Abstract

Square in square concrete-filled double-skin steel tube (CFDST) columns are widely preferred on account of their convenient nodal structural form and efficient construction process. In order to investigate the axial compression behavior of the columns after lateral impact, a precise numerical model for the post-impact axial compression of square in square CFDST columns was established using the finite element package, and was validated by existing experiments and studies. The residual axial compression bearing capacity of the columns after lateral impact has been analyzed. The typical vertical load–axial displacement curve, the failure mode and stress distribution of the columns have been studied. The parametric analysis has been also carried out to explore the influence of key parameters. Lastly, based on the parametric analysis, a simplified formula has been proposed to estimate the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the columns. The results show that under lateral impact, the columns generally exhibit a flexural failure mode. Local indentation occurs at the impact location, and buckling also appears at the bottom of the fixed support section. The coefficient of residual axial compression bearing capacity decreases with the increase of impact energy, slenderness ratio, and concrete strength, and increases significantly with the increase of steel strength.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

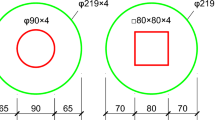

The concrete-filled double-skin steel tube (CFDST) column, which is a composite structural form, consists of two concentric steel tubes and concrete sandwiched between the inner and outer steel tubes. This structural form is highly favored due to its light weight, outstanding seismic performance, high stiffness, and remarkable load-bearing capacity1,2,3,4,5. The interaction between the steel tubes and the concrete leads to a mutual improvement of their properties. Specifically, the steel tubes not only enhance the strength and ductility of the concrete but also the concrete effectively postpones the local buckling of the steel tubes. The hollow interior section of the CFDST column endows it with a distinct advantage in a variety of engineering applications, especially in terms of pipeline layout and transportation. Among the diverse cross-sectional shapes, the square in square CFDST columns, with the cross-sectional form illustrated in Fig. 1, are widely preferred on account of their convenient nodal structural form and efficient construction process. The square tube exhibits excellent bending stiffness when subjected to forces, thereby making it an optimal choice for scenarios demanding high bending performance6,7.

With the acceleration of urbanization, the frequency of impact accidents pertaining to infrastructure is progressively increasing. The impacts can be instigated by a multitude of factors such as vehicles, vessels, falling rocks, and debris resultant from explosions8,9,10. Such incidents not only imperil human life but also pose a substantial threat to property safety. The occurrence of these accidents commonly leads to irreversible structural impairment and, in more extreme circumstances, can even instigate catastrophic structural collapses, thereby incurring inestimable losses. Therefore, impact-resistant design assumes an exceedingly crucial position in the structural design of infrastructure. Particularly, low-velocity impacts, notwithstanding the fact that they may not inevitably culminate in the total collapse of a structure, often exert a non-trivial influence on the short-term safety performance and long-term durability of the structure11,12. To effectively attenuate the losses occasioned by these impact accidents, the impact resistance of structures should be duly considered during the structural design phase. Moreover, an appraisal of the damage to structures subsequent to accidents is indispensable for the timely enactment of repair measures. Research on the residual load-bearing capacity of structures following impacts is of cardinal significance for the formulation of cost-efficient reinforcement and repair strategies, which bears profound implications for augmenting the impact resistance of infrastructure.

Some research has been conducted on square in square CFDST columns. Handousa et al.13 investigate the influence of inner and outer plate tubes (flat or corrugated plates) on the axial compressive behavior of square in square CFDST columns, and found that incorporating internal corrugated plates notably improved both the load-carrying capacity and ductility of the columns. Chen et al.14 carried out the experimental and simulation study on compression-torsion mechanical properties of square in square CFDST columns. The results show that the torsional ultimate bearing capacity increases as the strength of steel or concrete increases. Wang et al.15 carried out an experiment of the blind bolted connections with square in square CFDST columns under seismic loads. The influence of end plate type, hollow ratio of column and demountable composite floor was analyzed. The results show that the blind bolted connections with square in square CFDST columns have good seismic performance and ductility. Shi et al.16 conducted a numerical study utilizing finite element software to investigate the influences of different cross-sectional shapes and initial geometric imperfections on the impact performance of CFDST columns. Wang et al.17,18 carried out finite element analysis (FEA) studies to explore the influence of various parameters on the damage modes, impact forces, and deformation patterns of the test specimens. The results indicated that CFDST straight tubes have better impact resistance compared to conical tubes. Aghdamy et al.19,20 carried out parametric analyses on the impact performance of CFDST columns, making comparisons with experimental results. The findings indicated that during impact incidents, the initial impact velocity exerts the most significant influence on the impact response of a CFDST column. Zhao et al.21 performed a series of experiments to assess the impact resistance of CFDST columns with externally applied stainless steel. Based on the experiment results, a coupled axial force-impact model for stainless steel CFDST was developed22 to establish an extensive database and a formula for calculating the power amplification coefficient of the impact force plateau value was put forward. Yan et al.23 investigated the residual axial properties of CFDST K—joints after lateral impact and put forward a calculation method for the residual loading capacity of CFDST—K joints to evaluate the damage degree.

Considering that square in square CFDST columns can be well applied in the construction of tall bridge piers, wind turbine towers, etc. These structures may be laterally impacted by falling rocks and vessels during their service life. Whether the square in square CFDST columns can continue to bear the vertical loads after being impacted will affect the safety of the bridges and the wind turbines. Therefore, it is of great significance to analyze the residual axial compression bearing capacity of square in square CFDST columns after lateral impact. However, to my existing knowledge, few research studies have been conducted on the residual bearing capacity of square in square CFDST columns after lateral impact. Thus, there is an urgent need to investigate the axial compression behavior after lateral impact and the influencing factors, which are crucial to the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the structure. In this paper, a precise finite element model of square in square CFDST columns under lateral impact has been developed using FE package ABAQUS (Version 2022). Then, the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the columns after lateral impact has been analyzed by comparing the simulation and experiment results. Furthermore, the typical vertical load–axial displacement curve, the failure mode and stress distribution of the columns have been studied when the columns were subjected to axial compression following a lateral impact. In addition, the parametric analysis has been also carried out to explore the influence of key parameters such as the hollow ratio, the slenderness ratio, the concrete strength, the steel strength, and the impact energy. Lastly, based on the parametric analysis, a simplified formula has been proposed to estimate the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the columns after lateral impact.

Numerical method

General description

A total of 13 specimens of square in square CFDST column have been designed. The detailed information and loading conditions of the specimens are shown in Table 1. Among them, Bo and Bi represent the side lengths of the outer and inner steel tubes respectively; to and ti denote the wall thicknesses of the outer and inner steel tubes respectively; L is the length of the column specimen; fc is the compressive strength of concrete cubes; fyo and fyi are the yield strengths of the outer and inner steel tubes respectively. Based on the above, the following is deduced. The slenderness ratio of the column specimens is denoted as λ, which can be expressed as

The hollow ratio is denoted as χ, which can be expressed as

The compressive state ratio is denoted as n, which can be expressed as

The parameter n reflects the compressive state of the column before impact. During the impact loading stage, on the basis of keeping the mass of the impactor unchanged at 650 kg, different impact energy loadings were achieved by adjusting the impact velocity v0.

In order to discuss the effect of lateral impact on the axial compression bearing capacity of the columns, it is necessary to first obtain the initial axial compression bearing capacity of the columns before impact loading. In this study, the finite element simulation and the method recommended by the code are respectively used to calculate this bearing capacity. Of the two values, the value obtained from the numerical simulation is denoted as NFE, and that calculated according to the recommended formula is denoted as Nuc.

Technical specification for concrete-filled double skin steel tubular structures (T/CCES 7-2020)24 recommends the calculation method for the initial axial compression bearing capacity of square CFDST columns before impact. The method takes into account the stability coefficient of long column members, and the calculation formula is as follows:

In this formula, Nosc,u represents the ultimate bearing capacity of the outer steel tube and the sandwich concrete; Ni,u represents the ultimate bearing capacity of the inner steel tube; and φ represents the stability coefficient of the axially compressed column.

The ultimate bearing capacity of the outer steel tube and the sandwich concrete takes into account the confinement effect of the outer steel tube and is calculated using the following formula:

In this formula, Aso and Ac are the cross-sectional areas of the outer steel tube and the sandwich concrete respectively; and fosc is the combined axial compressive strength of the outer steel tube and the sandwich concrete, which can be expressed as follows:

where fo is the yield strength of the outer steel tube; fc is the axial compressive strength of concrete; ξ0 represents the nominal confinement effect coefficient, which can be expressed as follows:

where Ace is the nominal cross-sectional area of the sandwich concrete, and can be expressed as Ace = (B0 − 2t0)2 for square in square CFDST; C1 and C2 can be expressed as follows, respectively:

where α is the sectional steel ratio, and can be expressed as α = Aso/Ac; and αn is the nominal sectional steel ratio, and can be expressed as αn = Aso/Ace.

The ultimate bearing capacity of the inner steel tube is calculated using the following formula:

In this formula, fi and Asi are the yield strength and the cross-sectional area of the inner steel tube.

The stability coefficient of the columns is calculated using the following formula:

In this formula, the slenderness ratio of the square in square CFDST column can be specifically expressed as follows:

Moreover, a, b, and c are calculation coefficients. The basis for determining their respective values can be found in detail in the technical specification24.

Material constitutive model

Steel

Both the inner and outer steel tubes are fabricated from low-carbon steel, and the stress–strain constitutive relationship under uniaxial loading employs the five-stage plastic model25. As depicted in Fig. 2, this model consists of five stages. fp, fy, and fu are the proportioned limit strength, the yield strength, and the ultimate strength of the steel material, respectively. The corresponding strain values can be obtained by ε1 = 0.8fy/Es, ε2 = 1.5ε1, ε3 = 10εy, and εu = 100εy. Additionally, the elastic modulus (Es), Poisson’s ratio (v), and density (ρ) of the steel are taken as 206 GPa, 0.3, and 7850 kg/m3, respectively.

Under the effect of low-velocity impact loads, the strength of steel increases with the growth of the strain rate. Thus, the Cowper–Symonds model26 is employed to calculate the dynamic steel strength enhancement factor at low strain rates, as shown in the following equation:

In this formula, \(f_{{\text{y}}}^{{\text{d}}}\) represents the yield strength of steel at a particular strain rate \(\dot{\varepsilon }\), and \(f_{{\text{y}}}\) is the yield strength of steel obtained from tensile tests. The values of parameters D and p are taken as 6844/s and 3.91, respectively27.

Concrete

The concrete material is simulated by using the plastic damage model, and the values of the basic parameters are set as follows: the density is 2500 kg/m3, the elastic modulus is calculated as 4700 \(\sqrt {f_{{\text{c}}}^{\prime } }\)28, and the Poisson’s ratio is taken as 0.2. According to the suggestions in the literature29, the parameters dilation angle (φd), eccentricity (e), ratio of the compressive strength in the biaxial state to the uniaxial compressive strength (αf), K parameter (Kc) and viscosity (μ) in this simulation are assigned the values of 30°, 0.1, 1.16, 0.667 and 3 respectively. In addition, Huang et al.30 discovered that the confinement effect of inner and outer tubes on the sandwich concrete in CFDST columns is highly similar to that observed in concrete-filled steel tube (CFST) columns. Therefore, the compressive stress–strain model for concrete in CFST columns is adopted in this study31, and the specific relationship is as follows:

In this formula, x and y represent the states of strain and stress, and can be specifically expressed as x = ε/ε0, and y = σ/σ0. σ0 is the cylindrical compressive strength of concrete, and ε0 can be calculated as ε0 = εc + 800·ς0.2·10–6, in which \(\varepsilon_{{\text{c}}} = (1300 + 12.5f_{{\text{c}}}^{\prime } ) \cdot 10^{ - 6}\). For square in square CFDST column, the coefficients η and β0 can be calculated as Eqs. (15) and (16).

Under the action of dynamic loads, the influence of strain rate on the concrete strength is calculated by using the CEB model32, as shown in Eq. (17).

where fd is the dynamic compression strength when the strain rate is \(\dot{\varepsilon }_{{\text{d}}}\), fcm is the static compression strength, \(\dot{\varepsilon }_{{\text{s}}}\) is the quasi-static strain rate in compression, and the value is − 30 × 10−6/s. The coefficient α can be calculated \(\alpha = 1/(5 + 9(f_{{{\text{cm}}}} /f_{{{\text{cm0}}}} ))\), in which the value of fcm0 is 10 MPa.

Boundary and element

Figure 3 is a schematic diagram of the finite element model. The inner and outer steel tubes and the sandwich concrete components are created using eight-node linear reduced integration three-dimensional solid elements, while the drop hammer is simplified as an analytical rigid shell element with an impact surface measuring 200 mm × 80 mm. The normal direction contact between the steel tube and the sandwich concrete, as well as between the drop hammer and the outer steel tube, is simulated by means of “Hard” contact, and the tangential contact is simulated using the Coulomb friction model. The friction coefficient μsc between the steel tubes and sandwich concrete is taken as 0.6, and the one between the outer steel tube and drop hammer is 0, respectively27. Coupling points RP1 and RP2 are established at both ends of the component, and the displacement and rotation angles of these coupling points are constrained. The axial displacement of RP1 is released (Uy = Uz = URx = URy = URz = 0), and an axial force is applied at point RP1, which is simulated by a spring. RP2 constrains displacements and rotation angles in all directions (Ux = Uy = Uz = URx = URy = URz = 0). Impact mass and initial velocity, v0, are added to the drop hammer through creating a node set. The structured mesh generation technique is utilized for global uniform element division, and in order to improve the efficiency and accuracy of the calculation results, a grid size of approximately 22.5 mm is employed.

Loading and analysis

The loading and analysis process of the model are depicted in Fig. 4. At the first stage, a static axial compression model of the square in square CFDST column is established as shown in Fig. 3, and the initial bearing capacity of the un-impacted column, NFE, is obtained through the ABAQUS/Standard analysis step algorithm. The first-order buckling mode from modal analysis is introduced to simulate the initial geometric defect of the column, with the defect coefficient set at 1/1000 of the rod length33.

At the second stage, a square in square CFDST column with axial force coupled impact model is established. Firstly, the axial force is applied to the column by using the ABAQUS/Standard analysis step, and then the model with the applied axial force is imported into the impact model. The dynamic constitutive model described above is employed for the material constitutive, and the ABAQUS/Explicit analysis step algorithm is utilized for calculation. After the lateral impact is completed, the damaged column after impact is imported into a new model as the initial state, linking the structural deformation and stress state of the column from the previous step. The material model is replaced by the static constitutive model, and axial displacement is applied at one end of the column for loading, thereby the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the column, Nd, can be obtained after lateral impact.

In order to avoid problems such as the inability to converge in calculations due to large geometric deformations of the column after impact, ABAQUS/Explicit is used for quasi-static analysis. The loading rate is an important factor affecting the accuracy of the quasi-static analysis results. Typically, the ideal loading time is 10 times the period of the lowest-order modal,29.

Verification

To my existing knowledge, experimental studies on the axial compression of CFDST after impact are extremely rare, while experimental studies on the impact and axial compression of CFST are very abundant. Therefore, based on previous experiments and research, the developed numerical models, including the long column static axial compression model, the lateral impact model, and the post-impact axial compression model, are gradually verified for their accuracy.

Axial compression model

To verify the accuracy of the static axial compression model, the model was used to simulate the axial compression loading tests of the CFDST specimens in the studies of Tao et al.35, Han et al.36, Cong et al.37, and Wang et al.38. The comparison of the axial compression bearing capacity between the simulation results, NFE, and the test results, Ntest, is shown in Fig. 5. It can be seen from Fig. 5 that, except for a few components, the errors of the simulation results of most specimens are within 5%. The axial compression model has a high degree of accuracy. In addition, the simulated value of the axial compression bearing capacity of the un-impacted column is compared with the calculated value from Eq. (4). The comparison results are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 5. It can be seen that the error for most specimens between the simulated value of the initial axial compression bearing capacity, NFE, and the calculated value of the formula, Nuc, is less than 5%, and the simulation result is in good agreement with the formula calculation result.

Lateral impact model

The verification of the lateral impact model is performed by utilizing the data of several typical specimens in existing impact tests of CFST and CFDST. The specific column parameters are shown in Table 2. The cross-sectional shapes of the specimens include circular27, square34, and circular-in-circular17. Comparisons are made from aspects such as the time-history curves of impact force (F), the time-history curves of mid-span deflection (Δ), and the impact failure modes of the specimens. Figure 6 shows the comparison of the time-history curves between the finite element results and the test ones. The curves in the figure have a high degree of shape and trend matching, and the errors of the peak impact force, the impact force plateau value, and the peak deflection of the columns are all within 10%. Figure 7 shows the comparison of the overall failure modes between the simulation and the test. The local depressions and overall deformations simulated by the finite element are fundamentally consistent with the test phenomena.

Post-impact axial compression model

The comparative verification of the post-impact axial compression model was carried out on typical specimens in literature39. The specific parameters are shown in Table 2. Figure 8 shows the comparison of vertical load–axial displacement curves and vertical load–lateral displacement curves of the columns after lateral impact. The curves are generally in good agreement, and the maximum error between the finite element simulated value and the test value of the residual axial compression bearing capacity is about 14%.

Based on the above verification results, the modeling process of this research is highly feasible. The established finite element model has high accuracy in impact response and axial compression after lateral impact, and can be used for subsequent analysis of the axial compression mechanism and parameters of square in square CFDST columns after lateral impact.

Behavior of axial compression after impact

Using the finite element model established above, the typical vertical load–axial displacement curve, the failure mode and stress distribution of the square in square CFDST columns are analyzed. The parameters of the columns are as follows: L = 1800 mm, Bo = 180 mm, Di = 87 mm, to = 3 mm, ti = 3 mm, v0 = 7 m/s, m = 650 kg, fc = 50 MPa, and fy = 350 MPa.

Vertical load–axial displacement curve

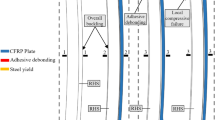

Figure 9 shows the typical vertical load–axial displacement curve of the CFDST column after lateral impact, which also represents the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the column. The residual bearing capacity of the sandwich concrete, as well as that of the inner and outer steel tubes, is also included in Fig. 9. Different from the un-impacted column, the curves after lateral impact generally go through three stages, the ascending stage, the peaking stage, and the declining stage, respectively. For the convenience of analysis, four characteristic points are marked on the load–displacement curve of the CFDST column. Point A marks the starting point of axial loading after lateral impact, Point B marks the entry into the elastoplastic stage, Point C marks the ultimate bearing capacity, and Point D marks the end of the simulation. It can be observed from the figure that the overall curve of the column develops linearly in the AB stage. At this time, the column is in the elastic stage, and no significant deformation occurs in the column. In the BC stage, the load borne by the core concrete reaches the peak load first, and then gradually decreases. The loads borne by the inner and outer steel tubes keep increasing, so that the overall bearing capacity of the column continues to rise for a certain period after the bearing capacity of the concrete decreases. With further loading, the column reaches the ultimate bearing capacity, Nd (Point C). Subsequently, the bearing capacity of the column decreases, and the curve enters the descending stage. In the CD stage, the bearing capacities of the inner and outer steel tubes continue to rise, and the bearing capacity of the column decreases slowly.

Failure mode and stress distribution

Figure 10 shows the failure mode and stress distribution of the typical column under axial compression after lateral impact. Under lateral impact load, the square in square CFDST columns generally exhibit a flexural failure mode. Local indentation occurs at the impact location, and buckling also appears at the bottom of the fixed support section. Three plastic hinges emerge near the impact position and the two fixed supports. For the convenience of analysis, different sides of the column are marked. The side where the impact occurs is marked as Side M, the side opposite to the impact side is marked as Side N, and the two sides on the left and right of the impact side are symmetrical and marked as Side K. Figure 10a,b are the stress distributions of the outer and inner steel tubes, respectively. For the damaged column after impact (Point A), residual stress is distributed in various parts of the column, and plastic hinges are formed at the impact position at the mid-span and at the two ends of the support. The failure modes and stress distributions of the inner and outer steel tubes are extremely similar. In terms of the failure mode, the outer steel tube mainly undergoes local depression at the mid-span and overall bending deformation, while the inner steel tube, protected by the concrete, mainly undergoes overall bending failure. In terms of stress distribution, the stress of the inner and outer steel tubes is mainly concentrated on the left and right sides of the impact surface at the mid-span (Side K) and at the supports. The reason is that the deformation speeds of the impact side (Side M) and the side opposite (Side N) to the impact side are different during the impact. The steel tube in the mid-span cross-section (Side K) extrudes outward and buckles. At this time, the stress value in a small area of the column exceeds the yield strength of the steel tube 350 MPa, but does not exceed its ultimate tensile strength 560 MPa, indicating that these steels have not completely failed.

In the AB stage, the column experiences a short elastic stage, with no significant deformation occurring, and the stress at each part gradually increases. When the column enters the peaking stage (Point B), the maximum stress is mainly concentrated on Side M (the impact side at the mid-span), because the mid-span of the column is more vulnerable after being impacted. In the BC stage, with the increase of the load, the overall bending deformation of the column further increases, and local buckling occurs around the impact position and at the two ends of the support. The stress on Side M (the impact side at the mid-span) and at the two ends of the support both expand to Side K. When the column reaches the ultimate bearing capacity (Point C), the stress in most areas of the inner and outer steel tubes has exceeded the yield strength and ultimate tensile strength of the material. In the CD stage, the local buckling and overall bending of the column become more obvious, and finally, the column undergoes instability failure.

Figure 10c shows the longitudinal stress distribution of the sandwich concrete cross-section at the mid-span. Tensile stress is shown as positive, and compressive stress is shown as negative in this figure. At the beginning of axial compression loading (Point A), the stress distribution is non-uniform. The area in the middle of the cross-section at the mid-span is under tension. At this time, the stress on the impact side (Side M) is relatively small, while the stress on the side opposite to the impact side (Side N) is relatively large. The stress is mainly concentrated at the contact area between the concrete on Side N and the outer steel tube. This is because the concrete and the steel tube are in full contact and extrusion under the impact. With the application of axial load, the overall bending deformation of the column increases, and the inner and outer steel tubes undergo buckling. The stress on Side M (the impact side) and on the left and right sides of the impact side (Side K) keeps increasing. When the column reaches the ultimate bearing capacity (Point C), due to the strong confinement of the outer steel tube on the corners of the concrete, stress concentration occurs at the corners of the concrete. After the peak load, the longitudinal stress changes to a state of relatively low stress.

Parameter analysis of N d

Influence of hollow ratio

Figure 11a shows the vertical load–axial displacement curves of the square in square CFDST columns with different hollow ratios after lateral impact. As shown in the figure, the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the column after lateral impact decreases with the increase of the hollow ratio. However, the difference in bearing capacity is not significant. Compared with the case when the hollow ratio χ = 0.3 (Nd = 1156.45 kN), the change range of the residual axial compression bearing capacity when χ = 0.5 (Nd = 1191.03 kN) and χ = 0.7 (Nd = 1228.28 kN) does not exceed 10%. It can be seen that the change of the hollow ratio has a relatively small effect on the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the components after impact. There are mainly two reasons for this, on the one hand, the increase of the hollow ratio will reduce the flexural performance of the cross-section and weaken the ability of the column to resist impact deformation, which has a negative impact on the residual bearing capacity. On the other hand, with the increase of the hollow ratio, under the impact load, the deformation of the column gradually changes from overall bending deformation to local deformation at the mid-span, reducing the eccentricity of the column during the axial compression loading after impact, which is beneficial to the improvement of the residual bearing capacity of the component.

Influence of slenderness ratio

Figure 11b shows the vertical load–axial displacement curves of the columns with different slenderness ratios after lateral impact. The residual axial compression bearing capacity of the columns almost shows a linear downward trend with the increase of the slenderness ratio. Compared with the cases when λ = 21.06 (Nd = 1275.84 kN) and λ = 31.59 (Nd = 1191.03 kN), the residual bearing capacity when λ = 42.12 (Nd = 1047.04 kN) is reduced by 17.9% and 12.1% respectively. This is because as the length of the column increases, its own stability deteriorates. At the same time, the constraints of the two ends of the support on the mid-span of the column specimen weaken during impact. The overall deformation of the column specimen after impact increases with the increase of the slenderness ratio, which further increases the instability of the column specimen, resulting in a decrease in the residual axial compression bearing capacity. It can be seen that the increase in the slenderness ratio has an adverse effect on the impacted column specimens. Reducing the slenderness ratio of the columns, which can be achieved by increasing the cross-section area or reducing the effective length of the column, can effectively improve the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the column after lateral impact.

Influence of concrete strength

Figure 11c shows the vertical load–axial displacement curves of the column with different concrete strengths after lateral impact. Under the same impact loading, the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the column also increases with the increase of concrete strength. The residual bearing capacity when fc = 70 MPa (Nd = 1288.32 kN) is increased by 18.5% and 8.2% respectively compared with the cases when fc = 30 MPa (Nd = 1087.14 kN) and fc = 50 MPa (Nd = 1191.03 kN). The increase in concrete strength is beneficial to the subsequent load—bearing of the square in square CFDST column after lateral impact.

Influence of steel strength

Figure 11d shows the vertical load–axial displacement curves of the column with different steel strengths after lateral impact. Similar to the case of concrete, the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the column increases significantly with the increase of steel strength. The residual bearing capacity when fy = 420 MPa (Nd = 1396.90 kN) is increased by 44.1% and 17.3% respectively compared with the cases when fy = 280 MPa (Nd = 969.60 kN) and fy = 350 MPa (Nd = 1191.03 kN). Steel has a relatively significant effect on improving the residual axial load–bearing capacity. With the increase of steel strength, the ability of the column to resist impact deformation is significantly enhanced, which leads to the improvement of the residual axial compression bearing capacity.

Influence of impact energy

Figure 11e shows the vertical load–axial displacement curves of the column with different impact energies after impact. With the increase of impact energy, the residual axial compression bearing capacity is significantly reduced, and the ductility is remarkably improved. The greater the impact energy, the smaller the residual axial compression bearing capacity. When the impact velocity increases from v = 5m/s to v = 7m/s and v = 9m/s, the residual bearing capacity of the column decreases by 14%, 33%, and 48% respectively compared to that of the un-impacted column NFE. This is because the increase in external energy forces the column to absorb more energy during the impact process. The lateral displacement of the column increases, and when vertically loaded, the column is more likely to form an eccentric compression failure mode, resulting in a reduction in the residual bearing capacity.

Simplified formula

After being lateral impacted, the column does not completely fail and still has a certain axial compression bearing capacity. Therefore, during the impact-resistant design, in order to ensure that the column does not suffer severe damage or collapse under certain impact conditions, it is necessary to clarify some quantitative indicators to predict the impact-resistant performance of the column under different impact energies. According to references40, the coefficient of residual axial compression bearing capacity, nd, after impact is defined as shown in Eq. (18):

In the formula, Nd is the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the damaged column after lateral impact; Nu is the initial axial compression bearing capacity of the un-impacted column, and in this case, the calculated value Nuc from Eq. (4) is adopted.

Figure 12 shows the relationships of the influence of various parameters on the coefficient of residual axial compression bearing capacity. As shown in Fig. 12, parameters such as the hollow ratio, slenderness ratio, concrete strength, steel strength, and impact energy all have a certain effect on the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the square in square CFDST column after lateral impact. The coefficient of residual axial compression bearing capacity decreases with the increase of impact energy, slenderness ratio, and concrete strength, and increases with the increase of hollow ratio and steel strength.

By simultaneously fitting the key parameters mention above, the simplified calculation formula for the coefficient of residual axial compression bearing capacity of the square in square CFDST column after lateral impact is obtained as follows:

In which, \(f(\chi ) = 0.28\chi + 0.58\); \(f(\lambda ) = - 0.0025\lambda + 0.75\); \(f(E_{{\text{k}}} ) = - 0.0078E_{{\text{k}}} + 0.812\);

\(f(f_{{\text{c}}} ) = - 0.0018f_{{\text{c}}} + 0.77\); \(f(f_{{\text{y}}} ) = 0.0007f_{{\text{y}}} + 0.44\). The parametric ranges of: χ is 0.3–0.7, λ is 21.06–42.12, fc is 30–70 MPa, fy is 280–420 MPa, and Ek is 0 ~ 15.93 kJ.

The comparison between the calculated values using Eq. (19), the results of finite element simulation, and the experimental results is shown in Fig. 13. The relative error is less than 10%. Thus, it can be seen that Eq. (19) has a good predictive effect on the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the square in square CFDST column after lateral impact. For square in square CFDST columns subjected to lateral impact, the proposed Eq. (19) can conveniently provide the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the columns according to their properties and the impact energy imposed on them. It has important application value for judging whether the columns can continue to bear loads.

Conclusions

Through numerical simulation, this research analyzes the residual axial compression bearing capacity of square in square CFDST column after lateral impact, and preliminarily draws the following conclusions:

-

(1)

Compared with the un-impacted column, the vertical load–axial displacement curves of the square in square CFDST column after lateral impact roughly go through three stages: the ascending stage, the peaking stage, and the declining stage. With the increase of impact energy, the residual axial compression bearing capacity is significantly reduced, and the ductility is remarkably improved.

-

(2)

Under lateral impact load, the square in square CFDST columns generally exhibit a flexural failure mode. Local indentation occurs at the impact location, and buckling also appears at the bottom of the fixed support section. Three plastic hinges emerge near the impact position and the two fixed supports. After impact, under vertical compression, its failure mode is mainly instability failure, with severe local bulging occurring at the mid-span impact location and the two ends of the support. The longitudinal stress of the concrete mid-span cross-section is mainly in compression throughout the process.

-

(3)

Within the ranges of the parameters studied in this research, the coefficient of residual axial compression bearing capacity decreases with the increase of impact energy, slenderness ratio, and concrete strength, and increases significantly with the increase of steel strength. Reducing the slenderness ratio of the columns or increasing the steel strength can effectively improve the residual axial compression bearing capacity of the column after lateral impact.

-

(4)

A simplified calculation formula for the coefficient of residual axial compression bearing capacity of square in square CFDST columns after lateral impact, which is applicable to impact-resistant design, is proposed with the parametric ranges. This formula provides the residual axial compression bearing capacity of square in square CFDST columns according to their properties and the impact energy imposed on them.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request. The corresponding author should be contacted if someone wants to request the data from this study.

References

Wang, F., Young, B. & Gardner, L. Testing and numerical modelling of circular CFDST cross-sections with stainless steel outer tubes in bending. Eng. Struct. 247(15), 113170 (2021).

Yang, Y., Fu, F., Bie, X. & Dai, X. Axial compressive behaviour of CFDST stub columns with large void ratio. J. Constr. Steel Res. 186(11), 106892 (2021).

Lama, L., Zhou, F. & Bhatt, N. R. Structural performance and design of stainless steel SHS-concrete-carbon steel CHS double-skin stub columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 190(03), 107155 (2022).

Zhang, D. et al. Cyclic behavior and ultimate bearing capacity of circular concrete-filled double skin steel tube members subjected to combined compression and torsion. Thin-Walled Struct. 186(05), 110707 (2023).

Ayough, P., Wang, Y., Zeng, W., Hassanein, M. F. & Elchalakani, M. Numerical investigation and design of concrete-filled double square steel tube columns under axial compression. J. Constr. Steel Res. 212(01), 108277 (2024).

Ayough, P., Ramli Sulong, N. H. & Ibrahim, Z. Analysis and review of concrete-filled double skin steel tubes under compression. Thin-Wall. Struct. 148(03), 106495 (2020).

Elchalakani, M., Ayough, P. & Yang, B. Single Skin and Double Skin Concrete Filled Tubular Structures: Analysis and Design (Elsevier Science, 2022).

Wan, Y., Zhu, L., Fang, H., Liu, W. & Mao, Y. Experimental testing and numerical simulations of ship impact on axially loaded reinforced concrete piers. Int. J. Impact Eng 125, 246–262 (2018).

Jiang, L. et al. Protection performance of a novel anti-collision guardrail with recycled foamed concrete under vehicle collision. Eng. Struct. 305, 117795 (2024).

Wang, H., Lv, N., Lu, Z., Wang, H. & Zong, Q. Experimental study on mechanical properties and breakage of high temperature carbon fiber-bar reinforced concrete under impact load. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 20566 (2024).

Pan, S. & Guo, J. Numerical study on dynamic responses and residual axial bearing capacity of square CFDST columns under lateral impact. J. Constr. Steel Res. 213, 108427 (2023).

Guo, J., Jiang, G., Wu, Z., He, A. & Cai, J. Numerical investigation on the dynamic responses and failure criterion of rc beam under impact. Front. Mater. 9(03), 851301 (2022).

Aya Mohsen, H., Mohamed, A., Fikry Abdo, S., Nabil, M. & Mohamed, G. Experimental and analytical study on axial behaviour of square corrugated concrete filled single and double skin tube stub columns. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 1961 (2025).

Chen, Q., Li, J. & Wang, Q. Experimental study on compression-torsion mechanical properties of concrete filled double skin steel tubes columns with square set square sections. Build. Sci. 37(05), 99–107 (2021) (in Chinese).

Wang, J., Zhong, L., Guo, L., Pan, X. & Lu, J. Pseudo-dynamic test analysis on blind bolted joints between square CFDST columns and steel beams. Chin. Civ. Eng. J. 52(09), 1–11 (2019) (in Chinese).

Shi, Y., Xian, W., Wang, R. & Wang, W. Experimental study on circular-in-square concrete filled double-skin steel tubular (CFDST) composite components under lateral impact. China Civ. Eng. J. 52(12), 11–21 (2019) (in China).

Wang, R., Han, L. H., Zhao, X. L. & Rasmussen, K. J. R. Experimental behavior of concrete filled double steel tubular (CFDST) members under low velocity drop weight impact. Thin-Wall. Struct. 97(9), 279–295 (2015).

Wang, R., Han, L. H., Zhao, X. L. & Rasmussen, K. J. R. Analytical behavior of concrete filled double steel tubular (CFDST) members under lateral impact. Thin-Wall. Struct. 101(4), 129–140 (2016).

Aghdamy, S., Thambiratnam, D. P., Dhanasekar, M. & Saiedi, S. Effects of structure-related parameters on the response of concrete-filled double-skin steel tube columns to lateral impact. Thin-Wall. Struct. 108(11), 351–368 (2016).

Aghdamy, S., Thambiratnam, D. P. & Dhanasekar, M. Experimental investigation on lateral impact response of concrete-filled double-skin tube columns using horizontal-impact-testing system. Exp. Mech. 56(3), 1133–1153 (2016).

Zhao, H., Wang, R., Hou, C. C. & Lam, D. Performance of circular CFDST members with external stainless steel tube under transverse impact loading. Thin-Wall. Struct. 145(12), 106380 (2019).

An, G. Q., Zhao, H., Wang, R. & Li, T. Y. Calculation method for impact resistance of circular concrete-filled double-skin tubular columns with external stainless steel tube. Eng. Mech. 38(6), 227–236 (2021) (in China).

Yan, Q. et al. Residual bearing capacity of concrete-filled double-skin steel tube K-joints after lateral impact. J. Constr. Steel Res. 213, 108424 (2023).

China Architecture & Building Press, T/CCES7—2020, Technical specification for hollow sandwich concrete-filled steel tube structure. (China Architecture & Building Press, 2020). (in Chinese).

Han, L. H. Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular Structures-Theory and Application (Science Press, 2016). (in Chinese)

Cowper, G. R., & Symonds, P. S. Strain-hardening and strain-rate effects in the impact loading of cantilever beams. Small Bus. Econ. (1957).

Hou, C. Study on Performance of Circular Concrete-Filled Steel Tubular (CFST) Members Under Low Velocity Transverse Impact (Tsinghua University, 2012). (in Chinese)

American Concrete Institute, ACI committee 318(ACI 318), Building code requirement for structural concrete and commentary (2005).

Dassault. ABAQUS theory guide. SIMULIA (2021).

Huang, H., Han, L. H., Tao, Z. & Zhao, X. L. Analytical behaviour of concrete-filled double skin steel tubular (CFDST) stub columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 66(4), 542–555 (2010).

Han, L. H., Yao, G. H. & Tao, Z. Performance of concrete-filled thin-walled steel tubes under pure torsion. Thin-Wall. Struct. 45(1), 24–36 (2007).

Comite EURO, CEB-FIP Model Code 1990: Design Code, Comite EURO (1993).

Tao, Z., Uy, B., Han, L. H. & Wang, Z. B. Analysis and design of concrete-filled stiffened thin-walled steel tubular columns under axial compression. Thin-Wall. Struct. 47(12), 1544–1556 (2009).

Yang, X., Yang, H. & Zhang, S. Transverse impact behavior of high-strength concrete filled normal-/high-strength square steel tube columns. Int. J. Impact Eng 139(5), 103512 (2021).

Tao, Z., Han, L. H. & Zhao, X. L. Behaviour of concrete-filled double skin (CHS inner and CHS outer) steel tubular stub columns and beam-columns. J. Constr. Steel Res. 60(8), 1129–1158 (2004).

Han, L. H., Tao, Z., Huang, H. & Zhao, X. L. Concrete-filled double skin (SHS outer and CHS inner) steel tubular beam-columns. Thin-Wall. Struct. 42(9), 1329–1355 (2004).

Cong, S. P., Peng, M., Wang, J. S. & Cong, W. Experimental research on axial compression performance of square double skin steel tube short columns filled with concrete. China Sciencepaper. 14(10), 1085–1089 (2019) (in Chinese).

Wang, F. Y., Yong, B. & Gardner, L. CFDST sections with square stainless steel outer tubes under axial compression: Experimental investigation, numerical modelling and design. Eng. Struct. 207(3), 110189 (2020).

Mi, Y. Study on Residual Bearing Capacity of Ultra-high Performance Concrete-Filled Steel Tubes After Lateral Impact Loading (Tianjin Chengjian University, 2020) (in Chinese).

Guo, J., Pan, S. & Fu, S. Study on the vertical residual bearing behaviors of circular concrete-filled double-skin steel tubular long columns after lateral impact. Eng. Mech. 1–13 (2023). (in Chinese).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by Fujian Province Natural Sciences, 2023J011103.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.G.: Conceptualization, methodology, project administration, performed writing, funding acquisition. P.L.: Resources, funding acquisition. S.P.: Investigation, formal analysis,visualization. M.C.: Writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, J., Li, P., Pan, S. et al. Numerical simulation on residual axial compression bearing capacity of square in square CFDST columns after lateral impact. Sci Rep 15, 24042 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09485-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09485-y