Abstract

Biomolecular condensation has been extensively studied recently, yet advanced analytical methods for characterizing phase-separated systems remain limited. We developed a Python-based computational pipeline compatible with desktops and HPC systems that quantifies morphological heterogeneity in biomolecular condensates through a user-friendly Jupyter notebook platform. Our approach employs advanced morphological features, including Euler characteristic number and fractal dimension, to describe subtle spatiotemporal information from biomolecular condensates. We implemented robust statistical analyses besides conventional descriptors, incorporating skewness and kurtosis for asymmetric data distribution, and multivariate analysis through interactive principal component analysis (PCA) visualization combined with correlation and scree plots. The proposed statistical framework was applied to study the condensation of the neurodevelopmental protein DDX3X, which assembles spherical droplets in-vitro. The presence of PEG3350 as a crowding agent induced the formation of condensates with altered morphology. Furthermore, the R376C mutant, linked to neurodevelopmental disorders, formed elongated aggregates over time. Our pipeline’s tools for live plotting, phase diagram analysis, and high-throughput automation enable detailed investigation of condensate assembly dynamics, advancing standardization of morphological descriptor analysis of biomolecular condensates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

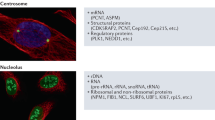

Liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) occurs when a homogeneous mixture of polymers spontaneously separates into a condensed, polymer-rich phase, which is in equilibrium with a dilute phase1,2. In particular, LLPS is a critical biophysical phenomenon that governs the spatiotemporal organization of the intracellular space by compartmentalizing biomolecules inside membraneless organelles (MLOs), including nucleoli, stress granules, and P-bodies3,4. MLOs facilitate several biological processes, such as RNA metabolism, protein synthesis, and stress responses, thus having important roles in cellular signaling, gene expression, and the organization of complex biochemical pathways3,4.

Biomolecular condensation is driven by weak, multivalent interactions (e.g., electrostatic, π-π stacking and hydrophobic interactions) among biological macromolecules5. These interactions are generally reversible and lower the free energy, promoting a liquid state that allows dynamic regulation1,6. Multivalency is associated with the presence of multiple short linear motifs (SLiMs) and/or folded associative domains, which expose hot spots that contribute to stereospecific intermolecular interactions1,6. Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) of proteins can serve as scaffolds for associative motifs, as generators of multivalency, thus enabling phase separation7.

In phase-separated systems such as liquid biomolecular condensates, reducing the surface area lowers the energy cost of forming the interface between the condensed and diluted phases5. As a result, the most thermodynamically favorable shape of the liquid droplet is a sphere, which has the smallest surface-to-volume ratio5. Isotropic forces among the biomolecules favor the spherical shape of the droplet, which is symmetrical in all directions. Spherical droplets are easily formed due to the fluidity of the macromolecules within the condensate, allowing optimal exchange with the diluted phase5. These spherical droplets can fuse and coalesce, which is also indicative of the liquid behavior5,8.

In some cases, the forces between the macromolecules are not perfectly isotropic, leading to elongation or other non-spherical shapes5. Besides, in the presence of external constraints or boundaries, such as in crowded environments of the cytoplasm, condensates may be deformed by external interactions, leading to non-spherical shapes5. Spinodal decomposition produces condensates displaying a variety of morphologies besides the spherical shape, including cylinder, slab, hollow cylinder, and hollow sphere8,9. Depending on factors such as confinement, droplet size, and cooling rates during the phase separation process, the dense phase can exhibit complex internal morphologies, such as core–shell structures or bicontinuous morphologies10. For instance, lysozyme solutions undergoing spinodal decomposition show a bicontinuous structure with a protein-poor fluid interpenetrating a dense glassy protein network8,9. The different morphologies of the condensate reflect the finite size of the system, where the surface energy becomes nonnegligible compared to the free energy within the dense phase11.

Certain condensates can also mature and undergo a transition from liquid to a more solid or gel-like non-spherical state, where stronger intermolecular interactions dominate12,13,14. This maturation frequently results in the formation of fibrous structures (e.g., amyloid fibrils). This involves a shift in the balance between enthalpic contributions (strong, directional interactions such as hydrogen bonding in β-sheets) and entropic penalties (loss of conformational flexibility)5. Dysregulation of LLPS and formation of fibrillar aggregates are implicated in several diseases, including neurodegenerative disorders like Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) and Alzheimer’s disease, where aberrant phase transitions lead to the formation of toxic protein aggregates15,16.

Light microscopy has emerged as a valuable tool for quantifying phase diagrams of biomolecules as a function of relevant intensive parameters of the system. Quantitative analysis of protein condensation by light microscopy involves using fluorescently labelled biological macromolecules17,18,19,20,21. Biomolecular LLPS studies aim to follow droplet growth or dissolution under different conditions usually by assessing droplet number, diameter and/or area from 2D fluorescence images over time22. Label-free techniques such as differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy can also be applied to study the morphology of condensates23. Biomolecular condensation dynamics have been further studied by fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP)17, NMR spectroscopy24 and X-ray photon correlation spectroscopy (XPCS)25,26.

Although commonly used, imaging techniques often rely on manual analysis, which is labor-intensive, subjective, and prone to bias. Furthermore, the diversity of droplet morphologies, ranging from spherical to irregular shapes, requires a sophisticated approach to quantification and comparison of individual droplets under various conditions. To address these challenges, we present a computational pipeline designed to automate the statistical analysis of biomolecular phase behavior by extracting droplets morphological descriptors from experimental data and studying their distribution under different physicochemical conditions. Our pipeline is Python-based, using free and open-source libraries27 that allow high-throughput, unbiased analysis of LLPS dynamics, providing insights into size distribution, shape and surface characterization, fluorescence intensities and time-dependent changes of each individual droplet. Additionally, we calculate Euler number and fractal dimension, which can be informative to separate more complex and irregular shapes. This approach not only reduces human intervention but also enhances reproducibility and precision in LLPS studies.

Importantly, we integrated tools for the statistical analysis of condensates morphological descriptors, from conventional descriptive statistics such as parametric mean and standard deviation, to more robust non-parametric description, study of frequency distribution and multivariate analysis. The data distribution can be quantified and compared over the experiment using skewness and kurtosis. Positive skewness indicates that most of the shapes cluster on the left of a descriptor histogram, with a few elongated or extreme values on the right28. Conversely, negative skewness indicates that the left tail is longer or wider than the right28. Besides, kurtosis measures the tailedness of such probability distribution28. It indicates how much of the data is in the tails and the sharpness of the peak of the distribution. High kurtosis (i.e. leptokurtic) indicates a distribution with heavy tails and a sharper peak. On the contrary, low kurtosis (i.e. platykurtic) indicates a distribution with lighter tails and a flatter peak. Also, normal kurtosis, with a value near 3, indicates a distribution similar to the normal distribution in terms of tail thickness. Together, both skewness and kurtosis provide valuable insights in identifying patterns within the descriptors distribution across experimental groups and help to identify respective biophysical consequences.

We applied our computational pipeline to study the condensation of the neurodevelopmental protein DDX3X, an important RNA helicase involved in RNA metabolism and stress granule biogenesis29. Although DDX3X LLPS is garnering increasing interest30, this process is still highly understudied. We evaluated the effect of a crowding agent, PEG3350, in the LLPS process, showing that it leads to non-spherical droplet formation, based on extracted shape descriptors. We also show that the R376C mutation in DDX3X results in condensate aggregation over time. Our proposed computational pipeline and statistical framework facilitates a deeper understanding of the biophysical properties of biomolecular condensates of proteins such as DDX3X. Our results underscore the potential of this automated statistical framework to standardize LLPS analysis across diverse experimental conditions, thus advancing the study of protein phase behavior.

Results

Implementation of an automated image analysis method for segmentation and quantification of biomolecular condensate morphological descriptors

We developed a computational pipeline that processes biomolecular condensates fluorescence microscopy images with the objective of segmenting and extracting key morphological descriptors. It was built over the standards of the Operetta HCS platform (PerkinElmer) for file in tagged image file format (TIFF), although the image processing itself is suitable for any image acquisition system. Our proposed computational pipeline is made available in a Jupyter lab interface31 to facilitate user navigation and alterations when needed. It was made available as open-source code on GitLab (https://gitlab.com/murilo.carvalho/2024_llps_analysis.git) and image dataset on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14387077).

In the Operetta HCS platform (PerkinElmer), a single TIFF file is created for each image channel and Z-stack position. A single image file is then exported to the user specified data folder for each channel and Z-stack position at every region-of-interest (ROI). Experimental details must be informed by the user in a separate CSV file placed in a metadata folder, including at least information of the plate map: experiment date, plate well number, experiment number and replicate number.

In the Jupyter interface, an interactive field will scan all CSV metadata files containing experimental information in the metadata folder and list them in a dropdown menu. Once selected, a specific metadata file is loaded automatically and displayed for easy inspection. Through regular expression logic, the implemented pipeline extracts the metadata from the image files to retrieve the well number coordinates (row and column), the image field in the well, time step, the Z position and the image channel information. All metadata information is temporarily stored in a dataframe with all columns renamed to add the suffix “Metadata_” to the original variables. Next, it lists the TIFF files stored in the data folder, following the experiment date and path pattern. If several Z-stack images are acquired, it is requested to the user select the channel of interest and the Z-stack position that will be analyzed, starting from 1 (usually the bottom of the plate well). The list is then automatically populated.

The main function of the proposed pipeline is to segment droplets from all images, calculate the respective morphological descriptors and fluorescence intensities and return a temporary dataframe. The image segmentation procedure of biomolecular condensates is shown in Fig. 1. Extracted well number and the respective ROI are used to concatenate the dataframe with calculated descriptors with user-informed experimental metadata found in the CSV file. The corresponding TIFF file(s) is(are) then loaded and transformed into a NumPy array32 to speed up the calculations. The user must inform the effective pixel size, calculated based on the microscope optical system and usually embedded in the file metadata. Next, the image is equalized using a Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE) algorithm33,34 to enhance the contrast of the image using histograms computed over different tile regions of the image, reducing illumination artifacts. Noise is largely reduced by a non-local means filter, optimized by estimating sigma values previously35,36,37,38,39. The border of every droplet is enhanced by an unsharp mask filter40.

Biomolecular condensation analysis pipeline. Fluorescently labeled biological macromolecule(s) is(are) pipetted together with modulatory factor(s) stock solution in a 96 or 384-well plate. The plate is then positioned in the Operetta HCT (PerkinElmer) imaging platform. Fluorescence images are collected at 40X WD objective following a z-scan. Stored images are assembled with experimental metadata and processed in an HPC container-based parallelized image analysis pipeline using Python scripts. Raw images are segmented following normalization, denoising and enhancement of the raw images. Cropped objects are removed from the borders of the image. Fluorescence intensity of droplets is quantified by applying the cleaned binary masks to the raw images. Background is identified as the inverse of binary and eroded to avoid light scattering from the droplets. Morphology descriptors are then extracted and resulting dataframe are assembled for further statistical analysis.

After the regularization steps, single thresholding creates a binary image, isolating the droplets from the background. The Otsu algorithm41 is used to calculate the threshold value that putatively separates the objects from the background. The user can adjust this value to adapt the algorithm to particular images. Next, the objects that touch the image borders are removed from the analysis to prevent mistakes in statistics since they could be incomplete. Finally, a connected component analysis42,43 individualizes each droplet from the binary image into a label.

Additional parameters in the main function create informative panels of every step of the segmentation process, making it easy to verify if the pipeline is working correctly, giving the possibility of threshold optimization. If set to “True”, the function returns a panel with original, equalized, denoised, unsharp masked, binary thresholded, cleared, and labeled images (Fig. 1). All plots share the same axis and are synchronized by default so users can interact with them (zooming, panning, and saving representative images) by using, for instance, %matplotlib widget magic44,45 when running in the Jupyter interface.

An important action is to confirm whether the threshold value is optimal for droplet segmentation after initial filtering steps. This can be done by evaluating the “threshold” panel and comparing it with the original image. Although we use the Otsu algorithm41 to find threshold value, we sum a constant (k) value (with default value set to 0) to it, so users can increase or decrease the calculated Otsu value by using positive or negative values, respectively. This fine tuning makes processing adequate for different image acquisition methods, such as confocal or wide field microscopes. Similarly, it is possible to adjust the background definition by optimizing the erosion value. In this sense we prevent scattering from the droplets to be computed as background, which would impact the partition coefficient calculation as defined in Table 1 , reflecting the apparent concentration inside a single droplet.

Another parameter, namely numbered_label, exhibits the final image of segmented droplets in random colors with their respective labels (Fig. 1). Furthermore, all plots are saved in the respective dataset folders for further verification. Each segmented image presents every droplet as a single and unique object. As each droplet has a unique identifier number, users can spot their features in the dataframe and retrieve its position in the image. Feature calculations are performed using the regionprops function from the scikit-image library46. This function measures properties of individualized, labeled droplets in a few seconds even for hundreds of thousands of objects. The proposed pipeline additionally includes the option to calculate the fractal dimension of the condensate (by the Porespy library47, using box counting method) which quantifies the complexity and irregularity of droplet shapes by measuring their space-filling capacity and self-similarity across scales. For each droplet, it calculates descriptors, as defined in Table 1 , and the results are then organized in a Pandas dataframe48, for further integrated statistical and interactive analysis following the Jupyter notebook. We include an option to export the dataframe as a CSV file, suitable to any additional analysis in complementary statistical software such as R49.

Phase diagram visualization and statistical analysis

The interactive Jupyter pipeline offers a useful and interactive function to plot a phase diagram that aims to summarize the experimental data. Phase diagrams can be set to automatically plot a specific descriptor (e.g. morphological descriptor or intensities) according to one (1D) or two (2D) experimental variables in a heatmap display. When displaying the calculated values, an interactive range slider can be used to properly control the color scale. These droplet descriptors are initially set as the minimum and maximum values in the distribution, exhibited in a color bar (Fig. 2A). The whole plot and color bar are updated in real time. Additionally, the user can choose to plot representative raw images to illustrate the condition in each combination of parameters of the experiment. Finally, it is also possible to interact with plots of images zooming in, out or panning to choose a specific region of interest.

Tools for comparative analysis of biomolecular condensates. (A) Phase diagram tool. The user can plot graphs to comparatively visualize representative images (image = “True”) of representative conditions characterized by a combination of two physicochemical parameters. If image = “False”, it will show rectangles colored by a chosen descriptor value. The color bar indicates the range of calculated values that are displayed. (B) Examples of exploratory statistical analyses, such as descriptive skewness and kurtosis of the distribution, variable correlation, individual droplet visualization and principal component analysis (PCA).

Several statistical analyses can be performed following the examples available in the Jupyter notebook. First, the computational pipeline will return the total number of droplets, the mean, median, quartiles and range (minimum and maximum) of the selected descriptor as descriptive statistics, to summarize a given distribution of the whole dataset. It can also create groups by combining some single or multiple experimental conditions (e.g. protein concentration, salt type, incubation time, among others). Next, using grouping, it can calculate the skewness and kurtosis of the distribution of any descriptor (Fig. 2B).

To plot statistical parameters, Plotly50 was implemented directly or as a backend for Pandas dataframes48, which allows interaction for zooming, panning, hiding variables and exporting the final image. Histograms and scatter plots can be promptly displayed for analyzing the distribution of a single descriptor or the correlation between two descriptors, respectively (Fig. 2B). Experimental groupings are supported, and the droplet label is displayed for each individual condensate. An option to display the image of a particular droplet is also available by informing its index number. Furthermore, the distribution of a given descriptor can be shown as a violin plot, which also returns the respective descript statistics (Fig. 2B).

Finally, we also included a principal component analysis (PCA) tool for dimensionality reduction to facilitate pattern interpretation of the data by groups, with several menus and options to create interactive plots (Fig. 2B). PCA serves as a powerful mathematical descriptor for droplet condensates by transforming complex, multi-dimensional morphological data into a reduced set of uncorrelated variables that capture the most significant variance patterns, identifying the shape descriptors that contribute for droplets segregation, inferring biophysical properties associated with the experiment.

Application to the analysis of DDX3X condensation

We investigated human DDX3X condensation as a model of application for our proposed computational pipeline. Although it was recently demonstrated in-vitro and in cells30,51, DDX3X LLPS has not been extensively characterized. Thus, we followed, by fluorescence microscopy, recombinant, wild-type DDX3X-mCherry liquid condensation at room temperature from 1.25 to 10 μM protein concentration after 60 min incubation with ranging PEG3350 concentration from 0 to 5%. We observed mostly spherical droplets at high protein concentration (up to 10 μM) in the absence of crowding agent (Fig. 3A). The droplet area expanded with increasing protein concentration, with a circularity value close to 1 (Fig. 3B). This indicates that the global form of the condensates represents two-dimensional projections of spheres, which suggests a liquid phase rich in DDX3X-mCherry. Importantly, increasing concentrations of PEG3350 (up to 5%) resulted in both lower circularity and roundness (Fig. 3C) indicating deviation from the perfect circles. Roundness undergoes a pronounced reduction when PEG3350 concentration increases from 0 to 5% at a fixed protein concentration of 10 µM, whereas circularity exhibits only a minor decrease (Fig. 3B and C). Roundness is more sensitive than circularity to global shape changes, including elongation and aspect ratio shifts (Fig. 3C), because it directly depends on the major axis of the best-fit ellipse, which amplifies deviations from a perfect circle. Complementarily, circularity is sensitive to local boundary irregularities due to its reliance on perimeter, which is not observed at high PEG3350 concentrations (Fig. 3B and C). Solidity also indicates that condensates structural compactness and boundary regularity remain stable under these experimental conditions (Fig. 3B and C), although a significant increase in eccentricity quantifies condensate elongation in the presence of crowding agent (Fig. 3B and C). This indicates that while the overall boundary irregularity remains relatively constant, the droplets become more elongated or deformed globally in the presence of PEG.

Effect of macromolecular crowding on DDX3X condensation. (A–C) Phase diagram of DDX3X concentration versus PEG3350 concentration. (A) Representative fluorescence images of DDX3X condensates at 60 min incubation. (B) Phase diagrams colored by area, circularity, roundness, eccentricity, aspect ratio and solidity values. (C) Violin plots represent the frequency distribution of area, circularity, roundness, eccentricity, aspect ratio and solidity values for 10 μM DDX3X-mCherry in the presence of 0% or 5% PEG3350.

Our analysis revealed significant positive skewness in droplet area distributions at 10 μM protein concentration after 60 min of incubation, regardless of PEG3350 presence (Fig. 3C, Table 2). These distributions exhibit leptokurtosis, indicating longer tails than a normal distribution. This pattern likely arises from the coalescence of small droplets over time, leading to a wide range of droplet sizes. Notably, area distribution kurtosis increases in the presence of 5% PEG3350 (Fig. 3C, Table 2), suggesting that PEG3350 impairs droplet coalescence, preventing droplets from growing into larger-area objects. Conversely, the crowding agent decreases the kurtosis of the distributions of circularity and roundness in the presence of 5% PEG3350, supporting this hypothesis. Instead of forming larger, more circular droplets, droplets tend to merge and branch, producing condensates with irregular, noncircular borders (Fig. 3C, Table 2). Additionally, descriptors such as eccentricity, aspect ratio, and solidity further illustrate the biophysical effects on droplet dynamics. In the absence of PEG3350, these shape descriptors show distributions with a well-defined peak (Fig. 3C) and relatively high skewness (Table 2), indicating that most droplets have similar shapes, with only a few irregular outliers. In contrast, with PEG3350, droplets predominantly exhibit elongated shapes (e.g., higher aspect ratio) and irregular borders (e.g., lower solidity) (Fig. 3C), resulting in lower kurtosis of the morphological descriptors distributions. This shift demonstrates that droplet shape alterations are not exceptions in the presence of PEG3350, unlike the more uniform droplet population observed without PEG.

PEG typically influences protein condensation through excluded volume interactions or co-condensation mechanisms, which can modify material properties and potentially disrupt the phase behavior of biomolecules52,53. Assuming PEG3350 acts as an inert crowding agent, its occupation of solvent volume is expected to reduce the space available for macromolecules, increasing their effective concentration and lowering the phase separation threshold. However, we observed that the presence of PEG3350 resulted in smaller droplets with altered morphology (Fig. 3A and B). Thus, we hypothesized that PEG3350 might have deformed DDX3X droplets by direct interactions with the protein, leading to the observed non-spherical shapes.

Additionally, we comparatively studied the condensation of wild-type DDX3X-mCherry (Fig. 4A) and its neurodevelopmental disorder-linked mutant R376C (Fig. 4B) over time. The R376C mutant was shown to assemble gel-like stress granules in SH-SY5Y cells51. Thus, it is a good case-study for the analysis of morphological aspects of protein phase transition. We observed that DDX3X R376C forms small, spherical droplets in the first few minutes of incubation at room temperature but soon begins to aggregate forming elongated shapes as compared to expanding spherical droplets observed for the wild-type protein (Fig. 4A and C).

DDX3X R376C forms elongated condensates. (A and B) Representative diagrams of the condensation process of wild-type (WT) (A) and R376C (B) DDX3X. Raw images of WT condensates over time are depicted in the first raw. Below, the median values of descriptors: intensity, area, roundness, circularity, eccentricity, aspect ratio, and solidity are represented in a color map. (C) Representative fluorescence with respective brightfield images of LLPS assays over time of DDX3X WT and R376C. Scale bar: 10 µm.

Importantly, the partition coefficient is an objective descriptor for comparatively analyze both DDX3X WT and R376C phase separation. In a time-series experiment with both DD3X WT and R376C, the partition coefficient is initially equivalent until around 3 min incubation (Fig. 5A). It can be interpreted that both proteins have initiated LLPS, with most of droplets sharing similar area measurement (Fig. 4A and B), and equivalent partition coefficient (Fig. 5A) at 3 min incubation. However, a distinct and informative distribution emerges after 15 min incubation (Figs. 4A–B and 5A). DDX3X WT droplets coalesce over time leading to an increase in both partition coefficient and area measurements (Figs. 4A and 5A). The concentration of protein inside the R376C mutant condensates does not significantly increase over time, as indicated by the partition coefficient measure over time despite the area increment (Figs. 4B and 5A). The distribution of fractal dimension values (Fig. 5B) of DDX3X WT droplets shows most of droplets around 1, evidencing regular shapes, while the R376 mutant shows a tendency to increase more irregular, aggregated forms, with a positively skewed distribution of fractal dimension values.

Statistical analysis of DDX3X condensations dynamics. (A) Correlation of partition coefficient and droplet area after 3 and 15 min of incubation. WT DDX3X increases correlation when compared to the R376C mutant protein. (B) Fractal dimension after 60 min of incubation depicting a larger dispersion in mutant. (C) Principal component analysis (PCA) of morphological descriptors. The contribution of each descriptor for explaining the data variance is shown below in a color map. Hot colors represent a positive component while cold colors represent a negative component. The explained variance contribution of each component is shown in a bar graph. (D) Distribution of the same descriptor values over time as violin plots. (E) Scatter plots depicting roundness versus circularity after 3- and 15-min incubation. Blue = WT and red = R376C.

A principal component analysis (PCA) of the extracted shape descriptors indicated that clusters of DDX3X WT and R376C condensates share some features, although the mutant protein condensates are displaced to the first (top right) quadrant (Fig. 5C) due to high positive correlation with eccentricity and aspect ratio variables (Fig. 5C). Area and convex area descriptors are positive to PC1 and negative to PC2, thus being responsible for the fourth (bottom-right) quadrant, which contributes to grouping of the WT and R376C mutant condensates. However, the ratio between these last two variables, known as solidity, is stronger to separate both WT and R376C classes (Fig. 5C), with negative correlation in both PC1 and PC2.

After a few minutes of incubation at room temperature, there is a clear separation in shape between WT and R376C mutant condensates (Fig. 5A–C). On the one hand, an analysis of the aspect ratio distributions (Fig. 5D) shows that the WT condensates tend to aspect ratio values close to 1 over time, which indicates formation of a circular shape. The median aspect ratio of the R376C condensates, however, increases over time, reaching a value around 5 after 60 min incubation (Fig. 5D), which indicates elongated forms. Eccentricity distribution (Fig. 5D) analysis over time corroborates these results, showing an evident increase in the median value for the mutant in comparison with the WT condensates. The solidity descriptor (Fig. 5D), on the other hand, is more sensitive to morphological roughness. We observed that the solidity is stable around 0.8–1, indicating that the circular shape continues over time for the WT condensates, while the area of the WT condensates increases (Fig. 5D) due to coalescence. Instead, solidity decreases to a median around 0.4 for R376C condensates, indicating non-circular shapes of the elongated condensates due to aggregation of small droplets.

Furthermore, circularity values become more skewed over time for mutant condensates as compared to the WT ones. The roundness descriptor distribution is highly skewed for both WT and mutant condensates under all conditions. To illustrate the use of these descriptors in the study of protein condensation, we proceeded with a close analysis of the scatter plot of roundness against circularity (Fig. 5E) for the WT and mutant condensates at 3- and 15-min incubation. These results corroborate the results obtained based on the aspect ratio, eccentricity and solidity descriptors showing that both proteins assemble spherical condensates in the first few minutes and that R376C become more elongated yet less round (i.e. containing fewer round edges).

To highlight the complex shapes of the DDX3X WT and mutant condensates over time, we analyzed the behavior of the Euler characteristic number (Fig. 6A and B). Most of the WT droplets show almost no topological complexity over time, with Euler characteristic number around 1. Comparatively, the R376C mutant condensates show values distinct from 1 indicating higher complexity. We selected some examples of condensate morphologies from the Euler characteristic number distribution over time and exhibited their respective images (Fig. 6C) as representative images of the high complexity distribution of the R376C condensates formed from aggregation of small droplets.

Euler characteristic number of DDX3X condensates. (A and B) Distribution of Euler characteristic number over time for wild-type (A) and R376C mutated (B) DDX3X condensates over time. (C) Representative images of segmented DDX3X R376C condensates selected from the Euler characteristic number distribution over time.

Effect of pixel number in the calculation of condensate shape descriptors

The algorithms used to calculate shape descriptors can be sensitive to the amount of information available from each condensate image. This is largely important in experiments with the objective of following droplet growth over time. To define a round shape based on the circularity descriptor, for example, our analysis suggests that at least 20 × 20 pixels are necessary (Fig. 7A and B). It is evident that circularity is one of the most sensitive shape descriptors. We observed that small objects represented by less than 20 × 20 pixels can be mistakenly calculated giving values over 1, which is expected for a perfect circle. Regardless of the physical shape of a condensate, the employed algorithm calculates the circularity descriptor for objects with at least 4 × 4 pixels (Fig. 7A and B), which can lead to errors due to missing information.

Analysis of the effective pixel number for the calculation of morphological descriptors. (A) Scatter plot of circularity values versus major axis size (in pixel). (B) Representative images of segmented condensates based on the distribution of circularity values versus major axis size. (C) Scatter plot of roundness values versus major axis size (in pixel). (D) Representative images of segmented condensates based on the distribution of roundness values versus major axis size. (E–G) Scatter plots depicting eccentricity (E), aspect ratio (F) or solidity (G) versus major axis size (in pixel).

On the other hand, the roundness descriptor is less sensitive to a small number of pixels, representing an interesting alternative when the droplet is small. This is an instance that usually happens in the beginning of the condensation process in a time series experiment. Figure 7C and D demonstrates that roundness is a reliable parameter to describe an object represented by at least 9 × 9 pixels. Finally, eccentricity (Fig. 7E), aspect ratio (Fig. 7F) and solidity (Fig. 7G) descriptors are hardly affected by pixel number.

Discussion

The analysis of liquid–liquid phase-separated droplets under different physicochemical conditions is critical to understanding the biophysical properties that govern the behavior of biomolecular condensates. Traditionally, image-based methods are highly manual and time-consuming, limiting the capacity to analyze large samples. Here, we developed a computational pipeline based on Python open-source platforms and a well-validated library for image analysis, namely scikit-image46, making it freely available. Furthermore, by using an interactive interface in the Jupyter Lab platform31, we created a user-friendly environment that allowed us to fine tune the image processing steps to accommodate distinct images and/or image contrast. The workflow can easily operate in large datasets, which is suitable for high throughput assays. Additionally, the data path and logic used to identify files and metadata can be adjusted directly in the code following our supporting commentaries. The workflow input is fluorescence images of the condensates of interest accompanied by metadata provided by the user. Our proposed analytical pipeline can accommodate both desktop and High-Performance Computing (HPC) for CPU parallel multiprocessing to increase the number of images to be analyzed.

Ideally, fluorescent recombinant proteins are employed to maintain a controlled environment for intensity comparison if necessary. Nonetheless, proteins can be conjugated with a fluorophore in-vitro. There is no limitation for the choice of a fluorophore, respecting the microscope optical setup. Although confocal models are preferred to avoid out-of-focus photons at the detector, full-field imaging techniques can be used equally. Running Z-stack imaging to capture droplet images from different heights at the liquid column can be a good practice, albeit fast Brownian movement can induce motion artifacts affecting image resolution.

Key morphological descriptors of all protein droplets in an LLPS experiment are extracted, providing valuable insights into the structure and dynamics of biomolecular condensates, which are difficult to assess through traditional qualitative observation. Protocols are available for the analysis of microscopy data from high-throughput LLPS assays54. However, they are largely based on fluorescence intensity measurement. Here, we use several morphological descriptors together with fluorescence intensity quantification that can be merged with information from several experimental variables such as protein concentration, ionic strength, ligand type and concentration, presence of crowding agents, among others, to fill the LLPS space while also gaining insight into the potential molecular mechanism involved.

Additionally, the pipeline includes calculation of the partition coefficient to objectively infer how much of the protein undergoes LLPS and accumulates into the droplets, or if the protein partition into the droplets is dependent or not on the total protein concentration55. This metric has been traditionally used56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63, also being incorporated in another computation approaches for LLPS studies64,65,66,67. Nonetheless, attention must be given to the definition of the background as the fluorescence signal can scatter from the droplet and be computed erroneously as background, causing a bias in this value. To prevent this issue, we recommend using an erosion of at least 4 pixels from the droplets mask. Importantly, this value should be optimized according to a given microscopy optical setup, which could be easily performed using the “show plot” option in the main droplet analysis tool. Finally, we also suggest using median instead of mean values to prevent artifacts caused by outlier pixels.

To validate our pipeline, we characterized the phase separation of the neurodevelopmental protein DDX3X in the presence of crowding agent or upon mutation. We chose to study the effect of a neurodevelopmental disorder-associated mutation, R376C, on DDX3X phase behavior providing insights into the molecular mechanisms of protein aggregation that underly the physiopathology of the disease. Our assay recapitulates the characteristic differential partitioning behavior of DDX3X protein during LLPS, with notable differences between WT and R376C mutant variants. At the 3-min timepoint, both WT and R376C DDX3X proteins exhibit similar initial phase separation properties. The comparable partition coefficient-to-area relationship suggest that both variants initially undergo LLPS with equivalent probability, forming condensates of similar size and protein concentration. This initial similarity indicates that the R376C mutation does not significantly impair the early nucleation and formation of protein condensates. The WT protein condensates then coalesce, maintaining their sphericity, and the local protein concentration increases, resulting in higher fluorescence intensity within these larger condensates. In contrast, the R376C mutant transitions to an aggregated state, preventing efficient protein redistribution, resulting in condensates that maintain similar fluorescence intensities despite increasing in size. The partition coefficient provides an objective quantification of protein enrichment within condensates relative to the surrounding dilute phase68. The observed differences in partition coefficient-to-area relationships between WT and R376C represent meaningful differences in their phase separation behaviors. It corroborates the observed R376C-rich stress granules in SH-SY5Y cells which transition from liquid-like to more solid-like condensates over time, as validated by FRAP studies51.

Importance of morphological descriptors for the analysis of biomolecular condensation

Morphological descriptors, such as area, convex area, perimeter, circularity, roundness, eccentricity, solidity, Euler characteristic number and fractal dimension are essential for quantifying the structure of phase-separated condensates. Each descriptor captures distinct and even subtle aspects of droplet shape and organization, allowing us to differentiate between droplets among groups that appear similar to the naked eye but have fundamentally different properties, which are characteristic of their biophysical properties.

The structural characteristics of droplets, defined by their morphological descriptors, provide essential clues about their formation mechanisms and functional relevance. For example, area, circularity and eccentricity are often used as particularly important for assessing the degree of droplet sphericity or elongation69,70. These parameters provide information on how droplets maintain or lose their circular integrity over time or in response to external stimuli, such as presence of crowding agents, or any other physicochemical parameter. In fact, DDX3X WT droplets showed circularity and roundness values close to 1, evidencing their spherical shape. However, the presence of PEG3350 led to the formation of non-spherical droplets, based on decreasing roundness values. Since PEG3350 led to smaller droplets with altered morphology, it is possible that it deformed the protein droplets through direct interactions with the protein.

Droplets with higher circularity and roundness tend to exhibit stable, energetically favorable configurations, while elongated or irregular droplets (with lower circularity and roundness, and higher eccentricity) might indicate underlying biophysical changes such as fusion, fission, internal restructuring or phase transition from a liquid to a solid. Eccentricity and aspect ratio help distinguish between spherical droplets and more elongated ones, potentially shedding light on the mechanical forces at play within the phase-separated regions. These shape-based descriptors are especially useful in tracking the progression of LLPS over time, where initial spherical droplets may evolve into more complex shapes as they mature, fuse, or fragment. However, confirming a possible phase transition from liquid to solid typically requires an orthogonal validation method, such as FRAP17 and XPCS25,26.

Additionally, the solidity descriptor, which represents the ratio between the area and the convex area descriptors, reflects how closely the droplet boundary approximates a convex shape, which is crucial for identifying deformations or irregularities on the droplet surface. Low solidity values can indicate complex phase behavior, such as partial coalescence or the emergence of substructures within the droplets, which could signal interactions between internal components or phase transitions.

The Euler characteristic number further adds to this by quantifying the topological complexity and connectivity of droplets. The Euler characteristic number is derived from the relationship between vertices, edges, and faces of the shape. A value of 1 indicates a single connected component with no holes. A higher or lower Euler characteristic number indicates changes in connectivity, such as the addition of holes or branches, which increase a shape’s complexity71. In binary images, the Euler characteristic number is calculated using pixel connectivity, helping to quantify the topological structure and changes in the shape (e.g., transitions from solid to porous structures)72.

As a biomolecular condensate descriptor, the Euler characteristic number emerges as a strong candidate to retrieve shape variations, with values around 1 meaning droplets largely intact and without internal voids, while lower or higher values indicate the presence of holes, cavities and branching. The appearance of these topological features could signify internal phase separation within the droplet itself, highlighting critical structural transitions that may be functionally relevant in biological processes. The Euler characteristic number was particularly important for the complete characterization of DX3X R376C condensates that were shown to aggregate, showing Euler characteristic number below 1 over time.

Furthermore, we implemented fractal dimension calculation, a concept largely used in structural biology to investigate shape complexity more objectively73,74, since it is sensitive to the ratio of the change in detail to the change in scale, identifying subtle variations in fractal scale. Besides being useful to describe shapes, it is one of the best options to unveil variation in branching patterns which might occur during aggregation of proteins with low LLPS likelihood54. The fractal dimension is also potentially useful to point out the branching behavior in a fibrillation event on the surface of the condensate14. This behavior awaits further investigation.

Statistical analysis of condensate descriptors

The morphological descriptor distribution profile is critical when studying biomolecular condensation. Conventional descriptive statistics such as mean and standard deviation are predicated on the assumption of symmetry and adherence to a Gaussian (normal) distribution. As a result, they may fail to adequately capture and summarize key parameters when the distribution exhibits significant asymmetry or deviates from normality. Alternative approaches, such as analysis of skewness, kurtosis, or robust measures like the median and interquartile range, are better suited for analyzing non-symmetric distributions observed for most shape descriptors. They quantify the degree of distortion from the symmetrical curve (i.e. normal distribution). This kind of analysis may shed light on the effects in an LLPS assay according to distinct experimental set up. Importantly, this information can be critical for identifying unique or rare morphological traits. By analyzing skewness and kurtosis together, it is possible to have a more comprehensive understanding of the shape distribution of a dataset. Particularly, if a dataset has high positive skewness and high kurtosis, it indicates that the shapes are not only asymmetric but also have significant outliers.

Besides the descriptive statistical analysis of individual descriptors and multiple correlations, PCA is a powerful tool in morphological analysis, especially when dealing with multiparametric datasets that contain multiple, possibly correlated, morphological descriptors and physicochemical conditions75,76,77. A high dimensional dataset that contains multiple features describing shape characteristics (e.g., length, width, aspect ratio, compactness) usually has inherent patterns, such as clusters or gradients of shapes, that become challenging to visualize or analyze directly. PCA reduces the number of variables by identifying the directions (principal components) in the droplet shape dataset that captures maximum variance. In the context of condensate analysis, these components represent the most significant shape variations across the droplet population, unveiling the most informative aspects of morphology without losing significant information, with each principal component representing a linear combination of the original shape measurements. The first component might capture the overall size variation (usually prevented by data standardization), while subsequent components might represent more subtle shape characteristics like elongation or surface irregularities. By projecting original data onto these principal components, PCA reveals natural groupings or clusters of droplet condensates with similar morphological characteristics, reflecting different physical conditions, composition, or phase states of the condensates. This facilitates the identification of distinct condensate populations that might be difficult to detect in the original high-dimensional space. Finally, the plot reveals correlations between original shape parameters. The loading plot visualizes how the original variables contribute to each principal component. When parameters cluster together in a loading plot of phase-separated biomolecules data, this indicates that these variables have a strong positive correlation with each other in the original dataset. If several of these parameters appear clustered together in a loading plot, it indicates they tend to change together across the biomolecular condensates dataset representing certain physicochemical condition of interest. For instance, if area and partition coefficient cluster together, larger condensates generally contain more protein.

In the proposed analytical pipeline, we introduce an interactive and easy-to-use functionality of PCA, so that users can interact with data in real-time, displaying the relevant features and clustering according to morphological descriptors and experimental groupings. Data normalization may be critical in PCA based in variances and distances to ensure all features in morphological analysis contribute equally and avoid biases caused by differences in measurements scales. Thus, we implemented Python functions to normalize or standardize the data before analysis. It is important to consider the impact of these procedures to avoid bias. Absolute maximum method is helpful when we want to retain the original structure of the data but need it on a smaller scale, such as when we want to reduce the impact of extreme outliers. Minimum and maximum scaling is ideal when all features need to be within the same range for interpretability or when the dataset contains features with diverse ranges but does not have extreme outliers, as outliers can disproportionately affect the min–max scaling. Standardization is essential when the data follows a normal distribution, making data comparable on a relative scale, reducing the effect of outliers.

As a result, the PCA plots retrieve information of the shape variation predominant pattern, with closely positioned condensates sharing similar morphological characteristics. The eigenvectors indicate which original shape measurements contribute most significantly to each principal component. This helps identify which morphological features are most discriminative for different condensate populations. Additionally, the eigenvalues associated with each component, visualized as a scree plot, show the percentage of total variance explained by each component and can be used to determine how many components are needed to adequately represent your condensate dataset.

In the study of DDX3X condensation, PCA helped to distinguish between condensates rich in wild-type or mutant protein. By examining the PCA biplot, it is easy to isolate the most important features responsible for clusterization, for instance eccentricity and aspect ratio. Furthermore, solidity, a ratio between area and convex area, is highlighted and has an important impact on the biophysical behavior over the time course of DDX3X condensation/aggregation. With less than 3 min passed since the beginning of the experiment, both WT and R376C small droplets initiate the coalescence, without noticeable shape variation. By 3 min, the solidity of mutant shows that the droplet shape becomes less convex. Simultaneously, the area descriptor indicates that WT droplets are expanding. It can be interpreted as strong evidence that the mutant R376C protein forms aggregates.

Relevance of the morphological analysis of biomolecular condensates to biological systems

Accurately quantifying these morphological descriptors not only enhances our understanding of LLPS in vitro but also provides a framework for studying condensates in vivo. Many cellular functions are regulated by phase-separated biomolecular condensates that must maintain precise morphologies to carry out their roles effectively. For instance, the formation of stress granules, P-bodies, and nucleoli reflects the fine balance of droplet size, shape, and internal composition. The ability to systematically measure and compare these features under different biological conditions (e.g., varying protein concentrations, mutations, or stress factors) opens avenues for dissecting the mechanisms driving LLPS.

By automating the measurement of these descriptors, our computational pipeline provides a reproducible and high-throughput method for characterizing droplet morphologies. This overcomes the limitations of manual analysis, which can introduce bias and variability. Moreover, this pipeline facilitates comparative studies across different experimental conditions, allowing us to investigate how various parameters, such as protein mutations or environmental changes, impact LLPS dynamics and droplet structure.

Image resolution as a major limitation

A critical aspect of this pipeline for quantifying shape descriptors is due to the nature of the digital images approach: the number of pixels in each object. In the case of LLPS experiments, the droplets are small objects with up to a few micrometers in diameter. The optical setup must be optimized to increase magnification and/or reduce binning at the detector. This will reduce the effective physical pixel size in the digital image, thus increasing the number of pixels that compose a single object. Otherwise, several limitations will hamper data analysis. Shape descriptors are typically sensitive to the level of detail in the image.

Low resolution images capture fewer pixels per object, leading to a loss of critical geometric details. This becomes especially problematic for shape descriptors that rely on precise boundary and inner structure of an object. In under-represented objects, the edges are often poorly defined or even nonexistent. The loss of detail makes it hard to distinguish between subtle differences in condensate morphology. For instance, small deviations in the shape of an object (e.g., the difference between a circle and an ellipse) might not be captured well when the resolution is too low. In the worst cases, a small number of pixels can lead to a square shape.

Some descriptors are more sensitive to low object definition. For instance, circularity just becomes confident with objects around 20 × 20 pixels. Conversely, the roundness descriptor is less sensitive to small number of pixels, representing an interesting alternative. Eccentricity, aspect ratio and solidity descriptors are hardly affected by pixel number. Nonetheless, it is critical to retain most of the descriptors for a confident statistical analysis and, if it is unavoidable to work with low resolution images, these conditions must be evaluated case-by-case, filtering out the poorly defined objects.

The approach presented here demonstrates the advantages of the morphological descriptors extracted from LLPS droplets in comparative experiments of spatiotemporally-resolved protein condensation. The descriptors and fluorescence intensity of every single droplet proved to be powerful means of quantitatively characterizing condensates physical properties, even for users with limited experience in the field. It is worth noting that shape descriptors alone might not be fully capable of distinguishing between different biomolecular states. It might be necessary to integrate morphological analysis of condensates with complementary biophysical characterization, including atomic force microscopy (AFM), dynamic or multi-angle light scattering (DLS or MALS, respectively), fluorescence and circular dichroism spectroscopies, and NMR experiments to provide a full picture of the condensation and/or aggregation processes of macromolecular biomolecules. However, understanding the key shape metrics of condensates under different physicochemical conditions is an important proxy to unraveling the biophysical principles that govern biomolecular phase separation and its implications in biological function and disease. The proposed computational pipeline enables rapid, accurate, and unbiased analysis, providing a valuable tool for advancing the study of protein phase separation and its biological relevance.

While several open-source tools such as FIJI78 and CellProfiler79 can perform similar image analysis69, our platform offers enhanced flexibility for integrating both imaging and statistical analysis, making it accessible even to researchers without programming expertise. Users can import customized experimental datasets and images in various file formats regardless of the microscopy acquisition method used. Our solution features an interactive image segmentation interface that allows precise adjustments and shape descriptor calculations. It is complemented by advanced statistical analyses of descriptors including conventional measurements such as background and droplet intensities, partition coefficient, area, circularity and roundness and more advanced descriptors such as Euler number and fractal dimension for fine quantification of droplets’ irregularities. Besides conventional statistical descriptors, we also implemented measurements of data distribution asymmetry, interactive multivariate PCA and correlations of each descriptor, through an intuitive graphical interface. A distinguishing aspect of our system is its innovative tool for generating interactive phase maps with user-friendly controls. Additionally, we provide our platform as a Singularity container, enabling seamless scaling to high-performance computing environments. This comprehensive pipeline is valuable for LLPS studies ranging from limited confocal or wide-field microscopy images to extensive datasets from high-throughput screening experiments.

Material and methods

Heterologous expression and purification of DDX3X-mCherry, and LLPS assays.

As an example of application, we investigated the condensation of the RNA helicase protein DDX3X in the presence of crowding agents. Firstly, DDX3X-mCherry expression and purification followed the protocol described by Shen and collaborators30, with modifications. Briefly, the recombinant protein was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) RPIL by IPTG induction and protein purification followed affinity chromatography and gel filtration steps. DDX3X-mCherry samples were snap-frozen at 100 μM final concentration in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.5, 500 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol and 2 mM DTT. The wild-type DDX3X-mCherry phase diagram was then obtained by incubating different concentrations (1.25–10 µM) of the protein at room temperature (~ 24 °C) for up to 75 min in a final buffer containing 25 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.5, 75 mM NaCl, 0.2 mM DTT and 2% glycerol, in the presence of different concentrations (0–5%) of crowding agent PEG3350. Each mixture had a final volume of 20 μL and was manually pipetted into a 384-well plate. The DDX3X-mCherry R376C plasmid was obtained by site-directed mutagenesis30,51. We analyzed DDX3X-mCherry R376C mutant condensation under the same buffer condition, in the absence of crowding agent.

Hich content fluorescence microscopy

The Operetta CLS high-content analysis system (PerkinElmer) was used to scan each well with a 40X WD dry objective. Micrographs were collected at 4 regions of interest (ROI) of 1024 × 1360 pixels2, with a pixel size of pixel size of 0.2486 × 0.2486 µm2, randomly selected from each well at 3 Z-positions, at 1-min steps.

The computational pipeline

Our proposed computational pipeline for the analysis of biomolecular condensates was implemented in Python27 using the open-source libraries. For image processing and quantification, the scikKit-Image library was used46. Additional PoreSpy library47 was used through the function ‘boxcount’, over the image of each droplet, to return the box size and respective number so a linear model if fit and slope is interpreted as the fractal dimension. We further implemented the pipeline in a Jupyter notebook80, which offers a web-based interactive interface for users to handle data visualization and exploratory analysis.

A specific folder structure for file storage is recommended, that allows the whole pipeline to run automatically: 1) “data” (images) separated in subfolders according to the experiment date; 2) “metadata” to store files containing details of the experiment and the map plate; 3) “output” to save the results, plots, images, etc. Fine description is included at the Git repository80. However, it is possible to use any custom file organization by adjusting the path logic in the script, following the commentaries.

The process is computed using parallelization in CPU cores to maximize efficiency. It detects available cores in standard desktops as well as in High Performance Computer (HPC) using job schedulers (e.g. SLURM). A metadata file in CSV format must be supplied by the user containing all the parameters necessary to LLPS analysis in columns, such as experiment date, replicate, protein type, protein concentration, among others, as well as the respective well number (e.g. “A3”). A sample file is provided at the repository and must include the date of the experiment and the plate well number in “date” and “well_plate” columns, respectively since these columns will be used to merge experiment data with the calculated morphological descriptors. Remaining columns can be renamed or deleted, or even additional columns can be included according to the variables in the experiment. The user can add as many parameters as necessary to describe their experiment. As an example, users can include protein name, protein concentration, specific mutation, salt type and concentration, secondary crowder agents, etc. In the Jupyter notebook interface an interactive filed will scan for all CSV file in the Metadata folder and list in a dropdown menu. Once selected, it is loaded automatically and displayed for easy inspection.

The output is organized in a Pandas81 dataframe capable of returning exploratory and descriptive statistics. Several statistical tools are available to explore and interact with data by creating plots, groups, filtering, etc., directly over the Pandas dataframe using Plotly library as backend. We include PCA tools for dimensionality reduction using scikit-learn library82 to facilitate pattern interpretation of the groups, with several menus and options to create the plot. It also includes 3 types of normalization. Absolute maximum divides by the maximum absolute values in the dataset bringing the values into a range between –1 and 1. Minimum and maximum scaling scales the data to a fixed range, typically [0, 1], by subtracting the minimum value from the value and dividing it by the difference of maximum and minimum values [i.e. (x−xmin)/(xmax−xmin)]. Standardization scales the data so that each feature has a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 by, for each value, subtracting the mean and dividing the result by the standard deviation.

Data availability

Our Jupyter lab interface with proposed computational pipeline is made available on GitLab repository (https://gitlab.com/murilo.carvalho/2024_llps_analysis.git) and the image dataset on Zenodo (doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14387077).

Code availability

All scripts necessary to run the pipeline are available as open source on GitLab (https://gitlab.com/murilo.carvalho/2024_llps_analysis.git ).

References

Hyman, A. A., Weber, C. A. & Jülicher, F. Liquid-liquid phase separation in biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 30, 39–58 (2014).

Alberti, S., Gladfelter, A. & Mittag, T. Considerations and challenges in studying liquid-liquid phase separation and biomolecular condensates. Cell 176, 419–434 (2019).

Hong, K., Song, D. & Jung, Y. Behavior control of membrane-less protein liquid condensates with metal ion-induced phase separation. Nat. Commun. 11, 5554 (2020).

Cochard, A. et al. RNA at the surface of phase-separated condensates impacts their size and number. Biophys. J. 121, 1675 (2022).

Dignon, G. L., Best, R. B. & Mittal, J. Biomolecular phase separation: from molecular driving forces to macroscopic properties. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 71, 53–75 (2020).

Brangwynne, C. P., Tompa, P. & Pappu, R. V. Polymer physics of intracellular phase transitions. Nat. Phys. 11, 899–904 (2015).

Ruff, K. M., Roberts, S., Chilkoti, A. & Pappu, R. V. Advances in understanding stimulus-responsive phase behavior of intrinsically disordered protein polymers. Phase Sep. Biol. Dis. 430, 4619–4635 (2018).

Cardinaux, F., Gibaud, T., Stradner, A. & Schurtenberger, P. Interplay between spinodal decomposition and glass formation in proteins exhibiting short-range attractions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 118301 (2007).

Gibaud, T. & Schurtenberger, P. A closer look at arrested spinodal decomposition in protein solutions. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 322201 (2009).

Fransson, S., Lorén, N., Altskär, A. & Hermansson, A.-M. Effect of confinement and kinetics on the morphology of phase separating gelatin-maltodextrin droplets. Biomacromol 10, 1446–1453 (2009).

Mazarakos, K., Prasad, R. & Zhou, H.-X. SpiDec: Computing binodals and interfacial tension of biomolecular condensates from simulations of spinodal decomposition. Front. Mol. Biosci. 9, 1021939 (2022).

Tollervey, F. et al. Cryo-Electron Tomography of Reconstituted Biomolecular Condensates. in Phase-Separated Biomolecular Condensates: Methods and Protocols (eds. Zhou, H.-X., Spille, J.-H. & Banerjee, P. R.) 297–324 (Springer US, New York, NY, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2663-4_15.

Babinchak, W. M. & Surewicz, W. K. Liquid-liquid phase separation and its mechanistic role in pathological protein aggregation. J. Mol. Biol. 432, 1910–1925 (2020).

Visser, B. S., Lipiński, W. P. & Spruijt, E. The role of biomolecular condensates in protein aggregation. Nat. Rev. Chem. 8, 686–700 (2024).

Biswas, S. et al. Molecular crowding accelerates aggregation of α-synuclein by altering its folding pathway. Eur. Biophys. J. 50, 59–67 (2021).

Ross, C. A. & Poirier, M. A. Protein aggregation and neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Med. 10, S10–S17 (2004).

Taylor, N. O., Wei, M.-T., Stone, H. A. & Brangwynne, C. P. Quantifying dynamics in phase-separated condensates using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching. Biophys. J. 117, 1285–1300 (2019).

Holland, J., Crabtree, M. D. & Nott, T. J. In Vitro Transition Temperature Measurement of Phase-Separating Proteins by Microscopy. In: Intrinsically Disordered Proteins: Methods and Protocols (eds. Kragelund, B. B. & Skriver, K.) 703–714 (Springer US, New York, NY, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-0524-0_36.

Xu, B. et al. Manganese promotes α-synuclein amyloid aggregation through the induction of protein phase transition. J. Biol. Chem. 298, 101469 (2022).

Wu, Y. et al. RNA-induced liquid phase separation of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein facilitates NF-κB hyper-activation and inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 6, 167 (2021).

Ziaunys, M. et al. Diverse effects of fluorescent labels on alpha-synuclein condensate formation during liquid-liquid phase separation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 283, 137688 (2024).

Cinar, H. & Winter, R. The effects of cosolutes and crowding on the kinetics of protein condensate formation based on liquid–liquid phase separation: a pressure-jump relaxation study. Sci. Rep. 10, 17245 (2020).

Li, H.-W., McCloskey, M., He, Y. & Yeung, E. S. Real-time dynamics of label-free single mast cell granules revealed by differential interference contrast microscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 387, 63–69 (2007).

Bramham, J. E. & Golovanov, A. P. Temporal and spatial characterisation of protein liquid-liquid phase separation using NMR spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 13, 1767 (2022).

Perakis, F. & Gutt, C. Towards molecular movies with X-ray photon correlation spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 22, 19443–19453 (2020).

Berkeley, R. F., Kashefi, M. & Debelouchina, G. T. Real-time observation of structure and dynamics during the liquid-to-solid transition of FUS LC. Biophys. J. 120, 1276–1287 (2021).

Welcome to Python.org. Python.org https://www.python.org/ (2024).

Rindskopf, D. & Shiyko, M. Measures of dispersion, skewness and kurtosis. In: International Encyclopedia of Education (Third Edition) (eds. Peterson, P., Baker, E. & McGaw, B.) 267–273 (Elsevier, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.01344-0.

Rosa e Silva, I., Smetana, J. H. C. & de Oliveira, J. F. A comprehensive review on DDX3X liquid phase condensation in health and neurodevelopmental disorders. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 259, 129330 (2024).

Shen, H. et al. Sexually dimorphic RNA helicases DDX3X and DDX3Y differentially regulate RNA metabolism through phase separation. Mol. Cell 82, 2588-2603.e9 (2022).

Kluyver, T. et al. Jupyter Notebooks—a publishing format for reproducible computational workflows. In Positioning and Power in Academic Publishing: Players, Agents and Agendas 87–90 (IOS Press, 2016). https://doi.org/10.3233/978-1-61499-649-1-87.

Harris, C. R. et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 585, 357–362 (2020).

Pizer, S. M. et al. Adaptive histogram equalization and its variations. Comput. Vis. Graph. Image Process. 39, 355–368 (1987).

skimage.exposure — skimage 0.24.0 documentation. https://scikit-image.org/docs/stable/api/skimage.exposure.html#skimage.exposure.equalize_adapthist.

Non-local means denoising for preserving textures — skimage 0.24.0 documentation. https://scikit-image.org/docs/stable/auto_examples/filters/plot_nonlocal_means.html#.

Buades, A., Coll, B. & Morel, J.-M. A non-local algorithm for image denoising. In: 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05) vol. 2 60–65 (IEEE, San Diego, CA, USA, 2005).

Buades, A., Coll, B. & Morel, J.-M. Non-local means denoising. Image Process. Line 1, 208–212 (2011).

Froment, J. Parameter-free fast pixelwise non-local means denoising. Image Process. Line 4, 300–326 (2014).

Darbon, J. Cunha, A. Chan, T. F. Osher, S. & Jensen G. J. Fast nonlocal filtering applied to electron cryomicroscopy. In 2008 5th IEEE International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging: From Nano to Macro 1331–1334 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1109/ISBI.2008.4541250.

Unsharp masking — skimage 0.24.0 documentation. https://scikit-image.org/docs/stable/auto_examples/filters/plot_unsharp_mask.html.

Otsu, N. A threshold selection method from Gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 9, 62–66 (1979).

Fiorio, C. & Gustedt, J. Two linear time Union-Find strategies for image processing. Theor. Comput. Sci. 154, 165–181 (1996).

Wu, K., Otoo, E. & Shoshani, A. Optimizing connected component labeling algorithms. (2005).

Interactive figures—Matplotlib 3.9.2 documentation. https://matplotlib.org/stable/users/explain/figure/interactive.html#jupyter-notebooks-jupyterlab.

matplotlib/ipympl. Matplotlib Developers (2024).

van der Walt, S. et al. scikit-image: Image processing in Python. PeerJ 2, e453 (2014).

Gostick, J. T. et al. PoreSpy: A python toolkit for quantitative analysis of porous media images. J. Open Source Softw. 4, 1296 (2019).

Mckinney, W. Data structures for statistical computing in python. Scipy https://doi.org/10.25080/Majora-92bf1922-00a (2010).

R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/.

Plotly Technologies Inc. Collaborative data science. https://plot.ly/ (2015).

de Castro Fonseca, M. et al. Molecular and cellular basis of hyperassembly and protein aggregation driven by a rare pathogenic mutation in DDX3X. iScience 24, 102841 (2021).

André, A. A. M., Yewdall, N. A. & Spruijt, E. Crowding-induced phase separation and gelling by co-condensation of PEG in NPM1-rRNA condensates. Biophys. J. 122, 397–407 (2023).

Brzezinski, M. et al. Protein-specific crowding accelerates aging in protein condensates. Biomacromol 26, 2060–2075 (2025).

Li, Y., Gu, J., Liu, C. & Li, D. A high-throughput method for exploring the parameter space of protein liquid-liquid phase separation. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 3, 100764 (2022).

Hosamane, N., Hartman, M. & Dubach, J. M. Clarifying misconceptions of biomolecular condensate formation. 2024.07.17.603945 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.07.17.603945 (2024).

Shil, S., Tsuruta, M., Kawauchi, K. & Miyoshi, D. Biomolecular liquid-liquid phase separation for biotechnology. Biotech 12, 26 (2023).

Iqbal, M. et al. Aqueous two-phase system (ATPS): an overview and advances in its applications. Biol. Proced. Online 18, 18 (2016).

Diamond, A. D. & Hsu, J. T. Aqueous two-phase systems for biomolecule separation. In Bioseparation (ed. Tsao, G. T.) 89–135 (Springer, NY, 1992). https://doi.org/10.1007/BFb0046198.

Albertsson, P.-Å. Partition of cell particles and macromolecules in polymer two-phase systems. In: Advances in Protein Chemistry (eds. Anfinsen, C. B., Edsall, J. T. & Richards, F. M.) vol. 24, 309–341 (Academic Press, 1970).

Jia, T. Z. & Fraccia, T. P. Liquid crystal peptide/DNA coacervates in the context of prebiotic molecular evolution. Crystals 10, 964 (2020).

Frankel, E. A., Bevilacqua, P. C. & Keating, C. D. Polyamine/nucleotide coacervates provide strong compartmentalization of Mg2+, nucleotides, and RNA. Langmuir 32, 2041–2049 (2016).

Jia, T. Z., Hentrich, C. & Szostak, J. W. Rapid RNA exchange in aqueous two-phase system and coacervate droplets. Orig. Life Evol. Biospheres 44, 1–12 (2014).

Keating, C. D. Aqueous phase separation as a possible route to compartmentalization of biological molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 2114–2124 (2012).

Mitrea, D. M. et al. Methods for physical characterization of phase-separated bodies and membrane-less organelles. J. Mol. Biol. 430, 4773–4805 (2018).

Riback, J. A. et al. Composition-dependent thermodynamics of intracellular phase separation. Nature 581, 209–214 (2020).

Bergsma, T. et al. Imaging-based quantitative assessment of biomolecular condensates in vitro and in cells. J. Biol. Chem. 301, 108130 (2025).

Baggett, D. W. et al. An image analysis pipeline for quantifying the features of fluorescently-labeled biomolecular condensates in cells. Front. Bioinforma. 2, 897238 (2022).

Frontiers | An Image Analysis Pipeline for Quantifying the Features of Fluorescently-Labeled Biomolecular Condensates in Cells. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/bioinformatics/articles/https://doi.org/10.3389/fbinf.2022.897238/full.

Sanka, I., Bartkova, S., Pata, P., Smolander, O.-P. & Scheler, O. Investigation of different free image analysis software for high-throughput droplet detection. ACS Omega 6, 22625–22634 (2021).

Dixit, S. S., Pincus, A., Guo, B. & Faris, G. W. Droplet shape analysis and permeability studies in droplet lipid bilayers. Langmuir 28, 7442–7451 (2012).

Ziou, D. & Allili, M. Generating cubical complexes from image data and computation of the Euler number. Pattern Recognit. Inf. Syst. 35, 2833–2839 (2002).

Humberto Sossa Azuela, J. et al. Alternative formulations to compute the binary shape Euler number. IET Comput. Vis. 8, 171–181 (2014).

Johansen, D., Trewhella, J. & Goldenberg, D. P. Fractal dimension of an intrinsically disordered protein: Small-angle X-ray scattering and computational study of the bacteriophage λ N protein. Protein Sci. 20, 1955–1970 (2011).

Todoroff, N. et al. Fractal dimensions of macromolecular structures. Mol. Inform. 33, 588–596 (2014).

Martinović, S. et al. Principal component analysis of morphological descriptors for monitoring surface defects induced by thermal shock. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 41, 423–429 (2021).

Pavlović, N. et al. Principal component analysis (PCA) of molecular descriptors for improving permeation through the blood-brain barrier of quercetin analogues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 192 (2024).

Greenacre, M. et al. Principal component analysis. Nat. Rev. Methods Primer 2, 1–21 (2022).

Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis | Nature Methods. https://www.nature.com/articles/nmeth.2019.

Stirling, D. R. et al. Cell profiler 4: Improvements in speed, utility and usability. BMC Bioinf. 22, 433 (2021).

2024_LLPS_analysis GitLab. GitLab https://gitlab.com/murilo.carvalho/2024_llps_analysis (2024).

pandas—Python Data Analysis Library. https://pandas.pydata.org/.

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Juliana de Oliveira for the support and helpful scientific discussions. We acknowledge Gustavo de Oliveira for technical support and Dr. Daniel Maragno Trindade for support with site-directed mutagenesis. We are grateful for core funding and access to core facilities, including the Protein Purification Laboratory, the Bioassays Laboratory and the High Performance Computing Cluster, provided by the Brazilian Biosciences National Laboratory (LNBio) at the Center for Research in Energy and Materials (CNPEM), a non-profit organization under the supervision of the Brazilian Ministry for Science, Technology, and Innovations (MCTI). The National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (grant number 407904/2023-9 to IRS; 404617/2023-9 to MC) partly supported this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C. and G.G. wrote the code with input from I.R.S. and V.Y.U.N. F.Z.B., R.R.O. and I.R.S. purified DDX3X-mCherry constructs, and performed L.L.P.S. assays. I.R.S. and M.C. wrote the manuscript. I.R.S. and M.C. coordinated the project. All authors contributed to the reviewing and editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions