Abstract

This study evaluated the properties of concrete in which natural coarse aggregates were replaced with 30%, 50%, or 100% air-cooled blast furnace slag (ACBFS) aggregates. At all aggregates replacement levels, concrete porosity remained below 9.55%, indicating good quality concrete. The high friction between ACBFS aggregates and mortar when the w/b ratio was 0.4, was mitigated when the ratio was increased to 0.45, likely due to pore structure refinement at the interfacial transition zone (ITZ). When the ACBFS content exceeded 50%, chloride ion penetrability was rated as high, potentially limiting its use in durability-sensitive applications. However, increasing the ACBFS replacement percentage consistently enhanced compressive strength, likely due to the reaction between ACBFS and portlandite, forming additional C–S–H and resulting in a denser cementitious matrix. After 56 days, concrete with 100% ACBFS achieved 25.76% higher strength than the control mix with natural aggregates. ACBFS aggregates may have facilitated internal curing through moisture desorption, refining the pore structure within the matrix and interfacial transition zone (ITZ), as confirmed by SEM images. This study presents critical findings that support the use of recycled ACBFS in concrete for structural engineering applications, as a partial or complete replacement for natural coarse aggregates, thereby contributing to the conservation of natural resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The construction industry contributes significantly to the global environmental footprint through the release of substantial amounts of CO₂ into the atmosphere and the depletion of natural resources, including fine and coarse aggregates. Concrete is the most utilized construction material because of its durability, accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and adaptability. Concrete production has reached billions of tons per year and is projected to rise further in the coming decades. The increasing demand raises concerns about the long-term sustainability of the natural resources it relies on, including natural limestone and sand, which are among the most heavily mined materials globally. The use of air-cooled blast furnace slag aggregates (ACBFS) as a partial or full substitute for natural aggregates in concrete pavements supports the United Nations’ sustainability goals by preserving natural resources. Electric Arc Furnace Slag (EAFS) aggregates, another recyclable byproduct of the metal-making industry, share many similarities with ACBFS, including an angular and rough texture, higher unit weight compared to natural aggregates, and good mechanical strength. However, limited studies have investigated the incorporation of ACBFS aggregates into concrete structures. This article evaluates the essential properties of concrete with ACBFS aggregates as a full or partial substitute for natural limestone aggregates. These properties include tensile strength, compressive strength, chloride penetration resistance, water permeability, and water absorption.

The properties of slag in general, and ACBFS aggregates in particular, vary significantly depending on several factors, including the material they are derived from and the manufacturing techniques1. Due to the relatively higher porosity of slag aggregates relative to natural aggregates, their absorption and desorption characteristics were studied to assess their suitability as internal curing elements. House et al.1 reported lower absorption and desorption of ACBFS aggregates compared to expanded slag aggregates. In addition to absorption and desorption, the depth of water penetration under pressure is also an important concrete transport property. Concrete incorporating EAFS aggregates exhibited greater depth of water penetration compared to concrete with limestone aggregates2which can adversely affect durability of concrete.

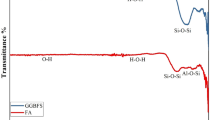

In general, ACBFS contain more than 50% crystalline phases, much more than blast furnace slag produced by water quenching3. Therefore, water-quenched slags, with their high content of amorphous phases are more reactive through high hydration than ACBFS. In general, ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) is more reactive and is used as a supplementary cementitious material (SCM) or in alkali-activated binders, while ACBFS is suitable for use as an aggregate4. In applications beyond building construction, environmental testing has indicated that ACBFS aggregates used as base/subbase under pavement to remove phosphate in passive stormwater systems are generally safe5. ACBFS aggregates were evaluated for environmental safety by testing for metals listed on the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Target Analyte List (TAL). When compared to typical soils and similar materials, ACBFS aggregates demonstrated higher environmental quality, with lower metal concentrations and leaching levels. In addition, at alkaline pH levels, leaching of regulated metals was either undetectable or within U.S. federal drinking water standards. Additionally, water that had passed through the slag showed over 90% survival in aquatic life tests, indicating low toxicity5. Similarly, Monosi et al.6 reported that the leaching of metals from EAFS aggregates remained below limits set by relevant standards. Tests by Singh et al.7 revealed that the leaching of hazardous elements from electric arc furnace slag was within permissible limits for aggregates in construction.

ACBFS is characterized by a crystalline structure that forms due to its slow solidification under ambient conditions outside the blast furnace. Oxides such as CaO, SiO₂, Al₂O₃, and MgO constitute approximately 95% of ACBFS, while the remaining 5% consists of other elements, including manganese, sulfur, titanium, iron, fluorine, sodium, and potassium. The chemical composition of ACBFS aggregates varies significantly between steel manufacturers and across countries due to differences in steel manufacturing standards and protocols. The chemical and physical properties of aggregates influence the mechanical and durability characteristics of concrete. The incorporation of ACBFS aggregates into concrete leads to the release of sulfates into the pore solution8. These sulfates contribute to the formation of ettringite within the microstructure, which helps fill voids and enhance concrete strength and durability by mitigating freeze-thaw damage8. However, excessive sulfate content and excessive ettringite formation can potentially weaken the concrete microstructure9.

Several key factors related to ACBFS aggregates, including their angular shape, rough texture, and porous structure, significantly influence the flexural and splitting tensile strengths of concrete10. Ríos et al.11 observed an improvement in the bond strength between aggregates and cement paste when ACBFS was incorporated as a partial substitute for natural aggregates, up to an optimal replacement level. Wang et al.12 reported significant improvements in both compressive and splitting tensile strengths when using ACBFS in gradations of 5–20 mm, especially at early ages. Some studies have proposed methods to reduce the rate of water absorption and porosity of concrete made with ACBFS aggregates, bringing them closer to those of concrete made with natural aggregates13. Concrete incorporating these modified ACBFS aggregates exhibited superior flexural and splitting tensile strengths in comparison to those made with limestone and sandstone aggregates. However, the extent of improvement in tensile strength compared to concrete with natural aggregates depends on the content of ACBFS aggregates14. Self-compacting concrete (SCC) incorporating ACBFS aggregates necessitates additional vibration and water because of the increased water absorption of these aggregates. Rios et al.11 observed a substantial reduction in the splitting tensile strength of SCC incorporating 100% ACBFS and a high water-to-binder (w/b) ratio. However, Cao et al.15 found insignificant changes in the splitting tensile strength of concrete made with various replacement percentages of ACBFS aggregates (0–100%) in relation to concrete made with crushed limestone. Similar to ACBFS, the angular and rough texture of EAFS aggregates enhances the quality of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between the aggregates and the surrounding matrix, making it superior to that of natural aggregates, and leading to enhanced mechanical strength16. In concrete containing approximately 53% EAFS aggregates, an improvement in concrete tensile strength was attributed to shape and texture of EAFS aggregates, which contributed to better bond strength with the cement paste17. The improvement in the ITZ associated with the rough texture of EAFS aggregates also resulted in improved bond strength between the concrete and the reinforcing bars, compared to concrete incorporating natural or crushed aggregates18. Despite limited research, ACBFS aggregates are likely to exhibit similar properties to EAFS aggregates in terms of the effects of surface roughness and angularity.

Incorporating steel fibers significantly enhanced tensile and flexural capacities of concrete. This is due to the ability of the fibers to bridge the cementitious matrix at a micro-level, resulting in a quasi-ductile concrete composite. Beyond enhancing these strengths of concrete, fibers also significantly reduce its water absorption capacity19.

The relatively higher surface roughness and larger angle of friction of ACBFS aggregates, compared to natural aggregates, increase friction between aggregate particles and mortar, affecting the workability and flow of concrete. The concrete becomes less workable as the proportion of ACBFS aggregates increases15,20. Similar to ACBFS, the shape and texture of EAFS aggregates cause a reduction in workability of concrete21. Therefore, a 15% limit was suggested for replacing natural aggregates with EAFS to control the amount of superplasticizer required and to reduce drying shrinkage22. The increase in drying shrinkage was attributed to the increased water absorption caused by the greater porosity of aggregates. Therefore, drying shrinkage can be mitigated by soaking the recycled aggregates prior to mixing them with concrete constituents.

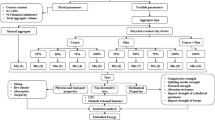

The sorptivity and mechanical properties of concrete with alkali-activated slag have been studied extensively in recent years, including assessments of its global warming potential23. However, the mechanical behavior of concrete incorporating ACBFS aggregates remains under-researched, with significant gaps in knowledge. Experimental data is needed to develop a proper understanding and to improve computational prediction models24. This study aimed to evaluate the effect of various replacement percentages of natural aggregates with ACBFS aggregates on fresh properties such as workability of concrete, as well as mechanical properties including flexural strength, splitting tensile strength, and compressive strength. The study also examined the effect of ACBFS aggregates content on selected transport properties, including porosity and permeability of concrete, in comparison to a control mix prepared using 100% natural aggregates. Findings add critical information to the limited body of knowledge on the use of recycled ACBFS aggregates as partial or complete replacement of natural aggregates.

Materials and methods

This section outlines the characteristics of the materials utilized in the study, the mix design, and the testing methodology.

Material properties

Cementitious materials

ASTM Type I Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC)25 was the only binder used in the experimental program reported in this article. The chemical composition of the OPC used in the study was determined using the X-ray fluorescence (XRF) method in accordance with ASTM C11426, and the results are shown in Table 1. Some of the physical characteristics of the OPC used in the study, including specific surface, soundness, setting time, and compressive strength are shown in Table 2.

Characteristics of coarse and fine aggregates

The natural dune sand used in this study was sourced from Al Ain City, UAE, while natural coarse aggregates were obtained from the Ras Al-Khaimah Emirate, UAE. ACBFS aggregates were supplied by a local provider. ACBFS aggregates were used to partially or fully substitute natural aggregates in four main concrete mixes. Figure 1 illustrates the gradation of ACBFS aggregates, natural limestone aggregates, and fine aggregates used in this study. The density, water absorption, acid-soluble chloride content, and sulfate content of coarse and fine aggregates were determined and are presented in Table 3. It is worth noting that the water absorption of ACBFS aggregates, determined according to ASTM C12728, was higher than that of natural aggregates. This is likely to influence the water absorption of concrete produced using these two types of aggregates.

Sulfide sulfur, in the form of sulfide ions (S2−), is generally present in the crystal structure of various metals forming ACBFS aggregates. Iron sulfide (FeS₂) is an example of a mineral in ACBFS aggregates that contains sulfides. In the presence of water, sulfides may gradually oxidize to produce sulfate ions (SO2−4). Table 3 shows that the acid-soluble sulfate content in ACBFS is higher than that in natural aggregates. The angle of friction of ACBFS aggregates is also generally greater compared to natural crushed aggregates29which affects concrete workability.

Sieve analysis of dune sand, natural coarse aggregates, and ACBFS aggregates was conducted according to ASTM C136-96a30 and the gradation is shown in Fig. 2.

Table 4 shows the chemical composition of ACBFS aggregates. Silicon dioxide (SiO2) and calcium oxide (CaO) were the major components of ACBFS used in this study. ACBFS aggregates also contain small amounts of aluminum, magnesium, and iron oxides. Figure 3 presents scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the recycled ACBFS at various magnifications. The morphology of ACBFS aggregates reveals rough surfaces, especially in magnified images, where the irregularity of particles is particularly notable. The results of energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) are shown in Fig. 3d, highlighting prominent peaks of calcium, silicon, aluminum, and magnesium.

Concrete workability and w/b ratio

A polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer, marketed under the commercial name Fosroc Structuro W420, was used in this study to control slump along with the w/b ratio. The effect of ACBFS aggregate content on concrete workability was observed by testing four mixes: Mix 1 and Mix 1.1 were prepared with natural coarse aggregates; Mix 2 and Mix 2.1 with 30% ACBFS aggregates (70% natural aggregates); Mix 3.0 and Mix 3.1 with 50% ACBFS aggregates; and Mix 4 with 100% ACBFS aggregates. Table 5 shows the w/b ratio and the resulting slump of each mix.

Increasing the ACBFS coarse aggregate content tended to decrease workability for the same w/b ratio. This led to adjustments in both the w/b ratio and superplasticizer dosage to control workability and reduce friction within the mix and against the mixer blades. The decrease in workability due to high friction is attributed to the rougher surface texture and more angular geometry of ACBFS aggregates compared to natural aggregates.

For Mix 2, workability decreased significantly to Mix 1 at w/b = 0.4. As a result, the w/b ratio was increased in Mix 3 (w/b = 0.43) and Mix 4 (w/b = 0.45) to enhance workability, as shown in Table 5. A w/b ratio of 0.45 was found to provide a high workability of 210 to 220 mm for Mix 4, which was prepared with 100% ACBFS aggregates and consequently experienced the highest friction.

Concrete mix constituents

To understand the influence of progressively substituting natural coarse aggregates with ACBFS aggregates, four mix groups were developed: Mix 1 & 1.1, Mix 2 & 2.1, Mix 3 & 3.1, and Mix 4. Mix 1 and Mix 1.1 serve as the reference mix, containing 100% natural aggregates but with two different w/b ratios, as discussed earlier in this article. Similarly, Mix 2 & Mix 2.1 both contain 30% ACBFS aggregates and 70% natural aggregates but have different w/b ratios, as shown in Table 6. The proportioning of mixes, shown in Table 6, was carried out in accordance with BS 8500 − 231 for class 32/5 N, in which the w/b ratio was kept below 0.55. Mixes 1.1, 2.1, and 3.1 were produced using a w/b ratio of 0.45, as it was found to be the most suitable for Mix 4, which uses 100% ACBFS aggregates. All mixes used ASTM Type I OPC25.

Mixing and casting procedures

Mixing and curing followed the guidelines of ASTM C192/C192M32. The material quantities described in the previous section were weighed and recorded. Prior to each mixing cycle, the mixer was cleaned to remove any residue from previous cycles. After mixing, concrete workability was measured and recorded in accordance with the relevant ASTM standard. Samples were demolded 24 h after casting and then transferred to temperature-controlled curing tanks, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

Measurement of concrete slump

The slump of the concrete mixes was measured in accordance with ASTM C14333, and the results are shown in Fig. 5. The highest slump of 260 mm was exhibited by Mix 1, which was prepared using 100% natural aggregates and a w/b ratio of 0.4. When 30% of the natural aggregates were replaced by ACBFS aggregates at the same w/b ratio to produce Mix 2, mixing became difficult due to significant friction between the aggregates, mortar, and mixer. As a result, the slump of the mix dropped significantly to 150 mm. This is consistent with published literature on concrete incorporating aggregates with rough textures and angular geometry22.

When ACBFS aggregates replaced 50% of the total aggregates in Mix 3, it became necessary to increase the w/b ratio to 0.43, as presented in Table 5. This adjustment improved mixability, and the slump of Mix 3 increased to 185 mm. Mixing concrete with 100% ACBFS (Mix 4) involved even higher friction and slump loss; therefore, the w/b ratio was increased to 0.45, as shown in Table 5. Consequently, the slump of Mix 4 increased to a reasonable 210 mm.

The slump test results indicate that increasing the ACBFS aggregate content from 0% (Mix 1) to 30% (Mix 2) at a constant w/b ratio of 0.4 substantially decreases concrete slump, which is consistent with published literature21. However, the slump increases with the increase in w/b ratio (Mixes 3 and 4), even as the ACBFS aggregate content increases to 50% in Mix 3 and 100% in Mix 4. A w/b ratio of 0.45 produced a reasonable concrete slump even with 100% ACBFS aggregates. Therefore, in mixes 1.1, 2.1, and 3.1, a w/b ratio of 0.45 was used.

Table 7 shows the densities (kg/m2) of hardened concrete prepared using each of the four mixes. It is evident that ACBFS aggregates increase concrete unit weight significantly, from 23.22 kN/m³ for Mix 1 (100% natural aggregates) to 27.66 kN/m³ in Mix 4 (100% ACBFS aggregates). The high unit weight may limit the application of mixes with a high ACBFS aggregate content to structures or structural members where the increase in self-weight is offset by the benefits of recycling this industrial byproduct. Concrete made with recycled aggregates from the steel-making industry, such as EAFS, has consistently been reported to have higher density than that made with natural aggregates34.

Test methods

This section describes the testing procedures used to determine the following concrete properties related to durability: (1) water absorption, (2) porosity, (3) water permeability, (4) chloride penetration, and (5) sulfate and chloride contents. In addition, compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, and flexural strength were determined.

Water absorption of concrete

The result of this test provides an indication of concrete durability and resistance to damage from frost, chemicals, abrasion, and other factors. The water absorption test determines the amount of water concrete can absorb into its pores, serving as a measure of concrete porosity.

The test was performed in compliance with BS 1881 Part 12235 on concrete samples that were oven-dried for 72 h. The samples were subsequently submerged in water for 24 h at 20 °C ± 2 °C, ensuring no air pockets remained trapped around them. After immersion, each sample was taken out of the water, surface-dried to eliminate excess moisture, and then weighed. The water absorption was calculated as the percentage increase in the specimen’s mass, as indicated by Eq. (1).

where:

\(\:{m}_{damp}\)mass of dry specimen (kg).

\(\:{m}_{dry}\) : mass of sample after immersion in water (kg)

The calculated absorption is corrected to account for variation in sample length. The correction factor is given by Eq. (2).

Porosity of hardened concrete (absorption in vacuum test)

The porosity of concrete represents the proportion of interconnected voids in relation to its total volume. Another method for measuring concrete porosity is the vacuum absorption test proposed by RILEM CPC 11.336. In this experiment, a concrete sample is cured for 28 days, removed from the curing tank, and dried in a ventilated oven at 105 °C ± 5 °C, then cooled to 20 °C ± 3 °C. The mass, m1, of the dried and cooled sample is determined. The specimen is then immersed in water for 24 h under controlled vacuum conditions to ensure effective water penetration into the concrete pores and the removal of any entrapped air. While the sample is submerged, its apparent mass, \(\:{\text{m}}_{3}\), is measured. After 24 h of immersion, the sample is taken out, and its saturated surface-dry mass, \(\:{\text{m}}_{2}\), is recorded. All masses are measured to the nearest 0.1%. Porosity is calculated using Eq. 3.

Water permeability of concrete under pressure

Water permeability is a concrete transport property determined by measuring the extent of water ingress under applied pressure through a concrete specimen. In this study, the water permeability test was performed in compliance with BS 12,390 Part 837 on 150 mm cubic samples. Each specimen was subjected to a constant water pressure of 500 kPa (equivalent to a 50 m water head) for 72 h. After the test, the specimen was split open, and the depth of water penetration (in millimeters) was measured. Concrete with low permeability has better resistance to the corrosion of reinforcing steel bars and generally exhibits greater durability.

Rapid chloride penetration test

The rapid chloride penetration (RCP) test of concrete specimens was conducted according to ASTM C120238. During the test, 100 mm diameter × 50 mm high concrete specimens were placed in test cells with two chambers, as shown in Fig. 6. One chamber contained a 3% NaCl solution, whereas the other held a 0.3 N NaOH solution. A potential of 60 volts was applied across the specimen for 6 h, driving chloride ions from the NaCl solution through the concrete specimen into the NaOH solution. The electric charge transmitted through the specimen was recorded every 30 min. The total charge passed during the test was used to calculate the charge passed per unit area. ASTM C120238 classifies concrete chloride permeability as high when the passing charge exceeds 4000 Coulombs. Similarly, chloride permeability is classified as low, very low, or negligible when the passing charge is below 2000 Coulombs.

Content of sulphate and chloride in hardened concrete with and without ACBFS coarse aggregates

The sulfate content in concrete made with Mixes 1 to 4 was determined according to BS 188135, which measures the concentration of sulfate ions (SO2−4) in hardened concrete. The test is conducted on a representative concrete sample, which is crushed and dissolved in acid. The sulfate content is then determined using either a gravimetric or volumetric method. Sulfate can interact with the products of cement hydration, resulting in the development of expansive compounds. When the sulfate content is high, these expansive products generate internal pressure, causing cracking and subsequent deterioration of concrete. Concrete with a sulfate content below 0.2% has good resistance to sulfate-induced damage, while content greater than 0.8% indicates the formation of higher amounts of expansive material and an increased potential for cracking and deterioration. It is important to note that concrete resistance to sulfate attack is also influenced by other factors, such as the type of cement used, the w/b ratio, and the curing conditions39. The concentration of chloride ions (Cl⁻) in hardened concrete, represented by Mixes 1 to 4, was also determined in accordance with BS 188135. The test is conducted on a representative concrete sample, which is crushed and dissolved in acid. The chloride content is then determined using either a gravimetric or volumetric method.

Compressive strength

To determine the compressive strength of concrete prepared using each of the four mixes (Mix 1 to Mix 4), 150 × 150 × 150 mm cubes were cast and cured according to BS EN 12390-2 37. On the test day, the cubes were weighed, and their dimensions were validated after formwork removal. The load was then applied to the test specimens without shock at a nominal rate of 0.6 ± 0.2 N/mm2.s. The load was continuously increased until failure, and the maximum load applied to the specimen was recorded.

Flexural strength

To evaluate the flexural performance of concrete prepared using each of the four mixes (Mix 1 to Mix 4), 750 mm long beams were cast and cured in accordance with BS 12390-240. The cross-sectional dimensions were 150 mm × 150 mm. On the test day, the beams were weighed, and their dimensions were validated after removal from the formwork, as shown in Fig. 7a.

The beams were placed in the testing device, supported by two rollers with a spacing of 3d (where d is the depth of the specimen), as shown in Fig. 7b and c. The load was gradually and uniformly applied at a nominal rate of 0.04 to 0.06 N/mm2/s until the beam failed. The load was applied through two upper rollers, spaced d apart, connected by a cross arm that transmitted the total load from the machine.

Splitting tensile strength

The splitting tensile strength was determined by testing 150 mm (diameter) × 300 mm cylindrical specimens in accordance with BS 1881: Part 117: 1983 41. Sample preparation and curing were conducted according to BS EN 12390-2 40. On the test day, the samples were wiped clean, weighed, and their dimensions were measured. The samples were then placed in the centering jigs, as shown in Fig. 8. The specimens were subjected to loading at a rate of 0.02 to 0.04 N/mm2 until failure, and the tensile splitting strength, \(\:{{\upsigma\:}}_{\text{c}\text{t}}\), was calculated.

Microstructural analysis

Microstructural analysis of ACBFS and hardened concrete samples was performed using Phenom XL Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX). Hardened concrete samples, approximately 100 × 100 mm in size, were extracted from the fractured surfaces of specimens tested for compressive strength.

Results and discussion

The subsequent subsections present the outcomes of the various tests discussed in the earlier sections. The results are presented, and the main observations and findings are discussed.

Water absorption of concrete

The water absorption of concrete is a measure of its porosity. The variation in water absorption with aggregate replacement percentage, as represented by Mix 1 to Mix 4, is shown in Fig. 9. Increasing the replacement percentage of natural coarse aggregates with ACBFS aggregates leads to higher water absorption in concrete. This is largely due to the higher water absorption capacity of ACBFS aggregates themselves. Nonetheless, the highest increase in water absorption, which occurred in the concrete mix made with 100% ACBFS, was 10.6% compared to the control mix made with natural aggregates. Concrete made with Mix 3, which contains 50% ACBFS, exhibited only 4.375% higher water absorption than the control mix, making it more suitable for structural engineering applications where transport properties are a concern than the mix with 100% ACBFS.

Porosity of hardened concrete

At a w/b ratio of 0.4, replacing 30% of natural coarse aggregates with ACBFS aggregates (Mix 2) increased the porosity of concrete, as shown in Fig. 10. This aligns with the observed higher water absorption of ACBFS aggregates and is also linked to the mixing challenges caused by the increased friction characteristic of concrete incorporating ACBFS aggregates. However, increasing the w/b ratio from 0.4 to 0.43 while simultaneously raising the replacement percentage to 50% (Mix 2 to Mix 3) led to a reduction in porosity, possibly due to enhanced workability and overall quality associated with the higher w/b ratio. Similarly, Fig. 10 shows that increasing the replacement percentage to 100% (from Mix 3 to Mix 4) resulted in a further decrease in porosity, despite a slight increase in the water-to-binder (w/b) ratio from 0.43 to 0.45. The effect of an increased ACBFS aggregate content on concrete porosity aligns with the findings of Wang et al.42. The higher w/b ratio improved workability by mitigating friction between ACBFS aggregates and the surrounding mortar, resulting in higher-quality concrete with a finer pore structure.

Additionally, retained mixing water within the porous ACBFS aggregates may have provided an internal curing effect, leading to a reduction in capillary pores within the matrix and in the interfacial transition zone (ITZ) between the matrix and ACBFS aggregates. Notably, the porosity of all mixes remained below 10%, indicating high concrete quality regardless of ACBFS aggregate content.

Water permeability of concrete under pressure

The water permeability of concrete is affected by various aspects such as mixture composition, curing environment, and the concrete’s age43. As shown in Fig. 11, water permeability increases with higher ACBFS aggregate content. For the same w/b ratio of 0.4, replacing 30% of natural aggregates with ACBFS aggregates (Mix 2) increased water permeability from 4.5 mm to 4.67 mm, an insignificant increase of 3.8% over the control mix containing only natural aggregates (Mix 1). The water permeability of Mix 3 (5.33 mm) exceeded that of the control mix by 18.44%. This is attributed to the higher w/b ratio and greater ACBFS aggregate content in Mix 3 relative to the control mix. The mix with 100% ACBFS also exhibited an 18.44% increase in water permeability compared to the control mix. However, the higher w/b ratio of 0.45 helped reduce friction during mixing, maintaining permeability similar to that of Mix 3. It can be concluded that for the same w/b ratio, water permeability increases as the ACBFS replacement percentage increases, as evident when comparing Mix 2 to the control Mix 1.

Rapid chloride penetration (RCP) test

The RCP test is used to assess concrete’s ability to withstand chloride ion ingress. Table 8 presents the measured charge (in Coulombs) through samples taken from each of the four mixes. Figure 12 shows that the passing charge, and therefore chloride ion penetration, increases with a higher percentage of ACBFS aggregates compared to natural aggregates. The passing charge through Mix 1 classifies its chloride permeability as low, according to ASTM C120238, while Mix 2 results in borderline low to medium chloride permeability. However, Mix 3 (50% ACBFS aggregates + 50% natural aggregates) and Mix 4 (100% ACBFS aggregates) both produce concrete with high chloride permeability. This suggests that the ACBFS content should be limited to less than 50% of the total aggregate content in concrete structural elements that are likely to be exposed to chloride ions, unless appropriate precautions are taken. Chloride ion penetration is likely to increase with higher ACBFS content due to its greater water permeability compared to natural aggregates, which results in a higher charge passed. However, further research and alternative test methods may be needed to validate the findings, as the results could be influenced by metal oxides in ACBFS which enhance electrical conductivity of concrete. The RCP test measures the total ionic flow, which can be increased by the presence of metals in ACSB, rather than reflecting the actual chloride diffusion.

Sulphate and chloride contents in hardened concrete

Sulfate and chloride contents in hardened concrete produced by Mixes 1 to 4 were determined using the method described earlier in this article, and the results are shown in Table 9. All four mixes are classified as borderline medium to poor in terms of their susceptibility to the formation of expansive products due to sulfate interactions with cement hydration products44. Therefore, the aggregate type did not play a substantial role in the formation of deleterious sulfates, irrespective of the percentage of ACBFS present in the mix.

The chloride content in hardened concrete, shown in Table 9, is sufficiently low to classify all four mixes as good, according to BS 1881. Therefore, the chloride content generated within the concrete mix itself was not influenced by the aggregate type and remained low in all mixes.

Compressive strength

Figure 13 shows the variation in compressive strength after 7, 28, and 56 days of curing as the percentage of ACBFS aggregates increases from 0% (control mix) to 100% (Mix 4). For each mix, compressive strength increased with curing age, regardless of ACBFS aggregate content. After 7 days of curing, Mix 4 developed 39.29% higher compressive strength than the control Mix 1. After 28 days, Mix 4 exhibited a 22.29% increase in strength compared to the control mix made with natural aggregates. After 56 days, Mix 4 exhibited a 25.75% higher compressive strength relative to the control mix. Thus, at all curing ages, concrete mixes containing 100% ACBFS aggregates exhibited greater strength than the control mix made with natural aggregates. This suggests that ACBFS aggregates may contribute to an internal curing effect by retaining water during mixing and gradually releasing it throughout the curing process. The release of absorbed water supports the formation of hydration products, particularly at the aggregate-paste interface. The contribution of absorbed water to strength development appears to be most significant in concrete with 100% ACBFS aggregates, as evidenced by its higher 56-day strength compared to mixes with 30% and 50% replacement levels. A similar effect of replacing natural aggregates with recycled aggregates from the steel-making industry, such as EAFS, on the compressive strength of concrete has been reported in the literature17.

Compressive strength of concrete using different w/b ratios

Figure 14 shows the impact of varying the w/b ratio, along with increasing percentages of ACBFS aggregates, on compressive strength development after 7 and 28 days of curing. At the same w/b ratio of 0.4, compressive strength decreases slightly when natural limestone aggregates are substituted with 30% ACBFS aggregates (Mix 2 compared to Mix 1). This limited decrease in strength at both curing ages (7 and 28 days) is attributed to the relatively lower concrete quality associated with the low w/b ratio. The low w/b ratio contributed to high friction between ACBFS aggregates, mortar, and even the mixer, resulting in decreased concrete workability.

As the w/b ratio increased from 0.4 to 0.43 and the replacement of natural aggregates with ACBFS was raised to 50% (transitioning from Mix 2 to Mix 3), compressive strength decreased further due to the combined effect of a higher w/b ratio and increased ACBFS content. Nonetheless, the decrease was limited (from 64.45 MPa to 61.73 MPa after 28 days) as the additional water content helped overcome some of the flow resistance associated with the high ACBFS content in Mix 3 and therefore, decreased workability.

The positive and lubricating effect of increased water content is evident when the w/b ratio was raised from 0.43 to 0.45 in Mix 4, which was prepared using 100% ACBFS aggregates. The resistance to concrete flow caused by the high ACBFS content was mitigated by the higher w/b ratio, resulting in the 28-day compressive strength of Mix 4 being statistically similar to that of Mix 3. It may therefore be concluded that a low w/b ratio negatively impacts the quality and strength of concrete with a high ACBFS content due to increased friction and lower workability caused by the angular geometry of the aggregates. However, an optimal w/b ratio enhances concrete quality and compressive strength while enabling the recycling of ACBFS aggregates through partial replacement of natural aggregates.

Figure 15 compares the effects of variable and fixed w/b ratios, along with the percentage of ACBFS aggregates, on compressive strength. When the w/b ratio is maintained at 0.45, raising the ACBFS aggregate content from 0% (Mix 1) to 100% (Mix 4) leads to a consistent enhancement in compressive strength. On the other hand, when the w/b ratio is increased from 0.4 (Mix 1 and Mix 2) to 0.45 (Mix 4), along with a higher ACBFS aggregate content, compressive strength decreases slightly.

Flexural strength

Figure 16 shows the variation in flexural strength with w/b ratio and aggregate replacement percentage. When coarse aggregate was partially replaced with 30% ACBFS at w/b = 0.4, the 28-day flexural strength increased by 31.23%. As the w/b ratio increased from 0.4 to 0.43, the 28-day flexural strength increased further (from 8.53 MPa to 9.37 MPa) due to the increase in coarse aggregate replacement from 30 to 50%. This is attributed to rough texture and enhancement in the quality of bond and the ITZ between the cement paste and aggregates. This enhancement in strength, resulting from improvements in the ITZ in concrete incorporating recycled aggregates from the steel-making industry, including EAFS, has been consistently reported in the literature17. However, increasing the w/b ratio from 0.43 to 0.45 resulted in a decrease in 28-day flexural strength (from 9.37 MPa to 7.19 MPa) even as natural coarse aggregates were fully replaced by ACBFS (Mix 4). This pattern indicates that a w/b ratio exceeding 0.43 reduces flexural strength at 7 and 28 days compared to lower ratios, when natural coarse aggregates are entirely or partially substituted with ACBFS. Nonetheless, the flexural strength measured at 28 days for concrete containing 100% ACBFS (7.19 MPa) exceeds that of concrete incorporating only natural aggregates (6.5 MPa), despite the ACBFS mix having a higher w/b ratio (0.45).

To preclude the effect of w/b ratio variation on flexural strength, mixes 1 to 4 were prepared with a constant w/b = 0.45. The 28-day flexural strength for Mixes 1, 2, 3, and 4 is shown in Fig. 17. Although the variation in flexural strength with aggregate replacement percentage is relatively small, a 50% replacement resulted in the highest 28-day flexural strength.

Splitting tensile strength

Figure 18 shows an insignificant 2.9% increase in splitting tensile strength when the percentage of ACBFS aggregates was increased to 30% in Mix 2, following a pattern similar to that observed in flexural strength for the w/b ratio of 0.4. A further increase in ACBFS to 50% of the total aggregate content (Mix 3) resulted in a small 3.6% increase, even when the w/b ratio was raised from 0.4 (Mix 2) to 0.43 (Mix 3). Similar to flexural strength trends, when ACBFS aggregates reached 100% (Mix 4), the splitting tensile strength decreased slightly (0.74%), largely due to the increase in the w/b ratio to 0.45, as shown in Fig. 18. The relationship between splitting tensile strength and flexural strength has been examined in the literature10.

Microstructural analysis

Figure 19 presents SEM images of samples containing ACBFS aggregates after 28 days of curing. The samples analyzed were taken from the fractured concrete surface and areas containing ACBFS aggregates. Microcracks were visible in all SEM images, likely due to the fact that the samples were extracted from the fractured surfaces of tested specimens.

Figure 19a illustrates the morphology of the control mix at both low and high magnifications. A noticeable change in morphology is observed in mixes containing ACBFS aggregates compared to the control mix with only natural aggregates, suggesting that ACBFS aggregates chemically interact with the cement matrix. Figure 19b reveals a rougher surface with more pronounced voids and distinct rounded particles in the ACBFS-modified mix.

Although strength tends to increase when replacing natural aggregates with 30% ACBFS, the microstructure shows more pronounced voids and irregularities, as well as the presence of rounded particles. Concrete with 30% ACBFS aggregates (Mix 2) exhibits a different morphology, likely due to the partial chemical interaction between ACBFS and the cement matrix. This interaction may contribute to the formation of calcium silicate hydrates (C-S-H) while also increasing porosity due to the differing properties of ACBFS compared to natural aggregates. The irregular and rougher surface suggests a variation in how ACBFS aggregates bond with the cementitious matrix, potentially affecting the overall mechanical properties.

A clearer demonstration of the role of ACBFS aggregates is evident when 50% of the natural aggregates are replaced, as shown in Fig. 19c, where a partially chemically reacted ACBFS aggregate is observed. This reaction supports the hypothesis that ACBFS aggregates chemically integrate into the cementitious system, facilitating the generation of extra C-S-H and, in turn, improving compressive strength.

Finally, Fig. 19d depicts the morphology of a mix incorporating 100% ACBFS aggregates. The image highlights the agglomeration of C-S-H crystals at the interface between the cement matrix and the chemically reacted ACBFS aggregate. This phenomenon is particularly evident in the mix with 100% ACBFS aggregates, where the potential for chemical interaction between the cement matrix and the ACBFS aggregates is significantly increased.

Figure 20a shows that the control sample is predominantly composed of calcium, suggesting the formation of calcium silicate hydrates (C-S-H) and CaCO2. This baseline composition is crucial for understanding the changes observed in subsequent samples.

With the introduction of 30% ACBFS, as seen in Fig. 20b, there is a noticeable increase in oxygen and silica. This shift confirms the incorporation of ACBFS and suggests that the additional silica may contribute to further pozzolanic reactions, enhancing the cement matrix. Figure 20c demonstrates that increasing the ACBFS content to 50% further elevates oxygen levels, indicating a progressive chemical interaction that enhances matrix densification.

Lastly, Fig. 20d, which represents a 100% replacement of natural aggregates with ACBFS aggregates, reveals a substantial increase in calcium, silica, and oxygen levels. This combination fosters the formation of additional C-S-H phases, which are crucial for improving strength and reducing porosity in the concrete composite.

These observations support the conclusion that ACBFS aggregates not only chemically interact with the cement matrix but also substantially improve the strength characteristics and durability of the resulting concrete composites.

Summary and conclusions

The replacement of natural coarse aggregates with air-cooled blast furnace slag (ACBFS) aggregates helps minimize the environmental impact of construction activities and supports global sustainability goals by recycling slag and preserving natural aggregate resources. This article evaluated the critical properties of concrete in which natural aggregates were replaced with 30%, 50%, or 100% ACBFS. The key findings of the experimental program are as follows:

-

Concrete slump decreased as the replacement level of natural coarse aggregates with ACBFS increased from 30%, 50%, and 100%. This reduction is attributed to the higher roughness of ACBFS aggregates and increased friction between the concrete mix constituents. Increasing the w/b ratio from 0.4 to 0.45 has a lubricating effect on the mix as demonstrated by improved workability, even when ACBFS aggregate content was 100%.

-

Concrete with 100% ACBFS aggregates weighed 27.66 kN/m2, significantly more than concrete with natural aggregates, which weighed 23.22 kN/m2. The high unit weight of concrete with 100% ACBFS aggregates may limit its structural engineering applications or favor lower aggregate replacement percentages.

-

At a lower w/b ratio of 0.4, partial replacement of natural aggregates with 30% ACBFS increases concrete porosity and permeability. This may be attributed to higher friction within the mix, leading to poorer concrete quality. However, increasing the w/b to 0.43 and 0.45 respectively mitigated internal friction, decreased porosity, and improved concrete quality, even as the content of ACBFS was increased to 50% and 100%.

-

The chloride ion penetrability of concrete with 50% or more ACBFS aggregates was rated as high. Therefore, such concrete may be limited to applications with a low risk of chloride exposure or where sufficient precautions have been taken to protect reinforcing steel bars. When natural aggregates were replaced with 30% ACBFS aggregates, the chloride penetration resistance was rated as low to moderate.

-

At a w/b ratio of 0.45, the compressive strength of concrete increases as the replacement percentage of ACBFS aggregates rises from 0 to 100%. After 56 days of curing, concrete with 100% ACBFS aggregates exhibited 25.75% higher strength than the control mix made with natural aggregates. SEM images highlighted changes in microstructure and the agglomeration of C–S–H crystals at the interface between the cement matrix and the chemically reacted ACBFS aggregate. The formation of additional C–S–H resulted in densification and promoted the observed strength development.

-

The modulus of rupture increases as the replacement percentage of natural aggregates with ACBFS increases. The effect of increasing ACBFS content on flexural strength remains consistent when the w/b ratio was increased from 0.4 to 0.43. This is due to the better interlock and improved bond between the aggregates and the surrounding paste, provided by the rough surface of ACBFS. However, increasing the w/b ratio to 0.45 decreases flexural strength, even with 100% ACBFS aggregates.

Future research should evaluate the structural behavior of reinforced concrete elements, including but not limited to bond strength, flexural response, and axial compression. Furthermore, research is needed to explore the fresh and hardened properties of concrete incorporating ACBFS aggregates, as well as sustainable alternative binders to cement, such as alkali-activated industrial byproducts.

Data availability

All data used in this manuscript are included in the provided figures and tables.

References

House, M. et al. Influence of slag aggregate production on its potential for use in internal curing. Transp. Res. Record: J. Transp. Res. Board. 2441, 105–111 (2014).

González-Ortega, M. A., Cavalaro, S. H. P., de Sensale, R., Aguado, A. & G. & Durability of concrete with electric Arc furnace slag aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 217, 543–556 (2019).

Tripathy, S. K. et al. Utilisation perspective on water quenched and air-cooled blast furnace slags. J. Clean. Prod. 262, 121354 (2020).

de Matos, P. R. et al. Use of air-cooled blast furnace slag as supplementary cementitious material for self-compacting concrete production. Constr. Build. Mater. 262, 120102 (2020).

Grubb, D. G. & Berggren, D. R. V. Air-Cooled blast furnace slag. I: characterization and leaching context. J Hazard. Toxic. Radioact Waste 22, (2018).

Monosi, S., Ruello, M. L. & Sani, D. Electric arc furnace slag as natural aggregate replacement in concrete production. Cem. Concr Compos. 66, 66–72 (2016).

Singh, S. K., Vashistha, P., Chandra, R. & Rai, A. K. Study on leaching of electric arc furnace (EAF) slag for its sustainable applications as construction material. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 148, 1315–1326 (2021).

Panchmatia, P., Kim, T. & Olek, J. Effects of Air-Cooled blast furnace slag aggregate on pore solution chemistry of cementitious systems. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 32, (2020).

Mohamed, O. A., Rens, K. L. & Stalnaker, J. J. Factors affecting resistance of concrete to freezing and thawing damage. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 12, 26–32 (2000).

Mohamed, O. A., Syed, Z. I. & Najm, O. F. Splitting tensile strength of sustainable self-consolidating concrete. Procedia Eng. 145, 1218–1225 (2016).

Ríos, J. D., Vahí, A., Leiva, C., Martínez-De la Concha, A. & Cifuentes, H. Analysis of the utilization of air-cooled blast furnace slag as industrial waste aggregates in self-compacting concrete. Sustainability 11, 1702 (2019).

Wang, A., Deng, M., Sun, D., Li, B. & Tang, M. Effect of crushed air-cooled blast furnace slag on mechanical properties of concrete. J. Wuhan Univ. Technology-Mater Sci. Ed. 27, 758–762 (2012).

Irfan, I., Tobo, H., Ta, Y. & Date, S. Study on the utilization of innovative Air-cooled slag aggregates in precast concrete. Int. J. Struct. Civil Eng. Res. 252–257. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijscer.6.4.252-257 (2017).

Mohamed, O. A., Ghanam, O. N., Hamdan, A. R. A. & Zuaiter, H. A. Flexural and splitting tensile strengths of sustainable concrete with natural and recycled Air-Cooled blast furnace slag aggregates. 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-76025-9_23 (2025).

Cao, Q., Nawaz, U., Jiang, X., Zhang, L. & Ansari, W. S. Effect of air-cooled blast furnace slag aggregate on mechanical properties of ultra-high-performance concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 16, e01027 (2022).

Arribas, I., Santamaría, A., Ruiz, E., Ortega-López, V. & Manso, J. M. Electric arc furnace slag and its use in hydraulic concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 90, 68–79 (2015).

Faleschini, F. et al. High performance concrete with electric Arc furnace slag as aggregate: Mechanical and durability properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 101, 113–121 (2015).

Faleschini, F., Santamaria, A., Zanini, M. A., San José, J. T. & Pellegrino, C. Bond between steel reinforcement bars and electric arc furnace slag concrete. Mater. Struct. 50, 170 (2017).

Zuaiter, M., El-Hassan, H., El-Maaddawy, T. & El-Ariss, B. Properties of slag-fly ash blended geopolymer concrete reinforced with hybrid glass fibers. Buildings 12, 1114 (2022).

Ozbakkaloglu, T., Gu, L. & Fallah Pour, A. Normal- and high-strength concretes incorporating air-cooled blast furnace slag coarse aggregates: Effect of slag size and content on the behavior. Constr. Build. Mater. 126, 138–146 (2016).

Rojas, N., Bustamante, M., Muñoz, P., Godoy, K. & Letelier, V. Study of properties and behavior of concrete containing EAF slag as coarse aggregate. Dev. Built Environ. 14, 100137 (2023).

Coppola, L., Buoso, A., Coffetti, D., Kara, P. & Lorenzi, S. Electric arc furnace granulated slag for sustainable concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 123, 115–119 (2016).

Mohamed, O. A., Najm, O. & Ahmed, E. Alkali-activated slag & fly Ash as sustainable alternatives to OPC: Sorptivity and strength development characteristics of mortar. Clean. Mater. 8, 100188 (2023).

Mohamed, O. A., Ati, M. & Najm, O. F. Predicting compressive strength of sustainable Self-Consolidating concrete using random forest. Key Eng. Mater. 744, 141–145 (2017).

ASTM C150/C150M-22. Specification for Portland Cement. Preprint at (2022). https://doi.org/10.1520/C0150_C0150M-22.

ASTM C114-09. Test Methods for Chemical Analysis of Hydraulic Cement. Preprint at (2009). https://doi.org/10.1520/C0114-09.

EN 196-3:2016. Methods of testing cement – Part 3: Determination of setting times and soundness. https://doi.org/10.3403/30338529 (2016).

ASTM C127-24. Test Method for Relative Density (Specific Gravity) and Absorption of Coarse Aggregate. Preprint at (2024). https://doi.org/10.1520/C0127-24

U.S. Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration. Use of Air-Cooled Blast Furnace Slag as Coarse Aggregate in Concrete Pavements— A Guide to Best Practice (FHWA-HIF-12-009). (2012).

ASTM C136-01. Test Method for Sieve Analysis of Fine and Coarse Aggregates. Preprint at (2001). https://doi.org/10.1520/C0136-01.

BS 8500-2. Specification For Constituent Materials and Concrete. (2015).

ASTM C192/C192M-14. Practice for Making and Curing Concrete Test Specimens in the Laboratory. Preprint at (2014). https://doi.org/10.1520/C0192_C0192M-14

ASTM C143/C143M. Test Method for Slump of Hydraulic-Cement Concrete. Preprint at (2012). https://doi.org/10.1520/C0143_C0143M-12

Santamaría, A. et al. Self-compacting concrete incorporating electric arc-furnace steelmaking slag as aggregate. Mater. Des. 115, 179–193 (2017).

British Standards Institution (BSI). Testing Concrete – Methods for Analysis of Hardened Concrete (BS 1881 – 211:2016)). (2015).

Rilem RILEM Technical Recommendations for the Testing and Use of Construction Materials (CRC, 1994). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781482271362

BS EN 12390-8. Testing hardened concrete. Depth of penetration of water under pressure. https://doi.org/10.3403/30360076U (2019).

ASTM C1202-19. Test Method for Electrical Indication of Concretes Ability to Resist Chloride Ion Penetration. https://doi.org/10.1520/C1202-19

Torréns-Martín, D. & Fernández-Carrasco, L. Effect of sulfate content on cement mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 48, 144–150 (2013).

British Standards Institution (BSI). Testing Hardened Concrete – Part 2: Making and Curing Specimens for Strength Tests (BS EN 12390-2:2019). (2019).

British Standards Institution (BSI). Testing Concrete – Method for Determination of Tensile Splitting Strength (BS 1881 – 117:1983). (1983).

Wang, A. et al. Application of air-cooled blast furnace slag aggregates as replacement of natural aggregates in cement-based materials: A study on water absorption property. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol.-Mater. Sci. Ed. 33, 445–451 (2018).

Yoo, J. H., Lee, H. S. & Ismail, M. A. An analytical study on the water penetration and diffusion into concrete under water pressure. Constr. Build. Mater. 25, 99–108 (2011).

British Standards Institution. BS 1881 – 124: Testing Concrete—Methods for Determination of Flexural Strength. (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs (ORSP) at Abu Dhabi University. Tae-Yeon Kim and Mohammad Zuaiter acknowledge the financial support provided by Khalifa University of Science & Technology and Advanced Digital & Additive Manufacturing (ADAM) Group (No. 8474000163).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O. A. and M.Z. wrote the main manuscript. A. H., O. G., and M.Z. conducted experiments. A. H. , O.G., and M.Z. prepared figures. T.K. reviewed the manuscript. O. A. and T.K secured funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohamed, O.A., Ghanam, O., Hamdan, A. et al. Mechanical properties and durability of concrete with recycled air-cooled blast furnace slag aggregates. Sci Rep 15, 24384 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09242-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09242-1