Abstract

Research on group singing has demonstrated numerous benefits to wellbeing including boosts in mood, increases in social bonding, and reductions in stress. These benefits can be achieved by individuals with Parkinson’s disease (PD), a group that is especially at risk for social isolation given the typical decline in mobility and communication that accompanies neuromotor degeneration. Several mechanisms of action have been proposed to explain the benefits to wellbeing, with one prominent hypothesis emphasizing that interpersonal movement synchrony enhances feelings of social bonding. In the current study, we explore this hypothesis by comparing group singing to yoga, another popular activity among people living with PD that confers a temporary boost in wellbeing. Critically, yoga tends to have low levels of interpersonal movement synchrony compared with group singing that requires precise temporal alignment and the shared goal of synchronization. Twenty individuals living with PD were recruited from pre-existing community programs: ten from a weekly choir, and ten from a weekly yoga class. We compared these activities through a biopsychosocial lens, including acute measurements of mood, social bonding, cortisol, and oxytocin before and after the group activity. The results revealed that while both activities enhanced mood and decreased cortisol, group singing was associated with greater overall social closeness and significant increases in oxytocin. Although the absence of demographic data represents a limitation, the findings nonetheless offer valuable insight into the potential of group singing to foster social bonds and enhance wellbeing, indicating interpersonal movement synchrony and the release of oxytocin as possible mechanisms driving this effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Individuals living with a neuromotor degenerative disease, especially those living with Parkinson’s Disease (PD), typically experience significant challenges to psychosocial wellbeing. Individuals with PD may experience social withdrawal due to mobility issues, speech difficulties, or the stigma associated with the condition. This withdrawal can exacerbate feelings of loneliness, social isolation, and depression1. Many individuals find strength and support through participation in PD specific programming where they can connect with others facing similar challenges. Group singing has gained popularity as a meaningful social activity that appears to have a remarkable capacity to improve vocal and communication outcomes in individuals living with PD2,3. Beyond these communication benefits, singing in a group setting may also offer unique psychosocial advantages; however, it remains unclear the degree to which these advantages stem from distinctive aspects of singing in a group, as opposed to general effects of participating in group activities.

What distinctive aspects of group singing might yield psychosocial advantages? One theoretical perspective suggests that some of the benefits of group singing may be attributable to cardiovascular engagement and controlled breathing4. However, these outcomes may be achievable when singing alone and thus, do not fully account for the social benefits5. Another theoretical perspective suggests that the benefits of group singing are due, in part, to an experience of cohesion caused by interpersonal movement synchrony between participants6. Group singing tends to lead to synchronization of head and torso movements as well as synchronization of muscles that underpin facial expressiveness, laryngeal control, and breathing7,8. Interpersonal movement synchrony has been shown to enhance social bonding as measured through self-report (e.g., belonging, rapport, similarity) and behavioral measures (e.g., cooperation, sharing)9,10,11,12,13,14.

An additional noteworthy aspect of group singing is that each singer is provided with live feedback on the extent of their movement synchrony through the matching of auditory in/output15. This is different from other group activities involving synchronous movement where a given individual is generally not able to observe all members at once. While group singing is not the only musical activity that gives rise to interpersonal movement synchrony (dancing or drumming also tend to elicit synchrony), it offers an accessible means of achieving it that can often be accomplished well into old age and even in people living with PD. According to this theoretical perspective, we hypothesize that group singing will offer additional social benefits compared to group activities lacking interpersonal movement synchrony.

Yoga enhances wellbeing

Yoga is another group activity widely practiced in the PD community that appears to give rise to feelings of wellbeing16,17,18. Yoga contains several characteristics in common with group singing, including cardiovascular engagement and controlled breathing. These characteristics may contribute to wellbeing by decreasing stress and orienting the nervous system towards parasympathetic dominance19. Moreover, both are social activities that involve movement in a group context. However, a critical differentiator between the two activities is the level of interpersonal movement synchrony involved. While movements between practitioners may be loosely coordinated in yoga, yoga invites a more self-centered perspective20, with movement primarily coordinated intra-personally and directed inward to the rhythm of one’s own breath, rather than synchronized interpersonally to a collective sense of rhythm. Although music is often present in yoga sessions, it tends to be more ambient, with less emphasis on the rhythmic properties of music known to drive movement synchrony21,22. In contrast, achieving synchronization is a central goal in group singing. Singing together requires precise temporal alignment across participants, fostering not only synchronized vocalizations but also spontaneous movements such as arm gestures or swaying. This distinction may have important implications for the social and neurophysiological effects of these activities. Considering the similar parasympathetic activation and positive effects on wellbeing, yet distinct levels of interpersonal synchrony, yoga serves as an elegant and naturalistic control condition to investigate the specific benefits of singing on wellbeing.

Potential biomarkers

Taking a biological perspective, researchers have identified several complex neurohormonal systems that may underpin the observed benefits of group singing23,24. In the current study, we have focused on two hormonal biomarkers: cortisol and oxytocin. First, cortisol, recognized as an important stress hormone linked to the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA), has robustly been shown to decrease as a result of both singing25,26 and yoga19,27. Second, oxytocin, is a neuropeptide that has been linked to social bonding and may underpin feelings of social closeness that arise during intimate social encounters in humans28,29 and non-human primates30. Two studies have found evidence in support of the release of oxytocin during group singing6,31. However, four other studies have reported opposite effects25,32,33,34. When interpreting these contradictory findings, it is important to consider how external stressors and other contextual factors may influence oxytocin levels. Two of these four studies yielding contradictory findings involved group singing at an elite level, which would involve stressors not present in community-based singing32,33. Although endocrine responses to group yoga have been a subject of interest in recent research35, to the best of our knowledge no studies have documented evidence consistent with release of oxytocin during group yoga.

The current study

In the current study, we investigated the extent to which the psychosocial benefits of group singing stem from distinctive aspects of singing in a group, rather than benefits that emerge from any enjoyable group activity. Specifically, we compared group singing to yoga, a group activity that has also been shown to provide acute boosts in wellbeing for people living with PD. While there are numerous factors that overlap between these two activities, they differ with respect to interpersonal movement synchrony: singing (high) and group yoga (low). Participants were recruited by leveraging existing PD community programs. We examined wellbeing outcomes using a biopsychosocial approach. This included self-reported mood, social closeness, and feelings of social connection with the group, as well as two potential hormonal biomarkers that are implicated in wellbeing effects, cortisol and oxytocin. Measures were collected at two time points, before and after the group activity. We hypothesized that acute mood boosts and changes in cortisol between the two groups would be comparable but we expected to see divergence in outcomes related to social bonding. More specifically, due to interpersonal movement synchrony, we expected group singing to demonstrate a stronger social bonding capacity as measured by social closeness and social connection with the group, as well as the release of oxytocin.

Methods

Participants

The study was approved by the Toronto Metropolitan University Ethics Board (2018–222). All experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines provided in the Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS2). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. In a quasi-experimental design, we recruited 20 participants from two pre-existing community programs for individuals living with PD: (1) group singing (n = 10, F = 5, mean age = 75.66 years, SD = 4.17) and (2) yoga (n = 10, F = 6, mean age = 68.3 years, SD = 5.18). All participants completed a cognitive assessment, the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). One participant from the singing group was removed from subsequent analysis for scoring lower than the predetermined eligibility threshold (< 26). Both groups had been meeting regularly for over a year prior to the study, and all participants were active members of their respective groups.

Design and procedure

In the singing group session, participants began with breathing exercises, followed by vocal warmups, and repertoire rehearsal, led by a music therapist with guitar accompaniment. Singing together within a structured external rhythm fostered high levels of movement synchrony. In the yoga session, participants also began with breathing exercises, followed by sequences of yoga poses and postures led by the yoga instructor. While ambient music played in the background, participants were instructed to move in alignment with their own breath, which limited opportunities for movement synchrony. There was no chanting in the yoga condition. Both sessions took place in the same local community centre, and participants had the opportunity to socialize before and after the activity. Data collection for all outcome variables occurred immediately before and after 45 min of group activity.

The study had one between-subjects factor (group: singing vs. yoga) and one within-subjects factor (time: pre vs. post). Dependent variables include mood (positive affect and negative affect), social closeness, social connection with the group, cortisol, and oxytocin. Mood was assessed using a brief mood questionnaire [PANAS36], which requires participants to report the extent to which they are currently experiencing 10 positively valanced items (such as enthusiastic and alert) and 10 negatively valanced items (such as distressed and upset). Social closeness was assessed using the Inclusion of Other in Self, a measure of perceived closeness between others by having participants select one of several increasingly overlapping circles that represent relationships [IOS37]. Social connection with the group was assessed using a brief questionnaire adapted from Wiltermuth & Heath14, where participants rated how much they Trust, Like, Feel similar to, and Feel connected to other group members using a Likert scale of 1 (not at all) to 7 (very much). Cortisol and Oxytocin were assessed using salivary assays. Saliva samples were collected using the passive drool method.

Salivary hormone assay

Cortisol saliva samples were subjected to a cortisol assay conducted in-house. The assay employed a standard 96-well plate enzyme-linked competitive immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit. Saliva sample preparations and processing adhered to the instructions outlined in the commercially available instruction manual provided by the ELISA kit. Samples were tested in duplicate to mitigate potential human pipetting error and an average concentration value was employed for statistical analyses. The lower limit of sensitivity for this test is 0.007 ug/dL. Oxytocin saliva samples were sent to an external laboratory to be subjected to an electrochemiluminescent assay for oxytocin. Samples were tested in triplicate to mitigate potential human pipetting error and the resulting average concentration value as employed for statistical analyses. The lower limit of sensitivity for this test is 8.0 pg/mL. Both the cortisol ELISA kit and the external oxytocin analysis were provided by Salimetrics (California, USA).

Statistical analysis

Before modelling, outliers were rejected based on a boxplot method wherein datapoints + /- 1.5 interquartile range were rejected. Given the between (group singing vs. yoga) and within (pre vs. post) subject design, there is inherent covariance (i.e., nesting) between observations which can affect model estimates and standard error38, skewing the results. Multilevel linear models (MLM) possess the capacity to control for this through the use of random-effects, which allow the intercept of the slope to vary based on grouping differences. Thus, all modeling was conducted using MLM using the lmer4 package39 in R.

The variables of interest included Group (group singing vs. yoga) and Time (pre vs. post). As these are both categorical variables, each was coded using contrast codes (i.e., 0 and 1) with one level used as a referent. References were set as pre (Time) and yoga (Group). Mood (Positive Affect and negative Affect), social closeness, feelings towards the group (IOS), cortisol, and oxytocin were modeled using separate MLMs. Each model contained a fixed-effects for Time and Group, as well as an interaction term in order to examine pre/post differences in each group. Simple slope analysis was used to examine how pre/post differences varied in each group, and if groups differed at each time point. It has been suggested that one-tail tests of significance are suitable in applied research contexts where there are priori predictions40. Based on our hypotheses, which predict specific increases/decreases on dependent measures, we used one-tailed tests of significance. Thus, p-values for each t-test were divided by two and alpha values for rejection of the null hypothesis were set at 0.05. For significant effect, effect sizes were provided using Cohen’s d.

Results

Positive affect

For visualization of positive affect trends see Fig. 1A. Results of a model on positive affect revealed a non-significant interaction between Time and Group, b = 1.62, t(17) = 0.68, p = 0.25. Inspection of the simple slopes revealed a significant main effect of Time for both yoga, b = 5.63, t(16) = 3.24, p = 0.002 and group singing, b = 4.01, t(16) = 2.34, p = 0.015. These results suggest that there was a significant increase of positive affect scores in the yoga group (b = 5.63) and the choir group (b = 4.01), following their respective group activity. The increase for group singing (d = 0.5) and yoga (d = 0.61) were both interpreted as medium effects sizes. There were no significant differences between groups before, b = − 0.69, t(27) = − 0.29, p = 0.38, or after, b = 2.32, t(27) = 0.1, p = 0.16, their respective group activity.

(A) Changes in positive affect between group singing and yoga groups. As shown, both groups showed a significant increase in positive affect scores following their respective group activity. Positive affect scores obtained before group activity did not differ significantly between groups. Error bars reflect bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals around the mean. *p <0.1 ** p <0.01 *** p < 0.001. (B) Changes in negative affect between group singing and yoga groups. As shown, there were no significant changes in negative affect following group activity in either group singing or yoga nor between groups before group activity (pre). Error bars reflect bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals around the mean. *p < 0.1 **p <0.01 *** p < 0.001.

Negative affect

For a visualization of the trends in negative affect, see Fig. 1B. Results of the model on negative affect scores revealed a non-significant interaction between Time and Group, b = 0.57, t(16) = 0.65, p = 0.26. Inspection of the simple slopes revealed no significant main effect of Time in either yoga group, b = − 0.2, t(16) = − 0.32, p = 0.37, or the group singing, b = − 0.77, t(16) = − 1.27, p = 0.11. There were no significant differences between groups before, b = 0.2, t(18) = − 0.21, p = 0.42, or after, b = 0.38, t(18) = − 0.38, p = 0.35, their respective activity.

Social closeness (IOS)

For a visualization of the trends in IOS, see Fig. 2A. The results of the model revealed a marginally significant interaction between Time and Group, b = 0.3, t(12) = 1.29, p = 0.1. Inspection of the simple slopes revealed no significant increase in IOS for the yoga group, b = 0.12, t(12) = 0.78, p = 0.22, following group activity, but a significant increase for the group singing, b = 0.43, t(12) = 2.5, p = 0.01. This suggests that there was a significant increase in IOS scores for group singing (b = 0.43), but no change observed following yoga. This increase of IOS scores in the group singing group (d = 0.58) was interpreted as a medium effect size. Lastly, IOS scores were shown to be significantly different between groups before, b = 0.93, t(14) = − 2.84, p = 0.005, and after, b = 0.63, t(14) = 1..92, p = 0.03, their respective group activity.

(A) Changes in IOS scores between group singing and yoga groups. As shown, there was a significant increase in IOS scores in the group singing condition. This increase was not shown in the yoga group, suggesting that this increase in IOS scores may be unique to group singing. Lastly, this figure also depicts significantly lower levels of IOS in the yoga group compared to the group singing prior to group activities (pre). Error bars reflect bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals around the mean. *p < 0.1 ** p <0.01 *** p < 0.001. (B) Changes in social connectedness across group singing and yoga. As shown, no significant changes were shown in either group singing or yoga group. Further, no differences were observed between groups before group activity (pre). Error bars reflect bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals around the mean. *p <0.1 ** p <0.01 *** p < 0.001.

Social connection

For visualization of the trends in social connectedness scores, see Fig. 2B. Results of the model revealed a non-significant interaction between Time and Group, b = 0.47, t(11) = 0.3, p = 0.77. Inspection of the simple slopes revealed no significant increase of social connectedness in the yoga group, b = − 0.14, t(11) = − 0.12, p = 0.45, or the group singing, b = 0.33, t(11) = 0.31, p = 0.38, following the group activity. There was no significant difference between groups before, b = 2.1, t(17) = 1.28, p = 0.11, or after, b = 1.62, t(17) = 1.01, p = 0.16, their respective group activity, although there was a trend for higher scores in the singing group both before and after the activity.

Cortisol

For visualization of trends in Cortisol levels, see Fig. 3A. Results of this model revealed a non-significant interaction between Time and Group, b = − 0.009, t(16) = − 0.19, p = 0.42. Inspection of the simple slopes revealed a marginally significant decrease of cortisol in the yoga group, b = − 0.05, t(15) = − 1.45, p = 0.08, and a significant decrease in group singing, b = − 0.06, t(15) = − 1.78, p = 0.04, following their group activity. This suggests that following the group activity there was a significant reduction in cortisol of 0.06 µg/dL for individuals in the singing group and a marginally significant reduction of 0.04 µg/d for individuals in the yoga group. These decreases in cortisol for the group singing (d = 0.41) and yoga (d = 0.35) are both interpreted as a small effect size. There were no differences between groups before, b = − 0.03, t(30) = − 0.83, p = 0.2, or after, b = 0.04, t(30) = 1.12, p = 0.13, their respective activity.

(A) Changes in cortisol levels between group singing and yoga groups. As shown, there was a significant reduction in cortisol following group singing. Further, although there was no statistical significant reduction in cortisol following yoga, there was a numeric trend towards a reduction in this group. There was no significant difference in cortisol levels between groups before activity (pre). Error bars reflect bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals around the mean. *p <0.1 ** p <0.01 *** p < 0.001. (B) Changes in oxytocin levels between group singing and yoga groups. As shown, there was a significant increase in levels of oxytocin in group singing following the activity, but no changes in the yoga group. Finally, there were significantly higher levels of oxytocin in the yoga group, compared to group singing, before group activity (pre). Error bars reflect bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals around the mean. *p <0.1 ** p <0.01 *** p < 0.001.

Oxytocin

For visualization of the trends in oxytocin levels, see Fig. 3B. Results of this model revealed a significant interaction between Time and Group, b = 7.05, t(12) = 1.75, p = 0.05. Inspection of the simple slopes revealed no significant increase in oxytocin in the yoga group, b = − 0.12, t(13) = − 0.04, p = 0.48, but a significant increase for the group singing group, b = 6.93, t(12) = 2.4, p = 0.015. This suggests that for group singing, there was a significant increase in oxytocin by 6.93 pg/ml following their activity, but no change observed following yoga. The increase in the singing group (d = 0.57) was interpreted as a medium effect size. There was a significant difference between the groups before their activity, b = − 5.71, t(23) = − 1.8, p = 0.04, but no significant difference after, b = − 1.33, t(24) = − 0.43, p = 0.33.

Discussion

In the current study, we aimed to determine to what extent psychosocial benefits of group singing arise from merely participating in an enjoyable group activity. We compared group singing with group yoga to investigate the theoretically derived role of interpersonal movement synchrony in wellbeing outcomes. Our findings showed that although both group activities boosted mood and decreased cortisol, only the group singing elicited increases in oxytocin, a key biomarker associated with social bonding. Consistent with these biomarker trends, the singing group elicited greater increases in social closeness, with higher levels reported overall compared to the yoga group. These effects suggest that group singing may possess an enhanced ability to foster close social bonds as compared to yoga. Although we expected to see a group difference in social connectedness, and the trend was in the anticipated direction, it did not reach statistical significance. This may be due to limited statistical power or lack of control over the naturally occurring nature of the groups, where factors such as varying group tenure and turnover could not be fully controlled.

The decreases in cortisol following both singing and yoga align with research suggesting that group activities reduce stress19,25,26,27. While our findings are consistent with some studies on singing and cortisol, they differ from others which found no singing-related changes in cortisol in a PD population [e.g., 3]. Similarly, although the increase in oxytocin for the singing group, but not yoga, adds to evidence linking group singing to oxytocin release6,31, other studies have reported no such effect25,32,33,34. One possible explanation for these discrepancies is the role of familiarity—neurohormonal responses may be influenced by the initial stress of a new environment, with both cortisol reductions and oxytocin increases becoming more likely to emerge as participants become more comfortable over time. It is also important to note that cortisol levels naturally decline over the course of the day following the initial rise over the cortisol awakening response (i.e., exhibit a diurnal pattern), which may contribute to observed decreases independent of the interventions. Additionally, the higher pre-activity oxytocin levels in the yoga group suggest a possible ceiling effect. These findings underscore the need for further research on neurohormonal responses to group activities, particularly as they emerge over time.

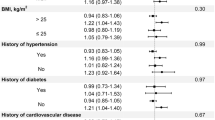

The study has a few limitations. Firstly, as a quasi-experimental design, participants were not randomly assigned to group activity, and future research should consider random assignment to limit possible selection bias. While the design aimed to capture the effects of two naturally occurring group activities (singing and yoga) in real-world settings, rather than artificially manipulating synchrony, future work could explore this role with more rigor, for example, such as comparing online singing groups with muted participants, or group drumming with and without synchrony. Additionally, we do not know the extent to which severity of disease, medication use and timing, length of time participating in the group impacted these results. Given that both groups had been meeting for over a year, it is likely that both had moved past the initial phase where group dynamics and feelings of social connection with the group are more unstable or in flux (e.g., see ice breaking effect,41). This implies that any early adjustments related to forming the group and establishing relationships among members have already been addressed, leading to more stable and mature interactions within the group; however, future research should assess individual differences and length of time in the group as covariates. A key limitation of this study is the lack of participant demographic and disease information. As Parkinson’s disease varies greatly between individuals, this lack of information makes it difficult to determine whether differences between groups were due to the interventions themselves or pre-existing group differences. Future studies should prioritize the collection of detailed demographic and disease-related data to account for these variations. Moreover, we did not measure participants’ rapport with their session leader. We acknowledge that this is an important factor, as a well-liked and trusted leader can significantly influence engagement and outcomes. Lastly, the small sample size warrants caution when interpreting the findings.

While singing and yoga share many similarities that promote wellbeing, including cardiovascular engagement, movement, deep breathing, and pleasure induction, they also exhibit some important differences. Notably, only group singing involves a shared rhythmic experience that facilitates interpersonal movement synchronization. This explanation is consistent with evolutionary perspectives of group music making, which suggest such activities involving movement synchrony evolved to develop and maintain strong social bonding necessary for survival7. We also acknowledge that synchronizing with a group presupposes shared goals and group-level achievements, which may also promote social cohesion. In contrast, yoga tends to afford a more individualized sense of accomplishment. While both activities yield wellbeing benefits for members including increases in mood and reductions in cortisol, the findings of this study suggest that group singing may afford a heightened capacity for fostering social closeness. These changes may ultimately manifest in feelings of trust and social bonding coupled with reductions in social isolation. Whatsmore, there is growing evidence that an ongoing program of group singing is well suited to managing vocal production challenges associated with PD2,3,42. This potential for communication and wellbeing outcomes from the same activity make group singing uniquely suited to support people living with PD.

Data availability

Data availability: De-identified data from this study will be made available by emailing the corresponding author.

References

Prenger, M., Madray, R., Van Hedger, K., Anello, M. & MacDonald, P. A. Social symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s Disease 2020, 8846544. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8846544 (2020).

Stegemöller, E. L. et al. The effects of group therapeutic singing on cortisol and motor symptoms in persons with Parkinson’s disease. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 15, 703382 (2021).

Tamplin, J., Morris, M. E., Marigliani, C., Baker, F. A. & Vogel, A. P. ParkinSong: A controlled trial of singing-based therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 33(6), 453–463 (2019).

Irons, J. Y. et al. Group singing improves quality of life for people with Parkinson’s: An international study. Aging Ment. Health 25(4), 650–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1720599 (2021).

Gick, M. L. Singing, health and well-being: A health psychologist’s review. Psychomusicol. Music Mind Brain 21(1–2), 176. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0094011 (2011).

Good, A. & Russo, F. A. Changes in mood, oxytocin, and cortisol following group and individual singing: A pilot study. Psychol. Music 50(4), 1340–1347. https://doi.org/10.1177/03057356211042668 (2022).

Dunbar, R. I. On the evolutionary function of song and dance. Music, Language, Hum. Evolut., 201–14 (2012).

Müller, V. & Lindenberger, U. Cardiac and respiratory patterns synchronize between persons during choir singing. PLoS ONE 6(9), e24893–e24893. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0024893 (2011).

Thompson, W. F. & Russo, F. A. Facing the music. Psychol. Sci.-Cambridge 18(9), 756. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01973 (2007).

Good, A. & Russo, F. A. Singing promotes cooperation in a diverse group of children. Soc. Psychol. 47, 340–344. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000282 (2016).

Good, A., Choma, B. & Russo, F. A. Movement synchrony influences intergroup relations in a minimal groups paradigm. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 39(4), 231–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2017.1337015 (2017).

Hove, M. J. & Risen, J. L. It’s all in the timing: Interpersonal synchrony increases affiliation. Soc. Cogn. 27(6), 949–960. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2009.27.6.949 (2009).

Kirschner, S. & Tomasello, M. Joint music making promotes prosocial behavior in 4-year-old children. Evol. Hum. Behav. 31(5), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.04.004 (2010).

Wiltermuth, S. S. & Heath, C. Synchrony and cooperation. Psychol. Sci. 20(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02253 (2009).

Russo, F. A. Joint speech and its relation to joint action. Music. Percept. 37(4), 359–362. https://doi.org/10.1525/mp.2020.37.4.359 (2020).

Kwok, J. Y. et al. Effects of mindfulness yoga vs stretching and resistance training exercises on anxiety and depression for people with Parkinson disease: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 76(7), 755–763. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0534 (2019).

Roland, K. P. Applications of yoga in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic literature review. Res. Rev. Parkinsonism 4, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPRLS.S40800 (2014).

Sharma, N. K., Robbins, K., Wagner, K. & Colgrove, Y. M. A randomized controlled pilot study of the therapeutic effects of yoga in people with Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Yoga 8(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-6131.146070 (2015).

Eda, N., Ito, H. & Akama, T. Beneficial effects of yoga stretching on salivary stress hormones and parasympathetic nerve activity. J. Sports Sci. Med. 19(4), 695 (2020).

Fiori, F., Aglioti, S. M. & David, N. Interactions between body and social awareness in yoga. J. Altern. Complementary Med. 23(3), 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2016.0169 (2017).

Keller, P. E., Novembre, G. & Hove, M. J. Rhythm in joint action: Psychological and neurophysiological mechanisms for real-time interpersonal coordination. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 369(1658), 20130394. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0394 (2014).

Repp, B. H. Sensorimotor synchronization: A review of the tapping literature. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 12, 969–992. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206433 (2005).

Chanda, M. L. & Levitin, D. J. The neurochemistry of music. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17(4), 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.02.007 (2013).

Tarr, B., Launay, J. & Dunbar, R. I. Music and social bonding:“self-other” merging and neurohormonal mechanisms. Front. Psychol. 5, 103498. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01096 (2014).

Fancourt, D. et al. Singing modulates mood, stress, cortisol, cytokine and neuropeptide activity in cancer patients and carers. Ecancermedicalscience 10, 631. https://doi.org/10.3332/ecancer.2016.631 (2016).

Kreutz, G., Bongard, S., Rohrmann, S., Hodapp, V. & Grebe, D. Effects of choir singing or listening on secretory immunoglobulin A, cortisol, and emotional state. J. Behav. Med. 27(6), 623–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-004-0006-9 (2004).

Riley, K. E. & Park, C. L. How does yoga reduce stress? A systematic review of mechanisms of change and guide to future inquiry. Health Psychol. Rev. 9(3), 379–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2014.981778 (2015).

Harvey, A. R. Links between the neurobiology of oxytocin and human musicality. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 14, 350. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2020.00350 (2020).

MacDonald, K. & MacDonald, T. M. The peptide that binds: A systematic review of oxytocin and its prosocial effects in humans. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 18(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3109/10673220903523615 (2010).

Crockford, C., Deschner, T., Ziegler, T. E. & Wittig, R. M. Endogenous peripheral oxytocin measures can give insight into the dynamics of social relationships: A review. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 8, 68. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00068 (2014).

Kreutz, G. Does singing facilitate social bonding?. Music Med. 6(2), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.47513/mmd.v6i2.180 (2014).

Keeler, J. R. et al. The neurochemistry and social flow of singing: Bonding and oxytocin. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 518. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00518 (2015).

Schladt, T. M. et al. Choir versus solo singing: Effects on mood, and salivary oxytocin and cortisol concentrations. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11, 430. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00430 (2017).

Bowling, D. L. et al. Endogenous oxytocin, cortisol, and testosterone in response to group singing. Hormones Behavior 139, 105105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2021.105105 (2022).

Kox, M. et al. Voluntary activation of the sympathetic nervous system and attenuation of the innate immune response in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111(20), 7379–7384. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1322174111 (2014).

Watson, D., Clark, L. A. & Carey, G. Positive and negative affectivity and their relation to anxiety and depressive disorders. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 97(3), 346. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.97.3.346 (1988).

Aron, A., Aron, E. N. & Smollan, D. Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 63(4), 596. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596 (1992).

Moerbeek, M. The consequence of ignoring a level of nesting in multilevel analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 39(1), 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_5 (2004).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. (2014) arXiv preprint arXiv:1406.5823

Hales, A. H. One-tailed tests: Let’s do this (responsibly). Psychological Methods (2023).

Pearce, E., Launay, J. & Dunbar, R. I. The ice-breaker effect: Singing mediates fast social bonding. Royal Soc. Open Sci. 2(10), 150221. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150221 (2015).

Good, A. et al. Community choir improves vocal production measures in individuals living with Parkinson’s disease. J. Voice https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2022.12.001 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the partnership of UTurn Parkinson’s in all aspects of this study from recruitment through testing. We are also grateful for funding support from the Faculty of Arts and Toronto Metropolitan University, The Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and the Grammy foundation. This study would not have been possible without the commitment of Tim Hague, Heitha Forsyth, Ifrah Zohair, and the U-Tunes singers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G. and F.R. designed and conducted the experiment. A.P. conducted the salivary analysis and S.G carried out the statistical analysis. A.G took the lead in writing the manuscript with support from F.R., A.P. and S. G.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Good, A., Pachete, A., Gilmore, S. et al. Comparing the biopsychosocial impact of group singing and yoga activities in older adults living with Parkinson’s disease. Sci Rep 15, 26713 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09200-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09200-x