Abstract

Uganda is consistently one of the highest burden countries for mother-to-child transmission of HIV (MTCT). This study assessed Uganda’s progress toward elimination of MTCT and factors associated with MTCT. Mother-infant pairs (MIP) were recruited at immunization clinics at randomly sampled public and private health facilities in Uganda during 2017–2019. Using a multistage sampling method, a nationally representative sample of MIP aged 4–12 weeks were recruited and followed longitudinally for 18 months or until the infant acquired HIV. Early MTCT was defined as an infant with confirmed HIV infection at study enrollment and was calculated using logistic regression to estimate adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for associated factors. Poisson regression was used to estimate incidence rate and incidence rate ratio (IRR) for infants acquiring HIV at any time during the study after enrollment (late MTCT) and associated factors. Early MTCT was 2.2% (95% CI: 1.3–3.6) and late MTCT rate was 5.2 per 1000 person-years (95% CI: 2.5–10.9). In the adjusted model, only detectable maternal HIV viral load (≥ 1,000 copies/mL) was significantly associated with early MTCT (aOR: 6.8, 95% CI: 2.3–19.9). Similarly, ever having a detectable viral load (at any visit) was significantly associated with late MTCT (IRR: 6.2, 95% CI: 1.2–31.7). Uganda’s program has made large strides to eliminate MTCT. Identifying and addressing elevated maternal HIV viral load, especially during pregnancy and the early breastfeeding period could further reduce the number of new childhood infections in Uganda.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV continues to be a challenge to achieving HIV epidemic control. Without intervention, the risk of an infant acquiring HIV is 25–45%, with risk of transmission during pregnancy, birth, and breastfeeding being 5–10%, 10–20%, and 5–20%, respectively1. Maternal antiretroviral therapy (ART) can prevent MTCT2. In 2021, an estimated 160,000 infants worldwide were born with or acquired HIV in the first 18 months postpartum3. The primary reasons for MTCT are new HIV infections in mothers, mothers not receiving ART, mothers discontinuing ART, and mothers on ART with viral load non-suppression (> 1,000 copies/mL)4. The UNAIDS 2030 goals and the WHO Triple Elimination Initiative set a MTCT rate benchmark of less than 5%5.

In Uganda, the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) program started in 20026, after the HIVNET 012 trial found nevirapine could prevent MTCT7. Over time, HIV testing and provision of ART for eligible pregnant and postpartum women were decentralized to all facilities offering antenatal, delivery, and postpartum services including both public and private health facilities. In 2013, Option B+, which expanded ART to all pregnant and breastfeeding women with HIV regardless of CD4 count, was rolled out in Uganda8. By 2016, UNAIDS reported that Uganda reduced HIV infections among children by 86% since 2009 and provided ART access to 95% of women living with HIV to prevent MTCT9. Despite progress, Uganda is ranked among the countries with the highest burden of MTCT with an estimated 6,000 infants born with or acquiring HIV after birth10,11.

To systematically investigate the impact of the Uganda national PMTCT program, the National PMTCT Impact Evaluation Study was conducted to assess the program’s performance and identify gaps in PMTCT services. The survey enrolled mother-infant pairs at enrollment and prospectively followed them from 18 months. The purpose of this analysis was to assess early and late MTCT for women living with HIV in the Uganda PMTCT program and identify factors associated with MTCT.

Methods

Sampling frame

The facility sampling frame included all private and public facilities that provide immunization services across all regions of the country. Sampling utilized the 2015 infant first DPT vaccination coverage. Infant DPT coverage in Uganda is high (> 98% nationally in 2015). First and second DPT are scheduled at 6 and 14 weeks postpartum which aligns with national guidelines for early infant HIV testing making it a useful proxy for a nationally representative sample12. Facilities with < 360 first DPT visits reported during July 2014–June 2015, representing 7% of total first DPT, were excluded from the facility sampling frame to ensure adequate recruitment with available resources. Included facilities had ≥ 360 first DPT visits and were stratified into four categories by volume of reported visits during July 2014–June 2015: low (360–566 visits), medium (567–853 visits), high (854–1343 visits), and highest (≥ 1,344 visits). The resultant sampling frame had 2,611 public and private facilities (low = 650; medium = 656; high = 652; highest = 653). Based on a desired precision of 1.0 and available resources, we randomly selected 5.7% of all facilities within each stratum for each of the 12 regions serviced by MOH regional referral hospitals (Arua, Kampala, Fort Portal, Gulu, Hoima, Jinja, Lira, Masaka, Mbale, Mbarara, Moroto and Soroti) using the random without replacement approach. A total of 152 facilities were selected (low = 37; medium = 39; high = 31; and highest = 45).

Study design

A mixed-methods cross-sectional study was done. During September 2017–March 2018, infants aged 4–12 weeks and their biological mothers (mothers) or non-biological caregivers (caregivers) receiving routine health care at selected facilities were screened. Trained research assistants obtained written informed consent from mother or caregiver before enrolment. Mother/caregiver-infant pairs were excluded if the infant or mother was severely ill, the caregiver was aged < 18 years, or the mother or caregiver did not consent to infant HIV testing. Mothers and caregivers were interviewed to collect demographic and clinical characteristics (e.g., maternal age, ART status, ANC attendance, maternal viral load test results). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Confidentiality of mother-infant information was ensured and all research assistants signed non-disclosure agreements.

For infants accompanied by their mothers, maternal HIV infection was either confirmed by documented receipt of ART (e.g., ANC card, mother’s medical record, infant’s health card) or positive maternal HIV antibody testing following the Uganda MoH national testing algorithm12. Viral load testing was performed for biological mothers with HIV infection. For infants accompanied by a caregiver, maternal HIV infection was confirmed by testing the infant for HIV-1/2 antibodies using heel stick on dried blood sample (DBS) cards.

HIV status for all HIV exposed infants was determined using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Infants identified with HIV were linked to HIV ART care services and were not included in prospective follow up.

All eligible mother-infant pairs (MIP) were asked to return one month after the enrollment visit to receive test results a subset of returning mothers were enrolled for longitudinal follow-up. For longitudinal follow-up, all mothers living with HIV and their HIV negative infants were consented to participate in the 18-months post-partum prospective follow-up (cohort I). After a mother living with HIV and her infant were enrolled, the next five mothers without HIV and their infants at the facility were recruited (cohort II) for prospective follow-up. Among the five recruited mothers, the first four mothers could be of any age, but the fifth mother was aged 15–24 years to provide an adequate sample of adolescent girls and young women.

MIPs had up to five follow-up visits at 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 months postpartum. A ± 6 weeks’ allowance for follow-up visits. Interviews were conducted at each visit to collect information, including infant feeding status, immunization, illnesses or hospitalizations, antenatal and postnatal care services, malaria infection, and interpersonal/intimate partner violence. For mothers living with HIV, additional information was collected on receipt and adherence to infant HIV prophylaxis and maternal ART.

All infants were assessed for HIV at follow-up visits. For infants aged < 18 months, HIV infection was assessed by PCR testing; for infants aged ≥ 18 months, HIV infection was identified through on-site rapid antibody testing. Infants identified with HIV infection were linked to HIV ART care and exited from the study. In addition, mothers living with HIV had maternal viral load testing at the 6- and 12-month follow-up visits. At each visit, mothers living without HIV were screened for new HIV infection using on-site rapid antibody testing, following the MoH algorithm12. If during any visit the mother was newly identified to have HIV, the mother and her infant received the same care as pairs in cohort I.

For infants brought to follow-up visits by a caregiver, only interview questions pertaining to the infant were administered. HIV testing was only conducted if the mother provided prior written informed consent, and results were released only to mothers. If the mother was deceased, results were released to the primary caregiver, and the infant was exited from the study.

Laboratory testing

Tests were performed at the Central Public Health Laboratory in Kampala. Infants of mothers with HIV were tested for presence of HIV RNA by PCR using COBAS AmpliPrep/TaqMan HIV-1 Qualitative assay, version 2.0 (Roche Diagnostics, Branchburg, New Jersey) utilizing infant dried blood samples (iDBS) on Guthrie cards. All first positive or indeterminate results were confirmed by a second PCR test (Amplicor HIV-1 DNA, version 1.5, Roche Diagnostics). For maternal viral load measurement, maternal dried blood spots (mDBS) on Guthrie cards were tested using the Abbott real-time 1.0 ml HIV RNA DBS version 2.00 protocol. DBS samples were transported to the Central Public Health Laboratory within 2 weeks of collection. Left over iDBS and mDBS were stored at −80℃ at Central Public Health Laboratory after testing. Viral load non-suppression was defined as results ≥ 1,000 copies/mL.

Data analysis

Only MIP with infant HIV test results available in cohort I at enrollment were included in this analysis; caregiver-infant pairs and pairs where the mother acquired HIV after enrollment were excluded. To correct for unequal probabilities of selection, a sampling weight was constructed using the reciprocal of a health facility’s probability of selection and adjusting for non-response rate. Weighted early and late MTCT and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were estimated.

We used multiple imputation by chained equation (MICE) for missing data values as our working dataset had multiple variables with missing values. Initially, all missing values were filled in by simple random sampling with replacement from the observed values. The first variable with missing values, x1 say, was regressed on all other variables x2, …, xk, restricted to individuals with the observed x1. Missing values in x1 were replaced by simulated draws from the corresponding posterior predictive distribution of x1.

Early MTCT was calculated as the number of infants identified with HIV infection over the total number of infants tested (e.g., PCR) at enrollment. We used multiple imputation by chained equation (MICE) for missing data values. MICE utilizes a separate condition distribution for each imputed variable and replaces the missing value with a set of plausible values that represent the uncertainty about the value to impute. The level of missingness for each imputed variable was < 20% (0.3 − 16.1%) and all were categorical variables. These included age of the mother, number of pregnancies, birthplace, whether mother was on HAART during pregnancy, nevirapine use after birth and viral suppression. Bivariate analysis was performed and variables with a p-value ≤ 0.2 were included in multivariate logistic regression. Logistic regression was used to obtain odds ration using the 20 multiply imputed data sets that were created. Confidence intervals were calculated using the STATA proportions command.

Late MTCT was calculated as the number of infants identified with HIV infection at follow-up visits (failures) divided by the person-years of observation. Bivariate analysis was performed to identify factors with p-values ≤ 0.2 for the regression model. For late MTCT, Poisson regression was used for the calculation of incidence rate and incidence rate ratios, respectively.

All analyses accounted for stratification and weighting explicitly by using the svyset function. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA® version 15 (Stata Corp LP, Texas, USA).

Ethical approvals

This study was reviewed and approved by the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI) (FWA No.00001354) and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (FWA No. 00001293) IRBs (see 45 C.F.R. part 46.114; 21 C.F.R. part 56.114).

Results

Characteristics at enrollment

In total, 12,627 MIP were screened for inclusion and 12,075 (95.6%) were enrolled (Table 1). A total of 1,290 MIP were enrolled in cohort I (mothers living with HIV) and 1,177 MIP were included in this analysis (Table 2). The mean maternal age was 24.9 years (range = 15–51 years). Only 24.8% of mothers reported having a secondary education or higher. Almost all mothers (97.3%) attended antenatal care, with the largest proportion (43.9%) receiving care at health center II (HCII). ART information was available for 987 mothers of which 98.7% were on ART (Table 3). The maternal viral load suppression rate at enrollment for those with viral load test results was 87.1% (914/1,049).

The mean age of infants at enrollment was 8.0 weeks (range = 3.7–12.4 weeks) and 49.5% were male infants. The majority (85.1%) of infants received nevirapine prophylaxis and 88.5% were exclusively breastfed at enrollment.

Early mother-to-child transmission of HIV

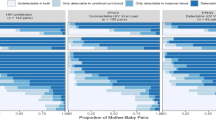

Twenty-five infants were identified with HIV infection at enrollment, corresponding to an early MTCT of 2.2% (95% CI: 1.3–3.6). Maternal ANC attendance during pregnancy (OR: 0.2, 95% CI: 0.1–0.8) was associated with decreased risk of early MTCT. Delivering the infant in a private facility (OR: 3.2, 95% CI: 1.2–8.6) or at home (OR: 3.5, 95% CI: 1.1–10.6) increased the likelihood of early MTCT compared to delivering in a public facility. Detectable maternal viral load at enrollment (OR: 10.1, 95% CI: 3.9–26.1), and infant not receiving nevirapine prophylaxis (OR: 5.7, 95% CI: 2.5–13.0) were also associated with early MTCT. Mother on ART (OR: 0.1, 95% CI: 0.0-0.4) reduced the likelihood of early MTCT.

In the adjusted model, only having a detectable viral load (≥ 1,000 copies/mL) at enrollment significantly increased the odds of early MTCT (aOR:6.8, 95% CI: 2.3–19.9).

Late mother-to-child transmission of HIV

Of the 1,177 MIP enrolled at baseline, a total of 1,066 were enrolled for prospective follow-up and had infant testing data available. A total of seven infants (0.7%; 95% CI: 0.3–1.5%) were identified with HIV infection during prospective follow-up. The late MTCT rate was 5.2 per 1000 person-years (95% CI: 2.5–10.9). Due to the small number of infants that acquired HIV during prospective follow-up, analysis of factors was limited (Table 4). In Poisson regression, only a detectable maternal viral load at any time (enrollment, 6-month follow up visit, and/or 12-month follow-up visit) was significantly associated with late MTCT (IRR: 6.2, 95% CI: 1.2–31.7) (Table 5).

Discussion

This was the first national evaluation of the PMTCT program in Uganda. The early MTCT of 2.2% and late MTCT of 0.7% demonstrate that Uganda’s PMTCT program has made large strides in reducing MTCT of HIV and achieving well below the WHO target of 5%5. In this evaluation, the proportion observed for early MTCT was higher than the late MTCT rate. Continued engagement in maternal and child healthcare during pregnancy and the early breastfeeding period and efforts to keep mothers in care until breastfeeding cessation could be critical areas of focus to achieve elimination of MTCT of HIV.

Overall, maternal viral load non-suppression was the only risk factor associated with both early and late MTCT. These findings are consistent with literature documenting the relationship between non-suppressed viral load and MTCT13,14,15. Of note, rates of maternal ART use in this study were high, but approximately 1 in 10 mothers were not virally suppressed at some point during the study. This suggests that viral non-suppression is likely due to maternal non-adherence to ART. However, it should be noted that during the study time period, pregnant and breastfeeding women had limited access to optimal ART regimens containing dolutegravir12. These findings highlight the need for optimizing regimens among women of reproductive age, and consistent viral load testing and prompt response to elevated viral load. Rates of viral load coverage remain suboptimal for pregnant women and even lower for women newly diagnosed in pregnancy, who are more likely to have non-suppressed viral load16,17. With such a small number of mothers with non-suppressed viral load, a more intensive, patient-centered focus on optimization of ART regimen, identification of barriers to ART adherence, and age appropriate enhanced adherence counseling could be considered to close the final gap for elimination of MTCT18.

Of note, infant non-receipt of nevirapine was only significantly associated with early MTCT in bivariate analysis, but not in the adjusted model19,20. Non-adherences to ARVs, including infant prophylaxis, remains a challenge in preventing MTCT especially for mothers new to ART, younger mothers, and those with no available viral load test results19,20.

In this analysis, the majority of new childhood infections were identified in infants who acquired HIV during pregnancy or the early breastfeeding period. These findings differ from the 2023 UNAIDS Spectrum estimates that suggest that almost half of new child infections occur during the breastfeeding period11. These differences could be related to the population included for this survey. Women who acquired HIV during prospective follow-up were not included in this analysis, but can contribute significantly to new child infections11. It should also be noted that because MIP were recruited when the infant was 4–12 weeks old, infections acquired very early during the breastfeeding period may have been miscategorized as early MTCT. Lastly, MIPs in the study were followed to 18 months, so mothers may have received additional support to continue adhering to ART through the breastfeeding period.

There were at least four limitations in this study. First, the total number of infants identified with HIV at enrollment and the prospective studies was low, limiting the regression analysis and inclusion of infant feeding method as a factor in the adjusted model and resulting in wide confidence intervals. Second, the study was not able to actively follow-up MIP that transferred to areas outside of the 152 study sites. As a result, transient MIP may have been lost to follow-up. Third, MIP were recruited from child immunization clinics, thus creating selection bias in the sample. While immunization rates in Uganda are high, MIP not engaging in early childhood care or engaging outside the enrollment age would not have been screened for participation in the study. Lastly, test results for some infants and maternal viral load tests were not available due to sample quality, missing results, and data entry errors. However, because of high coverage of DPT 1 nationally, the sample is likely to be nationally representative.

Overall, the findings of this study highlight that a focused, country-wide effort to provide PMTCT programming has reduced MTCT of HIV in areas of high- and low- prevalence for all age groups. While rates of ART linkage have continued to rise, this may not be sufficient to achieve elimination of MTCT. An increased focus on addressing viral load non-suppression, including regular viral load testing, throughout pregnancy and breastfeeding could further reduce the burden of new childhood infections in Uganda.

Implications to policy and practices

These results highlight the critical factor played by maternal viral load in MTCT and the importance of optimizing regimens among all women of reproductive age to improve chances of being virally suppressed at conception and throughout pregnancy. Additionally, more optimal algorithm for PMTCT clients that reduces the time between viral load testing to three months could facilitate prompter action and prevent MTCT. Further, urgent improvement of clinical management of viral non-suppressers through intensive adherence interventions and/or timely and appropriate switching of non-suppressed mothers to optimal regimens would further reduce MTCT.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request and can be disclosed when required.

References

WHO. PMTCT Strategic Vision 2010–2015: Preventing Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV to Reach The UNGASS and Millenium Development Goals. (2010).

Siegfried, N., van der Merwe, L., Brocklehurst, P. & Sint, T. T. Antiretrovirals for reducing the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. Cd003510 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003510.pub3 (2011).

UNAIDS & Global HIV & AIDS satistics - Fact sheet. (2023).

UNAIDS. UPDATE: One hundred and fifty thousand preventable new HIV infections among children in 2020, (2021). https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2022/january/20220131_preventable-new-HIV-infections-among-children

Committee, E. G. V. A. Global Guidance on Criteria and Process for Validation: Elimination of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV, Syphilis, and Hepatitis B Virus. (2021).

Namara-Lugolobi, E. et al. Twenty years of prevention of mother to child HIV transmission: research to implementation at a National referral hospital in Uganda. Afr. Health Sci. 22, 22–33 (2022).

Marseille, E. et al. Cost effectiveness of single-dose nevirapine regimen for mothers and babies to decrease vertical HIV-1 transmission in sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet. /09/04/ 1999;354(9181):803–809. (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(99)80009-9

Ministry of Health U. Annual Health Sector Performance Report 2012/13. (2013).

UNAIDS. Global Plan country fact sheets. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/campaigns/globalplan/factsheets

Start Free, S., Free, A. I. D. S. & Free Final report on 2020 targets. July. (2021). https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2021/start-free-stay-free-aids-free-final-report-on-2020-targets

2014 & Uganda HIV and AIDS Country Progress Report (2015).

DREAMS Partnership. U.S. Department of State. Accessed March 1. (2023). https://www.state.gov/pepfar-dreams-partnership/

Guidance on HIV Prevention Among Adolescent Girls and Young Women. (2016).

Consolidated Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of HIV in Uganda (2016).

Dirlikov, E. et al. Scale-Up of HIV antiretroviral therapy and Estimation of averted infections and HIV-Related Deaths - Uganda, 2004–2022. MMWR Morb Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 72, 90–94. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7204a2 (2023).

Mandelbrot, L. et al. No perinatal HIV-1 transmission from women with effective antiretroviral therapy starting before conception. Clin. Infect. Dis. 61, 1715–1725. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/civ578 (2015).

Myer, L. et al. HIV viraemia and mother-to-child transmission risk after antiretroviral therapy initiation in pregnancy in cape town, South Africa. HIV Med. 18, 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.12397 (2017).

Woldesenbet, S. A. et al. Coverage of maternal viral load monitoring during pregnancy in South africa: results from the 2019 National antenatal HIV Sentinel survey. HIV Med. 22, 805–815. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.13126 (2021).

Alemu, A., Molla, W., Yinges, K. & Mihret, M. S. Determinants of HIV infection among children born to HIV positive mothers on prevention of mother to child transmission program at referral hospitals in West amhara, ethiopia; case control study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 48, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-022-01220-x (2022).

Napyo, A. et al. Barriers and enablers of adherence to infant nevirapine prophylaxis against HIV 1 transmission among 6-week-old HIV exposed infants: A prospective cohort study in Northern Uganda. PLoS One. 15, e0240529. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240529 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Rakai Health Sciences Program (RHSP) data collectors, Steve Okokwu, Laurie Gulaid, Doreen Agasha, Jackie Calnan, Daniel Idipo, Philip Kasibante, Ivan Lukabwe, Alfred Lutaaya, Christina Mwangi, Godfrey Kigozi, Gertrude Nakigozi, Bernadette Ng’eno, Tamara Nyombi, Margaret Okwero, Vamsi Vasireddy, Rakai Health Sciences Program (RHSP) data collectors, the health care workers at participating study sites, and study participants and their families. We also acknowledge the invaluable contributions of Dr. Joshua Musinguzi (Deceased), former Program Manager, Ministry of Health, AIDS Control Programme to this research.

Funding

This project and publication has been supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) under the terms of 1U2GGH00817-4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LN, PN, FN, FM, DO, DT, MA, HA, EB, and TL contributed to conceptualization and design of the study and research question. JK, IS, and JO contributed to the acquisition of data. TM conducted the statistical analysis with contributions from FM, DT, SS, and RN. LN and AD were primarily responsible for drafting of the manuscript. All authors made substantial contributions to interpretation of the data and review of the manuscript. All authors provided final approval of the manuscript to be published and agreed to be held accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding agencies.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nabitaka, L.K., Delaney, A., Namukanja, P.M. et al. An impact evaluation of the national prevention of mother to child HIV transmission program and MTCT associated factors in Uganda 2017–2019. Sci Rep 15, 24402 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09511-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09511-z