Abstract

Food spoilage bacteria are responsible for food spoilage and often fabricate biofilms on various surfaces. Naturally, biofilms are constructed by multiple bacterial species. These biofilms are more difficult to control compared to single species biofilms. Effective multispecies biofilm treatments are necessary in the food industry. This research evaluated antibiofilm activities of Streptomyces sp. KP110 and Pseudomonas fluorescens JB 3B metabolites. Prior to this research, the two antibiofilm crude extracts had shown significant results against various single species biofilms, including Bacillus, Shewanella, Vibrio, etc. The crude extracts also showed quorum-quenching activities, further asserting the antibiofilm potential. This research further characterized these antibiofilm crude extracts against multispecies biofilms, as well as assessing the duration of biofilm formation inhibition. The food spoilage bacteria used in this study are Bacillus cereus, Bacillus subtilis, and Shewanella putrefaciens. Both crude extracts showed antibiofilm activities with better results against Gram-negative bacteria. The metabolites are also considered nontoxic, meaning they are potential candidates for industrial purposes. The dominant active compounds of Streptomyces sp. KP110 are ticlopidine and hexadecanoid acid, while Pseudomonas fluorescens JB 3B are phenol and indole.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Food spoilage is one major concern in food security and food safety. It leads economic losses for producers and poses health risks to consumers. Food spoilage bacteria play a huge role in food spoilage. In addition, they generally possess biofilm formation activity, leading to serious damage to both products and utensils used in the processes and negative health impact for food consumers. Biofilm are structured microbial communities embedded in an extracellular matrix that provides protection and enhances bacterial survival. Protected bacteria have superior defensive capabilities against various threats, such as antibiotics and immune systems. Bacteria can undergo genetic transfer inside biofilm, further enhancing their virulence level. Several food spoilage bacteria also produce toxins responsible for human illness1. Some toxins are thermostable and will persist in foods even after the cooking process2.

Many bacterial activities, including toxin production, food spoilage, and biofilm formation, rely on a communication process called quorum sensing. Quorum sensing is cell to cell communication related to the ability of microorganisms to detect cell density. Bacteria detect their surroundings by chemical communication. The chemical compound involved in quorum sensing is called autoinducer, which can vary across bacterial species. One approach to inhibit bacterial biofilm formation is to intervene in the quorum sensing mechanism3.

Biofilms are often composed of multiple bacterial species. These biofilms generally have higher endurance compared to single species biofilms. Each species in multispecies biofilms community has its own feature to cover the weakness of single species biofilm. Hence, effective treatment against single species biofilm is not guaranteed to work on multispecies biofilm4. This research evaluated antibiofilm activities of two antibiofilm crude extracts of bacteria which effectiveness had been proven against single species biofilms on previous studies, which were Streptomyces sp. KP1103 and phyllosphere bacteria Pseudomonas fluorescens JB 3B5. These crude extracts were applied to food spoilage bacteria Bacillus cereus ATCC 10,876, Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, and Shewanella putrefaciens ATCC 8071, which are relatively prevalent as food spoilage.

This research was aimed to determine the antibiofilm activities against single and multispecies biofilm and to identify the bioactive compounds related to the antibiofilm activity. Prior to this research, the two antibiofilm crude extracts had shown significant results against various single species biofilms, including Bacillus, Shewanella, Vibrio, etc. The crude extracts also showed quorum-quenching activities, further asserting the antibiofilm potential.

Results

Biofilm Inhibition

Within 7 days, each antibiofilm crude extract showed various inhibition values. This assay was performed to determine the antibiofilm activity over time. Crude extract of Streptomyces sp. KP110 reached its highest inhibition on the third day (Fig. 1a). On the other hand, the crude extract of P. fluorescens JB 3B reached its highest inhibition on the fifth day, except against B. subtilis which was optimum on the third day (Fig. 1b). Each experiment for different time spans was performed independently due to technical limitations, which may affect the variance of the result.

Biofilm destruction

The destruction assay was performed against multispecies biofilms to evaluate the antibiofilm activity against multispecies biofilms. Generally, both crude extracts had better performances against Gram-negative biofilms (Fig. 2). KP110 crude extract indicate better performance against single-species biofilms (p < 0.05), while JB 3B did not show significant differences between single and multi-species biofilm destruction.

Destruction activities of crude extracts from Streptomyces sp. KP110 and P. fluorescens JB 3B against various combinations of multispecies biofilms (n = 3, vertical bars are standard error, * signifies p value of less than 0.05 and ** as p value of less than 0.01 between treated and untreated samples, all effect sizes are > 2).

Metabolite toxicity assay

The brine shrimp lethality assay (BSLA) is performed to determine the toxicity levels of the two crude extracts based on their LC50 values (Table 1). The values were calculated from three independent samples.

Bioactive compound determination

GC-MS analysis found that the major compound of crude extract from Streptomyces sp. KP110 were ticlopidine and fatty acids, primarily hexadecanoic and octadecenoic acids (Supplementary Table S1), while the most abundant compounds found from LC-MS analysis were etomidate, cyclo(leucylprolyl), and maculosin (Supplementary Table S2). The LC-MS analysis performed on crude extract from P. fluorescens JB 3B found similar dominant compounds, which were etomidate, tryptophol, and maculosin (Supplementary Table S3).

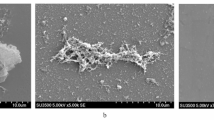

SEM and light microscopy analysis

Microscopy analyses were performed to confirm the numerical bioassay data. Visible biofilm structure degradation can be seen across all samples (Table 2). SEM analyses were performed on samples with more than 50% destruction activities and triple-species biofilms under P. fluorescens JB 3B treatment (48.7% destruction) (Fig. 3) while EDS analyses were shown on Table 3.

SEM analysis results of a untreated biofilm of B. cereus and S. putrefaciens, b B. cereus and S. putrefaciens biofilm under JB 3B treatment, c untreated biofilm of B. subtilis and S. putrefaciens, d B. subtilis and S. putrefaciens biofilm under KP110 treatment, e B. subtilis and S. putrefaciens biofilm under JB 3B treatment, f untreated biofilm of B. cereus, B. subtilis, and S. putrefaciens, and g B. cereus, B. subtilis, and S. putrefaciens biofilm under JB 3B treatment.

Discussions

Bacillus cereus and Bacillus subtilis are commonly found in foods with high protein and carbohydrate. It also produces thermostable toxins which endure cooking processes6. On the other hand, Shewanella putrefaciens mainly infects fish and can grow on low temperatures (psychrotolerant), meaning refrigeration does not completely stop Shewanella from growing. Infection of Shewanella poses various life-threatening diseases like cirrhosis and cancer7.

Despite having both physical and physiological differences, these three food spoilage bacteria share something in common with each other. They are able to construct biofilm for survival purposes in the environment. As motile bacteria, they will lose their motility during the initiation phase of biofilm formation. Extracellular substances like exopolysaccharides and proteins are then produced. These substances appear as slime-like substances in human eyes. The extracellular matrix serves as a resilient shelter for the bacteria and can stick to various surfaces, including foods. These food spoilage bacteria will produce various enzymes which affect food quality, with protease being the main enzyme to spoil protein-rich foods8,9.

Biofilm formation and several other activities like toxin production are regulated distinctly than other cellular activities. These activities are so called “cell-density dependent” because they are only active when sufficient cells are present in the vicinity. Bacterial cells communicate with each other via chemical molecules called autoinducer to assess the surrounding cell density. This cell-to-cell communication is called quorum sensing10.

Our research found that the two crude extracts were generally better for Gram-negative biofilm treatments. The destruction against biofilms of S. putrefaciens showed higher values (Fig. 2) compared to the other biofilms. However, both crude extracts could destroy Gram-positive biofilms as well. The numerical bioassay data were confirmed visually with microscopy (Table 2). Positive control images showed much higher violet area, which indicated the presence of biofilm. SEM figures also showed the destruction of biofilms (Fig. 3). Under the treatment of either crude extract, the cells were found to be more scattered, suggesting the destruction of biofilms.

EDS analysis revealed mineral changes due to antibiofilm treatment (Table 3). Treatment of double-species biofilms marked the drop of carbon and nitrogen, while pointing a noticeable rise of calcium. The depletion of carbon and nitrogen on the surface signifies the destruction of biofilms since they are made of primarily organic compounds. Calcium is an important mineral in supporting biofilm structures11. Destroying biofilms releases bound calcium trapped inside their structures. Since EDS only detects surface minerals, dispersed biofilms unveil more calcium to be detected. Treatment of triple-species biofilm leads to a different result. It rather showed 1.6-fold increase in carbon percentage and 3.7-fold increase in nitrogen percentage. The huge difference in nitrogen level might be related to protein synthesis. This phenomenon is suspected to be a special response of this triple-species biofilm community to the environmental stress imposed by P. fluorescens JB 3B crude extract.

Other than evaluating the destructive properties of the two crude extracts against multispecies biofilms, the determination of compound active period is also important. Our data showed that these crude extracts generally had the highest antibiofilm activity on the third day. However, they still held up to at least seven days of antibiofilm properties. This experiment was performed at approximately room temperature (28 °C) and the shelf-life will vary under different storage conditions.

The next consideration of antibiofilm application is the toxicity levels. BSLA was conducted to estimate the possible negative effects on the hosts. According to Wu12 a compound is considered toxic if the lethal concentration 50 (LC50) value is less than 1000 ppm. LC50 is the required concentration to eradicate 50% of the host population. Our data (Table 1) showed that the two crude extracts had LC50 values above 1000 ppm, meaning they are considered nontoxic. This further promises the safety for application in food industry.

Both biofilm inhibition and destruction can be administered using various mechanisms. Intervention in the quorum sensing mechanism (also called quorum quenching) may inhibit or destroy biofilms by interacting with the autoinducer molecules or quorum-sensing involved genes. Bacillus uses autoinducer-2 (AI-2, protein molecules) as their autoinducers10 while Shewanella uses C4 and C6 acyl homoserine lactone (AHL) molecules13,14. These autoinducer molecules can be degraded using protease and lactonase enzymes respectively. Other approaches of biofilm inhibition and destruction may involve inhibition of bacterial surface adhesion, alteration of bacterial physiology/metabolism, or biofilm degradation. Adhesion inhibition is usually done by changing the surface properties such as hydrophobicity, roughness, or texture. Alteration of bacterial metabolism can be achieved through various ions or compounds. Lastly, biofilm degradation is simply destroying the biofilm structure, either physically or chemically. Interfering bacterial metabolism tends towards biofilm inhibition rather than destruction. This includes interacting with the quorum sensing mechanism. Targeting other metabolisms like extracellular matrix production is also a feasible option. On the other hand, chemical biofilm degradation usually involves degrading-enzymes like proteases, amylases, or nucleases15.

Based on previous studies, several compounds found in the antibiofilm crude extracts had been proven to possess antibiofilm and/or antimicrobial properties. GC-MS analysis detected phenol, indole, ticlopidine, and fatty acids in our antibiofilm extracts. Phenol has been used extensively and widely known for its antimicrobial properties, and research by Walsh et al.16 also showed antibiofilm properties of phenol. Pseudomonas is known to produce phenol for the synthesis of their antimicrobial compounds17. Fatty acids in general also have antimicrobial/antibiofilm properties due to its chemical structure. Being an amphipathic molecule, fatty acid may act as surfactant and disrupt cell membrane and bacterial metabolism18.

Some of the compounds showed better antibiofilm activities against Gram-negative biofilms. One compound in P. fluorescens JB 3B crude extract, indole, is found to interfere with the quorum-sensing related gene expression in Gram-negative bacteria19. Gram-positive bacteria do have slight differences in their quorum sensing mechanism compared to Gram-negative bacteria, so indole might have lower potential against Gram-positive biofilm. Ticlopidine found in Streptomyces sp. KP110 crude extract also showed better performance against Gram-negative bacteria according to Pirhaghi et al.20. These findings align with our research data which showed better antibiofilm properties against Gram-negative biofilms.

Compounds found on LC-MS analysis still have limited studies. Etomidate is an anaesthetic agent for short surgical procedures21. Research conducted by Sá et al.22 found that etomidate has an antimicrobial activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). While the mechanism is still unknown, their research found cell death on MRSA under the treatment of etomidate, leading to the speculation that etomidate might induce apoptosis. Another research by Sá et al.23 showed antibiofilm properties of etomidate against fluconazole-resistant Candida spp. by binding to proteins involved in biofilm formation.

Cyclo(leucylprolyl) is another compound found from LC-MS analysis. Research by Li et al.24 tested the effect of cyclo(leucylprolyl) against the biofilm of Staphylococcus aureus. The result showed that the compound exerted antibiofilm activities by inhibiting exopolysaccharide (EPS) synthesis. Cyclo(leucylprolyl) was also found to inhibit the gene expression of adhesion and quorum sensing related genes, primarily by interfering with DNA transcription. Although there is currently no published study related to cyclo(leucylprolyl) against Bacillus or Shewanella, this compound is likely to have similar effects against species other than Staphylococcus aureus, since they all share the same principle in the quorum sensing mechanism.

Maculosin is an aromatic acid produced by both Streptomyces and Pseudomonas as their secondary metabolite. Research conducted by Paudel et al.25 and Shahid et al.26 had shown that maculosin possesses strong antimicrobial activity against vast microbial groups. Several species proven to be inhibited by maculosin are Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Candida albicans, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pyricularia oryzae, Aspergillus fumigatus, and Penicillium roquefortii. Besides, maculosin also has excellent antioxidant activity, which is to be expected from an aromatic compound. The antifungal activity of maculosin is found to be effective by inhibiting chitinase enzymes. Being a broad-spectrum antimicrobial agent, maculosin is expected to inhibit both Bacillus and Shewanella as well.

Tryptophol is a phenolic compound often found in fermented products like wine which induces sleep in humans. This compound offers positive health effects, particularly as antiatherogenic, anticancer, neuroprotective, antidiabetic, lipid-regulating, anti-obesity, and in promoting cardiovascular health27. Regarding biofilms, tryptophol is known to promote cell detachment to supress biofilm formation28. However, the test was only conducted on fungi. Currently, there is no study regarding tryptophol effect against bacterial biofilm.

Different compounds were detected between GC-MS and LC-MS analysis due to the difference in the approach. Overall, both analyses showed some compounds related to antimicrobe, anti-quorum sensing, and antibiofilm destruction.

This study has demonstrated the antibiofilm potential of the two crude extracts. However, further studies are required before they can be applied at an industrial scale. Currently, the bacteria were cultivated in an expensive medium, which is not suitable for industrial purposes. Further research should focus on developing a low-cost cultivation medium while preserving the antibiofilm activity. Moreover, the toxicity profile of these extracts requires more comprehensive evaluation, as BSLA alone is insufficient to classify them as food safe. In addition, bioinformatics analyses and further compound identification should be conducted. This may pave the way for the development of synthetic analogs with enhanced antibiofilm efficacy. Furthermore, these two crude extracts may also have practical applications in controlling utensil-related biofilm issues, where safety regulations are less stringent.

Methods

Bacterial cultivation

Streptomyces sp. KP110 was isolated from the marine environment Mutiara Beach, North Jakarta29 and Pseudomonas fluorescens JB 3B was isolated from leaf surface of Psidium guajava in Karanganyar, Jakarta30. Streptomyces sp. KP110 was grown in Yeast Malt Extract Agar (YMEA)3 and P. fluorescens JB 3B was grown in Brain Heart Infusion Agar (BHIA)1. Both were incubated at 28 °C for 48 h. Food spoilage bacteria B. cereus ATCC 10,876, B. subtilis ATCC 6633, and S. putrefaciens ATCC 8071 were grown in BHIA at 28 °C for 24 h.

Extraction of bioactive compounds

The bioactive compound extraction method refers to Vanessa and Waturangi1 and Mulya and Waturangi3. Streptomyces sp. KP110 was cultivated in Tryptone Soya Broth (TSB) supplemented with 1% (w/v) of glucose for seven days and P. fluorescens JB 3B was cultivated in BHIB for two days. Both strains were cultivated at 28 °C on a rotary shaker at 120 rpm. Bacterial cultures were then centrifuged at 7000×g for 30 min. Cell-free supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of ethyl acetate and incubated in a rotary shaker at 28 °C, 120 rpm, overnight. Ethyl acetate was evaporated in rotary evaporator and further dried in vacuum oven overnight. Extracted bioactive compounds were dissolved in 1% (v/v) of DMSO with final concentration of 20 mg mL− 1 and kept in −20 °C freezer.

Antibiofilm activity quantification

The quantification assay refers to Vanessa and Waturangi1. Food spoilage bacteria were inoculated to BHIB and incubated at 28 °C for 24 h. Each suspension was then diluted to OD600 = 0.132. For inhibition assay, 100 µL of each culture suspension was transferred to microplate and mixed with 100 µL antibiofilm crude extract. Each mixture was incubated at 28 °C for 1, 3, 5, and 7 days. For destruction assay, each suspension was equally mixed to create all possible combinations (Table 4). Then, 100 µL of each culture combination was transferred to microplate and incubated at 28 °C for 24 h before adding 100 µL of antibiofilm crude extract. For treatment control, we used 1% (v/v) of DMSO instead of antibiofilm crude extract. Biofilm quantification was performed using crystal violet dye.

After the incubation period, the liquid media inside the microplate was discarded. The microplate was rinsed twice with distilled water and air dried afterwards. Each well was added with 100 µL 0.4% (w/v) of crystal violet solution for 30 min. The excess dye was then discarded, and each well was rinsed five times with distilled water. After air drying, each well was added with 100 µL 96% (v/v) of ethanol. The absorbance was measured using microplate reader at 595 nm. This assay was performed with three replicates and antibiofilm activity was calculated using the following formula:

Metabolite toxicity determination

Metabolite toxicity was determined using the brine shrimp lethality assay (BSLA), referring to Raissa et al.31. Three mg of brine shrimp eggs were added to 250 mL artificial sea water consisting of 3.8% (w/v) of sodium chloride. The hatchery was illuminated with LED lights and aerated with an air pump. After 24 h, nauplii were collected and transferred into tubes. Each tube contained ten nauplii and was added with 4.5 mL of artificial sea water and 500 µL of antibiofilm crude extract. The concentration used was adjusted to 10, 100, 500, and 1000 ppm, diluted with artificial sea water. Positive control used K2Cr2O7, and negative control used 1% (v/v) of DMSO. The tubes were placed under LED lights for another 24 h, and death rate was calculated by the following formula:

Bioactive compound determination

The determination of bioactive compound was performed by Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis and Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis. GC–MS was performed at Atma Jaya University, Indonesia. The crude extract was dissolved in ethyl acetate and injected into the GC column. Helium gas was used as carrier gas with the flow rate of 24 mL min−1 and oven temperature of 325 °C. Compound names were interpreted based on the mass spectrum data of the peaks on GC chromatogram. LC–MS was performed at Institut Pertanian Bogor, Indonesia.

SEM and light microscopy analysis

The microscopy analysis and preparation procedures refer to Miller et al.32. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was performed at BRIN, Indonesia. Food spoilage bacteria were inoculated to BHIB and incubated at 28 °C for 24 h and diluted to OD600 = 0.132. Bacterial suspensions were mixed according to Table 4. Then, one mL of each suspension was grown in 1 × 1 cm2 cover glass and incubated at 28 °C for 24 h. After the incubation period, each cover glass was transferred to a new sterile petri dish with 500 µL crude extract and incubated for another 24 h. We used 1% (v/v) of DMSO for treatment control. For SEM preparation, each cover glass was added with 2.5% (v/v) of glutaraldehyde and incubated at 4 °C for 24 h. Then, the biofilms were dehydrated with 30%, 50%, 70%, 96%, and 100% (v/v) ethanol for 15 min and dried at 28 °C for 10 min. For light microscopy, each cover glass was rinsed with distilled water twice and stained with 0.4% (w/v) of crystal violet for 10 min. Each cover glass was rinsed once again with distilled water and was observed under the light microscope with 400× magnification.

Data analysis

Research data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25. The independent t test was used to analyze antibiofilm activity data, and simple linear regression was used to analyze BSLA data. Experiments were carried out with three replicates, and the statistical significance threshold was 0.05.

Conclusions

The two antibiofilm crude extracts emerged as potential candidates for food-spoilage related biofilm issues. Their potent antibiofilm activities and low toxicity, along with the possibility of combining the two crude extracts together, is expected to reduce food spoilage. Both Streptomyces sp. KP110 and P. fluorescens JB 3B crude extracts have also demonstrated significant destruction against multispecies biofilms which have been confirmed with microscopy determination. The antibiofilm activities are also able to inhibit biofilm for a certain duration. On top of their antibiofilm properties, several compounds like etomidate and maculosin also offer antimicrobial and potentially antioxidant properties. With further research, these crude extracts have the potential for further development as antibiofilm agents in food safety applications.

Data availability

All data deposited in the GenBank is publicly available with GenBank accession number PQ056889 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PQ056889) and MW680906 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/OM763955).

References

Vanessa, V. & Waturangi, D. E. Quantification of anti-quorum sensing and antibiofilm activity of phyllosphere bacteria against food spoilage bacteria. Nova Biotechnol. Chim. 20 (2), 1–8 (2021).

Regenthal, P., Hansen, J. S., André, I. & Lindkvist-Petersson, K. Thermal stability and structural changes in bacterial toxins responsible for food poisoning. PLoS One 12 (4) 1-15 (2017).

Mulya, E. & Waturangi, D. E. Screening and quantification of anti-quorum sensing and antibiofilm activity of Actinomycetes isolates against food spoilage biofilm-forming bacteria. BMC Microbiol. 21, 1 (2021).

Rendueles, O. & Ghigo, J. Multi-species biofilms: how to avoid unfriendly neighbors. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36, 972–989 (2011).

Rizkinata, D., Waturangi, D. E. & Yulandi, A. Synergistic action of bacteriophage and metabolites of Pseudomonas fluorescens JB3B and Streptomyces thermocarboxydus 18PM against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and Bacillus cereus and their biofilm. BMC Microbiol. 9, 24 (2024).

Lorenzo, J. M., Munekata, P. E., Dominguez, R., Pateiro, M. & Saraiva, J. A. Franco, D. Main groups of microorganisms of relevance for food safety and stability. Innov. Technol. Food Preserv. 53–107 (2018).

Yu, K., Huang, Z., Xiao, Y. & Wang, D. Shewanella infection in humans: epidemiology, clinical features and pathogenicity. Virulence 13 (1), 1515–1532 (2022).

Lemon, K. P., Earl, A. M., Vlamakis, H. C. & Aguilar, C. Kolter, R. Biofilm development with an emphasis on Bacillus subtilis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008 (322), 1–16 (2008).

Bagge, D., Hjelm, M., Johansen, C., Huber, I. & Gram, L. Shewanella putrefaciens adhesion and biofilm formation on food processing surfaces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67 (5), 2319–2325 (2001).

Lee, N., Kim, M. & Lim, M. Autoinducer-2 could affect biofilm formation by food-delivered Bacillus cereus. Indian J. Microbiol. 61 (1), 66–73 (2021).

Kobayashi, K. & Nishikawa, M. Calcium prevents biofilm dispersion in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 203 (14), e00114–e00121 (2021).

Wu, C. An important player in Brine shrimp lethality bioassay: the solvent. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 5 (1), 57–58 (2014).

Liu, L. et al. AHL-mediated quorum sensing to regulate bacterial substance and energy metabolism: a review. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 1–12 (1262) (2022).

Yu, H. et al. AHLs-produced bacteria in refrigerated shrimp enhanced the growth and spoilage ability of Shewanella baltica. J. Food Sci. Technol. 56 (1), 114–121 (2019).

Ghosh, A., Jayaraman, N. & Chatterji, D. Small-molecule Inhibition of bacterial biofilm. ACS Omega. 5 (7), 3108–3115 (2020).

Velusamy, P., Jeyanthi, V., Pachaiappan, R., Anbu, P. & Gopinath, S. C. B. Secretion of 2,4 di-tertbutylphenol by a new Pseudomonas strain SBMCH11: a tert-butyl substituted phenolic compound displayed antibacterial efficacy. Results Chem. 8, 101593 (2024)

Walsh, D. J., Livinghouse, T., Goeres, D. M., Mettler, M. & Steward, P. S. Antimicrobial activity of naturally occurring phenols and derivatives against biofilm and planktonic bacteria. Front. Chem. 7, 1-5 (663) (2019).

Ghareeb, M. A., Hamdi, S. A. H., Fol, M. F. & Ibrahin, A. M. Chemical characterization, antibacterial, antibiofilm, and antioxidant activities of the methanolic extract of Paratapes undulatus clams. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 12 (5), 219–228 (2022).

Sethupathy, S., Sathiya, E., Kim, Y., Lee, J. & Lee, J. Antibiofilm and antivirulence properties of Indoles against Serratia marcescens. Front. Microbiol. 11, 584812 (2020).

Pirhaghi, M. et al. The anti-platelet drug ticlopidine inhibits FapC fibrillation and biofilm production: highlighting its antibiotic activity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 1871 (2) (2023).

Valk, B. I. & Struys, M. M. R. F. Etomidate and its analogs: a review of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 60 (10), 1253–1269 (2021).

Sá, L. G. A. V. et al. Etomidate inhibits the growth of MRSA and exhibits synergism with Oxacillin. Future Microbiol. 15 (17), 1611–1619 (2020).

Sá, L. G. A. V. et al. Antifungal activity of etomidate against growing biofilms of fluconazole-resistant Candida spp. strains, binding to mannoproteins and molecular docking with the ALS3 protein. Med. Microbiol. 69 (10), 1221–1227 (2020).

Li, H., Li, C., Ye, Y., Cui, H. & Lin, L. Inhibition mechanism of cyclo (L-Phe-L-Pro) on early stage Staphylococcus aureus biofilm and its application on food contact surface. Food Biosci. (49) (2022).

Paudel, B. et al. Maculosin, a non-toxic antioxidant compound isolated from Streptomyces sp. KTM18. Pharm. Biol. 59 (1), 931–934 (2021).

Shahid, I. et al. Profiling of antimicrobial metabolites of plant growth promoting Pseudomonas spp. Isolated from different plant hosts. 3 Biotech. 11 (2), 48 (2021).

Marques, C., Dinis, L. T., Santos, M. J., Mota, J. & Vilela, A. Beyond the bottle: exploring health-promoting compounds in wine and wine-related products—extraction, detection, quantification, aroma properties, and terroir effects. Foods 1 (23), 4277 (2023).

Khan, M. F., Saleem, D. & Murphy, C. D. Regulation of Cunninghamella spp. biofilm growth by tryptophol and tyrosol. Biofilm 3, 100046 (2021).

Vidyawan, V. Screening of Actinomycetes from various environment sediments to inhibit biofilm formation of Vibrio cholerae [thesis]. In Jakarta (ID): Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya (2012).

Juliana Screening of phyllosphere and endophytic microbes producing antibacterial or anti quorum sensing activity from Ageratum conyzoides, Coleus amboinicus, and Psidium guajava [skripsi/ undergraduate thesis] In Jakarta (ID): Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya (2011).

Raissa, G., Waturangi, D. E. & Wahjuningrum, D. Screening of antibiofilm and anti-quorum sensing activity of Actinomycetes isolates extracts againts aquaculture pathogenic bacteria. BMC Microbiol. 20, 343 (2020).

Miller, T. & Waturangi, D. E. Yogiara. Antibiofilm properties of bioactive compounds from Actinomycetes against foodborne and fish pathogens. Sci. Rep. 18614 (12) (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thankfully acknowledge the funding support of Indonesian Ministry of Education and Culture through competitive National Research Grant 2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.H.Conducted the research and data analysis, prepared proposal writing and manuscript under advisory of DEW and AY. A.Y. Data analysis. D.E.W. Research design, data analysis and Person In charge of all the research projectAll authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable for this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Halim, B., Waturangi, D.E. & Yulandi, A. Control of biofilm from single and multispecies bacteria associated with food spoilage using metabolite of Streptomyces sp. KP110 and Pseudomonas fluorescens JB 3B. Sci Rep 15, 23956 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09259-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09259-6