Abstract

DNA profiling has been an important tool in human forensic for almost four decades, revolutionising criminal investigations. In recent years, it has also been utilised in timber identification and geographical traceability of stolen logs, with notable increase in forensic DNA analysis related to forest crimes, driven by the growing concerns over illegal logging and forest conservation. In this study, DNA profile database for a tropical timber species, Koompassia malaccensis was established, with a total of 1465 samples from 56 locations across Malaysia genotyped using nine short tandem repeat (STR) markers. Based on the results of cluster analyses, the STR database was partitioned into WM (West Malaysia), EM (East Malaysia) and PS (Peat Swamp) Database. Thereafter, each regional/ecological database was characterised for forensic parameters and allele frequencies. Due to weak population differentiation, the percentage of individuals correctly assigned to the population of origin was low. However, the assignment tests to the region of origin were highly accurate (mean = 99.6%). The STR database is robust and has been used to assist the enforcement agencies in the investigation of forest crimes involving K. malaccensis. A case study is presented to demonstrate its application for individual identification in forensic context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Koompassia malaccensis Maingay ex Benth. (Leguminosae) is one of the major commercial timber species traded in South-East Asia, distributed in Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, and Borneo1. It is a very large tree, can grow up to 55 m in height, and up to 200 cm in diameter. In Peninsular Malaysia, K. malaccensis is commonly known as kempas, whereas in Sabah and Sarawak, it is called impas and menggris, respectively. It is found in lowland, hill, peat and fresh water swamp forests, usually below 150 m, although its occurrence up to 610 m has been reported1. Despite being listed as Least Concern (LC) under the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List, version 3.12, K. malaccensis is a protected tree species in the states of Sabah3 and Sarawak4.

The Standard Malaysian Name for its timber is Kempas, a medium hardwood with a density of 770–1120 kg/m3 air dry. Kempas is a monospecific timber, as it only refers to K. malaccensis, unlike most timber trade names, which typically encompass a genus or a group of related species. Kempas wood is suitable for interior as well as exterior usage5. It has a fine, interlocked grain pattern, making it very popular for furniture, flooring, and cabinetry. K. malaccensis is potentially vulnerable to illegal logging because of its widespread distribution and commercial value. Among the medium hardwoods traded domestically in Malaysia, Kempas sawn timber is the second most expensive, after Keruing, which is the timber trade name for Dipterocarpus species. In 2024, the price per cubic metre under General Market Specification (GMS) was approximately USD$513 for Kempas, compared to Keruing (USD$700)6.

Illegal logging refers to all activities related to harvesting, processing and trading of timber that violate national and sub-national laws7, including logging without a license. It not only causes deforestation, but also leads to significant revenue loss for the governments of timber-producing countries. To curb illegal logging and deforestation, a growing number of consumer countries have enacted legislation to prohibit trade in illegal timber, such as the U.S. Lacey Act, the European Union Timber Regulation, and the more recent Korea Act on the Sustainable Use of Timbers and Japan Clean Wood Act. Several positive impacts have been realized in the United States (US) and European Union (EU) markets. The volumes of illegal wood-based products imported by the US fell by one-third in 2013, compared to their peak in 2006, and volumes halved over the same period in three EU countries8.

Validating timber species and origin are the key to documenting and demonstrating compliance with timber laws and regulations. Over the past decade, new tools and resources have been developed to support due diligence throughout the supply chains9, including timber tracking based on structural characteristics (wood anatomy), chemical (direct analysis in real-time time-of-flight mass spectrometry (DART-TOFMS) and near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS)), and genetic methods (DNA barcoding and profiling). These tools vary in their scalability (identification of genus, species, individual and geographical origin), applicability in the field (screening on the front-line or as diagnostic laboratory methods), and cost effectiveness (processing speed, equipment and expertise required)10.

The “Best Practice Guide for Forensic Timber Identification” published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) provides information on appropriate procedures and methods involved in the entire investigation process, from the crime scene to the court room, to ensure consistent and quality results across jurisdictions11. Meanwhile, World Forest ID focuses on building a comprehensive reference database of geo-referenced plant samples, in partnership with regulatory and enforcement agencies worldwide, to enable species identification and tracing of harvest location12, facilitating verification of the products’ claimed geographic origins.

There is promising progress in the development of scientific verification technologies for identifying species and geographic origin based on the priority tree species listed by the Global Timber Tracking Network (GTTN)13,14. Based on the 322 taxa (36 genera, 286 species) species priority list, the status of technology for species identification has been assessed: reference data exist for all taxa using wood anatomy, followed by 86% using DNA barcoding loci, 41% using DART TOFMS spectra, and 6% using NIRS spectra14. In comparison, the progress in identifying geographic origin is still lacking, with data only exist for 24% of taxa, mainly using genetic approaches (23%)14. This disparity highlights the need for more studies on determining the geographical origin of timber, especially in the Asia, Pacific, and Oceania region, in addition to Central and South America14.

In Malaysia, the National Forestry Act 1984 (Amendment 2022) serves as the current legal framework to provide for the administration, management and conservation of forests, protecting against illegal logging and deforestation. With the aim of supporting national effort to combat illegal logging, the Forest Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM) has developed comprehensive short tandem repeat (STR) DNA profiling databases for several important tropical timber species, including Neobalanocarpus heimii15, Gonystylus bancanus16, Rubroshorea platyclados17, R. leprosula18, Intsia palembanica19 and Aquilaria malaccensis20. These databases have been applied to assist forest enforcement authorities in forest crime investigations, providing forensic evidence to convict illegal loggers. In this paper, we report the establishment of an STR database of K. malaccensis in Malaysia, and present a case study on its application as an investigative tool in forensic context.

Results

Population structure

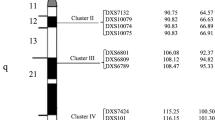

The Bayesian-based STRUCTURE analysis divided the 56 populations of K. malaccensis into two genetic clusters. i.e. Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 (Fig. 1A). All the 37 populations grouped under Cluster 1 are from West Malaysia, while Cluster 2 consists of all the 13 populations from East Malaysia plus the seven peat swamp populations from West Malaysia. Upon further STRUCTURE analysis, Cluster 2 was sub-divided into Cluster 2a (all populations from East Malaysia except Maludam) and Cluster 2b (all peat swamp populations in this study) (Fig. 1B). The eight peat swamp populations are SKarangB, RMusa, KLangat, Pekan, Nenasi, Resak, AHitam, and Maludam, with Maludam being the single peat swamp population sampled from East Malaysia. Notably, the result from cluster analysis based on genetic distance (DA) concurs with this finding, whereby the UPGMA dendrogram displays the same grouping pattern (Cluster 1, 2a, 2b), with bootstrap ≥ 90% (Fig. 2).

Bayesian clustering results. (A) The 56 populations of Koompassia malaccensis from Malaysia were partitioned into two clusters: Cluster 1 and 2 (K = 2). Cluster 1 consists of 37 populations from West Malaysia (WM); Cluster 2 consists of East Malaysia (EM) populations and Peat Swamp (PS) populations. (B) Cluster 2 was further subdivided into: Cluster 2a (all EM populations except Maludam) and 2b (all PS populations) (K = 2). (C) Map of Malaysia showing the sampling locations and the population structure inferred from STRUCTURE analysis; PS populations are indicated in red font.

Individual identification database

Correspondingly, the STR database for K. malaccensis was partitioned according to the aforementioned three regions (geographical/ecological), and designated as WM (West Malaysia), EM (East Malaysia) and PS (Peat Swamp) Database. The forensic parameters for the nine STR loci by region are given in Table 1. The allele frequencies of each STR locus by region are provided in Table S1, S2 and S3. In total, 170, 162 and 82 alleles were observed in WM, EM and PS regions, respectively. The power of discrimination (PD) for each STR locus ranged from 0.6905 to 0.9762 (WM), 0.6509 to 0.9708 (EM) and 0.3402 to 0.9076 (PS). In West Malaysia, 56% of the STR loci were found to be departed from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) after Bonferroni corrections, whereas 44% and 22% deviation from HWE were observed in East Malaysia and Peat Swamp, respectively. Nevertheless, these results reflect the reality in natural populations, whether in humans, animals, or plants; whereby the assumptions of completely random mating and zero migration, necessary for HWE, are unlikely to be met21,22,23.

Mean self-assignment, i.e. the proportion of individuals correctly assigned to the population of origin, was 36.7%, ranging from 0% (Klau, Som) to 96.6% (Maludam) (Table S4). However, at the regional level, the mean successful assignment rate of an individual to the region of origin was very high (WM 99.3%, EM 100.0% and PS 99.6%).

Conservativeness of the database

The minimum allele frequency was adjusted for alleles falling below the thresholds of 0.0026 (WM), 0.0093 (EM) and 0.0100 (PS) (Table S1, S2 and S3). The coancestry coefficient (θ) for EM (0.0898) was the highest, followed by PS (0.0528) and WM (0.0254) (Table 2). The inbreeding coefficient (f) for EM was also the highest (f = 0.1122), compared with PS (f = 0.0763) and WM (f = 0.0249). All the θ and f values were significantly greater than zero, demonstrated by the 95% confidence intervals not overlapping with zero. Both the θ and f values were used to evaluate the conservativeness of each database by testing the cognate database (Porigin) against the regional database (Pcombined). The database was not totally conservative at the calculated θ value. Hence, in order to ensure conservativeness, the value of θ was adjusted accordingly for WM (from 0.0254 to 0.3772), EM (from 0.0898 to 0.4285) and PS (from 0.0528 to 0.2909) (Fig. S1).

Discussion

Despite the larger area of East Malaysia (60% of the total land area of Malaysia) compared with West Malaysia (Peninsular Malaysia), about 80% of the samples of this study were collected from Peninsular Malaysia (43 populations, n = 1168), with only four populations from Sabah and nine from Sarawak (n = 297). One of the key reasons for the smaller overall sample size in East Malaysia is due to the fact that the expenditure incurred for sampling trips to East Malaysia is significantly higher compared to within Peninsular Malaysia. Besides flights, ferries and land transportation, boats were employed to reach some of the remote populations like Batang Ai, Amang and Putai, as well as Maludam (the only peat swamp forest from the Borneo in this study). Moreover, there were actually a few more sampling locations covered in Sabah – Madai, Bukit Tawau and Siaunggau Forest Reserves and Sarawak - Sampadi, Gunung Singai, Similajau, Bukit Lima Nature Reserve and Klingkang Range, but because of the small sample size (average four per location), they were excluded from the study. A few other forest reserves were also surveyed but we did not manage to find K. malaccensis (Bukit Gemuk, Crocker Range and Rafflessia from Sabah; Gading and Gunung Santubung from Sarawak).

Koompassia malaccensis from peat swamp areas made up 14% of the population samples (n = 250). The genetic diversity level of PS is remarkably lower among the regions, with the mean number of alleles per locus observed of only nine, compared to 19 (WM) and 18 (EM). The coancestry coefficient (θ) for EM (0.0898) was the highest, followed by PS (0.0528) and WM (0.0254) (Table 2). In other words, only 8.98%, 5.28% and 2.54% of the genetic variability was distributed among populations within EM, PS and WM, respectively.

Based on the allele frequency distributions of the candidate populations, it is possible to test whether an individual with a certain STR profile is likely to originate from a given population through assignment test38. The average self-assignment, i.e. the average proportion of individuals correctly assigned to the population of origin, was 36.7% (Table S4). Among the 36 populations in WM, only minority of populations have correct assignment above 50% (PSelatan 63.9%, Pelagat 59.1% and Bbandi 52.4%). Comparatively, in the case for EM and PS, 75% of the populations from the respective regions have the self-assignment rate above 50%. This is due to the weaker population differentiation in WM (θ = 0.0254), compared to EM (θ = 0.0898) and PS (θ = 0.0528). On the contrary, at the regional level, the successful assignment rate of individuals to the region of origin was very high, with an average of 99.6% (West Malaysia 99.3%, East Malaysia 100.0% and Peat Swamp 99.6%).

The STR analysis revealed different genotypes possessed by K. malaccensis populations in West Malaysia compared to East Malaysia. For example, at locus Kma082, alleles 271, 273, 275, 277, 281, 285 and 292 could only be found in West Malaysia. The STRUCTURE analysis showed that K. malaccensis populations from peat swamp forests and populations in East Malaysia were clustered together as Cluster 2. This finding is congruent with the result of the STRUCTURE analysis, which also yielded two clusters with the same groupings, i.e., Cluster 1 (WM) and Cluster 2 (EM & PS). In the subsequent sub-structure analysis, two genetic clusters were further delineated for K. malaccensis from East Malaysia (Cluster 2a; excluding Maludam) and those from the peat swamp forests (Cluster 2b), using both approaches. East Malaysia populations exhibit some unique genotypes compared to other populations of peat swamp habitat. For example, at locus Kma147, alleles with size lesser than 331 bp can only be found in EM.

Locus Kma127 exhibits the highest PD, an average of 0.9515 across the three regions. On the contrary, Kma172a exhibited the least PD in each region, average PD = 0.5605. A total of three regional STR individual identification databases were developed according to the respective genetic clusters, namely WM, EM and PS Database.

In the past, the enforcement authorities relied solely on wood anatomy and morphometric evidences to link the suspected illegal loggers to the crime scene. This conventional approach has its limitations, in that species identification is often only feasible to the genus level, or to the group of timber species of a particular trade name, whereas the seized logs and stumps were matched through the morphological characteristics, such as log/stump-diameter and shape. While species identification via DNA barcoding could solve the former, DNA profile databases will facilitate in tackling the latter. As demonstrated in the following case study, the STR database developed in this study is useful for individual identification and geographic traceability of K. malaccensis wood in the context of forensic application.

Case study

Herein, we demonstrate how the STR database of K. malaccensis was applied to assist an investigation officer of an enforcement agency (Department of Wildlife and National Parks Peninsular Malaysia), and successfully solved an illegal logging case. This case study involved felling of valuable timber trees within one of the gazetted wildlife reserves in Pahang state, Peninsular Malaysia. Based on morphological traits and wood anatomy, K. malaccensis was identified as one of the timber species among the seized logs. We received a request from the investigation officer to assist in carrying out DNA analysis.

An extensive forested area adjacent to the stack of felled logs was surveyed to find as many K. malaccensis stumps as possible. Sampling was carried out with the help of the local indigenous people, who are familiar with the forest. Following FRIM’s Standard Operating Procedure on “Forensic DNA Testing for Plant Species Identification and Timber Tracking”, SOP 1: “Specimen Collection in the Field”25, a total of 170 seized K. malaccensis logs (assigned as L1 – L170) and 22 potential stumps (assigned as S1 – S22) were collected, 5–10 bark discs were obtained for each sample using a hollow steel punch of 2 cm diameter. After every sample, the hollow punch was wiped with 70% ethanol to avoid contamination. It was significantly more challenging and arduous to locate and sample the K. malaccensis stumps scattered throughout the vast forest than it was sampling from the suspected logs from a single locality.

Subsequent DNA extraction followed by forensic DNA testing were conducted in FRIM Genetics Laboratory. Using the SOP 2: “DNA Isolation and Purification from Wood”, the total DNA of the samples were extracted and purified. The purified DNA samples were then genotyped for nine STR loci using SOP 4: “STR Genotyping for Population and Individual Identification”. Of all the logs sampled, 65 unique 9-loci STR profiles were acquired, ranging from 1 to 4 logs per profile. Results showed that the STR profile of logs L75, L79 and L80 matches that of stump S12 (171/188, 156/162, 230/230, 255/255, 271/271, 342/344, 258/264, 148/150 and 278/278 at STR loci Kma011a to Kma057, please refer Table 1 for the sequence of loci genotyped). The rest of the STR profiles of the remaining logs did not match those of the other 21 stumps.

A random match probability between the log and the potential stumps can be established by using the frequency database. Random match probability (RMP) is the probability of a match between an unknown timber and its potential origin stump. It is the reciprocal of profile frequency (1/profile frequency), i.e. the estimated frequency at which a particular STR profile is present in a population21. By considering both population sub-structuring and inbreeding coefficient, the coancestry coefficient (θ) value was adjusted to increase the profile frequency, while reducing the weight of the DNA evidence against a defendant in a court proceeding24. In this particular case study, WM database was applied for the calculation of RMP because the wildlife reserve is located in Peninsular Malaysia, and it is not a peat swamp forest. The estimated RMP between logs L75, L79 and L80 and stump S12 was 3.2981 × 10−10.

In order to ascertain that the STR profiles of the stump and logs did not match by chance in a court proceeding, statistical methods such as likelihood ratios (LR) are necessary to extrapolate the evidentiary value of this match21. LR is a comparison of the probabilities of the evidence under two hypotheses. The first hypothesis represents the position of the prosecution that logs L75, L79 and L80 originated from stump S12. Conversely, the second hypothesis represents the position of the defendant that the STR profiles matched by chance and logs L75, L79 and L80 did not originate from stump S12. The LR equals the hypothesis of the prosecution, Hp (numerator) divided by the hypothesis of the defendant, Hd (denominator) [LR = Hp/Hd]. While the prosecution hypothesis that logs L75, L79 and L80 originated from stump S12 (Hp) equals to one, assuming 100% probability; the RMP of the defendant’s claim that logs L75, L79 and L80 originated from an unknown stump can be calculated as aforementioned.

In short, LR is the inverse of the estimated profile frequency, in this case, 1/(3.2981 × 10−10) = 3.0320 × 109, thus providing an evidence with extremely strong support from the proposition that logs L75, L79 and L80 originated from stump S12. Although only three suspected logs were traced to one of stumps located in the wildlife reserve, it is enough to prove that forest offense has been committed by the suspect.

To test the efficiency of using the STR database for geographic traceability, the 9-locus STR profiles of these 22 K. malaccensis stumps were subjected to assignment test, and all these individuals were assigned to West Malaysia [non-peat-swamp forests], with mean percentage of 99.9996%.

Conclusion

We report on the development of a DNA profiling database for an important timber species, K. malaccensis in Malaysia, using STR markers. The STR database is robust and has been validated for specificity and accuracy, enabling the calculation of RMP and LR in the event an unknown log is traced to a potential stump of origin, using appropriate database (WM, EM or PS). In cases where the sample source is unknown, it is possible to trace the geographic/ecological origin(s) of K. malaccensis samples with high accuracy (99.6%) via assignment test. And thereafter utilise the corresponding regional database if there is a need for individual identification.

Combined with other timber reference databases, STR databases for the indigenous timber species will serve as an impetus for the uptake of DNA technology in forestry forensic. The technology adoption rate depends largely on effective dissemination of information to the forest managers and relevant enforcement agencies. Besides raising awareness on the availability of DNA-based timber identification system, active engagement, technology transfer and cooperation between researchers and the relevant stakeholders are crucial to leverage DNA technology in the fight against illegal logging. In addition, given that timber STR database is species-specific, it is imperative to establishing more databases for other timber species of economic importance, to curb illegal logging activities.

Having said that, acquisition of quality DNA from the alleged stolen wood sample is a prerequisite for forensic DNA analysis. In the present case of K. malaccensis, we were able to extract intact DNA from the suspected logs despite short term exposure to outdoor weather. Moreover, it is relatively much easier to obtain DNA samples from living stumps. Given other scenarios, where seized wood or timber might have been dried or processed, extracting sufficient and quality DNA for analysis could be challenging. For such difficult wood samples, the yield of DNA could be increased by enhancing the DNA extraction method, while the use of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) could be a solution to overcome the limitation of degraded DNA materials, which impedes the acquisition of full STR profile. However, establishing SNP databases for timber species of interest using NGS approach would require the reference genome sequence.

Methods

Sample collection and DNA extraction

In total, we have collected 1,465 K. malaccensis samples from 56 forested areas, with an average sample size of 26 per population (Table 3). The sampling locations spanned throughout the East and West Malaysia (Fig. 1). Of the 56 populations, eight were of peat swamp habitat (seven from Peninsular Malaysia, one from Sarawak). Ramli Ponyoh from FRIM assisted in species identification during sampling. A voucher specimen from Mukah Hill has been deposited in FRIM herbarium -A1686 (KEP). For the samples from Peninsular Malaysia, approximately 5 g of leaf or cambium tissue per sample was weighed and wrapped in aluminium foil and kept in liquid nitrogen after processing during sampling trips, prior to DNA extraction. Whereas those from Sabah and Sarawak, the leaf or inner bark samples were collected, weighed and kept in silica gel during transportation to the laboratory. As for the sampling of logs and stumps in the case study, the cambium samples were collected using a hollow steel punch.

The total DNA was extracted using the cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method26 with modification. The frozen leaf or cambium samples (~ 5 g each) were cryogenically ground with SPEX® SamplePrep 6875 Freezer/Mill (New Jersey, USA) for 1 min. Each grindate was immediately transferred into a 50 mL Nunc tube (Falcon) with 20 mL of prewarmed (60 °C) CTAB extraction buffer (20 mM Na2EDTA, 100 mM TrisHCI pH 8.0, 1.4 M NaCI, 1% [w/v] PVP-40, 2% [w/v] CTAB, 0.2% [v/v] 2-mercapthethanol) and incubated at 60 °C for 30–60 min. Subsequently, 20 ml of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) was added and mixed gently for 15 min. After centrifuging at 3000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature, the aqueous layer was transferred to a new tube. Two-thirds volume of cold (− 20 °C) propan-2-ol was added and mixed gently to precipitate the nucleic acids. Precipitated DNA was dissolved in TE (10 mM TrisHCI pH 8.0, I mM Na2EDTA).

Short tandem repeat genotyping

Genotyping of the 1,465 K. malaccensis samples was carried out using nine STR loci27, in two multiplex sets (Table S5). These STR markers are reproducible and robust in allele size calling, they have been stringently selected from among the 24 markers developed27, excluding those with suspected presence of null allele and allele dop-out. The forward primers were fluorescently labelled either with 6-FAM (Kma011a, Kma096, Kma109, Kma172a and Kma147), HEX (Kma127 and Kma057) or NED (Kma082 and Kma026). The multiplex-PCR consists of 1x Type-it Multiplex PCR Master Mix (Qiagen), 0.4 µM for each primer and 10 ng of template DNA. PCR amplification was performed by using the programme: activation step at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of a denaturation step at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 52–57 °C for 90 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s; and a final extension at 60 °C for 30 min. The PCR products were electrophoresed along with GeneScan 400HD ROX Standard as the internal size standard on an ABI 3130xl capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Genotyping was carried out using GeneMarker v2.6.4 software (Soft Genetics LLC, Pennsylvania, USA). The reproducibility of all STR markers was tested by comparing the genotypes from five independent PCR amplifications on one individual28.

Data analysis

A model-based clustering analysis, employing a Bayesian algorithm in STRUCTURE v2.3.4 was used to infer the genetic structure of K. malaccensis in Malaysia (56 populations), and substructuring of the populations in East Malaysia and peat swamp (20 populations). In each STRUCTURE analysis, 10 independent runs were performed by setting the K values ranging from 1 to 10, a burn-in length of 250,000 and followed by 500,000 Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC)29 steps. We applied models of admixture with sampling locations included as prior population information. Correlated allele frequencies were applied for 10 repetitions. The most likely number of genetic clusters was chosen based on the Delta K statistic30 via the analysis using the online version of STRUCTURE SELECTOR31. After the best K value was selected, a graphical representation of the results from the 10 independent runs of STRUCTURE analyses was generated using CLUMPAK32. In addition, genetic relatedness among populations was inferred from the UPGMA dendrogram based on chord distance, DA, generated by using the program POPTREE233. The relative strengths of the nodes were determined based on 1000 bootstrap replicates.

Establishment and characterization of STR database

An STR database for individual identification of K. malaccensis was established following the approach by Tnah et al.15 After the completion of STR genotyping for all the K. malaccensis samples, based on the results from STRUCTURE and cluster analyses, the STR database was divided according to three regions, designated as West Malaysia (WM), East Malaysia (EM) and Peat Swamp (PS) Database, corresponding to Cluster 1 (947 individuals), 2a (268 individuals) and 2b (250 individuals). The genetic diversity parameters of these STR loci for each region were assessed by calculating the number of alleles per locus (A), observed (Ho) and expected heterozygosity (He), using the program Genetic Data Analysis (GDA) v1.134. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) for each population was tested, with p value for departure from HWE adjusted by Bonferroni correction35.

Forensic parameters for each regional database, viz., polymorphic information content (PIC), matching probability (MP) and power of discrimination (PD) were calculated using FORSTAT36. The coancestry coefficient (θ) and inbreeding coefficient (f) for each region were estimated using GDA37, with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Self-assignment tests were used to evaluate the proportion of correctly assigned individuals to population and regional levels, using GENECLASS238. The first level was at the designated population. The second level was at the genetic cluster revealed through the clustering analyses, corresponding to the three regions (WM, EM & PS).

The allele frequency for each locus was computed using the program Microsatellite Toolkit39. With the assumption that K. malaccensis is a diploid, a conservative minimum allele frequency of 5/2n was applied to ensure that an allele has been sampled sufficiently to be used reliably in the statistical tests. While n is the number of individuals sampled from a population, 2n is the number of chromosomes counted because autosomes are in pairs due to the inheritance of one allele each from one’s maternal and paternal parent. The profile frequency was calculated by multiplying the frequency of each locus, across all the nine STR loci based on the subpopulation-cum-inbreeding model40.

The conservativeness of each database was estimated by calculating the full profile frequency of each individual using the genotype frequencies derived from the cognate database (Porigin), which is the population database, against profile frequency of each individual using genotype frequencies derived from the combined database (Pcombined), i.e., the corresponding regional database. The relative difference (d) between the databases was defined as d = log10 (Porigin/Pcombined); d value is negative when Porigin < Pcombined, indicating that the database is conservative24. In order to ensure that each regional database is conservative, a series of θ adjustments were applied to recalculate Pcombined until all individuals within the respective region present a negative d value.

Plant collection declaration

We declare that all our experimental research and field sampling of plant materials comply with local, national or international guidelines and legislation.

Data availability

The sequence information of the STR primer pairs has been deposited at NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under the accession no. DQ356305-DQ356328.

References

Whitmore, T. C. Tree flora of Malaya: a manual for foresters. Malay. For. Records No 26. 1, 471 (1972).

IUCN. (2023).

Sabah. Wildlife Conservation Enactment 1997 (No. 6 of 1997). (1997).

Sarawak, L. Wildlife Protection Ordinance, 1998, Sarawak, Malaysia. (1998).

Gan, K. S. & Lim, S. C. Common Commercial Timbers of Peninsular Malaysia (Forest Research Institute Malaysia, 2004).

Malaysia Timber Industry Board (MTIB). Maskayu Januari 2025, Vol 1 (MTIB, 2025).

Kleinschmit, D., Mansourian, S., Wildburger, C. & Purret, A. Illegal Logging and Related Timber trade-dimensions, Drivers, Impacts and Responses. A Global Scientific Rapid Response Assessment Report Vol. 35 (International Union of Forestry Research Organizations, IUFRO Secretariat, 2016).

Hoare, A. Tackling Illegal Logging and the Related Trade: What Progress and Where Next? (Chatham House, 2015).

Schmitz, N. et al. Overview of Current Practices in Data Analysis for Wood Identification. A Guide for the Different Timber Tracking Methods (Global Timber Tracking Network, GTTN secretariat, European Forest Institute and Thunen Institute, 2020).

Dormontt, E. E. et al. Forensic timber identification: it’s time to integrate disciplines to combat illegal logging. Biol. Conserv. 191, 790–798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2015.06.038 (2015).

UNODC. Best Practice Guide for Forensic Timber Identification (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2016).

Gasson, P. E. et al. Addressing the need for standardized wood reference collections to support authentication analysis technologies; a way forward for checking the origin and identity of traded timber. Plants People Planet. 3, 130–141 (2021). WorldForestID.

Cramm, M. & Van Brusselen, J. List of priority tree species for the development of reference data for determination of tree species and their geographic origin. Update of the GTTN priority tree species list of 2013. Global Timber Tracking Network, European Forest Institute, Joensuu. https://globaltimbertrackingnetwork.org/portfolios/priority-tree-species/ (2019).

Low, M. C. et al. Tracing the world’s timber: the status of scientific verification technologies for species and origin identification. IAWA J. 44, 63–84 (2023).

Tnah, L. H., Lee, S. L., Ng, K. K. S., Faridah, Q. Z. & Faridah-Hanum, I. Forensic DNA profiling of tropical timber species in Peninsular Malaysia. For. Ecol. Manage. 259, 1436–1446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2010.01.017 (2010).

Ng, K. K. S. et al. Forensic timber identification: a case study of a CITES listed species, Gonystylus bancanus (Thymelaeaceae). Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 23, 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2016.05.002 (2016).

Ng, C. H. et al. Geographic origin and individual assignment of Shorea platyclados (Dipterocarpaceae) for forensic identification. PLoS One. 12, e0176158. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176158 (2017).

Ng, C. H. et al. DNA databases of an important tropical timber tree species Shorea leprosula (Dipterocarpaceae) for forensic timber identification. Sci. Rep. 12, 9546. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-13697-x (2022).

Ng, C. H. et al. A geographical traceability system for Merbau (Intsia Palembanica Miq.), an important timber species from Peninsular Malaysia. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 44 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2019.102188 (2020).

Lee, S. L. et al. DNA databases of a CITES listed species Aquilaria malaccensis (Thymelaeaceae) as the tracking tools for forensic identification and chain of custody certification. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 57 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2021.102658 (2022).

Butler, J. M. Forensic DNA Typing: Biology, Technology, and Genetics of STR Markers (Elsevier Science, 2005).

Waits, L. P., Luikart, G. & Taberlet, P. Estimating the probability of identity among genotypes in natural populations: cautions and guidelines. Mol. Ecol. 10, 249–256 (2001).

Triggs, C. M. & Buckleton, J. S. Logical implications of applying the principles of population genetics to the interpretation of DNA profiling evidence. Forensic Sci. Int. 128, 108–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0379-0738(02)00168-8 (2002).

Gill, P., Foreman, L., Buckleton, J. S., Triggs, C. M. & Allen, H. A comparison of adjustment methods to test the robustness of an STR DNA database comprised of 24 European populations. Forensic Sci. Int. 131, 184–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0379-0738(02)00423-1 (2003).

Lee, S. L. et al. FRIM’s Standard Operating Procedure on Forensic DNA Testing for Plant Species Identification and Timber Tracking. Version 1.5 (Forest Research Institute Malaysia, 2020).

Murray, M. & Thompson, W. F. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 8, 4321–4325 (1980).

Lee, C. T. et al. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite markers in Koompassia malaccensis (Leguminosae), an important tropical timber species. Mol. Ecol. Notes. 6, 1198–1201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-8286.2006.01490.x (2006).

Dawnay, N. et al. A forensic STR profiling system for the Eurasian badger: A framework for developing profiling systems for wildlife species. Forensic Sci. Int. Genet. 2, 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2007.08.006 (2008).

Pritchard, J. K., Stephens, M. & Donnelly, P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959. https://doi.org/10.1093/genetics/155.2.945 (2000).

Evanno, G., Regnaut, S. & Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software SRTUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 14, 2611–2620. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x (2005).

Li, Y. L. & Liu, J. X. StructureSelector A web-based software to select and visualize the optimal number of clusters using multiple methods. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 18, 176–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12719 (2018).

Kopelman, N. M., Mayzel, J., Jakobsson, M., Rosenberg, N. A. & Mayrose, I. Clumpak: a program for identifying clustering modes and packaging population structure inferences across K. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 15, 1179–1191. https://doi.org/10.1111/1755-0998.12387 (2015).

Takezaki, N., Nei, M. & Tamura, K. POPTREEW: web version of POPTREE for constructing population trees from allele frequency data and computing some other quantities. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31, 1622–1624. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msu093 (2014).

Lewis, P. O. & Zaykin, D. Genetic Data Analysis (GDA): computer program for the analysis of allelic data. Version 1.1, University of Connecticut, Storrs. http://phylogeny.uconn.edu/software/ (2001).

Rice, W. R. Analyzing tables of statistical tests. Evolution 43, 223–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1989.tb04220.x (1989).

Ristow, P. G. & D’Amato, M. E. Forensic statistics analysis toolbox (FORSTAT): A streamlined workflow for forensic statistics. Forensic Sci. International: Genet. Supplement Ser. 6, e52–e54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigss.2017.09.006 (2017).

Weir, B. S. & Cockerham, C. C. Estimating F statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution 38, 1358–1370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.1984.tb05657.x (1984).

Piry, S. et al. GENECLASS2: a software for genetic assignment and first-generation migrant detection. J. Hered. 95, 536–539. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhered/esh074 (2004).

Park, S. Excel Microsatellite Toolkit. Version 3.1. 1. Animal Genomics Lab website (University College, Dublin, Ireland, 2008).

Ayres, K. L. & Overall, A. D. J. Allowing for within-subpopulation inbreeding in forensic match probabilities. Forensic Sci. Int. 103, 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0379-0738(99)00087-0 (1999).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security Malaysia [then Ministry of Agriculture and Agro-based Industries] (Project No. 05-03-10-SF1033). We thank Ramli P, Ghazali J, Yahya M, Yasri B, Rosman I, Rantai J, Jumian J, Chang AB, Sawai P, Andy S, Dino J, Mariam D, Nurul Hudaini M, Sharifah T and late Suryani CS for field and technical assistance. We are grateful to the Forest Department of Peninsular Malaysia and respective State Forest Departments, Sarawak Forestry Corporation as well as Sabah Forestry Department for their cooperation and permission to collect samples for research. We are also indebted to Rimbunan Hijau, Golden Cash Harvest Sdn. Bhd. and Jaya Tiasa Holdings for their hospitality in hosting us at their logging camps during our sampling trips in Sarawak [(Mukah Hill Camp (RH), Putai Camp and Nanga Amang Camp (GCH)].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

“S.L.L and C.T.L. conceptualized the work and study design; C.T.L. and S.L.L. planned and implemented the research. All authors were involved in sample collection. B.D and E. K were in charge of the logistic arrangements during field trips in Sarawak and Sabah. C.T.L., C.H.N., L.H.T, K.K.S.N., S.L.L. contributed to the experimental work and data analysis. C.H.N. and C.T.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.”

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, C.T., Ng, C.H., Tnah, L.H. et al. DNA profile database of Koompassia malaccensis in Malaysia and its application in forensic investigation. Sci Rep 15, 24504 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09566-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09566-y