Abstract

Patients with infectious diseases are often at increased risk of anxiety during treatment. The prevalence of anxiety and depression in infected people increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the risk factors for these mental health problems need to be urgently investigated. In this study, a cross-sectional study was conducted in Shanghai in 2022, which included 1283 patients and systematically assessed their sociodemographic characteristics and mental health status. A random forest classifier combined with the Boruta algorithm was used to screen predictors, and a nomogram was constructed based on the screening results. The results of the study showed that entrapment (OR 1.07, 95% CI 1.05–1.09, P < 0.001), defeat (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.07, P < 0.01) and stigma (OR 1.05, 95% CI 1.03–1.06, P < 0.001) were positively associated with anxiety, whereas social support (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.96–0.98, P < 0.001) was negatively associated with anxiety. The C-index of the model was 0.858, the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 0.861 (95% CI 0.834–0.888), and the P value of the Hosmer–Lemeshow test was 0.07, indicating that the model fit well. Based on the Random Forest machine learning method, this study successfully constructed a prediction model for anxiety risk in COVID-19 patients, screening out key risk factors such as feeling trapped, frustration, stigma and social support, providing a scientific basis for clinical practice and public health, and helping to promote personalized interventions for anxiety and the building of a mental health support system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a worldwide epidemic of infectious disease1. Over 676 million individuals around the world have been infected (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html, assessed March, 2023). The COVID-19 global crisis significantly affected various facets of our society, including economic stability, preventive healthcare measures, and notably, the psychological well-being of individuals2. Studies have shown that hospitalised COVID-19 patients were more likely to experience psychiatric disorders during the early stages of the epidemic3, with depression and anxiety being the most common4. One web-based study found that about 20% of participants reported depressive symptoms and 35.1% reported anxiety symptoms during the epidemic5. Another large-scale study of 247,249 people found that the detection rate of depressive symptoms was significantly higher among confirmed patients (20.2%) than among uninfected people (11.3%); poor sleep quality was also more common among confirmed patients (29.4% vs. 23.8%)6. These data highlight the mental health risks faced by COVID-19 patients.

Stress Process Theory (SPT) is a theoretical framework used to explain the emergence and development of stress and its effects on an individual’s health and psychological state, proposed by Pearlin et al. in 1981, the theoretical model emphasises that stress is a dynamic process involving multiple interrelated factors. Based on the stress process theory, public stigma, low social support, coping styles, feelings of entrapment and a sense of defeat are significant psychosocial stressors that can lead to negative mental health outcomes7, and these factors are particularly prominent in patients with infectious diseases. First, people with infectious diseases often face stigma from the public. This stigmatisation not only affects their social lives, but also exacerbates psychological distress. Secondly, due to prolonged isolation from the outside world, hospitalised patients lack support from family, friends and the community, leading to a significant reduction in social support. In addition, feelings of confinement and defeat are common among hospitalised patients, not only because of the limitations of the external environment, but also because of uncertainty about the future8.

Stigmatization refers to the phenomenon of being labeled, stereotyped, and discriminated against due to certain characteristics or identities, leading to social exclusion and devaluation9,10. Perceived defeat is the sense of powerlessness that arises when an individual’s efforts are unsuccessful, due to the loss or disruption of their identity, status, or aspirations11,12. Perceived entrapment is the feeling of being trapped that occurs when an individual cannot escape danger or stress because of a lack of control or external help13. In addition, the mental health could be influenced by how individuals manage challenges or perceived social support5. Coping styles encompass the different approaches and actions that individuals use to cope with the demands and trials of life. These approaches can be broadly grouped into two main categories: problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. Social support, which refers to the psychological and material help one receives from one’s social circle, can help promote a positive sense of self and alleviate negative emotions14,15.

While there have been numerous investigations into anxiety, psychological variables, coping styles, and social support, few studies have examined them in conjunction. This current state of research, to some extent, constrains the comprehensive exploration of systematic predictors for anxiety disorders. To conduct more targeted research, it is essential to identify the factors that have a greater impact on anxiety. The Boruta algorithm is a random forest-based feature selection method designed to determine all important features related to the response variable. In the field of medical research, Boruta’s algorithm is widely used in gene selection, biomarker screening, disease risk prediction, and patient stratification16. Compared with traditional methods, the Boruta algorithm is capable of identifying all important features related to anxiety disorders. It can integrate multiple factors, including psychological variables, coping styles, and social support, to more accurately screen out factors associated with anxiety disorders. Secondly, since the influencing factors span multiple dimensions such as demographics, psychology, physiology, and social support, the Boruta algorithm can better identify potential non-linear relationships among these factors. Additionally, the etiology of anxiety disorders is complex, and there may be high correlations between influencing factors, such as between social support and a sense of defeat. The Boruta algorithm is more robust to collinearity, which can reduce the risk of misjudgment caused by collinearity17. Given the numerous advantages and novelty of the Boruta algorithm, we chose this machine learning method to screen variables and assess their importance. We used the Boruta algorithm to perform a multidimensional analysis combining anxiety, psychological variables, coping styles and social support, which distinguishes us from previous studies.

The aim of this study is to construct a predictive model using a randomised forest approach to explore the associations between specific socio-demographic characteristics (e.g. age, education level, marital status), psychological factors (e.g. entrapment, defeat), level of social support and level of disease-related stigma and anxiety symptoms in patients treated with COVID-19. The model will identify variables that may improve the targeting of anxiety in patients with infectious diseases. By guiding the development of targeted interventions, the model will ultimately improve mental health support for patients treated in hospitals.

Methods

Study Site

A cross-sectional survey was conducted from March to April 2022 among COVID-19 patients in Ruijin Jiahe mobile cabin hospital, which is the first and representative cabin hospital used in Shanghai, with a large number of patients.

Ethics and inclusion statement

The research adhered to the principles laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki. The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee at Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, under the protocol code LL202070. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant named guidelines and regulations. Procedurally, the principle of data minimization is adhered to, where only necessary data is collected to avoid unnecessary privacy risks. Informed consent mechanisms are implemented, requiring participants to provide explicit, voluntary, and informed consent prior to data collection, with the option to withdraw consent at any time. Data retention policies are also established, specifying appropriate retention periods and secure disposal or anonymization practices upon expiration. Anonymization techniques are applied to de-identify personal data, ensuring that collected information cannot be linked back to individuals. Access control mechanisms, including authentication and role-based permissions, further restrict data access to authorized personnel only. During the analysis phase, all data is de-identified to further protect participant anonymity.We conduct regular audits and security checks to ensure that our data security measures are effective and up-to-date. The data will be desensitized by a dedicated person and will only be analyzed by the research team. Study participant names and other personally identifiable information were removed from all text/figures/tables/images. Collectively, these measures demonstrate a commitment to ethical data practices, protecting participant privacy while facilitating responsible research and data utilization.

Participants

The inclusion criteria for participants are: (1) aged over 18 years old; (2) being positive in a SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid test by collecting nasopharyngeal specimens and being identified as individuals with asymptomatic COVID-19 infection; (3) willing to participate and be able to use smartphone; (4) willing to provide informed consent. The exclusion criteria for participants are: (1) having a significant psychiatric condition or a cluster of severe conditions that might lead to heightened levels of anxiety or depression; (2) being pregnant or breast-feeding women; (3) refusing to participate or being unable to ensure compliance. For a detailed recruitment process, please refer to another published study18.

Procedure

A prospective observational study was conducted via the widely used online questionnaire survey platform “Questionnaire Star”. Logical design and validation checks were carried out to ensure that all necessary questions were answered. To confirm the status of COVID-19 patients, the nasopharyngeal swab test was used. We used an RNA isolation kit (Biogerm, Shanghai, China) to extract SARS-CoV-2 RNA from a nasopharyngeal swab specimen of patient. Subsequently, SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection was carried out using a kit designed for SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid detection via real time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). All testing procedures complied with the standard of manufacturer’s instructions.

Measures

A self-reported questionnaire was used to gather participants’ information about sociodemographic characteristics, stigma, social support, and anxiety. Prior research has confirmed the psychometric adequacy of the Chinese-adapted versions of these instruments, with empirical evidence demonstrating satisfactory reliability coefficients and construct validity across multiple Chinese-speaking samples19,20,21. These culturally adapted measures have consistently exhibited strong factorial invariance and predictive validity within Mainland Chinese populations, supporting their contextual appropriateness for assessing relevant constructs in this linguistic and cultural milieu.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Characteristics including age, gender, educational level, marital status, the individual’s COVID-19 vaccination status, diagnosis time (number of days since the nucleic acid abnormality), psychological counseling experience in the past week were collected.

Anxiety

Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) comprises 20 items designed to measure emotional states experienced during the preceding week22. Participants rate each item using a 4-point frequency scale (1 = rarely/never, 4 = always/nearly every day), with total initial scores calculated by summing item responses. These raw scores are converted to adjusted total scores via multiplication by 1.25. The cut-offs for the SAS standard scores were defined as: less than 50, no anxiety; over 50, anxiety. A validated Chinese adaptation of the SAS was employed in this study, with prior research demonstrating satisfactory reliability and construct validity for this translated version across Chinese-speaking populations19,23.

Stigma

Stigmatization was commonly reported in patients with serious infectious diseases and is significantly associated with negative psychological well-being in people with infectious diseases24,25,26. Social Impact Scale (SIS) was used to gauge perceptions of COVID-19-related stigma27. The scale is a widely accepted 24-item assessment tool employed for individuals with significant medical conditions and infectious diseases. The SIS consists of four sections, namely, social rejection which contains nine items, financial insecurity which contains three items,, internalized shame which contains five items, and social isolation which contains seven items. Respondents evaluated each SIS item on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), with cumulative scores ranging from twenty-four to ninety-six. Higher scores denote a more pronounced experience of more severe stigma. The Chinese version of the SIS has been rigorously validated and exhibits robust psychometric properties28,29 (Cronbach α = 0.970).

Entrapment

A meta-analysis was conducted to quantitatively synthesize the existing literature, revealing substantial associations between perceptions of defeat and entrapment and the presence of anxiety disorders30. The Entrapment Scale, a unidimensional instrument, comprises sixteen items with five response choices11. Total achievable scores on this scale range from zero to sixty-four. Elevated scores are indicative of heightened sensations of entrapment (Cronbach’s a = 0.973).

Defeat

A comprehensive review has yielded convergent evidence across multiple designs, participant groups, and measurement instruments, that perceptions of defeat and entrapment are closely associated with anxiety disorders31. The evaluation of “capturing the struggle of failure and feeling of losing rank” usually uses Gilbert and Allen’s Defeat Scale, which comprises of sixteen scales and two dimensions, to evaluate the feeling of defeat in the past 7 days. Higher scores are indicative of a greater tendency to feel defeated in daily life. Scores for positive questions yield positive scores, while scores for negative questions result in negative scores (Cronbach’s a = 0.912).

Coping styles

Research has demonstrated that individuals with elevated anxiety levels are more inclined to adopt emotion-focused coping mechanisms, such as avoidance behaviors, idealization, and self-blame. Conversely, problem-focused strategies like systematic planning and seeking instrumental social support exhibited significant inverse correlations with anxiety severity. The Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire (SCSQ) is a self-report measurement designed to assess coping styles, with a particular focus on problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. The SCSQ provides a comprehensive assessment of both state and trait coping styles, which are relevant to our research questions. The questionnaire consists of 20 items that are divided into two dimensions: positive coping and negative coping. The positive coping aspect encompasses items 1 to12, focusing on attributes associated with effective coping strategies, including "trying to see the good side of things as much as possible, and" finding several different ways to solve problems "; The negative coping dimension consists of items 13 to 20, focusing on attributes associated with negative coping strategies, including "relieving worry through smoking and drinking". After each coping style item, four choices (0, 1, 2, and 3) are listed: not to use, occasionally to use, sometimes to use, and frequently to use (Cronbach’s a = 0.922).

Social support

Social networks provide both affective and instrumental resources that can fortify individuals’ self-concept and diminish emotional distress. These supportive connections, characterized by the exchange of emotional solace and practical aid within interpersonal relationships, serve as critical buffers against negative affectivity while promoting adaptive self-perceptions. Multidimensional Scales of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) instrument32 is used to evaluate participants’ perceived social support stemming from personal relationships (including family, friends, and important person around). Respondents indicated their agreement levels on a 5-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate higher social support (Cronbach’s α = 0.932).

Data analysis

Questionnaire data collection was performed by online questionnaire survey platform “Questionnaire Star”, and variables was exported in .csv format. Descriptive statistical analysis, variable selection analysis, model fitting and testing regression analysis were conducted by IMB Statistics SPSS 26.0 and R (version 3.6.3). To ensure that the version of custom code, software or algorithm described in the publication is maintained, we will publish it as a Supplementary document.

Descriptive statistical analysis

Continuous data were characterized by mean and standard error. Categorical data were described by frequency (percentage). We evaluated the association between anxiety and participants’ categorical sociodemographic characteristics using Fisher’s exact test. Differences in continuous variables between participants with anxiety and those without were evaluated using Mann–Whitney U test. All statistical analyses were two-sided, with a significance threshold set at P ≤ 0.05 to detect notable differences.

Variable selection method: Boruta

The Boruta algorithm can efficiently process datasets with a large number of features (high-dimensional) and nonlinear relationships. In this study, there were multiple independent variables with strong correlation. Unlike other methods that only focus on sorting or excluding individual features, the Boruta algorithm is dedicated to finding all features related to the dependent variable, which helps to gain a more comprehensive understanding of variable relationships in the dataset. In addition, the boruta algorithm can indirectly address collinearity problems to a certain extent and has higher interpretability.

Univariate regression

In univariate selection, we incorporate variables with a P value of ≤ 0.1, which signifies their significance in distinguishing between the anxiety and non-anxiety groups, into the univariate logistic regression analysis. When establishing a predictive model, a P significant level of value ≤ 0.05 are set is established. To evaluate the suitability of a logistic regression model, the Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used. When the P value obtained from the Hosmer–Lemeshow test exceeds 0.05, the model is deemed to exhibit satisfactory goodness of fit.

Development and validation of nomogram

Once the best prediction model was identified, a nomogram was constructed. The nomogram can integrate multiple predictive indicators and transform complex regression equations into visual graphs, making the results of prediction models more intuitive and understandable. They can provide specific prediction probabilities based on individual situations, to assess the risk of anxiety among COVID-19 patients. The performance of the nomogram was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Discrimination was measured using the Concordance index (C-index), which ranges from 0.5 to 1.0, and internal validation was conducted through the bootstrap technique, which involves drawing random samples with replacement from the original dataset and fitting multiple bootstrap samples (in this case, 1000) to obtain a more reliable estimate of the C-index.

Results

Sociodemographic and psychological characteristics

A total of 1283 participants completed the investigation, and basic sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. In this study, 18.78% of participants (N = 241) experienced anxiety. The participant median age was 39 (Interquartile Range 18). Among the study participants, 59.6% were male; 29.4% had received high school education or below, and 73.9% were married. In terms of psychological characteristics, the median scores for entrapment, defeat, stigma, coping styles and social support were 17, 28, 47, 36 and 61, respectively. Additionally, the results of the univariate analysis showed that Age, Entrapment, Defeat, Stigma, Coping styles, Social support and Psychological counseling were associated with anxiety symptoms.

Variables screening

After conducting descriptive statistics, we employed the Boruta algorithm to screen variables that potentially influence anxiety symptoms, thereby determining whether each feature has significant predictive value for the target variable (anxiety symptoms). Each feature in Table 2 reports its importance, normalized hit count and the final decision. The decision indicates that the predictive value of age, educational level, marital status, entrapment, defeat, stigma, coping styles and social support is significant. Among these eight variables, age has a mean importance of 4.55, a median importance of 4.58, and a normalized hit count of 0.88. Marital Status has a mean importance of 3.38, a median importance of 3.29, and a normalized hit count of 0.69. These results suggest that although age and marital status have an impact on anxiety symptoms, their influence is relatively lower compared to other factors.

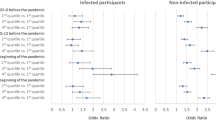

After the preliminary screening was completed, we used eight significant variables as predictors to construct a model through multiple regression analysis, further confirming the influencing factors of anxiety, with the results shown in Table 3. In the final model of this study, although age and marital status showed associations with anxiety symptoms in univariate analyses, they failed to maintain significance in multivariate analyses and were therefore excluded. This may be due to the fact that the predictive value of these variables was relatively attenuated after accounting for other stronger predictors (e.g. feelings of entrapment, defeat, stigma and social support).The Boruta algorithm, while confirming their associations with anxiety, had relatively low significance scores, suggesting that they were limited in their ability to independently predict anxiety. The findings indicate that entrapment, defeat, stigma and social support are significant factors affecting anxiety symptoms. Specifically, entrapment (r = 5.77, P < 0.01), defeat (r = 3.02, P < 0.01) and stigma (r = 6.38, P < 0.01) are significantly positively correlated with anxiety, while social support is significantly negatively correlated with anxiety (r = − 4.60, P < 0.01)..

Model fitting

After two-step variable screening, we built a model using entrapment, defeat, stigma and social support through multiple regression analysis, with the model results presented as Model 2. The results indicated that entrapment (OR 1.07), defeat (OR 1.04), stigma (OR 1.05), and social support (OR 0.97) were significant factors affecting anxiety, with all P value s being less than 0.01. In terms of model evaluation, we first conducted the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. Hosmer–Lemeshow test is a method for assessing model calibration by comparing the observed outcomes with the predicted probabilities: P value greater than 0.05 is generally considered to indicate a good model fit. Model 2 had a P value of 0.07, demonstrating a satisfactory level of model fit. Subsequently, we constructed a nomogram based on Model 2 that includes four variables (entrapment, defeat, stigma and social support), as shown in Fig. 1. The nomogram makes the model’s results more intuitive and understandable, transforming mathematical relationships into a visual format, which is helpful in clinical practice and public health for identifying high-risk patients and assessing disease severity. Finally, we plotted the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, and the results can be seen in Fig. 2. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) is 0.861 (95% CI 0.834–0.888) and the C-index is 0.858, indicating that the model has good predictive performance. AUC and C-index reflect the predictive power of the model, with generally accepted standards that an AUC > 0.7 and a C-index > 0.7 suggest good predictive ability. For instance, in a similar study on predictive model, the AUC and C-index were reported to be 0.866 and 0.78 (95% CI 0.73–0.84)33. Therefore, we believe that this anxiety model has strong predictive capabilities. Although ROC analysis and AUC value can effectively assess the predictive ability of the model, they are not sensitive to category imbalance, cannot provide specific categorization thresholds and do not reflect the calibration of the predictive probability of the model and the effectiveness of its practical application, which is their shortcoming.

Discussion

Anxiety is a very common phenomenon among patients with infectious diseases, especially during hospital treatment. In this study, the participants’ self-rating anxiety scale scores (41.9 ± 9.1) were higher than those of other populations in China (29.78 ± 10.07, n = 1158)34, indicating that patients receiving inpatient treatment are more likely to experience anxiety. This issue deserves more attention and effort to resolve. However, the causes of anxiety vary among individuals, and it is crucial to implement accurate prevention and intervention for each person’s anxiety.

In patients receiving inpatient treatment, increased entrapment and defeat are associated with higher levels of anxiety, which is consistent with findings from previous studies in other populations. In the field of psychology, the interplay between entrapment, defeat and mental health has long been a subject of debate, and their association with anxiety may be related to Involuntary Defeat Syndrome (IDS). IDS is a psychological state associated with stress responses, initially proposed to explain the adaptive behavior of animals facing inescapable threats35. In humans, IDS is considered a manifestation of imbalanced emotional regulation and coping strategies, closely linked to the development of psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression. Research shows that IDS initially serves as a protective mechanism when entrapment and defeat are experienced, but the long-term accumulation of these feelings can lead to a psychological “deactivation” state, ultimately resulting in mental disorders36. Therefore, intervention targeting IDS in patients receiving inpatient treatment is particularly important. Cognitive-behavioral therapy should be initiated to help patients correctly understand the necessity of inpatient treatment and correct their catastrophic thoughts about the disease and isolation. Systematic desensitization combined with mindfulness meditation and relaxation training can then be used to modify patients’ behaviors, while also encouraging them to vent their emotions in safe ways. In addition, ensuring a more comfortable and humane hospital environment, providing entertainment options such as music, sports and cultural activities. Besides, facilitating communication with the outside world can help alleviate feelings of loneliness and abandonment. These specific interventions can help change perceptions, reduce sensitivity to defeat signals and ultimately improve mental health outcomes37,38.

In the study, perceived stigma was found to be significantly positively related to anxiety, which was well demonstrated in the literature. Earlier research conducted among patients recovered from COVID-19 in 2020 reported that individuals with higher stigma scores had a higher chance of experiencing higher levels of anxiety. The present study findings provided support to the previous research on the adverse effect of stigma on individual’s mental health. Also, the finding that social support was negatively associated with anxiety corroborated the previous work during the COVID-19 pandemic in other populations such as front-line nurses and positive patients4. Past studies have suggested that positive social support could help patients improve sleep quality, alleviate psychological distress, and thus reduce the level of negative emotions during the pandemic4. Cultural sensitivity refers to an individual’s ability to perceive and understand the values, beliefs, behaviours and social norms of the cultural context in which they live. In Chinese culture, this sensitivity has a profound effect on stigma and social support. Chinese culture emphasises collectivism and harmony, and individual behaviour and decisions are often influenced by social relationships and group interests. This cultural context makes individuals more sensitive to social evaluations and perceptions of others, which can exacerbate the stigma associated with infectious diseases. On the other hand, this cultural sensitivity also promotes strong social ties, especially in the face of difficulties and challenges, and family and community support can provide important psychological comfort and practical help to individuals. So cultural sensitivity can be a double-edged sword.

Based on the results of this study, we would like to propose targeted interventions to alleviate anxiety symptoms in patients with infectious diseases during treatment. First, psychological interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy and positive thinking meditation were used to help patients adjust negative thought patterns, reduce feelings of entrapment and defeat, and increase psychological resilience. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy39 is a goal-oriented psychotherapeutic approach that aims to identify distorted cognition and establish balanced cognitive patterns. Second, peer support and family support programmes are implemented to strengthen patients’ social support networks, provide emotional support and practical advice, and help patients cope better with the challenges of the treatment process. In addition, the inpatient environment is optimised, recreational activities are increased and more comfortable and humane treatment conditions are provided to reduce patients’ feelings of isolation and confinement. These integrated interventions aim to improve the treatment experience and mental health of infectious disease patients in a holistic manner, addressing multiple levels, including psychological, social and environmental.

In the results of the univariate analysis, we reported the associations between anxiety and demographic factors such as age, education level and marital status. However, these variables were ultimately excluded in the second step of the screening process. This may be because the correlations observed in the univariate analysis no longer held independent predictive value in the multivariate analysis. Nevertheless, in practical applications, these factors can play important roles. On one hand, they can help better identify high-risk populations, determine which groups may need more attention in public health policy-making and facilitate the implementation of preliminary screening efforts. On the other hand, these factors aid in understanding the background characteristics of patients, thereby providing more personalized support. Based on the final model, we aim to visually present the predictive results through the nomogram. In the clinical context, this will facilitate individualized medical decision-making and enhance patients’ and their families’ understanding and compliance with diagnoses and treatments. For instance, it is recommended that cognitive-behavioral therapy be prioritised for patients exhibiting elevated entrapment/defeat scores. In the realm of public health, it will assist in the screening of high-risk populations and the optimization of resource allocation.

This study also has limitations. The present study focuses on COVID-19 patients receiving treatment at Ruijin Jiahe Mobile Cabin Hospital, which was the first and representative mobile cabin hospital in Shanghai, with a large patient volume. However, the influence of Chinese cultural norms, such as collectivism, may significantly shape patients’ experiences with stigma and social support, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings to other regions, populations, or contexts. The study employs a cross-sectional design, which allows for the identification of associations between anxiety, entrapment, defeat, stigma, and social support, but the causal relationships among these variables remain unclear. Additionally, self-reported surveys may be prone to reporting bias compared to face-to-face interviews. Furthermore, anxiety was diagnosed solely using a scale rather than by a psychiatrist due to the isolation environment at the time. Pre-existing mental health conditions, which may confound anxiety symptoms, further limit the explanatory power of the model. For the model, the Boruta algorithm is a suitable choice for feature selection, particularly in complex datasets with potential non-linear relationships and collinearity among variables. However, while internal validation (via bootstrap) is mentioned, external validation using a different dataset was not considered, limiting the generalizability and applicability of the model to other populations or settings. The high AUC value and C-index suggest strong predictive power. The nomogram developed based on the random forest model provides a practical tool for predicting anxiety risk in hospitalized COVID-19 patients, but a deeper discussion of how the model could be integrated into clinical practice is warranted. Psychological interventions, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and positive meditation, may alleviate feelings of entrapment and defeat among patients. While these interventions are supported by the literature, detailed guidance on their implementation in hospital environments is still lacking.

In the future scope of the study, the authors aim to enhance research in several ways. Firstly, diverse patient populations across multiple settings and countries, as well as longitudinal studies, should be included to enhance external validity, track the temporal dynamics of these factors and their impact on anxiety over time, and ensure broader applicability of the results. Secondly, the role of pre-existing mental health conditions, such as depression or anxiety disorders, should be considered as confounding variables in the prediction of anxiety symptoms in infectious disease patients. More objective measurements, such as clinical assessments or physiological markers of stress, should be incorporated to reduce potential bias. Integrating psychological data with biological or physiological markers (e.g., cortisol levels) could enrich the understanding of the underlying mechanisms of anxiety. Additionally, interventional studies are an effective means of addressing the lack of causal validation and facilitating further exploration of the implementation of these interventions in a hospital setting. For instance, what specific approaches should healthcare providers use to incorporate these therapies into routine care? Further exploration of how to integrate peer support, family involvement, and social networks into the treatment process would be beneficial in enhancing the mental health support system for infectious disease patients. Integrating targeted psychological interventions and a more comprehensive mental health support system into the care of infectious disease patients will be essential in improving their overall well-being. To confirm the model’s robustness and applicability, future studies should validate the model with external datasets. The model’s performance may vary across different demographic groups, so assessing its fairness and equity would be valuable for ensuring it works effectively across diverse populations.

Despite these limitations, this study provides a first step towards valid machine-learning-based predictions in anxiety disorders among patients receiving inpatient treatment for infectious diseases. In view of our research results, we suggest paying attention to the anxiety and Involuntary Defeat Syndrome (IDS) among patients receiving inpatient treatment for infectious diseases. During hospitalization, cognitive-behavioral therapy should be provided to correct patients’ cognitive biases and behavioral habits. Additionally, efforts should be made to optimize hospitalization conditions and to increase social support. Emotional therapy should also be employed to help patients vent their emotions and enhance their psychological resilience.

Conclusion

The risk factors associated with anxiety were screened among patients receiving inpatient treatment for infectious diseases through Boruta-selection methods and incorporated filtered risk factors (age, educational level, marital status, entrapment, defeat, stigma, coping styles, and social support) into multiple logistic regression model. The final model included four factors: entrapment, defeat, stigma and social support. The nomogram derived from the multiple logistic regression model showed relatively good efficacy and accuracy, which is contributing to the development of anxiety targeted interventions for patients receiving inpatient treatment for infectious diseases. The key risk factors identified in this study (e.g. feelings of entrapment, defeat, stigma and inadequate social support) provide clinicians with clear targets for intervention. Targeted psychological interventions and social support programmes can effectively reduce patients’ anxiety symptoms and improve treatment adherence and recovery outcomes. In addition, the findings provide a scientific basis for public health policy, which can help to optimise resource allocation and design more effective mental health support programmes. Future research should focus on longitudinal designs, external validation, and multi-modal data collection to enhance the generalizability and practical application of the findings.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code availability

To ensure that the version of custom code, software or algorithm described in the publication is maintained, we will publish it as a Supplementary document.

References

Organization, W. H. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. 2020, March 11. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-atthe-media-briefing-on-Covid-19---11-march-2020 (2020).

The Lancet, P. COVID-19 and mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 8, 87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00005-5 (2021).

Hu, Y. et al. Factors related to mental health of inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Brain Behav. Immun. 89, 587–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.016 (2020).

Yang, X. et al. Social support and clinical improvement in COVID-19 positive patients in China. Nurs. Outlook 68, 830–837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2020.08.008 (2020).

Deng, J. et al. The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID-19 patients: A meta-analysis. Ann. N. Y. Acad Sci. 1486, 90–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14506 (2021).

Magnúsdóttir, I. et al. Acute COVID-19 severity and mental health morbidity trajectories in patient populations of six nations: An observational study. Lancet Public Health 7, e406–e416. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(22)00042-1 (2022).

Adu, J., Oudshoorn, A., Anderson, K., Marshall, C. A. & Stuart, H. Experiences of familial stigma among individuals living with mental illnesses: A meta-synthesis of qualitative literature from high-income countries. J. Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 30, 208–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12869 (2023).

Janoušková, M. et al. Experiences of stigma, discrimination and violence and their impact on the mental health of health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sci. Rep. 14, 10534. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-59700-5 (2024).

Goffman, E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (Simon and Schuster, 2009).

Yuan, K. et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of stigma in infectious diseases, including COVID-19: A call to action. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01295-8 (2022).

Gilbert, P. & Allan, S. The role of defeat and entrapment (arrested flight) in depression: An exploration of an evolutionary view. Psychol. Med. 28, 585–598 (1998).

Gilbert, P. Varieties of submissive behaviour as forms of social defence: Their evolution and role in depression. In Subordination and Defeat: An Evolutionary Approach to Mood Disorders and Their Therapy, 3–45 (2000).

Dixon, A. K. Ethological strategies for defence in animals and humans: Their role in some psychiatric disorders. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 71(Pt 4), 417–445 (1998).

Cohen, S. Social relationships and health. Am. Psychol. 59, 676–684. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676 (2004).

Li, J., Liang, W., Yuan, B. & Zeng, G. Internalized stigmatization, social support, and individual mental health problems in the public health crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 4507. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124507 (2020).

Lai, G., Liu, H., Deng, J., Li, K. & Xie, B. A novel 3-gene signature for identifying COVID-19 patients based on bioinformatics and machine learning. Genes (Basel) 13, 1602. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes13091602 (2022).

Kursa, M., Jankowski, A. & Rudnicki, W. Boruta—A system for feature selection. Fundam. Inform. 101, 271–285. https://doi.org/10.3233/FI-2010-288 (2010).

Chen, H. et al. Social stigma and depression among asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers in Shanghai, China: The mediating role of entrapment and decadence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 13006. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013006 (2022).

Shao, R. et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety and correlations between depression, anxiety, family functioning, social support and coping styles among Chinese medical students. BMC Psychol. 8, 38. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00402-8 (2020).

Li, B., Liu, D., Zhang, Y. & Xue, P. Stigma and related factors among renal dialysis patients in China. Front Psychiatry 14, 1175179. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1175179 (2023).

Chang, R. et al. Feelings of entrapment and defeat mediate the association between self-esteem and depression among transgender women sex workers in China. Front. Psychol. 10, 2241. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02241 (2019).

Zung, W. W. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 12, 371–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0033-3182(71)71479-0 (1971).

Gao, Y. Q. et al. Anxiety symptoms among Chinese nurses and the associated factors: A cross sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 12, 141. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-12-141 (2012).

Nyblade, L., Mingkwan, P. & Stockton, M. A. Stigma reduction: An essential ingredient to ending AIDS by 2030. Lancet HIV 8, e106–e113. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2352-3018(20)30309-x (2021).

Ahmed, A. et al. Stigma, social support, illicit drug use, and other predictors of anxiety and depression among HIV/AIDS patients in Pakistan: A cross-sectional study. Front Public Health 9, 745545. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.745545 (2021).

Alkathiri, M. A., Almohammed, O. A., Alqahtani, F. & AlRuthia, Y. Associations of depression and anxiety with stigma in a sample of patients in Saudi Arabia who recovered from COVID-19. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 15, 381–390. https://doi.org/10.2147/prbm.S350931 (2022).

Fife, B. L. & Wright, E. R. The dimensionality of stigma: A comparison of its impact on the self of persons with HIV/AIDS and cancer. J. Health Soc. Behav. 41, 50–67 (2000).

Yuan, Y. et al. COVID-19-related stigma and its sociodemographic correlates: A comparative study. Global Health 17, 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-021-00705-4 (2021).

Pan, A.-W., Chung, L., Fife, B. L. & Hsiung, P.-C. Evaluation of the psychometrics of the Social Impact Scale: A measure of stigmatization. Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 30, 235–238 (2007).

Taylor, P. J., Gooding, P., Wood, A. M. & Tarrier, N. The role of defeat and entrapment in depression, anxiety, and suicide. Psychol. Bull. 137, 391–420. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022935 (2011).

Dixon, A. K. Ethological strategies for defence in animals and humans: Their role in some psychiatric disorders. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 71, 417–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1998.tb01001.x (1998).

Osman, A., Lamis, D. A., Freedenthal, S., Gutierrez, P. M. & McNaughton-Cassill, M. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support: Analyses of internal reliability, measurement invariance, and correlates across gender. J. Pers. Assess 96, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.838170 (2014).

Lei, W., Wang, W., Qin, S. & Yao, W. Predictive value of inflammation and nutritional index in immunotherapy for stage IV non-small cell lung cancer and model construction. Sci. Rep. 14, 17511. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66813-4 (2024).

Li, L., Wang, B. Q., Gao, T. H. & Tian, J. Assessment of psychological status of inpatients with head and neck cancer before surgery. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi 53, 21–26. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1673-0860.2018.01.005 (2018).

Gilbert, P. & Allan, S. The role of defeat and entrapment (arrested flight) in depression: An exploration of an evolutionary view. Psychol. Med. 28, 585–598. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291798006710 (1998).

Price, J., Sloman, L., Gardner, R. Jr., Gilbert, P. & Rohde, P. The social competition hypothesis of depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 164, 309–315. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.164.3.309 (1994).

Griffiths, A. W., Wood, A. M., Maltby, J., Taylor, P. J. & Tai, S. The prospective role of defeat and entrapment in depression and anxiety: A 12-month longitudinal study. Psychiatry Res. 216, 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.01.037 (2014).

Johnson, J., Gooding, P. & Tarrier, N. Suicide risk in schizophrenia: explanatory models and clinical implications, The Schematic Appraisal Model of Suicide (SAMS). Psychol. Psychother. 81, 55–77. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608307x244996 (2008).

Stallard, P. Evidence-based practice in cognitive-behavioural therapy. Arch. Dis. Child 107, 109–113. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2020-321249 (2022).

Funding

This work was support by Shanghai Three-Year Action Plan for Public Health under Grant (GWVI-11.1–29) and Science and Technology Commission Shanghai Municipality (No.20JC1410204) for the Seroepidemiological Study of Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia in Key Populations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Tian Shen, Ying Wang and Yong Cai guided the design of this study. Ruijie Chang and Dake Shi did the investigation. Ruijie Chang and Chenrui Li did the formal analysis, wrote the main manuscript text, and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Technical appendix

Technical appendix

The Boruta algorithm is built upon the similar principle that underlies the random forest classifier: the effects of random noise and correlation are mitigated by introducing randomness into the system and aggregating results from multiple random samples. The following sequential steps are taken to apply the Boruta algorithm: first, the information system is expanded by duplicating all thirty-one variables. Then, the additional attributes undergo a process to eliminate any correlation with the response variable. The random-forest classifier is applied to the extended information system, and the resulting Z scores are computed for all attributes. Next, the maximum Z score among the shadow attributes is determined, and each attribute that scored better than this maximum is marked as “important”. For each attribute with undetermined importance, a two-sided test of equality with the maximum Z score is performed. Attributes whose importance is deemed significantly lower than the maximum are removed from the information system, while those deemed significantly higher are marked as “important”. Finally, all shadow attributes are eliminated, and the procedure is repeated until importance is assigned to all attributes, or to a previously set limit of random forest runs is reached.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, R., Li, C., Shi, D. et al. Predicting factors associated with anxiety by patients undergoing treatment for infectious diseases using a random-forest machine learning approach. Sci Rep 15, 32074 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09470-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09470-5