Abstract

There is a known association between socioeconomic status (SES) and increased mortality risk in individuals with diabetes and its pre-diabetic state. Depression has been identified as a significant risk factor for mortality in populations with low SES. this study aims to gain a deeper Understanding of the relationship between SES and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk in individuals with diabetes and its pre-diabetic state by exploring the mediating role of depression. This study included 17,823 participants who participated in the National health and nutrition examination survey (NHANES) between 2005 and 2018. Weighted multivariate COX regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the association between SES and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk in individuals with diabetes and its pre-diabetic state. Additionally, mediation analysis was performed to explore the mediating role of depression. After adjusting for multiple variables, low SES was associated with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.71 (95% CI: 1.42–2.02; P < 0.0001) for all-cause mortality risk and an HR of 1.88 (95% CI: 1.35–2.63; P < 0.001) for cardiovascular mortality risk in individuals with diabetes and its pre-diabetic state. Furthermore, after adjusting for multiple variables, depression was associated with an HR of 1.51 (95% CI: 1.28–1.79; P < 0.0001) for all-cause mortality risk and an HR of 1.64 (95% CI: 1.18–2.27; P = 0.003) for cardiovascular mortality risk. Mediation model results revealed that after complete adjustment, depression accounted for 10.34% of the mediating effect of the relationship between SES and all-cause mortality risk in individuals with diabetes and its pre-diabetic state, and 9.30% of the mediating effect of the relationship between SES and cardiovascular mortality risk. Identifying individuals with depression and providing appropriate treatment May lower the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality associated with diabetes and its pre-diabetic state in the low SES population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes and its pre-diabetic state are closely associated with a significant increase in all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates, and these patients typically have poor prognosis1,2. Therefore, it is important to study the risk factors for mortality in patients with diabetes and its pre-diabetic state in depth. Studies have shown that SES is one of the important factors that influence the health outcomes of patients with diabetes and its pre-diabetic state3. Low SES is often associated with poor health behaviors, limited access to medical resources, and greater psychological stress, all of which may increase the risk of mortality in patients with diabetes. Additionally, depression, as a prevalent mental health issue, may serve as a mediator between socioeconomic status (SES) and mortality risk. Specifically, depression not only significantly reduces the quality of life for patients but also negatively impacts health through multiple pathways, such as impairing patients’ self-management abilities4, reducing treatment adherence, and prompting unhealthy lifestyle choices. These factors work together, ultimately leading to the deterioration of diabetes, increased risk of complications, and higher mortality rates among patients5,6,7,8,9.Low SES may limit individuals’ access to quality education, healthcare, and nutritious food, increasing psychological stress and feelings of social isolation, thus reducing their quality of life. However, the quality of life is also influenced by other factors, such as individual personality, social support systems, and coping abilities10.

Previous studies have shown a significant positive correlation between lower SES and the incidence of depression11. Depression not only has a negative impact on individual psychological health, but is also considered an important intermediary factor in the increased mortality rate of patients with diabetes12.This complex mechanism involves both physiological and psychological aspects: The life stress and lack of social support associated with low SES may exacerbate depressive symptoms, increasing the psychological burden on patients. As a mediating factor, depression may increase the mortality risk of diabetes patients by negatively impacting cardiovascular health and metabolic control. Specifically, depression may lead to unhealthy lifestyle habits in patients, such as poor diet, lack of exercise, smoking, and excessive drinking, all of which can impair cardiovascular health and metabolic control. These results suggest that this bidirectional negative impact will increase the burden of disease management to a greater extent when interventions are administered to people with diabetes because behavior also impacts mental health13. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the dual impact of SES and mental health in order to more effectively reduce the risk of mortality and improve overall health14,15. However, there is currently no systematic study to verify the mediating role of depression in the association between SES and diabetes and its pre-diabetic state, as well as all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk. Therefore, in-depth exploration of this mediating mechanism would enhance the targeting and effectiveness of clinical interventions.To verify the potential mediating role of depression in this study, we first assessed the association between depression and the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. This step is necessary because depression can only serve as a mediator between SES and mortality if it is itself a risk factor for mortality. Furthermore, quantifying the degree of impact that depression has on mortality helps us evaluate its mediating effect within the model of this study.

The aim of this study is to address the limited evidence gap regarding the association between SES, depression, diabetes, its pre-diabetic state, and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates. Specifically, the main objective of this study is to verify the association between SES and diabetes and its pre-diabetic state with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates. Additionally, this study will analyze how depression impacts the association between diabetes, its pre-diabetic state, and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates, as well as the role SES plays in this process. Furthermore, this study will thoroughly assess the mediating effect of depression on the association between SES, diabetes, its pre-diabetic state, and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates. This study is the first to investigate the mediating effect of depression on the association between SES, diabetes, its pre-diabetic state, and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates, providing potential clinical benefits for reducing the mortality risk of patients with diabetes and its pre-diabetic state and related risk management.

Method

Data source

The data for this study were obtained from seven NHANES data cycles spanning from 2005 to 2018. NHANES is a continuous cross-sectional observational study aimed at collecting health data from a representative sample of non-institutionalized individuals in the United States. The study protocol has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), and all participants have provided their informed consent.The Ethics Committee of Xuancheng People’s Hospital has exempted this study from ethical approval requirements.While NHANES is a cross-sectional survey, our study utilized longitudinal data from multiple NHANES cycles (2005–2018) linked with mortality data up to December 31, 2019. This allowed us to conduct a cohort study design, examining the impact of SES and depression on long-term mortality risk and exploring the mediating role of depression over time.

Study design and population

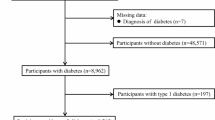

Our study involved 39,251 participants aged ≥ 18 years between 2005 and 2018.The exclusion criteria for analysis included participants who at any point during the study period (2005–2018) lacked data on diabetes and its pre-diabetic state (n = 15,572), lacked data on PHQ-9 score (n = 2163), lacked data on the family poverty income ratio (PIR) (n = 1,804), lacked demographic information (n = 1,156) including age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, smoking, alcohol use, hypertension, coronary heart disease (CHD), and BMI, lacked laboratory data (n = 730), or lacked follow-up time data (n = 3).Ultimately, the analysis included 17,823 eligible participants, as shown in Fig. 1.

Definition of associated assssment

Assessment of depression

In this study, the PHQ-9 was used to assess depression outcomes. The questionnaire is a brief screening tool that can effectively evaluate the severity of depression symptoms (116). The PHQ-9 uses a 0–3 scoring system based on the DSM-5 criteria17, with a total score range of 0–2718. In this study, a cutoff value of 10 or higher on PHQ-9 was used to identify depression, and the severity of depression was further classified as none (0–4), mild5,6,7,8,9, moderate10,11,12,13,14, moderately severe15,16,17,18,19, and severe (≥ 20)19. During the use of PHQ-9, it was validated and found to be consistent with DSM-5 criteria.

Assessment of household PIR and SES

The Health and Human Services poverty guidelines were used in this study to calculate participants’ family PIR, which reflects an individual’s socioeconomic status20.Specifically, PIR is calculated by dividing family income by a specific poverty criterion. PIR = Family income / Poverty guidelines. The poverty guidelines are based on the Health and Human Services poverty guidelines, which is based on family size and year. If the family income is reported as category ranges, the calculation of PIR uses the midpoint.It should be noted that reports of PIR values greater than or equal to 5.0 were recorded as 5.0 due to disclosure issues and to protect the privacy of high-income participants, as per NHANES guidelines. Additionally, based on the family PIR, income levels were classified into low, medium, and high categories, with 1.3 and 3.5 used as the cut-off values. These cut-off values are consistent with previous NHANES studies and are commonly used to define low, middle, and high socioeconomic status groups19.

Assessment of diabetes and prediabetes

In this study, the definition of diabetes was based on the following criteria: Participants were considered to have diabetes if they met any of the following criteria: fasting blood glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test level ≥ 11.1 mmol/L; random blood glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol/L; glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥ 6.5%; or confirmation through the use of diabetes medication or insulin or diagnosis by a physician21. The criteria for defining pre-diabetes include: fasting blood glucose in the range of 5.6-7 mmol/L or 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test results between 7.8 and 11 mmol/L; HbA1c level ≥ 5.7% and < 6.5%; or confirmation by a physician as pre-diabetes22. This definition incorporates both biomarker data and self-reported diagnoses to ensure a comprehensive assessment of diabetes and prediabetes status.

Death related information

The primary objective of this study was to investigate outcomes such as all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease mortality. To determine patient mortality, we linked mortality information for NHANES participants from 2005 to 2018 with death record data from the National Death Index and used a probabilistic matching algorithm for matching. Additionally, to estimate cardiovascular disease mortality rates, we applied the coding range in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) which includes codes from I00-I09, I11, I13, I20-I51, and I60-I69.Due to the complex sampling design of NHANES and the varying entry times of participants, it is not possible to calculate a precise median follow-up time for the entire cohort, our endpoint was patient death or December 31, 2019.

Covariates

To ensure that factors related to mortality in patients with diabetes or pre-diabetes were fully considered in this study, multiple covariates were included based on previous research and clinical experience. These covariates included age, sex, race, education level, marital status, hypertension, body mass index (BMI), smoking, and alcohol consumption.

In order to provide more detailed classification methods for the relevant variables used in this study, we have explained each of these variables in specific terms. With respect to race, this includes non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic whites, Mexican Americans, and others. PIR was divided into three categories: less than 1.3, 1.3–3.3, and greater than 3.5. Marriage status was classified as married, divorced, unmarried, or other. Additionally, for smoking status, we established three different categories: ① smoking less than 100 cigarettes during a lifetime was defined as never having smoked; ② smoking more than 100 cigarettes during a lifetime, but not currently smoking at all, was defined as having smoked in the past; and ③ smoking more than 100 cigarettes during a lifetime and currently smoking occasionally or daily, was defined as current smokers. Regarding alcohol consumption, we divided it into five categories: never drank (less than 12 times in a lifetime), quit drinking (12 or more times in a year but not in the previous year, or not in the previous year but had 12 or more times in a lifetime), heavy drinking (3 or more drinks per day for women / 4 or more drinks per day for men or drinking 5 or more days per month), moderate drinking (2 or more drinks per day for women / 3 or more drinks per day for men, or binge drinking 2 or more days per month), and mild drinking (none of the above). Finally, Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by height squared (m2), where a BMI less than 25 kg/m2 is considered normal, 25 kg/m2 to 30 kg/m2 is overweight, and greater than 30 kg/m2 is obese. It is important to note that weight and height measurements in NHANES are collected by trained interviewers using standardized equipment, ensuring a high level of accuracy.

In addition, we conducted laboratory tests on the participants, including measurements of creatinine, uric acid, blood urea nitrogen, lymphocytes, neutrophils, hemoglobin, platelets, and HbA1c.

Statistical analysis

This study performed data analysis using R software (version 4.3.2). In the analysis process, we followed the recommendations of the NHANES Analysis and Reporting Guidelines and considered the complex sampling design and sampling weights. In the weighted analysis, we used the MEC sample weight (WTMEC2YR/7) for data processing. SES was divided into Low, Middle, and High groups based on PIR; depression status was divided into five groups: none (0–4), mild5,6,7,8,9, moderate10,11,12,13,14, moderately severe15,16,17,18,19, and severe (≥ 20) based on PHQ-9 scores. Mean (SE) was used to represent continuous variables, while frequency (%) was used for categorical variables.

We used a multivariable weighted logistic Cox regression model to investigate the relationship between SES and the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes. We also examined the relationship between depression and each symptom of depression with the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes. Multivariable weighted linear regression was used to evaluate the relationship between PIR and the PHQ-9 total score. Model 1 was an unadjusted model. Model 2 adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity. Model 3 further adjusted for marital status, education, smoking and drinking status, hypertension, coronary heart disease, and BMI.At the same time, we assessed the relationship between SES and the risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes and prediabetes.

We used restricted cubic spline (RCS) analysis to evaluate the potential nonlinear/linear relationship between PIR and the PHQ-9 score with the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes. Additionally, we further explored the potential mediating role of PHQ-9 in the association between PIR and the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes. Sensitivity analyses included subgroup analyses based on age, sex, race/ethnicity, BMI, hypertension, and coronary heart disease. Furthermore, Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests were used to evaluate the relationship between SES categories and the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 1 presents the characteristics of participants. The final dataset included 17,823 participants, with a weighted mean age of 51.29 (0.28) years. Approximately 68.71% of the participants were non-Hispanic whites. Furthermore, 58.18% of the participants had received a college degree or higher education, and 58.98% lived with a spouse/partner. The participants had a weighted mean PIR of 3.04 ± 0.03, with around 20.64% of the participants coming from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Participants with lower socioeconomic status had higher PHQ-9 scores and a greater risk of moderate-to-severe depression. Moreover, participants with lower socioeconomic status had a higher risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

Relationship between SES and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes

Table 2 presents the risk assessment results of the association between SES and the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes. In model 3, we found that PIR, as a continuous variable, was significantly negatively correlated with the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes. Specifically, for every one-unit increase in PIR, the risk of all-cause mortality decreased by approximately 14% (HR, 0.86; 95% CI: 0.82–0.90, P < 0.0001). Moreover, compared with high SES participants, low SES participants had a 71% increase in the risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 1.71; 95% CI: 1.45–2.02, P < 0.0001). For every one-unit increase in PIR, the risk of cardiovascular mortality decreased by approximately 16% (HR, 0.84; 95% CI: 0.77–0.92, P < 0.0001). Similarly, low SES participants had an 88% increase in the risk of cardiovascular mortality (HR, 1.88; 95% CI: 1.35–2.63, P < 0.001), compared with high SES participants. As shown in Fig. 2A, multivariable-adjusted RCS analysis indicated a nonlinear correlation between PIR and the risk of all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes (nonlinear P < 0.05). On the other hand, as shown in Fig. 2B, multivariable-adjusted RCS analysis indicated a linear correlation between PIR and the risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes (nonlinear P > 0.05). As shown in Fig. 3, multivariable-adjusted Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank tests also confirmed the association between low SES participants and increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality (P < 0.05).

Association between household poverty income ratio(PIR) and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes and prediabetes in restricted cubic spline models.(A)All-causemortality; (B)Cardiovascular Mortality.Adjusted for Age, Sex, Race, Smoke, Alcohol, Hypertension, Marital, BMI, CHD, Education.

The relationship between SES and the risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in diabetes and prediabetes patients

Supplementary Table 3 presents the risk assessment results of the association between SES and all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in diabetes patients. In Model 3, we found that PIR, as a continuous variable, was associated with a approximately 14% reduction in all-cause mortality risk for each 1-unit increase (HR, 0.86; 95% CI: 0.81–0.91, P < 0.0001). Additionally, compared to high SES participants, low SES participants had a 75% increased risk of all-cause mortality (HR, 1.75; 95% CI: 1.44–2.13, P < 0.0001). For each 1-unit increase in PIR, the risk of cardiovascular mortality decreased by approximately 19% (HR, 0.81; 95% CI: 0.73–0.91, P < 0.001). Similarly, low SES participants had a 115% increased risk of cardiovascular mortality (HR, 2.15; 95% CI: 1.39–3.31, P < 0.001).

Supplementary Table 4 presents the risk assessment results of the association between SES and the risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in prediabetes patients. In Model 3, with PIR treated as a continuous variable, each 1-unit increase in PIR is associated with approximately a 10% reduction in all-cause mortality risk (HR, 0.90; 95% CI: 0.84–0.96, P = 0.003). Additionally, compared to participants with high SES, those with low SES have a 52% increase in all-cause mortality risk (HR, 1.52; 95% CI: 1.15–2.01, P = 0.003). Each 1-unit increase in PIR is associated with a roughly 15% reduction in cardiovascular mortality risk (HR, 0.85; 95% CI: 0.75–0.97, P = 0.01). Similarly, low SES participants exhibit an 88% increase in cardiovascular mortality risk (HR, 1.88; 95% CI: 1.13–3.13, P = 0.02).

Relationship between PHQ-9 score and depressive status and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality

Supplementary Table 1 provides the assessment results of the association between PHQ-9 scores, depressive status, and the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes. In model 3, we observed that for every one-point increase in PHQ-9 scores, the HR for all-cause mortality risk was 1.04 (95% CI: 1.03–1.06), and the HR for all-cause mortality risk in patients with depressive status was 1.51 (95% CI: 1.28–1.79). Further analysis revealed that compared with non-mild depression, mild, moderate, moderately-severe, and severe depression increased the risk of all-cause mortality by 38%, 49%, 93%, and 85%, respectively. Similarly, in the analysis of cardiovascular mortality risk, for every one-point increase in PHQ-9 scores, the HR for cardiovascular mortality risk was 1.04 (95% CI: 1.02–1.07), and the HR for all-cause mortality risk in patients with depressive status was 1.64 (95% CI: 1.18–2.27). Further analysis showed that compared with non-mild depression, mild, moderate, and moderately-severe depression increased the risk of all-cause mortality by 45%, 85%, and 88%, respectively. Additionally, Supplementary Fig. 1A showed that multivariable-adjusted RCS analysis indicated a linear correlation between PHQ-9 scores and the risk of all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes (nonlinear P > 0.05). On the other hand, Supplementary Fig. 1B showed that multivariable-adjusted RCS analysis indicated a nonlinear correlation between PHQ-9 scores and the risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes (nonlinear P < 0.05).These results indicate that depression is an important predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk in patients with diabetes and prediabetes, providing a basis for our subsequent exploration of the mediating role of depression in the relationship between SES and mortality.

Relationship between PHQ-9 score and SES

Supplementary Table 2 presents the risk assessment results of the association between PHQ-9 scores and SES. After comprehensive adjustment for potential confounders, we found that for each one-unit increase in PIR, there was a negative correlation with PHQ-9 scores in terms of the risk of all-cause mortality, with a β coefficient of -0.38 (95% CI: -0.43,-0.33). Compared with participants of high SES, the β coefficients for participants of middle and low SES were 0.60 (95% CI: 0.42, 0.77) and 1.49 (95% CI: 1.28, 1.70), respectively. For the risk of cardiovascular mortality, every one-unit increase in PIR was also negatively correlated with PHQ-9 scores, with a β coefficient of -0.38 (95% CI: -0.43,-0.32). The β coefficients for participants of middle and low SES were 0.63 (95% CI: 0.43, 0.82) and 1.46 (95% CI: 1.24, 1.67), respectively.

Mediation analysis and subgroup analysis

Figure 4 shows that PHQ-9 had a significant mediating effect (mediation proportion: 10.34%, total effect: 30.92, P < 0.0001) in the association between PIR and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes. Similarly, in the association between PIR and all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes, PHQ-9 also showed a significant mediating effect (mediation proportion: 9.30%, total effect: 211.18, P < 0.0001). In addition, in the subgroup analysis of the risk of all-cause mortality, we observed a significant interaction with age (P < 0.05) (Table 3). Moreover, in the risk analysis of cardiovascular mortality, we found a significant interaction between age and race (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

Discussion

In our study, we demonstrated a negative correlation between PIR, SES and the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes. Concurrently, we confirmed that depression and its severity were negatively associated with SES and positively associated with the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes. RCS results showed that PIR had a non-linear correlation with the risk of all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes (nonlinear P < 0.05) and a linear correlation with the risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes (nonlinear P > 0.05). The K-M survival curve and Log-Rank test showed that the risk of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality was higher in participants of low SES than in those of high SES (P < 0.05). Based on these findings, after adjusting for all potential confounding factors, we further identified that up to 10.34% of the association between SES and the risk of all-cause mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes was mediated by depression; 9.30% of the association between SES and the risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes was mediated by depression.

In today’s society, diabetes has become a global public health problem, and with the development of the social economy, the incidence of diabetes is constantly increasing23. At the same time, relevant studies have shown that socioeconomic factors play a crucial role in the health outcomes of patients with diabetes24. The results of this study further reveal the complex relationships between SES, depression, diabetes and its prediabetic state, and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, providing important insights into understanding the health disparities of patients with diabetes.

Studies exploring the impact of SES on population health have shown a significant association between low SES and higher all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates, which our findings further validate. By comparing patients of different SES levels, we found that those with low SES not only face a higher risk of mortality, but also exhibit significant disadvantages in terms of health behaviors and lifestyles. For example, people with low SES often struggle to access healthcare services, consistent with findings from multiple studies suggesting that low SES not only restricts access to healthcare resources, but may also directly impact health outcomes by influencing individual behaviors such as diet and exercise25,26. In addition, low SES is closely related to the deterioration of mental health, particularly in the significantly increased incidence of depression among low SES populations, which deserves further exploration. Compared to previous research, our study further emphasizes the multidimensional impact of SES on health outcomes, particularly in terms of mental health. Previous literature suggests that low SES not only leads to physiological health problems, but can also exacerbate health inequalities through the deterioration of mental health27,28. For example, Komura et al. found in their study on American adults that the relationship between education level and risk of death was particularly pronounced in patients with diabetes, emphasizing the importance of education and SES in health management29. Furthermore, Morton et al.pointed out in their study of myocardial infarction patients that SES plays a key role in patient rehospitalization and mortality rates, further supporting the complex relationship between SES and health outcomes30.

Depression is widely recognized as a significant factor in the health management of patients with diabetes, particularly in patients of low SES where this relationship is even more pronounced. Depression affects diabetes management in multiple ways, including reducing patients’ self-management abilities, decreasing treatment adherence, and increasing the incidence of unhealthy habits such as smoking and alcohol consumption. Consistent with previous research findings, the latter also emphasizes the negative impact of depression on the health outcomes of patients with diabetes31,32. For example, some studies suggest that depression not only affects patients’ psychological status, but may also exacerbate diabetes complications through physiological mechanisms, thereby increasing overall and cardiovascular mortality rates33,34. Compared to previous literature, our study further emphasizes the importance of depression in the comprehensive management of patients with diabetes, particularly in the low SES population. Previous research has indicated that low SES patients generally have poor mental health conditions and significantly increased incidence of depression, which may lead to difficulties in disease management35,36. For example, studies indicate that low SES patients face greater psychological health challenges in diabetes management, further impacting their treatment compliance and health outcomes37. Additionally, research emphasizes that implementing psychological interventions for depression can effectively improve the overall health status of patients with diabetes, thereby reducing the risk of death38. Depression plays a crucial role in the health management of patients with diabetes, especially in those of low SES. Our study not only validates some of the findings from previous literature, but also provides new perspectives for clinical practice, suggesting that psychological health interventions should be incorporated into routine treatment strategies for patients with diabetes to promote their overall health and quality of life.

The findings of this study have both similarities and differences in multiple aspects from previously published literature. First, this study emphasizes the significant impact of SES on overall and cardiovascular mortality risk, particularly in the middle and low SES populations. Specifically, the study results show that for each 1-unit increase in the PIR, there is a negative correlation with PHQ-9 scores, indicating a correlation between higher SES and lower depressive symptoms, which is consistent with the conclusions of previous literature, which also pointed out the impact of SES on mental health and mortality risk39,40. For example, some studies suggest that depression symptoms are more severe in low SES individuals, and their risk of death is significantly higher than in high SES individuals41,42.

However, the unique aspect of this study lies in its full adjustment for confounding factors, providing more precise β value estimates. For overall mortality risk, the β for each 1-unit increase in PIR is -0.38 (95% CI: -0.43, -0.33), while in cardiovascular mortality risk, the β is also − 0.38 (95% CI: -0.43, -0.32). In addition, for participants of middle and low SES, the β values adjusted in Model 3 compared to those in high SES participants are 0.60 (95% CI: 0.42, 0.77) and 1.49 (95% CI: 1.28, 1.70), respectively, displaying significant differences in the impact of SES on mortality risk at different income levels. This finding further supports the importance of SES in health outcomes, particularly in the field of cardiovascular disease and mental health studies43,44. This study not only validates the relationship between SES and mortality risk, but also provides a more detailed analysis through the control of confounding factors, emphasizing the importance of psychological health interventions in different SES groups. These results provide important reference for future public health policies, especially in the implementation of health intervention measures for low SES diabetes or pre-diabetes patients.

The subgroup analysis results of this study indicate that age has a significant interaction effect on all-cause mortality risk (P < 0.05); there is also a significant interaction effect between age and race on cardiovascular mortality risk (P < 0.05). These findings suggest that age and race may play important roles in the relationship between socioeconomic status (SES) and mortality. Age may influence an individual’s exposure to and susceptibility to SES-related risk factors43. For instance, older adults may be more adversely affected by low SES due to declining physiological reserve and increased prevalence of chronic diseases. Additionally, older individuals may experience higher levels of social isolation and loneliness, factors that can also elevate their mortality risk45.At the same time, race may be associated with cultural factors, socioeconomic status, discrimination within the healthcare system, and other elements46. Different racial groups may face varying barriers to accessing healthcare resources, educational opportunities, and employment. Long-standing racial discrimination and social injustices may lead to chronic stress and psychological burdens, thereby increasing the risk of cardiovascular diseases47. These interactions suggest that tailored intervention strategies are needed to reduce SES-related mortality risk for different age and racial groups. For example, for older adults, enhancing social support and healthcare services should be prioritized; for minority groups, eliminating discrimination within the healthcare system and improving access to quality medical care are essential. Future research should further explore the specific mechanisms through which age and race influence the relationship between SES and mortality to develop more effective intervention strategies.

This study has several strengths. First, it utilizes a large, nationally representative sample from NHANES, enhancing the generalizability of our findings. Second, we employed rigorous statistical methods, including weighted multivariate Cox regression and mediation analysis, to account for complex survey design and potential confounding factors. Third, our study provides novel insights into the mediating role of depression in the relationship between SES and mortality in individuals with diabetes and prediabetes, highlighting a potential pathway for intervention.

However, some limitations should be acknowledged.First, although our study utilized longitudinal data, the observational nature of the study limits our ability to definitively establish causal interpretations of our results and the temporal priority of the mediation. Future studies with experimental designs are needed to confirm these findings. Second, the CVD patient data included in this study were extracted from NHANES health examinations, and the relevant variables were mainly based on self-reports, which may have introduced some subjective biases in patients, affecting the accuracy and objectivity of the data. Third, the participants in this study were only adult patients from the United States, and therefore, further research is needed to determine whether the conclusions are applicable to other populations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that depression mediates the relationship between socioeconomic status and both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in individuals with diabetes and prediabetes. Specifically, low SES is associated with increased depression, which in turn elevates the risk of mortality. These findings highlight the critical need for integrated interventions that address both socioeconomic disparities and mental health in this vulnerable population. By identifying and treating depression, we can potentially reduce mortality risks and improve overall health outcomes for individuals with diabetes and prediabetes from low SES backgrounds. Future research should focus on developing and evaluating targeted interventions that address these intertwined factors.

Data availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its supplementary data or in the publicly available NHANES database (cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes).

6.References

Ding, L. et al. The prognostic value of the stress hyperglycemia ratio for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes or prediabetes: insights from NHANES 2005–2018. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 23 (1), 84 (2024).

Huang, Y., Cai, X., Mai, W., Li, M. & Hu, Y. Association between prediabetes and risk of cardiovascular disease and all cause mortality: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical Res. ed). 355, i5953 (2016).

Wu, H., Meng, X., Wild, S. H., Gasevic, D. & Jackson, C. A. Socioeconomic status and prevalence of type 2 diabetes in Mainland china, Hong Kong and taiwan: A systematic review. J. Global Health. 7 (1), 011103 (2017).

Huang, J., Peng, D. & Wang, X. Estimating the impact of metabolic syndrome on low back pain and the joint effects of metabolic syndrome and depressive symptoms on low back pain: insights from the China health and retirement longitudinal study. BMC Public. Health. 24 (1), 2359 (2024).

Pathirana, M. M. et al. Anxiety and depression in early gestation and the association with subsequent gestational diabetes mellitus in a disadvantaged population. Matern. Child Health J. 27 (12), 2185–2193 (2023).

Jaatinen, N., Jääskeläinen, T., Laivuori, H. & Ekholm, E. The non-traditional and Familial risk factors for preeclampsia in the FINNPEC cohort. Pregnancy Hypertens. 23, 48–55 (2021).

Huang, J. & Wang, X. Association of depressive symptoms with risk of incidence low back pain in middle-aged and older Chinese adults. J. Affect. Disord. 354, 627–633 (2024).

White, J. et al. Duration of depressive symptoms and mortality risk: the english longitudinal study of ageing (ELSA). Br. J. Psychiatry. 208 (4), 337–342 (2016).

Robinson, R. G. & Jorge, R. E. Post-Stroke depression: A review. Am. J. Psychiatry. 173 (3), 221–231 (2016).

Liu, R., Huang, J., Cai, L., Qiu, W. & Liu, X. The moderating effect of family socioeconomic status in the relationship between health-related behaviors and quality of life among the Hakka older adults in fujian, China. Qual. Life Res. (2025).

Li, W., Ruan, W., Peng, Y., Lu, Z. & Wang, D. Associations of socioeconomic status and sleep disorder with depression among US adults. J. Affect. Disord. 295, 21–27 (2021).

Lara-Cinisomo, S., Loret de Mola, J. R., Flores-Carter, K., Tabb, K. M. & Roloff, K. Prenatal depressive symptoms, Self-Rated health, and diabetes Self-Efficacy: A moderated mediation analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health ;19(20). (2022).

Dong, Y., Huang, J. & Liu, H. Independent and joint associations of dietary diversity and physical activity on mental health among older adults in china: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public. Health. 25 (1), 599 (2025).

Rayport, Y. K. et al. Associations of adverse maternal experiences and diabetes on postnatal maternal depression and child social-emotional outcomes in a South African community cohort. PLOS Global Public. Health. 2 (10), e0001124 (2022).

Krzeczkowski, J. E. et al. Maternal metabolic complications in pregnancy and offspring behavior problems at 2 years of age. Matern. Child Health J. 23 (6), 746–755 (2019).

Battle, D. E. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM). CoDAS 25 (2), 191–192 (2013).

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16 (9), 606–613 (2001).

Levis, B., Benedetti, A. & Thombs, B. D. Accuracy of patient health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical Res. ed). 365, l1476 (2019).

Hua, J. et al. The mediating role of depression in the association between socioeconomic status and cardiovascular disease: A nationwide cross-sectional study from NHANES 2005–2018. J. Affect. Disord. 366, 466–473 (2024).

Cowan, A. E. et al. Dietary supplement use differs by socioeconomic and Health-Related characteristics among U.S. Adults, NHANES 2011⁻2014. Nutrients ;10(8). (2018).

Xu, Z. et al. Association between the oxidative balance score and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in patients with diabetes and prediabetes. Redox Biol. 76, 103327 (2024).

Yu, B. et al. The non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHHR) as a predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in US adults with diabetes or prediabetes: NHANES 1999–2018. BMC Med. 22 (1), 317 (2024).

Santos Martín, M. T., Gómez Santos, E., Torres Del Pino, M., Muñoz-Cobo G. T. & Pérez Hernández A. Gestational and pregestational diabetes: perinatal characteristics and neonatal morbidity. An. Pediatr. 96 (2), 158–160 (2022).

Shrivastava, U., Misra, A., Gupta, R. & Viswanathan, V. Socioeconomic factors relating to diabetes and its management in India. J. Diabetes. 8 (1), 12–23 (2016).

Jalili, F., Hajizadeh, M., Mehrabani, S., Ghoreishy, S. M. & MacIsaac, F. The association between neighborhood socioeconomic status and the risk of incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 1,678,582 participants. Cancer Epidemiol. 91, 102598 (2024).

Roy, T. & Lloyd, C. E. Epidemiology of depression and diabetes: A systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 142 (Suppl), S8–21 (2012).

Zang, E. & Bardo, A. R. Objective and subjective socioeconomic status, their discrepancy, and health: evidence from East Asia. Soc. Indic. Res. 143 (2), 765–794 (2019).

Schultz, W. M. et al. Socioeconomic status and cardiovascular outcomes: challenges and interventions. Circulation 137 (20), 2166–2178 (2018).

Komura, T., Kondo, N., Bhatt, K. & Inoue, K. Association between educational status and mortality according to diabetes status among US adults. Mayo Clin. Proc. Innovations Qual. Outcomes. 7 (4), 203–211 (2023).

Morton, J. I. et al. Treatment gaps, 1-year readmission and mortality following myocardial infarction by diabetes status, sex and socioeconomic disadvantage. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health. 76 (7), 637–645 (2022).

Celik, A., Forde, R. & Sturt, J. The impact of online self-management interventions on midlife adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Br. J. Nurs. 29 (5), 266–272 (2020).

Basiri, R., Seidu, B. & Rudich, M. Exploring the interrelationships between diabetes, nutrition, anxiety, and depression: implications for treatment and prevention strategies. Nutrients 15, 19 (2023).

Huang, J. H., Li, R. H. & Tsai, L. C. Relationship between depression with physical activity and obesity in older diabetes patients: inflammation as a mediator. Nutrients 14, 19 (2022).

Conley, N. Social determinants of health, chronic disease management, and the role of the primary care Provider-to include cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, major causes of morbidity and mortality as affected by social determinants of health. Prim. Care. 50 (4), 671–678 (2023).

Reiss, F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 90, 24–31 (2013).

Tzur Bitan, D., Berzin, D., Kridin, K. & Cohen, A. The association between alopecia areata and anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder: a population-based study. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 314 (5), 463–468 (2022).

Ahsan, K. Z. et al. Socioeconomic disparities in diabetes prevalence and management among the adult population in Bangladesh. PloS One. 17 (12), e0279228 (2022).

González-Burboa, A. et al. [Psychological interventions for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. A systematic review and meta-analysis]. Rev. Med. Chil. 147 (11), 1423–1436 (2019).

Dugravot, A. et al. Social inequalities in multimorbidity, frailty, disability, and transitions to mortality: a 24-year follow-up of the Whitehall II cohort study. Lancet Public. Health. 5 (1), e42–e50 (2020).

Cui, Y. et al. Associations of depressive symptoms with All-Cause and Cause-Specific mortality by race in a population of low socioeconomic status: A report from the Southern community cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 190 (4), 562–575 (2021).

Berk, M. et al. Comorbidity between major depressive disorder and physical diseases: A comprehensive review of epidemiology, mechanisms and management. World Psychiatry: Official J. World Psychiatric Association (WPA). 22 (3), 366–387 (2023).

Miller, N. E., Fisher, A., Frank, P., Lally, P. & Steptoe, A. Depressive symptoms, socioeconomic position, and mortality in older people living with and beyond Cancer. Psychosom. Med. 86 (6), 523–530 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. The associations of socioeconomic status, social activities, and loneliness with depressive symptoms in adults aged 50 years and older across 24 countries: findings from five prospective cohort studies. Lancet Healthy Longev. 5 (9), 100618 (2024).

Liu, Q. et al. Adherence to prescribed antihypertensive medication among patients with depression in the united States. BMC Psychiatry. 22 (1), 764 (2022).

Lai, E. T. C. et al. Physical functioning and mortality: results from a cohort study of older adults in Hong Kong. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 23 (5), 858–864e5 (2022).

Hooker, K. et al. Depression among older adults in the united States by disaggregated race and ethnicity. Gerontologist 59 (5), 886–891 (2019).

Xiang, X. & An, R. Depression and onset of cardiovascular disease in the US middle-aged and older adults. Aging Ment Health. 19 (12), 1084–1092 (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wenlong Ding and Caoyang Fang wrote the main manuscript text and Fachaoo Shi prepared Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4; Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4;Cunming Fang prepared supplemmentary figure 1; Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that none of the authors have a conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The NHANES protocol has been approved by the NCHS Institutional Review Board, and this study does not contain any personally identifiable information. Therefore, the Ethics Committee of Xuancheng People’s Hospital has exempted this study from ethical approval requirements. Specifically, our study utilized a publicly available, de-identified dataset from NHANES, which has already obtained ethical approval from the NCHS. As our research involved secondary analysis of existing data without direct interaction with human subjects, the Ethics Committee of Xuancheng People’s Hospital granted an exemption from further ethical review.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, W., Shi, F., Fang, C. et al. Depression as a mediator between socioeconomic status and risk of All-Cause and cardiovascular mortality in diabetes and prediabetes. Sci Rep 15, 24581 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09258-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09258-7