Abstract

This study introduces a novel Adaptive EWMA (AEWMA) control chart designed to monitor the mean of a normally distributed process with enhanced responsiveness. The proposed methodology dynamically adjusts the smoothing constant based on a proposed continuous function of the estimated mean shift derived from the EWMA statistic. The Monte Carlo simulations are conducted to assess the performance of the AEWMA chart across various magnitudes of process mean shifts, using run-length profiles as the primary evaluation metric. The results indicate that the AEWMA chart outperforms traditional methods in terms of detection efficiency. To demonstrate its practical applicability, the AEWMA chart is applied to a real-world manufacturing dataset, specifically analyzing the flow width resistance of substrates. The findings highlight the efficiency of the proposed chart, making it a valuable tool for improving process monitoring and quality control in industrial environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A control chart is an important statistical process control (SPC) tool because of its simplicity, efficiency, and capability to control process changes. They help uncover special cause variations within production processes that increase workforce productivity and quality. CCs are broadly categorized into two types: memory-less and memory-based. Compared to historical data, a Memory-less chart only utilizes the latest sample data to control the parameters of the process, shedding off the historical data that can be quite sensitive to minor alterations in the continual process. On the other hand, memory-based charts work with the information from previous samples, which helps them recognize small and constant changes in the process, which makes them more suitable for maintaining quality. Originally known as W. A. Shewhart1, CCs have become vital assets in the current quality improvement practices that enable various industries to realize their operational objectives and deliver reliable products. CCs have a significant role in statistical control by pointing out that a process is out-of-control where changes occur so that appropriate adjustments for quality and efficiency can be made Jensen et al.2. These charts are sorted into the memory-less and memory-based types that meet the requirements of specific monitoring processes. Memory-less CCs, including Shewhart charts (\(\:\stackrel{-}{X}\), R, S, etc.), utilize the current sample as is currently practiced to control and enhance processes. However, they may be less sensitive to subtle changes in the processes that exist within a general framework. On the other hand, memory-based CCs such as CUSUM and EWMA charts, created by Page3 and Roberts4, provide greater sensitivity by incorporating historical data. The EWMA chart is a particularly robust control chart for detecting even small shifts compared to Shewhart charts, given its application in precision control. These methods enable fast interventions, which are critical in improving the quality and stability of the process across many industries. The EWMA statistic is remarkable in detecting small shifts in the process parameters, leading to tremendous interest among researchers and engineers. For a more detailed understanding, readers should refer to Lucas and Saccucci5, Lowry et al.6, and Zhao et al.7. Furthermore, new developments and localized adaptations of these charts, designed for particular changes, are explained and reviewed in detail in the studies conducted by Noor-ul-Amin et al.8 and Riaz et al.9. CCs are efficient when the shift size is known before the analysis or when only a specific segment is of interest but encounter limitations when the shift in magnitude is unknown before the analysis. Researchers have suggested different forms of adaptive schemes, such as the AEWMA chart. The AEWMA combines the strengths of Shewhart and EWMA charts by dynamically adjusting the weight of previous observations based on error size \({e_t}={y_t} - {x_{t - 1}}\). This approach improves the detection of varying shift sizes while reducing the inertia problem, offering a more versatile solution for quality control. Capizzi and Masarotto10 introduced a comparative approach, recommending an AEWMA CC for monitoring the process average. They employed the Huber score function, which effectively integrates the strengths of EWMA and Shewhart charts, in the design of the AEWMA chart. Their study demonstrated that AEWMA charts outperform traditional Shewhart, optimal EWMA, Shewhart-EWMA, and optimal CUSUM charts in detecting mean shifts of varying sizes. Zhao et al.7 proposed a data-driven adaptive threshold algorithm combined with the EWMA method to dynamically monitor voltage differences in energy storage systems. The approach improves early warning accuracy, achieving false alarm and omission rates below 1%, while reducing operational workload and enhancing system safety and reliability. Abubakar et al.11 derived analytical formulae using the Markov chain method for computing ATS in the EWMA CCC chart. They introduced a VSI EWMA CCC chart to improve sensitivity in high-yield processes. The VSI EWMA CCC chart outperforms existing methods in out-of-control detection, with practical implementation demonstrated through an injection molding example. Liu et al.12 proposed two one-sided CCs, HEWMA1 and HEWMA2, for monitoring shifts in process variance by integrating two EWMA statistics. Their performance was evaluated using Monte Carlo simulations based on ARL, SDRL, and median run length. Additional metrics like EQL, RARL, and PCI were used for comprehensive comparison. Results showed that HEWMA1 and HEWMA2 outperform existing charts, and their effectiveness was validated using real industrial data. Noor-ul-Amin and Noor13 proposed a new AEWMA CC in Bayesian theory, utilizing conjugate priors under squared error and linex loss functions to monitor the process mean. A comparative analysis and Monte Carlo simulations demonstrated its superior performance over the existing Bayesian EWMA chart, supported by a real-data example for practical implementation. Noor-ul-Amin et al.14 proposes an AEWMA CC based on support vector regression (SVR) to monitor process dispersion. It evaluates different SVR kernels—linear, polynomial, and RBF—and adapts the smoothing constant based on shift size. Results using real-life data show the RBF-based SVR-AEWMA chart effectively detects dispersion shifts with high adaptability and reliability. Kazmi et al.15 presents an SVR-based AEWMA CC for improved monitoring of process mean shifts. It compares linear, polynomial, and RBF kernels, highlighting the RBF kernel’s superior performance. Real-life data application confirms the chart’s adaptability and reliability in detecting location shifts. Ahmadini et al.16 proposes a risk-adaptive EWMA CC based on residuals from an artificial neural network to monitor patient safety in hospitals. Applied to cardiothoracic surgery data, the chart effectively detects shifts in patient risk. Results show it outperforms traditional risk-adjusted EWMA charts, supporting improved healthcare quality. Zaman and Khan17 introduces an adaptive CUSUM CC enhanced by SVR to dynamically adjust parameters based on process conditions and shift magnitudes. Performance evaluation using ARL and SDRL, supported by Monte Carlo simulations, shows superior detection compared to existing charts. Real-life manufacturing data further validates the chart’s practical effectiveness and efficiency. Sarwar and Noor-ul-Amin18 introduced a memory-based AEWMA CC (AEWMA-I) designed for monitoring the mean of a normally distributed process. The chart estimates mean shifts using an EWMA statistic and determines the smoothing constant through a continuous function. Monte Carlo simulations demonstrate its superior efficiency compared to competing charts across various mean shifts. The practical application of the AEWMA-I chart is illustrated using real manufacturing data on substrate flow width resistance.

Haq et al.19 introduced the AEWMA-II chart, employing a novel methodology to monitor the process mean. Their approach used a bias-free estimator to determine the mean shift and a step function to select the smoothing constant for plotting the EWMA statistic. Building on this, we propose an improved AEWMA CC to monitor the mean of a normally distributed process. This enhanced chart first employs the EWMA statistic alongside an estimator for the mean shift. Then, the smoothing constant is calculated using a proposed continuous function that adapts based on the size of the estimated shift. To evaluate the performance of the proposed chart, zero-state run-length (RL) profiles are computed through Monte Carlo simulations. Metrics relating to the quality of vibration monitoring involve average run length (ARL) and standard deviation of RL (SDRL) to offer a comprehensive analysis. Haq et al.19 have shown that using the AEWMA-I chart is superior to other methods, including the EWMA chart, AEWMA chart, CUSUM chart, ACUSUM chart, and DCUSUM chart. As a result, the comparison targets solely the AEWMA-I and AEWMA-II charts to showcase and deliberate on developing our proposed method.

The motivation of the proposed AEWMA CC is based on the flaws of the adaptive function used in the AEWMA-II chart described by Haq et al.19. More precisely, the discrete characteristic of the smoothing constant in these methods results in irregular ARLs and an increased probability of false alarms, hence its weakness. To counter these limitations, we propose the AEWMA CC, which includes a continuous adaptive process function. It should be noted that this approach not only improves the performance of the ARL but also solves the problem of many false alarms. In practice, it is not necessary to identify the entire process shift, and the range of this shift can differ. Thus, it is appropriate to consider shift size as a random variable and estimate it using a suitable statistic. In the proposed AEWMA CC, the shift size is first estimated, and then the smoothing constant’s value is found using the proposed continuous adaptive function. This increases its power and effectiveness for process monitoring in various applications by enhancing the chart’s efficiency in detecting shifts of all sorts of dimensions with this methodology. The structure of the paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 presents a detailed description of the suggested AEWMA-III CC for monitoring the location parameter of a process. Section 3 described the performance evaluation and discussion, while Sect. 4 described the application of the chart using a real-life dataset. The conclusion is presented in Sect. 5 and Sect. 6 includes the future recommendations.

Design of the suggested AEWMA-III control chart

In this section, we present a novel AEWMA-III CC designed to track variations in the process mean of a normally distributed process. Consider a sequence of independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) random variables {Yt}, each having a normal distribution with a mean and variance 2 at time ≥ 1. Initially, the process is assumed to be in an in-control (IC) state for ≤ 0. Beyond this point ( > 0), the process shifts to an out-of-control (OOC) state due to an unknown change in the mean, denoted as 1. When the process transitions to the OOC state, the distribution changes to Xt∼N(δ,1), where shift δ=|µ1-µ|⁄σ. This standardization provides a framework for efficiently monitoring process changes and detecting shifts in the mean.

Let \(\:\widehat{{\delta\:}_{t}}\) represent the estimated mean shift at time . According to the shift estimator offered by Jiang et al.20, it is defined as follows:

The smoothing constant is denoted as ψ∈ (0,1], with the initial estimate set to \(\:{\widehat{\delta\:}}_{0}^{*}=0\). The estimator is unbiased under the IC process state but exhibits bias in the OOC. To address this limitation, Haq et al.19 proposed an improved estimator that remains unbiased in both IC and OOC states, expressed as follows:

For estimating δ, it is offered to utilize \(\:{\widehat{\delta\:}}_{t}=\left|{\widehat{\delta\:}}_{t}^{**}\right|\).

The plotting statistic for the suggested AEWMA-III chart, based on the sequence \(\:\left\{{X}_{t}\right\}\), used for monitoring the process mean is defined as:

where \(\:{V}_{0}=0\) and \(\:g\left({\widehat{\delta\:}}_{t}\right)\in\:\left(\text{0,1}\right]\) such that

Where the k = 2 and xo = 1.25. The more details is given in appendix A.

Decision rule. In the one-sided proposed AEWMA CC, an OOC signal is triggered when the proposed statistic ∣Vt∣ exceeds the specified threshold ℎ. For the two-sided AEWMA CC, the process is considered OOC if the proposed statistic V either exceeds ℎ or falls below −ℎ. This mechanism ensures robust monitoring of process deviations for single-direction and dual-direction shifts. The threshold value ℎ (always positive, ℎ > 0) is a critical parameter in the control chart. It is determined to ensure that the in-control ARL, denoted as 0, remains at a predefined level. The value of ℎ is computed individually for each specified combination of the smoothing parameter , allowing for precise calibration of the control chart under varying process conditions.

Performance evaluation and discussion

The effectiveness of any CC is evaluated using RL characteristics, such as the mean and standard deviation of the RL. These metrics provide crucial insights into the chart’s ability to detect process shifts accurately. Several methodologies are available for calculating RL attributes, including the Probability method, Markov chain analysis, Integral equations, and MC simulation (cf. Abbasi et al.21; Abid et al.22; Abbas et al.23; Zaman et al.24; Abid et al.25; Sherwani et al.26; Abbas et al.27; Javed et al.28). We employed the MC simulation method for this study due to its extensive application and reliability in performance evaluation. The RL profiles for the proposed AEWMA-III CC were derived using estimates from samples that follow a normal distribution with mean and variance of 1. The mean shift parameter was set at predefined levels: =0.00, 0.25, 0.50, 0.75, 1.0, 1.50, 2.0, 2.50, 3.50, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0 To have a better understanding of chart behavior in both IC and OOC.

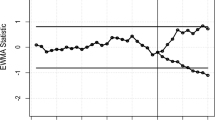

For the in-control A0, fixed values of 0 = 100, 370, and 500 were used. Furthermore, the smoothing constant is being looked at in = 0.10, 0.15, and 0.20 to study the characteristics of different parameter settings of the chart. This systematic design provides a comprehensive and comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of the AEWMA-III CC across various situations to demonstrate its ability to identify shifts in the process. This is evident from the analysis of ARL and SDRL in terms of zero-state perspective, where the proposed AEWMA-III CC surpasses all other profiles for our chosen range of process mean shift . The chart further illustrates improved sensitivity and reliability in identifying incremental changes and fluctuations in large magnitudes and reduced variability in flagging OOC conditions. Comparisons of its performance with other methods are shown in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4. It improved accuracy in process, product monitoring, and quality control. The literature in the domain of SPC has extensively analyzed adaptive charts and appreciated their enhanced sensitivity compared to the non-adaptive CCs when it comes to detecting the shift inside a specific range. This increased sensitivity gives improved protection against variations within the specific process. Haq et al.19 suggested AEWMA-II CC that utilized a bias-free estimator for monitoring shifts and used a step function to determine the smoothing constant for the EWMA statistic. Their analysis claimed that the AEWMA-II chart outperforms existing CC, including the AEWMA, CUSUM, ACUSUM, and DCUSUM charts. A comparative analysis was conducted against the AEWMA-II chart to evaluate the offered AEWMA-II chart. The RL profiles for both charts were computed using MC simulations with 100,000 iterations, providing robust performance metrics. As shown in Table 1, the proposed AEWMA-III control chart demonstrates superior performance compared to the AEWMA-II chart across various values ψ of ARL0 = 100, 370, and 500. For instance, at ψ = 0.10,0.15, and 0.20 with δ = 0.50 and ARL0 = 370, the proposed AEWMA-III chart achieves ARL = 17.73, 20.78 and 22.37, respectively, whereas the AEWMA-II chart records ARL = 19.49, 21.67, and 24.31. Similarly, for δ = 1.50, the proposed AEWMA-III chart yields ARL = 2.08,2.20, and 2.33, outperforming the AEWMA-II chart, which reports ARL = 2.35,2.65, and 2.94. This trend is consistent across various shift sizes, indicating that the proposed AEWMA-III chart significantly better results for moderate and large shift sizes, further validating its effectiveness in process monitoring and quality control. Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4 clearly illustrate that the proposed AEWMA-III CC outperforms the AEWMA-I and AEWMA-II charts, particularly for moderate and large process shifts. The calculated ARL values underscore the superior performance of the AEWMA-III chart, demonstrating its effectiveness in detecting shifts more efficiently. Implementing the proposed AEWMA-III chart in industrial processes provides a significant advantage by timely identifying deviations, preventing potential adverse outcomes and enhancing overall process stability and reliability. The following are the main points.

-

Table 2 reveals a clear trend where ARL1 values decrease as the shift magnitude increases. For instance, with 0 = 370, = 3, and = 0.15 1 is 2.38 at =1.0 but decreases significantly to 1.06 when = 1.50. Similarly, for 0 = 500, the corresponding 1 values decline from 2.40 at = 1.0 to 1.06 at =1.50. This demonstrates the increased efficiency of the chart in detecting larger shifts.

-

At fixed δ, the ARL tends to increase as the value of ψ increases and vice versa. For instance, from Tables 1, 2 and 3 with fixed δ = 0.75 at ψ = 0.15 and 0.20, the respective ARL1 = 2.97 and 3.23 at ARL0 = 370. The same pattern can be seen at ARL0 = 100 and 500.

-

Increasing sample sizes generally results in lower 1 values, indicating improved performance in detecting process shifts. For instance, with a shift () of 1.50, increasing the sample size from 3 to 5 reduces the 1 from 1.27 to 1.14 in most cases. This demonstrates that larger sample sizes enhance the CC’s efficiency in identifying out-of-control processes.

-

The proposed AEWMA-III charts consistently outperformed existing CCs across various conditions. Its superior performance is reflected in consistently lower ARL and SDRL values, demonstrating enhanced robustness and reliability. Furthermore, its adaptability to various scenarios underscores its versatility in effectively detecting and monitoring process shifts.

-

The sensitivity of a CC to moderate and large shifts can be enhanced by selecting a smaller value of , particularly when the variable under study necessitates a highly responsive monitoring system for detecting small shifts.

Illustrative example

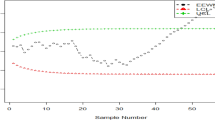

In SPC literature, evaluating and demonstrating the performance of CC using real and simulated datasets is a well-established practice. In this study, we utilize a real dataset to illustrate the implementation and effectiveness of the AEWMA-II and the proposed AEWMA-III charts. The dataset, sourced from Montgomery29, comprises 45 samples, each consisting of five wafers. The context of the dataset lies in semiconductor manufacturing, specifically in the photolithography process coupled with the hard bake process, where the objective is to statistically monitor and control the flow width of the resist. Flow width measurements are recorded in microns, with samples collected at one-hour intervals. The first 30 samples represent an in-control IC process (0 = 30) and constitute the phase-I dataset. The remaining 15 samples comprise an OOC process, forming the phase-II dataset. To simulate an upward shift in the process mean, all observations in the phase-II dataset are augmented by adding 0.017, representing a gradual deviation from the IC state. This setup provides a robust design for assessing the performance of the suggested CC in detecting process shifts.

Figures 5 and 6 presents the behavior of both CCs during the monitoring process. For the first 30 samples, both the suggested AEWMA-III and AEWMA-II CCs remain stable, which indicate that the process IC state with no significant deviations observed. while, for the remaining 15 samples, both charts begin to reflect an upward shift in the IC process mean, signaling a transition to an OOC state. A key observation is the superior sensitivity of the offered AEWMA-III chart compared to the AEWMA-II chart. In particular, executing the AEWMA-III chart yields an OOC signal at 37 sample while using the AEWMA-II chart yields an OOC signal at the 43rd sample. This demonstrates that the AEWMA-III chart offers a better capability of detecting the process shifts at an earlier time which is very useful in industries where early signal of shift is very important so as to avoid any buildup of disruption and maintain process quality. Thus, the results proved that the proposed AEWMA-III CC is more effective and responsive than the previous AEWMA-II CC, which provides practical improvement of the process monitoring system.

Conclusion

Adaptive CCs have been of great interest in the latest years due to their higher sensitivity than non-adaptive ones. We presented an improved AEWMA-III control chart for detecting occasional shifts in the mean of a normally distributed process. AWMA-II CC formulated by Haq et al.14 has established AEWMA, CUSUM, ACUSUM and DCUSUM charts in detecting shifts in the mean of normally distributed processes. Furthermore, the ARL properties of the proposed AEWMA-III CC are compared against different shift sizes using a comprehensive set of properties. It is shown that the new CC outperforms traditional methods in virtually all types of shifts but performs optimally in moderate and large magnitude shifts. A numerical example showcases its practical utility, illustrating the application of the proposed AEWMA-III CC using real-world data. The current methodology can be extended to develop AEWMA charts capable of monitoring process variance shifts or tracking mean and variance. Additionally, the approach can be adapted to design AEWMA charts for multivariate normally distributed processes or for processes that do not follow a normal distribution, broadening the scope and applicability of these CCs in diverse industrial scenarios.

Future recommendations

Future research can extend the proposed AEWMA-III CC in several directions to enhance its applicability and robustness. One potential avenue is to develop variants that monitor process variance or jointly track both mean and variance, enabling more comprehensive quality control. Additionally, designing a multivariate version would be valuable for processes involving multiple correlated variables. The method could also be adapted for non-normal distributions to improve its usability in broader industrial scenarios. Incorporating machine learning for real-time adjustment of the smoothing constant and exploring Bayesian frameworks to integrate prior knowledge are also promising directions. These advancements would further strengthen the adaptability and effectiveness of AEWMA-based CCs in modern quality monitoring systems.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The five wafers dataset, sourced from Montgomery [24], comprises 45 samples, which were used in study for practical importance of the proposal scheme of process monitoring.

Change history

16 October 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23526-6

References

Shewhart, W. A. The application of statistics as an aid in maintaining quality of a manufactured product. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 20 (152), 546–548 (1925).

Jensen, W. A., Bryce, G. R. & Reynolds, M. R. Jr Design issues for adaptive control charts. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 24 (4), 429–445 (2008).

Page, E. S. Continuous inspection schemes. Biometrika 41 (1/2), 100–115 (1954).

Roberts, S. Control chart tests based on geometric moving averages. Technometrics. 42 (1), 97–101. (1959).

Lucas, J. M. & Saccucci, M. S. Exponentially weighted moving average control schemes: properties and enhancements. Technometrics 32 (1), 1–12 (1990).

Lowry, C. A., Champ, C. W. & Woodall, W. H. The performance of control charts for monitoring process variation. Commun. Statistics-Simulation Comput. 24 (2), 409–437 (1995).

Zhao, J. et al. Dynamic Monitoring of Voltage Difference Fault in Energy Storage System Based on Adaptive Threshold Algorithm. 2020 IEEE 4th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), 2413–2418. (2020).

Noor-ul-Amin, M., Javaid, A., Hanif, M. & Dogu, E. Performance of maximum EWMA control chart in the presence of measurement error using auxiliary information. Communications Statistics-Simulation Computation, 1–25. (2020).

Riaz, M., Abbas, Z., Nazir, H. Z., Akhtar, N. & Abid, M. On designing a progressive EWMA structure for an efficient monitoring of silicate enactment in hard bake processes. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 46 (2), 1743–1760 (2021).

Capizzi, G. & Masarotto, G. An adaptive exponentially weighted moving average control chart. Technometrics 45 (3), 199–207 (2003).

Abubakar, S. S., Khoo, M. B. C., Saha, S. & Lee, M. H. A new exponentially weighted moving average chart with an adaptive control scheme for high yield processes—An application in injection molding process. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 37 (2), 527–540 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. New hybrid EWMA charts for efficient process dispersion monitoring with application in automobile industry. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 131 (2), 1171–1195 (2022).

Noor-ul‐Amin, M. & Noor, S. An adaptive EWMA control chart for monitoring the process mean in bayesian theory under different loss functions. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 37 (2), 804–819 (2021).

Noor-ul-Amin, M., Kazmi, M. W., Alkhalaf, S., Abdel-Khalek, S. & Nabi, M. Machine learning based parameter-free adaptive EWMA control chart to monitor process dispersion. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 31271 (2024).

Kazmi, M. W. & Noor-ul‐Amin, M. Adaptive EWMA control chart by using support vector regression. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 40 (7), 3831–3843 (2024).

Ahmadini, A. A., Abbas, T. & AlQadi, H. Adaptive EWMA control chart by adjusting the risk factors through artificial neural network. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 41 (3), 992–1001 (2025).

Zaman, B. & Khan, N. Adaptive CUSUM Control Chart Utilizing Supervised Learning for Monitoring the Process Location Parameter: A Case Study Application (Quality and Reliability Engineering International, 2025).

Sarwar, M. A. & Noor-ul‐Amin, M. Design of a new adaptive EWMA control chart. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 38 (7), 3422–3436 (2022).

Haq, A., Gulzar, R. & Khoo, M. B. C. An efficient adaptive EWMA control chart for monitoring the process mean. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 34 (4), 563–571 (2018).

Jiang, W., Shu, L. & Apley, D. W. Adaptive CUSUM procedures with EWMA-based shift estimators. IIE Trans. 40 (10), 992–1003 (2008).

Abbasi, S. A., Abbas, T. & Adegoke, N. A. Improved Simple Linear Profiling Methods with Application to Chemical Gas Sensors. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 37 (8), 3179–3191. (2021).

Abid, M., Nazir, H. Z., Muhammad, T., Riaz, M. & Abbas, T. A comparative analysis of robust dispersion control charts with application related to health care data. J. Test. Eval. 28 (1), 247–259 (2020).

Abbas, T., Riaz, M., Javed, B. & Abujiya, M. R. A new scheme of dispersion charts based on neoteric ranked set sampling. Aims Math. 8 (8), 17996–18020 (2023).

Zaman, B., Nazir, H. Z., Khan, N., Riaz, M. & Abbas, T. Corrections to an adaptive EWMA control chart based on Hampel function to monitor the process location parameter. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 40 (1), 752–757 (2024).

Abid, M., Sun, M., Shabbir, A., Bakr, M. E. & Abbas, T. An enhanced non-parametric quality control chart with application related to industrial process. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 13561 (2024).

Sherwani, R. A. K., Qasim, H., Abbas, S., Abbas, T. & Aslam, M. Performance evaluation of DEWMA3 in phase-II for capturing changes in simple linear profiles based on run rule mechanism. Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 8609 (2023).

Abbas, T., Javed, A. & Abbas, N. Bayesian enhanced EWMA scheme for shape parameter surveillance in inverse Gaussian models. Comput. Ind. Eng. 197 (2024), 110637. (2024).

Javed, A., Abbas, T., Abbas, N. & Riaz, M. Designing bayesian paradigm-based CUSUM scheme for monitoring shape parameter of the inverse Gaussian distribution. Computers Industrial Eng. 192 (2024), 110235 (2024).

Montgomery, D. C. Introduction to Statistical Quality Control (Wiley, 2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, KSA, for funding this research work through the project number NBU-FFR-2025-2230-02.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.A., T.A., and A.A.H.A. contributed to drafting the original manuscript, conducting mathematical analyses, and performing numerical simulations. W.A. and B.A. conceptualized the core research problem and carried out the data analysis. T.A. and W.A. rigorously validated the results, restructured the manuscript, and supervised the funding acquisition. B.A. and A.A.H.A. further enhanced the manuscript’s language and contributed to additional simulation work. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, Walid Abdelfattah was omitted as a corresponding author. Correspondence and requests for materials should also be addressed to walid.abdelfattah@nbu.edu.sa.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

AlQadi, H., Abdelfattah, W., Abbas, T. et al. Design of an EWMA control chart by adaptation of smoothing constant based on a function of estimated shift. Sci Rep 15, 24730 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09735-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09735-z