Abstract

Accurately predicting losses resulting from traffic accidents holds crucial significance for accident prevention. Traffic accident forecasting faces challenges. For example, traffic accident forecasting models often exhibit suboptimal accuracy. In this study, these challenges are addressed by integrating the autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model with the backpropagation (BP) neural network model. Through parameter tuning and model optimization, the predictive accuracy of traffic accident losses is effectively improved, providing more precise forecasting results for accident prevention. Furthermore, a single model may not adequately explore the intricate nonlinear relationships involved due to the complex causal mechanisms of traffic accidents. To address this issue, neural networks are combined with the ARIMA model, and the impact of nonlinear factors in traffic accidents is fully considered. The ARIMA-BP forecasting method is applied to predict the number of traffic accidents, fatalities, injuries, and property damage in China. The results indicate that during the forecast period from 2016 to 2020, the average annual error rates of the ARIMA-BP model for the number of accidents, number of fatalities, number of injuries, and property damage are 4.16%, 3.67%, 7.45%, and 5.94%, with an average prediction error rate of 5.31%. The ARIMA-BP model demonstrated 2.61% and 6.24% lower error rates than the ARIMA model and BP neural network, respectively. The ARIMA-BP model exhibited lower average annual error rates than the individual models. This study substantiates the effectiveness and superiority of the ARIMA-BP prediction model in predicting traffic accident losses, providing a more efficient tool and theoretical basis for assessing and preventing traffic accident risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Literature review

Traffic accident prediction involves refining and analyzing traffic accident data to understand the fundamental evolution patterns of accidents. Models are utilized to speculate or calculate potential future scenarios based on insights and accident development analyses. Numerous factors contribute to traffic accidents, including driver errors, mechanical malfunctions, weather conditions, fatigue, and poor road conditions1. Analyzing the influencing factors and primary causes of road traffic accidents allows for predicting future trends, aiming to reduce the quantity and severity of accidents2. Currently, widely used methods for traffic accident prediction include time series analysis3, regression analysis4, gray prediction5, Bayesian network prediction6, random forest method7, neural network models8, and combination method9,10. This study provides a literature review of domestic and international studies concerning time series and neural network-based traffic accident prediction models and combined prediction models.

Time series analysis is a commonly employed method in accident prediction due to its broad applicability and high interpretability. This method captures time-related patterns such as trends, seasonality, and cycles by considering the temporal dependencies between data points. Miller (2018) utilized the autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) method to predict monthly transportation prices, demonstrating close estimations to observed data and effectively reflecting industry dynamics11. Van et al. (1996) applied a hybrid method for short-term traffic forecasting. This method exhibited strong transferability12. Zhang et al. (2022) combined time series prediction with neural networks, emphasizing the significance of predicting traffic flow time series data for urban traffic planning and management13. However, time series methods have limitations, requiring sufficient historical data for accurate predictions, and may overfit historical data, leading to poor performance on new data, especially in the presence of nonlinear relationships or external interference.

As powerful machine learning methods, neural network models are versatile in various prediction scenarios. These models excel at learning and capturing nonlinear relationships within complex data patterns and structures. Abojaradeh (2015) employed the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) to establish a statistical regression model to predict accident rates based on driver behavior mistakes14. Xu et al. (2020) tested the performance of different classifiers and found that deep neural networks (DNNs) performed the best among their peers, improving accident analysis and prevention15. Ye et al. (2023) introduced a novel data-driven traffic accident prediction decision model. This model’s effectiveness was validated using traffic management data from 31 Chinese provinces from 2003 to 202016. Wu et al. (2023) experimentally proved the superiority of the multi-attention dynamic graph convolution network (MADGCN). The MADGCN achieved F1-score improvements of 11.61% and 9.15% compared to the F1-scores of existing methods on two real traffic accident datasets17. Gorzelanczyk (2023) utilized neural network methods to predict accident numbers in various provinces of Poland, minimizing the mean absolute error and mean absolute percentage error through weight adjustments. This study also revealed limitations in neural network prediction methods, particularly their ability to extract seasonal information effectively18. Zhan et al. (2023) constructed a neural network model based on multilayer perceptron (MLP) and optimized it using a backpropagation algorithm to improve reserve upgrade prediction accuracy and reliability19. The prediction accuracy of the constructed neural network model can reach over 90%. Yang et al. (2022) achieved a comprehensive and accurate analysis of the severity of traffic accidents through multitasking and deep learning design, addressing the lack of interpretability of deep neural networks (DNNs) in existing research20. Zargari (2022) studies the critical role of travel time reliability in passenger selection and freight transportation, pointing out the impact of factors such as traffic flow, accidents, and adverse weather on travel time21. The results showed that the introduction of GA not only improved the stability of the model, but also reduced prediction errors. Meanwhile, sensitivity analysis explored the response of the planning time index to independent variable fluctuations.

Jiang and Luo (2022) discussed the challenges in traffic prediction, emphasizing the involvement of spatiotemporal data and external factors such as time, weather conditions, and driver habits. They highlighted the difficulty in integrating heterogeneous data as an unresolved issue in predictive research22. Tian and Zhang (2022) proposed a deep learning framework incorporating spatiotemporal attention mechanisms to address urban traffic accident prediction23. The current deep learning models in traffic flow prediction studies are often considered “black box models.” Therefore, the interpretability and visualization of deep learning models for traffic accident prediction are identified as future research directions. In summary, neural network models have certain limitations. These models typically require large amounts of labeled data for training, which may be challenging to obtain in certain domains. In addition, tuning numerous hyperparameters, including the network structure and learning rate, requires careful optimization. Additionally, neural network models operate as black-box models, making interpreting their decision-making processes challenging.

To overcome the limitations of single models and enhance predictive performance, scholars worldwide have conducted in-depth research on ensemble prediction for accidents. Sawalha and Sayed (2006) proposed a method to recalibrate a negative binomial accident model before transferring it to different time and space regions, achieving better performance than that of a model based on a random forest24. Lin et al. (2015) introduced a variable selection method based on the frequent pattern tree (FP tree), outperforming a model based on a random forest25. Yasin and Tortum (2015) utilized an artificial neural network (ANN) to predict accidents on the Erzurum highway in Turkey, emphasizing the importance of the vertical curvature degree26. Yannis et al. (2017) evaluated existing models based on theoretical approaches, model features, implementation conditions, data requirements, and existing results27. Lin et al. (2021) established accident risk prediction models using naive Bayes, decision trees, Bayesian networks, and multilayer perceptrons (MLPs), identifying critical risk factors28. Ma et al. (2021) proposed a prediction model for traffic accident severity based on a single-stage autoencoder (SSAE) and achieved better performance than that of other models29. Hu (2021) found that the Bayesian neural network (BNN) outperformed other models in regression prediction based on a comparison of the mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE)30. Guo et al. (2022) utilized a gray model (GM) to obtain predicted data and then trained a backpropagation (BP) neural network and demonstrated the superior accuracy of the GM-BP prediction model over that of the GM model31. Zheng and Wu (2015) introduced a combination prediction model based on the induced ordered weighted geometric average (IOWGA) operator32. This model integrates the GM(1,1) and Verhulst models, incorporating variable weight coefficients for each model. The authors proposed a combination model based on the optimal weighting (OW) method for comparison. The results indicated that the combined model outperformed the other three models, thus, effectively leveraging various models’ advantages. Bates and Grangeret (1969) proposed the concept of combination forecasting in 196933. This approach involves appropriately combining the results of various forecasting methods to achieve optimal prediction results with higher accuracy compared with those of individual methods. Zhang (2003) applied a combination prediction model to sunspot prediction, achieving favorable predictive outcomes34.

The key to predicting traffic accident losses lies in selecting indicators and using suitable prediction models. Optimizing and improving the prediction model can help enhance the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the prediction. At present, there are mainly the following problems in the research of traffic accident loss prediction: (1) incomplete data. The prediction methods for traffic accident losses usually rely on historical traffic accident data, and the comprehensiveness and accuracy of the data are crucial for prediction research35. Research on traffic accident losses is limited by limited data sources and missing statistical data, resulting in insufficient data integrity. When predicting accident losses, the indicators measured are often too single to fully explain the severity of the accident losses. (2) The applicability of the traffic accident loss model is poor. Among numerous accident loss prediction models, traditional prediction models generally rely on overall historical data for prediction, while ignoring the specific influencing factors of accidents, such as road conditions and transportation-related factors. These characteristic factors related to traffic accident losses are also of great significance for the accurate prediction of the Model36. In recent years, machine learning prediction models, such as neural network models, have been widely used in the field of traffic accident loss prediction. Due to their strong nonlinear mapping ability to traffic accident data, they continuously adjust and approximate the optimal results through training on a large amount of data, making them widely used. Selecting an appropriate model is crucial for improving accuracy and ensuring prediction comprehensiveness in the prediction process37.

In addition to the transportation field, accident prediction methods and models are also widely used in other fields. Dey et al. (2023) predicted the annual gasoline demand in India38. Han et al. (2023) provided a combination prediction method by integrating linear and nonlinear elements, providing information for balanced production strategies39. Lwaho and Ilembo (2023) established a model for predicting maize yield in Tanzania using the ARIMA model40. Mati et al. (2023) studied the performance of different prediction models in predicting global economic indicators and the impact of incorporating war information in the prediction process on prediction accuracy41. Wen et al. (2023) proposed a carbon emission prediction model based on the inverse error combination method for the linear and nonlinear relationship of carbon emission data42. In practical applications, no single model or method can universally apply to all predictive scenarios43. Therefore, it is crucial to choose suitable models and methods for predictions. The studies above indicate that ensemble prediction models possess advantages not found in single predictive models and show promising application prospects. The integration of ARIMA, which is effective in extracting linear information from time series44]– [45, and BP neural networks, which are capable of handling complex nonlinear relationships in data45]– [46, is mainly explored in this paper.

A systematic review of hybrid ARIMA-neural network methodologies reveals several established integration approaches in time series prediction. Traditional hybrid methods typically employ two main combination strategies: direct addition and weighted integration. The direct addition approach, as demonstrated by Lu (2021) in GDP forecasting, simply combines the predicted values from ARIMA and BP models, achieving a relative error reduction to 1.5% compared to single models47. The weighted integration method, exemplified by Wang (2022) in coal consumption prediction, constructs multiple linear regression using ARIMA’s linear fitting and BP’s nonlinear fitting as independent variables, improving prediction accuracy with fitting errors below 0.62%48. Recent advances in hybrid modeling have introduced more sophisticated integration frameworks. For instance, Hou and Chen (2024) proposed incorporating feature selection through Lasso regression before combining ARIMA and BPNN for carbon emission prediction, demonstrating enhanced model stability and reliability49.

However, these conventional hybrid approaches face limitations when applied to complex traffic accident prediction scenarios. First, simple additive or weighted combinations often fail to capture the intricate causal mechanisms underlying traffic accidents, as they treat the integration process as a static combination rather than a dynamic interaction. Second, existing hybrid models typically focus on single-target prediction, whereas traffic accident forecasting requires simultaneous prediction of multiple correlated targets (accidents, fatalities, injuries, and property damage). Third, most current approaches lack the capability to incorporate domain-specific risk factors and their hierarchical relationships into the model architecture. These limitations highlight the need for a more sophisticated integration framework specifically tailored to traffic accident prediction.

This study seeks to comprehensively understand the factors influencing traffic accidents and establish prediction models using ARIMA and BP neural networks. By combining the strengths of both models through the ARIMA-BP model, the study aims to achieve more accurate predictions. A comparative analysis of the accuracy and effectiveness of single and ARIMA-BP models is conducted using the same accident dataset and prediction periods. The goal is to determine the optimal model for traffic accident loss prediction, providing valuable references for safety management and sustainable development in the transportation industry. The ARIMA-BP combination is based on the specific needs of traffic accident prediction, which involves both linear and nonlinear components. While ARIMA-SVM effectively handles nonlinear data, it may overfit when dealing with complex, high-dimensional datasets. ARIMA-LSTM combination captures long-term dependencies but requires extensive data and is computationally intensive. In contrast, ARIMA-BP strikes a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. It handles both linear and nonlinear patterns effectively without excessive complexity, making it particularly advantageous for medium-scale datasets and real-time prediction needs50.

The key innovation of the study lies in the tailored integration of the ARIMA and BP neural network models specifically for traffic accident prediction. While both models have been used separately in various domains, our approach uniquely combines them sequentially, where the ARIMA model addresses linear trends, and the BP neural network captures residual nonlinearities. This integration, along with the use of residual optimization, enhances prediction accuracy by effectively modeling the complex, multi-faceted nature of traffic accident data. Additionally, our application of this hybrid method to traffic safety prediction, with a focus on minimizing prediction errors and improving model stability, represents a novel contribution to the field. This comprehensive approach has not been extensively explored in traffic accident prediction, offering new insights and practical benefits for safety management. The novelty of accident prediction research lies in its use of technological means to enhance the foresight of preparation work, the accuracy of planning work, and the initiative of hazard investigation. These innovations are all based on modern data analysis and artificial intelligence technologies, which enable predictions to no longer be limited to static historical data, but to dynamically and real-time respond to potential risks.

Traffic accident risk analysis

In previous studies on traffic accident prediction, there has been limited systematic analysis of traffic accident risk. Analyzing the factors influencing traffic accidents is crucial for selecting indicators and choosing accident prediction models. In reviewing the literature and analyzing road traffic accident cases, Vensim System Dynamics software was employed to conduct a risk analysis based on people, vehicles, traffic environments, and traffic systems. Figure 1 illustrates the causal flowchart of the traffic risk system analysis, which includes three levels: risk analysis based on people, risk analysis based on vehicles, and risk analysis based on traffic environments.

In analyzing the risk system based on people, both pedestrian and driver risks impact the overall risk to individuals, with driver factors being the primary cause of traffic accidents. Factors such as drivers’ poor psychological and mental states, inadequate driving experience and skills, and traffic regulation violations can increase driver risk, thereby elevating the overall risk to individuals. Pedestrian risk increases when there is a lack of pedestrian safety awareness and protective equipment and when pedestrians violate traffic rules, resulting in an overall increase in risk to individuals. In analyzing the risk system based on vehicles, vehicle risk is influenced by factors such as vehicle performance, operational conditions, auxiliary driving systems, and environmental impacts. A vehicle’s power and braking system performance significantly affects its overall performance. Poor performance in these systems can increase the risk associated with the vehicle. Factors such as high speed and excessive acceleration can destabilize vehicle operations, leading to an increased risk. Brake assistance and braking systems can effectively help reduce vehicle risk. Environmental factors such as traffic congestion and road conditions also impact vehicle risk. In analyzing the risk system based on traffic environments, road design elements such as the road segment length, curvature, and slope affect environmental risk. Factors such as excessively large curvatures and steep slopes can increase environmental risk. Road surface conditions, including smoothness and the presence of pits and grooves, also affect environmental risk. The absence of road safety facilities, such as road signs, markings, lighting, and road indicator lights, can increase environmental risk. Adverse weather conditions, such as rain, snow, fog, or poor visibility, can further increase environmental risk during driving.

The causal relationship is obtained based on the mechanism of actual traffic accidents and analysis of past traffic accident cases. A risk analysis diagram for the road traffic system is obtained by analyzing the causal flow of risks in a road traffic system. This diagram reflects the evolutionary process of safety risks in driving, where various factors, such as vehicle risk, pedestrian risk, and road environment risk influence the road traffic system risk. Therefore, in traffic accident loss prediction, it is necessary not only to consider the patterns and trends of accident data but also to focus on the impact of factors related to traffic accidents on predictions. It is crucial to comprehensively consider the dual influence of historical accident data and accident impact indicators and ultimately select an appropriate predictive model.

Model construction and data preprocessing

Section “Construction of the Combined ARIMA-BP Model” introduces the model construction methods employed in the research on traffic accident prediction, including the theoretical formulas and modeling procedures for the ARIMA, BP, and ARIMA-BP models. Section “Data sources and collection” presents the source and statistical results of the traffic accident data used in the study, as well as the selection criteria for accident indicators, laying the foundation for subsequent data fitting and model prediction.

Construction of the combined ARIMA-BP model

The ARIMA model is a time series forecasting analysis method that is also known as the integrated moving average autoregressive model51. Differencing is a crucial step in the ARIMA model. In the time series ARIMA(p, d, q) model, p is the order of the autoregressive terms, q is the order of the moving average terms, and d is the differencing order needed to transform a nonstationary series into a stationary series. In the ARIMA model, the future values of the sequence are expressed as a linear function of the current and lagged terms of the lag and random disturbance terms. The general form of the model is shown in Eq. (1):

The modeling process of the ARIMA model can be divided into four key steps:

Step 1: Time Series Stationarity Test. Conducting a stationarity test is a fundamental step in time series analysis. This test ensures that the data meets the assumptions of the ARIMA model, which is crucial for enhancing the model’s accuracy and predictive performance. If the data is nonstationary, it is typically stabilized through techniques such as differencing, de-trending, or logarithmic transformation. Step 2: Model Order Determination. This step involves selecting the appropriate order of the ARIMA model components (autoregressive, differencing, and moving average) based on the data characteristics and model selection criteria. Step 3: Parameter Estimation and Diagnostic Testing. This step includes estimating the model parameters and conducting diagnostic tests to assess the parameters’ significance, the model’s overall effectiveness, and whether the residuals form a white noise sequence. Step 4: Forecasting with the Established ARIMA Model. Once the model is validated, it forecasts future time series values based on historical data and estimated parameters. Each of these steps is critical to ensuring the robustness and accuracy of the ARIMA model in time series forecasting.

The BP neural network is a multilayer feedforward neural network trained using the error BP algorithm, and it is one of the most widely applied neural network models. The primary characteristics of the BP neural network are that signals propagate forward, while errors propagate backward. Specifically, the BP neural network process is divided into two stages. The first stage is the forward propagation of signals passing through the input and hidden layers and reaching the output layers. The second stage is the backward propagation of errors, adjusting the weights and biases from the output layer to the hidden layer and then to the input layer.

The mathematical relationship between the three layers of the neural network is expressed in Eq. (2): \(\:{x}_{i}\): Input variables to the neural network ; \(\:{\omega\:}_{ij}\): Weights between the input layer and hidden layer neurons; \(\:{a}_{j}\): Bias terms added to the weighted sum of inputs in the hidden layer; \(\:{F}_{j}\): Output of the hidden layer neurons after applying the activation function; \(\:{\omega\:}_{jk}\): Weights between the hidden layer and output layer neurons; \(\:{b}_{k}\): Bias terms added to the weighted sum of hidden layer outputs in the output layer; \(\:{O}_{k}\): Final output of the neural network; \(\:G\): Activation function used in the hidden layer.

If the expected output of the system is set to Tk, the error E of the system can be represented by the variance between the actual output value and the expected target value. The specific relationship is expressed by Eqs. (3) and (4) as follows:

By utilizing the principles of gradient descent, the relationship between the system’s weights and biases can be expressed, as shown in Eqs. (5) and (6):

Regularization can be incorporated to enhance the model’s representational capacity and adaptability while reducing the occurrence of overfitting to the training dataset. L1 and L2 regularization are commonly used regularization techniques to prevent Model overfitting and improve the Model’s generalization ability. They limit the complexity of the Model by adding additional penalty terms to the loss function. The loss function with added L1 regularization and L2 regularization is expressed in Eqs. (7) and (8):

The BP neural network model exhibits effective handling capabilities for nonlinear factors within the system, while the ARIMA model demonstrates robust capabilities in extracting time series patterns from accident data. These two models are combined for accident prediction to enhance the predictive accuracy.

Next, a residual optimization prediction combination method is employed to construct a composite prediction model for traffic accidents. The linear component of traffic accidents is predicted using the ARIMA model, and the residual data of traffic accidents are extracted. Subsequently, a BP neural network is constructed to fit and predict the nonlinear factors within traffic accidents. The final prediction results are obtained through the residual optimization combination prediction model.

Consider a set of time series data yt as being composed of a linear autocorrelation structure Lt and a nonlinear structure Nt. Their relationship is expressed as in Eq. (9):

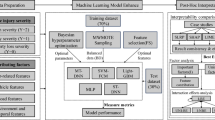

The ARIMA-BP prediction model involves three steps:

Step 1: The initial linear component prediction using ARIMA. Let yt be the original time series data. The ARIMA prediction result, denoted as \(\:{{L}_{t}}^{{\prime\:}}\), captures the primary linear trends and seasonal patterns. The residual et between the original sequence and ARIMA prediction is calculated as shown in Eq. (10):

The residual sequence {et} encapsulates the nonlinear components and complex patterns that the linear ARIMA model cannot adequately capture. This nonlinear relationship can be expressed through a functional mapping f with random error term \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{t}\), as shown in Eq. (11):

Step 2: Nonlinear residual pattern learning through BP neural network. Rather than using direct model combination, we employ a specialized BP neural network architecture to learn the complex nonlinear patterns in the residuals. The BP network incorporates domain-specific knowledge through the integration of the 13 identified traffic indicators. The network’s prediction \(\:{{N}_{t}}^{{\prime\:}}\) is optimized through:

where:

\(\:{x}_{t}\)represents the vector of traffic-specific indicators

\(\:\sigma\:\) denotes the activation function

\(\:{W}_{h}\)and \(\:{b}_{h}\) are the weight matrix and bias vector respectively

Step 3: Dynamic integration through multi-target optimization. The final prediction is obtained through a specialized integration framework given by Eq. (13):

where \(\:{{y}_{t}}^{{\prime\:}}\) is the final prediction result of the combined ARIMA-BP model.

This integration is further enhanced by a comprehensive multi-target optimization framework that simultaneously considers all four accident metrics:

where:

\(\:{\gamma\:}_{i}\) represents the importance weights for each accident metric

\(\:{y}_{i}\) corresponds to the actual values for accidents, fatalities, injuries, and property damage

The squared error term ensures robust optimization across all targets.

This methodological framework represents a significant advancement in hybrid modeling approaches for traffic accident prediction. The ARIMA component systematically captures linear temporal patterns and seasonal variations in the accident data, while the BP neural network specializes in learning complex nonlinear relationships through its residual optimization process. The integration of these complementary approaches through our multi-target optimization framework enables more comprehensive modeling of accident patterns than traditional single-model approaches. By simultaneously optimizing for all four accident metrics (accidents, fatalities, injuries, and property damage), the model maintains the intrinsic relationships between these variables while minimizing prediction errors across all targets. Figure 2 provides a detailed illustration of this sequential integration process, demonstrating the systematic flow from initial ARIMA prediction through BP-based residual optimization to final ensemble prediction. This architecture not only leverages the individual strengths of both ARIMA and BP models but also introduces additional synergistic benefits through its specialized integration framework and domain-specific optimizations.

Data sources and collection

The data originate from annual reports published on the National Bureau of Statistics website, as well as annual statistical data compiled from various indicators52. The historical statistical data for traffic accidents, fatalities, injuries, and property damage in China from 1990 to 2020 were compiled. The statistical analysis and visualization of traffic accident data in the transportation sector were conducted. Figure 3 illustrates the trends in the number of traffic accidents, fatalities and injuries, and property damage in China from 1990 to 2020. Starting in 1990, the numbers of four indicators continued to rise, reaching a peak in the early 2000s, followed by a sustained decline. After 2015, these four indicators exhibited a trend of continuous fluctuations, showing a relatively consistent pattern in their quantitative relationships.

Traffic accident Indicator selection

In this study, indicator collection and selection were carried out by considering both the gray relational analysis and the research relevance. The prediction target of this study is the macroscopic loss situation in transportation industry accidents. Therefore, among the numerous indicators related to the transportation industry, the primary selected indicators include the population, economy, roads, vehicles, drivers, and industry employment. On the other hand, the gray relational degree method was employed to calculate the correlation between each indicator and the occurrence of traffic accidents. The indicators were ranked based on the relational degree values. The relational degree values ranged from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating a stronger correlation with the parent sequence (accident occurrence), implying a higher level of correlation. Generally, a gray relational degree greater than 0.6 is considered highly correlated53, and this criterion was used for indicator selection.

Thirteen influencing factors related to traffic accidents were selected, including the national total income, gross domestic product (GDP), residents’ Engel coefficient, labor force, year-end total population, and road mileage, as well as the quantity of road-operated vehicles, the number of private cars, the number of civilian cars, the volume of road freight, the volume of road passengers, the number of employees in the road transportation industry, and the number of motor vehicle drivers. From Table 1, it can be observed that among the 13 selected indicators, the labor force (in tens of thousands) has the highest correlation, with a relational degree of 0.838, followed by the year-end total population (in tens of thousands), with a relational degree of 0.83, and residents’ Engel coefficient, with a relational degree of 0.802. The relational degree values for the other influencing factors are all greater than 0.6. The data preprocessing method used in the study is the Min Max normalization method, which performs dimensionality reduction on the data to ensure the rigor of data processing.

Model predictions

ARIMA model prediction

The ARIMA model was established to predict the future occurrence of traffic accidents, fatalities, injuries, and property damage for the next five periods. Figure 4 illustrates the autocorrelation function (ACF) of the residuals of the ARIMA model, including coefficients with upper and lower confidence limits. The horizontal axis represents the lag number, and the vertical axis represents the autocorrelation coefficients. This model requires that the residuals of the time series model be a white noise sequence. As shown in Fig. 4, all correlation coefficients are within the dashed lines, indicating that the residuals of the AR model are a white noise sequence. Figure 5(a) displays the fitted values of traffic accidents and the predicted values for the next five periods. It can be observed from the historical statistical values that the number of traffic accidents exhibits strong volatility and nonstationarity. The scatter plot of the predicted values indicates a growth trend in the number of accidents during the forecast period, with a relatively low growth rate. The ARIMA model’s goodness of fit (R²) regarding the number of accidents is 0.937, demonstrating excellent model performance. Table 2 presents the goodness of fit for various indicators, with goodness of fit values of 0.909, 0.904, and 0.857 for the death toll, injury count, and property damage, respectively, indicating good model fitting for these parameters.

The ARIMA model was then applied to predict the number of fatalities, injuries, and property damage. The model was trained on historical time series data from 1990 to 2015, the model fit was analyzed for the accident indicators, and predictions were made for the subsequent five periods. The fitted and predicted results are shown in Figs. 5(b), (c), and (d). These figures demonstrate that the model fits the historical accident data well, accurately capturing peaks and extreme values. The predicted results show a noticeable trend in accidents, fatalities, injuries, and property damage for the next five periods. Regarding prediction accuracy, the average annual prediction errors for the four indicators were 6.33%, 7.16%, 8.78%, and 9.40%, respectively, with the ARIMA model exhibiting the highest accuracy in terms of predicting the number of accidents and the lowest accuracy in predicting the property damage. In conclusion, the ARIMA model demonstrates good data fitting but requires improved prediction accuracy for the analyzed traffic accident indicators.

BP neural network prediction

The BP neural network model for prediction was implemented using MATLAB software version 2020b. Predictions for the number of traffic accidents, fatalities, injuries, and property damage for the next five periods were made by establishing a neural network model. A 3-layer neural network structure was employed, with 13 neurons in the input layer and 4 neurons in the output layer. The number of nodes in the hidden layer was determined through trial and error. Different numbers of nodes were selected, the training error was calculated, and the model parameters were adjusted to minimize the training error. The final number of nodes in the hidden layer was determined to be 8, providing a fitting R coefficient of close to 1, indicating good model performance. Figure 6 illustrates the neural network structure for traffic accident prediction, including each accident indicator’s input layer, hidden layer, output layer, and variables. The data were split into training (70%), validation (15%), and testing (15%) sets. Thirteen selected variables from Sect. “Traffic accident indicator selection” were used as input indicators for the neural network. The chosen traffic accident analysis indicators included economic factors (national income, gross domestic product, and Engel coefficient), macro population factors (labor force, year-end total population, and number of motor vehicle drivers), and passenger and freight volume factors (road mileage, number of road operating vehicles, number of private cars, number of civilian cars, road freight volume, road passenger volume, and number of employees in the road transport industry). The output indicators comprised the number of accidents, fatalities, injuries, and property damage. The neural network model was trained using traffic accident data, and the output error histogram (Fig. 7) and the neural network goodness of fit curve (Fig. 8) indicated low errors on both the training and testing sets, demonstrating good training performance.

The BP neural network studied the relationships and nonlinear information in the accident data, confirming that economic, human, and road factors influence traffic accidents. The traffic accident indicators, to some extent, affect the trend changes in traffic accident losses. Figures 9 and 10 depict the mean square error curve and the model prediction results. It is evident that accident losses, the numbers of accidents, fatalities, and injuries, and property damage all show a continuous upward trend from 2016 to 2020, reaching 257,432, 82,099, 263,728, and 152,484, respectively, at the end of the prediction period. The BP model exhibits the highest accuracy in predicting the number of accidents, while the predicted values for fatalities deviate significantly from the actual values. Using Eq. (13), the annual average errors of the BP neural network prediction model were 6.42%, 20.32%, 10.10%, and 9.34% for the number of accidents, fatalities, injuries, and property damage, respectively. Compared to the ARIMA model, the BP model predictions better reflect the fluctuation trends in the actual accident data. There is still considerable room for improvement in the prediction accuracy of the BP model.

ARIMA-BP model prediction results

According to the construction method of the ARIMA-BP model based on the residual optimization approach in Sect. “Construction of the combined ARIMA-BP model”, an ARIMA-BP model was established using the controlled variable method. The input indicators of the model were kept consistent with those of the BP neural network. This model predicts the number of traffic accidents, fatalities, injuries, and property damage for 2016–2020. The model predictions were then compared with the actual values of accident losses, and the prediction errors of the ARIMA-BP model were calculated. Furthermore, the predicted results were compared with the predictions of individual models to analyze and compare the forecasting effectiveness of different models. The annual average error rate \(\:\overline{\text{T}}\) was employed as the measure of accuracy for different model predictions, as indicated in Eq. (13):

The ARIMA-BP model was used to forecast the four indicators of traffic accident losses mentioned above. Table 3 presents the predicted values of traffic accidents, fatalities, injuries, and property damage for 2016–2020. The results indicate that during the forecast period from 2016 to 2020, the average annual error rates of the ARIMA-BP model for the four indicators—crash frequency (number of accidents) and crash severity (number of fatalities, number of injuries, and property damage)—are 4.16%, 3.67%, 7.45%, and 5.94%, respectively, with an overall average prediction error rate of 5.31%. Further comparative analysis of the forecasting performance of different models is presented in Fig. 11, depicting the trend of the predicted results from 2016 to 2020. The chart illustrates the future development of traffic accident losses. From Figs. 11 (a), (b), (c), and (d), it is evident that the ARIMA-BP model exhibited good forecasting accuracy for the number of traffic accidents, with predicted values for 2017 and 2020 closely matching the actual values. The ARIMA-BP model yielded smaller prediction residuals for fatalities, particularly in 2016 and 2018, compared to those of the two individual models. The model prediction error for the number of injuries was lower than that of the ARIMA and BP models, demonstrating the higher prediction accuracy for the combined model. In predicting property damage, the ARIMA-BP model also achieved the highest accuracy, and the curve reflects the true fluctuations in property damage during the forecast period. The analysis of the results indicates that while the BP model is accurate in some years, it lacks stability, resulting in a relatively low average prediction accuracy. With an overall linear trend, the ARIMA model exhibits improved accuracy compared to that of the BP model but fails to capture the variations in traffic accident losses. The combined ARIMA-BP model provides more accurate predictions for traffic accident losses than those of the individual models. The model trends align well with the actual data series, better reflecting the true trajectory of the accident data.

Comparison of the prediction effects of different models in traffic accidents from 2016–2020. The predicted results of the ARIMA-BP model align most closely with the actual outcomes, while the ARIMA model exhibits a noticeable linear trend in its predictions, and the BP model’s forecasted results display higher volatility.

Discussion

This section discusses how to incorporate the nonlinear information of traffic accident data into predictions while ensuring prediction stability using the ARIMA-BP model accurately and effectively. The ARIMA model exhibits good stability as a time series model due to the constraints imposed by the historical data series characteristics, model parameters, and seasonal trends. The residual autocorrelation plot and model prediction results of the ARIMA model show that the residuals form a white noise sequence with low correlation coefficients, meeting the requirements for prediction. The ARIMA model relies entirely on fitting and calculating historical accident data, displaying a strong linear pattern in the prediction results. In the prediction process, it is essential to consider the impact of various complex factors on traffic safety accidents, such as road conditions, traffic flow, weather, and other factors. Since the complex relationships affecting accident occurrence encompass numerous nonlinear data information, linear models cannot adequately capture these relationships, underscoring the importance of effectively extracting nonlinear information from the data.

The limitation of the ARIMA model lies in its failure to consider the influence of other factors on traffic accidents. Thus, this model lacks mechanistic reasoning. To address the lack of mechanistic reasoning in predictions and enhance the interpretability of the results, the nonlinear modeling capability of the BP model is employed to accommodate various complex data relationships, allowing for a more flexible capture of nonlinear patterns in time series data built upon the ARIMA model. Through optimization methods such as backpropagation and gradient descent, neural networks can learn the nonlinear relationships in the data. The multilayer structure of neural networks (input layer, hidden layer, layer, output layer) allows for representing complex nonlinear functions by combining multiple nonlinear transformations. Thus, this approach adequately considers the nonlinear information in traffic accidents, improving the prediction efficiency. An analysis of the results from the BP model reveals that, compared to the ARIMA model, the predictions are no longer a simple linear relationship. As the prediction introduces indicators related to traffic accidents and fits the model, the trend of predicted values aligns more closely with real accident data, better reflecting the changing trajectory of accident losses compared to the ARIMA model. The prediction accuracy of the BP neural network model fluctuates significantly, with a maximum annual average error rate of 20.32%. The prediction errors are generally higher than those of the ARIMA model, indicating ample room for improved accuracy.

To ensure the accuracy of traffic accident predictions and consider the nonlinear information in the data, this study introduces traffic accident indicators and utilizes the ARIMA-BP model for combined forecasting. By combining linear and nonlinear methods, the real data distribution better fits, providing higher prediction accuracy. The accuracy of each model is calculated for a better comparative analysis of the forecasting effects. The precision comparison among the ARIMA, BP, and ARIMA-BP models is illustrated in Fig. 12, where the selected ARIMA-BP model in the study exhibits annual average error rates of 4.16%, 3.67%, 7.45%, and 5.94%. In comparison, the ARIMA model achieves annual average error rates of 6.33%, 7.16%, 8.78%, and 9.40%, while the BP neural network model yields error rates of 6.42%, 20.32%, 10.10%, and 9.34%. The ARIMA-BP model demonstrates the most negligible minor prediction errors, the highest accuracy, and optimal forecasting performance.

The ARIMA-BP model selected in this study demonstrates superior adaptability to different types of traffic accident data and prediction challenges compared to single models. While standalone models, such as the BP neural network, may be prone to overfitting due to their complex structures, the ARIMA-BP model mitigates this issue by integrating multiple model frameworks. This integration reduces overfitting risk and enhances robustness to outliers and noisy data, as the combined strengths of ARIMA and BP provide a balanced approach to addressing data irregularities.

Furthermore, the ARIMA-BP model’s hybrid nature allows for greater generalizability across diverse problem domains. Unlike single models, which may be overly sensitive to specific data patterns, the ARIMA-BP model achieves more reliable predictions by effectively capturing both linear and nonlinear relationships in traffic accident data. This makes it particularly suitable for dynamic and multifaceted prediction problems like traffic safety. In addition, by comparing with similar prediction studies, it can be found that the ARIMA-BP model used in the research has advantages compared to other commonly used prediction methods. Here’s the revised paragraph:

For example, in comparison with the LSTM model, it can be found that using the ARIMA-BP model for prediction is more advantageous than using the LSTM-GBRT model in the context of the same Chinese traffic accident data54. This is manifested in more comprehensive prediction indicators, predictions of future trends in accident data, and smaller error rates in specific years. Both research predicted the number of traffic accident deaths in 2016, which is the overlapping part of the prediction periods in the two studies. The prediction accuracy can be compared using the results of this year. By calculating the predicted percentage error of the number of deaths in traffic accidents in China in 2016, it can be seen that the error of the ARIMA-BP model is -1.31%, while the error of the LSTM-GBRT model is 8.42%.

To further validate these findings, we implemented our own LSTM model using the same dataset and prediction period as our ARIMA-BP model. A comprehensive comparison was conducted across all four prediction targets (accidents, fatalities, injuries, and property damage) for the years 2016–2020. Table 4 present the detailed comparison results. The ARIMA-BP model demonstrated consistently lower annual average error rates across all metrics and years, with the most significant improvement observed in Injuries predictions (5.21% reduction in error rate). To validate the performance differences between ARIMA-BP and LSTM models, we conducted Wilcoxon signed-rank tests on the annual error rates across all four prediction targets (2016–2020). The tests confirmed that ARIMA-BP model achieved significantly lower error rates for accidents (W = 0, p < 0.05), fatalities (W = 0, p < 0.05), injuries (W = 0, p < 0.05) and property damage (W = 0, p < 0.05).These results provide strong empirical evidence for the superior predictive capabilities of our ARIMA-BP model compared to LSTM approaches in traffic accident prediction tasks.

In terms of predicting inflection points in accident data, the ARIMA-BP model has the ability to predict inflection points, and the fluctuation trend of the predicted results is more in line with the actual data, while the LSTM model does not have the ability to predict inflection points. The accurate forecasting capabilities of the ARIMA-BP model provide significant data-driven decision support for traffic management departments. By offering precise predictions of accident patterns, the model aids in developing more effective traffic management and safety strategies. For example, management can use these forecasts to allocate resources more efficiently—focusing on high-risk areas and critical periods to minimize the likelihood of accidents.

In summary, the ARIMA-BP model is crucial in identifying key risk factors contributing to traffic accidents. Through analyzing these predictive insights, traffic authorities can implement targeted preventive measures to mitigate these risks. For instance, if certain weather conditions or congestion levels are shown to significantly increase accident risks, authorities can proactively address these factors through tailored interventions such as public advisories, traffic rerouting, or enhanced safety measures. By adopting such data-driven preventive strategies, the ARIMA-BP model not only helps reduce accident rates but also minimizes casualties and property damage.

Conclusion

In this study, the causal relationships underlying traffic accidents were systematically analyzed, and a comprehensive risk assessment was conducted by examining factors related to people, vehicles, and road conditions. Relevant accident indicators were selected to construct the ARIMA time series, BP, and ARIMA-BP models. Three different prediction methods were applied to forecast traffic accident losses. The accuracy and effectiveness of the established single and ARIMA-BP prediction models were compared and analyzed by calculating the error rates in predicting traffic accident losses. This study effectively enhances the precision of predicting traffic accident losses, offering valuable insights for future studies on traffic accident prediction. Integrating the ARIMA and BP models allows for better handling of linear trends and nonlinear patterns within this context. Moreover, we introduced a residual optimization technique that improves model performance specifically for the complexities of traffic data, which has not been extensively explored in previous studies. The conclusions are summarized as follows.

1) A systematic risk analysis of traffic accidents was conducted at the individual, vehicle, and road levels, resulting in a causal flowchart depicting the evolutionary relationship of traffic accident risks. Multiple factors influence road traffic accidents, including vehicle, pedestrian, and environmental risks. Due to the complexity of the mechanisms involved in traffic accidents, ARIMA and BP neural network models were selected to predict accident losses. These models were combined to leverage their respective advantages and address the poor predictive performance associated with individual models.

2) ARIMA and BP neural network models were constructed to predict traffic accident losses in the same forecast period, and four types of traffic accident losses were predicted. The former uses time series data directly for prediction, while the latter considers factors influencing traffic accidents in predictions, introducing traffic accident indicators. A comparison of the forecasting effects of the ARIMA models and BP neural network models was conducted by calculating the error rates of different prediction models. The annual average error rates of the former for the four accident indicators were 6.33%, 7.16%, 8.78%, and 9.40%, while the latter had error rates of 6.42%, 20.32%, 10.10%, and 9.34%. The ARIMA model exhibited higher prediction accuracy for accidents, fatalities, and injuries. This result could be attributed to the lower volatility of traffic accident data around the forecast period, where the differencing process applied by the ARIMA model enhanced the data stationarity, allowing the model’s advantage in analyzing time series data relationships to be more pronounced.

3) Employing the residual optimization method to construct the ARIMA-BP model for predicting traffic accident losses resulted in annual average error rates of 4.16%, 3.67%, 7.45%, and 5.94%. The ARIMA-BP model’s average annual error rate for the four indicators was 5.31%, compared to 7.92% for the ARIMA model and 11.55% for the BP model. The prediction error rates of the ARIMA-BP model were 2.61% and 6.24% lower than those of the ARIMA and BP neural network models, respectively. The ARIMA-BP model exhibited the smallest prediction errors, the highest accuracy, and the best forecasting performance. The ARIMA model’s predictions were approximately linear and unable to reflect the changing trend in traffic accident data, while the BP model’s predictions showed some volatility. The ARIMA-BP model’s predictions demonstrated the best trend conformity, capturing the data trend closest to the real data.

Due to the limited availability of publicly accessible data on traffic accidents, the study used annual data without forecasting from a monthly or quarterly perspective. Future research should continue to improve the forecasting effectiveness across different data dimensions, further validating the accuracy of the ARIMA-BP model.

Data availability

Data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS). (China statistical yearbook 1990-2020. China Statistics: Press 1990-2020; Beijing.)

References

Marcillo, P., Caraguay, V., Hernández-Álvarez, M. & Á. L., & A systematic literature review of Learning-Based traffic accident prediction models based on heterogeneous sources. Appl. Sci. 12 (9), 4529 (2022).

Shaik, M. E., Islam, M. M. & Hossain, Q. S. A review on neural network techniques for the prediction of road traffic accident severity. Asian Transp. Stud. 7, 100040 (2021).

Lim, B. & Zohren, S. Time-series forecasting with deep learning: a survey. Philosophical Trans. Royal Soc. A. 379 (2194), 20200209 (2021).

Sarstedt, M., Mooi, E., Sarstedt, M. & Mooi, E. Regression analysis. A concise guide to market research: The process, data, and methods using IBM SPSS Statistics, 209–256. (2019).

Comert, G., Begashaw, N. & Huynh, N. Improved grey system models for predicting traffic parameters. Expert Syst. Appl. 177, 114972 (2021).

Yang, Y., Wang, K., Yuan, Z. & Liu, D. Predicting freeway traffic crash severity using XGBoost-Bayesian network model with consideration of features interaction. Journal of advanced transportation, 2022. (2022).

Zhou, X., Lu, P., Zheng, Z., Tolliver, D. & Keramati, A. Accident prediction accuracy assessment for highway-rail grade crossings using random forest algorithm compared with decision tree. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 200, 106931 (2020).

Singh, G., Pal, M., Yadav, Y. & Singla, T. Deep neural network-based predictive modeling of road accidents. Neural Comput. Appl. 32, 12417–12426 (2020).

Gutierrez-Osorio, C. & Pedraza, C. Modern data sources and techniques for analysis and forecast of road accidents: A review. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (English edition). 7 (4), 432–446 (2020).

Yassin, S. S. & Pooja Road accident prediction and model interpretation using a hybrid K-means and random forest algorithm approach. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 1–13 (2020).

Miller, J. W. ARIMA time series models for full truckload transportation prices. Forecasting 1 (1), 121–134 (2018).

Van Der Voort, M., Dougherty, M. & Watson, S. Combining Kohonen maps with ARIMA time series models to forecast traffic flow. Transp. Res. Part. C: Emerg. Technol. 4 (5), 307–318 (1996).

Zhang, R. Xie Fei,Shi Jianjun,Zhao Jing,Yang Jiquan Ling Xu.(2022).Spatial-Temporal Semantic Neural Network for Time Series Forecasting.Journal of Physics: Conference Series(1).

Abojaradeh, M. Development of traffic accident prediction models to improve traffic safety and to reduce traffic accident severity and rate in Jordan. J. Biol. Agric. Healthc., 5(2), 42–54 (2015).

Xu, Z., Saleh, J. H. & Subagia, R. Machine learning for helicopter accident analysis using supervised classification: inference, prediction, and implications. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 204, 107210 (2020).

Ye Fei-Fei,Yang Long-Hao,Wang Ying-Ming Lu Haitian. A data-driven rule-based system for China’s traffic accident prediction by considering the improvement of safety efficiency (Computers Industrial Engineering, 2023).

Wu, M. et al. A multi-attention dynamic graph Convolution network with cost‐sensitive learning approach to road‐level and minute‐level traffic accident prediction. IET Intel. Transport Syst. 17 (2), 270–284 (2023).

Gorzelanczyk, P. Application of neural networks to forecast the number of road accidents in provinces in Poland. Heliyon 9(1), e12767 (2023).

Zhan Weiyun,Li Haitao,Wu Xuefeng,Zhang Jingyue,Liu Chenxi Zhang Dongming. Research on neural network prediction method for upgrading scale of natural gas reserves.Frontiers in Earth Science. (2023).

Yang, Z., Zhang, W. & Feng, J. Predicting multiple types of traffic accident severity with explanations: A multi-task deep learning framework. Saf. Sci. 146, 105522 (2022).

Zargari, S. A., Khorshidi, N. A., Mirzahossein, H., Shakoori, S. & Jin, X. Travel time reliability prediction by genetic algorithm and machine learning models. In Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Transport (pp. 1–10). Thomas Telford Ltd. (2022), December.

Jiang, W. & Luo, J. Graph neural network for traffic forecasting: A survey. Expert Syst. Appl. 207, 117921 (2022).

Tian, Z. & Zhang, S. Deep learning method for traffic accident prediction security. Soft. Comput. 26 (11), 5363–5375 (2022).

Sawalha, Z. & Sayed, T. Transferability of accident prediction models. Saf. Sci. 44 (3), 209–219 (2006).

Lin, L., Wang, Q. & Sadek, A. W. A novel variable selection method based on frequent pattern tree for real-time traffic accident risk prediction. Transp. Res. Part. C: Emerg. Technol. 55, 444–459 (2015).

Yasin Çodur, M. & Tortum, A. An artificial neural network model for highway accident prediction: a case study of erzurum, Turkey. PROMET-Traffic&Transportation 27 (3), 217–225 (2015).

Yannis, G., Dragomanovits, A., Laiou, A., La Torre, F., Domenichini, L., Richter,T., … Karathodorou, N. (2017, October). Road traffic accident prediction modelling:a literature review. In Proceedings of the institution of civil engineers-transport(Vol. 170, No. 5, pp. 245–254). Thomas Telford Ltd.

Lin, D. J., Chen, M. Y., Chiang, H. S. & Sharma, P. K. Intelligent traffic accident prediction model for internet of vehicles with deep learning approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 23 (3), 2340–2349 (2021).

Ma, Z., Mei, G. & Cuomo, S. An analytic framework using deep learning for prediction of traffic accident injury severity based on contributing factors. Accid. Anal. Prev. 160, 106322 (2021).

Hu, Y. Traffic Fatality Rate Prediction Based on Deep Neural Network and Bayesian Neural Network (Doctoral dissertation, Northern Illinois University). (2021).

Guo, Q., Guo, B., Wang, Y., Tian, S. & Chen, Y. A Combined Prediction Model Composed of the GM (1, 1) Model and the BP Neural Network for Major Road Traffic Accidents in China. Mathematical Problems in Engineering, 2022. (2022).

Zheng, J. & Wu, X. Prediction of road traffic accidents using a combined model based on IOWGA operator. Periodica Polytech. Transp. Eng. 43 (3), 146–153 (2015).

Bates, J. M. & Granger, C. W. The combination of forecasts. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 20 (4), 451–468 (1969).

Zhang, G. P. Time series forecasting using a hybrid ARIMA and neural network model. Neurocomputing 50, 159–175 (2003).

Zheng, X. & Liu, M. An overview of accident forecasting methodologies. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 22 (4), 484–491 (2009).

Yannis, G., Dragomanovits, A., Laiou, A., Richter, T., Ruhl, S., La Torre, F., … Li, H. Use of accident prediction models in road safety management–an international inquiry. Trans. Res. Proc. 14, 4257–4266 (2016).

Zheng, Y. Measurement model of social and economic loss of traffic accident based on particle swarm optimization. Adv. Transp. Stud. 1, 27–36 (2022).

Dey, B., Roy, B., Datta, S. & Ustun, T. S. Forecasting ethanol demand in India to Meet future blending targets: A comparison of ARIMA and various regression models. Energy Rep. 9, 411–418 (2023).

Han, L. N., Ma, X. Z., Tan, J. D., Li, J. H. & Dong, Y. Q. Balancing material supply-demand with ARIMA and neural networks. Int. J. Simul. Model. 22(4), 712–722 (2023).

Lwaho, J. & Ilembo, B. Unfolding the potential of the ARIMA model in forecasting maize production in Tanzania. Bus. Analyst J. 44 (2), 128–139 (2023).

Mati, S. et al. Incorporating Russo-Ukrainian war in Brent crude oil price forecasting: A comparative analysis of ARIMA, TARMA and ENNReg models. Heliyon 9(11), e21439 (2023).

Wen, T., Liu, Y., Bai, Y. & Liu, H. he& Modeling and forecasting CO2 emissions in China and its regions using a novel ARIMA-LSTM model. Heliyon, 9(11). (2023).

Zhou, Z. H. Machine Learning (Springer Nature, 2021).

Siami-Namini, S., Tavakoli, N. & Namin, A. S. A comparison of ARIMA and LSTM in forecasting time series. In 2018 17th IEEE. (2018), December.

Mulkey, D. C., Fedo, M. A. & Loresto, F. L. Jr Analyzing a multifactorial fall prevention program using ARIMA models. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 38 (2), 177–184 (2023).

Tarmanini, C., Sarma, N., Gezegin, C. & Ozgonenel, O. Short term load forecasting based on ARIMA and ANN approaches. Energy Rep. 9, 550–557 (2023).

Lu, S. Research on GDP forecast analysis combining BP neural network and ARIMA model. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2021(1), 1026978 (2021).

Wang, X. Research on the prediction of per capita coal consumption based on the ARIMA–BP combined model. Energy Rep. 8, 285–294 (2022).

Hou, L. & Chen, H. The prediction of Medium-and Long-Term trends in urban carbon emissions based on an ARIMA-BPNN combination model. Energies 17 (8), 1856 (2024).

Sayed, H. A., William, A. & Said, A. M. Smart electricity meter load prediction in Dubai using MLR, ANN, RF, and ARIMA. Electronics 12 (2), 389 (2023).

Khan, S. & Alghulaiakh, H. ARIMA model for accurate time series stocks forecasting. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 11(7). (2020).

National Bureau of Statistics of China (NBS). China Statistical Yearbook 1990–2020. China Statistics:1990–2020; Beijing (2021).

Wagner, I. I. I. & W. E Using IBM® SPSS® statistics for research methods and social science statistics (Sage, 2019).

Zhang, Z., Yang, W. & Wushour, S. Traffic accident prediction based on LSTM-GBRT model. J. Control Sci. Eng. 2020 (1), 4206919 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support by the National Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52004139) and the National Key R&D Program of China (No.2017YFC0804901), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. FRF-TP-22-120A1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jian Liu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review &editing.Zhuqing Zhang: Writing - review &editing, Methodology, Software, Data Curation, Formal analysisBin Lyu: Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review &editing, Formal’ analysis, Investigation.Rui Feng: Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Funding acquisition.Ye He: Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review &editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, J., Zhang, Z., Lyu, B. et al. A hybrid ARIMA-BP approach for superior accuracy in predicting traffic accident losses. Sci Rep 15, 24328 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09888-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09888-x