Abstract

Tn916, the most typical conjugative transposon that contains the tetM resistance gene, has been identified in various genomes. This study examined the recognized Tn916 (with an identity of > 90%) and Tn916 other family members (with identities between 60 and 90%) in all currently known complete genome and chromosome sequences, naming them Tn916.1 to Tn916.9. Tn916 and other members of this family have similar structures: AT-rich inverted repeats (IRs), with the boundaries being AT-rich stem‒loop structures; the coupling sequences in the middle, often 5 bp AT-rich regions, with the conserved base is the first base A or the last base T; the stem sequence from the host, which often matches or complements part of the IR (4–5 bp). Most Tn916 family members have ABC transporter gene clusters as resistance markers, and Tn916.9 has vancomycin resistance genes. Tn916 and other members of this family are more frequently integrated into genomes that have low GC% values. Our study elucidates the structural characteristics of the regions flanking Tn916 and other members of this family, laying a molecular foundation for further determining their deletion and integration mechanisms and aiding in controlling the spread of such antibiotic resistance in these conjugative transposons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mobile genetic elements, such as prophages, integrated plasmids, genomic islands (GIs), and transposons, are acquired and spread through horizontal gene transfer and constitute a significant part of bacterial genomes1. GIs frequently have direct repeats (DRs) at their borders. Conjugative transposons (CTns), a subclass of mobile genomic islands2are transferred from donors to recipients through the conjugation mechanism, and the horizontal transfer of CTns is a major facilitator of the maintenance and evolution of bacterial chromosomes, as well as the spread of antibiotic resistance genes3,4. The boundaries of transposons are composed of DRs and inverted repeats (IRs) adjacent to the DRs. IRs are key structural elements located at the termini of transposons and are typically involved in recognition and cleavage by transposases. Understanding their functional roles is critical for elucidating the mechanisms of transposition.

Tn916, the first characterized CTn, was initially found in several strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae5 and later in Enterococcus faecalis DS16. This CTn encodes a tetracycline resistance gene (tetM) and exhibits autonomous transposition and conjugative transfer6. Tn916 is an 18 kb CTn with a wide host range7 that is able to integrate into plasmids or different sites of host genomes (via multiple copies)8. Some copies are inserted by some genetic elements9,10,11 whereas others are contained within other larger mobile GIs12,13,14,15,16.

Tn916 is composed of four functional modules: the recombination, transcriptional regulation, transcriptional regulation auxiliary (tetracycline resistance gene, tetM)17,18 and conjugative transfer modules. The recombination module contains genes for integrase (int) and excisionase (xis), which together facilitate the insertion and excision of the transposon from the host genome2. The transcriptional regulation module regulates the expression of genes within the transposon, ensuring proper timing and levels of gene expression. The auxiliary function module houses tetM, which confers resistance to tetracycline antibiotics and enhances bacterial survival in antibiotic-rich environments17,19,20. The conjugative transfer module contains genes of the type IV secretion system (T4SS) necessary for the transfer of the transposon between bacterial cells through conjugation.

Tn916 is excised from the donor’s insertion site, forming a circular intermediate with approximately 6 bp of unmatched DNA; the donor DNA is reconnected, and the unmatched region is eliminated through DNA replication21. The circular intermediate transfers a single strand into a suitable recipient cell through rolling circle replication and conjugative transfer mechanisms, and the complementary strand is synthesized in both the donor and recipient and then integrated into the genome. Through genomic DNA replication, the heteroduplex DNA of Tn916 is eliminated3,21.

Despite extensive knowledge of the mobility mechanisms of Tn916, a comprehensive analysis of its distribution and structural variations across bacterial genomes is lacking. This study, for the first time, based on the integrase with transposase characteristics of Tn916 in E. faecalis DS16, performed localization analysis of Tn916 and its family in complete genomes and chromosomes sequenced to date and then identified the boundary sequences of these transposons, thereby identifying the key site recognized by the integrase. The modular structures were present in the Tn916 family. The integration sites of Tn916 and its family were marked in the specific strains. This study provides new insights into the mechanism of action of such integrases, improves the efficiency and accuracy of the use of Tn916 and other members of this family as genetic tools, and will be beneficial for exploring effective methods to remove Tn916 and other members of this family from resistant bacteria.

Materials and methods

Selection of strains

We selected bacterial strains from complete genomes and chromosomes that contained integrases that shared an identity of at least 60% with the Tn916 integrase (AAB60030.1) found in Enterococcus faecalis DS16.

Identification and localization of Tn916

-

1)

Initial Screening: The integrase sequence AAB60030.1 was used as a query to perform BLAST searches (default parameters) against all complete and 3/4-complete genomes in the NCBI database. Enzymes with ≥ 90% sequence identity were selected as candidate integrases.

-

2)

Transposon Identification: The canonical Tn916 sequence (U09422.1) was used as a query to perform a BLAST search (with default parameters) against the same genome datasets to identify homologous regions.

-

3)

Boundary Extension and Intra-Species BLAST: For each candidate enzyme-containing strain identified in the initial BLAST results, genomic regions spanning 1,000 bp upstream of the 5’ boundary and 1,000 bp downstream of the 3’ boundary were extracted. These flanking sequences were then subjected to intraspecies BLAST analysis (default parameters) to identify homologous regions within the same bacterial species.

-

4)

Negative Control Criteria: Strains exhibiting a continuous 2,000 bp BLAST alignment with minor gaps (at about 1,000 bp region) were defined as potential negative controls.

-

5)

Refined Alignment: Potential negative controls were prioritized by similarity (highest to lowest). The sequences were reanalyzed via intraspecies BLAST with adjusted scoring parameters (match/mismatch = 1/-2) using the original alignment results. If no overlapping regions were detected with these parameters (match/mismatch = 1/-2), the scoring matrix was further adjusted to (match/mismatch = 2/-3) with all other parameters remaining at their default values.

-

6)

Transposon Delineation: In the candidate strains, the high-identity 2,000 bp region was segmented into two overlapping fragments. The intervening sequence contained transposase, integrase, or recombinase genes. If these conditions were met: DRs were extended bidirectionally from the overlap region (allowing ≤ 3 consecutive mismatches); The range of the transposon was defined as the region from the first base of the upstream DR to the last base of the downstream DR. If the conditions were not met, the next potential negative control was analysed iteratively (returning to step 5 unless all controls were exhausted, then reverting to Step 3).

-

7)

Termination: The localization process concluded after all candidate integrases were processed (steps 3–6).

Localization of the Tn916 family

-

1)

Candidate Selection: Integrases with 60–90% identity to AAB60030.1 (via BLAST, default parameters) were classified as Tn916 family candidates.

-

2)

Representative Enzyme Identification: The candidate with closest to 90% identity was designated the representative enzyme of the Tn916 family subclass. If ≥ 3 enzymes with ≥ 90% identity (from Step 1) were found in complete genomes, these enzymes and the representative were assigned to the subclass. Otherwise, a new representative was selected iteratively.

-

3)

Preliminary Boundary Mapping: For one enzyme per subclass (≥ 90% identity to the representative), 400 bp upstream/downstream sequences were used as queries for intraspecies genomic BLAST searches.

-

4)

Negative Control Screening: Strains with BLAST alignments of < 400 bp (indicating upstream truncation for lower boundaries or downstream truncation for upper boundaries) were flagged as potential negative controls.

-

5)

Extended Boundary Analysis: High-similarity potential controls were prioritized. Their BLAST alignments were expanded by 1 kb upstream/downstream and re-analyzed with modified scores (match/mismatch = 1/-2). If no overlapping regions were detected with these parameters (match/mismatch = 1/-2), the scoring matrix was further adjusted to (match/mismatch = 2/-3) with all other parameters remaining at their default values.

-

6)

Subclass Validation: Valid Tn916 family members required: A segmented 2,000 bp high-identity region with overlapping fragments; The presence of a transposase/integrase/recombinase gene in the intervening sequence; A DR extension (≤ 3 consecutive mismatches allowed) to define the range of the transposon (upstream DR start → downstream DR end).Unqualified strains triggered iterative reanalysis (step 5 → step 3 if all controls failed).

-

7)

Iterative Classification: This iterative process (Steps 3–6) was repeated for the remaining candidates until all the enzymes were categorized.

-

8)

Data compilation: The representative enzymes and their host strains are catalogued in Table S1.

Phylogenetic classification and nomenclature of the Tn916 family

We selected one integrase from each integration site of each strain within every transposon family. Multiple sequence alignment was conducted using MAFFT version 7 (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/index.html) with default parameters. The aligned sequences were then used for subsequent analysis. Alignment trimming was performed using TrimAl v1.4 with the -automated1 option, which automatically determines the most suitable trimming strategy based on the statistical properties of the alignment, including gap distribution, residue similarity, and information content. This approach provides an optimal balance between alignment quality and information retention for accurate phylogenetic inference. A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was reconstructed using IQ-TREE 3 based on the input alignment file “fx tree.fasta.” (Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15607807). The best-fit substitution model was automatically selected using ModelFinder(JTT + G4). Branch support was evaluated with 1,000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates and 1,000 SH-aLRT (approximate likelihood ratio test) replicates. BCZ37821.1 was designated as the outgroup. The analysis was conducted using automatic thread allocation and a fixed random seed to ensure computational reproducibility.The resulting phylogenetic tree was subsequently visualized and annotated using Evolview v222 (http://www.evolgenius.info/evolview/) and all taxa were labeled in a clockwise direction. Subsequently, phylogenetic cross-validation was conducted using Bayesian inference implemented in MrBayes.

Determination of IRs, flanking stem‒loop structures, and conserved bases of coupling sequences in Tn916 and other members of this family

The 100 bp base sequences on both sides of Tn916 and other members of this family were aligned via ClustalW to identify their upstream IR start base and downstream IR end base. Nonconsecutive single- or double-base mismatches were permitted; however, the alignment process was terminated upon the detection of three or more consecutive mismatched bases.

The boundary stem‒loop structures of transposons were determined by identifying complementary pairing between the upstream IR and the upstream sequence located 5–6 bp away from the first nucleotide, as well as between the downstream IR and the downstream sequence positioned 5–6 bp away from the terminal nucleotide.

The TA combination proportion in the upstream and downstream stem‒loop structures of Tn916 and other members of this family was calculated as the number of integration sites containing at least one TTTA or TAAA numerator divided by the total number of integration sites identified for the transposon family (denominator). The bases located above the line represent the stem regions of the stem‒loop structures.

Drawing a modular diagram of the Tn916 family CTns

By manually comparing the annotation data in the GenBank gb file of the Tn916 family CTns of the same type but located at different integration sites in the genome, a CTn with the most complete module structure and no foreign gene insertion was selected and used as a representative of the Tn916 family CTns to draw the module diagram.

Spearman correlation analysis of host GC content and ICE density

We calculated integration density (Integration density was calculated as the reciprocal of the average distance between two ICE insertions in kilobases) in strains widely distributed with Tn916 and its family members. Spearman’s rank correlation test was performed using R (R version 4.4.1), with GC content as the independent variable and ICE density as the dependent variable. Correlation coefficients (ρ) and p-values were reported.

Results

Localization, classification and naming of Tn916 and other members of this family in bacterial genomes

A total of 577 Tn916 family transposons were identified, and by using AAB60030.1 as a benchmark, they were found to be integrated into 240 genomic sites, predominantly within Bacillota (Table S2). Among these, 338 Tn916s were integrated at 129 genomic sites across Bacillota (dominant) (most prevalent in Staphylococcus aureus (18.34%) and S. pseudintermedius (13.61%)), Pseudomonadota, and Mycoplasmatota (Table S2-1). There was only one strain with this transposon in both Pseudomonadota and Mycoplasmatota. Haemophilus ducreyi (Pseudomonadota) was a gram-negative bacterium, while the others were gram-positive. One copy was often integrated into genomes, and 21 18 kb Tn916sCd were present in 14 strains, among which 7 strains had 2 copies.

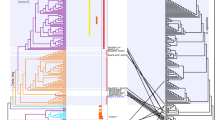

Tn916 classes are site specific. Integrase phylogeny (IQ-TREE3) revealed 9 clustered groups (Tn916.1–Tn916.9, clockwise) (Fig. 1). In this study, we constructed phylogenetic trees using both IQ-TREE and MrBayes, and compared the support values for major clades.The vast majority of clades received consistently high support values (> 98%) across both methods (Fig. S1), indicating a stable and reliable phylogenetic structure. For instance, clades Tn916.2 to Tn916.4 and Tn916.6 to Tn916.8 were supported with values close to or equal to 100 in both IQ-TREE and MrBayes analyses. However, clade Tn916.1 showed a discrepancy, receiving a support value of 100 in IQ-TREE but only 72 in MrBayes, suggesting a level of inconsistency between the two methods for this branch.

Notably, clade Tn916.5 received a support value of 0% in both IQ-TREE and MrBayes, indicating a highly unstable phylogenetic placement. Overall, the phylogenetic topologies inferred by IQ-TREE and MrBayes were highly consistent, with most branches showing strong support, thereby reinforcing confidence in the internal structure of the Tn916 group. The few observed differences point to potential data ambiguities or model sensitivities that warrant further investigation.

Tn916 family transposons exhibit taxon-specific distribution patterns and genomic characteristics across bacterial taxa (Tables S3-2 to S3-10). Within Bacillota and Actinomycetota, Tn916.1 (5–16 kb) and Tn916.2 (12–59 kb) display broad host specificity. Notably, 69 Tn916.1 transposons were integrated into 35 sites, predominantly in Clostridioides difficile (20%) and Enterococcus faecium (51%), with an exceptionally large variant (Tn916.1Bb − JCM7017, 163 kb). Moreover, 76 Tn916.2 transposons occupied 45 sites, primarily in C. difficile. Intraspecies variability was observed in Clostridium innocuum, which harboured 3 Tn916.1 transposons in two strains. A unique immune evasion phenomenon was noted in Amedibacterium intestinale JCM 30884, carrying three ~ 30 kb Tn916.2 copies. Specifically, Tn916.3 (22–46 kb) exclusively targeted C. difficile (Bacillota), with 43 copies across 7 sites (a single copy per strain). All Tn916 family transposons possessed AT-rich DRs at their boundaries.

Identification of inverted repeats for Tn916 and other members of this family

Through ClustalW alignment (Figs. S2-1 to S11-2), the IRs of Tn916 and its family were identified (starting from the 5’ or 3’ end and ending where three consecutive mismatches occurred) (Table 1). However, owing to the lack of data for Tn916.5 and Tn916.6 and the inability to identify their IRs through ClustalW, it is possible that their structures have degraded over time in the genome or that existing methods have not been able to accurately localized these IRs. The IRs of Tn916 and the other seven members of this family are all AT-rich. In Tn916.2, the IRs of the transposons Tn916.2Bb − NRBB49, Tn916.2Ef − E4438−1, and Tn916.2Ci − LCLUMCCI001–3 are inconsistent with those of other transposons at the same integration sites (Figs. S4-1 and S4-2).

Determination of the boundary stem‒loop structures of Tn916 and other members of this family

An analysis of the DRs and adjacent sequences of Tn916 and other members of this family with clearly defined IRs revealed that both upstream and downstream sequences form AT-rich stem‒loop structures. The upstream stem‒loop structure is composed of a sequence from the upstream host genome sequence + a 5 bp (mostly) coupling sequence + the upstream IR, and the downstream stem‒loop structure is formed by the downstream IR + a 5 bp (mostly) coupling sequence + a sequence from the downstream host genome, where in the sequences from the upstream/downstream host genome are reverse complementary to the upstream/downstream IR sequences (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Files). The sequence from the upstream or downstream host genome is identical or complementary to one endpoint of the IR sequence with 4 or 5 bp, with their conserved bases being 5’-X(G/A/T)TTT-3’ (5’-AAAY(C/T/A)-3’) (Fig. 2; Table 1).

Reorganization of conserved bases in the coupling sequences of Tn916 and other members of this family

In the coupling sequences of Tn916 and other members of this family, the first nucleotide is A or the last nucleotide is T, forming combinations of TTTA or TAAA (the underlined part is close to the coupling sequence in the stem structure of the stem‒loop structure) (Fig. 2). The proportions of TA combinations are 100% for both Tn916.3 and Tn916.4, 91.43% (32/35) for Tn916.1, 76.74% (33/43) for Tn916.2, 75.18% (106/141) for Tn916, 71.43% (5/7) for Tn916.7, and 33.33% (3/9) for Tn916.9, whereas Tn916.8 has too few integration sites and does not form the TTTA or TAAA combination. The results revealed that in Tn916, Tn916.1, Tn916.2, Tn916.3, Tn916.4, and Tn916.7, the conserved base in the coupling sequence is the first A or the last T.

Modular structure of the Tn916 family

Most members of the Tn916 family contain four modules, similar to Tn916 (Table S3). The recombination module always contains integrase and excisionase, with the identity of the excisionase proteins exceeding 75% (Fig. 3). The transcription regulation module invariably possesses orf7 (a sigma factor) and orf8 (a potential transcription-regulating, HTH domain-containing protein) (Fig. 3). The auxiliary function module is composed of different antibiotic resistance genes, with Tn916 carrying the tetracycline resistance gene; Tn916.2 is divided into three subtypes according to the auxiliary function module, named Tn916.2①, Tn916.2②, and Tn916.2③, which all carry the ABC transporter gene cluster but with low identity among the modules; and Tn916.3 and Tn916.7 also carry the ABC transporter system gene cluster, conferring multidrug resistance. Prokaryotic ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters are versatile molecular machines with critical roles in bacterial survival, pathogenesis, and antibiotic resistance. The conjugation transfer modules of the Tn916 family vary significantly. Tn916.4 has too few members, and the specific module structure of Tn916.1 cannot be determined because of the large variation in the functional genes of each module structure and some of the auxiliary function modules being absent.

Distribution of Tn916 and other members of this family in chromosomes

Tn916 and other members of this family are primarily distributed within species such as C. difficile, C. innocuum, E. faecalis, E. faecium, S. aureus, S. pseudintermedius, S. agalactiae, S. pneumoniae, S. pyogenes and S. suis. The greatest number of integration sites for Tn916 and other members of this family were identified in C. difficile DSM 27639, E. faecium E7237, E. faecalis JY32, and C. innocuum I46 (CP022722.1). Three Tn916.2, 1 Tn916.1, 1 Tn916.3 and 1 Tn916.7 transposon were integrated in C. difficile DSM 27639, conferring multidrug resistance through various ABC transporter gene clusters. Thirty-eight other integration sites for the Tn916 family also exist in this strain, indicating weaker resistance to the Tn916 family (Fig. S12-a). One Tn916.9 transposon was integrated into E. faecium E7237, conferring vancomycin resistance, and 21 other Tn916 family integration sites were also present in this strain (Fig. S12-b). One Tn916 transposon was integrated into E. faecalis JY32, conferring tetracycline resistance, and 9 other Tn916 family integration sites were also present in this strain (Fig. S12-c). Three Tn916.1 and 2 Tn916.2 transposons were integrated in C. innocuum I46 (CP022722.1), conferring multidrug resistance, and 6 other Tn916 family integration sites were also present in this strain (Fig. S12-d). The genome of the C. difficile DSM 27639 strain has a GC% of 29%, making it a hotspot for the integration of Tn916 family transposons; one Tn916 family transposon can be integrated at approximately every 97 kb. The genomic GC contents of E. faecium E7237, E. faecalis JY32, and C. innocuum I46 (CP022722.1) were 38%, 38%, and 43%, respectively, and one Tn916 family transposon was integrated at approximately every 123 kb, 293 kb, and 406 kb, respectively. We conducted a Spearman rank correlation analysis between GC content (independent variable) and ICE density (dependent variable). The results showed a strong negative correlation trend, with a Spearman correlation coefficient of ρ = -0.949 and a p-value of 0.051.

Discussion

Research status for Tn916 and other members of this family

Our findings revealed that Tn916 is widely distributed across various bacterial species, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies. For example, Tn916 shares high identity with Tn5251, which is found in Streptococcus pneumoniae23. In Bacillus subtilis BS49, multiple copies of Tn916 have been reported24 which aligns with our observation of multiple integration sites in certain strains (Table S2-1). Similarly, in Clostridioides difficile, both single and multiple copies of Tn916 have been identified25. We detected up to two copies of Tn916 in some C. difficile strains (Table S2-1), suggesting variability in transposon integration frequency. Furthermore, our detection of Tn916 in Staphylococcus aureus strains, including two copies in strain ER11236.3 (Table S2-1), expands the known host range of Tn916 and highlights its role in the spread of antibiotic resistance26.

Tn621827 shares high identity with some Tn916.1s, indicating that it belongs to Tn916.1. Tn607328 shares high identity with a 29 kb transposon (Tn916.2Cd − S0352−2) in Tn916.2s. Tn154929 shares 99% identity with a transposon approximately 33.8 kb in size in Tn916.9 (Tn916.9Ef − E7237). Tn387230 shares 99% identity with Tn916Sa − GBS19.

Analysis of the action sites of the integrase in Tn916 and other members of this family

All ten classes of transposons have TA-rich IRs. Past research identified the terminal IRs of Tn916 as 5’-AAAATAG-3’/5’-CTTTGTTT-3’6. This study, by aligning all the Tn916 terminal sequences, ultimately determined that the terminal IRs of Tn916 are 5’-AAAAATAG-3’/5’-CTTTGTTT-3’ (Figs. S2-1 and S2-2), with an additional A at the 5’ end of the upstream IR compared with the sequences from previous studies.

The coupling sequences of most Tn916 family members have the first base A or the last base T as the conserved base, which is predicted to be the key base for the action of this class of integrases (supplementary files). As demonstrated by Caparon et al.31 Tn916 utilizes dual integration/excision mechanisms and deletion mechanisms, with its coupling sequence being 5 bp31 which is consistent with the findings of this study for Tn916 and other members of this family. Anna Rubio-Cosials et al. determined the stem‒loop structure of Tn1549 as 5’-AATTTTATAGCAAAATT-3’, with a 5 bp coupling sequence (5’-ATAGC-3’) and the cleavage site within the stem being T32. This study revealed that the Tn916.9 family has the same IRs as Tn1549, but further experimental evidence is needed to determine whether the conserved A(T) in the coupling sequences plays a role in cleavage.

Among the ten classes of Tns, the integrases in Tn916.2, Tn916.3, and Tn916.4 share greater than 82% identity, and some of the conserved IRs near the coupling sequences are the same (5’-AAAAAC-3’//5’-GTTTTT-3’). Thus, predicting this sequence is a key determinant of the activity range of this class of integrases, whereas the remaining IR sequences play a supporting role.

Modular structure and antibiotic resistance diversity of the Tn916 family

This study revealed that the spread of antibiotic resistance via the Tn916 family is attributed mainly to multidrug resistance conferred by ABC transporter gene clusters, in addition to vancomycin resistance gene clusters. Currently, six families of bacterial efflux pumps, one of which is the ABC family, members of which directly use ATP as a source of energy for transport, have been identified and help in efflux pathways33. All ABC transporter system gene clusters in the Tn916 family are located on the auxiliary function module, suggesting the existence of different mechanisms of multidrug resistance. Tn916.1 contains a rich array of resistance genes. Past research has revealed the presence of the cfr resistance gene in E. faecium27; this study, in Tn916.1, identified not only the cfr resistance gene but also tetM, a bifunctional aminoglycoside N-acetyltransferase, and ABC transporter elements.

The conjugation transfer module, located upstream of the transcription regulation module and auxiliary function module, is essential for intercellular transposition of the Tn916 family. The conjugation transfer modules of members of the Tn916 family vary significantly, but compared with that of Tn916, all of them have the corresponding C40 family peptidases (except for Tn916.7), with lower identity observed in Tn916.9. Except for Tn916.9, Tn916 and other members of this family contain antirestriction proteins, with one antirestriction protein in the three Tn916.2 subtypes and each Tn916.3 sharing approximately 60% and 40% identity with Tn916, respectively, and Tn916.7 containing one antirestriction protein with approximately 40% identity. The three subtypes Tn916, Tn916.2, and Tn916.3 all contain two types of YdcP family proteins, with those in Tn916.3 sharing the highest identity with those in Tn916, 66% and 72%, respectively. A comparison of the conjugation transfer modules among the Tn916 families revealed that the three Tn916.2 subtypes and Tn916.3 all contain adhesin, with identities greater than 90%. Tn916.2② and Tn916.2③ both have an N-acetyltransferase, with an identity of 99%. Tn916.7 and Tn916.9 both have a DNA topoisomerase III family protein, with an identity of 66%.

Integration site diversity of Tn916 and other members of this family

The integration sites of the Tn916 family are often in AT-rich areas. Spearman’s rank correlation analysis showed a high inverse correlation (ρ= − 0.95, p = 0.051). Correlation coefficient (ρ= − 0.95) indicates a very strong negative correlation between GC content and ICE density, p-value (p = 0.0513) is slightly above the commonly used significance threshold of 0.05, suggesting the result is marginally significant in statistical terms, suggesting that integration is favored in more AT-rich genomes. The genomes of all three strains have clusters of integrated Tn916 family members, with the C. difficile DSM 27639 genome having 8 Tn916 family integration sites within the 382 kb-594 kb range and 6 Tn916 family integration sites within the 2,151 kb-2,264 kb range. The E. faecium E7237 genome has 6 Tn916 family integration sites within the 592 kb-727 kb range and 3 Tn916 family integration sites within the 1,370 kb-1,424 kb range. The C. innocuum I46 (CP022722.1) genome has 3 Tn916 family integration sites within the 3,567 kb-3,661 kb range.

Other mobile genetic elements present in Tn916

During conjugative transfer between cellular genomes and transposition within the genome, Tn916 can harbour other transposons. In this study, transposons at the same integration site and with a size of 20.9 kb, such as Tn916Sp − 574, Tn916Sp − ASP0581, and Tn916Sp − Hungary19A6, all harboured an ISL3 transposon with a size of 2.8 kb, with all ISL3 transposon DRs being 5’-TTTTTTTG-3’ (except for the one additional T downstream in Tn916Sp − Hungary19A6). Tn916Sp − PZ900701590 had an ISL3 transposon that was 2.8 kb in size and an approximately 900 bp IS1515 inserted internally. Tn916Sp − HUOH, Tn916Sp − GPSHK21sc2296565, and Tn916Sp − KK0381 all harboured a Tn917 transposon that was 5.1 kb in size34. Tn916Sp − 11 A and Tn916Sp − SPNXDRSMC171032 had a 5.3 kb Tn917 and a 2.8 kb ISL3 inserted internally, respectively. The Tn917s that slightly varied in size all had perfect IRs (5’- GGGGTCCCGAGCGC-3’) and 5 bp DRs (5’-TACCT-3’). Tn916Sp − NT11058 had an 8.5 kb composite transposon formed by ISL3, carrying two Erm family resistance genes and two aminoglycoside resistance genes. Both ISL3 and Tn917 contain one Erm family resistance gene. Tn608735 is highly similar Tn916Bs − BS49−1 but harbours an IS1216 composite transposon.

In Streptococcus pneumoniae, Tn916, like Tn1545, also carries erythromycin and kanamycin resistance genes7 but these were not found in Tn1545 in this study. Tn6002 is consistent with Tn916Sp − 574, Tn2010 is close in size to Tn916Sp − 11 A and Tn916Sp − SPNXDRSMC171032, and both harbour a 2.8 kb ISL3, but the other inserted transposons differ11.

In this study, we identified and classified Tn916 and other members of this family across a wide range of bacterial genomes. Our analysis revealed that these transposons share common structural features, such as AT-rich IRs and conserved stem‒loop structures at their boundaries. The presence of antibiotic resistance genes, including those involved in tetracycline and vancomycin resistance, highlights the role of the Tn916 family in the dissemination of antimicrobial resistance. We also found that genomes with lower GC contents more frequently harbour Tn916 elements, suggesting a preference for AT-rich integration sites. These findings enhance our understanding of the structural diversity and integration mechanisms of Tn916 and other members of this family, providing a foundation for future research aimed at controlling the spread of antibiotic resistance mediated by these conjugative transposons.

Tn916 and its family’s upstream and downstream stem-loop structures. (1) The longer IRs are drawn as 8 bp, and the shorter ones are drawn as 6 bp. (2) In the depicted stem-loop structures, N and M denote degenerate nucleotides within the upstream and downstream loop regions, respectively, with subscript numbers indicating their topological positions (5′→3′ orientation). (3) Conserved base requirements are defined as follows: For the upstream loop, position 1 must be adenine (A) or position 5 must be thymine (T) (at least one criterion required); an identical statistical constraint applies to the downstream loop.

Modular structure of Tn916 and its family. (1) Genes whose functions cannot be proven are shown in a lighter color than the speculated possible modules; transposases are shown in orange. (2) 7: a sigma factor; 8: a potential transcription-regulating. (3) The percentages associated with the excisionase (xis) and integrase (int) of other members in the Tn916 family represent the sequence identity to their respective homologs (xis/int proteins) in the canonical Tn916 element.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Dobrindt, U., Hochhut, B., Hentschel, U. & Hacker, J. Genomic Islands in pathogenic and environmental microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2 (5), 414–424 (2004).

Mullany, P., Roberts, A. P. & Wang, H. Mechanism of integration and excision in conjugative transposons. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59 (12), 2017–2022 (2002).

Wright, L. D. & Grossman, A. D. Autonomous replication of the conjugative transposon Tn916. J. Bacteriol. 198 (24), 3355–3366 (2016).

van Hoek, A. H. et al. Acquired antibiotic resistance genes: an overview. Front. Microbiol. 2, 203 (2011).

Shoemaker, N. B., Smith, M. D. & Guild, W. R. DNase-resistant transfer of chromosomal Cat and tet insertions by filter mating in Pneumococcus. Plasmid 3 (1), 80–87 (1980).

Franke, A. E. & Clewell, D. B. Evidence for a chromosome-borne resistance transposon (Tn916) in Streptococcus faecalis that is capable of conjugal transfer in the absence of a conjugative plasmid. J. Bacteriol. 145 (1), 494–502 (1981).

Clewell, D. B., Flannagan, S. E. & Jaworski, D. D. Unconstrained bacterial promiscuity: the Tn916-Tn1545 family of conjugative transposons. Trends Microbiol. 3 (6), 229–236 (1995).

Gawron-Burke, C. & Clewell, D. B. A transposon in Streptococcus faecalis with fertility properties. Nature 300 (5889), 281–284 (1982).

Bertsch, D. et al. Tn6198, a novel transposon containing the Trimethoprim resistance gene DfrG embedded into a Tn916 element in Listeria monocytogenes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68 (5), 986–991 (2013).

Warburton, P. J., Palmer, R. M., Munson, M. A. & Wade, W. G. Demonstration of in vivo transfer of Doxycycline resistance mediated by a novel transposon. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60 (5), 973–980 (2007).

Li, Y. et al. Molecular characterization of erm(B)- and mef(E)-mediated erythromycin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in China and complete DNA sequence of Tn2010. J. Appl. Microbiol. 110 (1), 254–265 (2011).

Hirt, H. et al. Characterization of the pheromone response of the Enterococcus faecalis conjugative plasmid pCF10: complete sequence and comparative analysis of the transcriptional and phenotypic responses of pCF10-containing cells to pheromone induction. J. Bacteriol. 187 (3), 1044–1054 (2005).

Rice, L. B. et al. Multiple copies of functional, Tet(M)-encoding Tn916-like elements in a clinical Enterococcus faecium isolate. Plasmid 64 (3), 150–155 (2010).

Iannelli, F., Santoro, F., Oggioni, M. R. & Pozzi, G. Nucleotide sequence analysis of integrative conjugative element Tn5253 of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58 (2), 1235–1239 (2014).

Huang, J. et al. Evolution and diversity of the antimicrobial resistance associated mobilome in Streptococcus suis: A probable mobile genetic elements reservoir for other Streptococci. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 6, 118 (2016).

Khan, U. B. et al. Genomic analysis reveals new integrative conjugal elements and transposons in GBS conferring antimicrobial resistance. Antibiot. (Basel). 12 (3), 544 (2023).

Roberts, A. P. & Mullany, P. A modular master on the move: the Tn916 family of mobile genetic elements. Trends Microbiol. 17 (6), 251–258 (2009).

Roberts, A. P. & Mullany, P. Tn916-like genetic elements: a diverse group of modular mobile elements conferring antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35 (5), 856–871 (2011).

Su, Y. A., He, P. & Clewell, D. B. Characterization of the tet(M) determinant of Tn916: evidence for regulation by transcription Attenuation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 36 (4), 769–778 (1992).

Celli, J. & Trieu-Cuot, P. Circularization of Tn916 is required for expression of the transposon-encoded transfer functions: characterization of long tetracycline-inducible transcripts reading through the attachment site. Mol. Microbiol. 28 (1), 103–117 (1998).

Salyers, A. A., Shoemaker, N. B., Stevens, A. M. & Li, L. Y. Conjugative transposons: an unusual and diverse set of integrated gene transfer elements. Microbiol. Rev. 59 (4), 579–590 (1995).

He, Z. et al. Evolview v2: an online visualization and management tool for customized and annotated phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (W1), W236–W241 (2016).

Santoro, F., Oggioni, M. R., Pozzi, G. & Iannelli, F. Nucleotide sequence and functional analysis of the tet (M)-carrying conjugative transposon Tn5251 of Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 308 (2), 150–158 (2010).

Browne, H. P. et al. Complete genome sequence of BS49 and draft genome sequence of BS34A, Bacillus subtilis strains carrying Tn916. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 362 (3), 1–4 (2010).

Dong, D. et al. Genetic analysis of Tn916-like elements conferring Tetracycline resistance in clinical isolates of Clostridium difficile. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 43 (1), 73–77 (2014).

Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W. et al. Retail ready-to-eat food as a potential vehicle for Staphylococcus spp. Harboring antibiotic resistance genes. J. Food Prot. 77 (6), 993–998 (2014).

Cui, L. et al. Detection of cfr(B)-carrying clinical Enterococcus faecium in China. J. Glob Antimicrob. Resist. 26, 262–263 (2021).

Brouwer, M. S. et al. Genetic organisation, mobility and predicted functions of genes on integrated, mobile genetic elements in sequenced strains of Clostridium difficile. PLoS One. 6 (8), e23014 (2011).

Garnier, F. et al. Characterization of transposon Tn1549, conferring VanB-type resistance in Enterococcus spp. Microbiol. (Reading). 146 (Pt6), 1481–1489 (2000).

McDougal, L. K. et al. Detection of Tn917-like sequences within a Tn916-like conjugative transposon (Tn3872) in erythromycin-resistant isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42 (9), 2312–2318 (1998).

Caparon, M. G. & Scott, J. R. Excision and insertion of the conjugative transposon Tn916 involves a novel recombination mechanism. Cell 59 (6), 1027–1034 (1989).

Rubio-Cosials, A. et al. Transposase-DNA complex structures reveal mechanisms for conjugative transposition of antibiotic resistance. Cell 173 (1), 208–220 (2018).

Du, D. et al. Multidrug efflux pumps: structure, function and regulation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16 (9), 523–539 (2018).

Shaw, J. H. & Clewell, D. B. Complete nucleotide sequence of macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B-resistance transposon Tn917 in Streptococcus faecalis. J. Bacteriol. 164 (2), 782–796 (1985).

Ciric, L., Mullany, P. & Roberts, A. P. Antibiotic and antiseptic resistance genes are linked on a novel mobile genetic element: Tn6087. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66 (10), 2235–2239 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the authors for the public data used in the study.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

(I) Conception and design: LS; (II) Collection and assembly of data: LS, JD, TRL, JJS, ZLH; (III) Data analysis and interpretation: LS, JD, TRL, JJS, ZLH; (IV) Manuscript writing: All authors; (V) Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The used data were publicly available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, L., Duan, J., Liu, T. et al. Characteristics of the integration sites and module structures of the Tn916 and its family. Sci Rep 15, 23803 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09579-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09579-7