Abstract

Examination of farmers’ behaviors regarding pesticide application is crucial because of their influential impacts on exposure levels and general health. This research assessed pesticide-related behaviors among 151 rice farmers in Gilan Province, Iran, with a focus on their behaviors before, during, and after pesticide spraying and related health symptoms. The findings indicated that government agencies and pesticide sellers were the main sources of information on pesticides for farmers. About 83% of farmers used storerooms for the safekeeping of pesticides, while only 55% of them reported using personal protective equipment. A majority of farmers followed safety measures after spraying. Of the types of personal protective equipment, masks were the most used (80%). Neurological (35%) and respiratory (34.4%) symptoms were the most reported symptoms. Neglecting to shower was associated with ear, nose, and throat symptoms (p = 0.014), and failure to change clothes was linked to neurological and musculoskeletal symptoms (respectively, p = 0.001, p = 0.006). Eating food after spraying was associated with neurological, urological, and skin symptoms (respectively, p < 0.001, p < 0.001, p < 0.001), eating vegetables after spraying was linked to the presence of digestive symptoms (p = 0.047), and drinking water after spraying was associated with musculoskeletal symptoms (p = 0.001). Targeted education campaigns, in addition to direct monitoring and continuous research, should be conducted among farming communities in northern Iran to encourage the use of safe spraying behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nearly 1.8 billion people worldwide are directly involved in agricultural work1, a figure that is particularly significant in developing countries. With the world population projected to reach nine billion by 2050, the importance of agriculture and food production becomes even more critical2. Rice is a staple food in many world countries around the world3. Therefore, a surge in the quantity and quality of this product is vital4, and in order to achieve these goals, pest control is necessary3,4,5,6.

Farmers rely on pesticides to protect crops, often calling for the government to ensure supply adequacy1,3. The use of pesticides has become a key element of modern agricultural practices. Farmers worldwide use more than three million tons of these chemical compounds every year7,8,9. Some of the classes of pesticides are organochlorines, organophosphates, and neonicotinoids. Pesticides are also grouped by their particular uses, which are herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, and rodenticides7,10,11,12. These chemicals find their way into the soil or plants through numerous pathways, such as fertilizers, irrigation systems, and direct application methods11.

Development of resistance among pest populations to chemical compounds may lead to the intensification of the use of pesticides and the rendering of new variants year after year6,13. As the beneficial properties of such compounds are sought, they, at the same time, have side effects on the health of humans and the environment7,14. These chemicals tend to accumulate inside plant and animal tissues, hence penetrating the food chain of humans3. Cases of exposure to such compounds have been reported to cause a chain of symptoms ranging from headache and excessive saliva to tearing, nausea, and convulsions, to other critical diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. Interaction with compounds of organophosphorus hinders the functioning of the cholinesterase enzyme, whose disruption may lead to the development of neurological diseases. Various instances have been reported with respect to the outbreak of diseases among agriculture workers who did not follow guidelines of safety measures3,7,15.

Epidemiological studies have reported potential associations between residential proximity to agricultural fields where pesticides are applied and a variety of adverse health effects. These effects are reproductive problems, including preterm birth, impaired fetal growth, neural tube defects, hypospadias, gastroschisis, and anotia; cognitive impairments, which comprise autism spectrum disorders and reductions in intelligence quotient (IQ), verbal comprehension, and attention span; respiratory diseases, including asthma; as well as grave diseases such as breast cancer, brain tumors, Parkinson’s disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis16. In addition, illiteracy among some farmers constrains their ability to read the warnings placed on pesticide labels, thereby resulting in failure to follow established safety precautions2.

Research suggests personal protective measures such as the use of masks and gloves, the use of appropriate sprayer techniques, and the disposal of used pesticide containers significantly reduce the risk to their health. However, to increase the overall level of adoption of such safety guidelines, it is critical to increase farmers’ awareness and knowledge with respect to the safety of pesticides1,14,15.

Occupational health is a major concern in developed nations but often gets inadequate attention in many developing countries. The assessment of exposure to pesticides in agricultural settings is critical in establishing the health risks that are associated with pesticide use, especially in developing countries where legislation controlling occupational hygiene is either lacking or ineffective. It is therefore necessary to measure the concentrations of pesticides in rural settings and their surrounding environments in such developing contexts17.

The geographical and climatic conditions of the north of Iran are most favorable for rice cultivation, resulting in the use of pesticides by farmers to protect their crops. However, there is limited literature relating to the trend of pesticide use among Iranian rice farmers. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the occupational use of pesticides among farmers and the practices carried out before, during, and after the application of the chemicals, along with the impact of such practices on the development of clinical symptoms. During the course of this study, the researchers endeavored to identify whether farmers who cultivate rice develop occupational health problems following exposure to the use of chemicals.

Methods

Research setting

The current study was conducted in the Gilan province of northern Iran, focusing on the Masal and Anzali counties (see Fig. 1). The region is known to be involved in rice production. There are 95 villages in Masal County and 28 in Anzali County. Sampling was conducted among the rice-farming villages, covering around 70% of the villages of Masal and around 60% of the Anzali villages.

Temporal context and research methodology

The study was carried out in 2022 with the aim of evaluating the practices relating to the use of pesticides among rice farmers in three phases: before, through, and after the spraying period. Pesticides are applied at the start of May till the start of July. The study began simultaneously in selected cities at the beginning of July and lasted for another month. The cross-sectional study design strategy was used, focusing on the evaluation of the relationship between farmers’ use of pesticides and the reported symptoms of disease.

Data collection

The data collection procedure was conducted via direct interviews, using a structured questionnaire developed by the researchers3,18,19,20. The instrument was applied to a sample of 151 farmers from both counties. The data collected included demographic information (age, level of education, history of smoking, and agricultural land size) and extensive questions on pesticide use before, during, and after spraying, and recording any health symptoms that appeared after application. The questionnaire is attached in the Supplementary material. Some of the data was collected using observational methods, as some of the farmers did not have the proper knowledge to specify the types of pesticides they used. In cases where such farmers were found, they were asked to bring the containers and/or packaging of the pesticides they used, so that the interviewer could record the relevant information systematically. This was done to increase the accuracy and reliability of the information collected.

The WHO classifications of toxicity are given in Table 1. The WHO classifies pesticides into the following categories: II: Moderately hazardous; III: Slightly hazardous; U: Unlikely to pose an acute hazard in normal use; NC: Not classifiable.

The numerous symptoms from specific bodily systems reported by the farmers were characterized in the following ways:

-

Respiratory symptoms such as cough, thoracic pain, and difficulties with breathing.

-

Musculoskeletal symptoms such as numbness, cramps, and muscle weakness.

-

Clinical features involving the gastrointestinal tract are reduced appetite, diarrhea, and abdominal pain.

-

Ear, nose, and throat symptoms may involve multiple indicators ranging from rhinorrhea, feelings of burn and dryness in the nasal cavities, anosmia, pharyngeal dryness, pharyngodynia, pain around the ears, and instances of dizziness.

-

Visual symptoms: Reduced vision, eye discomfort (redness or tearing).

-

Dental pain

-

Urological symptoms are increased urinary frequency, urgency, dysuria, and a reduced urine stream.

-

Cutaneous manifestations such as lesions, vesicle formation, or nail fragility.

-

Neurological and behavioral effects cover a range that includes dizziness, seizures, weakness, poor balance, nausea, convulsions, and headaches.

Sampling

The Jihad-e-Keshavari Organization, responsible for agriculture management in Iran, provided the names of farmers working in Masal and Anzali counties. Initially, 206 farmers showed willingness to participate, but eventually, 151 were ultimately included in the study (70 from Masal County and 81 from Anzali County), because only the farmers who personally performed the preparation and spraying of pesticides were included in our study. The research team made field visits to motivate farmers to participate in the investigation. The farmers were selected on the basis of rice cultivation methods and individual application of pesticides.

Questionnaire development and validity

The questionnaire used in the current study was developed following the conceptual framework of the available literature on the application of the pesticide and its resultant health implications19,21,22. All the referenced articles, whose findings had been synthesized to develop the questionnaire, were carried out using the English language. After the development of the questionnaire, it was translated to Persian and adjusted to meet regional cultural and linguistic requirements. The face and content validity of the questionnaire were ensured through the consensus of five environmental experts and an expert of the Persian language. Pilot study involving 25 farmers, who were later excluded from the study, was carried out to test the questionnaire’s reliability. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, calculated from the pilot study, came out to be 74%, depicting an acceptable level of reliability.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of the data was performed using SPSS version 19 along with Microsoft Excel. Correlation tests were used to test the correlation between numerical variables, while the correlation between nominal values was tested using the chi-square test. The use of the t-test and ANOVA (with their non-parametric analogues) was further used to compare the mean or median between two or more groups. Crude and adjusted (multiple) logistic regression was performed to estimate the odd ratios and control for potential confounding factors.

Ethical statement

Before starting data collection, all participants were informed about the work procedures and signed an informed consent form. The study was conducted with the approval of the ethical guidelines declared in the Declaration of Helsinki and the Singapore Statement on Research Integrity. The study subjects were provided with detailed information about the goal and methods used in the study. The study only included male farmers, since all the activities involving the use of pesticides were only done by men. The study also had the approval of the Khalkhal University of Medical Sciences Ethics in Research Committee (Ethics Code: IR.KHALUMS.REC.1401.011).

Results

Characteristics of study cohort and pesticide application incidence

A total of two hundred and six male farmers from both Masal and Anzali counties showed enthusiasm to partake in this study. The average age of the study’s subjects was 49.87 years, with 13.56 years of standard deviation. Each farmer had an average land area of 3.83 hectares, where they grew rice. About one-third of the farmers, 32.4%, were smokers, and 65% of them reported having completed high school or below such education, showing no university education. The large majority, totaling 94.6%, used pesticides for pest control. The rest used them mainly to copy what their neighbors were practicing. The most common percentage of the subjects, 81.2%, received information on the use of the pesticides from various information sources such as pesticide dealers and the media. The information on the application of the pesticides came often from governments and the dealers of the pesticides. Interestingly, 30.6% of farmers admitted to having little information on the diluting weights of the proper use of the pesticides. Also, a large number of the farmers (3.7%) claimed to have mixed and applied the pesticides themselves. The large majority, totaling 98.1%, purchased the pesticides from licensed selling institutions. The rest of the farmers went through alternative procurement methods such as their neighbors or unauthorized dealers who involved prohibited pesticide selling. Over one-third of the farmers, 35.1%, discarded the containers of empty pesticides in regular garbage, while 22.7% sold them. About 17% burned the containers, and 15.5% buried them underground (see Table 2).

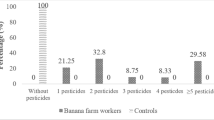

Pesticide categories used for rice production in Iran

When it comes to the types of pesticides analyzed, herbicides constituted the largest category used, taking up 77.9% of the total, followed by 57.9% for insecticides and 41.8% for fungicides. During the course of the study, 30 unique pesticides being used cumulatively were noted. About 37% of the noted pesticides were included under toxicity category II (moderately hazardous) according to the World Health Organization’s classification, with only 3% falling under toxicity category III (slightly hazardous).

Farming practices for pesticide use by farmers

Farmers’ pre-application practices before applying pesticides

Among the 206 farmers who took part in the study, only 151 carried out the premixing and application of pesticides themselves, thus omitting those who outsourced the work to others. The answers to the foregoing questions are summarized in Table 3. Alas, even though the majority of the study’s participants (81.2%) reported having received information on the preparation and application of the pesticides from multiple sources (see Table 2), there were farmers who did not read the labels and follow the safety guidelines when carrying out dilution and application. To the specific question of never reading the labels on the containers of the pesticides, 21.2% of the respondents admitted to never doing so, and 24.5% admitted to having ignored the dilution guidelines specified on the labels thereof (see Table 3).

The results obtained from the chi-square test showed the lack of a statistically significant relationship between educational levels and the activities of reading labels on packages as well as dilution in accordance with those labels (χ2 = 6.75, p = 0.334; χ2 = 3.74, p = 0.697). The test further showed that participants’ average age that read labels on cans (48.82 ± 13.59) was significantly lower (t = − 2.56, p = 0.011) than that of those that did not practice reading labels (54.71 ± 11.73). The majority (74.2%) of the interviewed farmers indicated they apply pesticide when they are standing downwind.

Farmers’ views on use of personal protected equipment (PPE)

The findings relating to the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) from section three of the questionnaire administered are shown in Table 4. Data revealed that most respondents did not use goggles (70.1%), nor did they wear coveralls (74.2%). Conversely, masks were found to be the most widely used PPE, as 80% of the participants reported using them. The median score measuring the use of the equipment did not show statistically significant differences among various educational levels (P-value = 0.908, Kruskal–Wallis = 0.550). However, a positive correlation between the use of PPE and age was found using Spearman correlation analysis (r = 0.23, p = 0.004), while no correlation was found between the use of PPE and area planted (r = 0.056, p = 0.500).

Practices of farmers about the use of PPE

Table 5 presents an overview of farmers’ practices followed after spraying, as described in section four of the questionnaire. The vast majority of farmers used safety measures after spraying. Precisely, about 83% of them washed their hands and face, about 77% showered immediately after spraying, and about 74% did not eat or drink on the farm while and shortly after spraying was done.

Prevalence of self-reported symptoms of toxicity related to pesticide exposure

Table 6 depicts the prevalence of symptoms reported by the farmers. Neurological symptoms were the most common, at 35%, followed by respiratory symptoms, at 34.4%.

Prominent correlations were seen among particular behavior patterns upon pesticide exposure and the development of symptoms related to health. Showering correlated with ear, nose, and throat (ENT) issues (χ2 = 6, p = 0.014), while the change of clothes related to neurological and musculoskeletal disorders (χ2 = 10.33, p = 0.001; χ2 = 7.42, p = 0.006). In addition, consumption of meals and consumption of vegetables were related to neurological, urological, and skin disorders (χ2 = 14.48, p < 0.001; χ2 = 15.15, p < 0.001; χ2 = 9.18, p < 0.001) and vegetable consumption with gastrointestinal disorders (χ2 = 3.95, p = 0.047). Conversely, consumption of water correlated with musculoskeletal disorders (χ2 = 8.05, p = 0.001). Farmers who did not shower after pesticide application, did not change clothes, did not consume meals or vegetables, or did not consume water in the field post-work showed a greater likelihood of reporting one or more of the symptoms.

Analysis of adjusted and crude odds ratios (ORs) revealed a number of strong correlations between various risk factors and symptoms of illness. Cigarette smoking appeared to be highly correlated with highly elevated odds of having symptoms in several bodily systems, namely, in the form of respiratory, digestive, musculoskeletal, ocular, and neurological symptoms. More specifically, the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) for musculoskeletal symptoms was found to be 3.84 (p = 0.007), for digestive symptoms 3.67 (p = 0.025), for ocular symptoms 1.16 (p = 0.780), and for neurological symptoms 2.98 (p = 0.014), which indicates a highly raised likelihood among smokers. By way of some contrast, the wear of protective boots appeared to be consistently correlated with highly reduced odds for having symptoms in a number of categories, most notably in the areas of respiratory (AOR = 0.171, p = 0.001), digestive (AOR = 0.028, p < 0.001), ocular (AOR = 0.032, p < 0.001), dermal (AOR = 0.099, p < 0.001), and neurological (AOR = 0.247, p = 0.008) symptoms. Such a discovery highlights the value of protective boots in reducing occupational health threats (Table 7).

In contrast, most of the personal protective equipment (PPE), such as gloves, coveralls, and eye-wear, showed either limited effects or, in some cases, a greater likelihood of symptomatology. More specifically, the use of gloves correlated with higher odds of developing digestive (AOR = 7.12, p = 0.016) and ocular (AOR = 4.24, p = 0.041) symptoms, in all likelihood explained by reverse causality, in which the use of PPE increases in parallel with the development of symptoms. The size of cultivated agricultural area did not consistently predict poor outcomes; although it showed a borderline crude association with urological symptoms (crude OR = 3.51, p = 0.049), this association did not persist in the adjusted model (AOR = 2.56, p = 0.098).

Discussion

This study provides important information about the hazards of pesticide use among farmers in Iran. Our study showed that the storage and disposal of containers is a matter of concern. In our study, 15.5% farmers buried the empty containers on the farm, 35.1% discarded them in the trash bin, 22.7% sold, and 17.5% incinerate them. Jallow et al. showed that 50% of farmers in Kuwait disposed empty containers in trash bins or did other unsafe practices such as discarding on the farm (27%), incinerating on the farm (43%), reusing (6%), and burying on the farm (25%); and only 39% reported disposing in hazardous waste collection sites19. These dangerous disposing methods can lead to significant environmental and human health problems23,24. The safest method for disposal of empty pesticide containers is disposing in hazardous waste collection sites, but these sites do not exist in most Iranian cities.

The findings of the present study regarding farmers’ sources of information on pesticide use are somewhat consistent with previous studies but also show notable differences. In the present study, 81.2% of farmers obtained information from multiple sources, with government agencies (35.1%) and pesticide suppliers (29.2%) being the primary sources. This suggests a relatively diversified approach to information-seeking among Iranian farmers. In contrast, Tsakiris et al. found that 50.5% of farmers had low or potentially low use of information sources, while the remaining 49.5% had potentially or very high use. Additionally, agricultural supply stores were the main information providers for 88.1% of farmers in their study25. Both studies highlight that farmers rely on external sources (government agencies, suppliers, or agricultural stores) rather than self-education or scientific literature. However, the present study shows a higher reliance on multiple sources (81.2%), whereas Tsakiris et al. found a more polarized distribution (nearly half of farmers had low information-seeking behavior). The dominant role of pesticide suppliers and agricultural stores aligns with the findings of Tsakiris et al., though the exact proportions differ.

Storing pesticides in living areas can greatly increase the potential for high toxic exposure, especially if it is stored in places where farmers prepare food, eat, and sleep. In Iran storerooms are often left unlocked, making them accessible to children. In our study, around 83% of farmers stored pesticides in the storeroom, while 11.3% stored them in other places, such as inside their homes. Results of Jallow et al. in Kuwait showed that 59% of the farmers used locked chemical storage units, 34% used open sheds, and 30% stored pesticides openly. However, 15% stored pesticides in inappropriate places, 8% in regular fridges, and 20% within living areas19. In a study conducted by Sankoh et al., on rice farmers of Sierra Leonean, only 27% of farmers stored pesticides in the storeroom3.

In the present study, 12.2% of the farmers were illiterate. The majority of farmers were capable of reading labels, and prepared pesticides according to proper information sources such as the pesticide seller; and stored unused residuals in a storeroom. However, reading the labels does not always guarantee a complete understanding of the information. Sankoh et al. found that only 20.6% of the farmers who were able to read, fully comprehended the instructions written on the labels3. Other studies showed, farmers who read pesticide labels demonstrated better safety practices in handling pesticides compared to those who couldn’t read the labels26, and safety had a negative correlation with illiteracy. Several other studies27,28,29,30, also confirmed a link between literacy levels and pesticide safety practices. Collectively, these studies provide substantial evidence that education and literacy significantly impact the use of PPE and safe handling of pesticides31.

A number of different types of personal protective gear (PPE)—including gloves, boots, hats, long-sleeve shirts, and chemical-resistant coveralls—is utilized in pesticide handling in an endeavor to minimize exposure through the skin. The choice of PPE depends on a number of different factors, including exposure conditions, pesticide toxicity, and preference. Gloves and boots are often considered the minimum PPE for most pesticide applications. In cases involving highly toxic pesticides, the use of more than one form of PPE is advised in an effort to minimize exposure further32. From our research, we found that a large percentage of participants reported the usage of gloves, boots, and masks, with usage ranging from 75.5% to 80%, and that older farmers showed a greater tendency to utilize PPE. Sapbamrer et al. study found that a large percentage of Thai rice farmers, ranging from 74 to 96%, utilized some form of PPE5. However, in a study by Okoffo et al. of Ghanaian cocoa farmers, a mere 35% of them utilized complete PPE when spraying pesticides, while about 20% applied pesticides with no protective clothing, and most (45%) applied only partial PPE when spraying33. These findings imply that usage of PPE varies among different populations and is perhaps subject to demographic, structural attributes of the farms, behavior and psychosocial factors, as well as physical settings31.

It is essential to follow safety instructions immediately after spraying pesticides, as well. According to our results, the majority of the farmers took a shower, and changed and washed their clothes after spraying; and only a few percent of them consumed meals, vegetables, or water around or inside the farm immediately after spraying. Interestingly, these behaviors were not found to be related to the participants’ level of education. Following safety instructions post spraying plays a crucial role in protection against pesticide exposure. In Okoffo et al. study, 55.8% and 45% of participants drank water or alcohol, or ate food during and after pesticide application33. Also, data from a study by Mubushar et al. in Pakistan reported that only 45.6% of the farmers always showered, and 54.4% did so sometimes, after pesticide application20. Raimi et al. reported that only about 70% of the farmers in their study in Nigeria wash hands with water or both water and soap after using pesticides34.

Our findings showed that symptoms found in neurological, respiratory, ocular, dermal, and gastrointestinal systems were more common among farmers compared to other symptom groups. More specifically, neurological and respiratory symptoms were notably more common, perhaps due to the extensive exposure of those organ systems during pesticide application procedures. Our findings support those of several previous studies. Lekei et al., for example, reported headaches and skin irritation as common symptoms in their study18. Likewise, Jallow et al. reported cases of itchy eyes and headaches among the farmers following exposure to pesticides19. These findings support the susceptibility of particular organ systems to the deleterious effects of pesticide exposure18,19.

Regarding PPE, the use of protective boots showed a consistently significant association with all symptoms, except for dental symptoms, after adjusting for other factors. The use of hats was also associated with less musculoskeletal symptoms, and gloves showed significant associations with digestive and eye symptoms. Coveralls and masks were found to have significant associations with eye and neurological symptoms, respectively. Also, it was found that only about 56% of the participants used PPE and 20% of the total participants reported experiencing symptoms after pesticide spraying. In the study of Memon et al. over 55% of the respondents did not use any protective equipment while picking cotton. Moreover, having up to 16 years of experience in picking was associated with using more personal protective equipment; and when their experience exceeded 16 years, there was less usage of PPE. Also, less use of PPE was associated with more skin and eye injuries, headaches, stomachaches, and fevers. But, no significant relation was found between the use of gloves and symptoms35.

This was one of the few studies that has assessed the safety behaviors of farmers in Iran, and the studies about rice farmers are even less. A study in Mazandaran Province, in northern Iran was conducted by Sharifzadeh et al. to investigate the determinants of farmers’ safety behavior when working with pesticides. In this study, only a small percentage practiced safe behaviors; 8.9% used PPE, 8.6% followed the safety rules when using pesticides, 2.7% adhered to hygienic practices after pesticide application, and 2.4% avoided health hazards. Additionally, the results of this study indicated that the farmers’ understanding of the importance of various safety measures when using pesticides was not fully reflected in their practices. But our study conducted in the neighboring province showed that rice farmers had a higher level of compliance with safety behaviors when using pesticides30. In another study conducted by Bagheri et al. on farmers in northwestern Iran, nearly 30% of farmers discarded the leftover pesticide solution used in sprayers. Regarding the washing of sprayers, 55.3% washed them in their yard, 21% in rivers or canal flows, and 14.7% in farm water sources. About 64.3% reported leaving the wash materials on the farm, while around 34.0% disposed them into rivers or canal flows. Most farmers wore pants and shirts when working with pesticides, and fewer used masks, gloves, or hats36. Whereas in our study, most respondents used gloves, boots, and masks (75.5–80%).

This study has some limitations that need to be noted. Firstly, the information gathered in this study depended on self-reporting. The researchers explained their aim to the participants and guaranteed them anonymity, yet the possibility of some respondents reporting misinformation, especially about the use of PPE to conform to socially desirable responses, exists. In addition, the reported symptoms may not be caused by pesticide exposure exclusively, since some other factors may have affected symptoms in some of the farmers. Another limitation is the fact that the farmers did not check for their clarification in relation to labels, encompassing color codes and toxicity signs. In this regard, even those participants who read the labels and supporting information might not grasp the meanings and intricacies involved in the contained information. Last, the application of findings from this study is constrained by the limited sample size. The study examined a small sample of participants, and hence, they may not be representative of the whole number of Iranian rice cultivators. Therefore, therefore, a need for prudence should be exercised in using the findings to make inferences about other agricultural populations. Our aim, however, was to examine and draw attention to important occupational health issues and pesticide safety concerns in, and among, farmers. Regardless of its limitation, this study sheds light on pesticide safety procedures among Iranian farmers and underscores the need for intervention through specifically designed educational approaches and regulations to protect the health of farmers.

Conclusions

The findings of this study highlight significant gaps in pesticide safety knowledge and practices among rice farmers in Iran, despite most receiving some form of instruction. The widespread use of moderately hazardous pesticides, improper disposal of containers, and inconsistent adherence to safety measures; such as reading labels, using PPE, and post-application hygiene, contribute to a high prevalence of self-reported toxicity symptoms, particularly neurological and respiratory issues. The strong association between unsafe practices (e.g., not showering post-application, eating on the farm) and adverse health outcomes underscores the urgent need for targeted educational interventions. Practical steps should include mandatory training programs emphasizing proper pesticide handling, dilution, and disposal, as well as stricter enforcement of safety regulations by agricultural authorities. Additionally, promoting accessible and affordable PPE, especially protective boots, could significantly reduce exposure risks, given their demonstrated protective effects.

Future research should focus on evaluating the effectiveness of educational interventions in changing farmers’ behaviors and reducing pesticide-related health symptoms. Longitudinal studies could assess whether improved safety practices lead to measurable declines in acute and chronic health issues over time. Furthermore, investigations into the socioeconomic barriers to PPE adoption; such as cost, availability, and comfort, could inform more practical solutions. Given the reliance on pesticide dealers for information, engaging them as key stakeholders in disseminating safety guidelines may enhance compliance. Finally, exploring alternative pest management strategies, such as integrated pest management (IPM), could reduce reliance on hazardous chemicals while maintaining crop yields. Such studies should prioritize actionable outcomes that directly benefit farming communities, ensuring both health protection and sustainable agricultural productivity.

Data availability

The datasets used during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Al-Zaidi, A. A., Baig, M. B., Muneer, S., Hussain, S. M. & Aldosari, F. O. Farmers’ level of knowledge on the usage of pesticides and their effects on health and environment in northern Pakistan. (2019).

Tripathi, A., Mishra, R., Maurya, K., Singh, R. & Wilson, D. 3–24 (2019).

Sankoh, A. I., Whittle, R., Semple, K. T., Jones, K. C. & Sweetman, A. J. An assessment of the impacts of pesticide use on the environment and health of rice farmers in Sierra Leone. Environ. Int. 94, 458–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.05.034 (2016).

Fuhrimann, S. et al. Exposure to multiple pesticides and neurobehavioral outcomes among smallholder farmers in Uganda. Environ. Int. 152, 106477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2021.106477 (2021).

Sapbamrer, R. & Nata, S. Health symptoms related to pesticide exposure and agricultural tasks among rice farmers from Northern Thailand. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 19, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12199-013-0349-3 (2014).

Kori, R. K., Thakur, R. S., Kumar, R. & Yadav, R. S. Assessment of adverse health effects among chronic pesticide-exposed farm workers in Sagar District of Madhya Pradesh, India. Int. J. Nutr. Pharmacol. Neurol. Dis. 8, 153–161. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijnpnd.ijnpnd_48_18 (2018).

Quansah, R. et al. Associations between pesticide use and respiratory symptoms: A cross-sectional study in Southern Ghana. Environ. Res. 150, 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2016.06.013 (2016).

Baqar, M. et al. Organochlorine pesticides across the tributaries of River Ravi, Pakistan: Human health risk assessment through dermal exposure, ecological risks, source fingerprints and spatio-temporal distribution. Sci. Total Environ. 618, 291–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.10.234 (2018).

Li, Z. The use of a disability-adjusted life-year (DALY) metric to measure human health damage resulting from pesticide maximum legal exposures. Sci. Total Environ. 639, 438–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.05.148 (2018).

Amoatey, P., Al-Mayahi, A., Omidvarborna, H., Baawain, M. S. & Sulaiman, H. Occupational exposure to pesticides and associated health effects among greenhouse farm workers. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 22251–22270 (2020).

Tariq, M. I., Afzal, S., Hussain, I. & Sultana, N. Pesticides exposure in Pakistan: A review. Environ Int 33, 1107–1122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2007.07.012 (2007).

Yu, Z., Li, X.-F., Wang, S., Liu, L.-Y. & Zeng, E. Y. The human and ecological risks of neonicotinoid insecticides in soils of an agricultural zone within the Pearl River Delta, South China. Environ. Pollut. 284, 117358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117358 (2021).

Shammi, M. et al. Pesticide exposures towards health and environmental hazard in Bangladesh: A case study on farmers’ perception. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 19, 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2018.08.005 (2020).

Bondori, A., Bagheri, A., Allahyari, M. S. & Damalas, C. A. Pesticide waste disposal among farmers of Moghan region of Iran: Current trends and determinants of behavior. Environ. Monit. Assess. 191, 30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-018-7150-0 (2018).

Ahmad, S. A., Anzar, A., Tariq, A. & Altaf, K. F. A review on pesticides related health effects in agricultural workers of Sindh, Pakistan. Pure Appl. Biol. (PAB) 8, 1975–1979 (2019).

Dereumeaux, C., Fillol, C., Quenel, P. & Denys, S. Pesticide exposures for residents living close to agricultural lands: A review. Environ. Int. 134, 105210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2019.105210 (2020).

Khan, M. & Damalas, C. A. Occupational exposure to pesticides and resultant health problems among cotton farmers of Punjab, Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 25, 508–521 (2015).

Lekei, E. E., Ngowi, A. V. & London, L. Farmers’ knowledge, practices and injuries associated with pesticide exposure in rural farming villages in Tanzania. BMC Public Health 14, 389. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-389 (2014).

Jallow, M. F. A., Awadh, D. G., Albaho, M. S., Devi, V. Y. & Thomas, B. M. Pesticide knowledge and safety practices among farm workers in Kuwait: Results of a survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 340 (2017).

Mubushar, M., Aldosari, F. O., Baig, M. B., Alotaibi, B. M. & Khan, A. Q. Assessment of farmers on their knowledge regarding pesticide usage and biosafety. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 26, 1903–1910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2019.03.001 (2019).

Sapbamrer, R. & Nata, S. Health symptoms related to pesticide exposure and agricultural tasks among rice farmers from northern Thailand. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 19, 12–20 (2014).

Lekei, E. E., Ngowi, A. V. & London, L. Farmers’ knowledge, practices and injuries associated with pesticide exposure in rural farming villages in Tanzania. BMC Public Health 14, 1–13 (2014).

Yarpuz-Bozdogan, N. & Bozdogan, A. Pesticide exposure risk on occupational health in herbicide application. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 25, 3720–3727 (2016).

Tudi, M. et al. Exposure routes and health risks associated with pesticide application. Toxics 10, 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics10060335 (2022).

Tsakiris, P., Damalas, C. A. & Koutroubas, S. D. Safety behavior in pesticide use among farmers of northern Greece: The role of information sources. Pest Manag. Sci. 79, 4335–4342 (2023).

Khanal, G. & Singh, A. Patterns of pesticide use and associated factors among the commercial farmers of Chitwan, Nepal. Environ. Health Insights 10, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4137/ehi.s40973 (2016).

Damalas, C. A., Koutroubas, S. D. & Abdollahzadeh, G. Drivers of personal safety in agriculture: A case study with pesticide operators. Agriculture 9, 34 (2019).

Mequanint, C. et al. Practice towards pesticide handling, storage and its associated factors among farmers working in irrigations in Gondar town, Ethiopia, 2019. BMC. Res. Notes 12, 709. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-019-4754-6 (2019).

Taghdisi, M. H., Amiri Besheli, B., Dehdari, T. & Khalili, F. Knowledge and practices of safe use of pesticides among a group of farmers in Northern Iran. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 10, 66–72 (2019).

Sharifzadeh, M. S., Abdollahzadeh, G., Damalas, C. A., Rezaei, R. & Ahmadyousefi, M. Determinants of pesticide safety behavior among Iranian rice farmers. Sci. Total Environ. 651, 2953–2960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.179 (2019).

Sapbamrer, R. & Thammachai, A. Factors affecting use of personal protective equipment and pesticide safety practices: A systematic review. Environ. Res. 185, 109444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.109444 (2020).

Damalas, C. A. & Koutroubas, S. D. Vol. 4 1 (MDPI, 2016).

Okoffo, E. D., Mensah, M. & Fosu-Mensah, B. Y. Pesticides exposure and the use of personal protective equipment by cocoa farmers in Ghana. Environ. Syst. Res. 5, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40068-016-0068-z (2016).

Raimi, M., Muhammad, I. & Udensi, L. Assessment of safety practices and farmers behaviors adopted when handling pesticides in rural Kano state, Nigeria. Arts Humanit. Open Access J. 4, 191–201. https://doi.org/10.15406/ahoaj.2020.04.00170 (2020).

Memon, Q. U. A. et al. Health problems from pesticide exposure and personal protective measures among women cotton workers in southern Pakistan. Sci. Total Environ. 685, 659–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.173 (2019).

Bagheri, A., Emami, N. & Damalas, C. A. Farmers’ behavior towards safe pesticide handling: An analysis with the theory of planned behavior. Sci. Total Environ. 751, 141709 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Student Research Committee of Khalkhal University of Medical Sciences for providing financial support (Ethics Code: IR.KHALUMS.REC.1401.011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Esmail Najafi: Supervision; Writing—review and editing; Narges Khanjani: Methodology and reviewing; Saeed Parastar: Formal analysis; Writing—original draft; Behnam Azizi Shalke: Collected data; Methodology; Yasamin Fathzadeh: Collected data; Methodology; Shahram Nazari: Conceptualization, Methodology; Esrafil Asgari: Writing—review and editing, Methodology; Hossein Najafi Saleh: Investigation, Writing—original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Najafi, E., Khanjani, N., Parastar, S. et al. Assessment of pesticide handling and use practices and associated health and safety concerns among rice farmers, in Northern Iran. Sci Rep 15, 25303 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09624-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09624-5