 11(1), e0133622. https://doi.org/10.1128/spectrum.01336-22 (2023).

Damjanovic, A. et al. Utility of newborn dried blood spots to ascertain seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies among individuals giving Birth in New York State, November 2019 to November 2021. Jama Netw. Open 5(8), e2227995. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.27995 (2022).

Song, D. et al. Passive and active immunity in infants born to mothers with SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 11(7), e053036. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053036 (2021).

Mo, H. et al. Detectable antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in newborns from mothers infected with COVID-19 at different gestational ages. Pediatr. Neonatol. 62(3), 321–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedneo.2021.03.011 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Dynamic changes of acquired maternal SARS-CoV-2 IgG in infants. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 8021. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-87535-x (2021).

Shook, L. L. et al. Durability of anti-spike antibodies in infants after maternal COVID-19 Vaccination or natural infection. JAMA 327(11), 1087–1089. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.1206 (2022).

Liu, F. et al. Newborn dried blood spots for serologic surveys of COVID-19. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 39(12), e454–e456. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0000000000002918 (2020).

Nir, O. et al. Maternal-neonatal transfer of SARS CoV-2 IgG antibodies among parturient women treated with BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine during pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100492 (2021).

Martin, M. A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 specific antibody trajectories in mothers and infants over two months following maternal infection. Front. Immunol. 13, 1015002. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.1015002 (2022).

Wheatley, A. K. et al. Evolution of immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 in mild-moderate COVID-19. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 1162. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21444-5 (2021).

R Core Team. R: A Language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2023 (Vienna, Austria).

Bates, D., Machler, M., Bolker, B. M. & Walker, S. C. Fitting linear mixed-effects models Using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01 (2015).

Yamayoshi, S. et al. Antibody titers against SARS-CoV-2 decline, but do not disappear for several months. EClinicalMedicine 32, 100734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100734 (2021).

Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Automat. Control 19(6), 716–723. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705 (1974).

Arnold, T. W. Uninformative parameters and model selection using Akaike’s information criterion. J. Wildlife Manage. 74(6), 1175–1178. https://doi.org/10.2193/2009-367 (2010).

Parrott, J. C. et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies during phased access to vaccination: Results from a population-based survey in New York City, September 2020–March 2021. Epidemiol. Infect. 150, 105. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268822000875 (2022).

Beharier, O. et al. Efficient maternal to neonatal transfer of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 and BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. J. Clin. Invest. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI150319 (2021).

Zdanowski, W. & Wasniewski, T. Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein antibody titers in cord blood after COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy in polish healthcare workers: Preliminary results. Vaccines (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9060675 (2021).

Atyeo, C. et al. Compromised SARS-CoV-2-specific placental antibody transfer. Cell 184(3), 628-642e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.027 (2021).

Adhikari, E. H. & Spong, C. Y. COVID-19 vaccination in pregnant and lactating women. JAMA 325(11), 1039–1040. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.1658 (2021).

Martin-Vicente, M. et al. Antibody levels to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in mothers and children from delivery to six months later. Birth https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12667 (2022).

Rottenstreich, A. et al. Kinetics of maternally derived anti-severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) antibodies in infants in relation to the timing of antenatal vaccination. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76(3), e274–e279. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac480 (2023).

Xia, W. et al. Longitudinal analysis of antibody decay in convalescent COVID-19 patients. Sci. Rep. 11(1), 16796. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96171-4 (2021).

Shook, L. L. et al. Durability of anti-spike antibodies in infants after maternal COVID-19 vaccination or natural infection. JAMA https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.1206 (2022).

Capretti, M. G. et al. Infants born following SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnancy. Pediatrics https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-056206 (2022).

Ratcliffe, H. et al. Serum HCoV-spike specific antibodies do not protect against subsequent SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents. iScience 26(12), 108500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.108500 (2023).

van den Berg, J. P. et al. Lower transplacental antibody transport for measles, mumps, rubella and varicella zoster in very preterm infants. PLoS ONE 9(4), e94714. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094714 (2014).

Pou, C. et al. The repertoire of maternal anti-viral antibodies in human newborns. Nat. Med. 25(4), 591–596. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0392-8 (2019).

Pyzik, M. et al. The neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn): A misnomer?. Front. Immunol. 10, 1540. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01540 (2019).

Lumley, S. F. et al. The duration, dynamics, and determinants of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) antibody responses in individual healthcare workers. Clin. Infect. Dis. 73(3), e699–e709. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciab004 (2021).

Anna, F. et al. High seroprevalence but short-lived immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in Paris. Eur. J. Immunol. 51(1), 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.202049058 (2021).

Dan, J. M. et al. Immunological memory to SARS-CoV-2 assessed for up to 8 months after infection. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abf4063 (2021).

Dobano, C. et al. Immunogenicity and crossreactivity of antibodies to the nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2: Utility and limitations in seroprevalence and immunity studies. Transl. Res. 232, 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trsl.2021.02.006 (2021).

Wei, J. et al. Anti-spike antibody response to natural SARS-CoV-2 infection in the general population. Nat. Commun. 12(1), 6250. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-26479-2 (2021).

Palmeira, P., Quinello, C., Silveira-Lessa, A. L., Zago, C. A. & Carneiro-Sampaio, M. IgG placental transfer in healthy and pathological pregnancies. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2012, 985646. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/985646 (2012).

Kimberlin, D. W. & Stagno, S. Can SARS-CoV-2 infection be acquired in utero? More definitive evidence is needed. Jama-J. Am. Med. Assoc. 323(18), 1788–1789. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4868 (2020).

Kotlyar, A. M. et al. Vertical transmission of coronavirus disease 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 224(1), 35-53e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.07.049 (2021).

Lebbe, B., Reynders, M. & Van Praet, J. T. The transfer of vaccine-generated SARS-CoV-2 antibodies into infantile circulation via breastmilk. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 158(1), 219–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.14152 (2022).

Schwartz, A. et al. Presence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in lactating women and their infants following BNT162b2 messenger RNA vaccine. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 225(5), 577–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.07.016 (2021).

Roltgen, K. et al. Defining the features and duration of antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection associated with disease severity and outcome. Sci. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciimmunol.abe0240 (2020).

Long, Q. X. et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 26(6), 845–848. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0897-1 (2020).

Weisberg, S. P. et al. Distinct antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in children and adults across the COVID-19 clinical spectrum. Nat. Immunol. 22(1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-020-00826-9 (2021).

Toh, Z. Q. et al. Comparison of seroconversion in children and adults with Mild COVID-19. Jama Netw. Open 5(3), e221313. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1313 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Funding/Support: This study was supported by the CDC Foundation through contributions to its Emergency Response Fund. Dr Damjanovic, Ms Yauney, and Ms Nemeth were supported by cooperative agreement NU50CK000516 with the CDC. Mr Ehrbar was supported by Serological Sciences Network grant U01CA260508 from the National Cancer Institute. The members of the Wadsworth Center’s Newborn Screening Laboratory and Bloodborne Viruses Laboratory assisted with retrieving and punching blood spot cards. The Wadsworth Center Media and Tissue Core provided coupling and testing buffers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.D., L.S., A.K. and M.P drafted the manuscript; A.D., L.S., A.K., K.N., J.R., R.B., D.K., D.E., M.P. and M.C. revised the manuscript; A.D., A.K., and D.E. provided statistical analysis; M.C. obtained funding; K.N., E.Y., J.R., R.B., and D.K. provided technical support; L.S. and M.P. provided supervision of the project and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Damjanovic, A., Keyel, A., Rock, J.M. et al. Longitudinal analysis of passively and actively acquired SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in infants with repeat newborn screening samples. Sci Rep 15, 23881 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09140-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09140-6