Abstract

While post-infectious (PI-ME/CFS) and gradual onset (GO-ME/CFS) myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) manifest similar symptoms, it has long been suspected that different disease processes underlie them. However, the lack of biological evidence has left this question unanswered. In this study, how white matter microstructural changes in PI-ME/CFS and GO-ME/CFS patients were investigated. PI-ME/CFS and GO-ME/CFS patients were recruited based on consensus diagnoses made by two experienced clinicians and compared their diffusion MRI features with those of rigorously matched healthy controls (HCs) with sedentary lifestyles. PI-ME/CFS participants showed significantly higher axial diffusivity (AD) in several association and projection fibres compared to HCs. Higher AD in PI-ME/CFS was significantly related to worse physical health. In contrast, GO-ME/CFS participants exhibited significantly decreased AD in the corpus callosum. Lower AD in GO-ME/CFS was significantly associated with worse mental health in commissural and projection fibres. No significant group differences were found for fractional anisotropy, mean diffusivity, or radial diffusivity. Distinct patterns of AD alterations in PI-ME/CFS and GO-ME/CFS provide neurophysiological evidence of different disease processes and highlight the heterogeneities of ME/CFS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) is a complex, debilitating disorder characterised by persistent fatigue, cognitive impairment, and various other symptoms that can have a significant impact on patients’ quality of life1. Despite its significant burden, the underlying pathophysiological mechanism of ME/CFS remains unclear, impeding the development of accurate diagnostic methods and effective treatments.

White matter (WM) connects different brain regions, enabling signal transmission and coordination of brain functions. Impairments in WM may contribute to symptoms of ME/CFS, such as profound fatigue, cognitive impairments (“brain fog”), and dysregulated autonomic function. Over the past few years, some studies have investigated WM abnormalities in ME/CFS patients using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and investigated the potential neurological foundations of the disorder. Zeineh et al.2 observed increased fractional anisotropy (FA) and axial diffusivity (AD), and decreased radial diffusivity (RD) in the right arcuate fasciculus in ME/CFS patients who met Fukuda criteria. Further, changes in FA were related to the disease severity. Kimura et al.3 observed a significant decrease in FA and unchanged mean diffusivity (MD) in the genu of the corpus callosum and the anterior limb of the right internal capsule in ME/CFS patients who met all the Fukuda criteria, the Canadian Consensus Criteria (CCC), and the International Consensus Criteria (ICC). Thapaliya et al.4 did not find any significant group differences in DTI metrics between the ME/CFS patients who met Fukuda criteria and healthy controls (HCs). For patients who met ICC Criteria, they found significantly decreased AD and MD in the midbrain and pons, and increased RD in the medulla compared with HCs. In addition, Kimura et al.5 found a significant negative correlation between MD and the serum levels of several autoantibody titres against adrenergic/muscarinic receptors, mainly in the right frontal operculum for ME/CFS patients who met all the Fukuda criteria, the CCC Criteria, and the ICC Criteria. They also observed a significant negative correlation between FA and the disease duration in the right frontal operculum. Furthermore, Josev et al.6 did not find significant group differences in DTI metrics between the pediatric ME/CFS patients who met CCC Criteria and HCs. In summary, prior DTI studies on ME/CFS have identified WM abnormalities, yet they have yielded inconsistent findings. These discrepancies lead us to postulate that ME/CFS is a heterogeneous illness with distinct white matter impairments.

Two onset types were observed in the development of ME/CFS clinically1,7: post-infectious (PI-ME/CFS) or gradual onset (GO-ME/CFS). In PI-ME/CFS, ME/CFS symptoms develop rapidly following a viral or bacterial infection, where the infection can include Epstein-Barr, Ross River, Coxiella burnetti, Q fever, influenza, and other coronaviruses, and most ME/CFS symptoms manifest after an infectious episode (64–80%). In contrast, GO-ME/CFS is characterised by a slow, progressive development of symptoms over months or even years without a clear infectious trigger. Despite the distinct disease progression pathways, few studies have explored the biological differences between PI- and GO-ME/CFS. Investigating white matter differences across these groups may clarify whether PI-ME/CFS and GO-ME/CFS share a common neurobiological basis or represent pathophysiologically distinct syndromes.

We hypothesised that PI- and GO-ME/CFS are associated with distinct WM impairments. Diffusion MRI offers a non-invasive method to explore these questions by quantifying microstructural properties of white matter tracts. By comparing DTI metrics between ME/CFS subtypes and healthy controls, and assessing their associations with clinical measures, we aim to identify potential imaging biomarkers and enhance our understanding of ME/CFS pathophysiology.

Methods

The study was approved by University of the Sunshine Coast Ethics Committee (A191288) and registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12622001095752). Participants provided written informed consent prior to participating in the study. All datasets were de-identified before processing. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Participants were recruited by social media advertisement. All participants (including controls) underwent an MRI scan as part of their participation in the study. The MRI scans were conducted specifically for this study. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the participants are detailed in the recently published protocol paper8. Adult participants (18–65 years old) were recruited, and the critical exclusion criteria include individuals (i) outside the age range, (ii) with a body mass index (BMI) > 35, (iii) smoking (including marijuana or substance usage). Additional exclusion criteria for HCs include individuals with mental disorders. ME/CFS patients were independently interviewed by two clinicians to confirm a CCC-consistent9 diagnosis of ME/CFS. A consensus diagnosis approach was employed to minimise the risk of an ill-defined disease cohort. Patients were then classified into two groups based on the onset of their illness to lead to a more homogeneous patient group. Summary scores of clinical measures (see following) were provided to the clinicians to assist with diagnosis during their interviews. Additionally, this study intentionally recruited HCs with sedentary lifestyles (< 60 min in moderate or high-intensity activity (i.e., exercise) per week) to reduce the confounding effects of disease deconditioning10. Activity levels for all participants were monitored by the Actigraph GT3X-BT device (ActiGraph LLC., United States) for 14 days, seven days before and after MRI scans. All participants were free of centrally acting medications for at least two weeks and supplements for at least one week before MRI scan.

This study investigated WM DTI characteristics in ME/CFS patients with a rigorous approach, employing (i) an appropriate sample size with a 1:1 ratio of patients to HCs (N = 86 in the PI-ME/CFS group, and N = 66 in the GO-ME/CFS group). Although unequal group size can be corrected by statistical modifications, equal group size increases power in the analysis, allowing for a better chance of detecting true differences between groups11. Equal group size also reduces biases caused by differences in experimental units among groups, leading to more accurate and reliable results12. (ii) The metadata and symptom scores were provided on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12791948).

Clinical measures

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), 36-item Short-Form (SF-36) Health Survey, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and Bell’s Disability Scale (BDS) questionnaires were completed by all participants8. The HADS-depression score, HADS-anxiety score, SF-36 mental component summary (MCS), SF-36 physical component summary (PCS), global PSQI score, and BDS score were extracted according to the corresponding instrumental guidelines. In addition, the disease severity and disease duration of ME/CFS patients were evaluated by two clinicians. Furthermore, the metabolic equivalents (MET) rate of the task from the Actigraph data was calculated using the Freedson Adult (1998) algorithm13 by ActiLife® software to measure the activity level for each participant.

Some behavioural measures of MET, depression, and anxiety scores were missing during data collection. An imputation approach based on age-specific groups14 was adopted to address these gaps. Participants were grouped into 10-year age bands (18–27, 28–37, …, 58–65 years). Age was chosen as the stratifying variable because it is a key determinant of the behavioural measures in this cohort. The 10-year bandwidth provides sufficient group sizes for stable estimates while capturing meaningful life-stage differences, and the imputation within diagnostic subgroups (controls vs. ME/CFS patients) maintains disease-status specific patterns. For seven of the MET control variables, the missing values were imputed using the mean of the corresponding 10-year age-specific control group. Similarly, for the MET of one PI-ME/CFS and three GO-ME/CFS patients, the missing values were imputed by taking the mean of the corresponding 10-year age-specific ME/CFS patient group. Additionally, the missing values for the depression and anxiety scores of one control participant were imputed using the mean of the corresponding 10-year age-specific control group. This approach of systematically using 10-year age-specific group means to impute the missing values helped maintain the integrity of the dataset and preserved the relationships between these variables and others included in the analysis.

MRI acquisition

Brain images were acquired using a 3 T Skyra MRI scanner (Germany, Erlangen) with a 64-channel head coil.

The structural MRI data were collected using a T1-weighted magnetisation prepared rapid gradient-echo sequence (MPRAGE): 208 slices, dimension 256 × 256, voxel size 1 mm × 1 mm × 1 mm, TR/TE = 2,200/1.71ms, flip angle 7°.

The DTI were acquired using a multiband EPI sequence (72 slices, multiband factor 3, dimension = 114 × 114, voxel size 2 × 2 × 2 mm3 TR/TE = 4,500/123ms; free diffusion mode, bipolar diffusion scheme with two diffusion weighting of b = 1000 and b = 2,500 s/mm2 with noncolinear diffusion directions 27 and 62, respectively, and eight volumes of b = 0 s/mm2, and phase encoding direction = anterior to posterior). Six volumes of b = 0 s/mm2 with opposite phase encoding direction in posterior to anterior are also collected for the eddy current correction.

Imaging processing

The DTI data were analysed using the established tool, tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS)15, in the Functional MRI of the Brain (FMRIB) Software Library v6.0 (FSL). TBSS is a whole-brain approach that allows for the analysis of diffusion characteristics across the entire brain.

The standard FSL FDT (FMRIB’s Diffusion Toolbox)16 pipeline was used to preprocess the diffusion data. The effects of motion for the six volumes of b = 0 s/mm2 with opposite phase-encoding direction EPI images were reduced using ‘mcflirt’. The warping field required for EPI distortion correction was calculated using ‘TOPUP’. The brain mask was generated using ‘bet2’ with threshold 0.2 on the b = 0 s/mm2 images which is an output from ‘TOPUP’ command above. The eddy current induced distortion correction and motion correction were corrected using ‘eddy_openmp’, and eddy quality control (qc) tool was used to perform the quality control both at the single subject and group level. Diffusion metrics of FA, MD, AD, and RD, were created by fitting a diffusion tensor model at each voxel by using ‘dtifit’. Each participant’s FA image was nonlinear registered into Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 152 standard space using TBSS. The FSL_HCP1065 FA 1 × 1 × 1 mm standard-space image was used as the target. The same nonlinear deformations were also applied to other non-FA images (MD, AD, and RD).

Statistical analysis

The Wilcoxon rank sum test17 was used to compare the demographic data and behavioural scores between groups. The unpaired 2-sample t-test was implemented using the ‘randomise’ tool18 in FSL to compare the differences in each diffusion metric between the HCs and patient groups. Sex, age, BMI, MET, depression, and anxiety scores were included as nuisance covariates in TBSS analysis. This comparison used a nonparametric permutation inference method with 10,000 permutations at each voxel19. Family-wise error (FWE) with threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) corrected p-value < 0.05 was used to indicate significant differences. All reported p-values in the main document were derived from t-tests (including general linear modelling for β) or their non-parametric equivalents, except for comparisons of the categorical variable (sex), which were evaluated using the χ² test. To ensure the observed group differences in diffusion metric are not influenced by potential artefacts from registration or distortion during normalisation to MNI space, the regions with significant group differences were mapped back to the participants’ native MR space using the inverse transformation by ‘applywarp’.

To further explore the relationship between microstructural changes and clinical symptoms, multiple regression analyses were performed using the ‘randomise’ tool. Multiple regressions between DTI metrics with four clinical scores, MCS, PCS, global PSQI, and BDS scores, were performed for all participants. The same multiple regression analyses were also conducted on each patient group. Additionally, the associations between DTI metrics and measures of disease severity and disease duration were examined in the patient group only. Note that one GO-ME/CFS participant did not have MCS and PCS scores and therefore was excluded from multiple regression analyses for MCS and PCS. In addition, one GO-ME/CFS and two PI-ME/CFS participants did not have global PSQI scores and were therefore excluded from multiple regression analyses for PSQI. All multiple regressions also included sex, age, BMI, MET, depression, and anxiety scores as nuisance covariates. FWE corrected p < 0.05 with TFCE was used to reflect significant regression.

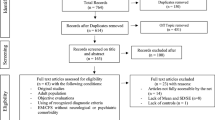

In this study, the diffusion MRI results were compared between PI-ME/CFS (n = 43) and matched HCs (n = 43) in the PI-ME/CFS group (Fig. 1), and between GO-ME/CFS (n = 33) and matched HCs (n = 33) in the GO-ME/CFS group. However, the HCs groups in these two comparisons included overlapping participants, introducing potential pseudo-replication and raising the possibility that the observed differences might be influenced by the composition with different healthy control groups. To address this concern, a supplementary three-group analysis between all eligible participants for PI-ME/CFS (n = 43), GO-ME/CFS (n = 33), and HCs (n = 58) after age, sex and MET matching and before number matching (1:1) was conducted. The results are presented in Appendix B in the supplementary information to ensure that the observed differences between groups are not attributed to the healthy control group and provide additional confirmation of the main findings.

Results

Participant characteristics

DTI data from 143 participants were analysed, including 76 participants with ME/CFS (mean age, 42.64 ± 12.71 [SD, standard deviation]; 64 women) and 67 HCs (mean age, 37.51 ± 11.57 [SD]; 52 women). The PI-ME/CFS group consisted of 43 PI-ME/CFS participants (mean age, 42.58 ± 12.41 [SD]; 37 women) and 43 HCs (mean age, 40.19 ± 8.29 [SD]; 37 women) (Fig. 1). The GO-ME/CFS group consisted of 33 GO-ME/CFS participants (mean age, 42.03 ± 12.87 [SD]; 26 women) and 33 HCs (mean age, 42.18 ± 7.35 [SD]; 26 women).

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics and behavioural assessments for the study participants in the final analysis for PI-ME/CFS group. There are no significant differences in age (p = 0.67), BMI (p = 0.82), MET rate (p = 0.10), or MRI scan time (p = 0.55) between the PI-ME/CFS patients and HCs. Compared to PI-ME/CFS, the HCs showed reduced HADS anxiety (p < 0.001) and depression (p < 0.001). The HCs also have increased SF-36 mental health (p < 0.001) and physical health (p < 0.001). In addition, the HCs have better overall sleep quality (p < 0.001) and lower level of disability (p < 0.001) than the patient’s group.

Table 2 demonstrates the demographic characteristics and behavioural assessments for the study participants in the final analysis for GO-ME/CFS group. There are no significant differences in age (p = 0.75), BMI (p = 0.27), MET rate (p = 0.09), and MRI scan time (p = 0.57) between the GO-ME/CFS patients and HCs. Compared to GO-ME/CFS, the HCs showed reduced HADS anxiety (p < 0.001) and depression (p < 0.001). The HCs also have increased SF-36 mental health (p < 0.001) and physical health (p < 0.001). In addition, the HCs have better overall sleep quality (p < 0.001) and lower level of disability (p < 0.001) than the patient’s group.

Supplementary Table S7 (Appendix B.1) shows that PI-ME/CFS and GO-ME/CFS patients are effectively equivalent in terms of demographic characteristics and behavioural assessments, with no significant differences observed in sex, age, BMI, MET rate, or any clinical scores.

Table 3 highlights the key differences between this study and three previous studies (2–4) that found alterations in DTI metrics in ME/CFS.

Higher AD in PI-ME/CFS participants than HCs

Figure 2 illustrates the TBSS AD results between the HCs and PI-ME/CFS patient groups in MNI 152 standard space. As shown in Fig. 2, the ADs in the PI-ME/CFS patient group were significantly higher than those in the HCs in the following fibre tracts: association fibres (right superior longitudinal fasciculus, right uncinate fasciculus, and right external capsule), and projection fibres (left inferior cerebellar peduncle, middle cerebellar peduncle, left superior cerebellar peduncle, right superior corona radiata, right posterior corona radiata, right sagittal stratum, corticospinal tract, and left medial lemniscus). There were no significant group differences in TBSS for FA, MD, and RD in the PI-ME/CFS group. To further validate the observed group differences in AD, the significant group difference regions were mapped back to the participants’ native MR space. The results (Supplementary Fig. S3 and Supplementary Table S1, Appendix A.2) confirm that these differences persist in native space, validating the robustness of the findings. In addition, the significantly higher ADs in PI-ME/CFS participants than HCs were also found in the three-group analysis (Supplementary Fig. S10, Appendix B.2). This further supports the robustness and reliability of the findings.

The tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) results of axial diffusivity (AD) between the healthy control and post-infectious ME/CFS (PI-ME/CFS) participant groups. Results are displayed in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 152 standard space based on the reference FSL_HCP1065 fractional anisotropy 1 × 1 × 1 mm standard-space image. The top row shows the results from six different axial slices, where the z-coordinates in MNI space from left to right are z = −12 mm, −2 mm, 8 mm, 18 mm, 28 mm, and 38 mm, respectively. The middle row shows the results from six different coronal slices, where the y-coordinates in MNI space from left to right are y = −46 mm, −36 mm, −26 mm, −16 mm, −6 mm, and 4 mm, respectively. The bottom row shows the results from six different sagittal slices, where the x-coordinates in MNI space from left to right are x = −35 mm, −20 mm, −5 mm, 10 mm, 25 mm, and 40 mm, respectively. Red-yellow clusters show the significant increased AD in PI-ME/CFS participants. The colour bar represents 1-p values, with higher values indicating greater levels of statistical significance.

Higher AD in PI-ME/CFS correlated with worse physical health

Among all participants in the PI-ME/CFS group, which included both patients and HCs, significantly negative correlations were observed between AD and PCS in the following fibre tracts (Fig. 3): association fibres (right superior longitudinal fasciculus, right superior fronto-occipital fasciculus, and right external capsule), and projection fibres (right posterior thalamic radiation, right superior corona radiata, right anterior corona radiata, right posterior corona radiata, right posterior limb of internal capsule, right retrolenticular part of internal capsule, and right anterior limb of internal capsule). There were no other significant correlations between AD and the three clinical scores, MCS, PSQI, and BDS scores, for all participants in the PI-ME/CFS group. Similarly, the significant correlation regions as shown in Fig. 3, which overlapped with those found in group difference in AD between HCs and PI-ME/CFS, were mapped back to the participants’ native MR space. The results (Supplementary Table S2, Appendix A.2) confirm that the significant negative correlations observed in MNI space are consistent with those in native space, supporting the validity of the findings. Furthermore, the significant negative correlations were also confirmed in the three-group analysis (Supplementary Fig. S11, Appendix B.3). This consistency further supports the robustness of the findings.

The multiple regression results of axial diffusivity (AD) with physical component summary (PCS) among all participants in the post-infectious ME/CFS (PI-ME/CFS) group. Results are displayed in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 152 standard space based on the reference FSL_HCP1065 fractional anisotropy 1 × 1 × 1 mm standard-space image. The top row shows the results from six different axial slices, where the z-coordinates in MNI space from left to right are z = −12 mm, −2 mm, 8 mm, 18 mm, 28 mm, and 38 mm, respectively. The middle row shows the results from six different coronal slices, where the y-coordinates in MNI space from left to right are y = −46 mm, −36 mm, −26 mm, −16 mm, −6 mm, and 4 mm, respectively. The bottom row shows the results from six different sagittal slices, where the x-coordinates in MNI space from left to right are x = −35 mm, −20 mm, −5 mm, 10 mm, 25 mm, and 40 mm, respectively. Blue-green clusters show the significant negative correlation of AD with PCS for all participants in the PI-ME/CFS group. The colour bar represents 1-p values, with higher values indicating greater levels of statistical significance.

Higher AD in PI-ME/CFS correlated with short disease duration

For the multiple regressions exclusively conducted on the PI-ME/CFS patient group, significantly negative correlation was observed between AD and disease duration in an association fibre (right external capsule) (Fig. 4).

The multiple regression results of axial diffusivity (AD) with disease duration for post-infectious ME/CFS (PI-ME/CFS) patient group. Results are displayed in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 152 standard space based on the reference FSL_HCP1065 fractional anisotropy 1 × 1 × 1 mm standard-space image. The top row shows the results from six different axial slices, where the z-coordinates in MNI space from left to right are z = −12 mm, −2 mm, 8 mm, 18 mm, 28 mm, and 38 mm, respectively. The middle row shows the results from six different coronal slices, where the y-coordinates in MNI space from left to right are y = −46 mm, −36 mm, −26 mm, −16 mm, −6 mm, and 4 mm, respectively. The bottom row shows the results from six different sagittal slices, where the x-coordinates in MNI space from left to right are x = −35 mm, −20 mm, −5 mm, 10 mm, 25 mm, and 40 mm, respectively. Blue-green clusters show the significant negative correlation of AD with disease duration for PI-ME/CFS patient group. The colour bar represents 1-p values, with higher values indicating greater levels of statistical significance.

For the multiple regressions exclusively conducted on the PI-ME/CFS patient group, there were no other significant correlations between AD and the five clinical scores: MCS, PCS, global PSQI, BDS, and disease severity scores.

Given the lack of differences between PI-ME/CFS participants and HCs in FA, MD and RD, the multiple regression analyses between those measures and the clinical measures in the PI-ME/CFS group were provided in appendix A.1 in the supplementary information for completeness.

Lower AD in GO-ME/CFS participants than HCs

Figure 5 illustrates the TBSS AD results between the HCs and GO-ME/CFS patient groups in MNI 152 standard space. As shown in Fig. 5, the ADs in the GO-ME/CFS patient group were significantly lower than those in the HCs in the commissural fibres [body and genu of corpus callosum (CC)]. There were no significant group differences in TBSS for FA, MD, and RD in the GO-ME/CFS group. The observed group differences in AD persist in native space (Supplementary Fig. S8 and Supplementary Table S3, Appendix A.4), ensuring that the findings are not influenced by potential artefacts from normalisation to MNI space. In addition, the significantly lower ADs in GO-ME/CFS participants than HCs were also found in the three-group analysis (Supplementary Fig. S13, Appendix B.4). These results confirm the validity of the observed differences.

The tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) results of axial diffusivity (AD) between the healthy control and gradual onset ME/CFS (GO-ME/CFS) participant groups. Results are displayed in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 152 standard space based on the reference FSL_HCP1065 fractional anisotropy 1 × 1 × 1 mm standard-space image. The top row shows the results from six different axial slices, where the z-coordinates in MNI space from left to right are z = −12 mm, −2 mm, 8 mm, 18 mm, 28 mm, and 38 mm, respectively. The middle row shows the results from six different coronal slices, where the y-coordinates in MNI space from left to right are y = −46 mm, −36 mm, −26 mm, −16 mm, −6 mm, and 4 mm, respectively. The bottom row shows the results from six different sagittal slices, where the x-coordinates in MNI space from left to right are x = −35 mm, −20 mm, −5 mm, 10 mm, 25 mm, and 40 mm, respectively. Blue-green clusters show the significant decreased AD in GO-ME/CFS participants. The colour bar represents 1-p values, with higher values indicating greater levels of statistical significance.

Lower AD in GO-ME/CFS correlated with worse mental health

Among all participants in the GO-ME/CFS group (including patients and HCs), significantly positive correlations were observed between AD and MCS in the following fibre tracts (Fig. 6): commissural fibres (body and genu of CC), and projection fibres (superior corona radiata, and anterior corona radiata). The significant positive correlations remain in native space (Supplementary Table S4, Appendix A.4) for regions which overlapped with those found in group difference in AD between HCs and GO-ME/CFS, further supporting the reliability of the findings. Furthermore, the significant positive correlations were consistent with the findings from the three-group analysis (Supplementary Fig. S17, Appendix B.5). This agreement further supports the reliability of the correlations identified. There were no other significant correlations between AD and the three clinical scores, PCS, global PSQI, and BDS scores, for all participants in the GO-ME/CFS group.

The multiple regression results of axial diffusivity (AD) with mental component summary (MCS) among all participants in the gradual onset ME/CFS (GO-ME/CFS) group. Results are displayed in Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 152 standard space based on the reference FSL_HCP1065 fractional anisotropy 1 × 1 × 1 mm standard-space image. The top row shows the results from six different axial slices, where the z-coordinates in MNI space from left to right are z = −12 mm, −2 mm, 8 mm, 18 mm, 28 mm, and 38 mm, respectively. The middle row shows the results from six different coronal slices, where the y-coordinates in MNI space from left to right are y = −46 mm, −36 mm, −26 mm, −16 mm, −6 mm, and 4 mm, respectively. The bottom row shows the results from six different sagittal slices, where the x-coordinates in MNI space from left to right are x = −35 mm, −20 mm, −5 mm, 10 mm, 25 mm, and 40 mm, respectively. Red-yellow clusters show the significant positive correlation of AD with MCS for all participants in the GO-ME/CFS group. The colour bar represents 1-p values, with higher values indicating greater levels of statistical significance.

For the multiple regressions exclusively conducted on the GO-ME/CFS patient group, there were no other significant correlations between AD and the six clinical scores: MCS, PCS, global PSQI, BDS, disease severity, and disease duration scores.

Given the lack of differences between GO-ME/CFS participants and HCs in FA, MD and RD, the multiple regression analyses between those measures and the clinical measures in the GO-ME/CFS group were provided in appendix A.3 in the supplementary information for completeness.

Discussion

This study investigated WM abnormalities in post-infectious (PI-ME/CFS) and gradual-onset ME/CFS (GO-ME/CFS) participants. The key findings were WM abnormalities in opposite directions: significantly increased AD among PI-ME/CFS participants compared to HCs and significantly decreased AD among GO-ME/CFS participants compared to controls. The increased AD in PI-ME/CFS were correlated with worse physical health, while decreased AD in GO-ME/CFS were related to worse mental health.

This study revealed a significant increase in AD in PI-ME/CFS patients compared to the control group in multiple white matter tracts, including association and projection fibres. The affected regions, such as the right superior longitudinal fasciculus, right uncinate fasciculus, and various cerebellar peduncles, are involved in emotional processing20, and motor control21. These findings align with the diverse symptomatology of ME/CFS, including motor disturbances22. Several studies have also reported the exclusively increased AD in other neurological conditions associated with axonal damage, such as COVID-1923, mild traumatic brain injury (TBI)24, or retired professional football players with multiple concussions25. Elevated AD has been linked to axonal injury or loss of structural integrity within white matter pathways24,25, and these findings suggest possible alterations in the integrity or arrangement of axons within specific white matter tracts as shown in Fig. 2. Increased AD has also been associated with underlying neuroinflammatory processes within the central nervous system26. The increased AD observed in PI-ME/CFS patients may reflect a state of axonal swelling or disrupted axonal transport, possibly resulting from immune activation or neuroinflammation following infection. The postulation of inflammation-related swelling was supported by the negative correlations between the disease durations and AD values, suggesting that inflammation settles over time. Recent studies on herpes simplex virus encephalitis27, and COVID-1928 have likewise reported improvements in WM microstructure during patient recovery. Moreover, Hornig et al.29 found that ME/CFS cases with a shorter disease duration exhibited pronounced activation of both pro and antiinflammatory cytokines. This interpretation aligns with previous studies suggesting that post-infectious ME/CFS may involve prolonged immune dysregulation, including elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines and microglial activation29,30,31. Inflammation can cause cytotoxic edema, demyelination, and axonal damage, which in turn disrupts the organisation of axonal fibres and increases the diffusion of water along the principal axis of the fibres26. Neuroinflammation has been observed in patients with ME/CFS5, COVID-1932, and TBI33. Retired professional football players with a history of multiple concussions are at an increased risk of developing long-term neurological issues, such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE)34, where CTE is associated with neuroinflammation. Therefore, increased AD may serve as a potential biomarker of neuroinflammation in the PI-ME/CFS cohort, providing valuable insights into the underlying pathophysiology of these disorders.

In contrast, the GO-ME/CFS patients exhibited a significant decrease in AD compared to HCs in the body and genu of the corpus callosum, which are crucial for interhemispheric communication. This finding suggests that ME/CFS patients with a gradual onset may have different underlying pathophysiological mechanisms compared to those with post-infectious onset. The reduced AD in these commissural fibres could potentially contribute to cognitive4 and information processing35 deficits often reported in ME/CFS patients. The commissural fibres of the corpus callosum primarily enable communication and integration between the brain’s hemispheres, while the projection fibres of the corona radiata are essential for transmitting information between cortical and subcortical regions, contributing significantly to motor control, sensory processing, and various cognitive functions36. Decreased AD has been linked to axonal degeneration or loss within white matter pathways in other neurological conditions associated with axonal degeneration, such as major depressive disorder37, schizophrenia38, bipolar disorder39, obsessive-compulsive disorder40, and multiple sclerosis41. Unlike the immune-triggered pathology hypothesised in PI-ME/CFS, gradual onset cases may involve long-term dysregulation of the central nervous system, including mitochondrial dysfunction, impaired cerebral perfusion, or altered autonomic regulation mechanisms that have been proposed in previous ME/CFS research42,43. These chronic mechanisms may result in reduced axonal density or integrity, thereby manifesting as decreased AD in GO-ME/CFS patients. Increased oxidative stress and impaired antioxidant defences have been reported in ME/CFS44, major depressive disorder45, schizophrenia46, bipolar disorder47, obsessive-compulsive disorder48, and multiple sclerosis49. The oxidative stress can result in cellular damage and impaired function in multiple organ systems, including the brain50. Mitochondrial abnormalities have also been observed in ME/CFS44, major depressive disorder51, schizophrenia52, bipolar disorder53, obsessive-compulsive disorder54, and multiple sclerosis55, which contribute to fatigue, cognitive impairment, and other symptoms.

No significant differences in FA, MD, or RD were observed between PI-ME/CFS patients, GO-ME/CFS patients, and controls, in contrast to previous studies that reported changes in these diffusion metrics in ME/CFS2,3,4. However, the inconsistencies in findings across studies may arise from variations in sample characteristics, patient criteria, or statistical methodologies. This study collected additional opposite phase encoding data, which can improve the correction of eddy current distortions and potentially lead to more accurate DTI results56. Furthermore, the statistical analysis conducted in this study using a rigorous statistical methodology (FWE corrected p < 0.05 with TFCE), where FWE correction is less likely to produce false positive results but may be less sensitive in detecting true effects than FDR correction25, and the TFCE approach can provide better sensitivity than cluster-based thresholding57.

When the correlation between AD and clinical symptoms was explored in the PI-ME/CFS group, a significant negative association between AD and physical health score was found in various white matter tracts, including association and projection fibres across all participants. This negative relationship implies that higher AD is associated with poorer physical health outcomes. This finding could reflect the impact of PI-ME/CFS on physical functioning, where increased AD may serve as a potential biomarker for disease severity in physical domains. Motor disturbances are a significant and often debilitating aspect of ME/CFS10 and COVID-1958. The observed white matter changes in the PI-ME/CFS group appear to be more closely associated with the physical health aspects of the disease, rather than the mental health component, sleep quality, disability level, or disease severity. This suggests that these white matter alterations may be particularly relevant to the physical functioning symptoms experienced by patients, which could reflect the specific impact of neuroinflammation on physical capabilities in post-infectious ME/CFS patients.

A significant positive correlation between AD and mental health score was observed in commissural fibres (body and genu of the corpus callosum) and projection fibres (superior corona radiata, anterior corona radiata) among all participants in the GO-ME/CFS group. This suggests that in ME/CFS patients with gradual onset, lower AD values (potentially indicating axonal degeneration) in these regions are associated with worse mental health status independent of anxiety and depression. The multiple regression result suggests a potential link between white matter axonal damage and previous life-stress-induced mental health issues predisposing to the slow development of ME/CFS in GO-ME/CFS patients. Conducting longitudinal studies, ideally in inception cohorts, and integrating the findings with other neuroimaging data, clinical information, and neuropsychological assessments could lead to a more comprehensive understanding of the biological mechanisms driving these observations.

The distinct WM impairments between the PI-ME/CFS and GO-ME/CFS groups highlight the heterogeneity of ME/CFS. Interestingly, conventional clinical measures (SF‑36, HADS, PSQI and BDS) did not differentiate between the two groups. This discrepancy calls into question the effectiveness of current clinical assessment tools for distinguishing ME/CFS subgroups and highlights the need for more sensitive instruments. Differential correlations in PI- and GO-ME/CFS groups suggested that symptom expression may be driven by divergent underlying mechanisms across subtypes. These findings suggest that a one-size-fits-all treatment approach is unlikely to be effective. Instead, further investigation into the relationship between clinical manifestations and these neurobiological profiles could inform the development of personalised interventions. For instance, patients with post-infectious onset and evidence of neuroinflammation-related white matter changes may benefit from therapies targeting immune dysregulation or neuroinflammation. In contrast, individuals with gradual onset ME/CFS who show signs of possible chronic axonal damage or metabolic stress may require strategies focused on neuroprotection, mitochondrial support, or cognitive rehabilitation. As such, future studies should integrate advanced neuroimaging, clinical phenotyping, and molecular profiling to refine ME/CFS subtypes and identify targeted therapeutic windows.

DTI holds considerable promise as a clinical tool due to its non-invasive nature and sensitivity to microstructural white matter abnormalities. It has been increasingly applied in various neurological and psychiatric conditions to aid diagnosis, prognosis, and disease monitoring59,60. However, routine clinical use remains limited due to variability in acquisition protocols, susceptibility to motion and scanner differences, and the need for expertise in data interpretation61. Efforts toward standardisation and improved reproducibility, such as the use of harmonised multi-site protocols and robust post-processing techniques, are enhancing its clinical viability62,63. While this study focused on characterising white matter microstructural abnormalities in PI-ME/CFS and GO-ME/CFS patients, future research could explore the development of DTI-based classification algorithms incorporating axial diffusivity and other metrics to objectively differentiate subtypes. Such tools, paired with clinical decision frameworks, may enhance diagnostic precision and facilitate personalised management strategies for ME/CFS patients.

This study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the significant associations of AD-PCS in PI-ME/CFS and AD-MCS in GO-ME/CFS groups were lost when the multiple regression analyses were conducted in the patient group. This study did not account for potential confounding factors, such as aetiologies, previous medication usage, or comorbidities. These factors could have affected the observed relationships between AD and clinical measures, particularly within the patient group. The increased heterogeneity in AD and clinical measures among patients, along with the smaller sample size of the patient group compared to the combined group, may have contributed to the loss of significant correlations when analysing patients separately. Future studies should aim to control for these variables or investigate their potential moderating effects on the relationship between WM integrity and ME/CFS. Second, while age-specific mean imputation preserves age-related structure in the data, it does not reflect individual variability within each age group. This may slightly reduce variance in the imputed variables, potentially attenuating associations that rely on this within-group variance. In addition, subgroup analyses based on disease severity within each ME/CFS onset type were unable to be conducted due to limited sample size. Future studies with larger cohorts will be necessary to determine whether the relationship between brain microstructure and symptom burden differs between severity levels in post-infectious versus gradual onset ME/CFS. Furthermore, no biological samples were collected alongside neuroimaging data in this study. As a result, the investigation of potential peripheral biomarkers that may correlate with the observed neuroimaging findings was not possible. Future studies incorporating biological sampling would be valuable for identifying more accessible and cost-effective biomarkers, which could enhance clinical translation and support subtype-specific approaches in resource-limited settings.

In conclusion, this study provides significant insights into the white matter alterations in ME/CFS patients, distinguishing between those with post-infectious (PI-ME/CFS) and gradual onset (GO-ME/CFS). The findings highlight distinct patterns of axial diffusivity (AD) changes in these subgroups, with PI-ME/CFS patients exhibiting increased AD in various association and projection fibres and GO-ME/CFS patients showing decreased AD in commissural fibres. These results suggest different white matter microstructural abnormalities between the two subtypes of ME/CFS and indicate that AD may serve as a sensitive indicator of white matter pathology.

Data availability

The demographics, symptom scores, and preprocessed DTI metrics (FA, MD, AD and RD) of each participant that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Zenodo repository at http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.12791948.

References

Cortes Rivera, M., Mastronardi, C., Silva-Aldana, C. T., Arcos-Burgos, M. & Lidbury, B. A. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive review. Diagnostics 9, 91. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics9030091 (2019).

Zeineh, M. M. et al. Right arcuate fasciculus abnormality in chronic fatigue syndrome. Radiology 274, 517–526. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.14141079 (2015).

Kimura, Y. et al. Brain abnormalities in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: evaluation by diffusional kurtosis imaging and neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging. J. Magn. Reason Imaging. 49, 818–824. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.26247 (2019).

Thapaliya, K., Marshall-Gradisnik, S., Staines, D. & Barnden, L. Diffusion tensor imaging reveals neuronal microstructural changes in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Eur. J. Neurosci. 54, 6214–6228. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.15413 (2021).

Kimura, Y. et al. Free-water‐corrected diffusion and adrenergic/muscarinic antibodies in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Neuroimaging. 33, 845–851. https://doi.org/10.1111/jon.13128 (2023).

Josev, E. K. et al. What Lies beneath: white matter microstructure in pediatric myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome using diffusion MRI. J. Neurosci. Res. 101, 1572–1585. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.25223 (2023).

Chu, L., Valencia, I. J., Garvert, D. W. & Montoya, J. G. Onset patterns and course of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Front. Pediatr. 7, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2019.00012 (2019).

Shan, Z. Y. et al. Multimodal MRI of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: A cross-sectional neuroimaging study toward its neuropathophysiology and diagnosis. Front. Neurol. 13, 954142. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2022.954142 (2022).

Carruthers, B. M. et al. Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: clinical working case definition, diagnostic and treatment protocols. J. Chronic Fatigue Syndr. 11, 7–115. https://doi.org/10.1300/J092V11N01_02 (2003).

Nijs, J. et al. Tired of being inactive: a systematic literature review of physical activity, physiological exercise capacity and muscle strength in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Disabil. Rehabil. 33, 1493–1500. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2010.541543 (2011).

Nedyalkova, D. & Tillé, Y. Bias-robustness and efficiency of model-based inference in survey sampling. Stat. Sin. 22, 777–794. https://doi.org/10.5705/ss.2010.238 (2012).

de Boo, T. M. & Zielhuis, G. A. Minimization of sample size when comparing two small probabilities in a non-inferiority safety trial. Stat. Med. 23, 1683–1699. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1760 (2004).

Freedson, P. S., Melanson, E. & Sirard, J. Calibration of the computer science and applications, inc. Accelerometer. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 30, 777–781. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021 (1998).

Howell, D. C. The treatment of missing data. In The Sage Handbook of Social Science Methodology (Eds. Outhwaite, W. & Turner, S.) 208–224 (Sage, 2007).

Smith, S. M. et al. Tract-based Spatial statistics: Voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. NeuroImage 31, 1487–1505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024 (2006).

Smith, S. M. et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage 23, S208-S219 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051

Fay, M. P. & Proschan, M. A. Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney or t-test? On assumptions for hypothesis tests and multiple interpretations of decision rules. Stat. Surv. 4, 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1214/09-SS051 (2010).

Winkler, A. M., Ridgway, G. R., Webster, M. A., Smith, S. M. & Nichols, T. E. Permutation inference for the general linear model. NeuroImage 92, 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.01.060 (2014).

Nichols, T. E. & Holmes, A. P. Nonparametric permutation tests for functional neuroimaging: a primer with examples. Hum. Brain Mapp. 15, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.1058 (2002).

Olson, I. R., Von Der Heide, R. J., Alm, K. H. & Vyas, G. Development of the uncinate fasciculus: implications for theory and developmental disorders. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 14, 50–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2015.06.003 (2015).

Ramnani, N. The primate cortico-cerebellar system: anatomy and function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 511–522. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1953 (2006).

Cook, D. B. et al. Neural consequences of post-exertion malaise in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Brain Behav. Immun. 62, 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2017.02.009 (2017).

Scardua-Silva, L. et al. Microstructural brain abnormalities, fatigue, and cognitive dysfunction after mild COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 14, 1758. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52005-7 (2024).

Kasahara, K., Hashimoto, K., Abo, M. & Senoo, A. Voxel- and atlas-based analysis of diffusion tensor imaging May reveal focal axonal injuries in mild traumatic brain injury - comparison with diffuse axonal injury. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 30, 496–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2011.12.018 (2012).

Multani, N. et al. The association between white-matter tract abnormalities, and neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms in retired professional football players with multiple concussions. J. Neurol. 263, 1332–1341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-016-8141-0 (2016).

Aung, W. Y., Mar, S. & Benzinger, T. L. Diffusion tensor MRI as a biomarker in axonal and Myelin damage. Imaging Med. 5, 427. https://doi.org/10.2217/iim.13.49 (2013).

HerWeh, C. et al. Quantitative diffusion tensor imaging in herpes simplex virus encephalitis. J. Neurovirol. 13, 426–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/13550280701456498 (2007).

Petersson, I., Hansen, B. M., Svenningsson, A. & Lundstrom, A. Cerebral microvascular injuries in severe COVID-19 infection: progression of white matter hyperintensities post-infection. BMJ Case Rep. 15, e249156. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2022-249156 (2022).

Hornig, M. et al. Distinct plasma immune signatures in ME/CFS are present early in the course of illness. Sci. Adv. 1, e1400121. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.14001 (2015).

Nakatomi, Y. et al. Neuroinflammation in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: an 11C-(R)-PK11195 PET study. J. Nucl. Med. 55, 945–950. https://doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.113.131045 (2014).

Montoya, J. G. et al. Cytokine signature associated with disease severity in chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, E7150-E7158 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1710519114

Almutairi, M. M., Sivandzade, F., Albekairi, T. H., Alqahtani, F. & Cucullo, L. Neuroinflammation and its impact on the pathogenesis of COVID-19. Front. Med. 8, 745789. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.745789 (2021).

Zheng, R. Z. et al. Neuroinflammation following traumatic brain injury: take it seriously or not. Front. Immunol. 13, 855701. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.855701 (2022).

McKee, A. C. et al. The spectrum of disease in chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Brain 136, 43–64. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/aws307 (2013).

Finkelmeyer, A. et al. Grey and white matter differences in chronic fatigue Syndrome–A voxel-based morphometry study. NeuroImage Clin. 17, 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2017.09.024 (2018).

Schmahmann, J. D. & Pandya, D. N. Fiber Pathways of the Brain (Oxford Univ. Press, 2009).

Davis, A. D. et al. White matter indices of medication response in major depression: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging. 4, 913–924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2019.05.016 (2019).

Kubicki, M. et al. Decreased axial diffusivity within Language connections: a possible biomarker of schizophrenia risk. Schizophr Res. 148, 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2013.06.014 (2013).

Lan, M. J. et al. Deficits of white matter axial diffusivity in bipolar disorder relative to major depressive disorder: no relationship to cerebral perfusion or body mass index. Bipolar Disord. 22, 296–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12845 (2020).

Silk, T., Chen, J., Seal, M. & Vance, A. White matter abnormalities in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging. 213, 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.04.003 (2013).

Budde, M. D. et al. Axonal injury detected by in vivo diffusion tensor imaging correlates with neurological disability in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. NMR Biomed. 21, 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.1229 (2008).

Barnden, L. R., Kwiatek, R., Crouch, B., Burnet, R. & Del Fante, P. Autonomic correlations with MRI are abnormal in the brainstem vasomotor centre in chronic fatigue syndrome. NeuroImage Clin. 11, 530–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nicl.2016.03.017 (2016).

Boissoneault, J. et al. Abnormal resting state functional connectivity in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: an arterial spin-labeling fMRI study. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 34, 603–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2015.12.008 (2016).

Morris, G. & Maes, M. Mitochondrial dysfunctions in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome explained by activated immuno-inflammatory, oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways. Metab. Brain Dis. 29, 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-013-9435-x (2014).

Jimenez-Fernandez, S. et al. Oxidative stress and antioxidant parameters in patients with major depressive disorder compared to healthy controls before and after antidepressant treatment: results from a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 76, 13705. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.14r09179 (2015).

Bitanihirwe, B. K. & Woo, T. U. W. Oxidative stress in schizophrenia: an integrated approach. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 35, 878–893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.008 (2011).

Berk, M. et al. Pathways underlying neuroprogression in bipolar disorder: focus on inflammation, oxidative stress and neurotrophic factors. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 35, 804–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.10.001 (2011).

Shrivastava, A., Kar, S. K., Sharma, E., Mahdi, A. A. & Dalal, P. K. A study of oxidative stress biomarkers in obsessive compulsive disorder. J. Obsessive Compuls. Relat. Disord. 15, 52–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2017.09.004 (2017).

Gonsette, R. E. Neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis: the role of oxidative stress and excitotoxicity. J. Neurol. Sci. 274, 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2008.06.029 (2008).

Moylan, S. et al. Oxidative & nitrosative stress in depression: why so much stress? Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 45, 46–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.05.007 (2014).

Gardner, A. et al. Alterations of rCBF and mitochondrial dysfunction in major depressive disorder: a case report. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 107, 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.02188.x (2003).

Prabakaran, S. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in schizophrenia: evidence for compromised brain metabolism and oxidative stress. Mol. Psychiatry. 9, 684–697. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4001511 (2004).

Scaini, G. et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in bipolar disorder: evidence, pathophysiology and translational implications. Neurosci. Biohehav Rev. 68, 694–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.06.040 (2016).

Kishi, T., Sakuma, K. & Iwata, N. Mitochondrial modulators for obsessive–compulsive and related disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 12, 263. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-022-02026-5 (2022).

Su, K., Bourdette, D. & Forte, M. Mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. Front. Physiol. 4, 169. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2013.00169 (2013).

Andersson, J. L., Skare, S. & Ashburner, J. How to correct susceptibility distortions in spin-echo echo-planar images: application to diffusion tensor imaging. NeuroImage 20, 870–888. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00336-7 (2003).

Smith, S. M. & Nichols, T. E. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage 44, 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.061 (2009).

Mao, L. et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan. JAMA Neurol. 77, 683–690. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127 (2020).

Assaf, Y. & Pasternak, O. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)-based white matter mapping in brain research: a review. J. Mol. Neurosci. 34, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12031-007-0029-0 (2008).

Aung, W. Y., Mar, S. & Benzinger, T. L. Diffusion tensor MRI as a biomarker in axonal and Myelin damage. Imaging Med. 5, 427–440. https://doi.org/10.2217/iim.13.49 (2013).

Jones, D. K. & Cercignani, M. Twenty-five pitfalls in the analysis of diffusion MRI data. NMR Biomed. 23, 803–820. https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.1543 (2010).

Zhu, T. et al. Quantification of accuracy and precision of multi-center DTI measurements: a diffusion Phantom and human brain study. NeuroImage 56, 1398–1411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.010 (2011).

Karayumak, S. C. et al. Retrospective harmonization of multi-site diffusion MRI data acquired with different acquisition parameters. NeuroImage 184, 180–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.08.073 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the reviewers for several helpful comments and suggestions, which have led to improvements in the paper. The authors are thankful to all participants who were involved in this study.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) Ideas Grant Scheme (GNT1184219) and The Judith Jane Mason & Harold Stannett Williams Memorial Foundation (The Mason Foundation).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Y., R.A.K., P.D., V.D.C. and Z.Y.S. conceived the project. Q.Y. and Z.Y.S. designed the study. Q.Y., A.B. and Z.Y.S. performed data analysis. Q.Y., R.A.K., P.D., V.D.C., G.A.B., T.Y. and Z.Y.S. interpreted the results. Q.Y. drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed to editing it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, Q., Kwiatek, R.A., Del Fante, P. et al. Distinct white matter alteration patterns in post-infectious and gradual onset chronic fatigue syndrome revealed by diffusion MRI. Sci Rep 15, 24256 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09379-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09379-z